Abstract

To systematically synthesize published literature on somatoform complaints as psychological factors in vertigo/dizziness to determine the characteristics of comorbidities, relationships and causality. Following PRISMA guidelines, systematic searches of PubMed, WOS, and Cochrane Library databases and manual follow-up reference searches were performed for articles published in English up to 2021. All original research studies and retrospective or prospective studies focusing on the relationship between vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization were systematically retrieved. Studies that did not include data on the association between somatoform complaints/somatization and vertigo/dizziness were excluded, as were reviews, comments, case reports, editorials, letters, and practice guidelines. Extracted data included research type, number of participants, assessment tools for vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization, statistical methods, and the main results. The quality of included studies was evaluated. Records identified through database searching n = 1238. After removing duplicates and unrelated articles based on abstract and title search, 155 articles recorded as relevant. Except for the 5 articles, title and abstract of all records screened and 88 of them excluded. Critically evaluating those full texts, 28 studies included. The present study highlights the relationship between the vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization. It is determined that somatoform complaints of the individuals suffering from vertigo/dizziness is highly prevelant and some other factor such as personality characteristics or accompanying psychopathology have affect on the prevelance. The main results of all reviewed studies emphasize the requirement for assessment and intervention of vertigo/dizziness, in collaboration with the department of psychiatry. PROSPERO REGISTRATION: PROSPERO: CRD42020222273.

Keywords: Dizziness, Vertigo, Somatoform complaints, Systematic review

Introduction

Vertigo is a state of illusion in which the person feels that his surroundings and/or himself revolves and mostly accompanied by perspiration and nausea [1, 2]. The other definitions that are expressed by patients suffering from vertigo are feeling of revolving in space, tipping over, swaying, being shoved or falling. As a symptom, vertigo may occur with or without the presence of an organic illness. Furthermore, it is very frequent accompanying psychogenic complaints like anxiety and depression in patients with vertigo complaints, although different incidence/ prevelance rates indicated in the literature, [3–5]. Vertigo has various negative affects on individuals such as functional limitations and inability [1] and is among the most common reasons to consult a physician [6].

As a general term somatoform complaints/somatization are physical complaints to the presence of a psychosocial stress and the behaviour to seek medical help for resolving this situation. For many years, chronic physical complaints/ symptoms without any organic cause has been labelled with different diagnoses such as psychiatric, psychogenic, psychosomatic, somatoform or somatization under different classifications. Somatoform/Somatization Disorders is the term which is preferred in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition [7] and World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases-10th Revision (ICD-10) [8] and includes: somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, Conversion disorder, Body dysmorphic disorder and undifferentiated somatoform disorder [9]. On the other hand, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [10] replaces somatoform disorders with somatic symptom and related disorders and makes significant changes to the criteria to eliminate overlap across the somatoform disorders and clarify their boundaries. Here, somatic symptom disorder (SSD) is characterized by somatic symptoms that are either very distressing or result in significant disruption of functioning, as well as excessive and disproportionate thoughts, feelings and behaviors regarding those symptoms and includes: somatic symptom disorder, illness anxiety disorder, conversion disorder, pain disorder, unspecified somatic symptoms and related disorder [9].

Although, in literature, it has been pointed that simultaneous biopsychosocial approach to non-specific, functional, and somatoform bodily complaints helps the early diagnosis [11] and in some clinics increased attention has been given to some psychological conditions in relation to vertigo, relatively little is known about associated somatoform complaints/somatization. Moreover, vertigo that results from somatoform complaints/somatization does not take place among the differential diagnosis criteria and because of this, the diagnosis for these patients takes more time to cause a delay [12]. In this regard, we hypothesized that the direction and extention of the relationship between vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints can be revealed. Therefroe; the objective of this review was to systematically summarize the published literature on somatoform complaints/ somatization as psychological factors in vertigo/dizziness (and related terms) to figure out characteristics of the comorbidity, relationship and causality.

Methods

In this review the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-PRISMA [13] was followed. The corresponding review protocol is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews before the study starts (PROSPERO: CRD42020222273).

The electronic databases of Web of Science (Core collection), PubMed, and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched and manual follow-up reference searches were performed for articles published in English up to February 2021 in order to retrieve potential studies. A search string for WOS was developed and consisted of keywords such as “vertigo”, “dizziness”, “unsteadiness”, “lightheadedness” and ”somatorm” and “somatization”. In order to reach at all words related to somatorm and somatization, the abbreviation “somat*” is used as suggested by search engines. All key words were consisted of Medical Subject Headings terms and free-text words.The search string was adjusted for use in the other electronic databases. All search strings were verified by a experienced librarian. A sample of the search strings is as follow:

(AB = ((vertigo OR dizziness OR unsteadiness OR lightheadedness) AND somat*)) AND LANGUAGE: (English).

AND DOCUMENT TYPES: (Article).

Indexes = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI Timespan = All years

The search was performed using English language and without date information. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the Supplementary Information. Duplicate studies were excluded.

Study Selection

All original research studies and retrospective/prospective studies focusing on the relationship between vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization were systematically retrieved. Experiments, observational studies, clinical studies and randomized controlled trials investigating the vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization together were all included. The studies examining the somatoform alone or with other psychological disorders in relation to vertigo/dizziness were considered relevant. Studies that did not include data regarding the association between somatoform complaints/somatization and vertigo/dizziness were excluded, as were reviews, comments, case reports, editorials, letters, and practice guidelines. Exclusion criteria were defined as; not including human subjects, not giving full details on the tools used to evaluate vertigo/dizziness and/or somatoform complaints/somatization.

The inclusion criteria in terms of the PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study Design) were Population: adults and older people with vertigo/dizziness and/or somatoform complaints/somatization. Intervention: psychotherapies or medical treatments (RCTs)/ psychotherapies (observational studies); Comparison: any control group (RCTs), (observational studies); Outcome measures: the relationship between vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints as causality or at least comorbidity; and Study Design: observational studies (case–control, cohort studies, retrospective studies) and RCTs.

The screening based on titles and abstracts were performed and then the full-text studies were carefully reviewed. In addition, the reference lists of the included studies were thoroughly searched by hand for possible additional studies. All steps conducted by two authors collaboratively and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

A dedicated Microsoft Excel form was prepared for grouping the studies. The following information for each eligible study were retrieved: study identification (first author, title, publication year); study characteristics (place –country/clinic- and design); research participants (number and age), tool used to collect information (for vertigo/dizziness and for somatoform complaints/somatisation), statistical methods and main findings.

Assessing methodological quality and risk of bias, the validated checklists Study Quality Assessment Tools of NIH checklists published by the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for quantitative study designs [14] were applied. The tool provides a framework for considering risk of bias foresees 3 possible judgments: low risk, some concerns, and high risk.

Results

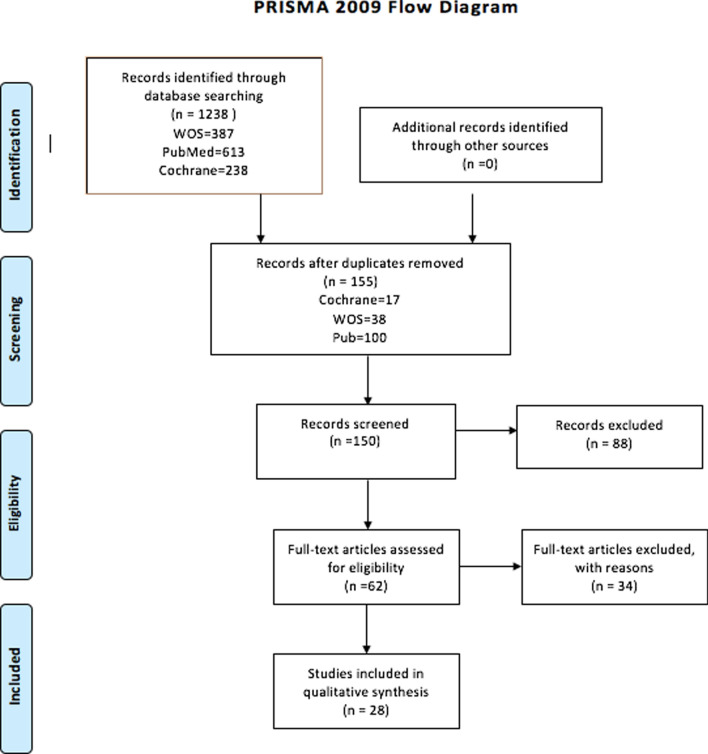

Records identified through database searching n = 1238. After removing duplicates and unrelated articles based on abstract and title search, 155 articles recorded as relevant. Except for the 5 articles, title and abstract of all records screened and 88 of them excluded. By this way, 62 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. Critically evaluating those full texts, 28 studies included in the review. See Fig. 1 for a flowchart.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram (Identification, Screening, Eligibity, Included)

The information for study identification (first author, publication year), country and clinic where the study was conducted, number and age of participants, the study design and statistical methods of the 28 included studies is presented in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterstics of the 28 included studies

| Ref. no | Authors, Date Clinic, Country |

N | Age Range (Mean) Year |

Research Design | Statistical Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 |

Persoons et al. [15] Belgium, Otolaryngology |

268 | 18–65 (48.2) | Observational/ Cross Sectional Study |

Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test The Levene’s test, ANOVA Cohen’s -value, Bonferroni correction |

| 16 |

Ardic et al. [16] Turkey, Vertigo Outpatient Clinic |

518 | NA (46.4) | Observational/ Cross Sectional Study | Student’s t, Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal Wallis, Pearson’s correlation tests |

| 17 |

Best,Best et al. [17] Germany, Neurology and Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy |

101 case 26 control |

22–73 (44.67) | Prospective Interdisciplinary Study | Student’s t test, ANOVA, MANCOVA, Post hoc tests (LSD), Pearson’s correlation tests |

| 18 |

Özdilek et al. [18] Turkey, in the Ear Nose Throat (ENT) and Neurology Outpatient Clinics |

60 case- 60 control |

Patient 24–81 (40.4 Healthy 18–71 (38.2) |

Single-center Prospective Case–control Study |

Descriptive statistics, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Chi-square tests, The Mann–Whitney U test, Spearman rank correlation |

| 19 |

Limburg et al.[19] Germany, Centre for Vertigo and Balance Disorders, Neurological Setting |

399 | NA (53.8) |

Descriptive statistics, ANOVA, Chi-square tests Cohen's Kappa |

|

| 20 |

Limburg et al. [20] Germany, German Centre for Vertigo and Balance Disorders |

239 | NA (57.8) | Longitidunal Study |

Descriptive statistics, ANOVA, Post-hoc tests, Chi-square tests, multivariable logistic regression |

| 21 |

Limburg et al. [21] Germany, German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders, Neurology, Psychology |

392 | Secondary Cross-sectional analysis of a Longitudinal Study | Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test, Chi-square tests, Cohen’s Kappa coefficient | |

| 22 |

Habs et al. [22] Germany, German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders |

356 | 18–81 (46) |

Database-driven Study |

Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) and equality of variances. and Mann–Whitney U test, Fisher’s exact test. Chi-square tests, Pearson’s correlation tests |

| 23 |

Yardley et al. [23] Neuro-otology Clinic |

127 | 18–80 (46.5) | ||

| 24 | Piker et al. [24], Vanderbilt, Balance Disorders Clinic | 63 | 27–82 (54) | ||

| 25 |

Lucy Yardley [25] …….., Otology neuro-otology |

101 |

For female 18–80 (45.2), For male (51.6) |

Longitudinal Study | factor analyses, Hierarchical multiple regressions |

| 26 |

Best et al. [26] ………, Departments of Neurology and Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy |

68 | (52) | Interdisciplinary Longitudinal Study | ANCOVA, Post hoc t-tests, multiple Pearson’s correlation tests, Chi-square tests |

| 27 |

Garcia et al. [27] nöroloji, psikiyatri, nöro-otol |

60 | 18–82 (53.3) | A Pilot Prospective Observational Study | Descriptive statistics |

| 28 | Godemann et al. [28], Psychiatry, Neuro-otology Clinics | 103 | (50) | NA |

Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlation tests, Partial correlation was calculated for the determination of apparent correlations. Stepwise linear regression analysis |

| 29 |

Kroenke et al. [29] USA, Walk-İn Clinic, Emergency Room, İnternal Medicine Clinic, or Neurology Clinic |

100 case- 25 control |

Patient (61.7), Control (66.4) | Prospective Observational Study |

ANOVA, Chi-square tests, logistic regression model |

| 30 |

Monzanı et al. [30] Italy, ENT Clinic and the Emergency Unit |

50 case- 50 control |

30–65 (43.59) | Case–Control Study |

Descriptive statistics, Wilcoxon test, |

| 31 | Eckhardt-Henn et al. [3] Germany, Neurology Outpatient Clinic | 202 | 19–64 | Observational Study |

Student’s t test, ANOVA, MANOVA, Post hoc tests (Scheffe` tests) the w2 test. there was no correction for multiple testing (alpha-inflation) |

| 32 |

Probst et al. [31] Germany, Centre for Vertigo and Balance Disorders |

111 | (53.55) | Longitidunal Study | Student’s t test, Chi-square tests, Pearson’s correlation tests, moderation and mediation analyses, bootstrapping (a resampling technique) confidence intervals (CI), |

| 33 |

Tschan et al. [32] Germany, Department for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy |

59 | (52) | Prospective Interdisciplinary Longitidunal Study | Student’s t test, LISREL, Chi-Square-test, Fisher’s exact test. Pearson’s correlation tests, Cohen’s d |

| 34 |

Tschan et al. [33] Germany, Clinic of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Neurology Department |

92 | (41.8) | Interdisciplinary Longitidunal Study | Student’s t test, ANOVA (Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square tests, Post hoc tests (Scheffe’s) |

| 35 |

Limburg et al. [34] Germany, Department for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy |

72 | (49.0) | Longitidunal Uncontrolled Clinical Pilot Trial |

Descriptive statistics, (MANOVA), Hedges’ g, Effect sizes. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID),. Hierarchical linear regression |

| 36 |

Dietzek et al. [35] Germany, Center for Vertigo and Dizziness, Otorhinolaryngology, Multimodal Vestibular Rehabilitation Day Care |

650 | 41-NA | Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test, ANOVA Pearson Chi-square tests | |

| 37 |

Lahmann et al. [36] Germany, German Centre for Vertigo and Balance Disorders |

547 | (54.8) | Cross-Sectional Study |

Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test Chi-square tests, Post hoc tests, Bonferroni correction, Effect sizes ( partial η2), binary logistic regression analysis omnibus test of coefficients, Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic |

| 38 |

Ferrari et al. [37] Italy, Otorhinolaryngology |

92 case- 141 control |

Paitent 23–77 (52.47), Controls 19–75 (51.39) |

Case–Control Study | Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test, Chi-square tests |

| 39 |

Rigatellia et al. [38] Italy, Otorhinolaryngology |

60 case- 60 control |

27–77 (49.6) | NA | |

| 40 |

Godemann et al. [39] Germany, Neurology and Psychiatry (patients from 8 clinics) |

93 | NA (50.3) | Prospective Longitidunal Study |

Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test, binary logistical regressions |

| 41 | Eckhardt-Henn et al. [40] Germany, Clinic for Dizziness, Department of Neurology |

68 case- 30 control |

NA (49) | Prospective Interdisciplinary Study | ANOVA, MANCOVA, Post hoc tests (LSD), Bonferroni correction, Chi-square tests, Odds-Ratios |

| 42 |

Afzelus et al. [41] Sweden, Otolarygology, general Practionari, Neurology, Psychiatry…other |

338 | 11–80 (NA) | Multidisipliner Decriptive Study | Descriptive statistics |

Ref. No: Reference Number, NOVA: univariate analysis of variance, MANCOVA: one factorial multivariate analysis of variance, LISREL: Linear Structural Relations

Terminology

This review has two main keywords: vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization. The main terminology used in the studies relevant to these concepts, is explained below.

Terminology Related to Vertigo/Dizziness

“vertigo” [28, 37, 38], “vertigo syndromes” [26, 40], “organic and non-organic (ie, medically unexplained) vertigo/dizziness syndromes” [36]. “vertigo and dizziness” [20, 21, 25, 31–36], “dizziness” [3, 24, 29].

Terminology Related to Somatoform Complaints/Somatization

“Somatoform” [35], “somatic symptom disorder” [20], “somatoform disorders” [3, 33, 36, 39], “somatization” [3, 24, 25, 27, 29–31, 36–38], “psychosomatic” [21, 34, 37, 38], “somatopsychic” [28].

Terminology Related to Psychosomatic Vertigo/Dizziness

“Functional vertigo” [34, 41], “somatoform dizziness” [26], “somatoform vertigo syndromes” [17], “functional vestibular impairment” [39], “functional dizziness” [22], “functional psychiatric vertigo” [31], “psychogenic vertigo” [16, 27], “primary somatoform vertigo and dizziness” [33], “secondary somatoform vertigo and dizziness” [32].

The Year, Country, Clinic, and Study Design of the Studies were Reviewed

The earliest studies included in this review belongs to Afzelus et al. [41] and Rigatellia et al. [38]. On the other hand, the most recent studies conducted by Habs et al. [22], Özdilek et al. [18] and Limburg et al. [34].

The countries where the selected researches were conducted were as follows: Sweden [41], Germany [3, 17, 19–22, 26, 28, 31–36, 39, 40], Italy [30, 37, 38], USA [24, 29], Portugual [27], İngiltere [23, 25], Turkey [16, 18], Belgium [15].

Most of the studies in this review were designed and conducted as prospective, cross-sectional, descriptive and/or observational. Only one study [22] was designed (database-driven study) retrospectively. On the other hand, there were also prospective case–control studies, uncontrolled clinical pilot trials, prospective longitudinal studies and therapy-efficacy studies.

Although multidisciplinary designed and conducted studies were very common, there were some single-centered studies. The clinics where the studies took place, as stated in the studies, are as folllow: “Department of Otorhinolaryngology” [15, 16, 23, 25, 37, 38], “Department of Otorhinolaryngology” and “Department of Neurology” [18, 40], “Department of Otorhinolaryngology” and “Department of Psychiatry” [28], “Department of Otorhinolaryngology”, “Department of Psychiatry” and “Department of Neurology” [27], “Department of Neurology” [3], “Department of Neurology” and “Department of Psychiatry” [39], “Department of Neurology” and “Department of Psychosomatic Medicine-Psychotherapy” [17, 26, 33], “Department of Psychosomatic Medicine-Psychotherapy” [32, 34], “Center for Vertigo and Dizziness” and “Department of Psychosomatic Medicine-Psychotherapy” [19, 20], “Center for Vertigo and Balance” [22, 24, 31, 35, 36], “Center for Vertigo and Balance”, “Psychology” and “Neurology” [21], “Walk-in clinic”, “Emergency Room”, “Internal Medicine clinic”, and “Neurology Clinic” [29], “ENT Clinic” and “Emergency Room” [30], “General Practionari”, “Ear Nose Throat Clinic”, “Neurology” and “Psychiatry” [1].

Characteristics of Participants (Number, Age and Main Complaints)

Some of the studies in this review had a control group [17, 18, 29, 30, 37, 38, 40] and the others had only study group. A total of 5490 patients and 392 controls were examined in a total number of 28 studies.

The subjects’ age range and averages were presented in some studies, [15, 17, 22, 24, 27, 30, 37], although in some studies, it (range and averages) was not presented together very clearly [33, 36, 39, 41]. Considering the studies that explicitly presented age information (with the exception of [30], the lower limit was NA in it), all of the participants included in all studies within this review, were over 18 years of age. Only one study had subjects with the age range of 11–82 [1]. The studies which were conducted on children (such as Ketola et al. [44], Emiroglu et al. [45] were not considered in this review.

In some studies, only a specific disease causing vertigo was examined, for example BPPV [18, 30, 37] and neuritis vestibularis [28, 39]. In the other, vertigo and/or dizziness were examined in general and/or in subgroups of pathologies causing vertigo and/or dizziness [3, 15, 17, 19–21, 23–27, 29, 31, 35, 36, 38, 40]. In a group of studies, the concept of “pychogenic vertigo and/or dizziness” was directly examined [16, 22, 32–34, 41].

The diagnostic evaluations and questionnaires/scales used for vertigo/dizziness, somatoform complaints/somatization and the other additional diagnosis in the studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Tools used for assessments of vertigo/dizziness, somatoform complaints/somatization and the other additional diagnosis that are included in all of the 28 studies

| Vertigo/dizziness | Somatoform complaints/somatization | Other | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic evaluations | Questionnaires/scales | Diagnostic evaluations | Questionnaires/scales | Diagnostic evaluations | Questionnaires/scales |

| aStandard vestibular tests (15, 16, 31, 32, 37, 38, 39, 41, 42) | DHI ( 22, 24) | Psychiatric examination (15, 26, 29) | SOMS (17, 41) | Neurological examination, hyperventilation provocation test, detailed cervical examination (15) | HRQOL (35, 37) |

| Electro-oculography with rotatory and caloric testing, orthoptic examination with SVV and ocular torsion (17, 20, 22, 32, 33, 37, 41) | VAP (22) | bDIS (29, 40) | SSAS (18) | Neurological examination (17) | EQ- 5D-3L (22) |

| cENG or VNG, and VEMPs (24) | VSS (17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 32, 33, 34, 36, 37, 41) | dSCID-I (17, 19, 20, 21, 26, 29, 31, 33, 34, 37, 41) | DCPR (38) | eMRI and/or X-RAY (15, 16, 27, 38, 39) | BAI (18, 20, 32, 35, 37) |

| Epley manevra (18) | VHQ (17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 32, 34, 35, 37, 41) | Pure tone audiometry and speech discrimination (16, 38, 39) | SHAI (18) | ||

| Dynamic postrography (28) | AVA (40) | PHQ (19, 20, 21, 32, 35) | Laboratory tests and electrocardiography (16, 39) | SCL-90 R (16) | |

| Neuro-otologic examination (31, 34) | VCQ (25) | WI (19, 20) | Physical examinations (19, 27) | GSI (16) | |

| Diagnostic classification of secondary SVD (33) | CABAH (19, 20) | Ophtalmologic examination (15) | HAD (17, 23, 24, 25, 36, 41) | ||

| VAS for severity of dizziness (16, 31) | SAIB (19, 20) | MINI (15) | |||

| PRIME-MD PHQ (15) | BDI-II (19, 20, 21, 27, 32, 35, 37, 38) | ||||

| SDS (39) | SF-12 (19, 37) | ||||

| BSI (38) | STAI (23, 27, 28, 30, 31, 38, 40) | ||||

| WOCQ (24) | |||||

| MHLC (25) | |||||

| MBSS (25) | |||||

| SCL-90 (27, 28, 30, 31, 34, 41) | |||||

| ACQ (28, 40) | |||||

| BSQ (28, 40) | |||||

| MOS (29) | |||||

| SRRS (29) | |||||

| SIP (29) | |||||

| The Paykel Life Events Scale (30) | |||||

| HAM-D (30) | |||||

| RS (33) | |||||

| SOC (33) | |||||

| SWLS (33) | |||||

| SF-36 (29, 34, 35) | |||||

| KLC (35) | |||||

| MI (36) | |||||

| TAS-20 (38) | |||||

| SAS (39) | |||||

| MHQ (39) | |||||

| ACA (40) | |||||

| The panic and mobility symptoms questionnaire (27) | |||||

a(positioning tests; rotatory tests; caloric tests; posturography; and, optomotoric tests, Elecronystagmograph), b DIS: Diagnostic Interview Schedule,cENG/VNG/VEMPs: electronystagmography/videonystagmography/vestinular evoked myogenic potentials,dSCID-I The Structural Clinical İnterview For DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, e MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Questionnaires/Scales.ACA: Cognitions and Avoidance, ACQ: Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire, AVA: The Acute Vertigo Appraisal, BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory, BDI-II: The Beck Depression Inventory-II, BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory, BSQ: Body Sensations Questionnaire, CABAH Cognitions about Body and Health Questionnaire, DCPR: Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research, DHI: The Dizziness Handicap Inventory, EQ- 5D-3L: EuroQoL Five-Dimensional Questionnaire, GSI: Global Symptom İndex, HAD: Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale, HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HRQOL: Health-Related Quality Of Life, KLC: Body-Related Locus Of Control, MBSS: Miller Behavioral Style Scale, MHLC: Multidimentional Health Locus Of Control, MHQ: Crown and Crip’s Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire, MI: Mobility Inventory, MINI: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, MOS: Medical Outcomes Study-Short-Form, Paykel Life Events Scale, PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire, PRIME-MD PHQ:, RS: Resilience Scale, SAIB: Scale for the Assessment of Illness Behavior, SAS: Self Anxiety Scale, SCL-90: Hopkins Symptoms Checklist, SCL-90 R Questionnaire, SDS: Zung’s Self-Depression Scale, SF-12: The short form of “The Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire”, SF-36: The Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire, SHAI: Short Health Anxiety Inventory, SIP: Sickness Impact Profile, SOC: The Sense of Coherence Scale, SOMS: Screening for Somatoform Symptoms, SRRS: Social Readjustment Rating Scale, SSAS: Somatosensory Amplification Scale, STAI: The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, SVD: Diagnostic Classification of Secondary, SVV: Subjective Visual Vertical, SWLS: The Satisfaction with Life Scale, TAS-20: Toronto Alexithymia Scale, The Panic and Mobility Symptoms Questionnaire (agoraphobia), VAP: Vestibular Activities and Participation questionnaire, VAS: Visual Analog Scale, VCQ: Vertigo Coping Questionnaire, VHQ: Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire), VSS: Vertigo Symptom Scale, WI: Whiteley Index, WOCQ: Ways of Coping Questionnaire

Statistical Analysis

It was observed that both descriptive statistics and inferrential statistics were used. The Levene’s Test was used to examine of equality of variances. To compare the averages/means and standard deviations of two related groups to determine if there is a significant difference between the two groups a paired t-test, to compare the averages/means of two independent or unrelated groups to determine if there is a significant difference between the two, an unpaired t-test were used. The Mann–Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon T-test were used as the non-parametric alternative to the t-test for independent samples, to the t-test for paired or dependent samples, respectively. Nonparametric procedures (Chi-Square-test, Fisher’s exact test).

To compare means to assess associations between categorical data, univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) or One-Way ANOVA is used. To indicate the standardised difference between two means and the effect size the value of Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, Odds-Ratios were used. One factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANCOVA) used to determine whether there are any statistically significant differences between the adjusted means of three or more independent (unrelated) groups, ANCOVA, MANOVA. For post hoc comparisons: pair-wise post hoc tests; LSD, the Scheffe’s procedure and Bonferroni correction for multiple testing were used. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is used to measure the strength of a linear association between two variables and Partial Correlation measures the strength of a relationship between two variables, while controlling for the effect of one or more other variables. In addition, specifically, some special test such as Interrater reliability Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (K), The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) were used. Estimating relationships in some studies, regression analysis or Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) were used: logistic regression [20, 29], factor analyses, hierarchical multiple regressions [23, 25, 34], binary logistic regression analysis [36, 39], Stepwise linear regression analysis [28] and SEM [32].

Main Findings

The main purpose of this review is to reveal the relationship between vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization. In this regard, the studies were classified by the main findings as follow: The studies indicating that somatoform complaints/somatization is common in patients with vertigo/dizziness [3, 15, 19–21, 27, 33, 35–38, 41]; Studies examining the relationship and showing that there is a direct or indirect relationship vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization [17, 20, 25, 26, 28–32, 36, 37, 39, 40]; A study suggesting that a direct relationship cannot be established [18].

The result of many studies has revealed that multidisiplinary approach (neuro-otology, psychiatry) should be applied in the assessment and/or intervention processes of vertigo/dizziness [3, 16–18, 20, 21, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 34, 37, 38, 40].

Dıscussıon

The main purpose of this review is to reveal the relationship between vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization. In this regard, 155 records identified through database searching and 28 studies included in the review. The first issue to mention about literature review is the heterogeneity of terms and the classifications that have changed frequently in the past. This was valid for all main key words (vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization). For example, as in our study, we saw that vertigo and dizziness were used together in some studies [20, 21, 25, 31–36] and in some other only “dizziness” [3, 24, 29] or “vertigo syndromes” [26, 40] terms were used. It was similar for somatoform complaints/somatization concepts: “Somatoform” [35], “somatic symptom disorder” [20], “somatoform disorders” [3, 33, 36, 39], “somatization” [3, 24, 25, 27, 29–31, 36–38], “psychosomatic” [21, 34, 37, 38], and “somatopsychic” [28] were some examples for those concepts. In addition, the following terms were used for the concept of psychosomatic vertigo/dizziness, which is as a type of vertigo that cannot be explained by physical reasons: “Functional vertigo” [34, 41], “somatoform dizziness” [26], “somatoform vertigo syndromes” [17], “functional vestibular impairment” [39], “functional dizziness” [22], “functional psychiatric vertigo” [31], “psychogenic vertigo” [16, 27], “primary somatoform vertigo and dizziness” [33], “secondary somatoform dizziness and vertigo” [32]. We also come with that The Bárány Society redefined chronic functional dizziness under the new name of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness in 2017 [42] and Somatization has become the current terminology for unexplained symptoms, with patients becoming preoccupied with bodily symptoms, such as nausea, dizziness, or pain [43]. The terminology used in the studies included in this review is clearly summarized and presented together.

The year, country, clinic, and design of the studies included in the review were recorded. Although there was no time restriction, the oldest studies met the search criteria were conducted by Afzelus et al. [41] and Rigatellia et al. [38], and the most recent studies conducted by Habs et al. [22], Özdilek et al. [18] and Limburg et al. [34]. This review included the studies in English and there is no criteria related to the country. However, Germany draws our attention as the country with the highest number of studies [3, 17, 19–22, 26, 28, 31–36, 39, 40]. The fact that the majority of the studies here were conducted in the specialized vertigo centers named as “Center for Vertigo…” [19–22, 31, 35, 36]. This suggests that clinics specifically established for vertigo tend to focus more on this type of multidisciplinary studies. Most of the studies in this review were designed and conducted as prospective, cross-sectional, descriptive and/or observational. Only one study [22] was retrospectively (database-driven study) designed. On the other hand, there were also prospective case–control studies, uncontrolled clinical pilot trials, prospective longitudinal studies and therapy-efficacy studies. Some of the studies in this review had a control group [2, 17, 18, 29, 30, 37, 38] and the others had only study group and a total of 5490 patients and 392 controls were examined in all 28 studies. Although these study designs have their own unique advantages, they are not provide cause-effect relationship between variables, directly. On the other hand the controlled trails could give better opportunity to control factors directly.

The diagnostic evaluations made and questionnaires/scales used for vertigo/dizziness, somatoform complaints/somatization, and the other additional diagnosis in the studies were very diverse. The most popular tools for vertigo/dizziness, somatoform complaints/somatization, and the other additional diagnosis were as follow, respectively: Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS) [17, 23–26, 31–33, 35, 36, 40], Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire (VHQ) [17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 31, 33, 34, 36, 40]; Hospital Anxiety And Depression scale (HAD), [17, 23–25, 35, 40], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) [19–21, 31, 34]; The Beck Depression Inventory-II(BDI-II) [19–21, 27, 31, 34, 36, 37], STAI [3, 23, 27, 28, 30, 37, 39], SCL-90 Hopkins Symptoms checklist [3, 27, 28, 30, 33, 40]. The diversity of the tools used for vertigo/dizziness, somatoform complaints/somatization has been revealed and summerized in this review.

The data in the studies were presented via descriptive and inferential statistics. The most used methods were comparison of means, variance analysis and correlation analysis. On the other hand in a few studies, regression analysis and SEM were used to estimate the relationships and the impact degree between variables. Those studies were as follows: Logistic regression [20, 29], hierarchical multiple regressions [23, 34], binary logistic regression analysis [36, 39], stepwise linear regression analysis [28] and SEM [32]. In this review, we have seen that such relationship-estimating analysis methods had not been widely used in these subject areas. However, we think that more qualified studies will be produced by planning to investigate relationships with advanced statistical analysis such as SEM in health research.

The studies in this review, are categorized under three groups (some studies may be seen in two different groups and some of the others are no where because of limited demonstration of their main findings). The first grup included the studies indicating that somatoform complaints/somatization is common in patients with vertigo/dizziness [3, 15, 19–21, 27, 33, 35–38, 41]. The second group composed of studies examining the relationship and showing that there is a direct or indirect relationship vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization [17, 20, 25, 26, 28–32, 36, 37, 39, 40]. The last group had only one study suggesting that a direct relationship cannot be established [18]. Moreover, other than those, in a retrospective study of a large cohort demonstrated relevant differences between primary- and secondary-PPPD patients in terms of demographic and clinical features, and propose to careful syndrome subdivision for further prospective studies [22]. In a study on disability and handicap of vertigo is investigated and multiple regression analyses indicated that disability was determined mainly by physical factors (vertigo severity and duration, age and sex), where as handicap was influenced by a mixture of somatic and psychological variables, including the severity of autonomic symptoms [23].

Eckhardt-Henn et al. 40 demostrated that the psychiatric disorder history is a strong predictor for future reactive psychiatric disorders in patients with vestibular vertigo syndrome. Especially the patients with vestibular migraine have a risk of developing somatoform dizziness [26]. In a retrospective study the most common somatic triggers for secondary functional dizziness were determined as; Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular migraine, and acute unilateral vestibulopathy [22].

In a study on persistent dizziness, it was shown that “there is an assosication with increased functional impairment and psychiatric comorbidity, particularly with depression and somatization. Moreover, psychiatric disorders aggravate the impairment that occurs with dizziness alone [29]. The degree of vestibular dysfunction is not associated with the development of psychiatric disorders. [26].

A longitidunal study on causes of vertigo one year after neuritis vestibularis [28], suggests that it should be determined whether the severity of the changed body perception and the associated interpretation behavior of patients with vertigo will lead to the development of psychiatric disorders like somatoform or anxiety disorders. In a study on persistent dizziness the need for careful syndrome classification and further prospective studies in clearly characterized primary and secondary persistent postural-perceptual dizziness subgroups has shown [22].

On the other hand, the result of many studies has revealed that multidisiplinary approach (neuro-otology, psychiatry) should be applied in the assessment and/or intervention processes of vertigo/dizziness [3, 16–18, 20, 21, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 34, 37, 38, 40]. Although it is known that this concept is widely suggested, we cannot say that we know exactly how much cooperation rains in practice. Clinics to be established specific to diseases/disorders, such as the case in Germany, and a multidisciplinary approach will provide more opportunities to focus on the subject more frequently. Future studies on the multidisiplinary approach (neuro-otology, psychiatry) to vertigo/dizziness will illuminate this issue.

Studies in this review have generally investigated psychiatric factors in patients with vertigo/dizziness. However, reviewing the studies investigating the vertigo/dizziness in psychiatric patients can provide more useful results to understand the subject. The studies on adult population included in this review. Only one study had subjects with the age range of 11–82 years [41]. Although there were studies in children (such as [45]), they were not considered in this review. This issue should be discussed separately, because the evaluation materials and evaluation criteria the approaches for the elderly may differ from children and young populations. Moreover, we think that the underlying factors may also vary between those populations. For example, in a study of older patients treated for dizziness and vertigo revealed that mainly somatic deficits prevail in the elderly instead psychological factors such as anxiety which plays a minor role compared to young and middle aged patients [35].

A specific disease causing vertigo was examined randomly studied in regard to somatization, such as PPV [18, 30, 37] and neuritis vestibularis [28, 39]. In this revew, we have not considered the subgroups of diseases causing vertigo. On the basis of subgroups, somatoform complaints and somatization should be evaluated and the results should be presented in the future. On the other hand, the concept of “psychogenic vertigo and/or dizziness” as a a type of vertigo, was directly examined in a group of study [16, 22, 32–34, 41]. This concept should be handled very carefully and its place in the classification systems should be evaluated with a multidisciplinary approach.

Conclusıon

The present study highlights the relationship between the vertigo/dizziness and somatoform complaints/somatization. It is determined that somatoform complaints of the individuals suffering from vertigo/dizziness is highly prevelant and some other factor such as personality characteristics or accompanying psychopathology have affect on the prevelance. Further more, this review has many strenghts as illuminating the following issues: (1) The studies on somatoform complaints/somatization and vertigo/dizziness were presented and their main findings were presented. (2) The assessment tools and questionnaires used for somatoform complaints/somatization and vertigo/dizziness in the study, were presented together to give an idea for future research. (3) The statistical methods used to explain the relationship between somatoform complaints/somatization and vertigo/dizziness were discussed. (4) It is necessary to carry out studies that will examine the relationship between vertigo-related diseases subgroups and somatization. (5) Multidisiplinary approach (neuro-otology, psychiatry) should be applied in the assessment and/or intervention processes of vertigo/dizziness. (6) It has been seen that there is a need for studies to determine which is the main problem in the association of vertigo/dizziness and somatoform and which one appears first.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Esra Çalış, who contributed to selection for key words and determination of search strategy.

Author Contributions

SA: Design, searching the literature, Analysing the data, and critical reading. SC; Design, searching the literature, registration to PROSPERO, Analysing the data, writing the manuscript.

Data Availability

Data available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interset

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This is a systematic review which is conducted based on publicly accessible documents as evidence. Therefore, it is not required to seek an institutional ethics approval before conducting this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Prieto L, Santed R, Cobo E, Alonso J. A new measure for assessing the health-related quality of life of patients with vertigo, dizziness or imbalance: the VDI questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(1–2):131–139. doi: 10.1023/a:1026433113262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strupp M, Brandt T. Diagnosis and treatment of vertigo and dizziness. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(10):173–180. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckhardt-Henn A, Breuer P, Thomalske C, Hoffmann SO, Hopf HC. Anxiety disorders and other psychiatric subgroups in patients complaining of dizziness. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17(4):369–388. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odman M, Maire R. Chronic subjective dizziness. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128(10):1085–1088. doi: 10.1080/00016480701805455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Hoffman RM, Einstadter D. How common are various causes of dizziness? A critical review. South Med J. 2000;93(2):160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuhauser HK, Lempert T. Vertigo: epidemiologic aspects. Semin Neurol. 2009;29(5):473–481. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1241043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV: Author

- 8.World Health Organization. (2004). ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems : tenth revision, 2nd ed. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980

- 9.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016) Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [PubMed]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5: Author.

- 11.Schaefert R, Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Häuser W, Ronel J, Herrmann M, Henningsen P. Clinical Practice Guideline: non-specific, functional and somatoform bodily complaints. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(47):803–813. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dieterich M, Eckhardt-Henn A. Neurologische und somatoforme Schwindelsyndrome. Nervenarzt. 2004;75(3):281–302. doi: 10.1007/s00115-003-1678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “Study Quality Assessment Tools [https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools].” (2019).

- 15.Persoons P, Luyckx K, Desloovere C, Vandenberghe J, Fischler B. Anxiety and mood disorders in otorhinolaryngology outpatients presenting with dizziness: validation of the self-administered PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire and epidemiology. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(5):316–323. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(03)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardiç FN, Ateşci FC. Is psychogenic dizziness the exact diagnosis? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(6):578–581. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Best C, Eckhardt-Henn A, Diener G, Bense S, Breuer P, Dieterich M. Interaction of somatoform and vestibular disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(5):658–664. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Özdilek A, Yalınay Dikmen P, Acar E, Ayanoğlu Aksoy E, Korkut N. Determination of anxiety, health anxiety and somatosensory amplification levels in individuals with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Int Adv Otol. 2019;15(3):436–441. doi: 10.5152/iao.2019.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Limburg K, Sattel H, Radziej K, Lahmann C. DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder in patients with vertigo and dizziness symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2016;91:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limburg K, Sattel H, Dinkel A, Radziej K, Becker-Bense S, Lahmann C. Course and predictors of DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder in patients with vertigo and dizziness symptoms—a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;77:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Limburg K, Dinkel A, Schmid-Mühlbauer G, Sattel H, Radziej K, Becker-Bense S, Henningsen P, Dieterich M, Lahmann C. Neurologists' assessment of mental comorbidity in patients with vertigo and dizziness in routine clinical care-comparison with a structured clinical interview. Front Neurol. 2018;13(9):957. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habs M, Strobl R, Grill E, Dieterich M, Becker-Bense S. Primary or secondary chronic functional dizziness: does it make a difference? A DizzyReg study in 356 patients. J Neurol. 2020;267(S1):212–222. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yardley L, Verschuur C, Masson E, Luxon L, Haacke N. Somatic and psychological factors contributing to handicap in people with vertigo. Br J Audiol. 1992;26(5):283–290. doi: 10.3109/03005369209076649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piker EG, Jacobson GP, McCaslin DL, Grantham SL. Psychological comorbidities and their relationship to self-reported handicap in samples of dizzy patients. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008;19(4):337–347. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.19.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yardley L. Prediction of handicap and emotional distress in patients with recurrent vertigo: symptoms, coping strategies, control beliefs and reciprocal causation. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(4):573–581. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Best C, Eckhardt-Henn A, Tschan R, Dieterich M. Psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in different vestibular vertigo syndromes: results of a prospective longitudinal study over one year. J Neurol. 2009;256:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia FV, Coelho MH, Figueira ML. Psychological manifestations of vertigo: a pilot prospective observational study in a Portuguese population. Int Tinnitus J. 2003;9(1):42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godemann F, Siefert K, Hantschke-Brüggemann M, Neu P, Seidl R, Ströhle A. What accounts for vertigo one year after neuritis vestibularis—anxiety or a dysfunctional vestibular organ? J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(5):529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Lucas CA, Rosenberg ML, Scherokman BJ. Psychiatric disorders and functional impairment in patients with persistent dizziness. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(10):530–535. doi: 10.1007/BF02599633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monzani D, Genovese E, Rovatti V, Malagoli ML, Rigatelli M, Guidetti G. Life events and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a case-controlled study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126(9):987–992. doi: 10.1080/00016480500546383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Probst T, Dinkel A, Schmid-Mühlbauer G, Radziej K, Limburg K, Pieh C, Lahmann C. Psychological distress longitudinally mediates the effect of vertigo symptoms on vertigo-related handicap. J Psychosom Res. 2017;93:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschan R, Best C, Beutel ME, Knebel A, Wiltink J, Dieterich M. Eckhardt-Henn A Patients' psychological well-being and resilient coping protect from secondary somatoform vertigo and dizziness (SVD) 1 year after vestibular disease. J Neurol. 2011;258(1):104–112. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5697-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tschan R, Best C, Wiltink J, Beutel ME, Dieterich M, Eckhardt-Henn A. Persistence of symptoms in primary somatoform vertigo and dizziness: a disorder “lost” in health care? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(4):328–333. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318288e2ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Limburg K, Schmid-Mühlbauer G, Sattel H, Dinkel A, Radziej K, Gonzales M, Ronel J, Lahmann C. Potential effects of multimodal psychosomatic inpatient treatment for patients with functional vertigo and dizziness symptoms—a pilot trial. Psychol Psychother. 2019;92(1):57–73. doi: 10.1111/papt.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dietzek M, Finn S, Karvouniari P, Zeller MA, Klingner CM, Guntinas-Lichius O, Witte OW, Axer H. In older patients treated for dizziness and vertigo in multimodal rehabilitation somatic deficits prevail while anxiety plays a minor role compared to young and middle aged patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;30(10):345. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahmann C, Henningsen P, Brandt T, Strupp M, Jahn K, Dieterich M, Eckhardt- Henn A, Feuerecker R, Dinkel A, Schmid G. Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial impairment among patients with vertigo and dizziness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(3):302–308. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrari S, Monzani D, Baraldi S, Simoni E, Prati G, Forghieri M, Rigatelli M, Genovese E, Pingani L. Vertigo “In the Pink”: the impact of female gender on psychiatric-psychosomatic comorbidity in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(3):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigatelli M, Casolari L, Bergamini G, Guidetti G. Psychosomatic study of 60 patients with vertigo. Psychother Psychosom. 1984;41(2):91–99. doi: 10.1159/000287794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godemann F, Schabowska A, Naetebusch B, Heinz A, Ströhle A. The impact of cognitions on the development of panic and somatoform disorders: a prospective study in patients with vestibular neuritis. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):99–108. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eckhardt-Henn A, Best C, Bense S, Breuer P, Diener G, Tschan R, Dieterich M. Psychiatric comorbidity in different organic vertigo syndromes. J Neurol. 2008;255(3):420–428. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afzelius LE, Henriksson NG, Wahlgren L. Vertigo and dizziness of functional origin. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(4):649–656. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staab J, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, Jacob R, Strupp M, Brandt T, Bronstein A. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): consensus document of the committee for the classification of vestibular disorders of the Bárány society. J Vestib Res. 2017;27:1–18. doi: 10.3233/VES-170622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGeary DD, Hartzell MM, McGeary CA, Gatchel RJ. Somatic disorders. In: Norcross JC, VandenBos GR, Freedheim DK, Pole N, editors. APA handbook of clinical psychology: Psychopathology and health. USA: American Psychological Association; 2016. pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ketola S, Niemensivu R, Henttonen A, Appelberg B, Kentala E. Somatoform disorders in vertiginous children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(7):933–936. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emiroğlu FN, Kurul S, Akay A, Miral S, Dirik E. Assessment of child neurology outpatients with headache, dizziness, and fainting. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(5):332–336. doi: 10.1177/088307380401900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.