Abstract

Allergic Rhinitis (AR) is an inflammatory condition of the nasal mucosa triggered by Immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated response to exposure to allergens. The most common symptoms are nasal obstruction, sneezing, runny nose and these in addition to swollen, itchy, red and watery eyes. Recent studies have shown highly elevated immunoglobulin E levels in the airway mucosa independently of serum IgE levels and atopic status. Nasal mucosa has intrinsic capability to produce IgE in allergic rhinitis. The study was conducted to explore the levels of nasal total IgE and serum total IgE and their correlation in symptomatic AR patients. This was a case control-study and two groups participated in the study. The first group included 203 symptomatic patients who were diagnosed in the otorhinolaryngology clinic as cases of AR, known as AR group. The second group was control group and included 203 apparently healthy volunteers without any history suggestive of AR. The associated risk factors for severe allergic symptoms were assessed by logistic regression model. The mean differences between nasal total IgE and serum total IgE levels of both groups were compared by t-test. A correlation was investigated between nasal IgE and serum IgE in both the groups. The mean level of nasal total IgE and serum total IgE was found to be 103.9 and 291.4 IU/ml in AR group, respectively, and 17.5 and 67.5 IU/ml in the control group, respectively. Levels of nasal total IgE and serum total IgE were significantly higher in the nasal fluids and serum of symptomatic allergic rhinitis patients than in controls (p < 0.001 and < 0.001 respectively). A logistic regression model showed severity of allergic rhinitis was significantly associated with nasal total IgE levels. The correlation of nasal total IgE levels with serum total IgE levels in the control group was found to be statistically insignificant. However a statistically positive correlation was observed between nasal total IgE and serum total IgE levels in the AR group. It is possible that nasal IgE and serum IgE interact in the pathogenesis of AR and this is evident in the current study. Nasal IgE levels should be evaluated in severe symptomatic allergic rhinitis patients. The interaction between nasal IgE to serum IgE levels should be further investigated in AR patients for other possible prevalent endotypes of AR.

Keywords: Immunoglobulin E, IgE, Inflammatory markers, Allergic rhinitis, Allergy, Atopy

Introduction

Rhinitis is a generic term describing nasal symptoms resulting from inflammation and/or dysfunction of nasal mucosa. Allergic Rhinitis (AR) is characterized by sneezing, nasal congestion, nasal itching, nasal discharge and is triggered by Immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated response to exposure to allergens [1].The prevalence of AR has increased significantly since the 1990s. It is reported to affect approximately 25% and 40% of children and adult globally, respectively [2]. AR and asthma appear to have increased in India over the past decades and approximately 22% of adolescents currently suffer from AR in India [3].

AR classification is based on symptoms’ duration (intermittent or persistent) and severity (mild and moderate to severe). Intermittent AR is defined as symptoms occurring for four days or less per week for less than four weeks, whereas the patient suffers for most of the year in persistent class of disease. Mild symptoms do not interfere with the patient’s ability to sleep and function normally, but sleep is significantly affected and patient becomes morbid in moderate to severe symptoms [4].

The involvement of IgE is importantly exists in the early phase allergic response, and also involved in the late phase response. The serum levels of IgE in non-allergic individuals when compared with the other class of immunoglobulins is the lowest. However, half of the IgE molecules are in the tissues (respiratory mucosa, gastrointestinal tract, and skin) bound to cells, in particular, mast cells, which accounts for its important role in immediate hypersensitivity reactions and allergic inflammation [5]. IgE can be highly elevated in the airway mucosa irrespective of serum IgE levels or atopic status and IgE that is locally produced in the target organ could have therapeutic and diagnostic importance in AR [6]. Measurement of total serum IgE is a simple and inexpensive investigation which has been used for its diagnostic role for allergic disorders such as rhinitis and asthma. However, it is not routinely performed as other secondary factors such as environment, location, age, sex and smoking, prior sensitization alter the baseline total serum IgE levels [7].

More recently, studies have shown the presence of local allergic rhinitis, a localized allergic response often present with symptoms typical of AR in the absence of systemic atopy characterized by local production of specific IgE antibodies and Th2 mucosal cell infiltration during the natural exposure to allergens [8]. A literature search has shown fewer studies regarding the comparison or correlation of nasal total IgE with other inflammatory biomarkers in symptomatic AR patients.

Hence, this present study aims at examining the mean total nasal IgE and mean serum total IgE levels, correlation of nasal IgE and serum IgE in symptomatic AR patients in India, in an attempt to evaluate for a possible association.

Material and Methods

This study was a case–control study conducted at a tertiary care military hospital in Visakhapatnam, India from May 2022 to July 2023 after obtaining ethical approval from the institutional ethics committee (07/Tec/Kal dated 10 May 2022). A written informed consent was obtained from each subject participating in the study.

The first group comprised of 203 symptomatic AR patients presenting with rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction as the main complaints according to “Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma” (ARIA) guidelines [4]. The AR patients were diagnosed in a well equipped otorhinolaryngology OPD clinic by the first author as having AR and nasal endoscopy was performed on every patient to exclude other conditions such as acute or chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis and nasal septal deviation. The second group comprised of 203 healthy volunteers who visited otorhinolaryngology clinic without any history of AR and considered as control group.

The patient’s sex, age, duration of symptoms, body mass index (BMI) and severity were recorded. Age, sex and BMI were matched with the control group. Detailed history of therapeutic drug use and any systemic diseases were recorded from patients and healthy controls. If any patients and controls with a history of taking corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bronchodilators, mast cell stabilizers, immunosuppressants during the last 2 months, evidence of asthma and smoking were not enrolled. Both groups enrolled had blood tests and nasal fluid tests in order to determine their serum total IgE and nasal total IgE, respectively. Serum total IgE and nasal total IgE were measured by the immunoassay method (Agappe Diagnostics Ltd, India). AR is classified as moderate to severe if one or more of the following are present: abnormal sleep, impairment of daily activity, abnormal work at school, or troublesome symptoms and if none of the above symptoms are present it is regarded as mild [4].

Inclusion criteria included patients with AR diagnosed in otorhinolaryngology OPD clinic by the first author and with age ranging between 18 and 50 years.

Exclusion criteria involved AR patients who had a body mass index (BMI) more than 25 kg/m2, patients suffering from chronic inflammatory or immunological conditions such as chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and patients receiving chronic or recent therapy with medication such as steroids, antihistamines or omalizumab.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic data was presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of mean (SEM) where indicated. Student’s independent t-test for data comparison was performed. A binary logistic regression model was used to determine the variables associated with severity of allergic rhinitis. Pearson correlation was used to analyze the relation between the studied parameters. P-value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analysis was carried out by using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Results

The study sample included 406 subjects divided into two groups with 203 patients in AR group and 203 healthy volunteers in control group. The AR group included AR patients of the same age, sex and BMI as the control group. The demographic characteristics of the studied population from both groups are summarized in Table 1, which represent age, sex, weight and BMI status. 105 (52%) patients in AR group had moderate to severe intermittent or moderate to severe persistent AR.

Table 1.

Characteristics of control group and AR group

| Studied sample | Studied characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Number (M/F) | Weight (Kg) | BMI(Kg/M2) | |

| Control group | 30.08 (± 7.8) | 203 (113/90) | 64.3 ± 7.6 | 23.4 ± 1.3 |

| AR group | 30.04(± 8.4) | 203 (118/85) | 65.1 ± 8.1 | 22.6 ± 1.8 |

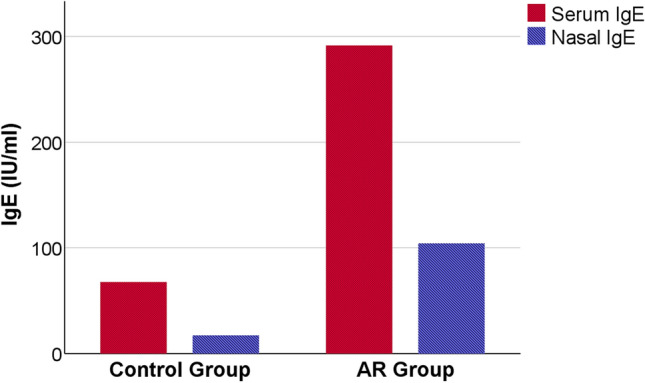

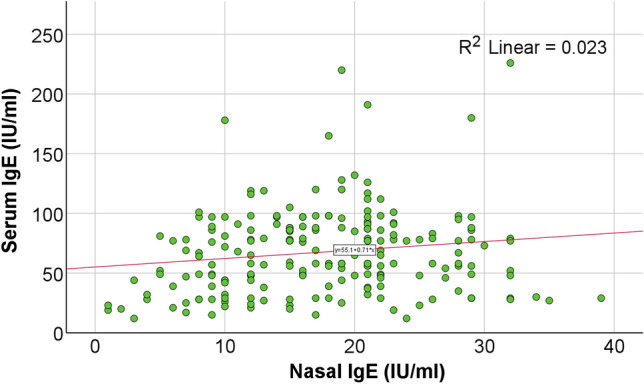

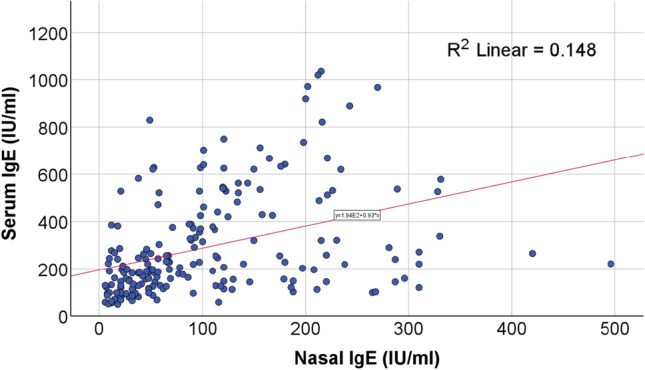

The mean level of serum total IgE and nasal total IgE was found to be 67.5 and 17.5 IU/ml respectively, in the control group and 291.4 and 103.9 IU/ml respectively, in the AR group. The prevalence of high levels of nasal IgE and serum IgE in the AR group was significantly higher than the control group (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively), as illustrated in Fig. 1. The correlation of nasal total IgE levels with serum total IgE levels in control group was found to be statistically insignificant (P > 0.05). The correlation coefficient (r) variable was 0.152, and does not reflect a significant correlation between the two variables, illustrated in Fig. 2. However a statistically significant positive correlation was observed between nasal total IgE and serum total IgE levels in the AR group. The correlation coefficient (r) between the variables is 0.385 which reflects a positive correlation between the two variables, shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 1.

Serum IgE and nasal IgE levels in Control group and AR group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Independent samples t-test was used for statistical comparison between both groups. P < 0.001 represents a difference of statistical significance between control and AR groups for both serum IgE and nasal IgE levels

Fig. 2.

Correlation between Nasal IgE and Serum IgE levels in Control group. Statistically non-significant correlation (p > 0.05) with Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.152) is shown in the control group

Fig. 3.

Correlation between Nasal IgE and Serum IgE levels in AR group. Statistically significant correlation (p < 0.001) with Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.385) is shown in the AR group

Binary logistic regression was done to predict the variables such as age, sex, serum total IgE levels and nasal total IgE levels associated to cause severe AR. It was evaluated that elevated nasal total IgE levels in the AR group were associated to cause severe AR with statistical significance (P value < 0.001).

Discussion

IgE is one of the most important markers for most of the types of allergic diseases. IgE has an important role in allergy sensitization in atopic disorders such as allergic rhinitis, asthma and atopic dermatitis. The symptoms of AR are triggered by inflammatory mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes released as a result of increased IgE production from plasma cells. Exposure of the nasal mucosa to exogenous allergens causes inflammatory T cells to invade the nasal mucosa and release cytokines which trigger a further cellular inflammatory response over the next 4–8 h (late-phase inflammatory response) which results in recurrent nasal symptoms [9].

Serum IgE may not necessarily reflect the systemic IgE levels since most local IgE is bound by its receptors. The pool of IgE in an individual is the sum of IgE produced against different allergens (specific IgE). It was observed in most studies that the probability is very high in predicting allergy when the total serum IgE level is above 200ku/l. Nevertheless, a high total serum IgE level alone is of limited value of allergy as it does not give any clue regarding sensitizing allergens [10]. Serum IgE in AR might be a result of spill over of locally produced IgE from mucosal sites rather than reverse. A series of cell separation experiments performed by Eckl-Dorna group found that majority of circulating specific IgE antibodies are not derived from IgE producing cells in the blood, and suggests that IgE production at target organ is the probable cause [11]. AR patients with negative skin prick testing and suggested as non-allergic rhinitis or idiopathic rhinitis are infact allergic as this small subgroup of patients have localized cellular pathogenesis with measurable specific IgE in their nasal secretions [12].

It was observed from the experiments that after re-exposure local IgE increased more rapidly than the serum IgE [13]. In some experiments levels of specific IgE measured in nasal secretions was more than the levels measured in the serum of AR patients to cedar pollen. In another experiment where no specific IgE was measurable in the serum, elevated levels were found in the nasal secretions [14, 15]. An experiment by Gokkaya et al. in 47 subjects and 2 controls showed significant positive correlation between nasal specific IgE and serum specific IgE [16]. On literature search, there are no studies available that describe the levels of total nasal IgE and total serum IgE or their correlation in symptomatic AR patients. Accordingly the present study was done to bridge the gap.

An increasing prevalence of AR and asthma has been reported in the Indian subcontinent. India has highest concentration of air pollution caused by biomass, fossil fuels, vehicular exhausts and particulate matter exceeding the limits of 40 μg/m3. It is difficult to study Indian population based on published evidence generated from western countries because of environmental confounders such as air pollution and parasitic infection. Parasitic infection is particularly relevant while evaluating biomarkers such as peripheral blood eosinophils and serum total IgE [17].

This study was carried out to explore the relationship between nasal total IgE levels and serum total IgE levels in symptomatic AR patients and in healthy controls. The study revealed that the mean levels of nasal total IgE and serum total IgE in the symptomatic IgE patients was significantly more than the controls group (p < 0.001), shown in Fig. 1. 105 (52%) of the patients were diagnosed as having severe allergic disease. The variables such as age, sex, nasal total IgE and serum total IgE levels were studied with binary logistic regression analysis for their any predictable association to cause severe nasal symptoms. Our regression model predicted elevated nasal IgE levels to cause severe nasal symptoms with statistical significance (p < 0.001). Our study group with symptomatic AR patients might be chronic rhinitis patients resulting from IgE-sensitization from environmental allergens or non-allergic rhinitis group where immune mediated response was not always present [18] or local allergic rhinitis group where there was negative skin prick test, but respond to nasal allergen provocation test. Most of the patients out of 105 severe symptomatic AR patients in our study group, might be suffering from local AR since moderate to severe intermittent/persistent symptomatic patients are most likely from local AR patients [19]. There might also be mixed conditions constituted by these allergic endotypes where diagnosis of allergic nasal conditions are challenging in routine clinical practice.

Nasal IgE is not routinely measured in clinical practice although the discovery of nasal IgE defined as local production of IgE in the nasal mucosa has been widely reported. Contrary to these findings some other studies found no prevalence of nasal IgE in non-allergic rhinitis [20]. Our study showed statistically significant positive correlation between nasal IgE and serum IgE in AR group, whereas control group showed statistically insignificant correlation as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Conclusion

The mean nasal total IgE and mean serum total IgE levels are significantly elevated in symptomatic AR patients when compared to the healthy controls. Nasal IgE and serum IgE interact in the pathogenesis of AR. This is evident in the current study as there was significant correlation between nasal IgE and serum IgE levels. Elevated nasal IgE levels are associated with severe allergic nasal symptoms; hence it is recommended that nasal IgE levels should also be evaluated in severe symptomatic AR patients. The interaction between nasal IgE to serum IgE levels should be further investigated in AR patients for prevalence of other possible endotypes of AR.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All medical and surgical interventions performed in this study involving the human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bousquet J, Anto JM, Bachert C, Baiardini I, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Walter Canonica G, et al. Allergic rhinitis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2020;6:95. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nur Husna SM, Tan H-TT, Md Shukri N, Mohd Ashari NS, Wong KK (2022) Allergic rhinitis: a clinical and pathophysiological overview. Front Med 9:874114. 10.3389/fmed.2022.874114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Moitra S, Mahesh PA, Moitra S. Allergic rhinitis in India. Clin Exp Allergy. 2023;53:765–776. doi: 10.1111/cea.14295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008*: ARIA: 2008 update. Allergy. 2008;63:8–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poole JA, Rosenwasser LJ. The role of Immunoglobulin E and immune inflammation: implications in allergic rhinitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005;5:252–258. doi: 10.1007/s11882-005-0045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Schryver E, Devuyst L, Derycke L, Dullaers M, Van Zele T, Bachert C, et al. Local Immunoglobulin E in the nasal mucosa: clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2015;7:321. doi: 10.4168/aair.2015.7.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung D, Park KT, Yarlagadda B, Davis EM, Platt M. The significance of serum total immunoglobulin E for in vitro diagnosis of allergic rhinitis: the significance of serum total IgE. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:56–60. doi: 10.1002/alr.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rondón C, Campo P, Togias A, Fokkens WJ, Durham SR, Powe DG, et al. Local allergic rhinitis: concept, pathophysiology, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1460–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Small P, Kim H. Allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma. Clin Immunol. 2011;7:S3. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amarasekera M. Immunoglobulin E in health and disease. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:12–15. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckl-Dorna J, Pree I, Reisinger J, Marth K, Chen K-W, Vrtala S, et al. The majority of allergen-specific IgE in the blood of allergic patients does not originate from blood-derived B cells or plasma cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1347–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rondón C, Doña I, López S, Campo P, Romero JJ, Torres MJ, et al. Seasonal idiopathic rhinitis with local inflammatory response and specific IgE in absence of systemic response. Allergy. 2008;63:1352–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sensi LG, Piacentini GL, Nobile E, Ghebregzabher M, Brunori R, Zanolla L, et al. Changes in nasal specific IgE to mites after periods of allergen exposure-avoidance: a comparison with serum levels. Clin Htmlent Glyphamp Asciiamp Exp Allergy. 1994;24:377–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1994.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida T, Usui A, Kusumi T, Inafuku S, Sugiyama T, Koide N, et al. A Quantitative analysis of cedar pollen-specific immunoglobulins in nasal lavage supported the local production of specific IgE, not of specific IgG. Microbiol Immunol. 2005;49:529–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huggins KG, Brostoff J. Local production of specific IgE antibodies in allergic rhinitis patients with negative skin tests. Lancet. 1975;306:148–150. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gökkaya M, Schwierzeck V, Thölken K, Knoch S, Gerstlauer M, Hammel G, et al. Nasal specific IgE correlates to serum specific IgE: first steps towards nasal molecular allergy diagnostic. Allergy. 2020;75:1802–1805. doi: 10.1111/all.14228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishna MT, Mahesh PA, Vedanthan PK, Mehta V, Moitra S, Christopher DJ. The burden of allergic diseases in the Indian subcontinent: barriers and challenges. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e478–e479. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadopoulos NG, Guibas GV. Rhinitis subtypes, endotypes, and definitions. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2016;36:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terada T, Kawata R. Diagnosis and treatment of local allergic rhinitis. Pathogens. 2022;11:80. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckrich J, Hinkel J, Fischl A, Herrmann E, Holtappels G, Bachert C et al (2020) Nasal IgE in subjects with allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. World Allergy Organ J 13:100129. 10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]