Abstract

Extraosseous plasmacytoma, a rare plasma cell neoplasm, was observed in a 52-year-old male with uncommon presentation in the oropharynx with cervical lymph node involvement. The patient presented with dysphonia and left neck swelling. This case report primarily focuses on the management, resulting in a successful treatment through radiotherapy.

Keywords: Plasmacytoma, Oropharynx, Dysphonia, Lymph node, Radiotherapy

Introduction

Plasmacytoma is a malignant proliferation of plasma cells that is subdivided into solitary plasmacytoma of bone and extraosseous plasmacytoma (EP). EP constitutes 3–5% of plasma cell neoplasms [1]. EP arises outside the bone marrow, with 80% occurring in the upper respiratory tract, including the oropharynx [1]. Available treatments options for EP include radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy. Nevertheless, there are currently no randomized studies to establish the most effective treatment approach [2]. Despite this, radiation therapy is considered the treatment of choice for managing EP [2–4].

Case Report

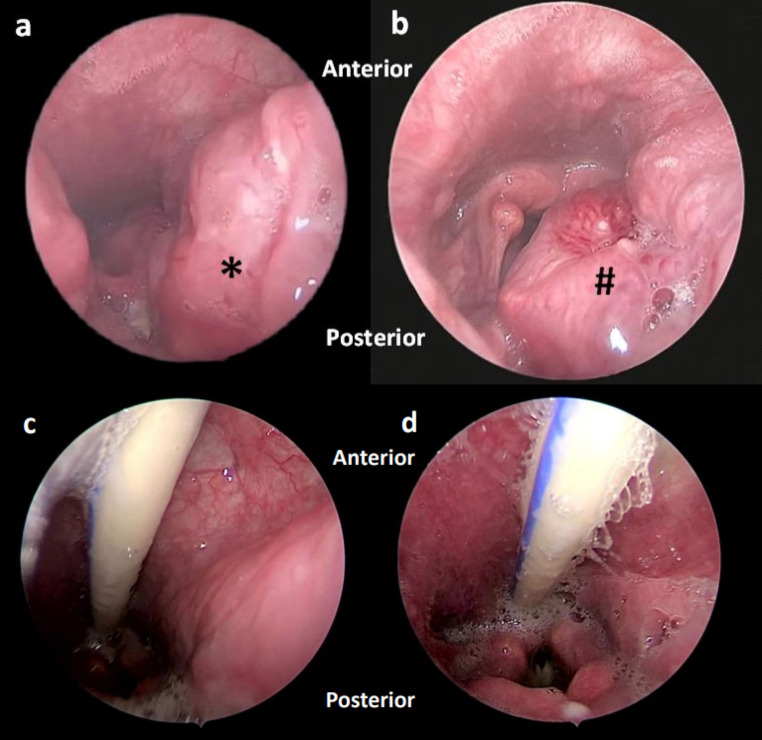

A 52-year-old non-smoker male presented with a 6-month history of a harsh voice, followed by a foreign body sensation upon swallowing, painless left neck swelling, and constitutional symptoms. Intra-orally, a mass was seen at the left oropharynx, causing the uvula to be displaced to the opposite side. During a neck examination, a firm 3 × 4 cm swelling was identified at left level II. Direct laryngoscopy revealed that the mass originated from the left tonsil and extended posteriorly (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a and b: Rigid direct laryngoscopy view of a mass arising from the left tonsil extending to the hypopharynx(*). The mass (#) abuts supraglottic structures posteriorly, obstructing the laryngeal inlet; c and d: Follow up was observed 2 months after radiotherapy

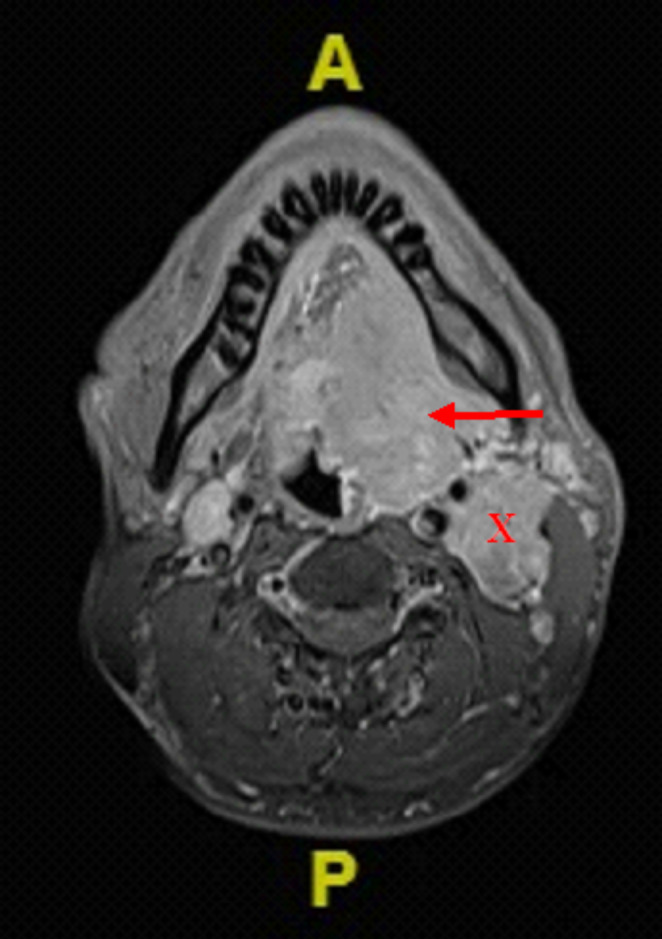

The MRI of the neck revealed an aggressive left oropharyngeal enhanced mass with an enlarged lymph node (Fig. 2). There is no evidence of lytic bone lesions by CT scan. Microscopic examination of the mass showed diffuse plasma cells infiltration, replacing the native lymphocyte population. The cells were immunoreactive to CD138 and had kappa light chain restriction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Head and neck MRI of the axial section T1-weighted showed a left oropharyngeal contrast-enhanced mass centered on the left tonsillar fossa (red arrow) measuring 5.4cmx3.2cmx5.8 cm with an enlarged and matted contrast-enhanced left lymph node (X), immediately posterior to the left carotid sheath and deep to the deep lobe of the left parotid gland, measuring 3.4cmx2.8cmx4.4 cm

Fig. 3.

A : diffuse plasma cells infiltration exhibiting eccentric located nuclei with eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E, 100x). B : CD138 positive stain in the tumour cells, with different intensities. Confirming plasma cell linage. These cells are also negative for CD20, CD3 and CD56 (not shown). It has been reported that CD56 is often negative in extraosseous plasmacytoma [1] (40x). C : Kappa light chain (40x). D : Lambda light chain (40x). The different intensity and distribution of kappa compared to lambda staining indicated kappa light restriction. This observation is important for excluding reactive plasma cells

We opted for chemotherapy, consisting of Bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2 on day 1,4,8,11) in combination with dexamethasone (20 mg on day 1,2,4,5,8,9,11,12 of each cycle) as the initial approach. This decision was made because surgical intervention was considered less favourable for the extensive mass and the patient did not agree to radiotherapy. However, the tumour size did not change much after undergoing two cycles of chemotherapy. Consequently, we decided to proceed with radiotherapy with the patient’s agreement. A tracheostomy was performed before initiating the treatment to ensure airway safety as potential airway blockage due to oedema in the region. The patient received a total of 50 Gy in 25 fractions of radiation, and the swelling completely subsided. The patient was supported with Ryle’s tube feeding for nutritional support throughout the radiotherapy course. During regular follow-up, no clinical evidence of residual disease was observed.

Discussion

EP is an uncommon disease characterized by the localized proliferation of malignant monoclonal plasma cells that arise outside the bone. EP represents 34% of plasmacytoma [5], and 77% occurs in the head and neck [6], where it occurs most frequently in the oropharynx or nasopharynx [3, 5] as in our patient. Nodal involvement of EP was reported in 15% of head and neck primary tumours [7, 8]. 68% were male and the mean age was in the fifth decade of life [6]. Our patient is a male who falls in the mean age group.

The symptoms of EP are tied to the location of the mass, and 45–80% involve the upper respiratory tract [8]. EP involving the oropharynx is rare and presents as a unilateral mass. The symptoms depend on the size of the mass and whether it is due to obstruction or compression of nearby structures. Our patient presented with a change of voice and a foreign body sensation on swallowing. If the mass enlarges, he might have an airway obstruction.

Tissue biopsy and monoclonality of the tumour are necessary in diagnosing EP. The histopathology criteria are a monopopulation of pleomorphic plasma cells infiltration that exhibit light chain restriction, minimal lymphocyte admixture, and no evidence of lymphoepithelial lesion [7]. The cells typically express CD138 and/or CD38. The monoclonality of the tumour can be confirmed by kappa/lambda light chain restriction. Kappa light chain restriction was found in 60% of tumour, while lambda light chain restriction was found in 40% [7]. The monoclonality can also be proved by a PCR-based approach [9], but it is not available in our centre. Additional immunohistochemistry studies such as CD56, cyclin D1 and MUM1, can also be used. However, CD56 and cyclin D1 are often negative in EP as compared to multiple myeloma [1].

CT scanning is useful for loco-regional staging with lymph node involvement. CT can detect lytic bone lesions to rule out bone involvement [9] as in our patient, no lytic lesion in the bone can be seen. While soft tissue and bone marrow lesions are detected using MRI. However, there isn’t yet a report for the exclusive description of plasmacytoma in imaging. Whereas the positron emission tomography scan provides additional information to detect additional soft tissue involvement [9].

The management of EP is very challenging due to its rarity. EP is highly radiosensitive tumour [9]. There is a successful treatment of EP in the head and neck with radiation therapy [4]. However, extensive tumour in the oropharynx, as in our patient, can cause adverse reactions like tumour oedema, which can cause airway obstruction. So, radiotherapy is not our first treatment modality for this patient, and the patient was not keen on tracheostomy initially. Another treatment for EP is surgery. However, it was not practical for our patient in view of the extensive mass that required wide local excision, including total glossectomy, laryngectomy, bilateral neck dissection and mandible resection. It will negatively affect the patient’s functional outcome. We decided to choose chemotherapy as the first treatment for this patient based on the justification of safer, more practical, remission, good quality of life afterwards, and more importantly, consented by the patient. We used a combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone that are usually used in relapsed multiple myeloma, but not many cases report regarding its usage as the primary treatment for EP. Adjuvant chemotherapy may be considered for persistent disease after radiotherapy [9]. However, the patient showed no response after completing 2 cycles of chemotherapy. We decided to proceed with radiotherapy, which is the best option available for the patient in view of EP being radiosensitive, although there is no established protocol available for radiotherapy in EP [2, 4, 10, 11]. The patient finally agreed to tracheostomy insertion prior to radiotherapy for airway protection. The patient was treated with a dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions of radiation and had a good response to the dosage given.

For the prognosis, EP has a lower rate of progression to MM compared to SP [9]. Persistent serum monoclonal proteins after one year of radiation therapy indicate a higher risk for MM progression [2, 9]. Although our patient has a lower conversion rate to MM, he requires regular follow up afterwards. EP is a rare disease that is curable. A multidisciplinary approach is important for the diagnosis and holistic approach of patients.

Funding

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical Standards and Approval

The study was performed in accordance with ethical standards as in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and not required approval by the Ethical Committee of the Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Informed Consent

Patient has given informed consent to publish their information and images.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Caers J, Paiva B, Zamagni E, Leleu X, Bladé J, Kristinsson SY, Touzeau C, Abildgaard N, Terpos E, Heusschen R, Ocio E, Delforge M, Sezer O, Beksac M, Ludwig H, Merlini G, Moreau P, Zweegman S, Engelhardt M, Rosiñol L. Diagnosis, treatment, and response assessment in solitary plasmacytoma: updated recommendations from a european Expert Panel. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/S13045-017-0549-1/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Waal EGM, Leene M, Veeger N, Vos HJ, Ong F, Smit WGJM, Hovenga S, Hoogendoorn M, Hogenes M, Beijert M, Diepstra A, Vellenga E. Progression of a solitary plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma. A population-based registry of the northern Netherlands. Br J Haematol. 2016;175(4):661–667. doi: 10.1111/BJH.14291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diagnosis and management of solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma - UpToDate. Retrieved July 15, (2023) from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/solitary-extramedullary-plasmacytoma

- 4.Finsinger P, Grammatico S, Chisini M, Piciocchi A, Foà R, Petrucci MT. Clinical features and prognostic factors in solitary plasmacytoma. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(4):554–560. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerry D, Lentsch EJ. Epidemiologic evidence of superior outcomes for extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013;148(6):974–981. doi: 10.1177/0194599813481334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gholizadeh N, Mehdipour M, Rohani B, Esmaeili V, Author C (2016) Extramedullary Plasmacytoma of the oral cavity in a Young Man: a Case Report. In J Dent Shiraz Univ Med Sci (Vol. 17, Issue 2) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Grammatico S, Scalzulli E, Petrucci MT. Solitary Plasmacytoma. Mediterranean J Hematol Infect Dis. 2017;9(1):2017052. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2017.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merza H, Sarkar R. Solitary extraosseous plasmacytoma. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4(9):851–854. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strojan P, Šoba E, Lamovec J, Munda A. Extramedullary plasmacytoma: clinical and histopathologic study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(3):692–701. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues – IARC. Retrieved July 3, (2023) from https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/who-classification-of-tumours-of-haematopoietic-and-lymphoid-tissues-2/

- 11.Zhu X, Wang L, Zhu Y, Diao W, Li W, Gao Z, Chen X. Extramedullary Plasmacytoma: long-term clinical outcomes in a single-center in China and Literature Review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100(4):227–232. doi: 10.1177/0145561320950587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]