Abstract

Introduction

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea results from breakdown in the integrity of structures separating the subarachnoid space and nasal cavity, namely subarachnoid space and dura mater, the bony skull base and periostea alongside the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa. Endoscopic repair is considered the treatment of choice for CSF rhinorrhea. Our aim of study was to analyze the etiopathogenesis and outcomes of treatment.

Material and Methods

A retrospective study review of patients treated with endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea at tertiary care hospital in ENT Department Benazir Bhutto hospital Rawalpindi from august 2013 to September 2017 identified 25 patients. Majority of them were male. The defects were closed in three layers using fat, fascia lata and nasal mucosa along with fibrin sealant in majority of patients. Pre operatively subarachnoid drain was placed in all patients. Patients were followed up to 3 months.

Results

Forty-four patients underwent endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea. The age group ranged from 16 to 55 years. Of the total of 44 patients 26 (59%) were males and 18(41%) females. The mean age of the patients in our study was 32.8 ± 9.7. Post trauma CSF leak was seen up to 52.3% of the patients. The most common site of leakage was identified Cribriform plate area. Our success rate of endoscopic repair was 88.6%. The most commonly observed complication was meningitis that was observed in 2 (4.5%) of the patients that too were managed conservatively.

Conclusion

Accurate localization of site of leakage appears to be essential for successful endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea. In our study cribriform plate area was commonly observed area of CSF leak. In our study, the success rate was 88.6% and low complication rate 4.5%.

Keywords: CSF rhinorrhea, Trans-nasal Endoscopic repair, Dural defect

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea (CSF), classically described as the leakage of CSF from the nose, indicates an opening of arachnoid and dura with an osseous defect leading to a communication of subarachnoid space with the nose [1]. It is often caused by trauma (head trauma and iatrogenic insult), followed by idiopathic, congenital, and neoplastic lesions [2]. Common sites of the defect include the frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses as well as the cribriform plate [3]. Symptoms unique to the presence of CSF rhinorrhea include clear, colorless, usually unilateral nasal discharge. Other presenting symptoms are due to the underlying etiology [4]. It is classically positional in nature and exacerbated by dependent head positioning (i.e., “reservoir sign”). Patients may note salty or sweet tasting postnasal drainage [5]. Beta-2 transferrin protein and high-resolution CT scan helps in diagnosis. CSF leaks of the anterior skull base present one of the most difficult challenges in Endonasal endoscopic surgery (EES) involving an area that is anatomically complicated and technically demanding to access [6].

The credit for the first surgical repair of CSF leak goes to Dandy who closed a cranio-nasal fistula using a frontal craniotomy approach in 1926. A success rate of 60 to 80% was achieved using this approach [7]. Wigand revolutionized endoscopic CSF rhinorrhea management with his repair. Since than improved surgical techniques with better visualization have led to success rates of over 90% with lower morbidity when compared to more traditional intracranial techniques [7, 8].

Endoscopic intranasal fistula repair is now the preferred approach. Generally, a small defect can be closed with an overlay free mucosal graft or a free fascial graft. Free mucosal grafts can be acquired from the inferior turbinate or the septum. Fascia is harvested from the temporalis region or fascia lata. It is important that the mucosa surrounding a defect be removed prior to grafting to stimulate osteogenesis and to increase the channels of graft take up. Large bony defects are sealed with the help of bone grafts placed in an overlay fashion with a layer of fascia covering it in on overlay manner.

Materials and Methods

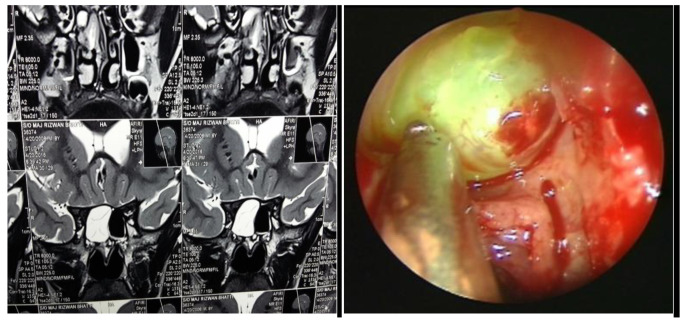

We retrospectively studied 26 patients with CSF rhinorrhea treated in ENT and Head &Neck surgery department Benazir Bhutto Hospital of Rawalpindi medical university Rawalpindi between 2014 and August 2017. Data collected included presenting signs and symptoms, site and size of skull base defect, surgical approach, repair technique and clinical follow-up. Pre-operative evaluation consisted of thorough history, physical examination, nasal endoscopic examination and radiographic images (Fig. 1). To obtain adequate anterior exposure, any agger nasi cells or concha bullosa were excised and turbinectomies and ethmoidectomies were performed when needed for exposure. Intrathecal fluorescein endoscopy was most commonly used as an adjunct to intraoperative localization of a skull-based defect. The process involved standard lumbar puncture followed by withdrawal of 10 cc of CSF, which was mixed with 0.2–0.25 cc of 5% Fluorescein. After 30 min, a brilliant yellow fluid leaking into the nose is observed. The site of leak was identified using 0º and 30º endoscopes (Fig. 2). When no leak was visible intraoperatively, the anesthetist was asked to hyperventilate in order to increase the intracranial pressure. After identifying the defect, the graft was taken by harvesting the fascia lata or temporalis fascia. The bed was prepared by removing a cuff of normal mucosa for 3–4 mm surrounding the defect. The defects were closed in three layers using fat, fascia lata and nasal mucosa along with fibrin sealant in majority of patients. Larger bony defects were reconstructed by sealing with cartilage grafts taken from the septum, shaped to the size of the defect and placed in an underlay fashion in the epidural space followed by an overlay soft tissue graft. This was followed by surgicel, gelfoam and BIPP, (bismuth iodoform paraffin and paste) packs. In the postoperative period all patients were subjected to strict bed rest, head end elevation, cough suppressants and stool softeners apart from broad spectrum antibiotic coverage. Acetazolamide and/or lumbar drainage was tried with the intention of preventing recurrence and ensuring faster healing. Nasal pack was removed after 3–5 days. Adjuvant therapy included the use of acetazolamide.

Fig. 1.

MRI scan showing the site of CSF leak. Figure 1b. Endoscopic picture via Trans-nasal route showing site of CSF leak

Fig. 2.

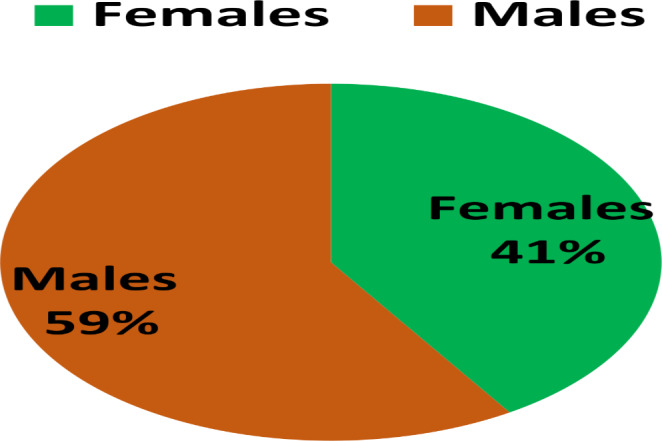

Showing gender-wise distribution of the cases

Results

Forty-four patients underwent endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea. The age group ranged from 16 to 55 years. Of the total of 44 patients 26 (59%) were males and 18(41%) females. The mean age of the patients in our study was 32.8 ± 9.7. The pictorial presentation of the gender-wise distribution of the cases are given in Fig. 2.

Etiologies of cases of CSF rhinorrhea included 23 (52.3%) post-traumatic leaks, 11 (25%) iatrogenic leaks. Spontaneous onset of CSF leak was seen up to 10 (22.7%) of the patients. Hence most common cause of leakage was trauma followed by iatrogenic and spontaneous leak. The data about etiologies of CSF rhinorrhea is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Showing the distribution of etiologies of CSF rhinorrhea

| Variables | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Traumatic | 23 | 52.3 |

| Iatrogenic | 11 | 25 |

| Spontaneous | 10 | 22.7 |

| Total | 44 | 100 |

The commonest sites of leak included the lateral lamella of cribriform plate followed by the posterior ethmoid, sphenoid sinus, and the horizontal lamella of cribriform plate and frontal sinus Table 2.

Table 2.

Showing the sites of CSF leakage

| Variables | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral lamella of cribriform plate | 26 | 59.1 |

| posterior ethmoid | 6 | 13.6 |

| Sphenoid sinus | 6 | 13.6 |

| Horizontal lamella of cribriform plate | 4 | 9.1 |

| Frontal sinus | 2 | 4.5 |

| Total | 44 | 100.0 |

In our study, connective tissue grafts taken included Fascia lata, temporalis fascia, abdominal fat and septal bone graft as well as cartilage. The substances or grafts used in repair are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Showing the Grafts or tissues and materials used in CSF rhinorrhea repair

| Variables | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Fat, fascia lata, Fibrin glue | 20 | 45.5 |

| Fat, fascia lata, nasal mucosa, fibrin glue | 20 | 45.5 |

| Cartilage, fascia lata, fibrin glue | 4 | 9.1 |

| Total | 44 | 100.0 |

In our study, the success rate on endoscopic repair was 88.6%, similarly, only 5 (11.4%) patients were presented with leak following endoscopically repaired CSF rhinorrhea. The success rate and distribution of the leakage is shown in Table 4. In our study only two patients developed meningitis that was managed successfully. The follow up period extended up to 6 months.

Table 4.

Showing the success rate of Trans-nasal endoscopic CSF rhinorrhea repair

| Variables | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| No leakage | 39 | 88.6 |

| Leakage | 5 | 11.4 |

| Total | 44 | 100.0 |

As far as complications of the procedures are concerned, only 2 (4.5%) patients developed meningitis that too were managed conservatively and latter patients were discharged. Meningoceles were observed in one patient and this was from the cribriform plate. The complications related data is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Showing the complications observed following CSF rhinorrhea repair

| Variables | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| No complication | 42 | 95.5 |

| Meningitis | 2 | 4.5 |

| Total | 44 | 100.0 |

Discussion

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea refers to the abnormal leakage of CSF into the nasal cavity, often resulting from a breach in the dura and skull base following trauma or iatrogenic or spontaneous leakage. The observed etiologies in our study were in concordance with other studies and trauma was most commonly observed etiology of CSF leakage. The management of CSF rhinorrhea has evolved significantly over the years, with endoscopic repair emerging as a preferred approach. This discussion aims to explore the various aspects of endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea, including its advantages, techniques, outcomes, and potential complications. Endoscopic repair has emerged as a preferred approach for the management of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea due to its numerous advantages over traditional open surgical techniques. This minimally invasive procedure provides direct visualization of the defect, allowing for precise identification and repair without extensive tissue dissection. Additionally, endoscopic repair facilitates the concurrent management of associated pathologies, such as nasal polyps or sinusitis, leading to improved patient outcomes [9].

Studies have reported high success rates for endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea, ranging from 80 to 95% [10]. These success rates are indicative of the procedure’s efficacy in achieving closure of CSF leaks and preventing recurrent meningitis. Successful closure of the defect is typically associated with symptom resolution and improved quality of life for patients [11]. These studies findings were in concordance with the success rate of our study. In our study, 88.6% of the success rate was observed and that fall with-in the success range of other studies as well, thus making the endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea a preferred treatment modality. In the same way, the observed complication of the surgery was only meningitis that was also observed in just 2 (4.5%) of the patients and that too were managed conservatively and latter on discharged.

The technique employed for endoscopic repair depends on the size and location of the defect. Autologous grafts, including mucosal flaps and fat grafts, are commonly utilized due to their reliability and accessibility [12]. Synthetic materials, such as acellular dermal matrix or absorbable biomaterials, are alternative options when autologous tissue is inadequate or not feasible [13]. Sealants, such as fibrin glue, can be used as an adjunct to reinforce the repair and promote healing [14]. Similarly, the grafts and synthetic material used in our study were also in accordance to the studies conducted on CSF rhinorrhea repair and standard protocol of graft taken and grafted were followed. In our study, Fat, fascia lata, fibrin glue and nasal mucosa were most commonly used grafts in our study patients.

While endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea is generally safe, it is important to consider potential complications. Although rare, postoperative meningitis, recurrent leaks, and intracranial complications such as pneumocephalus or meningitis may occur [11, 15]. These complications underscore the need for close postoperative monitoring and appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis to minimize the risk of infection and ensure optimal outcomes. As reported in other studies, meningitis was the commonly observed complication that developed in 4.5% of the patients and patients were managed as per standard protocol of meningitis management. Similarly, the success of the procedure was documented in the form of leakage and no leakage, in our study leakage was observed in only 11.4% of the patients.

In conclusion, endoscopic repair has revolutionized the management of CSF rhinorrhea by offering several advantages over traditional open surgical techniques. The minimally invasive nature of the procedure, coupled with direct visualization and concurrent management of associated pathologies, contributes to improved patient outcomes and satisfaction. High success rates have been reported, indicating the efficacy of the procedure in achieving closure of CSF leaks and preventing complications. However, vigilance in postoperative care and awareness of potential complications are essential for optimizing outcomes.

Conclusion

Accurate localization of site of leakage using high resolution computed tomography and magnetic resonance image confirming the site of leakage by intrathecal fluorescence dye along with multilayer closure of dural defect and postoperative lumbar drain appears to be essential for successful endoscopic repair of CSF rhinorrhea. In our study cribriform plate area was commonly observed area of CSF leak. In our study, the success rate was 88.6% and low complication rate 4.5%.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Research Involving Human Participants and/ or Animals

Humans were involved in this particular research.

Informed Consent

All patients were informed about the nature of the project and their verbally and written consent was taken for participation in our study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bhalodiya N, Joseph S. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: endoscopic repair based on a combined diagnostic approach. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (April–June. 2009;61:120–126. doi: 10.1007/s12070-009-0049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tohge R, Takahashi M. Cerebrospinal fluid Rhinorrhea and subsequent bacterial meningitis due to an atypical clival fracture. Intern Med. 2017;56:1911–1914. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.8186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchiano E, Carniol E, Guzman D, Raikundalia M, Baredes S, Eloy J. An analysis of patients treated for Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea in the United States from 2002 to 2010. J Neurol Surg B. 2017;78:18–23. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virk JS, Elmiyeh B, Saleh HA. Endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: the charing cross experience. JNeurolSurg B Skull Base. 2013;74(2):61–67. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le C, Strong EB, Luu Q. Management of Anterior Skull Base Cerebrospinal fluid leaks. J Neurol Surg B. 2016;77:404–411. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin C, Capoccioni G, Garcia R, Restrepo E. Surgical challenge: endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid leak. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:549. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh R, Hazarika P, Nayak D, Balakrishnan R, Hazarika M, Singh A. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fl uid rhinorrhea – Manipal experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (January–March. 2009;61:14–18. doi: 10.1007/s12070-009-0026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gang Kong Y, Deng Y, Wang Y. Transnasal endoscopic repair of Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea: an analysis of 22 cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (August. 2013;65(Suppl 2):S409–S414. doi: 10.1007/s12070-013-0628-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psaltis AJ, Schlosser RJ, Banks CA, Yawn J, Soler ZM. A systematic review of the endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(2):196–203. doi: 10.1177/0194599812436574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattos JL, Schlosser RJ. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(4):857–872. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlosser RJ. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(6):473–477. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey RJ, Goddard JC, Wise SK, Schlosser RJ. Effects of endoscopic sinus surgery and delivery device on cadaver sinus irrigation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(3 Suppl 3):S38–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karligkiotis A, Demeyere N, Bechter K, et al. Long-term results of endoscopic repair of skull base defects with acellular dermal matrix. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(2):364–370. doi: 10.1002/lary.25401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhury N, Ayache D. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: is a lumbar drain necessary? Laryngoscope. 2017;127(6):1351–1357. doi: 10.1002/lary.26334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schick B, Ibing R, Brors D. Complications in endoscopic sinus surgery: a retrospective study of 1150 patients. Laryngorhinootologie. 2012;91(4):247–253. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]