Abstract

Various clinico-pathological factors play role in the papilloma proliferation and pathogenesis of Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP). However, it is not known if they are directly responsible for malignant transformation of these papillomas or not. We did this study to elucidate any such association. The most recent debrided tissue of RRP in 20 patients was evaluated for p16 expression, VEGF estimation (tissue expression and serum levels), and tissue HPV DNA concentration. The final histopathology results were then correlated with these pathological factors and with clinical factors like duration of illness, age of onset of symptoms, extent of disease, etc. Squamous papilloma was seen in 60%, dysplasia in 25%, and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 15% of the patients. Positive immunostaining for p16 (staining in ≥70% of tumor cells) was seen only in one case, which was SCC. There was no statistically significant difference between p16 expression, tissue VEGF expression, serum VEGF levels, and tissue HPV DNA in any of the histological groups. The mean age of disease onset was significantly higher in patients with SCC (p = 0.03). A significantly higher number of patients with dysplasia had tracheobronchial involvement (p = 0.022). We concluded that no single pathological factor is solely responsible for development of malignancy in RRP, whereas clinical factors like tracheobronchial involvement and age of onset may contribute to development of dysplasia or carcinoma.

Keywords: p16, VEGF, HPV DNA, Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis

Introduction

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) is a disease of the upper aero-digestive tract, affecting children and young adults, caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). Both low risk (HPV 6 and 11) and high risk (HPV 16 and 18) HPV subtypes are associated with RRP. However, about 90% of the cases are caused by HPV 6 and 11 [1]. RRP has rare risk of malignant transformation to invasive squamous cell carcinoma which is < 1% in children and 3–7% in adults [1, 2]. The risk factors associated with this malignant transformation are HPV subtypes, age of onset of symptoms, smoking, previous radiotherapy, cytotoxic drug use, tracheobronchial involvement, and p53 gene mutation [1–3]. It is well-established that E6 and E7 oncoproteins in RRP inactivate p53 and Retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor genes, respectively. Inactivation of the Rb gene leads to overexpression of p16. The role of p16 as a surrogate marker for HPV is widely accepted in head and neck cancers, especially in oropharyngeal malignancies. Although the detection of HPV RNA by in-situ hybridisation technique is confirmatory to detect transcriptionally active virus in RRP, but the immunostaining of papillomatous tissue with p16 antibody has also been used occasionally with low specificity as a biomarker to detect HPV in RRP [3–6]. However, it is not known if there is any correlation between p16 expression and development of dysplasia or malignancy in RRP. Likewise, the role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in solid organ malignancies and their progression is well documented and forms the basis of anti-VEGF therapies in these tumors [7]. In RRP, vascular growth is essential for papilloma proliferation and squamous papillomas express high levels of VEGF. This forms the basis of anti-VEGF therapy like Bevacizumab in RRP as well [8]. But whether this higher VEGF expression leads to a dysplastic or malignant change in RRP is not completely understood. We conducted a pilot study to co-relate p16 immunoexpression, VEGF immunoexpression, serum VEGF levels, and HPV DNA concentration in patients with RRP with the development of dysplasia and invasive carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

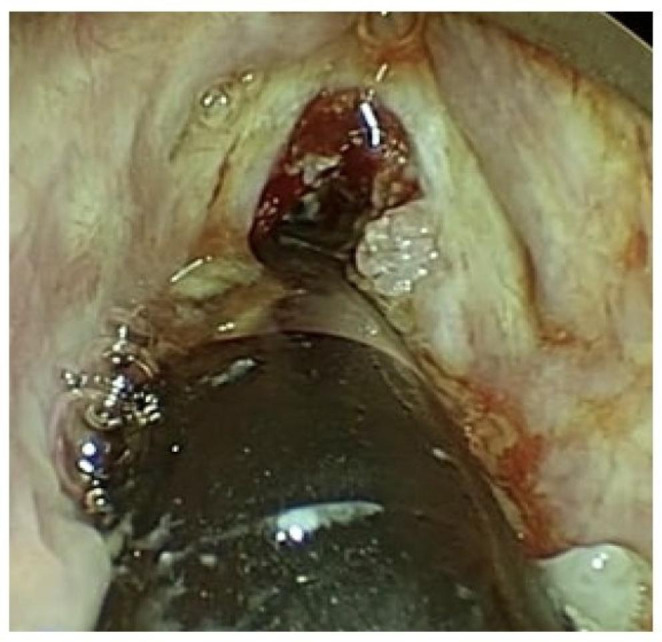

This was a retrospective cohort study done at a tertiary healthcare centre under a project sanctioned by our institute research committee after ethical clearance (Project code: A-465). The study group included cases of RRP treated surgically from November 2016 to November 2019. The elective surgeries were halted post 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic for 2 years and we did not include patients with RRP who underwent emergency surgery due to potential airway risk during this period. We could retrieve the analysable data of 20 out of 37 patients managed during the study period as the other 17 had one or more missing parameters (like age of onset of disease, duration of illness, number of surgeries performed, etc.). All patients underwent micro laryngeal surgery and debridement of papillomas either by cold instruments or by powered instruments like microdebrider or coblation (Fig. 1) under general anaesthesia. The most recent debrided tissue was evaluated for p16 expression, VEGF expression, and HPV DNA concentration. VEGF levels were also measured in the serum.

Fig. 1.

Laryngeal papillomas removed using coblation

Immunohistochemistry Staining Method for p16 Expression

Immunohistochemistry for p16 was performed on whole tissue sections as described previously [9]. Semiquantitative scoring was performed as follows: 0: completely negative; 1+: staining in 1–29% of tumor cells; 2+: staining in 30–49% of tumor cells; 3+: staining in 50–69% of tumor cells; and 4+: staining in ≥ 70% of tumor cells. Diffuse strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in ≥ 70% of the tumor cells i.e., 4 + was considered as positive [10].

VEGF Estimation Method

VEGF expression was assessed in respiratory papillomas using a semiquantitative scoring method for VEGF immunohistochemistry by an experienced pathologist blinded to patient outcome. The cytoplasmic staining in endothelial cells of blood vessels in the fibrovascular cores of the papillomas was considered as positive. During staining of each batch, appropriate positive and negative controls were used. The percentage of positively stained cells was evaluated (none = 0; 1 to 25% = 1, 26–50% = 2; >50% = 3) and the staining intensity was assessed (none = 0; weak = 1; moderate = 2; strong = 3). The percentage and intensity scores were added together to give a final immunoreactive score (IRS) of 0 to 6. IRS of 0, 1 to 4 and 5 to 6 were considered as no, weak, and strong expression, respectively. Additionally, 10 ml of venous blood samples were collected from patients and left to clot at room temperature to separate sera after centrifuging for 10 min at 3000 rotation per minute and stored at -70 ◦C until batch analysis. Serum VEGF-A evaluation was done using a commercially available ELISA assay.

Estimation of Tissue HPV DNA Concentration

Three to four 10 μm thick tissue sections were cut from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue blocks of patients under study. The DNA of each sample was extracted from these FFPE tissues. Promega Reliaprep FFPE gDNA Miniprep system- A2352 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) kit was used to extract the DNA following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of DNA present in extracted 35 µL of DNA suspension of each sample was evaluated by using Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermofisher). Blank was measured before the estimation of sample’s DNA concentration. The concentration of DNA yield was taken as ng/µL at absorbance 260 nm. The quality of the sample was assessed by the A260/A280 absorbance ratio of about 1.8. The extracted DNA of all the samples was stored at − 20 °C for further genotyping by PCR.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher Exact test was used to estimate any significant difference between p16 expression and VEGF expression of patients with or without dysplasia and carcinoma. Two tailed t- test was used to see any significant difference between tissue HPV DNA concentration and serum VEGF levels between different groups. Chi-square test was done to see any significant difference between dysplasia and carcinoma with laryngeal subsite or tracheobronchial involvement.

Results

The data of 20 patients (12 males and 8 females) was retrieved retrospectively. The age of patients included in the study ranged from 3 years to 60 years and the mean age of onset of disease was 14.7 years. A total of 15 patients had Juvenile-onset RRP (JORRP), that is, the onset of symptoms before 18 years of age, and 5 patients had Adult-onset RRP (AORRP). The average duration of illness from age of onset of symptoms till age at last presentation was 8.8 years. All patients had a history of birth by normal vaginal delivery and all had undergone multiple procedures for debridement, ranging from a minimum of one procedure to maximum of 173 procedures till the last presentation. Family history was significant in two patients who had siblings with a history of RRP, and one patient had a past history of papillary carcinoma thyroid for which she underwent total thyroidectomy.

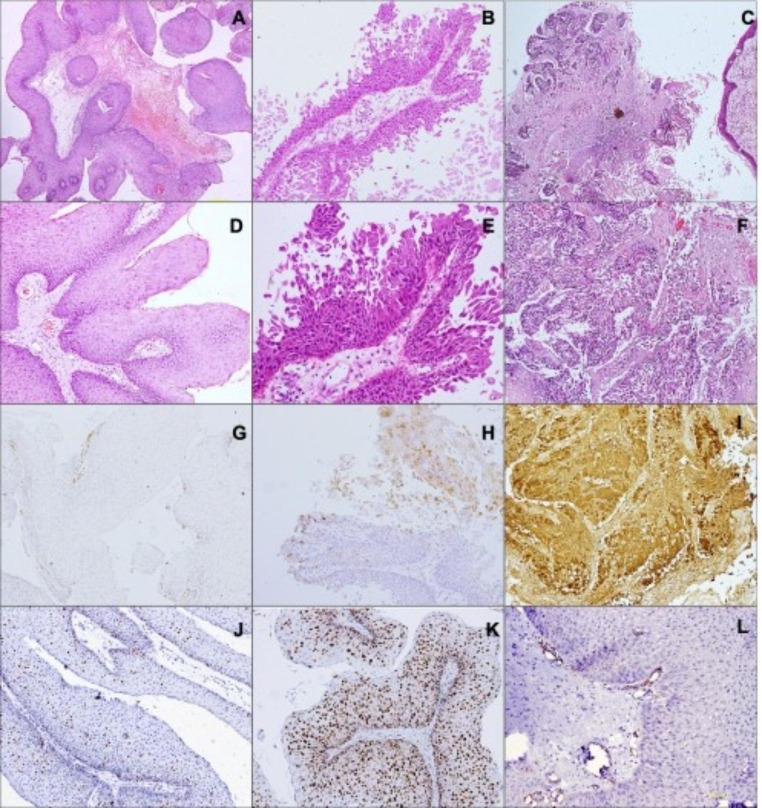

Out of the 20 patients, the final histopathology (Fig. 2) revealed squamous papilloma in 60% (12/20), dysplasia in 25% (5/20), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 15% (3/20) of the patients. Table 1 shows demographic details in each of these groups.

Fig. 2.

Low magnification (A, B, C; HE, 100x) and high magnification (D, E, F; HE, 200x) of cases of squamous papilloma (A, D) papilloma with dysplasia (B, E) and squamous cell carcinoma (C, F) with corresponding p16 (G, H, I; IHC, 200x) and Ki-67 (J, K; IHC, 200x). Squamous papilloma with VEGF staining in endothelial cells lining blood vessels (L; IHC, 200x)

Table 1.

Demographic details of patients in all three histological groups

| Histopathology | Number of patients (F – Females, M – Males) | Mean Age (years) |

Mean Age of onset of disease (years) | Number of patients with JORRP and AORRP* | Mean duration of symptoms (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squamous papilloma | 12 (5 F, 7 M) | 17.8 | 11.5 | 10 JORRP and 2 AORRP | 6.2 |

| Squamous papilloma with dysplasia | 5 (1 F, 4 M) | 21.8 | 10.6 | 4 JORRP and 1 AORRP | 11.2 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3 (2 F, 1 M) | 49 | 34 | 1 JORPP and 2 AORRP | 15.16 |

*JORRP – Juvenile onset Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (age < 18 years), AORRP – Adult onset Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (age = or > 18 years)

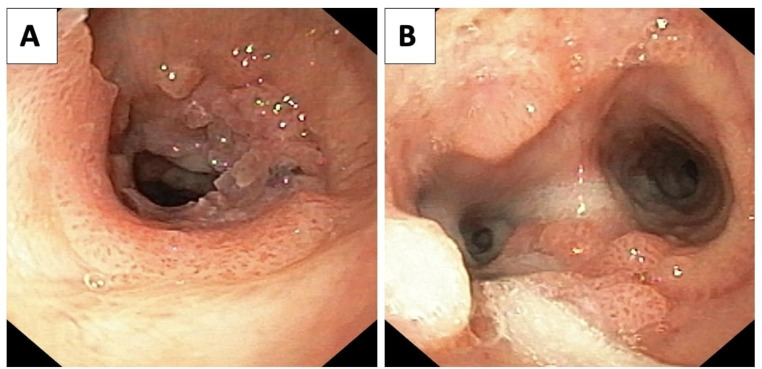

Positive immunostaining (staining in ≥ 70% of tumor cells) for p16 was seen only in one case (5%), which was SCC. None of the squamous papillomas, with or without dysplasia, were positive for p16. There was no statistically significant difference between p16 expression of patients with squamous papilloma vs. those with SCC (p = 0.20). p16 staining in squamous papillomas was restricted to the basal to middle thirds of the epithelium, while it was seen in the entire thickness of the epithelium in most of the papillomas with dysplasia and SCC. There was no statistically significant difference between tissue VEGF expression, serum VEGF levels, and tissue HPV DNA concentrations in these histological groups as seen in Table 2. However, the mean age of disease onset was significantly higher in patients with SCC as compared to those with squamous papilloma (p = 0.03) and a significantly higher number of patients with dysplasia had tracheobronchial involvement (Fig. 3) as compared to those without dysplasia (p = 0.022).

Table 2.

Comparison of various parameters assessed in all three groups

| PARAMETER ASSESSED | Papilloma | Dysplasia | Invasive carcinoma | Comparison category | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue p 16 expression* (n = number of patients) | Positive (p16 score: number of patients) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1+: 1 case) | Papilloma vs. Carcinoma | 0.2 |

| Negative (p16 score: number of patients) |

12 (0: 3 cases 1+: 9 cases) |

5 (1+: 5 cases) | 2 (1+: 1 case 2+: 1 case) | |||

| Tissue VEGF expression** (n) | Positive | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | |

| Negative (score: number of patients) | 12 (0: 5, 1: 3, 2: 2, 3: 2) | 5 (1: 3, 2: 1, 3: 1) | 3 (1: 3) | |||

| Serum VEGF levels (pg/ml) | 117.16 | 167.5 | 179.44 | Papilloma vs. Dysplasia | 0.34 | |

| Papilloma vs. Carcinoma | 0.33 | |||||

| HPV DNA concentration (ng/µL) | 240.8 | 142.28 | 149.4 | Papilloma vs. Dysplasia | 0.23 | |

| Papilloma vs. Carcinoma | 0.45 | |||||

| Laryngeal subsites involved (n) | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | Papilloma vs. Dysplasia | 0.58 |

| > 2 | 8 | 4 | 2 | Papilloma vs. Carcinoma | 1 | |

| Tracheobronchial involvement (n) | Yes | 1 | 3 | 0 | Papilloma vs. Dysplasia | 0.022 |

| No | 11 | 2 | 3 | Papilloma vs. Carcinoma | 1 | |

| Mean age of onset of disease (years) | 11.5 | 10.6 | 34 | Papilloma vs. Dysplasia | 0.55 | |

| Papilloma vs. Carcinoma | 0.03 | |||||

| Type of HPV (n) | High Risk (HPV 16) | 5 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Low risk (HPV 6 and 11) | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Both high risk and low risk | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| None detected | 5 | 3 | 1 | |||

* p16 immunostaining − 0: completely negative; 1+: staining in 1–29% of tumor cells; 2+: staining in 30–49% of tumor cells; 3+: staining in 50–69% of tumor cells; and 4+: staining in ≥ 70% of tumor cells (considered positive)

** Immunoreactive score (as described in methodology) – 0: No expression; 1–4: Weak expression; 5–6: Strong expression (considered positive)

Fig. 3.

A: Papillomas involving Trachea, B: Involvement up to carina

There was no association of development of carcinoma or dysplasia with gender, duration of the illness, and the number of surgeries performed. There was no significant difference between tissue VEGF expression, serum VEGF levels, and tissue HPV DNA concentrations when compared between JORRP vs. AORRP, tracheobronchial tree involvement, or type of HPV (high risk vs. low risk). However, the serum VEGF levels were significantly higher in those with more than two laryngeal subsites involvement (p = 0.011) as seen in Table 3. The p16 and VEGF expression was not different with respect to laryngeal subsite involvement.

Table 3.

Comparison of additional parameters assessed

| PARAMETER ASSESSED (Comparison category) |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p16 expression | HPV DNA concentration | Serum VEGF levels | |

| Age of onset (JORRP vs. AORRP) | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.64 |

| Laryngeal subsite involvement (2 vs. > 2 sites involvement) | 1 | 0.55 | 0.011 |

| Tracheobronchial involvement (Yes vs. No) | 1 | 0.84 | 0.68 |

| Type of HPV (High risk vs. Low risk) | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.56 |

HPV DNA was detected in 55% (11/20) of the RRP tissue specimens examined in our study. Only high-risk HPV (HPV 16) was seen in six patients, only low risk HPV (HPV 6 and 11) was seen in one patient, and both high risk (HPV 16) and low risk HPV (HPV 6 and 11) were seen in four patients. None of the patients had HPV 18. One patient with dysplasia had low risk HPV and one had both low risk and high risk HPV DNA. In three patients with dysplasia, it was not detected. The first patient with SCC with p16 immunopositivity showed the presence of high-risk HPV (HPV 16). The second patient with SCC without p16 immunopositivity showed both high risk and low risk HPV and the third patient with SCC without p16 immunopositivity did not show any HPV type. The mean HPV DNA concentration was less in dysplasia (142.28 ng/µL) and invasive carcinoma group (149.4 ng/µL) as compared to that papilloma group (240.8 ng/µL), although the difference was not statistically significant as seen in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference between tissue p16 expression, VEGF expression, serum VEGF levels, and HPV DNA concentration between high risk and low risk HPV group (Table 3).

Discussion

RRP is considered a benign neoplasm with rare risk of malignant transformation into SCC. However, the exact mechanism for this transformation still remains unclear. The age of onset of disease is a strong predictor of malignant transformation with older age of disease onset in AORRP and younger age of disease onset in JORPP having increased risk of dysplasia or carcinoma [6, 7]. We also found that there was a statistically significant difference between age of onset of disease in carcinoma vs. benign group. However, similar results were not seen in terms of dysplasia.

In a large cohort study by Omland et al. to examine the HPV genotype profile and to determine whether RRP is associated with the development of laryngeal neoplasia, it was found that 17.6% of the patients had moderate to severe dysplasia with increased incidence in men. In our study, dysplasia was seen in 25% of the patients. In contrast to our study, which showed invasive carcinoma in 15% of the patients, the squamous cell carcinoma in the larynx in this study was found in only 2.7% patients [8]. The reason for higher incidence of malignant transformation in our study, despite the small sample size, could be because this study was done at an apex institute of the country where we get a lot of referrals for chronic illnesses after failed treatment in other parts of the country. RRP is a similar kind of illness which requires repeated medical & surgical interventions which is not done at many hospitals and patients present to us at a later stage of the disease when development of dysplasia or carcinoma has already occurred.

p16 overexpression is seen in squamous dysplasia of cervix and head-neck pathologies [11]. But its role in squamous dysplasia of RRP is not well-established. Diffuse strong p16 staining seen in patients with transcriptionally active high-risk HPV, while it is absent or is focal and of weak intensity in those with low-risk HPV [12]. Pham et al. did a study to assess the role of p16INK4A on tumor progression in RRP. The immunohistochemistry of p16INK4A was performed on biopsies of recurrent squamous papillomas and invasive lesions in nine patients. They found that 45% of the biopsies with papilloma and 60% of the biopsies with high grade dysplasia/carcinoma in-situ/invasive carcinoma expressed p16. However, this was neither predictive of invasive transformation nor did it correlated with the disease severity [13]. Likewise, in a study by Donne et al., p16 immunostaining was negative in all children (n = 48) with RRP while expression of the RNA of HPV genes E6 and E7 with a chromogenic in situ hybridization was found to be a potential biomarker for aggressiveness of JORRP [3]. In our study, none of the patients with papilloma or dysplasia showed positive p16 immunostaining, and only one patient out of three with invasive carcinoma showed positive staining for p16 which was accompanied by detection of high-risk HPV. Another patient with invasive carcinoma but without p16 immunopositivity also showed presence of both high risk and low risk HPV. This indicates that high-risk HPV may be one of the many contributing factors for malignant transformation of squamous papillomas in RRP as evident in the literature which shows that HPV 16 and HPV 18 along with HPV 11 are more frequently associated with malignant transformation than HPV 6 [3–5]. Therefore, we cannot attribute sole overexpression of p16 or only presence of high risk HPV DNA to malignant transformation because as stated earlier other factors like overexpression of p53, suppression of p21, age of onset, etc. also contribute to malignant transformation [14].

The viral genome can replicate either in an episomal manner or via integrating to the host genome. The latter causes strong expression of E6 and E7 viral proteins and it is only in these cases where carcinogenic transformation occurs [2, 3, 15, 16].We detected HPV DNA in 55% of the specimens and measured its concentration. High risk HPV DNA was seen in seven patients with papilloma, only one patient with dysplasia and two patients with SCC. However, it is well known now that the HPV DNA detection does not differentiate between episomal DNA and integrated DNA. It is HPV RNA detection which gives insights on transcriptionally active HPV inside the cell. In RRP, HPV negativity is associated with higher risk of malignant potential [8, 17]. We also found that the mean HPV DNA concentration was less in dysplasia and invasive carcinoma group as compared to that of papilloma group but the result was not significant. However, the non-detection of HPV DNA may also be false negative due to inadequate sample, low sensitivity of the detection method, and the presence of unidentified HPV types [8]. This can be checked by detecting the transcriptionally active virus in the tissue using HPV RNA in-situ hybridization technique which was not done in our study due to logistic issues and is one of the limitations of our study. The cut-off value of HPV concentration below which the risk of dysplasia or carcinoma increases could not be estimated because of two reasons. Firstly, there was no comparative data in the literature to compare our results and secondly, due to small sample size.

VEGF plays an important role in the pathogenesis of RRP and it forms the basis of anti-VEGF therapy like Bevacizumab [18]. All of VEGF’s actions are mediated by interaction with two high-affinity receptors, VEGF-A receptor-I (VEGFR-l) and VEGF-A receptor-2 (VEGFR-2). A significant expression of VEGF-A mRNA and its receptors is seen in the papilloma tissue bed, which plays an important role in vascular stroma formation and development of papilloma [19]. Vargas et al. showed that VEGF-A is strongly expressed in the epithelium of squamous papillomas in RRP and VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 mRNAs are strongly expressed by underlying vascular endothelial cells [20]. A study by Verma et al. also showed that systemic and tissue expression of VEGF-A was significantly higher among cases of RRP than controls [21]. In our study, we measured VEGF levels in serum as well as tissue VEGF expression in cytoplasm of endothelium of blood vessels from core of papilloma. We found no significant difference between serum levels or tissue expression of VEGF of patients with simple papillomas and those with dysplasia or invasive carcinoma. But serum levels were significantly higher in patients with more than two laryngeal subsite involvement. This may indicate that VEGF expression is just an indicator of more vascular proliferation and play role in local spread of papillomas, but its role in malignant transformation of squamous papillomas of RRP needs further large sample studies. The pulmonary involvement in RRP is associated with progressive disease and higher risk of malignancy [22, 23]. We also found that a significantly more number of patients with dysplasia had tracheobronchial involvement than those without dysplasia.

Although our study was limited by small sample size, lack of control specimens, and lack of HPV RNA detection, but it shows that a sole molecular pathology is not responsible for malignant transformation and it may be interplay of multiple factors like age of onset, duration of symptoms, pulmonary involvement, etc. which ultimately lead to development of invasive carcinoma in RRP.

Conclusion

There is no difference between tissue p16 immunoexpression, VEGF expression, serum VEGF levels, and tissue HPV DNA concentration of those with papilloma and those with dysplasia or malignancy in RRP and none of these factors may be solely responsible for malignant transformation. Tracheobronchial involvement and age of onset of disease may contribute to the development of dysplasia or carcinoma. Further studies with larger sample size are required to validate the results.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Smile Kajal and Aanchal Kakkar be considered as first authors.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fortes HR, von Ranke FM, Escuissato DL, et al. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: a state-of-the-art review. Respir Med. 2017;126:116–121. doi: 10.1016/J.RMED.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fusconi M, Grasso M, Greco A, Gallo A, Campo F, Remacle M, Turchetta R, Pagliuca G, DE Vincentiis M. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis by HPV: review of the literature and update on the use of cidofovir. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34(6):375–381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donne AJ, Hampson L, Homer JJ, Hampson IN. The role of HPV type in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/J.IJPORL.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin HW, Richmon JD, Emerick KS, et al. Malignant transformation of a highly aggressive human papillomavirus type 11-associated recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(4):291–296. doi: 10.1016/J.AMJOTO.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiatrak BJ, Wiatrak DW, Broker TR, Lewis L. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: a longitudinal study comparing severity associated with human papilloma viral types 6 and 11 and other risk factors in a large pediatric population. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(11 Pt 2 Suppl 104):1–23. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.000148224.83491.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karatayli-Ozgursoy S, Bishop JA, Hillel A, Akst L, Best SRA. Risk factors for dysplasia in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in an adult and pediatric population. Annals of Otology Rhinology and Laryngology. 2016;125(3):235–241. doi: 10.1177/0003489415608196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitsumoto GL, Bernardi F, del Villa C, Mello LL, Pozzan B (2018) Juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis with pulmonary involvement and carcinomatous transformation. Autops Case Rep 8(3). 10.4322/ACR.2018.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Omland T, Lie KA, Akre H et al (2014) Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: HPV genotypes and risk of high-grade laryngeal neoplasia. PLoS ONE 9(6). 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0099114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Antony VM, Kakkar A, Sikka K, et al. p16 immunoexpression in sinonasal and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinomas: a potential pitfall in ruling out HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma. Histopathology. 2020;77(6):989–993. doi: 10.1111/HIS.14212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis JS, Beadle B, Bishop JA, et al. Human papillomavirus testing in Head and Neck Carcinomas: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(5):559–597. doi: 10.5858/ARPA.2017-0286-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JL, Zheng BY, Li XD, Ångström T, Lindström MS, Wallin KL. Predictive significance of the alterations of p16INK4A, p14ARF, p53, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in the progression of cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(7):2407–2414. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirghani H, Amen F, Moreau F, et al. Human papilloma virus testing in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: what the clinician should know. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/J.ORALONCOLOGY.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pham TT, Ongkeko WM, An Y, Yi ES. Protein expression of the tumor suppressors p16INK4A and p53 and disease progression in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):253–257. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000248241.95357.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lele SM, Pou AM, Ventura K, Gatalica Z, Payne D. Molecular events in the progression of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis to carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(10):1184–1188. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-1184-MEITPO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reidy PM, Dedo HH, Rabah R, et al. Integration of human papillomavirus type 11 in recurrent respiratory papilloma-associated cancer. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(11):1906–1909. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000147918.81733.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rady PL, Schnadig VJ, Weiss RL, Hughes TK, Tyring SK. Malignant transformation of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis associated with integrated human papillomavirus type 11 DNA and mutation of p53. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(5):735–740. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibeko SR, Seedat RY. Adult-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis at a south african Referral Hospital. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 3):5188–5193. doi: 10.1007/s12070-022-03110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enrique OH, Eloy SH, Adrian TP, Perla V (2021) Systemic bevacizumab as adjuvant therapy for recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in children: a series of three pediatric cases and literature review. Am J Otolaryngol 42(5). 10.1016/J.AMJOTO.2021.103126 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Doyle-Lloyd DJ, Gianoli GJ. Laryngeal papillomatosis: clinical, histopathologic and molecular studies. Laryngoscope. 1987;97(6):551–554. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vargas SO, Healy GB, Rahbar R, et al. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor-A in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114(4):289–295. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma H, Chandran A, Shaktivel P, et al. The serum and tissue expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;146:110737. doi: 10.1016/J.IJPORL.2021.110737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gélinas JF, Manoukian J, Côté A. Lung involvement in juvenile onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(4):433–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitsumoto GL, Bernardi FDC, Paes JF, Villa LL, Mello B, Pozzan G. Juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis with pulmonary involvement and carcinomatous transformation. Autops Case Rep. 2018;8(3):e2018035. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]