Abstract

Background

Laryngeal tuberculosis (TB) is the commonest granulomatous condition found in the larynx and may be primary or secondary. With the recrudescence of tuberculosis and development of multidrug resistance, the classical disease trend of laryngeal tuberculosis is changing its manifestations. The aim of our study is to describe the various patterns of presentations of laryngeal tuberculosis in the current era and consequently its changing management protocols.

Results

In this retrospective study, out of 890 patients who visited our voice and swallowing clinic in our study period, 10 were diagnosed as granulomatous conditions [1.1%] and 3 of these were confirmed cases of tuberculosis involving the larynx [0.3%]. Secondary laryngeal TB was found in 1 of our patients with a “dirty larynx picture”. Primary laryngeal TB was seen in 2 patients, one patient presented with a unilateral congested vocal fold and the other with bilateral striking zone leukoplakia.

Conclusion

The clinical pattern of presentation of laryngeal tuberculosis has changed over the years. None of the patients of primary or secondary laryngeal tuberculosis had the classical constitutional symptoms of tuberculosis. In patients with laryngeal tuberculosis along with routine TB workup, surgical excision with histopathological testing is essential for accurate diagnosis in primary laryngeal TB and the “dirty larynx” picture aids in the diagnosis of secondary laryngeal TB. The healing and vocal outcomes are good in both primary and secondary laryngeal TB, once the appropriate antitubercular regimen has been started.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Primary Laryngeal Tuberculosis, Secondary Laryngeal Tuberculosis, ESR, Dirty Larynx

Introduction

Laryngeal tuberculosis (TB) is uncommon and may be divided into two groups: primary (with no pulmonary involvement) and secondary (with pulmonary involvement) [1]. The mode of transmission of infection in secondary laryngeal TB is usually by bronchogenic spread from the lungs and occasionally by a hematogenous or lymphatic route [2]. Primary laryngeal TB is a result of direct seeding of the tubercle bacilli on the laryngeal structures probably inhaled directly or rarely via a hematogenous spread from an unknown primary site in the body [3–7].

In the pre antibiotic era, secondary laryngeal tuberculosis accounted for 15–40% of all the pulmonary tuberculosis cases [3, 8] with classical laryngeal features of turban epiglottis, involvement of posterior glottic area and a mouse nibbled appearance of the mucosa [3, 9, 10]. With the routine use of effective antitubercular medications, the incidence of laryngeal tuberculosis had decreased to less than 1% [5]. However, with the recrudescence of TB and development of multidrug resistant tuberculosis, the classical disease trend of laryngeal tuberculosis is changing its manifestations [9].

The aim of our study is to describe the various patterns of presentation of laryngeal tuberculosis in the current era and consequently its changing management protocols.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective observational study performed at the voice and swallowing center of a tertiary care hospital from August 2021 to July 2022. The medical records accessed were the history sheets, stroboscopy reports, haematology and radiology reports, microbiology reports, operative notes and histopathology slides of all patients diagnosed with granulomatous voice disorders.

Results

Out of 890 patients who visited our voice and swallowing clinic in our study period, 10 were diagnosed as granulomatous conditions [1.1%] and 3 of these were confirmed cases of tuberculosis involving the larynx [0.3%]. Secondary laryngeal TB was found in 1 of our patients and 2 had primary laryngeal TB. Of the remaining 7 granulomatous conditions we had a total of 1 Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA or Wegener’s), 5 laryngeal candidiasis and 1 sarcoidosis. The 3 laryngeal TB cases are described here in brief.

Case 1

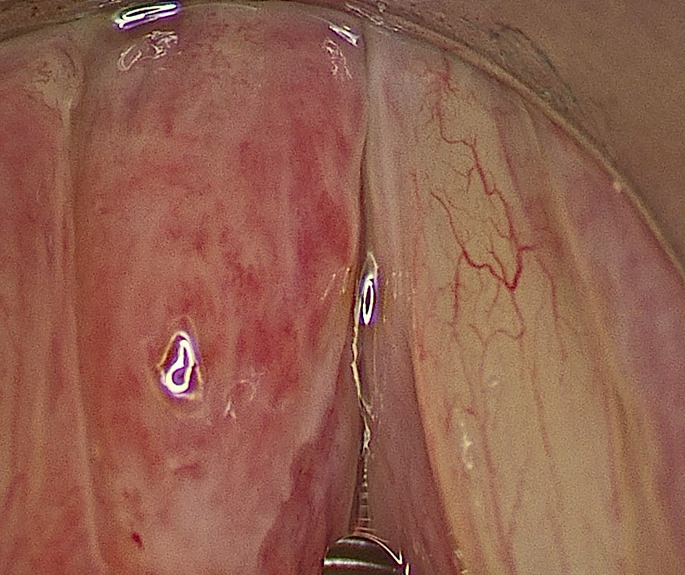

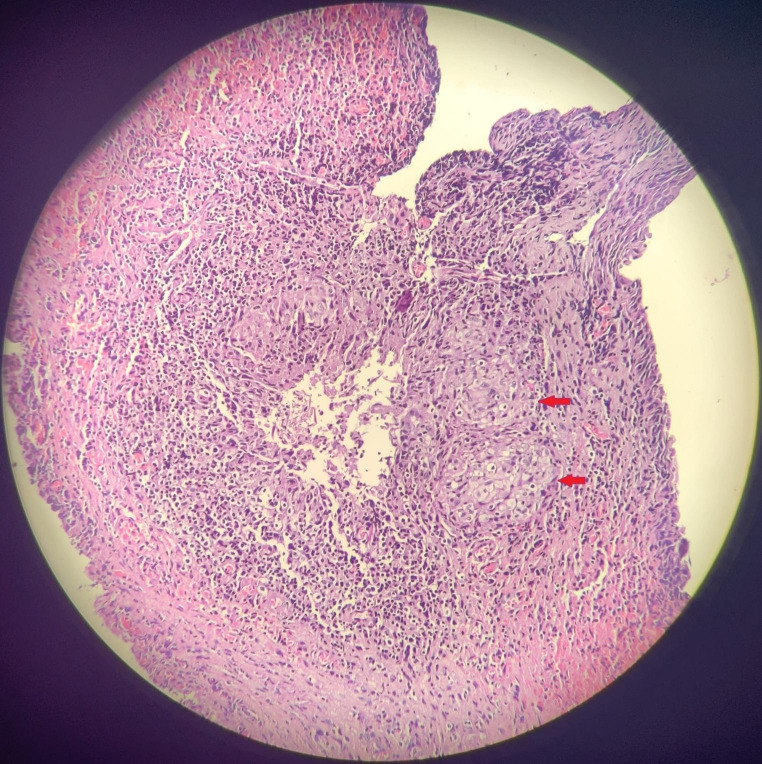

A 58-year-old chemistry teacher, taking 5–6 lectures of 1 h duration from the past 10–15 years, presented to us with a history of voice change since 2 months. On stroboscopy, he had a left congested vocal fold [Fig. 1] with a marked reduction in the mucosal wave amplitude. Narrow band imaging revealed a leash of meandering vessels with no intraepithelial papillary capillary loop pattern (IPCL pattern). Tuberculosis was considered as one of the differential diagnoses in this patient since unilateral congested vocal fold is one of the presenting signs of laryngeal tuberculosis seen in our clinic since the last decade. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 10, chest x-ray was normal, and 3 consecutive sputum samples were negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), indicating an absence of pulmonary tuberculosis. An incisional biopsy was performed away from the medial vibrating edge of this lesion using an acublade carbon di-oxide laser. His frozen report revealed an inflammatory / granulomatous lesion and the final histopathology revealed minimally necrotising granulomas with dense inflammation [Fig. 2] with no AFB seen on zeihl – neelson (Z-N) staining and no fungal hyphae seen.

Fig. 1.

- Intra-operative image showing a left congested vocal fold

Fig. 2.

- Histopathology [Hematoxylin – Eosin stain, magnification 40x] revealing necrotising caseating epithelioid granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate [ Red arrows]

Part of the excised tissue had been sent for Gene Xpert, which was positive and Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) Bactec culture (Becton Dickinson) for TB isolated mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. This patient was started on antitubercular regimen [AKT] as advised by the pulmonologist.

On the 4-month post operative stroboscopic evaluation, a well healed left vocal fold with normal amplitude was observed and the patient found his voice near normal.

Case 2

A 48-year-old female patient presented with a history of hoarseness of voice, which had been previously conservatively treated for 3 years. Her stroboscopy revealed, bilateral leukoplakia of the vocal folds [Fig. 3] for which an empirical treatment for fungal candidiasis was given. However, there was no improvement, following which, her TB workup was advised. Her ESR was normal, 3 consecutive morning sputum samples tested for AFB were negative and her chest x-ray was unremarkable. Thus, a surgical excision of both the leukoplakic lesions was performed. The histopathology report revealed squamous hyperplasia and her fungal culture was negative.

Fig. 3.

- Flexible videolaryngoscopic image showing bilateral vocal fold leukoplakia at the striking zone

The patient had a slow vocal recovery over a period of 4–5 months. However, following this recovery, within 2 months, she developed a recurrence of bilateral vocal fold lesions. Her case was discussed with multiple international laryngologists, who recommended to rule out TB by MGIT Bactec culture and to take a rheumatologist’s opinion for autoimmune diseases and a gastroenterologist’s opinion for ruling out Crohn’s disease. Following these evaluations, her sputum MGIT bactec culture isolated mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and her repeat ESR was 100. Following an anti-tubercular regimen, she improved dramatically.

Case 3

A 31-year-old male patient with a history of voice change since 2 months had been treated for fungal laryngitis and then referred to us as he did not respond to the antifungals.

On stroboscopy, he had a small anterior glottic web with congestion of bilateral vocal folds and slough noted over the entire larynx, including the infraglottis, giving a “dirty larynx” picture [as described by the first author]. [Figure 4]. His 3 sputum samples were positive for AFB, ESR was 17 and CT chest revealed focal pleural thickening with calcific foci in the right lower lobe and small nodules in left lower lobe with bronchiectasis changes.

Fig. 4.

- Flexible videolaryngoscopic image showing white patches [ slough like appearance] over the entire larynx, including the infraglottis appearing as a “dirty larynx” picture

He was diagnosed to have secondary laryngeal tuberculosis and referred to the pulmonologist to start antitubercular regimen to which he has responded well.

Discussion

Laryngeal tuberculosis is the most common granulomatous disease of the larynx [1–3, 11]. The other common differential diagnoses to be considered in the presence of granulomatous lesions of the larynx include GPA, sarcoidosis and fungal infections [1, 12, 13]. In GPA or Wegener’s granulomatosis, initial granulomatous inflammation at the subglottis leads to circumferential scarring and narrowing of the airway [16%] [14] as was seen in our patient. The upper respiratory tract is affected in 95% of these patients [14, 15]. Localized forms in the head and neck area are not exceptional [14, 16]. The distinctive histopathology features are necrosis, granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis. In sarcoidosis of the larynx, mucosal alterations including erythema, edema, punctate nodules and mass lesions are seen [17]. The epiglottis is the most frequently affected area, but any portion of the larynx may be involved [17]. Histopathologically, these granulomas are usually discrete, non-caseating with occasional presence of asteroid and Schaumann bodies [13]. Our patient of laryngeal sarcoidosis presented as an irregular granulomatous lesion of one vocal fold. Laryngeal involvement by fungal infections, most commonly by candidiasis, appears as cheesy white plaques on the vocal fold and larynx with surrounding congestion, as was seen in all 5 cases of ours. The diagnosis is usually confirmed with the presence of hyphae in KOH mount and the type of fungus is confirmed with fungal culture. Other rare granulomatous lesions include actinomycosis, blastomycosis, syphilis, SLE and amyloid [1, 12, 13].

The histopathology of tuberculosis is classically seen as caseating granulomas with a central caseous necrosis in the subepithelial stroma, surrounded by epithelioid macrophages, Langhans-type giant cells, and lymphocytes [13, 18]. As the clinical pattern of presentation of laryngeal tuberculosis has changed over the years, it is important to have a high index of clinical suspicion especially in primary laryngeal tuberculosis so as to take the decision to operate and send the specimen for histopathology and MGIT Bactec culture for early and accurate diagnosis.

Formerly, laryngeal TB involvement was always associated with advanced pulmonary infection [9] and the symptoms were similar to those in the case of pulmonary tuberculosis and involved mainly the posterior portion of the larynx [3]. However, in those cases with hematogenous or lymphatic spread, the spread was quick with predominant laryngeal symptoms such as dysphonia and odynophagia [3, 19], and the lesions were frequently seen in the epiglottis and anterior larynx and sometimes, in the pharynx, soft palate and tonsils [3]. Although secondary laryngeal tuberculosis through bronchogenic spread predominated in the past, incidence of primary laryngeal cases without pulmonary involvement is on the rise today [2, 3, 20].

In a study done by Ponni et al. in 2019 in India, out of 48 cases with laryngeal tuberculosis, 36 patients were diagnosed with primary laryngeal tuberculosis of which 22 atypical cases were described with features like acute epiglottitis in 8 cases, 10 mimicking laryngeal malignancy and 4 with polypoid lesions [10]. In another Indian study published in 2019 by Grover et al., 54 laryngeal tuberculosis cases of which 51 were secondary were described as granulomatous (50%), ulcerative (28%), hyperaemic and hypertrophic (17%) and papillomatous in 6% [19]. Swain et al. have published their experience in 2018 with 11 cases of primary laryngeal TB seen over 5 years. They have described all these cases as mimicking laryngeal malignancy [12].

In a study done by Shin et al. from Korea, in a total of 22 laryngeal tuberculosis cases, 7 had active pulmonary tuberculosis, and 9 were proven to have normal lung status. The remaining 6 had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis which had been diagnosed to be inactive. The patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis showed multiple ulcerative lesions. The patients with normal lung status showed nonspecific, polypoid, and single lesions [6].

The diagnosis of laryngeal tuberculosis in the past was based on presence of features of active pulmonary tuberculosis with constitutional symptoms and identification of characteristic lesion of laryngeal tuberculosis, such as, monocorditis, laryngeal peri-chondritis, interarytenoid mamillations, turban epiglottis, posterior glottic ulcers (mouse nibbled ulcers), granulations, edema and thickening of aryepiglottic folds [10]. The changing patterns of presentation of laryngeal tuberculosis was observed in our cases with the 2 primary laryngeal tuberculosis patients presenting with a unilateral congested vocal fold and bilateral leukoplakia respectively. Huon et al. also described a similar finding in their case report in Taiwan, where the patient had irregular thickening of right vocal cord with congestion [18]. Guan et al. in their study in Malaysia concluded that primary laryngeal tuberculosis must be considered as a differential diagnosis in a patient with unilateral irregular vocal fold lesion with congestion as their 3 cases of primary laryngeal tuberculosis showed irregular mucosa involving the entire length of the vocal fold, unilaterally in two cases and bilaterally in one [11].

In our study, the patient who had secondary laryngeal tuberculosis, had a “dirty larynx” picture which aided in the diagnosis. However, surprisingly, in spite of having an active foci in the lungs, the patient presented with hoarseness and laryngeal symptoms rather than pulmonary symptoms which resonates with the study done by Lodha et al. [7].

Conclusion

We had 3 cases of laryngeal tuberculosis over a 1 year period. ESR was an unpredictable marker and none of the patients who presented to us had the classical constitutional symptoms of tuberculosis.

In today’s scenario, primary laryngeal tuberculosis appears typically as a unilateral congested vocal fold or as leukoplakic patches on the vocal fold, while secondary laryngeal tuberculosis usually presents as a “dirty larynx” picture with widespread appearance of white patches [slough] over the larynx.

Along with routine TB workup, surgical excision with histopathological testing and TB Bactec culture is essential for accurate diagnosis. The healing of the larynx and the vocal outcomes for the patient are good in both primary and secondary laryngeal TB, once the appropriate antitubercular regimen has been started.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author Contribution

Nupur Kapoor Nerurkar: Concepts, Design, Definition of intellectual content, Literature search, Data acquisition, Data analysis, Statistical analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript editing, Manuscript review, Guarantor. Jahnavi: Design, Definition of intellectual content, Literature search, Data acquisition, Data analysis, Statistical analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript editing, Manuscript review.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Informed Consent

Not Applicable.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Yes.

Ethical Committee approval

Enclosed [Institutional ethics committee approval obtained] – BH-EC-0139.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ayodele A, Oluwapelumi O, Babatunde B, Tolulope B, Abayomi S. Primary laryngeal Tuberculosis as a cause of persistent Hoarseness—A Case Report. Case Rep Clin Med. 2021;10:220–225. doi: 10.4236/crcm.2021.108028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saldanha M, Sima NH, Bhat VS, Kamath SD, Aroor R. Present scenario of laryngeal Tuberculosis. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;4:242–246. doi: 10.18203/issn.2454-5929.ijohns20175633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakthivel P, Singh CA, Sharma SC, Kanodia A, Jat B, Rajeshwari M. Primary laryngeal tuberculosis-the great masquerader. Clin Case Rep Rev. 2017;3:1–3. doi: 10.15761/CCRR.1000335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim JY, Kim KM, Choi EC, Kim YH, Kim HS, et al. Current clinical propensity of laryngeal Tuberculosis: review of 60 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:838–842. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizzo PB, Da Mosto MC, Clari M, Scotton PG, Vaglia A, et al. Laryngeal Tuberculosis: an often forgotten diagnosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2003;7:129–131. doi: 10.1016/S1201-9712(03)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin JE, Nam SY, Yoo SJ, Kim SY. Changing trends in clinical manifestations of laryngeal Tuberculosis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1950–1953. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200011000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodha JV, Sharma A, Virmani N, Bihani A, Dabholkar JP. Secondary laryngeal Tuberculosis revisited. Lung India. 2015;32:462–464. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.164163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harney M, Hone S, Timon C, Donnelly M. Laryngeal Tuberculosis: an important diagnosis. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:878–880. doi: 10.1258/0022215001904220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynrah KG, Tiewsoh I, Marbaniang E, Barman B, Synrem E, et al. Laryngeal Tuberculosis not uncommon in the Present era. J Tuberc Ther. 2018;3:118. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponni S Primary laryngeal tuberculosis-changing trends and masquerading presentations: a retrospective study. International Journal of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and, Surgery N et al (2019) [S.l.], v. 5, n.3, p. 634–638, apr. ISSN 2454–5937

- 11.Guan LS, Jun TK, Azman M, Baki MM (2022) Primary Laryngeal Tuberculosis Manifesting as Irregular Vocal Fold Lesion. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. ;60(1):47–52. doi: 10.4274/tao.2021.2021-7-1. Epub 2022 May 12. PMID: 35634235; PMCID: PMC9103562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Swain SK, Behera IC, Sahu MC. Primary laryngeal Tuberculosis: our experiences at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. J Voice. 2019;33:812e9–81214. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal R, Gupta L, Singh M, Yashaswini N, Saxena A, Khurana N, et al. Primary laryngeal Tuberculosis: a series of 15 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:339–343. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0970-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swain S, Sahu M, Parida J (2016) Wegener’s granulomatosis causing subglottic stenosis: Experiences at a tertiary care hospital of the Eastern India. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 11. 10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.01.005

- 15.Garg SK, Nerukar NK. Childhood Wgener’s granulomatosis with subglottic stenosis. IJOPL. 2011;1(2):71e73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuzuki K, Fukazawa K, Takebayashi H, Hashimoto K, Sakagami M. Difficulty of diagnosing Wegener’s granulomatosis in the head and neck region. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:64e70. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bower JS, Belen JE, Weg JG, Dantzker DR (1980) Manifestations and treatment of laryngeal sarcoidosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. ;122(2):325 – 32. 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.2.325. PMID: 7416609 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Huon LK, Fang TY. Primary laryngeal Tuberculosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011;110(12):792–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grover S, Singh T, Sibia KK, Sarin V. Tuberculosis in larynx. Indian J Respir Care. 2019;8:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishiike S, Irifune M, Sawada T, Doi K, Kubo T. Laryngeal Tuberculosis: a report 15 cases. Annals of Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111(10):916–918. doi: 10.1177/000348940211101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]