Abstract

Computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard for diagnosing sinusitis and anatomical variations and a guide for paranasal sinus (PNS) surgeries. High doses of radiation lead to increased risk of head and neck malignancies, radiation-induced cataracts, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism. The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of low-dose CT as compared to standard-dose CT in the identification of anatomical variants of paranasal sinus and rhinosinusitis. This was a prospective cross-sectional study consisting of 72 patients who were divided equally into cases (underwent low-dose CT for PNS) and controls (underwent CT for PNS using standard dose protocols). Prevalence of anatomical variants and sinusitis were compared. Image quality was assessed using volume CT dose index (CTDIvol), dose length product (DLP), scan length, and noise. Subjective assessment was done by two radiologists, and scores were given. The comparison and analysis of the quantitative and qualitative variables were done. Anatomical variants were comparable among cases and controls, with post-sellar sphenoid being most common and paradoxical middle turbinate being least common surgically important variant. The difference in mean SD of CTDIvol (mGy), DLP (mGy-cm), effective dose (mSv), globe, and air noise between low and standard doses was statistically significant. A moderate agreement (with kappa 0.50) in cases and substantial agreement (with kappa 0.69) in controls was observed between both observers. Low-dose CT PNS and standard-dose CT PNS are comparable in delineating the paranasal sinus anatomy, with a 3.53× reduction of effective radiation dose to patients.

Keywords: Paranasal sinus, Anatomical variants, Surgically important variants, Low dose NCCT PNS, Noise, Rhinosinusitis, CTDIvol, Dose length product (DLP), Effective dose

Introduction

Paranasal sinus (PNS) diseases affect a wide range of populations and include a broad spectrum of diseases ranging from benign to malignant conditions. The most common among these diseases is rhinosinusitis, with a prevalence of around 15% in India [1]. The disease not only affects the quality of life but also has a significant socioeconomic burden on patients [2]. Imaging in rhinosinusitis is recommended in patients who fail to respond to medical treatment, have recurrent sinusitis, or when an alternate diagnosis of neoplasia or fungal infection is suspected [3].

Computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard for diagnosing inflammatory sinus disease and anatomical variations. Anatomical variants were studied in two categories: surgically important variants and surgically non-important variants. CT is rapid and provides isotropic and multiplanar reformatted images, thereby acting as a guide for identifying nasal and paranasal sinus anatomy. The identification of some anatomic variants beforehand plays a crucial role in planning the approach for various PNS surgeries, especially when endoscopic surgery is being considered, thereby decreasing the risk of injury to nearby structures [4].

Although CT is a relatively efficient diagnostic procedure, exposure of the patients to high doses of radiation warrants caution in view of an increased risk of head and neck malignancies, radiation-induced cataracts, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism. Since the maximum image quality may not be critical to therapeutic decision-making in rhinosinusitis, great efforts have been made to decrease the radiation dose (R). For a given scanner and set of acquisition parameters, the volume CT dose index (CTDIvol) is fixed, independent of patient size and scan length, and indicates the intensity of the radiation being directed at the patient. The dose length product (DLP) is the product of the CTDIvol and scan length (in centimeters) and is measured in milligray-centimetres. It indicates the total amount of radiation used to perform the CT examination [5]. The tube current setting during scan acquisition is the most important parameter that affects radiation dose and image quality. It is usually selected to use the minimum radiation required for diagnostic image quality. Since the last two decades, attempts have been made to adopt low-dose methods in view of the high inherent contrast structures in PNS CT. Techniques like iterative reconstruction, an image reconstruction technique that reduces noise and improves image quality, have furthered the initiative of low-dose imaging. With low-dose CT, the radiation dose can be decreased to 22% of that of standard-dose CT without affecting the image quality [6].

The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of low-dose CT in identifying common anatomic variations in the nose and PNS as compared to standard-dose CT PNS and to estimate the association of the different variants with rhinosinusitis.

Material and Methods

This was a prospective cross-sectional study conducted on patients with clinical suspicion of rhinosinusitis for a period of 1 year, from July 2019 to June 2020. Patients with clinical suspicion of rhinosinusitis who gave written and informed consent for participation were included in the study. Patients with a history of craniofacial trauma, sinonasal malignancy, past-history of surgery in the paranasal sinus region, and pregnant women were excluded from the study. The patients were further divided into two groups: cases and controls, randomly using computer software. The study was in accordance with the approved ethical standards of the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Validated informed and written consents were obtained from the patients, and detailed history-taking with clinical examination was done. The study was done on a 64-slice MDCT scanner (Light Speed VCT-Xte, GE Medical Systems). Scanning was commenced from the lower margin of the mandible to the vertex of the head, covering an approximate FOV of 14–16 cm with the patient in a supine position. Data was acquired in the craniocaudal direction. No breath hold was required for imaging. The cases received low-dose CT (100 kV, 60 mAs), and the controls (120 kV, 335 mAs) were scanned with the standard dose protocol for PNS. The rest of the parameters were the same for both cases and controls, i.e., detector collimation of 0.75, helical thickness of 0.625 mm, table pitch and speed (mm/rot) of 0.531:1 and 10.62, gantry rotation time of 0.6 s, scan time of 12.56 s, SFOV head of 14–16 cm, and gantry tilt of 0°.

All four paranasal sinuses (frontal, maxillary, ethmoidal, and sphenoidal sinuses) were assessed for the wall of the sinuses and nasal cavities, anatomical variations of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity, mucosal and soft tissue thickening, fluid level, soft tissue extension, hyperdensities and masses, osteomeatal/drainage pathways, bony involvement, and the presence of surgically important variants. Mucosal thickening > 1 mm was considered positive for rhinosinusitis [7]. Axial, sagittal, and coronal images were reconstructed from isotropic voxels with a slice thickness of 0.625 mm.

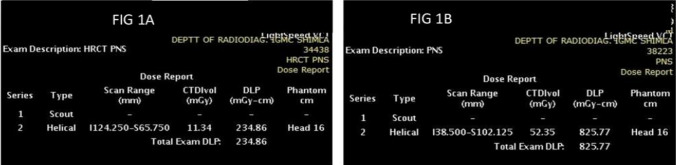

CTDIvol, scan length, and DLP were obtained from the scanner console, and the image quality of both groups was compared (Fig. 1). To calculate the effective dose (mSv), the DLP was multiplied by the appropriate conversion coefficient (k) for the facial skull (k = 0.0023 mSv/mGy cm) as proposed by the European Working Guidelines on Quantity Criteria in CT [8].

Fig. 1.

Exposure parameters and dose details for low dose (Fig. 1A) and standard dose (Fig. 1B)

For the assessment of image quality, objective and subjective parameters were used. For objective assessment, noise generated in the images was measured by placing four circular regions of interest (ROI) with a diameter of 10 mm in both the globes just proximal to the maxillary sinus and in the air outside the globe at this level. The mean SD of globe noise on right (SDgR), left (SDgL), and mean CT attenuation (globe noise) at low and standard dose CT were measured. Similarly, mean SD of air noise on right (SDaR), left (SDaL), and mean CT attenuation (air) at low and standard dose were also calculated (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Measurement of the image noise with region of interest in each globe on right and left side and adjacent air at low dose (Fig. 2A) and standard dose (Fig. 2B)

For subjective assessment, image quality was evaluated on a diagnostic monitor. Two radiologists, who were blinded to the tube current and voltage, evaluated the sharpness of relevant structures (osteomeatal complex, lamina papyracea, cribriform plate, optic nerve, and internal carotid artery bony boundaries) on a 5-point scale, with ‘1’ corresponding to poor image quality and ‘5’ to excellent image quality. In addition, both readers were completely blinded to the clinical details of the patients.

The presentation of categorical variables was done in the form of numbers and percentages (%), and continuous variables were done as mean SD and median values. The comparison and analysis of the quantitative variables were done using an independent t test (for two groups). Similarly, the comparison and analysis of the qualitative variables were done using the Chi-Square test and Fisher’s exact test. The final analysis was done with the use of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 21.0 [9]. For statistical significance, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and Observations

A total of 72 patients with clinical suspicion of rhinosinusitis were included in the study and were randomly divided into two groups: low dose (cases) and standard dose (controls). In all the patients, various demographic and anatomical variations were studied.

Among both the cases and controls groups, the maximum number of patients were in the age group 31–40 years (12 patients among cases (33.33%) and 9 patients among controls (25%), and the minimum number of patients were in the age group 61–70 years (2 patients among cases (5.56%) and 1 patient among controls (2.78%)). There were 19 (52.78%) females and 17 (47.22%) males in cases, and 17 (47.22%) females and 19 (52.78%) males among controls, respectively.

Among the surgically important variants, the most common variant was post-sellar sphenoid sinus which was found in 25 (69.44%) of cases and 22 (61.11%) controls. The least common surgically important variant was the paradoxical middle turbinate, seen in 3 (8.33%) patients among both cases and controls (Table 1). Agger nasi was the most common non-surgically important variant seen in both groups: 28 (77.78%) cases and 29 (80.56%) controls, followed by pneumatized nasal septum, concha bullosa, and maxillary sinus septum. Hypoplastic frontal sinus was the least common non-surgically important variant seen in 7 (19.44%) cases and 4 (11.11%) controls.

Table 1.

Distribution of surgically important variants among low and standard doses

| Surgically important variants | Low dose | Standard dose | Total | p value | Test performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviated nasal septum | 22 (61.11%) | 21 (58.33%) | 43 (59.72%) | 0.81 | Chi square test, 0.058 |

| Paradoxical middle turbinate | 3 (8.33%) | 3 (8.33%) | 6 (8.33%) | 1 | Fisher Exact test |

| Haller cell | 14 (38.89%) | 12 (33.33%) | 26 (36.11%) | 0.624 | Chi square test, 0.241 |

| Onodi cell | 8 (22.22%) | 12 (33.33%) | 20 (27.78%) | 0.293 | Chi square test, 1.108 |

| Post-sellar sphenoid | 25 (69.44%) | 22 (61.11%) | 47 (65.28%) | 0.458 | Chi square test, 0.551 |

| VC endosinal | 18 (50%) | 18 (50%) | 36 (50%) | 1 | Chi square test, 0 |

| FR endosinal | 10 (27.78%) | 13 (36.11%) | 23 (31.94%) | 0.448 | Chi square test, 0.575 |

| ICA endosinal | 14 (38.89%) | 14 (38.89%) | 28 (38.89%) | 1 | Chi square test, 0 |

| Intrasinus septum to ICA | 15 (41.67%) | 11 (30.56%) | 26 (36.11%) | 0.326 | Chi square test, 0.963 |

| Intrasinus septum to the optic nerve | 22 (61.11%) | 12 (33.33%) | 34 (47.22%) | 0.018 | Chi square test, 5.573 |

VC, vidian canal; FR, foramen rotundum; ICA, internal carotid artery

Maxillary sinusitis was seen in the maximum number of patients in both groups: 24 (66.67%) cases and 27 (75.00%) controls. Pansinusitis was least common in both groups (9 (25%) patients among both cases and controls). In patients with rhinosinusitis, Agger Nasi was the most common variant (13 (68.42%) patients), followed by a deviated nasal septum in 11 (57.89%) patients.

The mean SD of CTDIvol (mGy), DLP (mGy-cm), and effective dose (mSv) difference between low and standard doses was statistically significant with a p value 0.0001, as shown in Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of CT DI volume (mGy) between low and standard doses

| CT DI volume (mGy) | Low dose (n = 36) |

Standard dose (n = 36) |

Total | p value | Test performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SD | 11.34 ± 0 | 43.7 ± 5.77 | 27.52 ± 16.79 | <0 .0001 | t test; 33.657 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 11.34(11.34–11.34) | 42.98(40.562–46.8) | 22.07(11.34–42.96) | ||

| Range | 11.34–11.34 | 32.8–59.23 | 11.34–59.23 |

Table 3.

Comparison of DLP (mGy-cm) between low and standard doses

| DLP (mGy-cm) | Low dose (n = 36) |

Standard dose (n = 36) |

Total | p value | Test performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SD | 211.79 ± 18.7 | 751.79 ± 95.44 | 481.79 ± 280.34 | <0 .0001 | t test; 33.316 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 209(201.975–219.622) | 748.56(707.705–794.725) | 394.52(209.172–747.728) | ||

| Range | 163.99–250.53 | 538.51–1023.13 | 163.99–1023.13 |

Table 4.

Comparison of effective dose (mSv) between low and standard doses

| Effective dose (mSv) | Low dose (n = 36) |

Standard dose (n = 36) |

Total | p value | Test performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SD | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 1.73 ± 0.22 | 1.11 ± 0.64 | < 0.0001 | t test; 33.32 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 0.48(0.464–0.504) | 1.72(1.627–1.828) | 0.91(0.48–1.719) | ||

| Range | 0.38–0.58 | 1.24–2.35 | 0.38–2.35 |

There was a statistically significant difference between the mean SD of globe noise on right (SDgR), left (SDgL), and mean CT attenuation (globe noise) at low and standard dose CT with a p value of 0.0001 (Table 5). Similarly, a statistically significant difference was seen in the mean SD of air noise on right SDaR, SDaL, and mean CT attenuation (air) at low and standard dose with a p value of 0.0001 (Table 6).

Table 5.

Comparison of globe noise between low and standard doses

| Globe noise | Low dose (n = 36) |

Standard dose (n = 36) |

Total | p value | Test performed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDgR | Mean SD | 27.3 ± 6.87 | 14.7 ± 3.13 | 21 ± 8.27 | < 0.0001 | t test; 10.017 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 26.34(22.555–32.01) | 14.39(12.535–15.752) | 19.24(14.455–25.862) | |||

| Range | 15.39–50.01 | 8.85–24.58 | 8.85–50.01 | |||

| SDgL | Mean SD | 27.34 ± 5.44 | 14.96 ± 3.76 | 21.15 ± 7.77 | < .0001 | t test;11.227 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 27.74(24.182–31.048) | 14.96(12.27–17.042) | 19.65(15.067–27.465) | |||

| Range | 17.25–38.83 | 7.75–25.36 | 7.75–38.83 | |||

| Mean globe | Mean SD | 27.32 ± 4.46 | 14.83 ± 2.92 | 21.07 ± 7.32 | < .0001 | t test;14.052 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 27.34(24.724–30.829) | 14.72(12.581–16.475) | 20.06(14.81–27.325) | |||

| Range | 16.74–35 | 10.57–24.97 | 10.57–35 |

Table 6.

Comparison of air noise between low and standard doses

| Air | Low dose (n = 36) |

Standard dose (n = 36) |

Total | p value | Test performed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDaR | Mean SD | 20.96 ± 4.47 | 11.55 ± 2.6 | 16.26 ± 5.97 | < 0.0001 | t test; 10.926 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 21.38 (18.558–22.942) | 11.24 (9.515–13.772) | 15.06 (11.118–21.322) | |||

| Range | 10.29–36.49 | 7.37–18.52 | 7.37–36.49 | |||

| SDaL | Mean SD | 21.62 ± 4.71 | 10.7 ± 1.87 | 16.16 ± 6.55 | < 0.0001 | t test; 12.944 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 21.68 (18.893–23.935) | 10.5 (9.145–11.88) | 14.1 (10.562–21.578) | |||

| Range | 11.49–31.44 | 6.95–14.88 | 6.95–31.44 | |||

| Mean air | Mean SD | 21.29 ± 3.87 | 11.12 ± 1.67 | 16.21 ± 5.91 | < 0.0001 | t test; 14.47 |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 20.75 (19.32–23.451) | 11.12 (9.753–12.514) | 14.09 (11.048–20.71) | |||

| Range | 10.89–33.97 | 8.15–14.16 | 8.15–33.97 |

For the subjective assessment of image quality, a subjective image score of 1–5 was given to each of the cases after proper blinding. The mean score and standard deviation for the low dose (cases) by observer 1 were 4.00 and 0.78, and for observer 2, they were 4.16 and 0.69, respectively. For the standard dose (controls) group, the mean and standard deviation by observer 1 were 3.88 and 0.88, and by observer 2, they were 4.08 and 0.87, respectively.

A moderate agreement existed between observer 1 and observer 2, with a kappa of 0.50 and a p value of 0.023 in the evaluation of low-dose CT. The overall concordance rate was 69.44%, and the overall discordance rate was 38.44%. Among the controls, substantial agreement existed between observer 1 and observer 2, with a kappa of 0.69 and a p value of 0.015. The overall concordance rate was 75%, and the overall discordance rate was 31.86%.

Discussion

Due to its widespread availability, convenience of use, and diagnostic information obtained, computed tomography (CT) has become the modality of choice to evaluate the diseases of the nose and paranasal sinuses, which has led to an increase in the number of scans performed annually to diagnose PNS pathologies [10]. This has led to increased radiation exposure and the associated cancer risk, which is of concern, especially in children and young adults [11]. Moreover, patients with chronic PNS diseases require repeated imaging during their disease, thus exposing them to increased radiation exposure. Hence, efforts are in place to reduce the amount of radiation given to the patients. One such method is to reduce the effective dose, and, in that manner, the amount of radiation given to the patients. But, on reducing the dose, the images obtained are of poor quality and are associated with increased noise. Iterative reconstruction (IR) is an algorithm-based reconstruction method to improve image quality and reduce noise. In our study, we attempted to compare low-dose CT of PNS with standard-dose CT of PNS (both using iterative reconstruction techniques) to identify various anatomical variations, observe the association of the variants with rhinosinusitis in both methods, and evaluate if it is possible to reduce the patient dose without a major deterioration of the image quality to reach a diagnosis.

A total of 72 patients were enrolled in the study and were divided equally into cases (those who received low-dose radiation) and controls (those who received standard-dose radiation) after randomization. There were 17 (47.22%) males and 19 (52.78%) females among the cases, and 19 (52.78%) males and 17 (47.22%) females among the controls. The mean SD of age was 39.97 ± 13.57 years among cases and 37.08 ± 14.52 years among controls. In both groups, the maximum number of patients was in the age group of 31–40 years.

The presence of surgically important variants (Fig. 3) was assessed in both cases and controls. The maximum number of patients had post-sellar sphenoid among low and standard dose groups, followed by a deviated nasal septum. Post-sellar sphenoid was seen in 25 (69.44%) cases and 22 (61.11%) controls. A deviated nasal septum was found to be present in 22 (61.11%) cases and 21 (58.33%) controls. Among patients with deviation of the nasal septum, it was found to be towards the left in 10 (45.45%) cases and 10 (47.62%) controls and towards the right among 12 (54.55%) cases and 11 (52.38%) controls, with no statistically significant difference (p-value 0.887). Similar findings were found in a study by Harugop et al., where DNS was seen to the left in 46.93% and towards the right in 51.02% [12]. No statistically significant difference was seen in the prevalence of surgically important variants among the low-dose and standard-dose groups. Apart from these, surgically non-important variants had no statistically significant difference between low-dose CT PNS and standard-dose CT PNS.

Fig. 3.

Coronal sections of CT PNS—low dose (Fig. 3A) and standard dose (Fig. 3B) showing paradoxical middle turbinate (white arrow) and right maxillary antral polyp (black arrow in Fig. 3B). Sagittal sections of CT PNS—low dose (Fig. 3C) and standard dose (Fig. 3D) showing post sellar sphenoid sinus (white arrow). Axial sections of CT PNS—low dose (Fig. 3E) and standard dose (Fig. 3F) showing intra-sinus septum to left internal carotid artery (ICA) (white arrow) and endosinal ICA (black arrow, Fig. 3F). Coronal sections of CT PNS (low dose) showing bilateral endosinal vidian canal (white arrow) and endosinal foramen rotundum (black arrow) (Fig. 3G) and standard dose (Fig. 3H) showing right endosinal foramen rotundum (black arrow).

Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference seen among various sinusitis between low and standard dose CT PNS. Agger nasi cell was the most common variant associated with all the types of sinusitis and rhinosinusitis in low and standard doses. The paradoxical middle turbinate was the least common variant associated with sinusitis in both low and standard doses. Similar findings were also found in studies by Brunner et al. [13] and Bradley et al. [14]. Enlargement of the Agger nasi leads to narrowing of the nasofrontal duct medially, which explains its association with chronic frontal rhinosinusitis [14]. Moreover, the anterior osteomeatal unit drains the maxillary, anterior ethmoid, and frontal sinuses. Occasionally, anatomical variants like Agger nasi and Concha bullosa could affect the patency of this unit, leading to the development of sinusitis in these sinuses.

Maxillary sinus was the most common sinus to be involved by sinusitis in a total of 70.83% of patients, followed by middle ethmoid, posterior ethmoid, anterior ethmoid, sphenoid, and frontal sinus. Pansinusitis was the least common (18%). Rhinosinusitis was present in 45.83% of patients. Our study correlates well with other studies done by Kandukuri et al. [15], Suthar et al. [16], and Chaitanya et al. [17], where the maxillary sinus was the most involved sinus for sinusitis. In the study by Vaghela et al. [18] the maxillary sinus was the most involved sinus by sinusitis (85%), and the frontal sinus was the least commonly involved (57%) among the four sinuses. Similar findings were also present in the study by Pawar et al. [19] where maxillary sinusitis was seen in 70% of the patients and pansinusitis was seen in 10% of the patients.

The CTDIvol, DLP, and effective dose administered were elaborately compared as markers of the radiation dose being given to the patients. The mean DLP was 211.79 ± 18.7 mGy-cm among cases and 751.79 ± 95.44 mGy-cm among controls, with a significant statistical difference (p-value 0.0001). Similarly, we recorded a CTDIvol of 11.34 mGy among cases and 43.7 ± 5.77 mGy among controls (p-value 0.0001). The effective dose received by cases was 0.49 ± 0.04 mSv, which was 3.53× lower than the controls who received 1.73 ± 0.22 mSv, with a p-value of 0.0001. This shows that all the parameters of the dose given to the patients were significantly lower at the low dose as compared to the standard dose CT.

It is a well-known phenomenon that the noise increases as the dose decreases, which means a decrease in the clarity of the images obtained [20]. To assess the objective image quality, we compared the noise of the globe and air between low and standard doses. The mean noise (globe) was 27.32 ± 4.46 among cases and 14.83 ± 2.92 among controls, with a p-value of 0.0001. The mean noise (air) was 21.29 ± 3.87 among cases and 11.12 ± 1.67 among controls, with a p-value of 0.0001. This suggests that there was a significant increase in the noise in the images obtained with a low dose as compared to the images obtained with a standard dose. Similar findings have been observed in studies by Lam et al. [21] and Ma et al. [22].

Subjective image quality was evaluated on a diagnostic monitor for image sets. Two radiologists, who were blinded to the dose details, evaluated the overall image quality subjectively. The Kappa statistics score was 0.5 for low dose, implying moderate agreement, and 0.69 for standard dose, suggesting substantial agreement. So, we inferred that despite the statistically significant increase in noise on reduction of the dose, the overall image quality was enough to reach a clinically relevant diagnosis, and no statistically significant difference was observed in the sharpness of relevant structures, as well as in identifying the different variants and presence of rhinosinusitis by both observers.

These findings correlate well with other studies like that by Tack et al., where no significant differences were observed when identifying mucosal or bony abnormalities in the sinonasal cavities between low-dose and standard-dose MDCT [23]. Similarly, Duvoisin et al. found no difference in the assessment of inflammatory diseases of the paranasal sinuses among low- and standard-dose CT despite increased noise [24].

Although it is commonly believed that a high radiation dose is generally required for the delineation of the bony structures, we found that low-dose CT was equally efficient in their identification. Similarly, in a study by Schaafs et al., it was found that by using a low-dose protocol in conjunction with iterative reconstruction (IR), a significant reduction of the effective dose of 82% compared with a non-dose-reduced protocol and 20% compared with a conventional low-dose protocol was obtained.

The study also showed that the combination of dose reduction and IR significantly improved the image quality and distinction of anatomic landmarks compared with low-dose CT using filtered back projection (FBP) [25]. Similarly, in the study by Stefan Bulla et al., the iterative reconstruction technique allowed for a significant dose reduction of up to 60% for paranasal-sinus CT without impairing the diagnostic image quality as compared to filtered back projection [26]. Similar conclusions were also reached by Hoxworth et al. [27] and Schulz et al. [28], where it was observed that iterative reconstruction techniques reduced image noise as compared to FBP. However, no such comparison was possible in our study as both low-dose and standard-dose CT used IR techniques.

Some of the limitations of our study were the small sample size and the fact that it was restricted to one region only, so regional variations in the prevalence of anatomical variants and types of sinusitis could not be studied. Our study used iterative reconstruction techniques for both low-dose and standard-dose CT PNS, so comparison with other techniques like FBP (for dose reduction) was not feasible in our study, yet it clearly demonstrated the possibility of CT acquisition at a lower dose without significantly compromising the diagnostic image quality.

Conclusion

Low-dose CT PNS is equally effective as standard-dose CT PNS in delineating the paranasal sinus anatomy with its variants and the presence of sinusitis. A slight increase in the noise associated with low-dose CT PNS is compensated by a substantial decrease of 3.53 times the effective radiation dose received by the patient. Hence, low-dose CT PNS can be recommended for assessment of the paranasal sinuses, especially in chronic diseases like sinusitis where patients require repeated imaging.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest for this study.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by institutional ethical committee/board.

Informed Consent

Written and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.O’Brien WT, Sr, Hamelin S. Weitzel EK The preoperative sinus CT: avoiding a—CLOSE call with surgical complications. Radiology. 2016;281(1):10–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fatterpekar GM, Delman BN, Som PM. Imaging the paranasal sinuses: where we are and where we are going. Anat Rec Adv Integr Anat Evolut Biol. 2008;291(11):1564–1572. doi: 10.1002/ar.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shashy RG, Moore EJ, Weaver A. Prevalence of the chronic sinusitis diagnosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):320–323. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas JW, Schiller JS, Benson V (2004) Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health interview Survey, 2001. Vital Health Stat 10. 2004 Jan. 1-134.37 [PubMed]

- 5.Formby ML. The maxillary sinus. Proc R Soc Med. 1960;53:163–168. doi: 10.1177/003591576005300302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tange RA. Some historical aspects of the surgical treatment of the infected maxillary sinus. Rhinology. 1991;29:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shpilberg KA, Daniel SC, Doshi AH, Lawson W, Som PM. CT of anatomic variants of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity: poor correlation with radiologically significant rhinosinusitis but importance in surgical planning. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(6):1255–1260. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bongartz G, Golding SJ, Jurik AG et al (1999) European guidelines on quality criteria for computed tomography. Rep EUR. 16262

- 9.IBM Corp. Released (2013) IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, Version 21.0. IBM Corp, Armonk

- 10.Babbel R, Harnsberger HR, Nelson B, Sonkens J, Hunt S. Optimization of techniques in screening CT of the sinuses. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12(5):849–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JX, Kachniarz B, Gilani S, Shin JJ. Risk of malignancy associated with head and neck CT in children: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(4):554–566. doi: 10.1177/0194599814542588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harugop AS, Mudhol RS, Hajare PS, Nargund AI, Metgudmath VV, Chakrabarti S. Prevalence of nasal septal deviation in new-borns and its precipitating factors: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;64(3):248–251. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0247-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner E, Jacobs JB, Shpizner BA, Lebowitz RA, Holliday RA. Role of the agger nasi cell in chronic frontal sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105(9):694–700. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley DT, Kountakis SE. The role of agger nasi air cells in patients requiring revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(4):525–527. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandukuri R, Phatak S. Evaluation of sinonasal diseases by computed tomography. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(11):TC09–TC12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/23197.8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suthar BP, Vaidya D, Suthar PP. The role of computed tomography in the evaluation of paranasal sinuses lesions. Int J Res Med. 2015;4(4):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaitanya CS, Raviteja A. Computed tomographic evaluation of diseases of paranasal sinuses. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2015;6(7):5081–5086. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaghela K, Shah B. Evaluation of paranasal sinus diseases and its histopathological correlation with computed tomography. J Oral Med Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;4(1):11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawar SS, Bansal S. CT anatomy of paranasal sinuses–corelation with clinical sinusitis. Int J Contemp Med Res IJCMR. 2018;5(4):3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu L, Liu X, Leng S, et al. Radiation dose reduction in computed tomography: techniques and future perspective. Imaging Med. 2009;1(1):65–84. doi: 10.2217/iim.09.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam S, Bux S, Kumar G, Ng KH, Hussain A. A comparison between low-dose and standard-dose non-contrasted multidetector CT scanning of the paranasal sinuses. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2009;5(3):e13. doi: 10.2349/biij.5.3.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J, Huang J, Feng Q, et al. Low-dose computed tomography image restoration using previous normal-dose scan. Med Phys. 2011;38(10):5713–5731. doi: 10.1118/1.3638125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tack D, Widelec J, De Maertelaer V, Bailly JM, Delcour C, Gevenois PA. Comparison between low-dose and standard-dose multidetector CT in patients with suspected chronic sinusitis. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(4):939–944. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1810939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duvoisin B, Landry M, Chapuis L, Krayenbuhl M, Schnyder P. Low-dose CT and inflammatory disease of the paranasal sinuses. Neuroradiology. 1991;33(5):403–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00598612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaafs LA, Lenk J, Hamm B, Niehues SM. Reducing the dose of CT of the paranasal sinuses: potential of an iterative reconstruction algorithm. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2016;45(7):20160127. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulla S, Blanke P, Hassepass F, Krauss T, Winterer JT, Breunig C, Langer M, Pache G. Reducing the radiation dose for low-dose CT of the paranasal sinuses using iterative reconstruction: feasibility and image quality. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(9):2246–2250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoxworth JM, Lal D, Fletcher GP, Patel AC, He M, Paden RG, et al. Radiation dose reduction in paranasal sinus CT using model-based iterative reconstruction. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:644–649. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz B, Beeres M, Bodelle B, Bauer R, Al-Butmeh F, Thalhammer A, Vogl TJ, Kerl JM. Performance of iterative image reconstruction in CT of the paranasal sinuses: a phantom study. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(5):1072–1076. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]