Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep-related breathing disorder that affects almost one billion individuals worldwide. An estimated 16.8% of adults in Jordan have been diagnosed with OSA. Given the importance of management of OSA by otolaryngologists, we assessed the knowledge and attitudes of Jordanian otolaryngologists in managing OSA in adult and pediatric patients. A survey, conducted anonymously online, was sent present otolaryngology residents and specialist in Jordan, in the English language. The participants were given the OSA Knowledge and Attitude questionnaire (OSAKA, OSAKA-KIDS), which have been previously validated. Data were obtained and then analyzed via SPSS software. A total of 140 residents and specialist of otolaryngology were selected. A significant difference in OSAKA scores were found between otolaryngologists under 30 years of age and those above, with higher scores for the older age group. The proportion of specialists who ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ they are confident in their ability to manage patients with OSA was significantly higher that junior residents (73.8% vs 33.3%; p = 0.008). More than 10 years at practice was associated with statistically significant higher levels of knowledge towards OSAKA scale (AOR = 0.09; p = 0.044). Additionally, being a senior resident was significantly associated with more knowledge towards OSAKA-KIDS scale (AOR = 0.19; p = 0.03). Otolaryngology residents and specialists’ knowledge of OSA was very good. Further improving in the level of the knowledge toward OSA among the otolaryngology resident doctors should be implemented as possible by following the updated guidelines for the diagnosis and management OSA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12070-023-04180-8.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, OSA, Otolaryngology, Jordan, Knowledge

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder that affects almost 1 billion individuals worldwide [1]. The situation in Jordan is no different, as the prevalence of OSA among adults has been estimated at 16.8% [2]. Untreated adults suffering from OSA are at increased risk of a plethora of conditions, including impaired cognitive functioning, excessive daytime sleepiness, hypertension, arrhythmias, coronary heart disease, and stroke [3–5]. OSA has also been associated with increased risk of road traffic accidents and diminished quality-of-life [6]. In children with OSA, although the clinical presentation is different from adults, the consequences of the condition are as dire[7, 8]. Growth failure, neurobehavioral problems like attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), poor academic achievement, nocturnal enuresis, and depressive symptoms have been associated with pediatric OSA [9–11]. Obesity is a major risk factor of OSA for both children and adults, and with the current obesity pandemic going worldwide, OSA will continue to be a huge burden in the days to come [12].

Patients with OSA face a grim reality of misdiagnosis due to the unfamiliarity of physicians with their condition. Previous studies have shown that primary care physicians have little-to-moderate awareness of OSA, particularly in developing countries [13–16]. Pediatricians have also faced challenges regarding diagnosis and management of OSA in children [17]. Many primary care physicians tend to refer patients with OSA to otolaryngologists, thus otolaryngologists are expected to have a higher level of awareness regarding OSA [18]. Previous studies have shown varying levels of knowledge among otolaryngology residents between different countries, reflecting the discrepancy between residency programs regarding residents’ education and training [19, 20]. This also urges the need for development of educational programs and rotations in the different areas of otolaryngology to consequently produce well-rounded otolaryngology physicians.

However, before establishing new educational strategies for Jordanian residents, we need first to ascertain their level of familiarity and knowledge of this area. Therefore, we conducted this cross-sectional study to assess the knowledge and attitude towards obstructive sleep apnea among otolaryngologists in multiple health sectors using the obstructive sleep apnea knowledge and attitudes (OSAKA) questionnaire along with the obstructive sleep apnea knowledge and attitudes in children (OSAKA-Kids) questionnaire forms.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Setting

This is a cross-sectional investigation conducted from September 2022 and October 2022. We followed the STROBE guidelines (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) while preparing this investigation. The institutional research ethics committee approved the study design and research permission was donated (No.5/6/2021/2022). The privacy of data was maintained according to Helsinki Declaration of bioethics.

Participants and Data Collection

All Jordanian otolaryngologists (both residents and specialists), both genders, in all residency training centers which includes: the ministry of health (MOH), the Jordanian royal medical services hospitals, university hospitals, and the private sector were included in our study. Residency programs and educational materials are similar between the different sectors in Jordan, and they undergo the same evaluation criteria. The program includes five years of training in otorhinolaryngology. We divided residents into Juniors (first- and second-year residents), and Seniors (third-, fourth-, and fifth-year residents). Specialists are considered any board certified otorhinolaryngologists, regardless of their experience. We used the convenience sampling methods for enrolling participants. All registered otorhinolaryngologists in the Jordanian Medical Association (JMA) were contacted via social media platforms groups (mainly WhatsApp).

Sample Size Calculation

All registered otorhinolaryngologists in the JMA (n = 417) were considered the target population. Sample size calculation was done using Raosoft online software. We assumed that 50% of the target population would have good knowledge about OSA with a 5% margin of error and a confidence interval of 80%, the minimum sample size of 119 was determined.

Study Instrument

The questionnaire was applied in English:

OSAKA

The study included Socio-demographic information about subjects, such as: age, gender, specialty, and duration of practice for physicians. To assess their knowledge and attitude towards identifying and managing patients with OSA, the investigators utilized a self-administered questionnaire Obstructive Sleep Apnea Knowledge and Attitudes (OSAKA). The OSAKA is a validated the questionnaire that was developed by Schotland and Jeffe, which includes 18 knowledge items and five questions related to attitudes about OS [21]. The knowledge items cover different OSA domains about epidemiology, pathophysiology, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. For the knowledge items, responses to the questions (true, false, or I don't know) were categorized into correct and incorrect answers. A score of 1 was given for correct answers, while 0 was assigned to other responses. Thus, the knowledge scores ranged from 0 to 18. Regarding attitudes, two questions assessed the importance of OSA, while the remaining three questions focused on physicians' confidence in diagnosing and treating patients with OSA. Participants rated their level of agreement with each item using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

OSAKA-KIDS

The Socio-demographic information are the same items in the OSAKA questionnaire. The OSAKA-KIDS reworded and tailored to children from the OSAKA questionnaire by Uong et al. and consisted of 23 items divided into knowledge and attitudes regarding childhood OSAS [22]. The final questionnaire included 18 knowledge items and five attitude items. The knowledge items cover different childhood OSAS domains about epidemiology, pathophysiology, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Answers to knowledge questions (true, false, I don’t know) were dichotomized into correct and incorrect answers. True was awarded score of 1 and other answers were awarded score of 0. Therefore, knowledge scores ranged between 0 and 18. Two attitude questions asked about the importance of childhood OSAS, and the other three attitude questions dealt with physician’s confidence in diagnosing and treating patients with childhood OSAS. Physicians were asked to rate the extent of their agreement with each item using a five-points Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data Analysis

The research data was analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 28. Statistically significant values were considered when p-values were below 0.05. Quantitative data were presented using mean and standard deviation, while categorical data were assessed using frequency and percentages. The normality of the data was determined to be non-parametric based on the result of the Shapiro–Wilk test. To compare the knowledge levels of sub-groups regarding OSAS, a Kruskal–Wallis test was employed. Finally, using the cutoff values established in the imitated study21,22, we ran a binary logistic regression to determine the predicted values to get acceptable knowledge about OSAS between the independent variables (sociodemographic characteristics) and the dependent variable (knowledge toward OSAS).

Results

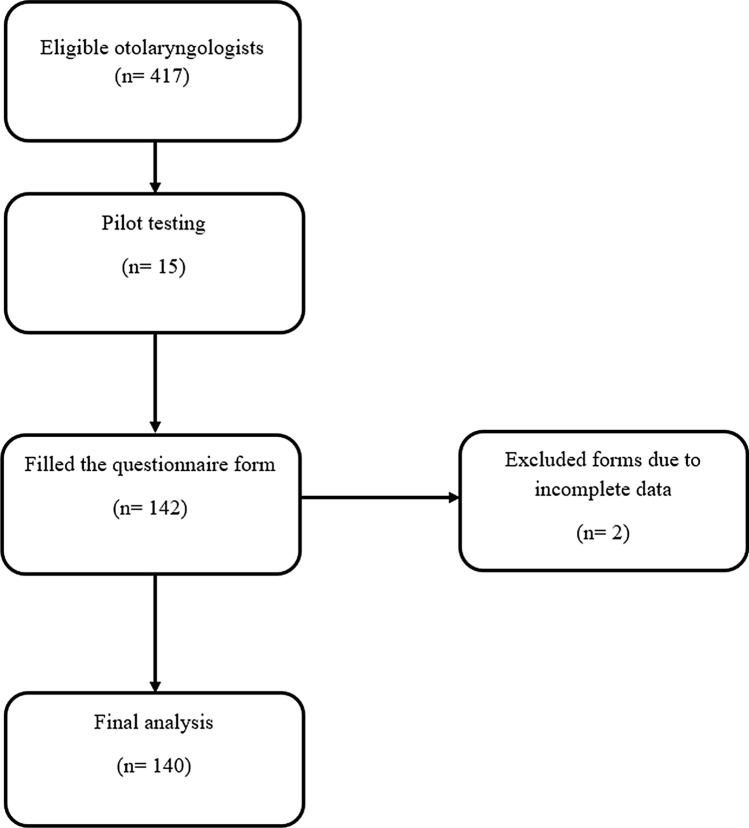

A total of 140 otolaryngologists participated in this study. The median age of participants was 35 years, with 77.9% of participants being males. As shown in Table 1., most otolaryngologists were on the more experienced side, with 70.7% being specialists and 66.5% having at least 5 years of practice. Figure 1.

Table 1.

Summarizes the demographic characteristics of participating otolaryngologists in this study

| Variable | Total = 140, n(%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (median (IQR)) | 35 (32–48.75) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 109 (77.9%) |

| Female | 31 (22.1%) |

| Professional qualification | |

| Junior resident | 15 (10.7%) |

| Senior resident | 26 (18.6%) |

| Specialist | 99 (70.7%) |

| Current practice | |

| Ministry of health | 40 (28.6%) |

| Royal medical services | 38 (27.1%) |

| Private sector | 48 (34.3%) |

| University hospitals | 14 (10%) |

| Duration of practice | |

| < 5 years | 47 (33.6%) |

| 5–10 years | 33 (23.6%) |

| > 10 years | 60 (42.9%) |

| Combined knowledge overall score (median (IQR)) | |

| Total | 27 (24–29) |

| Junior resident | 26 (19–28) |

| Senior resident | 26.50 (22–29.25) |

| Specialist | 27 (24–30) |

Data are presented as frequencies and percentages unless stated otherwise

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of sampling and analysis processes

OSAKA Knowledge Scores

The median knowledge score for all participants was 15 out of 18. Junior residents, as expected, had lower scores (13/18, IQR 11-15) compared to senior residents and specialists (15/18, IQR, 12.75-16) and (15/18 IQR, 14-17), respectively. The percentage of each answer for every question answered by the participants is shown in Table 2. The least three questions answered correctly were related to laser-assisted uvuloplasty not being a treatment for severe OSA (54.3%), the prevalence of OSA (63.6%), and normal number of apnea/hypopneas in adults (65.8%).

Table 2.

Data from the knowledge part of OSAKA questionnaire

| OSAKA knowledge questions (correct answer) | True, n(%) | False, n(%) | IDK, n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women with OSA may present with fatigue alone (True) | 103 (73.6%) | 31 (22.1%) | 6 (4.3%) |

| Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty is curative for majority of patients with OSA (False) | 35 (25%) | 97 (69.3%) | 8 (5.7%) |

| The estimated prevalence of OSA among adults is between 2 and 10% (True) | 89 (63.6%) | 16 (11.4%) | 35 (25%) |

| The majority of patients with OSA snore (True) | 131 (93.6%) | 7 (5%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| OSA is associated with hypertension (True) | 118 (84.3%) | 16 (11.4%) | 6 (4.3%) |

| Overnight sleep study is the gold standard for diagnosing OSA (True) | 128 (91.5%) | 10 (7.1%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Treatment with CPAP can result in nasal congestion (True) | 107 (76.4%) | 20 (14.3%) | 13 (9.3%) |

| Laser-assisted uvuloplasty is an appropriate treatment for severe OSA (False) | 38 (27.1%) | 76 (54.3%) | 26 (18.6%) |

| Loss of upper airway muscle tone during sleep contributes to OSA (True) | 126 (90%) | 10 (7.1%) | 4 (2.9%) |

| The most common cause of OSA in children is the presence of large tonsil and adenoid (True) | 139 (99.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Craniofacial and oropharyngeal examination are useful in a patient with suspected OSA (True) | 135 (96.4%) | 3 (2.2%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Alcohol at bedtime improves OSA (False) | 5 (3.6%) | 114 (81.4%) | 21 (15%) |

| Untreated OSA is associated with higher incidence of automobile crashes (True) | 135 (96.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 4 (2.9%) |

| In man a collar size 43 cm (XL size) or greater is associated with OSA (True) | 103 (73.6%) | 10 (7.1%) | 27 (19.3%) |

| OSA is more common in women than men (False) | 20 (14.3%) | 110 (78.6%) | 10 (7.1%) |

| CPAP is the first therapy for severe OSA (True) | 103 (73.6%) | 31 (22.1%) | 6 (4.3%) |

| Less than 5 Apnea/hypopnea per hour is normal in adults (True) | 92 (65.8%) | 38 (27.1%) | 10 (7.1%) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia may be associated with OSA (True) | 135 (96.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 4 (2.9%) |

| OSAKA overall score (median (IQR)) | |||

| Total | 15 (13–16) | ||

| Junior resident | 13 (11–15) | ||

| Senior resident | 15 (12.75–16) | ||

| Specialist | 15 (14–17) | ||

Data are presented as frequencies and percentages unless stated otherwise

OSA obstructive sleep apnea, CPAP continuous positive airway pressure, IDK I don’t know

OSAKA-KIDS Knowledge Scores

The median knowledge score for all participants was 12 out of 18. Surprisingly, junior residents showed similar knowledge scores (12/18, IQR 11-15) to senior residents (11.5/18, IQR 9-13) and specialists (12/18, IQR 10-14). The percentage of each answer for every question answered by the participants is shown in Table 3. The least three questions answered correctly were related to reliability of detection of central and obstructive apnea in infants by a cardiorespiratory monitor (25.7%), increased risk of OSA in children with sickle cell disease (35%), and correlation between degree of snoring and severity of OSA in infants (39.3%).

Table 3.

Data from the knowledge part of OSAKA-KIDS questionnaire

| OSAKA-KIDS knowledge questions (correct answer) | True, n(%) | False, n(%) | IDK, n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may present with hyperactivity (True) | 59 (42.1%) | 70 (50%) | 11 (7.9%) |

| Approximately 10% of children snore on regular basis (True) | 94 (67.1%) | 22 (15.8%) | 24 (17.1%) |

| Nearly 2% of children have OSA (True) | 84 (60%) | 20 (14.3%) | 36 (25.7%) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea in children may be associated with pulmonary hypertension (True) | 117 (83.6%) | 7 (5%) | 16 (11.4%) |

| A polysomnogram is needed to differentiate primary snoring from obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children (True) | 93 (66.4%) | 26 (18.6%) | 21 (15%) |

| The degree of snoring (i.e. moderate to severe) correlates with the severity of obstructive apnea in children (False) | 72 (51.4%) | 55 (39.3%) | 13 (9.3%) |

| Excessive upper airway muscle tone loss during sleep contributes to OSA in children (True) | 75 (53.6%) | 49 (35%) | 16 (11.4%) |

| Enlarged tonsils and adenoids are the most frequent contributing factor to OSA (True) | 129 (92.1%) | 9 (6.4%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Children with suspected OSA should have thorough head and neck and oropharyngeal examination (True) | 136 (97.2%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Children with untreated OSA may have learning deficits (True) | 135 (96.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| Snoring is most frequently reported at ages 2 to 8 years (True) | 111 (79.3%) | 15 (10.7%) | 14 (10%) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias may be associated with untreated OSA (True) | 125 (89.3%) | 6 (4.3%) | 9 (6.4%) |

| Children with sickle cell disease are at increased risk for OSA (True) | 49 (35%) | 23 (16.4%) | 68 (48.6%) |

| Children younger than 2 years should have a polysomnogram prior to surgical intervention for presumed OSA (True) | 51 (36.4%) | 69 (49.3%) | 20 (14.3%) |

| Significant OSA can occur without snoring in children (True) | 81 (57.9%) | 41 (29.2%) | 18 (12.9%) |

| Failure to thrive can be an associated finding suggesting obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in infants and young children (True) | 129 (92.1%) | 5 (3.6%) | 6 (4.3%) |

| Children with severe OSA may have transient worsening of respiratory symptoms following tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (True) | 102 (72.9%) | 24 (17.1%) | 14 (10%) |

| A cardiorespiratory monitor can reliably detect both central and obstructive apnea in infants (False) | 67 (47.9%) | 36 (25.7%) | 37 (26.4%) |

| OSAKA-KIDS overall score (median (IQR)) | |||

| Total | 12 (10–14) | ||

| Junior resident | 12 (11–15) | ||

| Senior resident | 11.50 (9–13) | ||

| Specialist | 12 (10–14) | ||

Data are presented as frequencies and percentages unless stated otherwise

OSA obstructive sleep apnea, CPAP continuous positive airway pressure, IDK I don’t know

OSAKA and OSAKA-KIDS Attitude Scores

Most respondents (77.1%) reported that OSA is ‘very important’ or ‘extremely important’ clinical disease. Similarly, as shown in Table 4, 75.7% of participants believed it is ‘very important’ or ‘extremely important’ to find the diseases resulting in OSA. Table 5 shows that the proportion of specialists who believed it is ‘very important’ or ‘extremely important’ to find the diseases resulting in OSA was significantly higher than junior residents (81% vs 46.6%; p = 0.008).

Table 4.

Association between attitudes and participants subgroups

| Attitude question | Attitude category | Junior resident n = (15) | Senior resident n = (26) | Specialist n = (99) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstructive sleep apnea from the viewpoint of a clinical disease: | Not important | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.174# |

| Somewhat important | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| Important | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (11.6%) | 20 (20.2%) | ||

| Very important | 4 (26.7%) | 14 (53.8%) | 33 (33.3%) | ||

| Extremely important | 6 (40%) | 8 (30.8%) | 43 (43.5%) | ||

| Finding the diseases resulting in obstructive sleep apnea: | Not important | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.008# |

| Somewhat important | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| Important | 6 (40%) | 7 (27%) | 17 (17.2%) | ||

| Very important | 4 (26.6%) | 16 (61.4%) | 46 (46.7%) | ||

| Extremely important | 3 (20%) | 3 (11.6%) | 34 (34.3%) | ||

| I have enough self-confidence to find a patient who is at risk of obstructive sleep apnea: | Strongly disagree | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.268# |

| Disagree | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | 7 (7.1%) | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3 (20%) | 3 (11.6%) | 18 (18.2%) | ||

| Agree | 10 (66.6%) | 20 (76.9%) | 55 (55.5%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.7%) | 18 (18.2%) | ||

| I have enough ability to be involved with patients with obstructive sleep apnea: | Strongly disagree | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.008# |

| Disagree | 3 (20%) | 4 (15.4%) | 4 (4%) | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 6 (40%) | 6 (23.1%) | 22 (22.2%) | ||

| Agree | 5 (33.3%) | 14 (53.8%) | 61 (61.7%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.7%) | 12 (12.1%) | ||

| I have enough ability to treat the patients with CPAP: | Strongly disagree | 3 (20%) | 1 (3.8%) | 2 (2%) | 0.291# |

| Disagree | 1 (6.7%) | 6 (23.1%) | 30 (30.3%) | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 5 (33.3%) | 8 (30.8%) | 19 (19.2%) | ||

| Agree | 6 (40%) | 10 (38.5%) | 41 (41.4%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 7 (7.1%) |

#Chi-square test were used

Table 5.

Binary logistic regression of the prediction of acceptable level of the knowledge toward OSAKA and OSAKA-KIDS

| Variable | Acceptable level of OSAKA | Acceptable level of OSAKA-KIDS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio(AOR) | 95%CI:Lower–Upper | P value | Adjusted odds ratio(AOR) | 95%CI:Lower–Upper | P value | |

| Age groups | ||||||

| Under 30 years | Ref | |||||

| Above 30 years | 1.238 | 0.098–15.56 | 0.869 | 2.123 | 0.51–8.72 | 0.29 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Ref | |||||

| Female | 0.354 | 0.055–2.276 | 0.274 | 1.29 | 0.49–3.37 | 0.59 |

| Professional qualification | ||||||

| Junior resident | Ref | |||||

| Senior resident | 5.34 | 0.376–75.76 | 0.216 | 0.19 | 0.04–0.89 | 0.03 |

| Specialist | 5.644 | 0.30–104.47 | 0.245 | 0.22 | 0.04–1.23 | 0.08 |

| Current practice | ||||||

| Ministry of health | Ref | |||||

| Royal medical services | 0.37 | 0.073–1.917 | 0.23 | 1.54 | 0.56–4.24 | 0.4 |

| Private sector | 1.5 | 0.25–8.78 | 0.65 | 1.37 | 0.51–3.65 | 0.52 |

| University hospitals | 0.51 | 0.06–4.14 | 0.53 | 0.96 | 0.25–3.75 | 0.96 |

| Duration of practice | ||||||

| < 5 years | Ref | |||||

| 5–10 years | 0.62 | 0.06–6.38 | 0.695 | 1.7 | 0.62–4.68 | 0.29 |

| > 10 years | 0.09 | 0.01–0.93 | 0.044 | 0.7 | 0.25–1.95 | 0.49 |

| Training in an otolaryngology subspecialty | ||||||

| Yes | Ref | |||||

| No | 3.7 | 0.92–14.8 | 0.065 | 1.934 | 0.89–4.19 | 0.09 |

OSAKA and OSAKA-KIDS Confidence Scores

Many participants either ‘agreed’ (60.8%) or ‘strongly agreed’ (14.3%) they are confident in their ability to identify patients with OSA. Similarly, 57.1% of participants ‘agreed’ and 10% ‘strongly agreed’ they are confident in managing patients with OSA. However, as shown in Table 4, less than half of the participants (46.4%) either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ they are confident in their ability to treat the OSA patients with CPAP. Table 4. shows that the proportion of specialists who ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ they are confident in their ability to manage patients with OSA was significantly higher that junior residents (73.8% vs 33.3%; p = 0.008). Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Data from the attitude part of both OSAKA and OSAKA-KIDS questionnaires

Difference of the Overall Score of the OSAKA and OSAKA-KIDS Between the Subgroups of the Study

Statistically significant differences in OSAKA scores were found between otolaryngologists under 30 years of age and those above, with higher scores for the older age group. Following the same pattern, as shown in Table S1, junior residents had statistically significant lower OSAKA scores compared with senior residents and specialists. Regarding OSAKA-KIDS scores, no statistically significant differences were noted between subgroups.

Acceptable Level of Knowledge Toward OSAKA and OSAKA-KIDS

More than 10 years at practice was associated with statistically significant higher levels of knowledge towards OSAKA scale (AOR = 0.09; p = 0.044) as shown in Table 5. In addition, being a senior resident was significantly associated with more knowledge towards OSAKA-KIDS scale (AOR = 0.19; p = 0.03). No other factors showed statistically significant associations with more knowledge towards OSAKA or OSAKA-KIDS scales.

Discussion

Sleep apnea syndrome (also known as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, or OSAS) is a condition characterized by repeated and uncontrolled breathing interruptions during sleep. They lead to incessant micro-awakenings of which the patient is not aware [23]. It is a highly prevalent sleep-related breathing disorder worldwide and occurs in 1%–5% of children [24]. It is caused by the obstruction of the upper airways, the causes of which can be multiple such as dilation of the pharynx, obstruction of the nasal passages, increase in the size of the tonsils, the tongue, or the uvula. Its management can be complex and multidisciplinary. However, the most encountered problem is its early positive diagnosis [23, 24].

In this study, we aimed to evaluate Jordanian ENT knowledge about OSA, and this was the first study to use the validated OSAKA questionnaire to determine the knowledge, attitudes, and confidence levels of Jordanian ENT physicians on Sleep Apnea. The questionnaire after being pilot tested among 15 participants. The questionnaire was sent and mailed to 417 ENT doctors from whom 140 filled the questionnaire completely. Our research results demonstrated that median knowledge score for all participants was good and satisfying 15 out of 18 with being the lowest score among junior residents and the highest among specialists with no statistically significant gender differences. These findings are similarly found in a Canadian study conducted by Saad and al. where median knowledge score found was 16 out of 18 and similarly, junior residents showed less knowledge than seniors and specialists [25]. But these results were the opposite of results reported by Jokubauskas and al. in a nation-wide study conducted among 353 dentists in Lithuania in 2018 where increased years of experience was significantly associated with less knowledge [26]. Concerning OSAKA-KIDS knowledge scores, our study showed a lower median knowledge score 12 out of 18 with being enlarged tonsils and adenoids the most frequent found contributing factor to OSA 92%. These findings were also strongly concomitant with an Iranian study conducted by Reza and al. However, in contrast to the Iranian study where senior residents had again better knowledge than juniors, in our research, results showed that junior, senior residents and specialists reported almost similar OSAKA-KIDS knowledge scores [27].

As now it was well proven that OSAHS is a serious medical condition [28]. Attitudes toward it were evaluated and results showed that overall, all respondents considered OSA to be a "very important" clinical disorder. This also was concomitant with what was reported from the Canadian study by Saad and Al [26]. However, in our study, the strong involvement of senior residents in OSA management made of their attitude clearly higher than junior residents (81% vs 46.6%; p = 0.008).

Concerning OSA diagnosis, ability self-confidence to identify OSA in patients was found good 75.1% among respondents. Similarly, self confidence in managing patients with OSA was found satisfying 67.1%. Yet concerning self confidence in treating confirmed OSA patients with CPAP, results showed lower percentage 46.4%.

In this study, we demonstrated the significant difference in knowledge and confidence in the management and treatment of Sleep Apnea Syndrome between specialists and senior residents and junior residents in Jordan. The lower knowledge, attitude, self confidence in treatment and care among junior residents is in fact due to the clear lack of their involvement in the overall management of this serious disorder in their junior training years. This factor could have strong negative impact on the condition early diagnosis and effective management. Also, being a complicated condition with multiple causes and different treatment options [29]. Early involvement in its management is a keystone to master it and prevent its dangerous complications, but also contribute to raise awareness of some causes such us overweight and obesity [30].

Its seems that improving junior residents’ knowledge and skills toward Sleep Apnea Syndrome apart from their early including in its multidisciplinary management could be achieved with continuous medical education, seminars, webinars, research improvement, global collaboration, and involvement in international specific networks [31]. Hence, junior residents will be able to show better diagnosis skill for this condition and will present better self confidence in its treatment. Also, appropriate behaviors specifically about OSA will be gained and thus, health promotion will be optimized [31].

Strengths and Limitations

Cross sectional studies are cheap to do and may be finished quickly, but they do not show the true generality among the population being examined and do not show a strong causative relationship. Second, the sample size is quite limited since the data collaborators encountered challenges throughout the data collection. However, our research has some merits, including the fact that it is the first to examine the degree of knowledge of otolaryngology resident physicians in Jordan on OSA, and we attempted to prevent bias as much as possible by engaging an investigator to monitor the data collecting process in order to spot multi-auto answers and irrational replies.

Conclusion

The understanding of OSA among otolaryngology residents and specialists was sufficient. It is crucial to conduct face to face courses for otolaryngology resident doctors by following the most recent guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of OSA in order to further increase the level of knowledge about OSA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

EA and AAT contributed to study conception, study design, data collection, data analysis, write up of original draft of manuscript, and review of manuscript for editorial and intellectual contents. LA, DS, SA-G, MA, SS, AA, MAR, and AAE-S contributed to literature review, data collection, and review of manuscript for editorial and intellectual contents.

Data Availability

All data are available within the manuscript and can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors does not have any conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval of research has been approved on the 4 April 2022 (No.5/6/2021/2022).

Informed Consent

Informed Consent was taken before answering the questionnaire.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:687–698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khassawneh B, Ghazzawi M, Khader Y, et al. Symptoms and risk of obstructive sleep apnea in primary care patients in Jordan. Sleep Breath. 2009;13:227–232. doi: 10.1007/S11325-008-0240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lévy P, Kohler M, McNicholas WT, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015 doi: 10.1038/NRDP.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krysta K, Bratek A, Zawada K, Stepańczak R. Cognitive deficits in adults with obstructive sleep apnea compared to children and adolescents. J Neural Transm. 2017;124:187. doi: 10.1007/S00702-015-1501-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin JM, Agusti A, Villar I, et al. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307:2169. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2012.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terán-Santos J, Jimenez-Gomez A, Cordero-Guevara J. The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traffic accidents. Cooperative Group Burgos-Santander. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:847–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus CL. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: differences between children and adults. Sleep. 2000;23(Suppl 4):S140–S141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ai S, Li Z, Wang S, et al. Blood pressure and childhood obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;65:101663. doi: 10.1016/J.SMRV.2022.101663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteller E, Villatoro JC, Agüero A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and growth failure. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;108:214–218. doi: 10.1016/J.IJPORL.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodges E, Marcus CL, Kim JY, et al. Depressive symptomatology in school-aged children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: incidence, demographic factors, and changes following a randomized controlled trial of adenotonsillectomy. Sleep. 2018 doi: 10.1093/SLEEP/ZSY180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang SJ, Chae KY. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and sequelae. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:863–871. doi: 10.3345/KJP.2010.53.10.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentham J, Di Cesare M, Bilano V, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaiswal S, Owens R, Malhotra A. Raising awareness about sleep disorders. Lung India. 2017;34:262. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.205331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen RC, Zozula R, Jahn EG, Carson JL. Low rates of recognition of sleep disorders in primary care: comparison of a community-based versus clinical academic setting. Sleep Med. 2001;2:47–55. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Khafaji H, Bilgay IB, Tamim H, et al. Knowledge and attitude of primary care physicians towards obstructive sleep apnea in the Middle East and North Africa region. Sleep Breath. 2021;25:579–585. doi: 10.1007/S11325-020-02137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang JWR, Akemokwe FM, Marangu DM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea awareness among primary care physicians in Africa. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:98–106. doi: 10.1513/ANNALSATS.201903-218OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schotland HM, Jeffe DB. Development of the obstructive sleep apnea knowledge and attitudes (OSAKA) questionnaire. Sleep Med. 2003;4:443–450. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(03)00073-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devaraj NK. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding obstructive sleep apnea among primary care physicians. Sleep Breath. 2020;24:1581–1590. doi: 10.1007/S11325-020-02040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ansari S, Hu A. Knowledge and confidence in managing obstructive sleep apnea patients in Canadian otolaryngology-head and neck surgery residents: a cross sectional survey. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:1–9. doi: 10.1186/S40463-020-00417-6/FIGURES/2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erfanian R, Sohrabpour S, Najafi A, et al. Effect of otolaryngology residency program training on obstructive sleep apnea practice. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1007/S12070-021-02718-2/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schotland H. Development of the obstructive sleep apnea knowledge and attitudes (OSAKA) questionnaire. Sleep Med. 2003;4:443–450. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(03)00073-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uong EC, Jeffe DB, Gozal D, et al. Development of a measure of knowledge and attitudes about obstructive sleep apnea in children (OSAKA-KIDS) Archiv Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):181–186. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1389–1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Celestin J, Lockey RF. Pediatric sleep apnea syndrome: an update. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:852–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ansari S, Hu A. Knowledge and confidence in managing obstructive sleep apnea patients in Canadian otolaryngology-head and neck surgery residents: a cross sectional survey. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:21. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00417-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jokubauskas L, Pileičikienė G, Žekonis G, Baltrušaitytė A. Lithuanian dentists’ knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practices regarding obstructive sleep apnea: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Cranio. 2019;37:238–245. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2018.1437006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erfanian R, Sohrabpour S, Najafi A, et al. Effect of otolaryngology residency program training on obstructive sleep apnea practice. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12070-021-02718-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pack AI, Gislason T. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: a perspective and future directions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:434–451. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonsignore MR, Baiamonte P, Mazzuca E, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and comorbidities: a dangerous liaison. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2019;14:8. doi: 10.1186/s40248-019-0172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuomilehto H, Seppä J, Uusitupa M. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea–clinical significance of weight loss. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Castro Correa C, Berretin Felix G. Educational program applied to obstructive sleep apnea. J Commun Dis, Deaf Stud Hearing Aids. 2016 doi: 10.4172/2375-4427.1000160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available within the manuscript and can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.