Abstract

Subtotal petrosectomy (STP) is characterized by obliteration of the middle ear and occlusion of the external auditory canal. The advent of the endoscope has allowed a reduction in morbidity for some conditions such as cholesteatoma and other middle ear disorders, but STP still plays an important role. A retrospective review of medical records and videos of patients who had undergone STP was performed. Perioperative data and images were collected from various clinical cases who had undergone subtotal petrosectomy at our tertiary referral university hospital in Verona. We confronted our experience with a review of the literature to present the main indications for this type of procedure. STP allows a variety of diseases to be managed effectively as it offers the possibility of a definitive healing with radical clearance of temporal bone. Moreover, it can be safely combined with other procedures with a very low complication rate. Although the endoscope represents a revolution in ear surgery, STP, when indicated, is nowadays a surgical option that should be included in the otosurgeon's portfolio.

Keywords: Subtotal petrosectomy, Cholesteatoma, Cochlear implant, Temporal bone fractures, Skull base tumors

Introduction

Subtotal petrosectomy (STP) remains one of the most important surgical procedures for diseases of the middle ear and lateral skull base, although the advent of endoscopic surgery has reduced the use of the microscope in many cases [1–3]. The advent of the endoscope, for example, has allowed a clear view of the structures of the middle ear and the treatment of lesions involving even the temporal bone apex [2]. However, not all temporal bone lesions can be radically treated with the endoscope, and sometimes the microscopic approach is required [5]. We can still consider petrosectomy as a workhorse, as it is useful in many situations. In the last decade, there has been an increased interest in STP, which is also confirmed in the literature. In this procedure, the middle ear and mastoid are obliterated and the external auditory canal (EAC) is closed. STP is usually performed for recurrent or life-threatening infections and temporal bone diseases [4]. In these clinical conditions, there is usually no realistic chance of reconstructing the air conduction pathways of the auditory system. Therefore, complete removal of all temporal bone pneumatic cells (including retrofacial, retrosigmoidal, antral, retrolabyrinthine, supralabyrinthine, infralabyrinthine, peritubal, and pericarotid cells) is the main feature of STP, and the degree of bone removal should be tailored to the extent of the disease [5]. Obliteration of the middle ear results in severe conductive hearing loss. For this reason, the procedure is often reserved for patients with poor hearing function or in cases where no other solution is possible due to the severity of the condition that threatens the patient's safety, such as a large tegmental defect that is difficult to repair with other techniques [6, 7]. According to a review of the literature, STP has been associated with any middle ear procedure in which blind sac closure of the external auditory canal was performed. Even extended skull base procedures (transotic, transcochlear, and infratemporal approaches, as well as temporal bone resections, other skull base procedures for middle and posterior fossa tumors, and surgery for parotid gland disease) were sometimes referred to as STP [8–11]. This can lead to some confusion in the literature. Therefore, the basic steps of this procedure, which is performed at our institution, are described below. The aim of this paper is to give a pictorial overview and to present our experience, indications and limitations of subtotal petrosectomy, emphasizing that even in our institution, where endoscopic ear surgery is performed whenever possible, STP is a basic fundamental technique that can be combined with other procedures to treat various diseases.

Materials and Methods

A pictorial review of patients that underwent STP in our Department from 2014 to 2022 was performed, including cases according to the literature description of the procedure. A brief description of the main features of each clinical case is given below each paragraph.

Surgical Procedure

The main steps of the procedure are: (1) blind sac closure of the external auditory canal (EAC); (2) exenteration of the middle ear and mastoid, including the perisigmoidal, perilabyrinthine, perifacial, and hypotympanic cells; (3) removal of the epithelium and mucosa of the middle ear; (4) closure of the tympanic opening of the Eustachian tube; (5) and obliteration of the cavity with abdominal fat (Fig. 1a–d). We would like to emphasize that the closure of the EAC and the obliteration of the cavity are two basic steps that must be performed perfectly:

closure of the EAC, if not performed correctly, can lead to various complications such as cavity infections and cholesteatoma; it also eliminates the need for lifelong cavity care and water avoidance [12]

various materials have been used to obliterate the cavity and Eustachian tube, but we still prefer autologous fat grafts and temporalis muscle flaps, which are the most commonly used in the literature [13–18].

Fig. 1.

a, b EAC eversion and “blind sac closure”; c postoperative view with completely drilled air cells; d obliteration of the cavity with abdominal fat and closure of the Eustachian tube (ET) with a fragment of the temporal muscle

Before surgery, all patients signed an informed consent form, which was adapted for STP and for other surgical procedures if they were associated with surgery. During surgery, the facial nerve was monitored with a neural integrity monitor (NIM Pulse® 3.0; Medtronic). Surgery began with a wide postauricular S-shaped incision that provided access from the temporalis muscle to the jugular foramen. The skin and subcutaneous tissue were elevated from the temporalis muscle. A mastoidectomy was then performed, and the sigmoid sinus, middle fossa dura, and sinodural angle were exposed. The sigmoid sinus was traced to the jugular bulb. The mastoid was drilled using a canal-wall-down technique until the apex of the petrous bone was reached, at which time the semicircular canals were identified and preserved. The facial nerve was identified at the second genu and traced to the stylomastoid foramen. Finally, the vertical segment of the facial nerve was drilled circumferentially, leaving the facial nerve securely enclosed in the bone. During canal-wall-down mastoidectomy, all visible cell tracts were removed eccentrically, but the otic capsule, facial nerve canal, and dural plates were spared. It is important that all mastoid cells are drilled and no mucosa is left behind, as this can potentially form a mucocele. The eustachian tube was obliterated with a fragment of temporal muscle and fixed with bone wax or fibrin glue. An autologous abdominal fat graft was used along with absorbable material (Tabotamp®) and fibrin glue to obliterate the cavity. Finally, the EAC was closed watertight, the muscle and skin were sutured in layers, and a compression bandage was applied. This procedure can be combined with other procedures, depending on the patient's condition or surgical program (see indications beyond).

Indications

In our case series, we performed subtotal petrosectomy for the treatment of various diseases (Table 1). We will list the main indications and evidence in the literature for each disease in each paragraph.

Table 1.

Main indications for subtotal petrosectomy

| Chronic otitis media and middle ear cholesteatoma | As a last resort, when there is no chance of rehabilitation of the ear or in dangerous situations such as large tegmental defects or perylimphatic fistulas |

| Tegmen defects and meningoencephalic herniation repair | If the defect is too large, the herniation is too severe, or the defect is too medial and no other techniques are applicable |

| Facial nerve decompression surgery | When the second and third tracts of the facial nerve need to be decompressed, as this provides excellent exposure of the nerve |

| Middle ear lesions | To overcome difficult surgical conditions, such as cochlear fistula, insufficient exposure of tumor margins, or excessive bleeding |

| Difficult cochlear implants (CI) or active middle ear implants (AMEI) in case of altered ear anatomy or malformations | To get a better control over the area of the round window to facilitate a correct and complete insertion of the array |

| Malignancies of the ear and the parotid gland | As a step in conjunction with other procedures to achieve radical exeresis of the lesion |

Chronic Otitis Media and Cholesteatoma

STP may be seen as a last resort for chronic otitis media and cholesteatoma because of its invasiveness. In some cases, when even canal-wall-down (CWD) mastoidectomy does not result in complete eradication of the disease, a more invasive procedure with complete exenteration of all air cells with obliteration of the middle ear and mastoid and closure of the external auditory canal (EAC) is required. In recent years, this procedure is gaining interest due to increasing evidence that the recurrence rate of cholesteatoma in operated ears with STP is very low [19]. In our institute, we perform STP for chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma when there is multiple recurrence and no realistic chance of reconstructing the conductive apparatus of the ear, or when surgery is performed on a deaf ear. It is appropriate when the cholesteatoma leaves a large surgical cavity exposing vital structures such as the dura, carotid artery, or sigmoid sinus. Obliteration of the middle ear can be extremely safe if removal of a cholesteatoma opens fistulas that cause inner ear or cerebrospinal fluid leaks. However, even though the recurrence rate is low when the procedure is performed correctly, it is not zero.

Clinical Case

A 15-year-old with a history of chronic left otitis media with cholesteatoma. He had undergone tympanoplasty (TPL) with mastoidectomy 2 years previously. Audiological examination revealed severe sensorineural hearing loss. The preoperative CT image is shown in Fig. 2: axial view (a) and coronal view (b) with hypodense material in the left tympanic cavity and left mastoid cells; erosion of the left tegmen tympani. Given the hearing status and extent of the cholesteatoma, we performed a subtotal left petrosectomy. Figure 2c shows the cholesteatoma occupying the mastoid, while Fig. 2d shows the large defect that remains after removal of the cholesteatoma. In this case, STP allowed us to create a safe cavity isolated from the external environment.

Fig. 2.

a, b Preoperative CT scan: axial view and coronal view with hypodense material in the left tympanic cavity and in the left mastoid cells; erosion of the left tegmen tympani is clearly seen (*); c intraoperative view: mastoid cholesteatoma; d intraoperative view: complete drilling of the air cells including the retrofacial; no evidence of residual cholesteatoma; a large tegmental defect is visible (*)

Tegmen Defects and Meningoencefalic Herniation Repair

Temporal bone defects may be congenital or acquired. The latter are usually the result of either trauma, ear disease, or surgery [20–22]. Although traumatic temporal bone defects respond to conservative treatment [23], such defects remain a potential route for ascending infections because healing in the temporal bone is fibrous. The development of meningoencephalic herniation or meningitis at a later stage may therefore require surgical intervention [16, 17, 24]. There are no guidelines for the treatment of temporal bone defects. Most surgeons rely on their personal experience. Various surgical techniques have been described over time [20, 25, 26]: Sanna et al. [20] described subtotal petrosectomy with middle ear obliteration and cul-de-sac closure of the external auditory canal to achieve secure closure of the skull base. The choice of surgical technique depends on the size and location of the bone defect, residual hearing, and coexisting diseases in the ear. Surgical treatment options include the transmastoid, middle fossa, or a combination of both. Our preference is based on the size and location of the defect and the potential for rehabilitation of the ear. Whenever possible, a minicraniotomy is the better option because it is less invasive, allowing the graft to be inserted from above without retracting the temporal lobe [27, 28]. However, if the defect is too large, the herniation is too severe, or the defect is too medial and the ear cannot be spared, as temporal bone trauma can cause deep SNHL in up to 8% of cases [29], we successfully use subtotal petrosectomy to isolate the ear.

Clinical Case

A 45-year-old woman developed left facial palsy grade II (H-B scale) after bilateral chronic otitis media. She had a history of acute myeloid leukemia. The preoperative CT scan is shown in Fig. 3a, b. Audiological examination revealed severe sensorineural hearing loss on the left side. Given the hearing status, tegmen tympani dehiscence, and immunodeficiency status, we performed a left subtotal petrosectomy. Figure 3c shows an intraoperative view with a large tegmen tympani dehiscence, and Fig. 3d shows a postoperative MRI.

Fig. 3.

a CT scan, axial, right ear: a giant cholesteatoma occupies the middle ear and erodes the surrounding structures. A CSL fistula can be seen; b preoperative CT scan: axial view with left tegmen tympani dehiscence (arrow); c intraoperative view: large left tegmen tympani and mastoideum dehiscence; d post-operative MRI: left petrosectomy with abdominal fat in neo-cavity (*)

Facial Nerve Decompression Surgery

Paralysis of the facial nerve can have many causes. The most common cause is idiopathic (Bell's palsy) and the second most common is trauma to the temporal bone [30]. There may also be iatrogenic injury to the facial nerve during ear surgery. Facial nerve palsy may occur in 10% of temporal bone fractures, and these fractures are most common in motor vehicle accidents [31]. Eighty percent of fractures are longitudinal; facial paralysis occurs in 20% of these. Transverse fractures account for 20% of all fractures; paralysis occurs in 50% of them [32]. Various approaches to decompression of the facial nerve have been described in the literature, depending on the site of compression and the associated hearing status [33]. Although some advocate surgical decompression of the facial nerve via a middle fossa approach even for severe idiopathic facial nerve palsies, in which early motor nerve conduction studies show facial nerve degeneration of at least 90% in the first 3–14 days after symptom onset [34], this approach is not recommended because of the invasiveness of the procedure, which may cause more harm than good [35–37]. Similarly, delayed facial nerve palsy occurs more than 1 day after injury and typically reflects swelling of the nerve in its bony canal. It is primarily treated with medications, including intravenous glucocorticoid therapy [38]. In contrast, immediate facial nerve palsy following middle ear or head injury requires urgent consultation with an otolaryngologist and usually surgical intervention [38–40]. Minimally invasive transcanal endoscopic decompression of the facial nerve is often sufficient when the area to be treated is limited to the geniculate ganglion [3]. Choice of technique depends on the type of the temporal bone fracture, the status of the ossicular chain, and the nature of the facial nerve impairment. Endoscopic decompression of the facial nerve results in earlier recovery, less postoperative pain, and better postoperative closure of the air–bone gap compared with the conventional microscopic technique. When all of the second and third facial nerve tracts need to be decompressed, the transmastoid route, and STP in particular, provides excellent exposure of the nerve. This is the preferred method, especially when the trauma causes a deaf ear on the side of the palsy. When decompression of the facial nerve is considered, STP is considered for lesions of the tympanic and mastoid portions of the facial nerve. When the first tract in the internal auditory canal must be reached to decompress the nerve or treat lesions such as neurinomas, STP is not sufficient because more invasive procedures such as transcochlear, translabyrinthine, or middle fossa (MCF) approaches are required at this site [41].

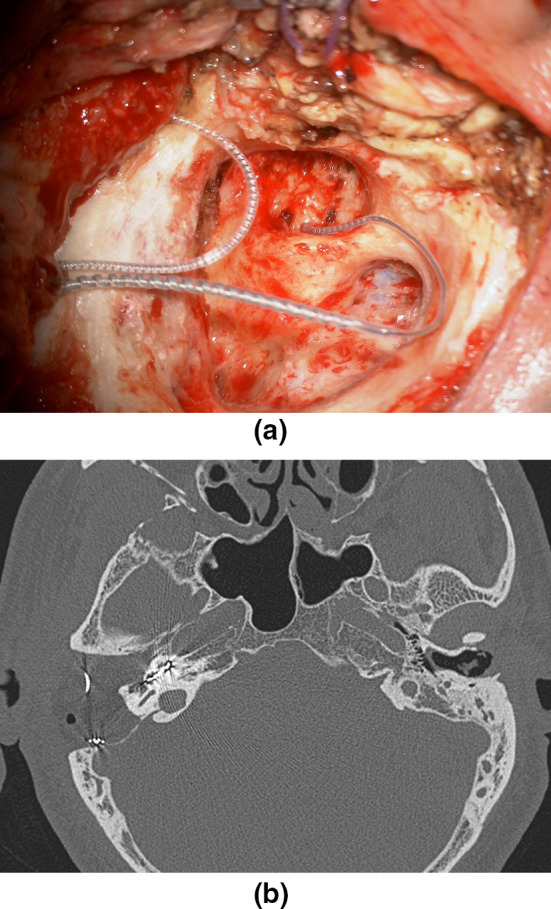

Clinical Case

A 46-year-old man developed right grade V facial palsy (H-B scale) after head trauma resulting from an accidental fall down stairs. Audiologic examination revealed complete hearing loss on the right side, normal hearing function on the left side. The preoperative CT scan is shown in Fig. 4a. Figure 4b, c show an intraoperative view: decompression of the face with epineurium section from the geniculate ganglion to the stylomastoid foramen. In this particular case, given that the trauma caused the deaf ear on this side, we opted for a partial labyrinthectomy (drilling the lateral semicircular canal) to completely decompress the second genu of the facial nerve. We also suggested the cochlear implant to the patient, but the patient refused it.

Fig. 4.

a Preoperative CT scan: right temporal bone fracture witch cross toward the vestibule; b, c intraoperative view: facial decompression with epineurium section from the geniculate ganglion to the stylomastoid foramen. In this particular case, given the fact the trauma caused the deaf ear of this side, we chose to perform a partial labyrinthectomy (drilling of lateral semicircular canal) to decompress full the second genu of the facial nerve

Middle Ear Lesions (Paragangliomas)

Subtotal petrosectomy is a widely used technique to treat middle ear lesions, which are rare. The most common are temporal bone paragangliomas, benign but locally aggressive tumors that arise at various sites on the temporal bone. There are two types: tympanomastoid paragangliomas, commonly known as 'glomus tympanicum', which are tumors originating from the glomus bodies along the Jacobson and Arnold nerves, and tympanojugular paragangliomas or 'glomus jugulare', which originate from the paraganglia in the adventitia of the dome of the bulbus jugularis or originate from the hypotympanum and invade secondarily into the bulbus jugularis [42]. The most widely used classification is that proposed by Fisch and Mattox [43], which classifies tumors based on their extension. Surgery is the best treatment option for TMPs because it offers complete tumor removal and low recurrence and complication rates. In our experience, we prefer minimally invasive endoscopic techniques whenever possible for early-stage tumors because the recurrence rate is low and hearing can be preserved. However, patients with tumors that have invaded the mastoid are best treated with STP in our series because of difficult surgical conditions, such as cochlear fistula, inadequate exposure of tumor margins, or bleeding. Considering that hearing is often impaired in advanced lesions, Sanna et al. [44] have shown that even with STP, hearing loss before and after surgery is minimal and acceptable.

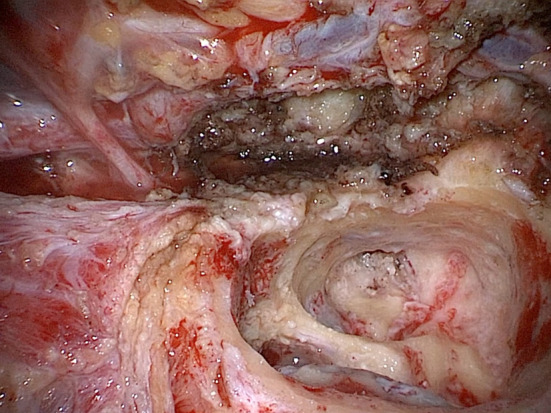

Clinical Case

A 49-year-old man suffering from tinnitus and mixed profound hearing loss on the left side presented to us. Otoscopy revealed a red middle ear lesion with an intact MT, suggestive of paraganglioma. The preoperative CT scan is shown in Fig. 5a. The patient underwent angiography (Fig. 5b), which showed contrast blush at the level of the lower part of the left mastoid bone, suggestive of a tympanic effusion. Given the severe vascularization of the lesion and its excessive bleeding, we performed a subtotal left petrosectomy to completely remove the lesion (Fig. 5c, d show an intraoperative view).

Fig. 5.

a Preoperative CT scan: axial view with ipodense material in the left middle ear and mastoid cells; b maxillary artery angiography: contrast blush(*) at the level of the inferior part of the left mastoid bone, compatible with tympanic glomus, is documented; c, d intraoperative view: the highly vascularization of the paraganglioma and its subsequent bleeding during dissection worsen the visualization of the anatomical landmarks

Difficult Cochlear Implant (CI) or Active Middle Ear Implant (AMEI) Procedures in Ear Malformations

Although cochlear implantation is considered a standard procedure, it can be challenging in several complex situations, such as concurrent chronic otitis media with or without cholesteatoma, previous surgery, malformations of the inner ear with risk of CSF leakage, and other [16, 17, 45–47]. Since 1998, when Issing et al. and Bendet et al. [7, 14] proposed STP as a useful technique for cochlear implantation in ears with chronic otitis media (COM), it has been gradually applied to a variety of difficult situations in CI surgery [16, 17, 45–47]. Placement of an electrode in a potentially infected area carries the risk of meningitis and recurrent skin infections over the implant due to biofilm formation. STP simultaneously allows eradication of the disease, prevention of recurrence, prevention of meningitis, and safe placement of the cochlear implant electrode, which are the goals of the surgery [19]. Moreover, in recent years, the scientific literature has increasingly demonstrated the efficacy of STP in combination with cochlear implantation in patients with severe ossification/obliteration of the cochlea, malformations of the inner ear with high risk of CSF leakage, temporal bone fractures involving the inner ear, and unfavourable anatomical conditions [7, 14, 16, 17, 48, 49]. Complete control of all landmarks allows safer surgical maneuvers. In particular, better control of the round window area can increase the possibility of correct and complete array insertion even in complex cases [19, 49] (Fig. 6a, b). In addition, STP allows complete isolation of the surgical cavity from the external environment by closing the Eustachian tube opening and the EAC, reducing the risk of postoperative infection, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, and meningitis [50, 51] and eliminating the need for lifelong cavity maintenance. The focus should be on malformations of the inner ear and unfavourable anatomic conditions, in which STP plays a key role in our experience. Many authors advocate the use of STP to improve CI safety [16, 52, 53] to manage abnormal morphology, complicated electrode insertion, high risk of developing postoperative CSF leak/meningitis, and inconsistent facial nerve (FN) course. In a meta-analysis, Farhood et al. [54] found that malformations of the inner ear had a higher rate of Gusher (39.1%) and facial nerve anomalies (34.4%). In structurally complex cases, including those with vascular/nerve variations such as a very anterior sigmoid sinus, a high bulb jugularis, and with FN or internal carotid artery (ICA) anomalies, access to the round window via the facial recess (with classic posterior tympanotomy) may be dangerous or even impossible.

Fig. 6.

a Intraoperative view after right CI placement. Removal of the posterior wall of the EAC improves visualization of the round window in difficult anatomical conditions; b postoperative CT scan: the array is correctly placed in the right cochlea; complete air cells drilling with ipodense material in the neo-cavity (abdominal fat)

Clinical Case

A 4-year-old child treated with amikacin at birth due to inhalation of meconium. He was affected by psychomotor retardation. Audiological examination revealed bilateral severe sensorineural hearing loss. He was brought to us after his hearing worsened. Even with hearing aids, his hearing was poor. Preoperatively, the CT showed incomplete partition type 3, in which the fundus of the internal auditory canal communicates with the basal turn of the cochlea and is not separated by bone (Fig. 7a). We decided to perform cochlear implantation with a subtotal petrosectomy because the risk of gusher was too high and to better control the insertion of the array (Fig. 7b, c: intraoperative view). Figure 7d shows a postoperative CT scan with correctly placed array in the left cochlea.

Fig. 7.

a Preoperative CT scan: the left IAC has a tapered scape and incomplete partition type 3. Note the fundus of the internal auditory canal, which communicates with the basal turn of the cochlea and is not separated by bone (arrow). In this extreme case, we performed an STP because the risk of gusher was too high and to better control the insertion of the array; b, c intraoperative view: the array is inserted; in this extreme case the cochlea was partially drilled (infrapromontorial approach) to visualize the basal turn of the cochlea and to ensure that it is not inserted into the internal auditory canal by dehiscence of the medial wall of the cochlea; d postoperative CT scan: the array is correctly placed in the left cochlea; complete air cells drilling with ipodense material in the neo-cavity (*)

Malignancies of the Ear and the Parotid

Although some authors do not consider these procedures equivalent, we usually perform STP in conjunction with other procedures to achieve radical exeresis of larger lesions such as malignant tumors of the skin of the EAC or temporal region or the parotid gland invading the ear. Treatment of malignant salivary gland tumors remains primarily surgical [55, 56]. For limited tumors, surgical treatment is well defined and based on parotidectomy with preservation of the facial nerve when possible [57]. However, advanced neoplasms present a surgical challenge because inadequate tumor resection in these anatomically complex regions leads to local recurrence of disease at the lateral skull base. The indication for resection of the temporal bone is not uniform. For malignant tumors, a lateral temporal bone resection, which may also be referred to as a partial petrosectomy, is usually performed as the minimal possible resection to eliminate the disease. More aggressive procedures may also be referred to as subtotal petrosectomy, as described by Fisch et al. [43], which may be tailored in the surgical treatment of parotid malignancies with skull base involvement. Subtotal petrosectomy ensures a good view of the facial nerve and its management by preserving safe oncologic margins and allowing identification and preservation of the facial nerve or facilitating reconstruction with a nerve graft when there is no chance of preservation for oncologic reasons. When circumferential growth of parotid neoplasms involves the floor of the middle cranial fossa and the neurovascular structures of the foramen jugulare [58] or the otic capsule, more invasive temporal bone procedures are required, such as total temporal bone resections or infratemporal fossa procedures. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the temporal bone arising from the external auditory canal or middle ear is rare [59]. Given the low incidence, it is difficult to make evidence-based recommendations for treatment because studies have such small samples [60, 61]. Skin and parotid gland cancers that have invaded the temporal bone are more than 10 times more common, but there is even less evidence on which technique is best [62]. Regardless of the origin of the primary cancer, resection remains the treatment of choice [63]. Prasad and Janecka [64] reported that patients with disease that spread to the middle ear had better 5-year survival with subtotal resection than with lateral petrosectomy or simple mastoidectomy.

Clinical Case

A 72-year-old man came to us for hearing loss and otalgia. He underwent a CT scan, which revealed a lesion in the left temporal mandibular region. Histologic examination performed prior to surgery revealed only chronic inflammation. One week before surgery, he developed facial palsy with grade III (H-B scale). We decided to perform a partial left parotidectomy, subtotal petrosectomy with cochlear implantation to completely remove the lesion, which then turned out to be a squamocellular carcinoma of the temporal bone. Considering the severe bilateral hearing loss and the fact that the ear affected by the tumor was the better ear, we proposed to perform a cochlear implant at the same time. Figure 8 shows an intraoperative view.

Fig. 8.

Intraoperative view: petrosectomy for a malignancy of the EAC; the facial nerve is seen from the geniculate ganglion to its entrance in the parotid gland

Conclusion

Although the role of endoscopic ear surgery is gradually increasing and it is receiving more and more indications [65], microscopic ear surgery cannot be completely replaced. STP is an effective surgical technique that provides good treatment for a wide range of diseases, as it offers the possibility of eliminating the disease by radical removal. This procedure provides excellent exposure, allows obliteration of the middle ear, and can be safely combined with other procedures, such as CI, that can overcome hearing loss. Morbidity is low, especially for the facial nerve, confirming the high reliability of STP. In the treatment of cholesteatoma of the middle ear and mastoid, recurrence rates are low, but we would like to emphasize that they are not zero, so patients must be followed up in any case (Fig. 9a, b).

Fig. 9.

a, b Even after STP, recurrence may occur. In this MRI image, coronal planes, we see the left middle ear filled with fat and a hypointense round lesion. This was confirmed as a cholesteatoma in the DWI sequences

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for any procedure involving the patients mentioned in the study.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marchioni D, Gazzini L, De Rossi S, Di Maro F, Sacchetto L, Carner M, Bianconi L. The management of tympanic membrane perforation with endoscopic type I tympanoplasty. Otol Neurotol. 2020;41(2):214–221. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchioni D, Gazzini L, Bonali M, Bisi N, Presutti L, Rubini A. Role of endoscopy in lateral skull base approaches to the petrous apex. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(3):727–733. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchioni D, Rubini A, Nogueira JF, Isaacson B, Presutti L. Transcanal endoscopic approach to lesions of the suprageniculate ganglion fossa. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coker NJ, Jenkins HA, Fisch U. Obliteration of the middle ear and mastoid cleft in subtotal petrosectomy: indications, technique, and results. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1986;95(1 Pt 1):5–11. doi: 10.1177/000348948609500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisch U. Microsurgery of the skull base. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartels LJ, Sheehy JL. Total obliteration of the mastoid, middle ear, and external auditory canal. A review of 27 cases. Laryngoscope. 1981;91(7):1100-8. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendet E, Cerenko D, Linder TE, Fisch U. Cochlear implantation after subtotal petrosectomies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;255(4):169–174. doi: 10.1007/s004050050037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bibas AG, Ward V, Gleeson MJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(11):1156–1161. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107001338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Cuadrado I, Lassaletta L, Royo A, Cerdeño V, Roda JM, Gavilán J. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome after lateral skull base surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(5):838–840. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31821f1b95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eze N, Huber A, Schuknecht B. De novo development and progression of endolymphatic sac tumour in von hippel-lindau disease: an observational study and literature review. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2013;74(5):259–265. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1347900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuknecht HF, Chandler JR. Surgical obliteration of the tympanomastoid compartment and external auditory canal. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93(6 Pt 1):641–645. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postelmans JT, Stokroos RJ, Linmans JJ, Kremer B. Cochlear implantation in patients with chronic otitis media: 7 years' experience in Maastricht. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266(8):1159–1165. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray RF, Irving RM. Cochlear implants in chronic suppurative otitis media. Am J Otol. 1995;16(5):682–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issing PR, Schönermark MP, Winkelmann S, Kempf HG, Ernst A. Cochlear implantation in patients with chronic otitis: indications for subtotal petrosectomy and obliteration of the middle ear. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(3):127–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barañano CF, Kopelovich JC, Dunn CC, Gantz BJ, Hansen MR. Subtotal petrosectomy and mastoid obliteration in adult and pediatric cochlear implant recipients. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(9):1656–1659. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182a006b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Free RH, Falcioni M, Di Trapani G, Giannuzzi AL, Russo A, Sanna M. The role of subtotal petrosectomy in cochlear implant surgery–a report of 32 cases and review on indications. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(6):1033–1040. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318289841b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernardeschi D, Nguyen Y, Smail M, Bouccara D, Meyer B, Ferrary E, Sterkers O, Mosnier I. Middle ear and mastoid obliteration for cochlear implant in adults: indications and anatomical results. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(4):604–609. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altuna X, García L, Martínez Z, de Pinedo MF. The role of subtotal petrosectomy in cochlear implant recipients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(12):4149–4153. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad SC, Roustan V, Piras G, Caruso A, Lauda L, Sanna M. Subtotal petrosectomy: surgical technique, indications, outcomes, and comprehensive review of literature. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(12):2833–2842. doi: 10.1002/lary.26533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanna M, Fois P, Russo A, Falcioni M. Management of meningoencephalic herniation of the temporal bone: personal experience and literature review. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(8):1579–1585. doi: 10.1002/lary.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wootten CT, Kaylie DM, Warren FM, Jackson CG. Management of brain herniation and cerebrospinal fluid leak in revision chronic ear surgery. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(7):1256–1261. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000165455.20118.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rafferty MA, Mc Conn Walsh R, Walsh MA. A comparison of temporal bone fracture classification systems. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(4):287–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savva A, Taylor MJ, Beatty CW. Management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks involving the temporal bone: report on 92 patients. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(1):50–56. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamerer DB, Caparosa RJ. Temporal bone encephalocele–diagnosis and treatment. Laryngoscope. 1982;92(8 Pt 1):878–882. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasscock ME, 3rd, Dickins JR, Jackson CG, Wiet RJ, Feenstra L. Surgical management of brain tissue herniation into the middle ear and mastoid. Laryngoscope. 1979;89(11):1743–1754. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson CG, Pappas DG, Jr, Manolidis S, Glasscock ME, 3rd, Von Doersten PG, Hampf CR, Williams JB, Storper IS. Brain herniation into the middle ear and mastoid: concepts in diagnosis and surgical management. Am J Otol. 1997;18(2):198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feenstra L, Sanna M, Zini C, Gamoletti R, Delogu P. Surgical treatment of brain herniation into the middle ear and mastoid. Am J Otol. 1985;6(4):311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adkins WY, Osguthorpe JD. Mini-craniotomy for management of CSF otorrhea from tegmen defects. Laryngoscope. 1983;93(8):1038–1040. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khwaja S, Mawman D, Nichani J, Bruce I, Green K, Lloyd S. Cochlear implantation in patients profoundly deafened after head injury. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(8):1328–1332. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182659d19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owusu JA, Stewart CM, Boahene K. Facial nerve paralysis. Med Clin N Am. 2018;102(6):1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vajpayee D, Mallick A, Mishra AK. Post temporal bone fracture facial paralysis: strategies in decision making and analysis of efficacy of surgical treatment. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;70(4):566–571. doi: 10.1007/s12070-018-1371-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irugu DVK, Singh A, Ch S, Panuganti A, Acharya A, Varma H, Thota R, Falcioni M, Reddy S. Comparison between early and delayed facial nerve decompression in traumatic facial nerve paralysis—a retrospective study. Codas. 2018;30(1):e20170063. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20182017063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das A, Janweja M, Mitra S, Hazra S, Sengupta A. Endoscopic versus microscopic facial nerve decompression for traumatic facial nerve palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280(7):3187–3194. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-07836-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gantz BJ, Rubinstein JT, Gidley P, Woodworth GG. Surgical management of Bell's palsy. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(8):1177–1188. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, Schwartz SR, Drumheller CM, Burkholder R, Deckard NA, Dawson C, Driscoll C, Gillespie MB, Gurgel RK, Halperin J, Khalid AN, Kumar KA, Micco A, Munsell D, Rosenbaum S, Vaughan W. Clinical practice guideline: Bell's palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(3 Suppl):S1–27. doi: 10.1177/0194599813505967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: steroids, acyclovir, and surgery for Bell's palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(7):830–836. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAllister K, Walker D, Donnan PT, Swan I. Surgical interventions for the early management of Bell's palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD007468. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007468.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodie HA, Thompson TC. Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures. Am J Otol. 1997;18(2):188–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iloreta AM, Malkin BD. Facial nerve paralysis following transtympanic penetrating middle ear trauma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90(11):510–514. doi: 10.1177/014556131109001102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans AK, Licameli G, Brietzke S, Whittemore K, Kenna M. Pediatric facial nerve paralysis: patients, management and outcomes. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(11):1521–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benecke JE., Jr Facial paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2002;35(2):357–365. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanna M, Fois P, Pasanisi E, Russo A, Bacciu A. Middle ear and mastoid glomus tumors (glomus tympanicum): an algorithm for the surgical management. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37(6):661–668. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisch U, Mattox D. Paragangliomas of the temporal bone Micro-surgery of the skull base. Stuttgart, New York: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1988. pp. 148–281. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patnaik U, Prasad SC, Medina M, Al-Qahtani M, D'Orazio F, Falcioni M, Piccirillo E, Russo A, Sanna M. Long term surgical and hearing outcomes in the management of tympanomastoid paragangliomas. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36(3):382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasanisi E, Vincenti V, Bacciu A, Guida M, Berghenti T, Barbot A, Zini C, Bacciu S. Multichannel cochlear implantation in radical mastoidectomy cavities. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127(5):432–436. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.129822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunter JB, O'Connell BP, Wanna GB. Systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical complications following cochlear implantation in canal wall down mastoid cavities. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(4):555–563. doi: 10.1177/0194599816651239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanna M, Dispenza F, Flanagan S, De Stefano A, Falcioni M. Management of chronic otitis by middle ear obliteration with blind sac closure of the external auditory canal. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29(1):19–22. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31815dbb40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vashishth A, Fulcheri A, Prasad SC, Bassi M, Rossi G, Caruso A, Sanna M. Cochlear implantation in cochlear ossification: retrospective review of etiologies, surgical considerations, and auditory outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(1):17–28. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polo R, Del Mar MM, Arístegui M, Lassaletta L, Gutierrez A, Aránguez G, Prasad SC, Alonso A, Gavilán J, Sanna M. Subtotal petrosectomy for cochlear implantation: lessons learned after 110 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(6):485–494. doi: 10.1177/0003489415620427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merkus P, Free RH, Mylanus EA, Stokroos R, Metselaar M, van Spronsen E, Grolman W, Frijns JH, 4th Consensus in Auditory Implants Meeting Dutch Cochlear Implant Group (CI-ON) consensus protocol on postmeningitis hearing evaluation and treatment. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(8):1281–1286. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181f1fc58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vincenti V, Pasanisi E, Bacciu A, Bacciu S. Long-term results of external auditory canal closure and mastoid obliteration in cochlear implantation after radical mastoidectomy: a clinical and radiological study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(8):2127–2130. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colletti V, Fiorino FG, Carner M, Pacini L. Basal turn cochleostomy via the middle fossa route for cochlear implant insertion. Am J Otol. 1998;19(6):778–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szymański M, Ataide A, Linder T. The use of subtotal petrosectomy in cochlear implant candidates with chronic otitis media. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(2):363–370. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farhood Z, Nguyen SA, Miller SC, Holcomb MA, Meyer TA, Rizk HG. Cochlear implantation in inner ear malformations: systematic review of speech perception outcomes and intraoperative findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(5):783–793. doi: 10.1177/0194599817696502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Homer L, Potter BE. Management and outcome of patients with malignant salivary gland tumors. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(7):917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagliati M, Bolner A, Vanoni V, Tomio L, Lay G, Murtas R, Deidda MA, Madeddu A, Delmastro E, Verna R, Gabriele P, Amichetti M. Surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of malignant parotid tumors: a retrospective multicenter study. Tumori. 2009;95(4):442–448. doi: 10.1177/030089160909500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papadogeorgakis N, Goutzanis L, Petsinis V, Alexandridis C. Management of malignant parotid tumors. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;16(1):29–34. doi: 10.1007/s10006-010-0259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leonetti JP, Smith PG, Anand VK, Kletzker GR, Hartman JM. Subtotal petrosectomy in the management of advanced parotid neoplasms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108(3):270–276. doi: 10.1177/019459989310800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moody SA, Hirsch BE, Myers EN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: an evaluation of a staging system. Am J Otol. 2000;21(4):582–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lustig LR, Jackler RK, Lanser MJ. Radiation-induced tumors of thetemporal bone. Am J Otol. 1997;18:230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moffat DA, Grey P, Ballagh RH, Hardy DG. Extended temporal bone resection for squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116(6):617–623. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simo R, Homer J, Clarke P, Mackenzie K, Paleri V, Pracy P, Roland N. Follow-up after treatment for head and neck cancer: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(S2):S208–S211. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116000645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moffat DA, Wagstaff SA. Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11(2):107–111. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prasad S, Janecka IP. Efficacy of surgical treatments for squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: a literature review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;110(3):270–280. doi: 10.1177/019459989411000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marchioni D, Bonali M, Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Rubini A, Pavesi G, Presutti L. Combined approach for tegmen defects repair in patients with cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea or herniations: our experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2014;75(4):279–287. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]