Abstract

One of the crucial triggers of allergic diseases is an inflammatory reaction and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is one of the systemic inflammation biomarkers. Our review aimed to evaluate role of NLR in predicting severity and comorbidities of allergic rhinitis (AR). We systematically searched Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed to find relevant studies. Standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported. Due to the high levels of heterogeneity, the random-effects model was used to generate pooled effects. Eleven articles were included in the systematic review, among which ten were included in meta-analysis including 1122 healthy controls and 1423 patients with AR. We found that patients with AR had a significantly higher level of NLR than healthy controls (SMD = 0.19, 95%CI = 0.03–0.36, P = 0.03). In addition, patients with moderate to severe AR had significantly higher levels of NLR compared to those with mild AR (SMD = 0.41, 95%CI = 0.20–0.63, P < 0.001). Interestingly, it was found that NLR could associate with some comorbidities of AR, like asthma. Our results confirmed that NLR could assist clinicians in predicting the severity and comorbidities of AR.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12070-023-04148-8.

Keywords: Allergic rhinitis, Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, NLR, Meta-analysis

Introduction

About 15–25% of people globally suffer from allergic rhinitis (AR) [1]. Nasal congestion, runny nose, sneezing, and itching are all symptoms of AR. AR, a heterogeneous illness, is an IgE-mediated immunologic response to aeroallergens that causes systemic and localized nasal inflammation [2]. Exposure to outdoor or indoor allergens can sensitize patients suffering from AR [3]. Although AR is not a life-threatening illness, it can impair daily routine life by reducing the quality of life, decreasing sleep quality, and negatively affecting patients’ performance at work.

There is a link between AR and systemic inflammation, as demonstrated in prior studies [4]. Also, NLR can be a crucial sign of systemic inflammation and can be easily measured by taking a patient’s blood sample [5–7]. According to previous investigations, several human illnesses have been linked to increased levels of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [8]. In various medical diseases, such as pharyngitis, obstructive sleep apnea, malignancies, sepsis, infectious diseases, major cardiac events, and ischemic stroke NLR has been widely associated with disease progression and patient outcomes [9–18]. These relationships can demonstrate that mentioned illnesses might develop due to severe inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

As previously mentioned, the role of inflammation was proved in AR, so studying NLR in this disease makes sense. We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to assemble all information on the prognostic role of the NLR in AR and determine whether NLR is associate with disease severity and comorbidities. By doing this, we aim to improve clinicians’ understanding of AR and the role of inflammation in this disorder.

Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis was carried out based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline.

Literature Search Strategy

We carried out a systematic search using various combinations of the keywords “Allergic rhinitis,” “neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio,” and “NLR” in the SCOPUS, PUBMED, and WEB OF SCIENCE databases from the beginning to July 2023 to find studies that assessed the relationship between AR and NLR. Also, we carefully reviewed relevant articles’ reference lists for potentially related studies.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

PICOS (population, intervention, control, outcomes, and study design) principle was followed for study selection.

Primary Outcome

The PICO for the primary outcome, which was the differences between patients with moderate to severe AR and those with mild AR in NLR level, was as follows:

Population: Patients with moderate to severe AR

Intervention: Severe nasal polyps

Control: Patients with mild AR

Outcomes. NLR

Secondary Outcome

For the secondary outcome, which was the differences in NLR level between AR patients and healthy controls, the PICO was as follows:

Population: AR patients

Intervention: Diagnosed AR

Control: Healthy controls

Outcomes: NLR

In addition, we included studies reporting the relationship between NLR and AR commodities for qualitative review.

The articles’ language or publication date had no impression on reviewing them. Studies were excluded if 1) the data was insufficient; 2) they were duplicated articles; 3) participants were a known case of infections, severe systematic diseases, or autoimmune problems; and 4) letters, reviews, case reports, or conference reports.

Using the exclusion and inclusion criteria, two reviewers independently chose articles that fulfilled the requirements. The selected studies by the two reviewers were compared, and any disagreements between the lists were settled by discussion or via contact with the corresponding author.

Data Extraction

In the meta-analysis, the extracted data from the included articles were as follows: The study design, the sample size, the number of cases and controls, the age group (children or adults), the first author’s name, the nation, the publication year, the severity of AR, and the mean and standard deviation of the NLR.

Studies with a sample size of more than 200 were categorized as large. Two reviewers independently extracted the data using the abovementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were cleared up by discussion.

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently evaluated the included studies’ quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), which has a total score range of 0 to 9. (0–3: low quality, 4–6: moderate quality, and 7–9: high quality). The reviewers settled the differences by discussion.

Statistical Analysis

Standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to compare the differences in NLR levels between groups. The between-study heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s x2-based Q-statistic test and was quantified by the I2 value.

Heterogeneity was considered statistically significant if the I2 > 50% or P < 0.10. For the pooling analysis, there were two potential models; if significant heterogeneity was confirmed, the random-effect model was used. Otherwise, the other model, the fixed-effect model, was applied. Furthermore, subgroup analysis was carried out according to study design, sample size, NOS score, and age group. By using the Egger’s and Begg’s tests and visual checking of the funnel plot, publication bias was detected. If the P < 0.10, it was deemed statistically significant.

This meta-analysis was conducted with the help of the STATA software package (Version 10, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). All P values are two-tailed.

Results

Search Results and Included Studies

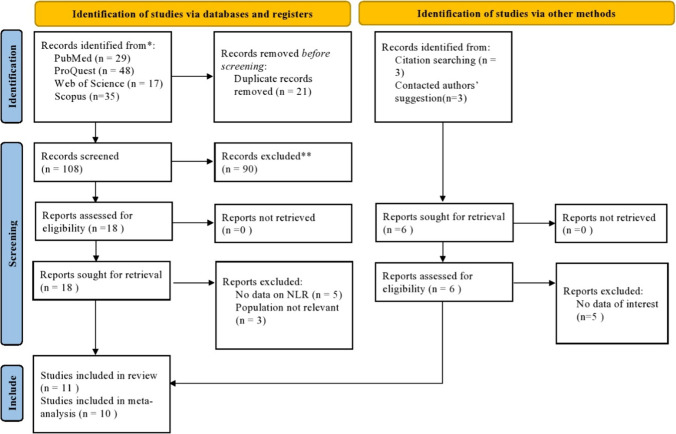

Our initial search yielded a total of 135 results. Figure 1 shows the multiple stages of study selection. Finally, eleven articles were included in the systematic review[19–29], among which ten were included in meta-analysis[19–26, 28, 29], including 1122 healthy controls and 1423 patients with AR. Table 1 shows the general features of the included articles in meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flow diagram for new systematic reviews, which includes searches of databases, registers, and other sources

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies in meta-analysis

| First author | Year | Country | Design | Sample size | Age group | Allergic rhinitis | Heathy controls | NOS score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mild | Moderate to severe | N | NLR | ||||||||||

| N | NLR | N | NLR | N | NLR | |||||||||

| Dogru | 2015 | Turkey | R | 618 | Children | 438 | 1.77 ± 1.67 | 132 | 1.58 ± 1.21 | 306 | 1.85 ± 1.82 | 180 | 1.70 ± 1.65 | 8 |

| Akgedik | 2017 | Turkey | R | 135 | Adults | 60 | 1.56 ± 0.67 | – | – | – | – | 75 | 1.72 ± 0.61 | 6 |

| Ekisi | 2019 | Turkey | R | 196 | Children | 136 | 1.65 ± 0.90 | 45 | 1.48 ± 0.73 | 91 | 1.90 ± 1.13 | 60 | 1.42 ± 0.93 | 6 |

| Goker | 2019 | Turkey | P | 452 | Adults | 209 | 2.02 ± 1.24 | 76 | 1.62 ± 0.59 | 133 | 2.25 ± 1.45 | 243 | 1.70 ± 0.65 | 7 |

| Ha | 2019 | Korea | P | 271 | Children | 99 | 1.18 ± 1.69 | – | – | – | – | 172 | 1.02 ± 0.50 | 8 |

| Yazici | 2019 | Turkey | R | 92 | Adults | 46 | 2.04 ± 0.70 | – | – | – | – | 46 | 1.93 ± 0.70 | 6 |

| Cansever | 2022 | Turkey | R | 360 | Children | 200 | 1.64 ± 1.29 | – | – | – | – | 160 | 1.18 ± 0.31 | 6 |

| Branika | 2020 | Poland | P | 44 | Adults | 44 | – | 24 | 1.91 ± 2.11 | 20 | 5.19 ± 9.72 | – | – | 7 |

| Rohila | 2023 | India | P | 140 | Adults | 70 | 1.92 ± 0.66 | 35 | 1.68 ± 0.33 | 35 | 2.15 ± 0.81 | 70 | 1.54 ± 0.48 | 7 |

| Selcuk | 2022 | Turkey | R | 237 | Adults | 121 | 2.17 ± 1.15 | – | – | – | – | 116 | 2.27 ± 0.98 | 8 |

N Number; NLR Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; NOS Newcastle–ottawa quality assessment scale; R Retrospective; P Prospective

Primary Outcome: Differences Between Patients with AR and Healthy Controls in NLR Level

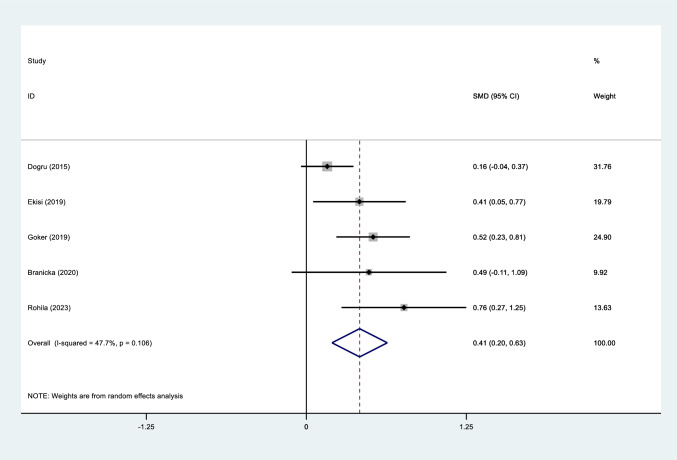

Patients with moderate to severe AR had significantly higher levels of NLR compared to those with mild AR (SMD = 0.41, 95%CI = 0.20–0.63, P < 0.001, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of differences in NLR level between patients with AR and healthy controls

classifying studies into two groups of studies on children and adults revealed that NLR was higher in moderate to severe AR than other group in both groups of studies (SMD = 0.24, 95%CI = 0.01- 0.47, P = 0.03, SMD = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.34- 0.80, P < 0.001, respectively, Figure S1).

Subgrouping according to study design showed higher levels of NLR among patients with more severe form than other group among either retrospective (SMD = 0.24, 95%CI = 0.01–0.47, P = 0.03) or prospective (SMD = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.34–0.80, P < 0.01) studies (Figure S2).

Classifying studies into two groups of high and moderate quality studies revealed that NLR was higher in moderate to severe AR than other group in both groups of studies (SMD = 0.43, 95%CI = 0.15–0.71, P < 0.01, SMD = 0.41, 95%CI = 0.05–0.77, P = 0.02, respectively, Figure S3).

When classifying studies according to sample size, we found higher level of NLR among patients with moderate to severe AR compared to other group in small studies (SMD = 0.53, 95%CI = 0.27–0.79, P = 0.03) but not in large studies (SMD = 0.33, 95%CI = − 0.02–0.68, P = 0.06, Figure S4).

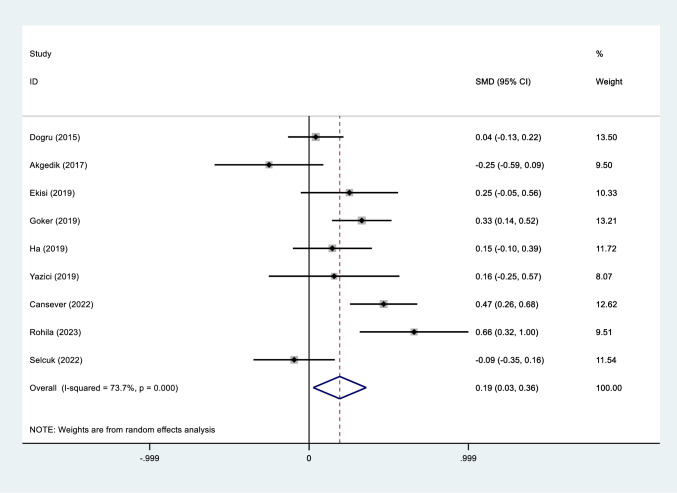

Secondary Outcome: Differences Between Patients with AR and Healthy Controls in NLR Level

Significantly higher values of NLR was observed in AR patients compared to healthy controls (SMD = 0.19, 95%CI = 0.03–0.36, P = 0.03, Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis based on age group yielded that that AR patients had a significantly higher level of NLR compared to healthy controls among children (SMD = 0.22, 95%CI = 0.02–0.43, P = 0.03) but not among adults (SMD = 0.16, 95%CI = − 0.13–0.46, P = 0.28, Figure S5).

Subgroup analysis based on design of studies showed that the NLR level of patients with AR was significantly higher compared to that of healthy controls in prospective studies (SMD = 0.35, 95%CI = 0.11–0.60, P = 0.03), but not in retrospective studies (SMD = 0.10, 95%CI = − 0.11–0.32, P = 0.5, Figure S6).

Subgroup analysis based on NOS scores of included studies demonstrated that the NLR level of patients with AR was similar to that of healthy controls in moderate (SMD = 0.17, 95%CI = − 0.14 –0.49, P = 0.27) or high-quality studies (SMD = 0.20, 95%CI = − 0.01–0.41, P = 0.06, Figure S7, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of differences in NLR level between patients with moderate to severe AR and those with mild AR

In the subgroup analysis according to sample size, we found that the NLR level of patients with AR was similar to that of healthy controls in either large (SMD = 0.18, 95%CI = − 0.01–0.38, P = 0.06) or small studies (SMD = 0.19, 95%CI = 0.03–0.38, P = 0.27, Figure S8).

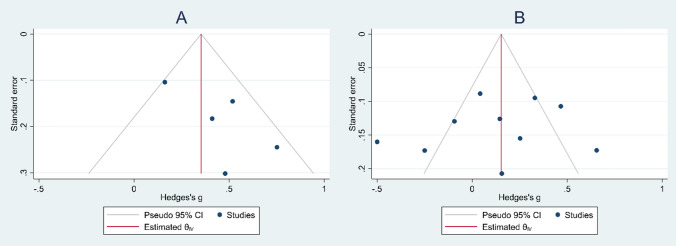

Publication Bias

Funnel plots showed no publication bias among studies on either primary (Egger’s test P = 0.06, Begg’s test P = 0.4) or secondary outcome (Egger’s test P = 0.6, Begg’s test P = 0.5, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot assessing publication bias; A) Primary outcome: differences in NLR level between patients with moderate to severe AR and those with mild AR; B) Secondary outcome: the differences in NLR level between patients with AR and healthy controls

Other Results

AR had two main subtypes: persistent and intermittent. Two studies compared NLR levels of patients with these two different types to evaluate if clinicians predict persistency of AR in patients [20, 27]. Kant et al. in 2021 conducted a retrospective study on 45 patients with intermittent AR and 160 patients with persistent AR and found that patients with intermittent type had significantly higher levels of NLR (2.17 ± 0.6) compared to other group (2.04 ± 0.8) (P = 0.04). NLR > 1.62 could predict persistent AR, with specificity of 88.1%, sensitivity of 42.8%, and AUC of 0.602 [27].

In contrast, Cansever et al. reported that patients with persistant type had higher level of NLR (n = 87, NLR = 2.49 ± 1.58) compared to other group (n = 113, NLR = 0.98 ± 0.26, P < 0.001) in a retrospective study in Turkey [20].

In addition, AR patients are at greater risk of rhino-sinusitis, asthma, and other related upper airway diseases. Interestingly, it was found that NLR could associate with some comorbidities of AR. For example, Akgedik et al. conducted a retrospective study, on 143 patients with AR, of which 83 had asthma as a major comorbidity of AR and compared them in NLR level. It was reported that AR patients with asthma had higher level of NLR (median = 1. 83, 95%CI = 1.43–2.45) compared to AR patients without asthma (median = 1.66, 95%CI = 1.07–1.96) [19].

In addition, Selçuk et al.,in 2023, in a retrospective study on 121 patients with AR and 101 patients with non-allergic rhinitis, found no difference between these two groups in NLR (2.17 ± 1.15 vs. 2.35 ± 1.01, respectively, P = 0.10) [29].

Discussion

The main finding of our meta-analysis was that patients with AR had a significantly higher level of NLR compared to healthy controls.

As AR is related to systemic inflammation in addition to nasal mucosa inflammation, it often co-occurs with other inflammatory diseases like sinusitis and asthma. In patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis who did not have asthma, nasal allergen provocation resulted in inflammatory alterations in the lower and upper airways, including increased bronchial hyperreactivity, increased adhesion molecule expression, and eosinophil infiltration [30, 31]. These findings show that an allergic nasal response causes inflammatory alterations throughout the body. Allergen exposure in sensitized individuals stimulates immune cells, such as dendritic cells, mast cells, mononuclear cells, TH lymphocytes, and others, both in lymphatic tissues related to the nose and within the nostrils [32]. Some of these TH cells move to the bone marrow, where they induce the production of inflammatory cells like mast cell precursors, eosinophils, and basophils [32–34].

There are several studies about the association between disease severity and NLR levels. According to a study, NLR levels were higher in patients with Behcet disease, a systemic inflammatory vascular illness, than healthy controls [35]. Similarly, it was observed that NLR levels rose with increasing Bell’s palsy grade according to another investigation. The disease is caused by facial nerve paralysis as a consequence of inflammation [36]. According to a study of individuals with IgA nephropathy, elevated NLR scores indicate more severe renal inflammation and a lower response to corticosteroid therapy [37]. These investigations came to two conclusions: first, inflammatory disorders cause greater NLR values than healthy people, and second, higher NLR values associated with the severity of the inflammatory condition. Higher NLR levels in severe inflammation imply neutrophil participation in the inflammatory process, the generation of inflammatory cytokines, and the modulation of numerous immunological responses by lymphocytes [37]. This condition confirms the relationship between illness severity and NLR, which is the most crucial finding of our research. In the literature, severity assessments include the acoustic rhinometry, VAS visual analog score, nasal cytology, and nitric oxide (NO) levels [38]. We recommend NLR as a marker of AR severity since they are simple, inexpensive, non-invasive, and widely accessible.

As mentioned earlier, inflammation affects AR, and a high NLR value may be a suitable biomarker for inflammation and AR. In order to recognize the relationship between NLR and AR, it is also essential to comprehend the function of neutrophils and lymphocytes in AR. NLR is calculated as a simple ratio of neutrophils, proinflammatory cells, lymphocytes, and regulatory immune cells. As a consequence, increased NLR implies increased inflammation, which contributes to the development of AR.

Prior study on neutrophil participation in AR has been considerable. When diseases like inflammation and infection occur, the bone marrow produces more neutrophils, and these cells go to the target tissues. These transient cells will leave the bone marrow in the absence of infection and perish within the boundaries of the bloodstream [39]. Since allergic rhinitis also relates to inflammation, blood neutrophils are expected to rise and move into the nose in AR patients. This observation is supported by the fact that neutrophils are among the most prevalent cells in studies examining nasal cytology in AR patients [40–42]. Since neutrophils enter the nose via the blood, an increase in NLR is predicted when blood neutrophils rise.

Lymphocytes are the other component of the NLR ratio. Th2 and Treg are primarily involved in allergic rhinitis, with Th17 having a noticeable impact in severely affected individuals and those with asthma [43]. Those with allergic rhinitis have an excess of Th2 cells in their nasal mucosa, which correlates with local eosinophils. In perennial rhinitis, IgE-producing plasma cells and memory Th2 cell population rise in afflicted areas [44]. CCR4 is the chemokine receptor that characterizes Th2 cells, and its ligands, macrophage-derived cytokine (MDC) and TARC, are elevated in APCs and nasal epithelial cells of allergic rhinitis. These numbers can be decreased by immunotherapy [44, 45]. Treg cells affect the inflammatory process in a variety of ways. Treg cells can suppress inflammation by secreting interleukins and can cause apoptosis in inflammatory T-cells like Th2 by expressing CD279 (aka programmed death 1) and CD152 (aka cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen) [45, 46]. The cytokine milieu, produced by monocytes and epithelial cells in the nose, can adversely affect the regulatory function of Tregs and other subsets of T cells related to allergic rhinitis [47].

Th17 is a type of T-cell associated with a fibrosis response in numerous autoimmune illnesses and asthma, and these cells are also linked to the neutrophilic inflammation of several asthma subtypes [47, 48]. Recent investigations found that elevated levels of Th17 can predict unsuccessful immunotherapy, and they discovered that patients suffering from severe allergic rhinitis had exhibited higher levels of Th17 [49–51].

Limitations and Strengths

This meta-analysis had a few limitations that should be mentioned. First, we discovered a high level of heterogeneity among the included studies. The random effect model was used to solve this matter; however, more than this model may be needed to completely eliminate heterogeneity. Second, the majority of the included articles were retrospective. The results of retrospective studies are not generally as strong as prospective studies. Third, most of the included articles were performed in Turkey. Further studies in other countries are needed to make a solid judgment on the role of NLR in AR. Even so, our study had three main strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study was the first meta-analysis that explored the relationship between NLR and AR. Second, we created clear criteria for inclusion and exclusion and screened the articles based on these criteria. Third, a reliable and thorough literature search was done in this study because the reference lists of the resulting articles were screened, and the search was not limited to language or date.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that NLR levels are increased in patients with AR than those without.

Our findings confirm the link between higher AR risk and elevated NLR levels. NLR is a distinct inflammatory marker whose increase in AR suggests an immune system imbalance in the disease’s etiology. Additionally, our results suggest that NLR is a potential biomarker that is simple to incorporate into clinical settings and can help predict and prevent AR. Finally, with the creation of novel indicators and therapeutic methods, we can more effectively manage and prevent AR to reduce long-term morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.K and M.S; Methodology: M.K; Formal analysis and investigation: M.K, S.K; Writing—original draft preparation: A.M, A.G; Writing—review and editing: A.G, A.B, S. FN; All authors read and approved the final manuscript and are responsible for data review.

Funding

There was no funding support.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis and does not require ethical approval.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Passali D, et al. The international study of the allergic rhinitis survey: outcomes from 4 geographical regions. Asia Pacific Allerg. 2018 doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2018.8.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wise SK, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: allergic rhinitis. Int Forum Allerg Rhinol. 2018;8(2):108–352. doi: 10.1002/alr.22073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arasi S, et al. The future outlook on allergen immunotherapy in children: 2018 and beyond. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0519-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dogru M, Citli R. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in children with atopic dermatitis: a case-control study. Clin Ter. 2017;168(4):e262–e265. doi: 10.7417/T.2017.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keskin H, et al. Elevated neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with euthyroid chronic autoimmune thyreotidis. Endocr Regul. 2016;50(3):148–153. doi: 10.1515/enr-2016-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayhan A, et al. Preoperative systemic inflammatory markers in different brain pathologies: an analysis of 140 patients. Turk Neurosurg. 2019;29(6):799–803. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.24244-18.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Özdemir HH, et al. Changes in serum albumin levels and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in patients with convulsive status epilepticus. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127(5):417–420. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2016.1187606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akıl E, et al. The increase of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naess A, et al. Role of neutrophil to lymphocyte and monocyte to lymphocyte ratios in the diagnosis of bacterial infection in patients with fever. Infection. 2017;45:299–307. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0972-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Z, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(3):641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong C-H, Wang Z-M, Chen S-Y. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict mortality and major adverse cardiac events in acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 2018;52:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song S-Y, et al. Clinical significance of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with ischemic stroke or hemorrhagic stroke: an updated meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1032. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin Y, et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Clinics. 2015;70:524–530. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2015(07)10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yukkaldıran A, Erdoğan O, Kaplama ME. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios in otitis media with effusion in children: diagnostic role and audiologic correlations. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(3):e13805. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gungorer V, et al. The effect of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and thrombocyte index on inflammation in patients with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis syndrome. Indian J Rheumatol. 2020;15(1):11. doi: 10.4103/injr.injr_120_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rha M-S, et al. Association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67708-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dogru M, Mutlu RY. The evaluation of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in children with asthma. Allergol Immunopathol. 2016;44(4):292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tahseen R, et al. A correlational study on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in bronchial asthma. Adv Human Biol. 2023;13(1):68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akgedik R, Yağız Y. Is decreased mean platelet volume in allergic airway diseases associated with extent of the inflammation area? Am J Med Sci. 2017;354(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cansever M, Sari N. The association of allergic rhinitis severity with neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in children. Northern Clin İstanbul. 2022;9(6):602–609. doi: 10.14744/nci.2022.96236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dogru M, Evcimik MF, Cirik AA. Is neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio associated with the severity of allergic rhinitis in children? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3175–3178. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3819-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Göker AE, et al. The association of allergic rhinitis severity with neutrophil–lymphocyte and platelet–lymphocyte ratio in adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:3383–3388. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ha EK, et al. Shared and unique individual risk factors and clinical biomarkers in children with allergic rhinitis and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clin Respir J. 2020;14(3):250–259. doi: 10.1111/crj.13124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yazici D. Assessment of inflammatory biomarkers, total IgE levels, SNOT-22 scores in allergic rhinitis patients. ENT Updates. 2019;9(2):128–132. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yücel Ekici N. Is there any correlation between allergy and hematological parameters in children with allergic rhinitis? Kocaeli Medical Journal. 2019;8(1):29–34. doi: 10.5505/ktd.2019.04909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branicka O, et al. Elevated serum level of CD48 in patients with intermittent allergic rhinitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021;182(1):39–48. doi: 10.1159/000510166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kant A, Terzioğlu K. Association of severity of allergic rhinitis with neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, eosinophil-to-neutrophil, and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios in adults. Allergol Immunopathol. 2021;49(5):94–99. doi: 10.15586/aei.v49i5.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohila V, et al. Association of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio with persistent allergic rhinitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s12070-023-03557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selçuk A, Keren M. The evaluation of eosinophil-to-lymphocyte, eosinophil-to-neutrophil, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios in adults with allergic/non-allergic rhinitis. Gulhane Med J. 2023 doi: 10.4274/gulhane.galenos.2023.94840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braunstahl G-J, et al. Nasal allergen provocation induces adhesion molecule expression and tissue eosinophilia in upper and lower airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(3):469–476. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.113046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corren J, Adinoff AD, Irvin CG. Changes in bronchial responsiveness following nasal provocation with allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89(2):611–618. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90329-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denburg JA, et al. Systemic aspects of allergic disease: bone marrow responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(5):S242–S246. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaspar Elsas MIC, et al. Rapid increase in bone-marrow eosinophil production and responses to eosinopoietic interleukins triggered by intranasal allergen challenge. American J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17(4):404–413. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.4.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inman MD, et al. Allergen-induced increase in airway responsiveness, airway eosinophilia, and bone-marrow eosinophil progenitors in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21(4):473–479. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.4.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozturk C, et al. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and carotid–intima media thickness in patients with Behcet disease without cardiovascular involvement. Angiology. 2015;66(3):291–296. doi: 10.1177/0003319714527638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiliçkaya MM, et al. The importance of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with idiopathic peripheral facial palsy. Int J Otolaryngol. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/981950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang H, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: an effective predictor of corticosteroid response in IgA nephropathy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;74:105678. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bousquet J, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008. Allergy. 2008;63:8–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amulic B, et al. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:459–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelardi M, et al. The clinical stage of allergic rhinitis is correlated to inflammation as detected by nasal cytology. Inflamm Allergy-Drug Targets Formerly Current Drug Targets-Inflamm Allergy Discont. 2011;10(6):472–476. doi: 10.2174/187152811798104917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gelardi M., et al., (2014) Seasonal changes in nasal cytology in mite-allergic patients. Journal of inflammation research, 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Pelikan Z. Cytological changes in nasal secretions accompanying delayed nasal response to allergen challenge. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27(5):345–353. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3933a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osguthorpe JD. Pathophysiology of and potential new therapies for allergic rhinitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(5):384–392. doi: 10.1002/alr.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pawankar R, et al. Overview on the pathomechanisms of allergic rhinitis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1(3):157–167. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.3.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banfield G, et al. CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) in human allergen-induced late nasal responses. Allergy. 2010;65(9):1126–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sin B, Togias A. Pathophysiology of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(1):106–114. doi: 10.1513/pats.201008-057RN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wisniewski JA, L Borish. (2011) Novel cytokines and cytokine-producing T cells in allergic disorders. In: Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. OceanSide Publications. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Barnes PJ. Pathophysiology of allergic inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2011;242(1):31–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Till S. Mechanisms of immunotherapy and surrogate markers. Allergy. 2011;66:25–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nieminen K, Valovirta E, Savolainen J. Clinical outcome and IL-17, IL-23, IL-27 and FOXP3 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of pollen-allergic children during sublingual immunotherapy. Ped All Immunol. 2010;21(1‐Part‐II):e174–e184. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciprandi G, et al. TGF-β and IL-17 serum levels and specific immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(10):1247–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.