Abstract

Lingual thyroid is a rare, abnormal ectopic thyroid tissue seen at the base of the tongue. It is a rare embryological anomaly caused by the failure of the descendence of the thyroid gland from the foramen caecum to its normal prelaryngeal area. The main aim of our study is to discuss recent advancements in the management of lingual thyroid using coblation technology. We are discussing the prospective study of 12 lingual thyroid cases that came to the government ENT hospital, Koti, in Hyderabad, from July 2016 to July 2023. All patients were assessed by a detailed history, blood investigations, fine needle aspiration cytology, radiological investigations, technetium-99 scintigraphy, and an endocrinologist opinion. In our study, all cases were hypothyroid and showed difficulty in swallowing and a few cases showed bleeding from the mouth, and difficulty in breathing, hence all 12 cases underwent coblation-assisted excision of swelling and with lifelong thyroxine supplementation. For all 12 cases, demographic, clinicopathological data and radiological data were recorded. Treatment depends on the age of the patient, the severity of symptoms, precipitating factors like puberty or pregnancy, or any other comorbidities with the disease. In our study, all cases were symptomatic and hypothyroid status, hence all 12 cases underwent coblation-assisted excision of swelling and lifelong thyroxine supplementation. All cases were followed up for 2 years with good recovery, minimal patient discomfort after surgery, and lifelong levothyroxine supplementation. Lingual thyroids have a female preponderance. In our study, all were female. Thyroid scintigraphy plays an important role in diagnosis, along with ultrasonography. In all symptomatic cases, surgery with Coblation-assisted excision of swelling is the treatment of choice, with good recovery, minimal patient discomfort after surgery and with lifelong levothyroxine supplementation.

Keywords: Lingual thyroid, Technetium-99 scintigraphy, Levothyroxine, Coblation

Introduction

The thyroid gland, one of the largest endocrine glands, is situated at the level of the cricoid cartilage [1]. It descends from the base of the tongue to the neck through the thyroglossal duct, which is a slender tube connecting the thyroid gland to the tongue. This duct typically undergoes involution around the 6th to 8th week of embryonic development. The opening of the thyroglossal duct is called the foramen caecum, which is present at the base of the tongue posterior to the circumvallate papillae. The thyroid gland descends to meet the lateral ultimobranchial bodies, and the fusion of these leads to the formation of a functional, mature thyroid gland by the 3rd foetal month [2].

Lingual thyroid is a rare embryological condition with ectopic thyroid tissue found at the base of the tongue, caused by the failure of the thyroid gland to descend to its normal cervical position. It generally originates from the epithelial tissue of the non-obliterated thyroglossal duct [3]. Nine per cent of ectopic thyroid tissue is found at the base of the tongue. The prevalence of lingual thyroid disease varies from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 300,000, and the incidence ranges from 1:4000 to 1:10,000 [4]. It is more frequently observed in females than in males, and in 70% of cases, normal thyroid tissue is absent, with a ratio of 7:1 [5]. Ectopic thyroid tissue can occur in any age group but is more commonly seen in childhood, adolescence and menopause.

Materials and Methods

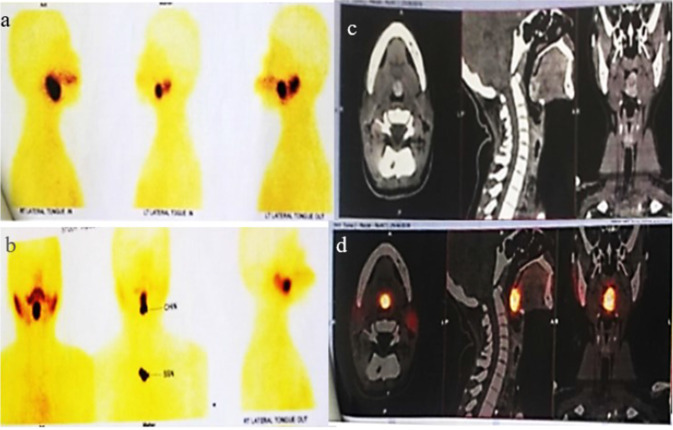

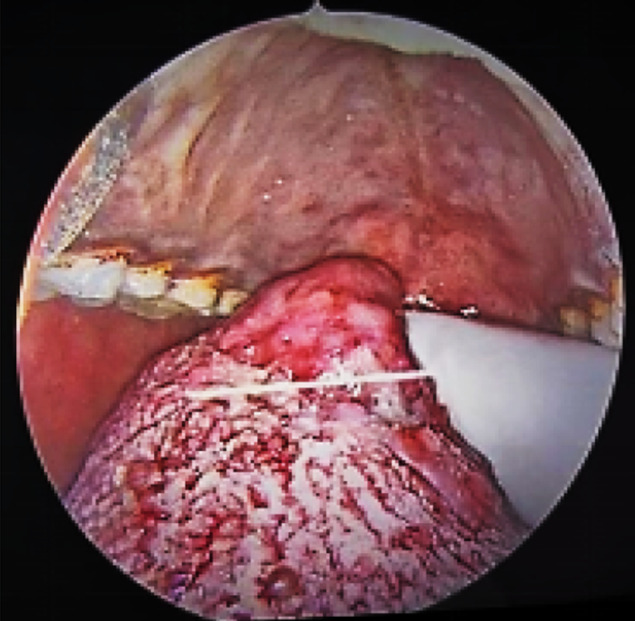

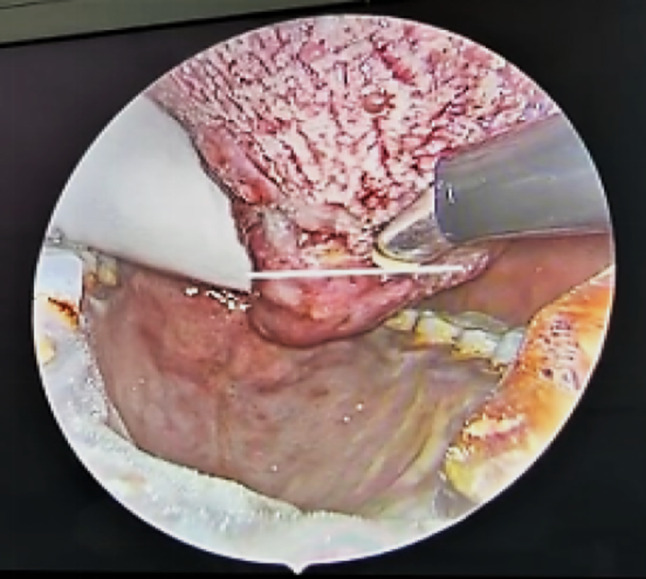

Our study included a prospective study of 12 cases of lingual thyroid cases that came to the government ENT hospital, in Hyderabad, India, from July 2016 to July 2023. All 12 cases were female, hypothyroid and symptomatic, a detailed history was taken, and they underwent all required blood investigations, videolaryngoscopy showed swelling at the base of the tongue (Fig. 1). Ultrasonography showed an absence of thyroid in the neck (Fig. 2). CT scanning and ultrasonography showed the size and exact location of the ectopic thyroid. Technetium-99 scintigraphy confirmed the only functioning thyroid in all the patients was at the base of the tongue, which is called the lingual thyroid (Fig. 3a, b, c, d). All patients were evaluated by an endocrinologist for hormonal status and were given the required dosage of hormone replacement therapy with levothyroxine. In our study all 12 cases were hypothyroid and showed difficulty in swallowing and few cases showed symptoms of bleeding from the mouth or tongue, or difficulty in breathing. Hence, under general anesthesia, all cases underwent coblation-assisted excision of the swelling trans-orally by the Evac70 hand piece, Arthrocare coblation wand (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

shows a lingual thyroid swelling on the tongue

Fig. 2.

Ultrasonography shows the absence of the thyroid gland in the neck

Fig. 3.

a–d shows thyroid scintigraphy fused with SPECT-CT (single photon emission computed tomography) image

Fig. 4.

shows coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid swelling using a coblation wand

Surgical Technique

The patient was placed in the rose position with an oro-endotracheal tube placed in situ under general anaesthesia. With the help of Boyle Davis, the swelling in the mouth was exposed; an alternative to the exposure of the swelling was by pulling off the tongue by silk suture. A throat pack was placed around the endotracheal tube to prevent aspiration of blood and secretions. Mass was grasped with Dennis Brown Tonsil Holding Forceps retracted posteriorly and dissected using the coblation technique with the Evac 70 wand, and retracted and dissected the swelling to its sides. Later, posteriorly, it is retracted and completely dissected the entire swelling from the normal tissue and sent for histopathological examination. Heomastasis was secured, and the procedure was uneventful in all the cases. The postoperative care was similar to the tonsillectomy procedure, and the postoperative condition of all the cases was uneventful, with very little pain and no postoperative hemorrhage or any other complication noted in any case of our study.

The Histopathological examination showed tissue lined by stratified squamous epithelium with subepethelium thyroid tissue presented in lobules and thyroid follicles lined with flattened cuboidal cells and lumen filled with colloid and blood vessels in the intervening stroma (Fig. 5a, b, c). These features confirmed swelling as lingual thyroid in all 12 cases, and patients were started on levothyroxine supplementation for life at a dose as advised by the endocrinologist. Patients after 5 days of the postoperative period were discharged and were regularly followed up every week until one month and later every 2 months for up to one year and every 4 months in the 2nd year of the postoperative period with the surgeon. They were also reviewed by an endocrinologist at regular intervals for their normal thyroid hormone levels.

Fig. 5.

shows the histopathological examination of the specimen at a 4× magnification b 10× magnification c 40× magnification using hematoxylin and eosin stain

Results

Lingual thyroid is often asymptomatic, but along with hypothyroidism, it may present with complaints of difficulty swallowing, bleeding, cough, change in voice, and difficulty breathing. Treatment depends on the age of the patient, the severity of symptoms, precipitating factors like puberty or pregnancy, or any other comorbidities with the disease.

In our study, all 12 cases were female and with hypothyroidism. For all 12 cases, demographic, clinicopathological data and radiological data were recorded. All 12 cases were symptomatic and showed difficulty in swallowing, 6 cases showed bleeding from the mouth or the tongue, 1 case complained of difficulty in breathing and 1 case with irregular menstruation, hence all 12 cases underwent coblation-assisted excision of swelling and with lifelong thyroxine supplementation. All cases were followed up for 2 years with no postoperative complications and with good recovery, minimal patient discomfort after surgery using coblation technology, and lifelong levothyroxine supplementation with dosage as advised by the endocrinologist (Table 1).

Table 1.

shows the demographics of all 12 cases of lingual thyroid

| Cases | Age/gender | Complaints | Operative procedure | Follow-up period | Post-treatment complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing, bleeding on and off from the tongue | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 2 | 20 years/female | Irregular menstruation, difficulty in swallowing | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 3 | 27 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing, bleeding on and off from the tongue | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 4 | 16 years/female | Swelling in the throat, difficulty in swallowing | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 5 | 15 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing and difficulty in breathing | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 6 | 21 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing, bleeding from the tongue | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 7 | 18 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 8 | 25 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing, bleeding on and off from the tongue | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 9 | 26 years/female | Swelling in the throat, difficulty in swallowing | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 10 | 32 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing, bleeding from the tongue | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 11 | 17 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

| 12 | 25 years/female | Difficulty in swallowing, bleeding from the tongue | Coblation-assisted excision of lingual thyroid | 2 years | No |

Discussion

Ectopic thyroid tissue is any functioning thyroid tissue found outside the normal thyroid location [6]. It can occur between the geniohyoid and mylohyoid muscles (sublingual thyroid), the lingual thyroid, above the hyoid bone (prelaryngeal thyroid), and rare sites like the mediastinum, pericardial sac, heart [7], breast, oesophagus, trachea [8], lungs, duodenum, mesentery, and small intestine. Ectopic thyroid is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in infants.

Hickmann first recorded the first case of lingual thyroid in 1869, and Montgomery termed the condition lingual thyroid, thyroid follicles should be demonstrated in a tissue sample from the lesion [9]. Lingual thyroid is caused by a failure in the descent of the thyroid gland from the foramen caecum to the neck through the thyroglossal duct. Mutations of TITF-1 (Nkx2-1), Foxe 1 (TITF-2), and PAX-8 genes result in abnormal migration of the thyroid [10].

Lingual thyroid may be asymptomatic, and some cases are detected incidentally. A few cases are symptomatic, with complaints of difficulty in swallowing [11], cough [12], bleeding [13], lump in the throat, difficulty in breathing, upper airway obstruction, and change in voice [1]. Symptoms depend on the size and location of the swelling. Lingual thyroid is found in 9 per cent of the general population [4], and 33% of it shows hypothyroid status. In benign or malignant cases, most commonly, papillary carcinoma is noted in the ectopic thyroid tissue [4]. Other types, like medullary and Hurthle cell carcinomas, are described in a few cases. Most commonly seen in females than in males with a ratio of 7:1, prevalence varies from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 300,000.

Diagnosis is by Technetium 99 Scintigraphy is the main confirmatory investigation for the lingual thyroid. Computed tomography and Ultrasound are used to determine the size and exact location of the swelling. Fine needle cytology also helps in the diagnosis of lingual thyroid [14]. Histopathological examination of the specimen confirms the diagnosis of lingual thyroid.

Definitive treatment of lingual thyroid disease includes conservative management with levothyroxine supplementation for life in asymptomatic euthyroid cases. In symptomatic cases, treatment includes medical thyroid hormone replacement [15], surgical excision [16], transposition [17], and radioactive iodine 131 therapy [18]. Failure of medical therapy, obstructive symptoms, bleeding, cystic degeneration, or malignancies requires surgical excision. Levothyroxine is supplemented after surgical excision as lingual thyroid is the only thyroid tissue found in 70% of these patients [19].

Approaches include transoral coblation-assisted excision [20] with the advantage of less bleeding, no external incision, less postoperative pain and less duration of hospital stay. The only disadvantage is difficult exposure, but in all our cases, no difficulty in exposure was noted. Other approaches include transoral excision by tongue splitting [21], peroral excision by mandibular midline osteotomy, suprahyoid pharyngotomy, and combined transoral and transcervical approaches [22], but all of these have external incisions and may need a tracheostomy and postoperative complications. Differential diagnosis of lingual thyroid includes vascular tumours, telangiectatic granulomas, teratomas, and benign and malignant tumours at the posterior part of the tongue [23].

Conclusion

The lingual thyroid may be the only thyroid-producing tissue in the body, as in all our cases. Malignant transformation is also seen in a few cases but is rare; hence, careful evaluation using diagnostic techniques and appropriate treatment modalities is given with lifelong thyroxine supplementation. Coblation-assisted resection of the lingual thyroid is simple, reliable, and should be considered an alternative for surgically managing lingual thyroid cases.

Funding

This research did not receive any financial support from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures carried out in the studies involving human participants adhered to ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the patient’s parents and their relatives involved in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stoppa-Vaucher S, Lapointe A, Turpin S, Rydlewski C, Vassart G, Deladoëy J. Ectopic thyroid gland causing dysphonia: imaging and molecular studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(10):4509–4510. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanin LR, Greenberg LM. Pediatric upper airway obstruction due to ectopic thyroid: classification and case reports. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(4):422–427. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198804000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batsakis JG, El-Naggar AK, Luna MA. Thyroid gland ectopias. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105(12):996–1000. doi: 10.1177/000348949610501212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauk JJ. Ectopic lingual thyroid. J Pathol. 1970;102(4):239–243. doi: 10.1002/path.1711020408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas PS, Baker AW. Lingual thyroid. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32(2):123–124. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramzisham ARM, Somasundaram S, Nasir ZM. Lingual thyroid–a lesson to learn. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(4):533–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollice L, Caruso G. Struma cordis. Ectopic thyroid goiter in the right ventricle. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(5):452–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferlito A, Giarelli L, Silvestri F. Intratracheal thyroid. J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102(1):95–96. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100104104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkart CM, Brinkman JA, Willging JP, Elluru RG. Lingual cyst lined by squamous epithelium. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(12):1649–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillam MP, Kopp P. Genetic regulation of thyroid development. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13(4):358–363. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayram F, Külahli I, Yüce I, Gökçe C, Cagli S, Deniz K. Functional lingual thyroid as unusual cause of progressive Dysphagia. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2004;14(4):321–324. doi: 10.1089/105072504323030997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oppenheimer R. Lingual thyroid associated with chronic cough. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(4):433–434. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.6786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu TT, Su CY, Hwang CF, Chien CY, Eng HL. Massive bleeding from an ectopic lingual thyroid follicular adenoma during pregnancy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23(3):185–188. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2002.123432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovagnorio F, Cordier A, Romeo R. Lingual thyroid: value of integrated imaging. Eur Radiol. 1996;6(1):105–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00619974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weider DJ, Parker W. Lingual thyroid: review, case reports, and therapeutic guidelines. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86(6 Pt 1):841–848. doi: 10.1177/000348947708600621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams JD, Sclafani AP, Slupchinskij O, Douge C. Evaluation and management of the lingual thyroid gland. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105(4):312–316. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojananin S, Ungkanont K. Transposition of the lingual thyroid: a new alternative technique. Head Neck. 1999;21(5):480–483. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199908)21:5<480::AID-HED15>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park HM, Gupta S, Skierczynski P. Radioiodine-131 therapy for lingual thyroid. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2003;13(6):607. doi: 10.1089/105072503322238881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alt B, Elsalini OA, Schrumpf P, Haufs N, Lawson ND, Schwabe GC, et al. Arteries define the position of the thyroid gland during its developmental relocalisation. Dev Camb Engl. 2006;133(19):3797–3804. doi: 10.1242/dev.02550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabiei S, Rahimi M, Ebrahimi A. Coblation assisted excision of lingual thyroid. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;62(2):108–110. doi: 10.1007/s12070-010-0029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atiyeh BS, Abdelnour A, Haddad FF, Ahmad H. Lingual thyroid: tongue-splitting incision for transoral excision. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109(6):520–524. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100130609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zitsman JL, Lala VR, Rao PM. Combined cervical and intraoral approach to lingual thyroid: a case report. Head Neck. 1998;20(1):79–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199801)20:1<79::AID-HED13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch CA, Picken C, Clement SC, Azumi N, Sarlis NJ. Ectopic lingual thyroid: an otolaryngologic emergency beyond childhood. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2000;10(6):511–514. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]