Abstract

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue, including endometrial glands and stroma, outside of the uterine cavity. It is a prevalent condition worldwide, affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-age women and up to 50% of infertile women. Endometriosis manifests in three ways: superficial peritoneal endometriosis, deep infiltrative endometriosis, and ovarian endometriomas, with the possibility of coexistence among them. The disease presents with a range of symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility. Additionally, patients may experience nongynecological symptoms such as dyschezia, dysuria, hematuria, flank pain, and fatigue, among others. The ovaries are the most affected site in endometriosis, typically with cysts measuring less than 6 cm in diameter. Therefore, even in the presence of a large ovarian cyst or in asymptomatic patients, the consideration of an endometrial cyst should not be overlooked.

Keywords: Giant endometrioma, Endometriosis, Magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Endometriosis is a prevalent chronic inflammatory gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue, including endometrial glands and stroma, outside the confines of the uterine cavity. It affects approximately 10% of reproductive-age women and up to 50% of infertile women [1]. In women with chronic pelvic pain, some sources cite up to 90% incidence of endometriosis [2]. However, there is often a delay in diagnosing endometriosis, highlighting the need for improved recognition and early intervention.

Endometriosis manifests with various symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, infertility, and additional non-gynecological symptoms such as dyschezia, dysuria, hematuria, flank pain, and fatigue [1]. While laparoscopy or surgery with histological verification remains the definitive diagnostic method, imaging plays a crucial role in aiding treatment decisions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is frequently utilized as a complementary imaging modality, particularly in complex cases, and is recommended as a secondary option following ultrasound (US) [3].

There are 3 recognized types of endometriosis: superficial peritoneal endometriosis (< 5 mm), deep infiltrative endometriosis, and ovarian endometriomas, which can coexist [2]. Ovarian involvement is the most common site, occurring in approximately 20%-40% of cases, with the majority of endometriomas measuring less than 6 cm in diameter. However, the presence of larger endometriomas exceeding 10 cm, often referred to as giant endometriomas, is rare and can present diagnostic challenges for clinicians [4].

Case report

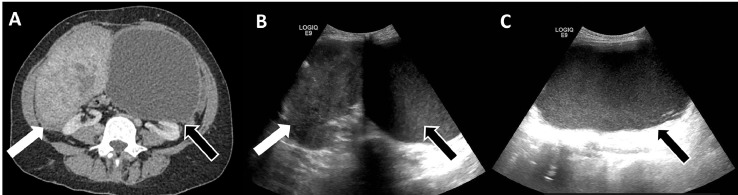

A 40-year-old female patient with Eisenmenger Syndrome, who was completely asymptomatic, visited a cardiologist for a routine appointment. During a physical examination, an abdominal mass was discovered. The patient denied experiencing weight loss or changes in urinary and bowel movements. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1A) was performed, revealing 2 masses in the abdominopelvic region. One mass appeared solid and originated from the right adnexal region, while the other had a cystic appearance and originated from the left adnexal region. The patient was referred to a gynecology service for further investigation, which included a pelvic ultrasound (US) examination and serum tumor marker tests.

Fig. 1.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography: demonstrated a solid right adnexal region mass (white arrow), and a cystic mass originated from the left adnexal region (black arrow). (B and C) Pelvic ultrasound: demonstrated a cystic mass (black arrows) in the left adnexal region. It was unilocular and homogenous, with low-level internal echoes, a well-defined wall, and no solid areas or internal blood flow. In the right adnexal region, a mass with a solid appearance and similar echogenicity to the myometrium (white arrow) was identified.

The US examination (Figs. 1B and C) showed a cystic mass (black arrow) in the left adnexal region. It was unilocular and homogenous, with low-level internal echoes, a well-defined wall, and no solid areas or internal blood flow. The estimated size was 14.0 × 19.3 × 10.6 cm. In the right adnexal region, a mass with a solid appearance and similar echogenicity to the myometrium (white arrow) was identified, measuring 8.4 × 6.0 × 8.5 cm. The right ovary was identified, but the left ovary was not visualized. Both masses observed in the US were suggestive of ovarian masses.

Due to the large size of the lesions, an MRI was performed. It revealed a right adnexal mass (Fig. 2A - white arrow) originating from the uterus, as indicated by the bridging vessel sign (Fig. 2A - red arrow). The characteristics of the mass were consistent with a leiomyoma. A cystic mass in the left adnexal region with 17.0 × 9.8 × 13.0 cm was also detected, with its origin identified as the left ovary, indicated by the claw sign (Figure 2B - green arrow). The signal on T1-weighted images (Figs. 2C and D – black arrows) showed homogeneous high-signal intensity, indicating an endometrioma. In the retrocervical region, an ill-defined infiltrative tissue was observed, hypointense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 2B - orange arrow), with some areas of high signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Fig. 2C - orange arrow). This finding was consistent with deep endometriosis, extending from the posterior uterine serosa to the retrocervical region and anterior wall of the rectosigmoid.

Fig. 2.

(A–D) Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a right adnexal mass with characteristics consistent with a leiomyoma (A - white arrow) originating from the uterus, as indicated by the bridging vessel sign (A - red arrow). Right ovary was also identified (blue arrow). A cystic mass (A – black arrow) with its origin identified as the left ovary, indicated by the claw sign (B - green arrow). In the retrocervical region, an ill-defined infiltrative tissue was observed, hypointense on T2-weighted images (B - orange arrow), with some areas of high signal intensity on T1-weighted images (C - orange arrow). This finding was consistent with deep endometriosis. The signal on T1-weighted images (C and D- black arrows) showed homogeneous high-signal intensity without solid components, indicating an endometrioma.

Serum tumor marker levels were the following: CA125 - 70.4 U/mL, CA19.9 - 383.1 U/mL, CA15.3 - 19.7 U/mL, βHCG - 0.29 IU/mL, AFP - 1.6 ng/mL, CEA - 3.5 ng/mL.

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, which revealed a large cystic mass in the left adnexal region adhered to the sigmoid colon. No ascites were found. Additionally, a well-defined solid nodule originating from the uterine fundus was detected. Left salpingo-ophorectomy and removal of the uterine nodule were performed. During the dissection, the cystic capsule ruptured, releasing fluid with a chocolate-like appearance. The histopathological examination confirmed that the cyst was an ovarian endometrioma, and the uterine nodule was a leiomyoma. The patient experienced a satisfactory post-operative recovery without any complications related to the surgery or her cardiovascular condition.

Discussion

Huge ovarian endometriomas are exceptionally rare. Only a few cases have been documented in the medical literature [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], and in all of those cases, the patients exhibited symptoms. Pre-operative diagnosis using MRI was possible in only 2 cases [6,11]. Table 1 summarizes those case reports. Our patient was completely asymptomatic, and there was no history of dyspareunia or infertility, as she was not sexually active.

Table 1.

Summary of giant ovarian endometriomas described in the literature.

| Author, year | Preoperative MRI | Age (years) | Symptoms | Size on largest axis (cm) | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yahya A, 2022 | Not available | 33 | aAbdominal pain; dysmenorrhea; heavy menstrual bleeding | 30.1 × 11.6 × 29.6 cm | Ovarian cystectomy |

| Yassae F, 2017 | Not available | 26 | Abdominal enlargement and distension | 25.0 × 20.0 × 10.0 cm | Ovarian cystectomy |

| Mishra TS, 2016 | Not available | 38 | Intermittent abdominal pain and distension; abdominal swelling and fever | 30.0 × 12.0 cm | Total abdominal hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Matsushima T, 2016 | T2-weighted image showed a cyst tumor with some low-intensity areas (clots) | 56 | Abdominal fullness | 44.0 cm | Bilateral adnexectomy and total hysterectomy |

| Yasar, L | Not available | 33 | Lumbar pain, nausea, and abdominal distension | 26.0 × 18.0 × 17.0 cm | Salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Hameed A, 2010 | Not available | 47 | Increase in abdominal circumference and fever | 33.0 × 23.0 cm | Subtotal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy |

| Andersen O, 2000 | Not available | 50 | Progressive malaise, nausea, anorexia, chils, and obstipation | > 20 cm (not exact size was informed) | Resection of bilateral ovarian endometriomas and bilateral salpingectomy |

| Ishikawa H, 1997 | Homogenous high-signal intensity on T1-weighted images and inhomogeneous low-signal intensity on T2-weighted images | 30 | Abdominal distension | 20.0 × 18.0 × 12.0 cm | Right adnexectomy and left ovarian cystectomy |

History of dyspareunia could not be ascertained because this patient was not sexually active.

Pelvic US is the initial imaging modality for identifying ovarian endometriomas, with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 90% [1]. Endometriomas can be solitary or multiple, unilateral, or, in nearly 50% of cases, bilateral. They typically appear as thick-walled cysts containing blood products from cyclic bleeding.

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that MRI has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 91% for diagnosing endometrial cysts [12]. On MRI, endometriomas typically exhibit bright signal intensity on T1-weighted images (T1 shortening, attributed to subacute hemorrhage and high protein content) and homogeneously low signal intensity on T2-weighted images (T2 shading, caused by iron and protein accumulation due to recurrent bleeding). T2 shading has a high sensitivity (93%) but poor specificity (45%) for diagnosing endometriomas. The presence of the T2 dark spot sign, characterized by small foci of very low signal intensity on T2-weighted images within the cyst but not in its wall, can be useful.

The differential diagnosis of ovarian endometriomas includes hemorrhagic cysts, teratomas, and ovarian carcinoma. Rupture and infection are among the most common atypical presentations of endometriomas [13]. Huge endometriomas are rare and may pose a diagnostic dilemma for clinicians. We must always consider the possibility of an endometrial cyst, even if a huge ovarian cyst is detected or if the patient is asymptomatic.

Author contributions

The authors were equally involved in this study.

Patient consent

A signed consent for the report publication was acquired from the patient.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Quesada J, Härmä K, Reid S, Rao T, Lo G, Yang N, et al. Endometriosis: a multimodal imaging review. Eur J Radiol. 2023;158 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha P, Sakala M, Chamie LP, Feldman M, Hindman N, Huang C, et al. Endometriosis MRI lexicon: consensus statement from the Society of abdominal radiology endometriosis disease-focused panel. Abdom Radiol. 2020;45(6):1552–1568. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foti PV, Farina R, Palmucci S, Vizzini IAA, Libertini N, Coronella M, et al. Endometriosis: clinical features, MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation. Insights Imag. 2018;9(2):149–172. doi: 10.1007/s13244-017-0591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercouris M, Klopper S, Swanepoel S, Laubscher M, Roche S, Kauta N. Giant ovarian endometrioma: a case report abstract. J West African Coll Surg. 2023;13:91–95. doi: 10.4103/jwas.jwas_223_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yassaee F, Abbasi H. Huge Endometrioma Mimicking Ovarian Cancer: A Case Report. Case Rep Clin Pract. 2017;2(4):91–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsushima T, Asakura H. Huge ovarian endometrioma that grew after menopause: case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(3):350–352. doi: 10.1111/jog.12885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra TS, Singh S, Jena SK, Mishra P, Mishra L. Giant endometrioma of the ovary: a case report. J Endometr. 2016;8(2):71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaşar L, Süha Sönmez A, Galip Zebitay A, Neslihan G, Yazıcıoğlu HF, Mehmetoğlu G. Huge ovarian endometrioma - a case report. Gynecol Surg. 2010;7(4):365–367. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hameed A, Mehta V, Sinha P. A rare case of de novo gigantic ovarian abscess within an endometrioma. Yale J Biol Med. 2010;83(2):73–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen O, Giustra P, Leidinger R. Giant endometrioma. Am J Surg. 2001;181(3):272–273. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishikawa H, Taga M, Haruki A, Shirasu K, Minaguchi H, Hara M. Huge ovarian endometrial cyst: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;74(2):215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PMM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009591.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brookmeyer C, Fishman EK, Sheth S. Emergent and unusual presentations of endometriosis: pearls and pitfalls. Emerg Radiol [Internet] 2023;30:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s10140-023-02128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]