Abstract

Existing approaches to 3D medical image segmentation can be generally categorized into convolution-based or transformer-based methods. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) demonstrate proficiency in extracting local features, they encounter challenges in capturing global representations. In contrast, the consecutive self-attention modules present in vision transformers excel at capturing long-range dependencies and achieving an expanded receptive field. In this paper, we propose a novel approach, termed SCANeXt, for 3D medical image segmentation. Our method combines the strengths of dual attention (Spatial and Channel Attention) and ConvNeXt to enhance representation learning for 3D medical images. In particular, we propose a novel self-attention mechanism crafted to encompass spatial and channel relationships throughout the entire feature dimension. To further extract multiscale features, we introduce a depth-wise convolution block inspired by ConvNeXt after the dual attention block. Extensive evaluations on three benchmark datasets, namely Synapse, BraTS, and ACDC, demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method in terms of accuracy. Our SCANeXt model achieves a state-of-the-art result with a Dice Similarity Score of 95.18% on the ACDC dataset, significantly outperforming current methods.

Keywords: 3D medical image segmentation, Dual attention, Depth-wise convolution, Swin transformer, InceptionNeXt

1. Introduction

In recent years, vision transformers (ViTs) [1] have gradually surpassed and replaced Convolution Neural Network (CNN) and found wide applications in various downstream tasks of medical imaging, including segmentation [2], [3], [4], [5], classification [6], [7], [8], [9], restoration [10], [11], [12], [13], synthesis [14], [15], [16], [17], registration [18], [19], [20], [21], and object detection in medical images [22], [23]. In particular, significant progress has been observed in 3D medical image segmentation with the adoption of Vision Transformers (ViTs) [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Transformers have emerged as powerful tools for medical image segmentation, either as standalone techniques or as components of hybrid architectures. The self-attention mechanism, a core component of transformers, plays a crucial role in their success by enabling direct capture of long-range dependencies. Drawing on the efficacy of self-attention, scholars have suggested incorporating spatial-wise attention alongside channel-wise attention within transformer blocks to capture interactions [29], [30], [31]. These dual attention schemes based on self-attention have demonstrated improved performance across medical image segmentation tasks [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. Taking inspiration from the aforementioned research, we propose a novel transformer block that leverages spatial-wise and channel-wise attention mechanisms to enhance the capture of both spatial and channel information in 3D medical images.

Drawing insights from the successful experiences of both ViT and CNN, ConNeXt [37] is proposed as a pure convolutional network that surpasses sophisticated transformer-based models in performance and it also has widespread applications in 3D medical image segmentation [37], [38], [39], [40]. However, ConNeXt faces challenges in terms of high computational FLOP demands associated with 3D depth-wise convolutions. Inspired by the recent InceptionNeXt [41], we further incorporate grouped depth-wise convolutions with different group convolution kernels in our novel architecture. Our approach allows extracting multiscale information while simultaneously reducing model computational complexity.

In this paper, we propose a synergistic hybrid DADC module combining spatial and channel-wise attention-based transformers with the multi-scale feature extraction capabilities of 3D depth-wise convolutions for processing 3D medical images. As a fundamental component, the DADC module is seamlessly incorporated into both the encoder and decoder sections within our SCANeXt network architecture. Our approach leverages the Swin Transformer-based [42] spatial-wise attention module to capture a broad range of spatial information, surpassing the capabilities of traditional ViTs-based spatial attention modules. Concurrently, the channel-wise attention transformer effectively captures channel information. To address the potential oversight of spatial details in the channel-wise transformer block, we introduce a gated-convolutional feed-forward network (GCFN) block. This block adeptly incorporates spatial information between layers within the channel-wise transformer, enhancing the overall depth of feature extraction. Our novel fusion mechanism seamlessly integrates these two distinct attention paradigms, forming a cohesive Dual Attention (DA) mechanism within the transformer framework in contrast to other methods that typically design spatial and channel attention separately. Complementing the DA transformer module, our Depthwise Convolution (DC) module divides the input into three distinct groups, each subjected to 3D grouped convolutions with kernel sizes of 3, 11, and 21, respectively. This stratification enables a comprehensive extraction of multi-scale features. Our evaluations of SCANeXt, conducted on three diverse public volumetric datasets, have consistently demonstrated its superiority in supervised segmentation tasks, significantly outperforming current state-of-the-art (SOTA) networks across all datasets.

We summarize our contributions as below:

-

•

We introduce a hybrid hierarchical architecture tailored for 3D medical image segmentation, aiming to leverage the strengths of both transformers' attention mechanism and depth-wise convolution. This amalgamation capitalizes on the unique advantages of each technique, resulting in enhanced segmentation performance.

-

•

We introduce a novel dual attention module that comprises a Swin Transformer-based spatial attention block and a channel attention block with the ability to capture local spatial information. This module effectively captures both short-range and long-range visual dependencies, enhancing the ability to understand complex image structures and relationships.

-

•

We redesign a depth-wise convolution module based on InceptionNeXt for 3D medical image segmentation to extract deeper-level information from feature maps processed by the dual attention module, resulting in significantly improved 3D medical image segmentation performance.

2. Related work

Depthwise Convolution Based Segmentation Methods: Deep learning techniques have gained widespread adoption in medical image segmentation tasks [43], [44], [45], [46], showcasing outstanding performance owing to their exceptional feature extraction capabilities. Numerous U-Net variants have been employed in medical image segmentation [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]. UNet++ and UNet3+ have improved upon the basic skip connection structure of UNet by integrating multi-scale skip connections and full-scale skip connections. This enhancement facilitates more effective feature extraction at various levels. Attention UNet [52] introduces attention gates to suppress irrelevant regions and focus on salient features. ResUNet [48] builds upon the UNet architecture by incorporating residual connections, while MultiResUNet [49] utilizes a multi-resolution approach to replace traditional convolutional layers. Among the notable UNet variants in recent years, nnUNet [53] stands out for its ability to autonomously adapt to data preprocessing and automatically select the optimal network architecture, eliminating the need for manual interventions. STNet [54] extends the nnUNet framework to construct a segmentation model with enhanced scalability and transferability.

Apart from these advancements in the traditional convolution-based UNet architecture, recent studies have started to reexamine the concept of depthwise convolution, tailoring its characteristics to enhance robust segmentation. Sharp U-Net [38] integrates innovative connections between the encoder and decoder subnetworks, which entail applying depthwise convolution to the encoder feature maps with a sharpening spatial filter. The 3D2U-Net [55] utilizes depthwise convolutions as domain adapters to extract domain-specific features within each channel.

Both studies show that utilizing depthwise convolution can improve volumetric problems. Only a tiny kernel size is utilized for depthwise convolution. Previous studies have explored the efficacy of large-kernel (LK) convolution in medical image segmentation. For instance, LKAU-Net [56] is the first use of LK and dilated depthwise convolution for brain tumor segmentation. Following this, ConvNeXt, a modified convolutional neural network model rooted in the standard ResNet, is introduced by Liu et al. [37]. It replaces the cutting-edge Swin transformer in multiple computer vision applications. Inspired by ConvNeXt, ASF-LKUNet [57] devises a residual block with enlarged kernels and incorporates large-kernel global response normalization (GRN) channel attention, leveraging depthwise convolution to concurrently capture both global and local features. Introducing volumetric depthwise convolution with substantial kernel dimensions (7×7×7), 3D-UXNet [58] emerges as the pioneer in simulating large receptive fields within the Swin transformer to generate self-attention. RepUX-Net [39] achieves better adaptation with extremely large kernel sizes (21×21×21) depthwise convolution to get a larger receptive field for volumetric segmentation. However, 3D-UXNet and RepUX-Net only use ConvNeXt blocks partially in a standard convolution encoder, limiting their possible benefits. Presented by Saika et al. [40], MedNeXt stands as the inaugural fully ConvNeXt 3D segmentation network. It facilitates scaling in width (more channels) and receptive field (larger kernels) at both standard and up/downsampling layers.

Transformer-based Segmentation Methods: To our best knowledge, TransUNet [2] is the first to use a hybrid CNN-Transformer encoder that combines spatial information at high resolution from CNN features with the global context extracted from Transformers in the U-shaped architecture, and the decoder maintains CNN-based upsampling structure. Meanwhile, SwinUNet [4] is the first pure Transformer-based U-shaped architecture. Self-attention mechanism in the transformer-based encoder captures local and global features after patch embedding. In the encoder, patch merging is applied for downsampling, while in the decoder, patch expanding is utilized to achieve upsampling.

SwinMM [59] employs a self-supervised learning approach, emphasizing the use of Swin Transformer for multiview information processing to enhance the performance of self-supervised learning in medical images. DS-TransUNet [60] adopts an effective dual-scale encoding mechanism that simulates non-local dependencies and multiscale contexts. It combines this mechanism with the Swin Transformer in both the encoder and decoder to enhance semantic segmentation quality. DS-TransUNet primarily focuses on improving segmentation performance through dual-scale encoding and a cross-fusion module. SwinPA-Net [61] introduces two modules, namely the Dense Multiplicative Connection (DMC) module and the Local Pyramid Attention (LPA) module, to aggregate multiscale contextual information in medical images. By combining these two modules with the Swin Transformer, it learns more powerful and robust features. ST-UNet [62] uses Swin Transformer as the encoder and CNNs as the decoder, introducing the Cross-Layer Feature Enhancement (CLFE) module in the skip connection part. This design aims to leverage low-level features comprehensively to enhance global features and reduce the semantic gap between the encoding and decoding stages. These Swin-based medical segmentation methods provide inspiration for subsequent Transformer-based medical image segmentation approaches. For instance, UNTER [25] and SwinUNETR [28] replace the hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture of the encoder in TransUNet with a cascade of several ViTs and Swin Transformer modules, respectively, and remain the decoder unchanged. DBT-UNETR [63] adopts the patch embedding and patch merging from SwinUNETR and replaces the encoder with a straightforward concatenation of the encoders from UNETR and SwinUNETR. nnFormer [26] builds upon the SwinUNet architecture by replacing the patch embedding and patch merging operations in the encoder with 3D convolutions, and the patch expanding operation in the decoder with 3D deconvolution. This enables the interleaving of convolutional and transformer-based blocks in the encoder and decoder, fully leveraging their respective advantages in feature extraction. TFCNs [64] introduce the Convolutional Linear Attention Block (CLAB), which encompasses two types of attention: spatial attention over the image's spatial extent and channel attention over CNN-style feature channels. The aforementioned methods simply rearrange the CNN and transformer modules within the encoder and decoder structures of UNet, without introducing any novel modules, resulting in limited improvements in segmentation performance. Compared with SwinUNet, MISSFormer [65] introduces a redesigned transformer block in the network structure of remix-FFN for integrating global information and local content. Additionally, MISSFormer proposes a novel ReMixed transformer context bridge to replace the skip connection between the encoder and decoder. CoTr, as introduced in [24], presents a novel mechanism for self-attention, termed the deformable self-attention. This mechanism constitutes the efficient DeTrans module, tailored for processing feature maps that are both multi-scale and high-resolution. These two approaches, which involve the redesign or improvement of the attention module in transformers, have also been widely applied in subsequent methods. Take the recent two SOTA methods as examples, VTUNet [27] proposes parallel cross-attention and self-attention in the decoder to preserve global context.

The central aspect of UNETR++ [66] involves introducing a novel efficient paired attention (EPA) block. This block effectively captures spatial and channel-wise discriminative features by employing inter-dependent branches that incorporate spatial and channel attention mechanisms. However, the channel attention and spatial attention modules in EPA are independently designed and share the parameters during attention computations, without taking into account the interplay between the two attention modules. While we design a channel attention module to acquire channel information, we also consider the impact on local spatial information and use the designed gate structure to better capture local spatial information and obtain better feature extraction results. Further, we use the Swin transformer in the spatial attention module to obtain spatial information at different scales.

3. Method

Introducing SCANeXt, a transformer backbone characterized by its cleanliness, efficiency, and effectiveness, integrating local fine-grained features with global representations. This section begins with an overview of the hierarchical layout of our model, succeeded by a comprehensive elucidation of both the dual attention module and the depthwise convolution module.

3.1. Overall architecture

Fig. 1 shows the SCANeXt architecture, which consists of a hierarchical encoder-decoder structure with skip connections between them, and convolutional blocks (ConvBlocks) for generating the prediction masks. The SCANeXt utilizes a hierarchical design that reduces feature resolution by a factor of two at each stage, efficiently capturing both local and global context information. Our SCANeXt framework distinguishes itself from the recently proposed TransUNet [60] and TFCNs [64]. TransUNet primarily focuses on integrating the U-Net architecture with Transformers to capture local features and global context information. In comparison, Our SCANeXt goes beyond by not only merging spatial and channel attention but also effectively extracting multi-scale features through depth convolution blocks. TFCNs introduce the Convolutional Linear Attention Block (CLAB) for spatial and channel attention while SCANeXt integrates transformer Attention Block with three components: Spatial Attention Block, Channel-wise Attention Block, and Spatial Channel Fusion Block. Inspired by the Swin Transformer, the Spatial Attention Block utilizes the W-MSA and SW-MSA structures to capture spatial features and the Channel-wise Attention Block comprises MDTA, GDFN, and GCFN, designed based on the MSA in Vision Transformer.

Figure 1.

Overview of our SCANeXt structure.

In our SCANeXt framework, the encoder is structured with four stages. Initially, during the first phase of patch embedding, the volumetric input undergoes a segmentation into 3D patches. This process is succeeded by the incorporation of our innovative dual attention and depthwise convolution (DADC) module. In the context of patch embedding, the division of each 3D input (volume) takes place, resulting in non-overlapping patches , where () signifies the resolution of each patch and represents the sequence length. The specified patch resolution is denoted as . Following this, the patches undergo projection into C channel dimensions, generating feature maps sized . In the subsequent encoder stages, downsampling layers employ non-overlapping convolution to decrease the resolution by a factor of two. Subsequently, the DADC block is integrated into the process.

In the proposed SCANeXt framework, each block of the DADC module integrates modules for spatial attention and channel attention, followed by a depthwise convolution module. The dual attention module effectively captures enriched representations by incorporating information from both spatial and channel dimensions. Simultaneously, the depthwise convolution module adjusts to a broad receptive field, enhancing features through the expansion of independent channels. To establish connectivity between encoder and decoder stages, skip connections are employed. These connections merge outputs at varying resolutions, facilitating the retrieval of spatial information that may be lost the downsampling procedures. This, in turn, contributes to the generation of more accurate predictions. In a parallel to the encoder's configuration, the decoder is structured into four stages. Within each stage, an upsampling layer is incorporated, employing deconvolution to double the resolution of feature maps. Following the upsampling layer, the DADC block is applied, with the exception of the last decoder stage. The channel count reduces by half between successive decoder stages. The final decoder's outputs are fused with convolutional feature maps to not only restore spatial information but also enhance feature representation. The resultant output undergoes further processing through 3×3×3 and 1×1×1 convolutional blocks, culminating in voxel-wise final mask predictions. Subsequently, we provide a detailed exposition on our DADC block.

3.2. Dual attention block

This section introduces the Dual Attention Block (DAB), designed to comprehensively capture spatial and channel-wise dependencies. Illustrated within the dashed box in Fig. 1, the DAB is composed of three fundamental sub-blocks: the Spatial Attention Block (SAB), Channel-wise Attention Block (CAB), and Spatial Channel Fusion Block (S-CFB). Incorporating the DAB into the standard transformer allows the synergistic utilization of spatial and channel-wise attention, enhancing the exploration of visual information for volumetric medical image segmentation.

3.2.1. Spatial attention block (SAB)

Illustrated in Fig. 2(a), our approach involves the utilization of window-based multi-head self-attention (W-MSA) and shift window-based multi-head self-attention (SW-MSA) [42] for applying spatial attention to volumetric medical image features. The rationale behind opting for W-MSA and SW-MSA to capture spatial dependencies lies in the distinct characteristics compared to the multi-head self-attention (MSA) in [67], the shifted window mechanism of W-MSA and SW-MSA can extract feature representations at several spatial resolutions while reducing computational complexity. Additionally, the W-MSA and SW-MSA blocks need to be modified to suit 3D medical image data. The two consecutive Swin transformer blocks depicted in Fig. 2(a) can be described mathematically as follows:

| (1) |

Equation (1) defines the operations of window-based MSA (W-MSA) and shifted window-based MSA (SW-MSA). Here, and represent the inputs to W-MSA and SW-MSA, while and denote their respective outputs. The final output of spatial attention feature is denoted as . To simplify the notation, we use U to represent the input feature map () and for the output feature map (). Additionally, MLP and LN stand for multi-layer perception and layer normalization, respectively.

Figure 2.

Components of the spatial-wise transformer.

In Fig. 2(b), the diagram illustrates the window-based multi-head self-attention. Specifically, the calculation of self-attention can be expressed as:

| (2) |

In Equation (2), represents the relative position of tokens within each window. Here, d denotes the dimension of the query and key, and corresponds to the number of patches in the 3D image window. The matrices for query , key , and value are computed as follows:

| (3) |

In Equation (3), represent the linear projection matrices, while denotes the input after the LN layer.

3.2.2. Channel-wise attention block (CAB)

The channel-wise transformer comprises three sequential components illustrated in Fig. 3: MDTA (multi-Dconv head transposed attention), GDFN (gated-Dconv feed-forward network), and GCFN (gated-Conv feed-forward network). In the work by Zamir et al. [68], the MDTA module within Restormer is designed to perform self-attention along the channel, diverging from the spatial dimension. This configuration allows for global attention computation with linear computational complexity. GDFN, on the other hand, selectively transmits valuable information to subsequent layers while suppressing less informative features. While Restormer has demonstrated competitive performance in natural image enhancement, our experiments revealed a limitation in terms of losing local spatial information. In addition to the parallel transfer of local spatial information through spatial attention blocks, we introduce a channel-wise attention block in our approach. This block incorporates a gated-conv feed-forward network (GCFN) to enhance the capture of local spatial information, thereby improving organ segmentation performance. The subsequent sections delve into the specifics of MDTA, GDFN, and GCFN.

Figure 3.

Components of the channel-wise transformer.

MDTAFig. 3(a) illustrates the MDTA module's structure. Starting with an input feature map , we first apply a layer normalization module to obtain . The matrices are then derived through a 1×1×1 pixel-wise convolution operation (for encoding channel-wise context) and a 3×3×3 channel-wise convolution operating (for aggregating pixel-wise cross-channel context). After reshaping operations, are obtained from , and , respectively. These matrices are utilized to generate a transposed-attention map , serving as an alternative to the extensive spatial attention map of size [67], [69]. The output feature of the MDTA module, denoted as , can be expressed as:

| (4) |

In Equation (4), the parameter α is a learnable scaling factor that governs the magnitude of the dot product output , and represents a linear projection matrix. It is crucial to highlight that the result of the self-attention operation undergoes reshaping to align with the input size of F.

GDFN Introducing a gating mechanism [67] proves beneficial in selectively transmitting valuable information to subsequent layers within the network architecture. This gating network effectively suppresses less informative features. In the GDFN module, as illustrated in Fig. 3(b) and utilized in [68], the gating mechanism is computed as follows:

| (5) |

In Equation (5), F and represent the input and output features, respectively. The operator ⊙ signifies element-wise multiplication, ϕ denotes the GELU non-linearity activation layer, and LN indicates layer normalization. The linear projection matrices are denoted as , , and . Additionally, and correspond to 3×3×3 channel-wise convolutions.

GCFN To address the potential loss of spatial information by the MDTA and GDFN modules, which predominantly leverage channel information for 3D medical image segmentation, a gated-conv feed-forward network (GCFN) module (depicted in Fig. 3(c)) is incorporated into the channel-wise transformer block. Notably, the GCFN differs from the GDFN in that the 3×3×3 channel-wise convolutions ( and ) in GDFN are replaced with 3×3×3 spatial-wise convolutions ( and ). Our hypothesis posits that spatial-wise convolutions may more effectively harness spatial information within volumetric medical images, thereby enhancing the segmentation of regions of interest.

3.2.3. Spatial-channel fusion block (S-CFB)

To maintain model conciseness, we opt for the element-wise sum to amalgamate the two attention feature maps:

| (6) |

In Equation (6), the symbols and stand for the spatial and channel-wise attention feature maps, respectively. The operation signifies the dropout, with a set probability of 0.1 for zeroing an element. Additionally, represents the layer normalization.

3.3. Depthwise convolution module

The 3DInceptionNeXt block is composed of 3×3×3 convolutional layers and multi-branch convolutional layers incorporating multi-scale depthwise separable kernels. In our experiments, we utilize kernel sizes of 3, 11, and 21 for these multi-scale depthwise separable kernels. Similar to ConvNeXt [37], the 3DInceptionNeXt block employs the inverted bottleneck design, where the channel size of the hidden 1×1×1 convolutional layer is four times wider than the input along the channel dimensions, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Components of the depthwise convolution module.

Depthwise separable kernel To address the computational and memory inefficiency associated with using a large kernel in the convolutional layer, we adopt the depthwise convolution layer with separable kernels, following the kernel design principles introduced in ConvNeXt and InceptionNeXt [41]. In this section, we decompose the kernel size of into and kernels. This decomposition is illustrated for 21×21×21, 11×11×11, and 3×3×3 kernels in Fig. 4. Beyond the computational and memory savings, it has been demonstrated that separable kernels enable the model to independently extract temporal and frequency features, leading to improved accuracy in medical image segmentation.

Inverted bottleneck In contrast to the convolutional design of the inverted bottleneck in MobileNetV2 [70], our approach involves situating the multi-branch convolutional layers at the top, preceding the application of 1×1×1 convolution layers to perform the channel-wise expansion and squeeze operation. This design choice, akin to the ConvNeXt block [37], aids in mitigating the memory footprint and computational time associated with the utilization of large kernels.

Non-linear layers To augment the nonlinearity within the model, batch normalization and RELU activation layers follow each separable kernel, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

3.4. Loss function

In alignment with the baseline approach UNETR++, we concurrently employ both the Dice Loss and the Cross-Entropy Loss to optimize our network. The expression for our loss function is as follows:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Equation (7) represents the total loss, while Equation (8) and Equation (9) correspond to the Dice Loss and Cross-Entropy (CE) Loss, respectively. These equations involve parameters where N represents the total number of voxels, C signifies the number of target classes, P denotes the Softmax output of the prediction segmentation, and Y represents the ground truth.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental setup

Our experimentation involves three benchmark datasets for medical image segmentation: Synapse [72], ACDC [73], and BraTS [74].

Datasets: Synapse is a multi-organ segmentation dataset, consisting of 30 abdominal CT scans in 8 abdominal organs (spleen, right kidney, left kidney, gallbladder, liver, stomach, aorta, and pancreas). We adhere to the dataset division strategy employed in TransUNet [2] and nnFormer [26]. Specifically, we use 18 cases to form the training set, of which 4 cases are chosen for the validation set, and the remaining 14 cases are used for testing.

ACDC comprises 100 scans from 100 patients, with target regions of interest (ROIs) including the left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), and myocardium (MYO). Following the data split protocol outlined in UNETR++ [66], we allocate 70 cases for training, 10 for validation, and 20 for testing purposes.

The Medical Segmentation Decathlon (MSD) BraTS dataset comprises 484 MRI scans with multi-modalities (FLAIR, T1w, T1-Gd, and T2w). The ground-truth segmentation labels cover peritumoral edema, GD-enhancing tumor, and the necrotic/non-enhancing tumor core. Evaluation of performance involves three combined regions: tumor core, whole tumor, and enhancing tumor. The dataset undergoes random partitioning into training (80%), validation (15%), and test (5%) sets.

Evaluation Metrics: Model performance evaluation relies on two metrics: the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and the 95% Hausdorff Distance (HD95). Typically, superior segmentation performance is reflected in a higher score for the region-based metric (DSC) and a lower score for the boundary-based metric (HD95). The calculation of similarity between the predicted segmentation P and the ground truth Y based on the region is given by Equation (10):

| (10) |

For boundary measurement, the calculation is articulated through Equations (11), (12), and (13):

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Equation (11) quantifies the unidirectional Hausdorff distance between Y and P, with representing the calculation of the 95th percentage of the distance between the boundary points of Y and P.

Implementation Details: Our approach is implemented in PyTorch v1.10.1, utilizing the MONAI libraries [75]. To ensure a fair comparison with both the baseline UNETR++ and nnFormer, we adopt identical input sizes, pre-processing strategies, and training data amounts. The models are trained on a single Quadro RTX 6000 24 GB GPU. For the Synapse dataset, all models undergo training for 1000 epochs with input 3D patches sized , employing a learning rate of 0.01 and weight decay of 3e−5. Concerning the ACDC and BRaTs datasets, we train all models at resolutions of and , respectively. During training, all other hyper-parameters are kept consistent with those of nnFormer. Specifically, the input volume is segmented into non-overlapping patches, which are then utilized for learning segmentation maps via back-propagation. Additionally, the same data augmentations are applied for UNETR++, nnFormer, and our SCANeXt throughout the training process.

4.2. Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

The evaluation of each task against state-of-the-art methods encompasses both quantitative and qualitative aspects.

4.2.1. Experimental results on the Synapse dataset

As listed in Table 1, results from another ten approaches are presented, including three classical methods namely, U-Net, TransUNet, Swin-UNet, and seven state-of-the-art methods namely UNETR, MISSFormer, nnUNet, SwinUNETR, nnFormer, 3D-UXNet, and UNETR++. We reproduce the results of nnUNet, SwinUNETR, 3D-UXNet, and UNETR++, while the results of the remaining methods are directly selected from their original papers, all the methods follow the same date split as mentioned in Section 4.1. According to Table 1, with the DSC of 89.67% and the HD95 of 7.47 mm, our method achieves the best performance in both evaluation metrics. Our method outperforms the second-best method UNETR++ by 2.45% in the DSC and by 0.06 mm in the HD95. Specifically, compared with nnFormer, 3D-UXNet, and UNETR++, SCANeXt achieves the highest DSC in the segmentation of the following three organs, which are gallbladder, liver, and aorta, and achieves the second highest DSC in the following three organs, which are spleen, right kidney, and pancreas.

Table 1.

The Synapse dataset's segmentation accuracy is assessed for various approaches, with evaluation metrics expressed in DSC (in %) and HD95 (in mm). Eight organs are subject to segmentation: spleen (Spl), right kidney (RKid), left kidney (LKid), gallbladder (Gal), liver (Liv), stomach (Sto), aorta (Aro), and pancreas (Pan). The optimal performance is highlighted in bold, while the second-best is underlined.

| Methods | Spl | RKid | LKid | Gal | Liv | Sto | Aor | Pan | Average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD95 ↓ | DSC ↑ | |||||||||

| U-Net [43] | 86.67 | 68.60 | 77.77 | 69.72 | 93.43 | 75.58 | 89.07 | 53.98 | - | 76.85 |

| TransUNet [2] | 85.08 | 77.02 | 81.87 | 63.16 | 94.08 | 75.62 | 87.23 | 55.86 | 31.69 | 77.49 |

| Swin-UNet [71] | 90.66 | 79.61 | 83.28 | 66.53 | 94.29 | 76.60 | 85.47 | 56.58 | 21.55 | 79.13 |

| UNETR [25] | 85.00 | 84.52 | 85.60 | 56.30 | 94.57 | 70.46 | 89.80 | 60.47 | 18.59 | 78.35 |

| MISSFormer [65] | 91.92 | 82.00 | 85.21 | 68.65 | 94.41 | 80.81 | 86.99 | 65.67 | 18.20 | 81.96 |

| nnUNet [53] | 94.81 | 84.41 | 87.30 | 66.22 | 96.15 | 75.20 | 91.73 | 76.04 | 12.56 | 83.98 |

| Swin-UNETR [28] | 95.37 | 86.26 | 86.99 | 66.54 | 95.72 | 77.01 | 91.12 | 68.80 | 10.55 | 83.48 |

| nnFormer [26] | 90.51 | 86.25 | 86.57 | 70.17 | 96.84 | 86.83 | 92.04 | 83.35 | 10.63 | 86.57 |

| 3D-UXNet [58] | 94.90 | 92.46 | 94.98 | 70.61 | 96.74 | 86.61 | 91.17 | 71.30 | 16.01 | 86.72 |

| UNETR++ [66] | 95.77 | 87.18 | 87.54 | 71.25 | 96.42 | 86.01 | 92.52 | 81.10 | 7.53 | 87.22 |

| Ours | 95.69 | 87.46 | 85.92 | 73.66 | 96.98 | 85.60 | 92.96 | 82.95 | 7.47 | 89.67 |

In Fig. 5, a qualitative comparison of SCANeXt with three state-of-the-art methods for abdominal multi-organ segmentation is presented. SCANeXt demonstrates a substantial reduction in the number of incorrectly segmented pixels overall. In the first row, both SwinUNETR and UNETR++ fail to achieve complete segmentation of the Sto region. Although 3D-UXNet performs slightly better, it still falls short compared to SCANeXt in terms of achieving complete segmentation. The most significant difference becomes evident in the fourth row, where 3D-UXNet and UNETR++ also struggle to achieve complete segmentation of the Pan region, while SwinUNETR succeeds in fully segmenting Pan, but makes errors at the boundaries of Sto and Liver regions. In the second row, SwinUNETR incorrectly segments a region that does not belong to any label as Pan. On the other hand, 3D-UXNet and UNETR++ both misclassify this region as Aor, with 3D-UXNet additionally incorrectly segmenting part of the Sto region. Only SCANeXt exhibits no misclassification in this scenario. Similar to the second row, in the third row, SwinUNETR, 3D-UXNet, and UNETR++ mistakenly segment regions without labels as liver or Rkid. Overall, SCANeXt achieves the closest segmentation results to the ground truth. This could be attributed to the SCANeXt method's incorporation of spatial and channel attention mechanisms in the transformer, combined with the advantages of separable kernel convolutions in extracting contextual features.

Figure 5.

Qualitative comparison of the segmentation performance for the Synapse dataset.

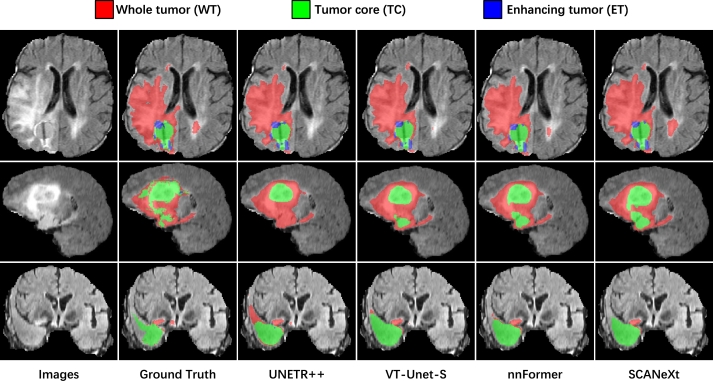

4.2.2. Experimental results on the BraTS dataset

The experiment results on the BraTS dataset are shown in Table 2. SCANeXt surpasses other methods in segmenting enhancing tumor (ET) regions, yielding the highest DSC and the lowest HD95. It also performs competitively in whole tumor (WT) segmentation, with only a marginal 0.3% DSC difference from the classical CNN-based method nnUNet, and achieves the lowest HD95 for WT segmentation among all compared methods. Furthermore, SCANeXt's average performance, in terms of DSC, is the highest, and its HD95 is the second-lowest. It is particularly noteworthy that SCANeXt's performance exceeds that of the dual-attention-based method UNETR++ by 1.80% in DSC, which validates the effectiveness of SCANeXt's redesigned dual-attention mechanism over the EPA block in UNETR++. Our SCANeXt outperforms the SOTA UNETR++ and the secondary nnFormer on average. All of them are based on the transformer structure. In nnFormer, they employed the basic transformer block as the main building block for local 3D volume embedding with high computational complexity, while our proposed DADC decomposes global transformer attention into spatial-wise and channel-wise transformer attention with high computation efficiency.

Table 2.

The BraTS dataset's segmentation accuracy is assessed for various approaches, with evaluation metrics expressed in DSC (in %) and HD95 (in mm). Segmentation is performed on three recombined regions: tumor core (TC), whole tumor (WT), and enhancing tumor (ET).

| Methods | WT |

ET |

TC |

Average |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD95 ↓ | DSC ↑ | HD95 ↓ | DSC ↑ | HD95 ↓ | DSC ↑ | HD95 ↓ | DSC ↑ | |

| nnUNet [53] | 3.64 | 91.9 | 4.06 | 81.0 | 4.95 | 85.6 | 4.60 | 86.2 |

| UNETR [25] | 8.27 | 78.9 | 9.35 | 58.5 | 8.85 | 76.1 | 8.82 | 71.1 |

| nnFormer [26] | 3.80 | 91.3 | 3.87 | 81.8 | 4.49 | 86.0 | 4.05 | 86.4 |

| VT-UNet-S [27] | 4.01 | 90.8 | 2.91 | 81.8 | 4.60 | 85.0 | 3.84 | 85.9 |

| UNETR++ [66] | 3.61 | 91.4 | 2.82 | 78.6 | 3.82 | 84.5 | 3.42 | 84.8 |

| Ours | 3.35 | 91.6 | 2.64 | 83.6 | 4.70 | 84.5 | 3.56 | 86.6 |

Qualitative segmentation results on the BraTS dataset are depicted in Fig. 6. Specifically, the first to third rows illustrate the segmentation outcomes of MRI scans in the transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes. In the transverse plane, UNETR++, VT-UNet-S, and nnFormer exhibit limitations in achieving complete segmentation of the WT subregion. In the coronal plane, these three methods struggle to accurately distinguish between the TC and WT regions. Additionally, in the sagittal plane, normal tissue is misidentified as tumor regions by all three methods. Nevertheless, SCANeXt consistently produces favorable segmentation results in all cases, showcasing its potential for effectively delineating irregular and complex lesions.

Figure 6.

Qualitative comparison of the segmentation performance for the BraTS dataset.

4.2.3. Experimental results on the ACDC dataset

The experiment results on the ACDC dataset are presented in Table 3. Compared with other methods, SCANeXt achieves the highest DSC for all three sub-structures segmentation, including RV, Myo and LV, surpassing the second-best methods by 5.04%, 2.95%, 1,01%. With an average DSC of 95.18%, SCANeXt significantly outperforms other methods, achieving a remarkable 3.57% higher accuracy compared to the second-best performing method, nnUNet.

Table 3.

The ACDC dataset's segmentation accuracy is assessed for various approaches. The evaluation metric utilized is DSC (in %). Segmentation is performed on three sub-structures, encompassing the right ventricle (RV), left ventricle (LV), and myocardium (MYO).

| Methods | RV | Myo | LV | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TransUNet [2] | 88.86 | 84.54 | 95.73 | 89.71 |

| Swin-UNet [71] | 88.55 | 85.62 | 95.83 | 90.00 |

| UNETR [25] | 88.49 | 82.04 | 91.62 | 87.38 |

| MISSFormer [65] | 86.36 | 85.75 | 91.59 | 87.90 |

| nnUNet [53] | 90.24 | 89.24 | 95.36 | 91.61 |

| 3D-UXNet [58] | 77.97 | 81.84 | 92.41 | 84.07 |

| nnFormer [26] | 91.18 | 86.24 | 94.07 | 90.50 |

| UNETR++ [66] | 91.47 | 86.47 | 94.25 | 90.73 |

| Ours | 96.51 | 92.19 | 96.84 | 95.18 |

Fig. 7 illustrates qualitative comparisons between SCANeXt and UNETR++ on the ACDC dataset, focusing on four different cases. In the first row, UNETR++ exhibits under-segmentation of the left ventricle (LV) cavity, whereas SCANeXt accurately delineates all three categories. The second row presents a challenging sample with comparatively smaller sizes for all three heart segments. In this instance, UNETR++ mistakenly segments a significant portion of the LV and myocardium (Myo) regions as the right ventricle (RV), while SCANeXt provides a more accurate segmentation. In the third row, UNETR++ incorrectly segments a large normal region as RV, which is similar to the problem shown by UNETR++ in the case of the third row in Fig. 5. In the last row, UNETR++ over-segments the RV cavity, while SCANeXt delivers improved delineation, producing a segmentation that closely aligns with the ground truth. These qualitative examples show that SCANeXt successfully achieves precise segmentation of the three heart segments without either under-segmenting or over-segmenting. This underscores the superior capability of SCANeXt, which leverages a collaborative approach combining the dual-attention module and depthwise separable convolution to learn highly discriminative feature representations.

Figure 7.

Qualitative comparison of the segmentation performance for the ACDC dataset.

4.2.4. Comparison of the number of network parameters

During our comparative experiments on the Synapse dataset, we recorded the model complexities of five methods, denoted as TransUNet, UNETR, Swin-UNETR, nnFormer, and UNETR++. We measured the model complexities using two metrics, parameters, and FLOPs (floating-point operations). Combining the complexity measurements with the corresponding Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) obtained for each method, we created an intuitive visualization in Fig. 8, where the circle sizes represent the computational complexity of each method.

Figure 8.

The model size vs. DSC is shown in this plot. Circle size indicates computational complexity by FLOPs.

From Fig. 8, it can be observed that methods such as TransUNet and UNETR, which combine convolutional and attention mechanisms in transformer operators, exhibit lower DSC values and higher parameter counts. SwinUNETR, which replaces ViT in UNETR with Swin Transformer, enhances DSC while reducing the model's parameter count. However, due to the inclusion of 3D moving window operations, SwinUNETR requires 4 times more FLOPs than UNETR. On the other hand, nnFormer, a pure transformer-based method, reduces FLOPs by 44.5% compared to SwinUNETR while improving accuracy. However, its UNet structure with encoder and decoder constructed entirely using transformers leads to a model with more than twice the parameters of SwinUNETR. UNETR++, an improvement on UNETR with revised attention modules from ViT, significantly enhances DSC while reducing model parameters and required FLOPs.

Our proposed SCANeXt, building upon UNETR++, shows a 0.98% increase in model parameters and a 5.31% increase in FLOPs but achieves a 2.81% improvement in DSC. This further demonstrates the superiority of our newly proposed attention mechanism over UNETR++'s EPA and showcases the better performance achieved with the incorporation of DCM. Overall, our findings underscore the effectiveness of the proposed attention mechanism and its combination with DCM in SCANeXt, offering notable improvements over UNETR++ and contributing to enhanced segmentation results.

4.3. Ablation studies

We conducted ablation experiments on the ACDC segmentation dataset to investigate the impact of the DAM and DCM modules on SCANeXt's performance, with the results shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Influence of DAM and DCM on the segmentation performance. w/o indicates that the module is not included.

When the DAM module was removed, leaving only the DCM module, SCANeXt transformed into a pure convolutional UNet segmentation network. On average, its performance improved by only 0.29% compared to the baseline 3D-UNXet based on depthwise convolution. The improvement was not significant, and in fact, its accuracy in segmenting Myocardium (Myo) was lower than 3D-UXNet. Both 3D-UNXet and SCANeXt with only DCM performed worse than the baseline UNETR. In contrast, retaining only the DAM module showed a performance improvement of 4.3% over UNETR and 0.95% over UNETR++, and outperformed both methods in segmenting all three subregions. When combining the DAM and DCM modules, SCANeXt's performance further improved by 3.5% compared to using only the DAM module. This suggests that the DCM module effectively extracted features from the feature maps obtained after applying the DAM module at multiple scales.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the DAM module plays a crucial role in enhancing segmentation performance, while the combination of DAM and DCM modules leads to the best overall performance improvement in SCANeXt.

4.4. Discussion

Through the comparative analysis of experimental results, SCANeXt demonstrates superior performance over state-of-the-art methods across datasets of varying difficulty, encompassing Synapse, BraTS, and ACDC. This compelling evidence underscores that the enhancement of the attention mechanism in the Transformer, coupled with its integration with depthwise convolution, represents a more advanced approach compared to existing methods. Ablation studies shed light on the pivotal role of two key modules, namely, DAM and DCM, indicating their potential to contribute to overall performance improvements. However, for a comprehensive model addressing medical image segmentation challenges, further validation across additional datasets is essential to ensure generalization, versatility, and robustness. Consequently, we anticipate that our research will attract future collaborations aimed at advancing algorithms for medical image segmentation.

5. Conclusion

This paper introduces SCANeXt as a versatile model designed for precise 3D medical image segmentation. We have re-designed a dual attention mechanism within the transformer framework. Notably, we introduced an innovative multi-Dconv head transposed attention to calculate attention along the channel dimension. In addition, we adapted the InceptionNeXt architecture to 3D medical images within the depthwise convolution module. Extensive experiments showcase SCANeXt's superiority over state-of-the-art approaches, particularly in terms of DSC and HD95 evaluation metrics. Through ablation experiments, we validated the proposed combination of Dual Attention-based Transformers and Depthwise Convolutions proves to be a superior approach in segmentation tasks. Our future research will predominantly concentrate on the development of more lightweight hybrid models based on ViT and CNNs. Additionally, we plan to explore segmentation methods that prioritize efficiency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yajun Liu: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Zenghui Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation. Jiang Yue: Supervision, Resources. Weiwei Guo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62271311, 62071333, and 62201343.

Contributor Information

Jiang Yue, Email: rjnfm3083@163.com.

Weiwei Guo, Email: weiweiguo@tongji.edu.cn.

Data availability

In our study, the datasets employed for experiments are readily accessible for download from public sources. Consequently, there was no need to create a dedicated database for storage. Readers can retrieve the pertinent datasets from the official website, adhering to the specified guidelines, to meet their specific requirements.

References

- 1.Dosovitskiy Alexey, Beyer Lucas, Kolesnikov Alexander, Weissenborn Dirk, Zhai Xiaohua, Unterthiner Thomas, Dehghani Mostafa, Minderer Matthias, Heigold Georg, Gelly Sylvain, et al. An image is worth words: transformers for image recognition at scale. 2020. arXiv:2010.11929 arXiv preprint.

- 2.Chen Jieneng, Lu Yongyi, Yu Qihang, Luo Xiangde, Adeli Ehsan, Wang Le Lu Yan, Yuille Alan L., Zhou Yuyin. Transunet: transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. 2021. arXiv:2102.04306 arXiv preprint.

- 3.Zhang Zhuangzhuang, Zhang Weixiong. Pyramid medical transformer for medical image segmentation. 2021. arXiv:2104.14702 arXiv preprint.

- 4.Cao Hu, Wang Yueyue, Chen Joy, Jiang Dongsheng, Zhang Xiaopeng, Tian Qi, Wang Manning. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022. Swin-Unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin Ailiang, Chen Bingzhi, Xu Jiayu, Zhang Zheng, Lu Guangming, Zhang David. DS- TransUNet: dual swin transformer U-Net for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022;71:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai Yin, Gao Yifan, Liu Fayu. Transmed: transformers advance multi-modal medical image classification. Diagnostics. 2021;11(8):1384. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11081384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsoukas Christos, Fredin Haslum Johan, Söderberg Magnus, Smith Kevin. Is it time to replace CNNs with transformers for medical images? 2021. arXiv:2108.09038 arXiv preprint.

- 8.Liu Chengeng, Yin Qingshan. Automatic diagnosis of Covid-19 using a tailored transformer-like network. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021;2010 IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Xiaohong, Qian Yu, Gao Alice. COVID-VIT: classification of Covid-19 from ct chest images based on vision transformer models. 2021. arXiv:2107.01682 arXiv preprint.

- 10.Zhang Zhicheng, Yu Lequan, Liang Xiaokun, Zhao Wei, Xing Lei. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part VI 24. Springer; 2021. Transct: dual-path transformer for low dose computed tomography; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korkmaz Yilmaz, Dar Salman U.H., Yurt Mahmut, Özbey Muzaffer, Cukur Tolga. Unsupervised MRI reconstruction via zero-shot learned adversarial transformers. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2022;41(7):1747–1763. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2022.3147426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo Yanmei, Wang Yan, Zu Chen, Zhan Bo, Wu Xi, Zhou Jiliu, Shen Dinggang, Zhou Luping. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part VI 24. Springer; 2021. 3D transformer-GAN for high-quality pet reconstruction; pp. 276–285. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Güngör Alper, Askin Baris, Soydan Damla Alptekin, Saritas Emine Ulku, Top Can Barış, Çukur Tolga. TranSMS: transformers for super-resolution calibration in magnetic particle imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2022;41(12):3562–3574. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2022.3189693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Xuzhe, He Xinzi, Guo Jia, Ettehadi Nabil, Aw Natalie, Semanek David, Posner Jonathan, Laine Andrew, Ptnet Yun Wang. A high-resolution infant MRI synthesizer based on transformer. 2021. arXiv:2105.13993 arXiv preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kamran Sharif Amit, Hossain Khondker Fariha, Tavakkoli Alireza, Zuckerbrod Stewart Lee, Baker Salah A. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 2021. Vtgan: semi-supervised retinal image synthesis and disease prediction using vision transformers; pp. 3235–3245. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ristea Nicolae-Catalin, Miron Andreea-Iuliana, Savencu Olivian, Georgescu Mariana-Iuliana, Verga Nicolae, Khan Fahad Shahbaz, Ionescu Radu Tudor. Cytran: cycle-consistent transformers for non-contrast to contrast ct translation. 2021. arXiv:2110.06400 arXiv preprint.

- 17.Dalmaz Onat, Yurt Mahmut, Çukur Tolga. Resvit: residual vision transformers for multimodal medical image synthesis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2022;41(10):2598–2614. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2022.3167808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Junyu, He Yufan, Frey Eric C., Li Ye, Du Yong. Vit-v-net: vision transformer for unsupervised volumetric medical image registration. 2021. arXiv:2104.06468 arXiv preprint.

- 19.Chen Junyu, Frey Eric C., He Yufan, Segars William P., Li Ye, Du Yong. Transmorph: transformer for unsupervised medical image registration. Med. Image Anal. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2022.102615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Yungeng, Pei Yuru, Zha Hongbin. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part IV 24. Springer; 2021. Learning dual transformer network for diffeomorphic registration; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Tulder Gijs, Tong Yao, Marchiori Elena. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part III 24. Springer; 2021. Multi-view analysis of unregistered medical images using cross-view transformers; pp. 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao Fangzhou, Liang Ming, Li Zhe, Hu Xiaolin, Song Sen. Evaluate the malignancy of pulmonary nodules using the 3-d deep leaky noisy-or network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019;30(11):3484–3495. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2019.2892409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Shijie, Zhou Hongyu, Shi Xiaozhou, Pan Junwen. Transformer for polyp detection. 2021. arXiv:2111.07918 arXiv preprint.

- 24.Xie Yutong, Zhang Jianpeng, Shen Chunhua, Xia Yong. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer; 2021. Cotr: efficiently bridging CNN and transformer for 3D medical image segmentation; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatamizadeh Ali, Tang Yucheng, Nath Vishwesh, Yang Dong, Myronenko Andriy, Landman Bennett, Roth Holger R., Xu Daguang. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. 2022. UNETR: transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Hong-Yu, Guo Jiansen, Zhang Yinghao, Yu Lequan, Wang Liansheng, Yu Yizhou. nnFormer: interleaved transformer for volumetric segmentation. 2021. arXiv:2109.03201 arXiv preprint.

- 27.Peiris Himashi, Hayat Munawar, Chen Zhaolin, Egan Gary, Harandi Mehrtash. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer; 2022. A robust volumetric transformer for accurate 3D tumor segmentation; pp. 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatamizadeh Ali, Nath Vishwesh, Tang Yucheng, Yang Dong, Roth Holger R., Xu Daguang. International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop. 2022. Swin UNETR: swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in MRI images. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burakhan Koyuncu A., Gao Han, Boev Atanas, Gaikov Georgii, Alshina Elena, Steinbach Eckehard. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022. Contextformer: a transformer with spatio-channel attention for context modeling in learned image compression; pp. 447–463. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding Mingyu, Xiao Bin, Codella Noel, Luo Ping, Wang Jingdong, Davit Lu Yuan. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022. Dual attention vision transformers; pp. 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gajbhiye Gaurav O., Nandedkar Abhijeet V. Generating the captions for remote sensing images: a spatial-channel attention based memory-guided transformer approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022;114 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Tongxue, Zhu Shan. Uncertainty quantification and attention-aware fusion guided multi-modal MR brain tumor segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hua Xin, Du Zhijiang, Yu Hongjian, Ma Jixin, Zheng Fanjun, Zhang Cheng, Lu Qiaohui, Zhao Hui. Wsc-trans: a 3D network model for automatic multi-structural segmentation of temporal bone ct. 2022. arXiv:2211.07143 arXiv preprint.

- 34.Huang Zhengyong, Zou Sijuan, Wang Guoshuai, Chen Zixiang, Shen Hao, Wang Haiyan, Zhang Na, Zhang Lu, Yang Fan, Wang Haining, et al. ISA-Net: improved spatial attention network for PET-CT tumor segmentation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;226 doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azad Reza, Arimond René, Khodapanah Aghdam Ehsan, Kazerouni Amirhosein, Merhof Dorit. Dae-former: dual attention-guided efficient transformer for medical image segmentation. 2022. arXiv:2212.13504 arXiv preprint.

- 36.Can Ates Gorkem, Mohan Prasoon, Celik Emrah. Dual cross-attention for medical image segmentation. 2023. arXiv:2303.17696 arXiv preprint.

- 37.Liu Zhuang, Mao Hanzi, Wu Chao-Yuan, Feichtenhofer Christoph, Darrell Trevor, Xie Saining. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022. A ConvNet for the 2020s; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zunair Hasib, Ben Hamza A. Sharp u-net: depthwise convolutional network for biomedical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;136 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee Ho Hin, Liu Quan, Bao Shunxing, Yang Qi, Yu Xin, Cai Leon Y., Li Thomas, Huo Yuankai, Koutsoukos Xenofon, Landman Bennett A. Scaling up 3D kernels with Bayesian frequency re-parameterization for medical image segmentation. 2023. arXiv:2303.05785 arXiv preprint.

- 40.Roy Saikat, Koehler Gregor, Ulrich Constantin, Baumgartner Michael, Petersen Jens, Isensee Fabian, Jaeger Paul F., Maier-Hein Klaus. Mednext: transformer-driven scaling of ConvNets for medical image segmentation. 2023. arXiv:2303.09975 arXiv preprint.

- 41.Yu Weihao, Zhou Pan, Yan Shuicheng, Wang Xinchao. Inceptionnext: when inception meets ConvNeXt. 2023. arXiv:2303.16900 arXiv preprint.

- 42.Liu Ze, Lin Yutong, Cao Yue, Hu Han, Wei Yixuan, Zhang Zheng, Lin Stephen, Guo Baining. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 2021. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ronneberger Olaf, Fischer Philipp, Brox Thomas. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18. Springer; 2015. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milletari Fausto, Navab Nassir, Ahmadi Seyed-Ahmad. 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV) Ieee; 2016. V-net: fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Badrinarayanan Vijay, Kendall Alex, Cipolla Roberto. Segnet: a deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017;39(12):2481–2495. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2644615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Çiçek Özgün, Abdulkadir Ahmed, Lienkamp Soeren S., Brox Thomas, Ronneberger Olaf. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2016: 19th International Conference, Athens, Greece, October 17-21, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 19. Springer; 2016. 3D U-Net: learning dense volumetric segmentation from sparse annotation; pp. 424–432. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Xiaomeng, Chen Hao, Qi Xiaojuan, Dou Qi, Fu Chi-Wing, Heng Pheng-Ann. H-DenseUNet: hybrid densely connected UNet for liver and tumor segmentation from CT volumes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2018;37(12):2663–2674. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2845918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diakogiannis Foivos I., Waldner François, Caccetta Peter, Wu Chen. Resunet-a: a deep learning framework for semantic segmentation of remotely sensed data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020;162:94–114. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ibtehaz Nabil, Sohel Rahman M. Multiresunet: rethinking the u-net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 2020;121:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Zongwei, Siddiquee Md Mahfuzur Rahman, Tajbakhsh Nima, Liang Jianming. Unet++: redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2019;39(6):1856–1867. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2959609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang Huimin, Lin Lanfen, Tong Ruofeng, Hu Hongjie, Zhang Qiaowei, Iwamoto Yutaro, Han Xianhua, Chen Yen-Wei, Wu Jian. 2020. Unet 3+: A Full-Scale Connected Unet for Medical Image Segmentation. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oktay Ozan, Schlemper Jo, Le Folgoc Loic, Lee Matthew, Heinrich Mattias, Misawa Kazunari, Mori Kensaku, McDonagh Steven, Hammerla Nils Y., Kainz Bernhard, et al. Attention U-Net: learning where to look for the pancreas. 2018. arXiv:1804.03999 arXiv preprint.

- 53.Isensee Fabian, Jaeger Paul F., Kohl Simon A.A., Petersen Jens, Maier-Hein Klaus H. nNU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods. 2021;18(2):203–211. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Ziyan, Wang Haoyu, Deng Zhongying, Ye Jin, Su Yanzhou, Sun Hui, He Junjun, Gu Yun, Gu Lixu, Zhang Shaoting, et al. Stu-net: scalable and transferable medical image segmentation models empowered by large-scale supervised pre-training. 2023. arXiv:2304.06716 arXiv preprint.

- 55.Huang Chao, Han Hu, Yao Qingsong, Zhu Shankuan, Zhou S. Kevin. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer; 2019. 3D U2-Net: a 3D universal U-Net for multi-domain medical image segmentation; pp. 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Hao, Nan Yang, Yang Guang. Annual Conference on Medical Image Understanding and Analysis. Springer; 2022. Lkau-net: 3D large-kernel attention-based u-net for automatic MRI brain tumor segmentation; pp. 313–327. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rongfang Wang, Zhaoshan Mu, Kai Wang, Hui Liu, Zhiguo Zhou, Shuiping Gou, Jing Wang, Licheng Jiao, ASF-LKUNet: adjacent-scale fusion U-Net with large-kernel for multi-organ segmentation, Available at SSRN 4592440. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Lee Ho Hin, Bao Shunxing, Huo Yuankai, Landman Bennett A. 3D UX-Net: a large kernel volumetric ConvNet modernizing hierarchical transformer for medical image segmentation. 2022. arXiv:2209.15076 arXiv preprint.

- 59.Wang Yiqing, Li Zihan, Mei Jieru, Wei Zihao, Liu Li, Wang Chen, Sang Shengtian, Yuille Alan L., Xie Cihang, Zhou Yuyin. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer; 2023. SwinMM: masked multi-view with swin transformers for 3D medical image segmentation; pp. 486–496. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin Ailiang, Chen Bingzhi, Xu Jiayu, Zhang Zheng, Lu Guangming, Zhang David. Ds-transunet: dual swin transformer u-net for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022;71:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Du Hao, Wang Jiazheng, Liu Min, Wang Yaonan, Meijering Erik. Swinpa-net: swin transformer-based multiscale feature pyramid aggregation network for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022 doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3204090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Jing, Qin Qiuge, Ye Qi, Ruan Tong. St-UNet: swin transformer boosted u-net with cross-layer feature enhancement for medical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023;153 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tao Haojie, Mao Keming, Zhao Yuhai. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) IEEE; 2022. DBT-UNETR: double branch transformer with cross fusion for 3D medical image segmentation; pp. 1213–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Zihan, Li Dihan, Xu Cangbai, Wang Weice, Hong Qingqi, Li Qingde, Tian Jie. International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks. Springer; 2022. Tfcns: a CNN-transformer hybrid network for medical image segmentation; pp. 781–792. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang Xiaohong, Deng Zhifang, Li Dandan, Yuan Xueguang. Missformer: an effective medical image segmentation transformer. 2021. arXiv:2109.07162 arXiv preprint. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Abdelrahman Shaker, Muhammad Maaz, Hanoona Rasheed, Salman Khan, Ming-Hsuan Yang, Shahbaz Khan Fahad. UNETR++: delving into efficient and accurate 3D medical image segmentation. 2022. arXiv:2212.04497 arXiv preprint.

- 67.Vaswani Ashish, Shazeer Noam, Parmar Niki, Uszkoreit Jakob, Jones Llion, Gomez Aidan N., Kaiser Łukasz, Polosukhin Illia. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017;30 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zamir Syed Waqas, Arora Aditya, Khan Salman, Hayat Munawar, Shahbaz Khan Fahad, Yang Ming-Hsuan. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022. Restormer: efficient transformer for high-resolution image restoration; pp. 5728–5739. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dosovitskiy Alexey, Beyer Lucas, Kolesnikov Alexander, Weissenborn D., Zhai X., Unterthiner T., Dehghani M., Minderer M., Heigold G., Gelly S., et al. An image is worth 16x16 words. 2020. arXiv:2010.11929 arXiv preprint.

- 70.Sandler Mark, Howard Andrew, Zhu Menglong, Zhmoginov Andrey, Chen Liang-Chieh. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2018. Mobilenetv2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao Hu, Wang Yueyue, Chen Joy, Jiang Dongsheng, Zhang Xiaopeng, Tian Qi, Wang Manning. European Conference on Computer Vision Workshops. 2022. Swin-UNet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Landman Bennett, Xu Zhoubing, Igelsias J., Styner Martin, Langerak T., Klein Arno. MICCAI Multi-Atlas Labeling Beyond Cranial Vault—Workshop Challenge. 2015. Miccai multi-atlas labeling beyond the cranial vault–workshop and challenge. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bernard Olivier, Lalande Alain, Zotti Clement, Cervenansky Frederick, Yang Xin, Heng Pheng-Ann, Cetin Irem, Lekadir Karim, Camara Oscar, Gonzalez Ballester Miguel Angel, Sanroma Gerard, Napel Sandy, Petersen Steffen, Tziritas Georgios, Grinias Elias, Khened Mahendra, Kollerathu Varghese Alex, Krishnamurthi Ganapathy, Rohé Marc-Michel, Pennec Xavier, Sermesant Maxime, Isensee Fabian, Jäger Paul, Maier-Hein Klaus H., Full Peter M., Wolf Ivo, Engelhardt Sandy, Baumgartner Christian F., Koch Lisa M., Wolterink Jelmer M., Išgum Ivana, Jang Yeonggul, Hong Yoonmi, Patravali Jay, Jain Shubham, Humbert Olivier, Jodoin Pierre-Marc. Deep learning techniques for automatic MRI cardiac multi-structures segmentation and diagnosis: is the problem solved? IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2018;37(11):2514–2525. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2837502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Menze Bjoern H., Jakab Andras, Bauer Stefan, Kalpathy-Cramer Jayashree, Farahani Keyvan, Kirby Justin, Burren Yuliya, Porz Nicole, Slotboom Johannes, Wiest Roland, Lanczi Levente, Gerstner Elizabeth, Weber Marc-André, Arbel Tal, Avants Brian B., Ayache Nicholas, Buendia Patricia, Louis Collins D., Cordier Nicolas, Corso Jason J., Criminisi Antonio, Das Tilak, Delingette Hervé, Demiralp Çağatay, Durst Christopher R., Dojat Michel, Doyle Senan, Festa Joana, Forbes Florence, Geremia Ezequiel, Glocker Ben, Golland Polina, Guo Xiaotao, Hamamci Andac, Iftekharuddin Khan M., Jena Raj, John Nigel M., Konukoglu Ender, Lashkari Danial, Mariz José António, Meier Raphael, Pereira Sérgio, Precup Doina, Price Stephen J., Riklin Raviv Tammy, Reza Syed M.S., Ryan Michael, Sarikaya Duygu, Schwartz Lawrence, Shin Hoo-Chang, Shotton Jamie, Silva Carlos A., Sousa Nuno, Subbanna Nagesh K., Szekely Gabor, Taylor Thomas J., Thomas Owen M., Tustison Nicholas J., Unal Gozde, Vasseur Flor, Wintermark Max, Ye Dong Hye, Zhao Liang, Zhao Binsheng, Zikic Darko, Prastawa Marcel, Reyes Mauricio, Van Leemput Koen. The multimodal brain tumor image segmentation benchmark (BRATS) IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2015;34(10):1993–2024. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2377694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Project-MONAI Medical open network for AI. 2020. https://github.com/Project-MONAI/MONAI

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

In our study, the datasets employed for experiments are readily accessible for download from public sources. Consequently, there was no need to create a dedicated database for storage. Readers can retrieve the pertinent datasets from the official website, adhering to the specified guidelines, to meet their specific requirements.