Abstract

Background

Diabetes self-management education and support is the cornerstone of diabetes care, yet <10% of adults with diabetes manage their condition successfully. Feasible interventions are needed urgently.

Objective

Our aim was to assess the feasibility of a cooking intervention with food provision and diabetes self-management education and support.

Design

This was a waitlist-controlled, randomized trial.

Participants/setting

Thirteen adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who participated in Cooking Matters for Diabetes (CMFD) participated in 2 focus groups.

Intervention

CMFD was adapted from Cooking Matters and the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes self-management education and support intervention into a 6-week program with weekly lesson–aligned food provisions.

Main outcome measures

Feasibility was evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively along the following 5 dimensions: demand, acceptability, implementation, practicality, and limited efficacy.

Statistical analysis

Two coders extracted focus group themes with 100% agreement after iterative analysis, resulting in consensus. Administrative data were analyzed via descriptive statistics.

Results

Mean (SD) age of focus group participants was 57 (14) years; 85% identified as female; 39% identified as White; 46% identified as Black; and income ranged from <$5,000 per year (15%) to $100,000 or more per year (15%). Mean (SD) baseline hemoglobin A1c was 8.6% (1.2%). Mean attendance in CMFD was 5 of 6 classes (83%) among all participants. Demand was high based on attendance and reported intervention utilization and was highest among food insecure participants, who were more likely to report using the food provisions and recipes. Acceptability was also high; focus groups revealed the quality of instructors and interaction with peers as key intervention strengths. Participant ideas for implementation refinement included simplifying recipes, lengthening class sessions, and offering more food provision choices. Perceived effects of the intervention included lower hemoglobin A1c and body weight and improvements to health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

The CMFD intervention was feasible according to the measured principles of demand, acceptability, implementation, practicality, and limited efficacy.

Keywords: Cooking, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Diabetes self-management education and support, Food insecurity, Social determinants of health

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic diseases in the United States.1,2 Adoption of evidence-based nutrition and physical activity habits is essential to its successful management.3 Standard of care includes diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) and medical nutrition therapy (MNT). DSMES teaches comprehensive lifestyle habits.4,5 MNT is nutrition education, counseling, and monitoring from a registered dietitian nutritionist.6–9 Both DSMES and MNT lower hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).4,5,9

Successful management of diabetes involves the maintenance of healthy HbA1c, body weight, blood pressure, blood lipids, and nonsmoking status. Less than 10% of people with diabetes meet these targets.10 People with food insecurity and diabetes, compared to those with diabetes alone, are less likely to meet these targets,11,12 possibly due to limited access to nutritious food.13

DSMES participants at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center expressed interest in learning practical cooking techniques. Teaching cooking and food skills reduces the burden of food insecurity,14 due to the ability of people with such skills to eat more nutritious meals for less money than people with poor cooking abilities.15 Although some studies have integrated cooking instruction with diabetes management,16–19 none have evaluated the feasibility of a randomized, controlled intervention focused on teaching food and cooking skills, offering lesson-aligned food provisions for at-home food preparation, and providing complementary DSMES. This feasibility study of Cooking Matters for Diabetes (CMFD)—completed in tandem with a randomized, wait-list controlled trial—fills this gap.20

METHODS

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a community outpatient care location in Columbus, OH, using flier advertisements; identification through standard-of-care DSMES exit survey responses indicating interest in learning about food and cooking; and electronic medical record review. Eligibility criteria included adults 18 years and older with HbA1c ≥7%, prior DSMES, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, and interest in cooking. Exclusion criteria included inability to participate in group education, any previous participation in Cooking Matters (CM), and inability to speak or understand English. In the waitlist-controlled design, participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to 2 intervention and 2 wait-list control arms after accounting for sex, as described in detail previously.20 Participants were compensated with $10 to $15 grocery store gift cards for completing assessments. Control participants received a maximum of $55, and intervention participants received a maximum of $45. All participants were recruited between June and September 2019. Participants were recontacted to participate in focus groups after completion of the trial. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH (Institutional Review Board number 2019H0095). The objectives, requirements, and risks and benefits of the study were clearly outlined and informed written consent was obtained for each participant. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04152811).

Intervention

CMFD was modified from Share Our Strength’s CM and DSMES. Sponsored by Walmart, CM provides families with knowledge and skills to prepare healthy, affordable meals. CM, implemented in central Ohio by Local Matters, includes hands-on, 6-week courses, which educate families on how to shop for healthy foods while saving money. CM also provides educational tools, such as recipes, to assist families in stretching their food budgets.

CMFD consisted of 2-hour weekly classes at a health center in Columbus, OH for 6 weeks. The classes were designed for up to 20 participants divided into smaller groups of 4 or fewer to enhance engagement. Each class included a DSMES portion (approximately 1 hour) and a hands-on cooking portion (approximately 1 hour), except for class number 5, which was an interactive grocery store tour. The DSMES portion covered all 9 indicators required by the American Diabetes Association.21,22 A CM instructor taught the cooking portion of the class, and the DSMES portion was taught by a registered dietitian nutritionist, who was also a certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES). A medical dietetics graduate student intern provided support for the intervention. Because the intervention followed DSMES guidelines, 1 hour of each of the 5 classes taught by the CDCES was billed to participants’ insurance.

The cooking portion covered food safety, knife skills, and techniques, Nutrition Facts and ingredients label reading, meal planning, budgeting, and shopping. Each class, with the exception of the grocery store tour, involved participants cooking a meal in groups. All participants then shared the meal together, with the goal of building a sense of community. The full curriculum can be found in Figure 1 (available at www.jandonline.org). At the end of class, participants received all ingredients needed to prepare 4 portions of that week’s recipes at home. At the end of the 6 weeks, participants received a cookbook with recipes from Share Our Strength’s CM program and a diabetes-related supplement.

Figure 1.

Cooking Matters for Diabetes course curriculum.

Feasibility Dimensions and Measures

The primary outcome was feasibility, assessed through the constructs of demand, acceptability, implementation, practicality, and limited efficacy (Figure 2; available at www.jandonline.org ).23 Demand for the intervention was determined by recruitment success, participant attendance, completion of surveys and HbA1c measurements, and self-reported intention to use intervention materials and lessons learned. Participant attendance was recorded by the study team. Completion of surveys and HbA1c was tracked in Research Electronic Data Capture.24,25 Acceptability was evaluated using focus group analysis. Implementation was assessed on the basis of the fidelity of DSMES and CM curricula achieved and on focus group–based intervention feedback from participants. Protocol fidelity was defined as 100% of DSMES and CM curricula items being covered in the classes and was monitored by the CDCES. Practicality was monitored through intervention cost and reimbursement received from payers. Themes regarding the intervention’s limited efficacy were developed on the basis of focus group discussion.

Figure 2.

Bowen’s dimensions of feasibility for the Cooking Matters for Diabetes (CMFD) evaluation.

Data Collection

The exit survey was collected immediately post intervention and managed online using Research Electronic Data Capture, hosted at The Ohio State University.24,25 The 2 questions analyzed from the exit survey were, “Did you prepare any of the recipes from class at home?” and “Do you plan to share things you learned in this course with your family or friends?”

Food security status was assessed with the 10-item US Adult Food Security Survey Module in a 3-stage design with screeners modified to a 30-day reference period.26 Participants who reported food insecurity at any time during the intervention (pre- or post-intervention assessments) or follow-up period (3-, 6-, or 12-month assessments) were considered food insecure in this analysis.

Qualitative data were collected via 90-minute, virtual focus groups after the end of the 12-month follow-up period. Focus groups were led by a qualitative expert (T.S.N.) with 2 note takers (A.W. and J.S.). All CMFD participants who attended at least 1 class were invited to participate in 1 of 2 focus groups. Thirteen volunteered. Five participated in the first focus group and 8 participated in the second. Participants received a $25 gift card. A semi-structured interview guide was used in the focus groups (Figure 3; available at www.jandonline.org ). The focus groups’ audio and video were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 3.

Focus group questions for Cooking Matters for Diabetes (CMFD) participants.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report baseline characteristics of the participants P values were generated with 2-sample t tests or χ2 tests, when appropriate. All quantitative analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 4.0.5.27

Qualitative Focus Group Data Analysis

Qualitative analyses were performed by 2 coders (A.W. and T.S.N.), who individually analyzed transcripts following Braun and Clarke’s28 thematic analysis methods and according to Bowen and colleagues’23 concept of feasibility. The coders met to iteratively refine themes with 100% agreement after consensus building. For anonymity, participants are referred to by pseudonyms in this article.

RESULTS

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

The baseline demographic characteristics of CMFD intervention and focus group participants are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic variables between focus group participants and nonparticipants. Mean (SD) age was 56.6 (13.6) years among focus group participants. Most (85%) were women and 46% identified as Black.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Cooking Matters for Diabetes participants according to whether they participated in the focus groups

| Characteristic | All participants (n = 48) | No focus group (n = 35) | Focus group participants (n = 13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

mean (SD)

|

||||

| Age, y | 56.5 (12.0) | 56.4 (11.6) | 56.6 (13.6) | .959 |

|

n (%)

|

||||

| Missing | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Sex | .153 | |||

| Female | 31 (65) | 20 (57) | 11 (85) | |

| Male | 17 (35) | 15 (43) | 2 (15) | |

| Race | .206 | |||

| African American | 19 (40) | 13 (37) | 6 (46) | |

| More than 1 race | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (15) | |

| White | 25 (52) | 20 (57) | 5 (39) | |

| Missing | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Ethnicity | 1.000 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 40 (83) | 28 (80) | 12 (92) | |

| Undisclosed | 3 (6) | 2 (6) | 1 (8) | |

| Missing | 5 (10) | 5 (14) | 0 (0) | |

| Marital status | .534 | |||

| Divorced | 8(17) | 4 (11) | 4 (31) | |

| Living with a partner | 3 (6) | 2 (6) | 1 (8) | |

| Married | 21 (44) | 16 (46) | 5 (39) | |

| Never married | 13 (27) | 11 (31) | 2 (15) | |

| Separated | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Widowed | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | |

|

mean (SD)

|

||||

| No. of Children | 0.512 (1.03) | 0.516 (1.00) | 0.500 (1.17) | .964 |

|

n (%)

|

||||

| Missing | 5 (10) | 4 (11) | 1 (8) | |

| Income | .480 | |||

| <$25,000 | 16 (33) | 13 (37) | 3 (23) | |

| $25,000-$54,999 | 14 (29) | 9 (26) | 5 (39) | |

| $55,000-$74,999 | 7 (15) | 6(17) | 1 (8) | |

| ≥$75,000 | 10 (21) | 6(17) | 4 (31) | |

| Missing | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Employment status | .188 | |||

| Employed for wages | 15 (31) | 10 (29) | 5 (39) | |

| Out of work 1 y or more | 4 (8) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Retired | 17 (35) | 12 (34) | 5 (39) | |

| Self-employed | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Unable to work | 9 (19) | 8 (23) | 1 (8) | |

| Homemaker | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | |

| Student | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | |

|

mean (SD)

|

||||

| Baseline hemoglobin A1c, % | 8.61 (1.18) | 8.62 (1.17) | 8.60 (1.23) | .959 |

Feasibility

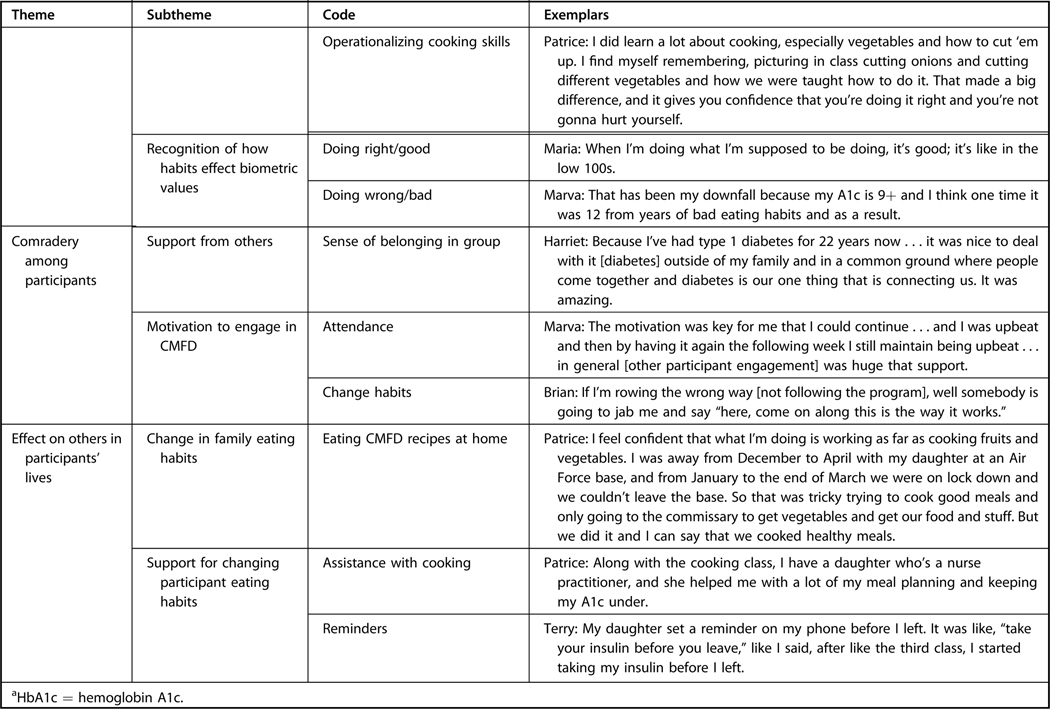

Feasibility-aligned themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes are provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Thematic coding schema of Cooking Matters for Diabetes (CMFD) focus groups by feasibility dimension.

Demand

In total, 425 patients came in contact with the study team as part of recruitment efforts. Fifty-four patients consented to the intervention and were randomized (12.7%) (Figure 5; available at www.jandonline.org). Many of the individuals not enrolled were interested in the intervention but could not participate due to work schedules, failure to qualify, lack of transportation, too great a distance to the study location, and disabilities that prevent cooking.

Figure 5.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for Cooking Matters for Diabetes. Those lost to follow-up failed to complete any surveys or hemoglobin A1c collection.

Forty-eight individuals attended at least 1 class. Reported reasons for randomized participants not attending any classes included moving from the geographic area, not understanding the incentive schedule, lacking transportation, and HbA1c decreasing to below the cutoff before starting the intervention. On average, participants attended 83% of classes. Forty-six percent (n = 22) of participants attended all 6 classes, 25% (n = 12) attended 5 classes, 21% (n = 10) attended 4 classes, 2 participants attended 3 classes, and 2 participants attended the first class only and both withdrew. Retention to the end of the intervention was 85% for survey completion and 90% for HbA1c measurements. Retention to the end of the follow-up period was 58% for survey completion and 46% for HbA1c measurements (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cooking Matters for Diabetes survey and hemoglobin A1c completion counts

| Completion of Measurements |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveys |

Hemoglobin A1c |

DHQ IIIa |

||||

| Variable | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention |

|

n (%)

b

|

||||||

| Baseline | 22 (100) | 26 (100) | 22 (100) | 26 (100) | 21 (100) | 26 (100) |

| Post | 17 (77) | 24 (92) | 20 (91) | 23 (88) | 7 (33) | 22 (85) |

| 3 mo | 12 (55) | 20 (77) | 9 (41) | 19 (73) | 11 (52) | 17 (65) |

| 6 mo | 13 (59) | 15 (58) | 13 (59) | 8(31) | 10 (48) | 14 (54) |

| 12 mo | 14 (64) | 14 (54) | 10 (45) | 12 (46) | 8 (38) | 8(31) |

DHQ III = Diet History Questionnaire III.29

Counts of people who completed all surveys, the DHQ III, or hemoglobin A1c measurement at each time point and percentages of baseline values.

Ninety-eight percent of exit survey respondents (n = 40) said that they would share what they learned with friends and family and 78% said they made the recipes taught in class at home.

After the follow-up period, 13 participants verbally consented to take part in focus groups. Of those participants, 4 were food insecure and 9 were food secure (Table 3; available at www.jandonline.org). When asked to rate their participation, most (62%) focus group participants rated themselves between 7 and 9 on a scale of 10, where 0 was no participation and 10 was high participation. Only food insecure participants rated themselves a 10. Participants interpreted higher participation as higher class attendance, engagement, and use of class principles at home. Food insecure focus group participants spoke highly of the food provisions received during the intervention, but food secure participants were less enthused and reported lower likelihood of using the food provisions.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of Cooking Matters for Diabetes focus group participants according to food security status

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 13) | Insecure (n = 4) | Secure (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

mean (SD)

|

|||

| Age, y | 56.6 (13.6) | 52.8 (9.64) | 58.3 (15.2) |

| Sex | |||

|

n (%)

|

|||

| Female | 11 (84) | 4 (100) | 7 (78) |

| Male | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 2. (22) |

| Race | |||

| African American | 6 (46) | 3 (75) | 3 (33) |

| More than 1 race | 2 (15) | 1 (25) | 1. (11) |

| White | 5 (39) | 0 (0) | 5 (56) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 12 (93) | 3 (75) | 9 (100) |

| Undisclosed | 1 (7) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Marital status | |||

| Divorced | 4 (31) | 2 (50) | 2 (22) |

| Living with a partner | 1 (8) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Married | 5 (39) | 1 (25) | 4 (44) |

| Never married | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) |

| Widowed | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

|

mean (SD)

|

|||

| No. of Children | 0.50 (1.17) | 0.50 (0.58) | 0.50 (1.41) |

|

n (%)

|

|||

| Missing | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

| Annual income | |||

| <$25,000 | 3 (23) | 1 (25) | 2 (22) |

| $25,000-$54,999 | 5 (39) | 2 (50) | 3 (33) |

| $55,000-$74,999 | 1 (8) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| ≥$75,000 | 4 (31) | 0 (0) | 4 (44) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed for wages | 5 (39) | 1 (25) | 4 (44) |

| Homemaker | 1 (8) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Retired | 5 (38.5) | 2 (50) | 3 (33) |

| Student | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

| Unable to work | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

|

mean (SD)

|

|||

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 8.60 (1.23) | 9.28 (1.23) | 8.30 (1.17) |

Acceptability

Focus group participants reported high acceptability related to their perceived satisfaction with and usefulness of the intervention. Focus group participants believed CMFD was a positive experience and wished the intervention had not ended. Terry reported, “I enjoyed the whole class.” Overwhelmingly, participants believed CMFD provided useful information and skills. Ryan said, “[the intervention] helped me to see myself, the way I was, and where I should be. It really helped me get down to where I should be.”

Facilitators of participation were instructors, setting, and provision of educational content applicable to diabetes management. Instructors were praised for being knowledgeable, engaging, and passionate about their work. Cici remarked, “They really wanted to teach us, and they really were interested in what our opinions were.” Participants appreciated the group setting and being in the company of peers. Participants learned techniques and recipes that could be used outside of the classroom. Although not every recipe was appreciated by all participants, Patrice, with agreement from others, expressed that the intervention showed her “the importance of fresh fruits and vegetables and incorporating some of that into my diet.” Provision of recipes and food facilitated participants’ understanding of the education delivered during sessions and also brought those lessons home for themselves and family. Participants appreciated that classes were offered in a community setting.

One barrier to participation was aversion to class recipes. Beth said that she “wish[ed] there were more [recipes] that weren’t Mexican or Tex-Mex.”

Implementation

Fidelity, as monitored by the CDCES, was 100%; all aspects of the curriculum were covered, including all indicators of standard 6 of the American Diabetes Association Education Review Criteria.21

Two primary subthemes emerged from the focus groups: refinements to intervention execution and improved resources for intervention delivery. Proposed intervention refinements included extending time for cooking and fraternizing, using “easy” recipes, and expanding types of instruction. Participants lamented not having enough time to complete intervention activities and engage with other participants. Vanessa said, “The class could have been 15 to 30 minutes longer, and I think that would have been nicer for the class to have been maybe two weeks longer to so that we could have spent more time learning and spent more time together getting to know each other.” Some requested recipes with fewer ingredients and shorter preparation time. Brian recommended that recipes “have no more than five ingredients . . . because some of them got just a tad bit complicated.” Participants suggested that other sources of education be used like nutritionists and learning from past participants. Laura explained, “it’s helpful when we’re able to see someone who has completed the program and who has found success with the program and that might provide some impetus and something for new participants to connect.”

Another suggestion was to allow choice of provided groceries. Carey remarked, “If [she] had like a grocery area that you could go pick up what you wanted,” then she might have used the provided food more at home.

Practicality

CMFD was funded by a $20,000 grant from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation and by billing participants’ insurance for DSMES. Share our Strength’s CM intervention received $10,000 for their involvement in CMFD. This included the cost of the food provisions. Other major expenditures were labor of the CDCES and principal investigator ($7,000) and cartridges to measure participants’ HbA1c ($1,600).

Limited Efficacy

Focus group participants perceived the intervention to be effective across the following 3 domains: improved diabetes management, camaraderie among participants, and effect on others in participants’ lives.

Focus group participants reported CMFD led to better control of HbA1c and body weight. Harriet stated, “Not only did this class create a positive effect for my view of diabetes and cooking . . . it had a positive feedback in my care for diabetes.” Participants also mentioned that intervention activities led to better ability to plan and cook meals. Cici described how her learning experience in CMFD prompted her to make dietary changes. She said, “I made that stir fry from the food that I got from the program, it was really delicious, so maybe we just incorporate that instead of buying that instant meal or fast food.” They recognized the effects of healthy meal choices, in line with concepts learned in CMFD. Another participant said, “I do have those tools. I’m able to pull myself back together.”

Participants built camaraderie among themselves, which was associated with reduction of isolation as a person living with diabetes and provision of motivation. Cici said, “We sat at the table with people that we didn’t know, and we developed relationships with those people. That was good, different walks of life and different things going on in everybody’s life, but we all came together on that common ground to learn.” No longer in isolation, participants began to change habits together. Brian explained, “It was a friendly camaraderie when you’re all sitting in that lifeboat together and you decide you better pull in the same direction.”

The intervention initiated a change in others in participants’ lives. Laura expressed, “I cook with my students now . . . I hope that I am transferring some of the things that I learned in our class on to the students who I work with as well.” Furthermore, dietary changes were impactful among the families. Patrice noted, “Along with the cooking class, I have a daughter who’s a nurse practitioner, and she helped me with a lot of my meal planning and keeping my A1c under, under control.”

DISCUSSION

We observed high feasibility of a multicomponent intervention, CMFD, which incorporated cooking-related skill-building, practical application of DSMES, and lesson-aligned food provisions.

Food insecure participants were more likely to report using the food provisions and making recipes from the cookbook at home. Our findings are in line with another study that found food insecure individuals improved more than food secure individuals after a diabetes education intervention.30 Food insecure participants in the present study also had higher HbA1c than the food secure participants at baseline. Knowing their glycemic control was poor may have led them to value the intervention more highly than their peers, as evidenced by their reported use of food provisions, their self-rating of participation, and their greater demand for a DSMES intervention, relative to food secure participants, based on focus group discussions.

Feedback from participants illuminated areas for improvement and areas where the study met patient needs. Although many criticized the short length of the class as an area for improvement, it is a testament to the quality of intervention implementation that participants wanted it to be longer. CMFD was 6 weeks long, which is longer than some randomized controlled trial cooking interventions,31,32 but shorter than others.33–35 In contrast, some participants in an 8-week mindfulness intervention with diabetes education for people with prediabetes reported wanting a shorter intervention length.36

Participants reported changing at-home behaviors after participation in this intervention. This is important because all of the participants had DSMES before enrolling in CMFD. The behavior change prompted by this intervention was change not prompted by standard of care DSMES. Participants also brought the lifestyle habits they learned in class home to their families, resulting in unintended positive effects of this intervention. Others have reported that family support is important for successful behavior change in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.16,37 The importance of social interaction between participants during a diabetes intervention has been reported in another study.38 Abbott and colleagues38 reported that some participants only attended their intervention for social reasons; they initially reported no desire to adopt healthier behaviors. Abbott and colleagues reported positive behavior change, even in those who expressed no interest in changing their habits.

CONCLUSIONS

CMFD, a practical application of DSMES and cooking intervention with lesson-aligned food provisions, showed high feasibility. Intervention utilization was highest among participants with food insecurity. Among all participants, acceptability was high and participants were mostly happy with the implementation of the intervention.

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT

Research Question: Is a diabetes self-management education and support cooking intervention feasible among diverse, urban-dwelling participants?

Key Findings:

The intervention was feasible according to the measured principles of demand, acceptability, implementation, practicality, and limited efficacy. Use of the intervention (demand) was highest among food insecure participants. portion (approximately 1 hour) and a hands-on cooking portion (approximately 1 hour), except for class number 5, which was an interactive grocery store tour. The DSMES portion covered all 9 indicators required by the American Diabetes Association.21,22 A CM instructor taught the cooking portion of the class, and the DSMES portion was taught by a registered dietitian nutritionist, who was also a certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES). A medical dietetics graduate student intern provided support for the intervention. Because the intervention followed DSMES guidelines, 1 hour of each of the 5 classes taught by the CDCES was billed to participants’ insurance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the staff and participants of Cooking Matters for Diabetes and all of the partners that made this project possible. Local Matters (local-matters.org) partnered in the design and delivery of the intervention, including the culinary instructor, cooking equipment, food provision, and Local Matters volunteers. The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Diabetes Education team provided the community facility in which Cooking Matters for Diabetes was delivered.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This study was funded by the Diabetes Care and Education Dietetics Practice Group Karen Goldstein Memorial Grant from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants UL1TR002733 and K08CA245208. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT04152811.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

Jennifer C. Shrodes, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

Amaris Williams, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

Timiya S. Nolan, The Ohio State University College of Nursing, Columbus..

Jessica N. Radabaugh, Division of Medical Dietetics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

Ashlea Braun, Department of Nutritional Sciences, School of Education and Human Sciences, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater; Division of Medical Dietetics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

David Kline, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem NC..

Songzhu Zhao, Center for Biostatistics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine Columbus.

Guy Brock, Department of Biomedical Informatics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

Jennifer A. Garner, The School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, The Ohio State University College of Medicine and The John Glenn College of Public Affairs, The Ohio State University, Columbus..

Colleen K. Spees, Division of Medical Dietetics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

Joshua J. Joseph, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus..

References

- 1.Menke A, Orchard TJ, Imperatore G, Bullard KM, Mayer-Davis E, Cowie CC. The prevalence of type 1 diabetes in the United States. Epidemiology. 2013;24(5):773–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcome. s: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S48–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: A joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1372–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers MA, Bardsley JK, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in adults with type 2 diabetes: A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association, the Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of PAs, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, and the American Pharmacists Association. Sci Diabetes Self-Manag Care. 2021;47(1):54–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franz MJ, MacLeod J, Evert A, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition Practice guideline for type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults: Systematic review of evidence for medical nutrition therapy effectiveness and recommendations for integration into the nutrition care process. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):1659–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs Early K, Stanley K. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: The role of medical nutrition therapy and registered dietitian nutritionists in the prevention and treatment of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(2):343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: A consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):731–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts SA, Yelverton D. An expanded paradigm of primary care diabetes chronic disease management. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17(6):677–679. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andary R, Fan W, Wong ND. Control of cardiovascular risk factors among US adults with type 2 diabetes with and without cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(4):522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Wexler DJ, Huskey KW, Wee CC. Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3093–3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, Tschann J, Fernandez A. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Definitions of food security. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; Published 2019. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iacovou M, Pattieson DC, Truby H, Palermo C. Social health and nutrition impacts of community kitchens: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(3):535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soliah LAL, Walter JM, Jones SA. Benefits and barriers to healthful eating: What are the consequences of decreased food preparation ability? Am J Lifestyle Med. 2012;6(2):152–158. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott P, Davison J, Moore L, Rubinstein R. Barriers and enhancers to dietary behaviour change for Aboriginal people attending a diabetes cooking course. Health Promot J Austr. 2010;21(1):33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archuleta M, VanLeeuwen D, Halderson K, et al. Cooking schools improve nutrient intake patterns of people with type 2 diabetes. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(4):319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrne C, Kurmas N, Burant CJ, et al. Cooking classes: A diabetes self-management support intervention enhancing clinical values. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(6):600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasgupta K, Hajna S, Joseph L, Da Costa D, Christopoulos S, Gougeon R. Effects of meal preparation training on body weight, glycemia, and blood pressure: Results of a phase 2 trial in type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams A, Shrodes JC, Radabaugh JN, et al. Outcomes of Cooking Matters for Diabetes: A 6-week randomized, controlled cooking and diabetes self-management education intervention. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122:00–00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al. 2017 National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(10):1409–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association’s Education Recognition Program Review Criteria and Indicators. 10th ed. American Diabetes Association; 2017. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://professional.diabetes.org/files/media/review_criteria_10th_edition_revised_9.2019-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Household Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design, with Screeners. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; Published 2012. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8271/hh2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diet History Questionnaire III. National Cancer Institute. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/dhq3/

- 30.Lyles CR, Wolf MS, Schillinger D, et al. Food insecurity in relation to changes in hemoglobin A1c, self-efficacy, and fruit/vegetable intake during a diabetes educational intervention. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1448–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGorrian C, O’Hara MC, Reid V, Minogue M, Fitzpatrick P, Kelleher C. BMI change in Australian cardiac rehabilitation patients: Cookery skills intervention versus written information. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(2):228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poelman MP, de Vet E, Velema E, de Boer MR, Seidell JC, Steenhuis IHM. PortionControl@HOME: Results of a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a multi-component portion size intervention on portion control behavior and body mass index. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(1):18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenlee H, Gaffney AO, Aycinena AC, et al. ¡Cocinar Para Su Salud!: Randomized controlled trial of a culturally based dietary intervention among Hispanic breast cancer survivors. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(5):709–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carmody J, Olendzki B, Reed G, Andersen V, Rosenzweig P. A dietary intervention for recurrent prostate cancer after definitive primary treatment: Results of a randomized pilot trial. Urology. 2008;72(6): 1324–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters NC, Contento IR, Kronenberg F, Coleton M. Adherence in a 1-year whole foods eating pattern intervention with healthy post-menopausal women. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2806–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods-Giscombe CL, Gaylord SA, Li Y, et al. A mixed-methods, randomized clinical trial to examine feasibility of a mindfulness-based stress management and diabetes risk reduction intervention for African Americans with prediabetes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:e3962623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu J, Mion LC, Tan A, et al. Perceptions of African American adults with type 2 diabetes on family support: Type, quality, and recommendations. Sci Diabetes Self-Manag Care. 2021;47(4):302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abbott PA, Davison JE, Moore LF, Rubinstein R. Effective nutrition education for Aboriginal Australians: Lessons from a diabetes cooking course. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MyPlate. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www.myplate.gov/