Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) comprises a spectrum of diseases ranging from unstable angina (UA), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI) and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Treatment of ACS without STEMI (NSTEMI-ACS) can vary, depending on the severity of presentation and multiple other factors.

OBJECTIVE:

Analyze the NSTEMI-ACS patients in our institution.

DESIGN:

Retrospective observational

SETTING:

A tertiary care institution with accredited chest pain center

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

The travel time from ED booking to the final disposition for patients presenting with chest pain was retrieved over a period of 6 months. The duration of each phase of management was measured with a view to identify the factors that influence their management and time from the ED to their final destination. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Travel time from ED to final destination

SAMPLE SIZE:

300 patients

RESULTS:

The majority of patients were males (64%) between 61 and 80 years of age (45%). The median disposition time (from ED booking to admission order by the cardiology team) was 5 hours and 19 minutes. Cardiology admissions took 10 hours and 20 minutes from ED booking to the inpatient bed. UA was diagnosed in 153 (51%) patients and non-STEMI in 52 (17%). Coronary catheterization was required in 79 (26%) patients, 24 (8%) had coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and 8 (3%) had both catheterization and CABG.

CONCLUSION:

The time from ED booking to final destination for NSTEMI-ACS patients is delayed due to multiple factors, which caused significant delays in overall management. Additional interventional steps can help improve the travel times, diagnosis, management and disposition of these patients.

LIMITATIONS:

Single center study done in a tertiary care center so the results from this study may not be extrapolated to other centers.

INTRODUCTION

The chief complaint of chest pain alone affects 20-40% of the worldwide population.1 In the United States, chest pain accounts for about 8 million adult visits to the ED, becoming the second most frequent cause of emergency department (ED) visits after abdominal pain.2–4 Cardiovascular disease incidence is increasing in developing countries over the last decade.5,6

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) includes three ischemic subtypes; unstable angina (UA), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI) and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).7 STEMI is a leading cause of death in the U.S,8–10 followed by non-STEMI and UA (NSTEMI-ACS). It is imperative to distinguish between STEMI and NSTEMI as they are managed differently; those with STEMI require urgent coronary intervention while those with NSTEMI-ACS are managed after stratifying their risk.11–14 While the incidence of STEMI has decreased over recent years, the incidence of NSTEMI has increased slightly.15

Studies have shown that rapid risk stratification using scoring tools and timely treatment improve outcomes for ACS patients, but most of those studies began in the 1990s and were targeting STEMI patients and successfully developed diagnostic tools and protocols for these patients only.16,17

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ACS.18,19 As indicated by Butt et al conducted in Saudi Arabia, a door-to-balloon time of <90 minutes for those undergoing PCI was established as per the AHA devised ACS protocol.13

The “Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines” (CRUSADE) study demonstrated a significant association between adhering to recommended guidelines and in-hospital mortality. However, it did not evaluate any association between time-based guidelines. Despite several studies indicative of adherence to the AHA/ACS guideline, ED physicians still struggle to fulfill these criteria.4,20

The aim of our study was to gather “time intervals” as dependable variables to evaluate patient and system factors that influence NSTEMI-ACS patient travel times from the ED to their final destination in the hospital. These factors could include patient clinical state, ECG changes, troponin levels, risk stratification and associated co-morbidities. The ED diagnosis, cardiology response times, and management can also be variable in this group of patients. They may end up in a catheter lab, coronary care unit (CCU) or be discharged if they survive. We also attempted to identify any existing association between the recommended time-based guidelines and our quality indicators. We also evaluated delays in the time from ED booking in patients with NSTEMI-ACS and provided recommendations to help avoid these delays.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study included patients who presented at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre from October 2020 to March 2021 with the chief complaint of chest pain categorized as “unspecified chest pain”, “unstable angina,” “acute sub endocardial myocardial infarction,” “atherosclerotic heart disease of unspecified vessel,” “unspecified angina pectoris,” “angina pectoris with documented spasm,” “other forms of angina pectoris” and “other chest pain.” Electronic patient medical records were obtained through the health information technology affairs department. Our study was approved by the research advisory council (RAC #2211112) of the hospital. Since the study was retrospective, patient consent was not required. Data was retrieved from the secured password protected electronic medical records and patients were not contacted for any missing information. Patient confidentiality was maintained.

Data regarding the time intervals of the patients' trip from ED booking, consultation and admission was retrieved after verifying the diagnosis using the International Classification Of Diseases criteria recommended by the WHO and used by our hospital. This initial data was manually analyzed and narrowed down to 300 patients with a single hospital admission within our designated study time period. The excluded patients had a final diagnosis of non-cardiac chest pain.

This data was transferred to a sheet, reflecting the patient travel with timestamps in minutes. The recorded times started from ED registration, consultation order for cardiology, consultation notes by cardiology, medication prescription and administration, admission decision time and time of physical transfer of patient to a hospital bed. The number of patients with different diagnoses within the NSTEMI-ACS spectrum and procedures performed were also recorded. Times are shown as hours:minutes:secconds

The data were analyzed using statistical software (JMP Version 14.0.0). Categorical data was represented by numbers and percentages, while the median and the interquartile range were used to represent the averages because the data values within this study were skewed and there were clear outliers. Graphs were done using R software (version 2023.09.1+494).

RESULTS

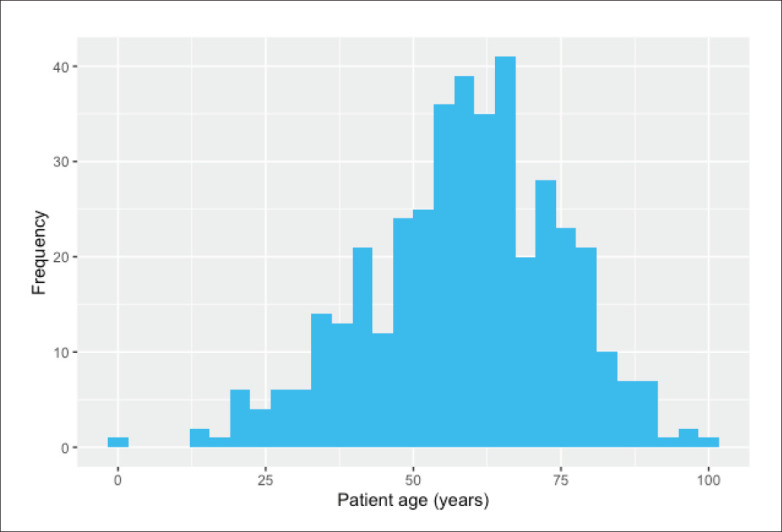

Most patients were males (n=191, 64%) between the ages of 61-80 years (45% with a median of 60 (21) years) (Figure 1). Most were self-referred (n=240, 80%). Presenting symptoms included chest pain alone (41.7%), chest pain and shortness of breath (20.3%), shortness of breath alone (12.7%) and others (25.3%) including atypical symprtoms such as epigastric pain, back pain, and generalized fatigueability. Delays happened in all domains of our patient management starting from ER consultation with cardiolgy, prescribing and dispensing medications including arrival to an appropriate clinical destination (Tables 1 and 2). ED diagnosis time (time from ED booking to cardiology consultation order) was 2:30. Consultation time (time from cardiology team consultation to cardiology documentation) was 1:14. UA was the diagnosis in 153 cases (51%), “low risk ACS” in 95 (32%), and non-STEMI in 52 (17%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patient ages (n=300).

Table 1.

Number of delays for NSTE-ACS patients in the emergency department (n=300). Delays were determined by specific time periods for such as cardiology consultation from ER should be done within 1/2 hour from the time of diagnosis.

| Request for cardiology consultation by ER | 281 (93.7) |

| Consultation notes by cardiology | 226 (75.3) |

| Number of patients receiving aspirin | 261 (87.0) |

| Number of patients receiving clopidogrel or ticagrelor | 197 (65.7) |

| Number of patients receiving heparin or enoxaparin | 248 (82.7) |

| Number of patients receiving nitroglycerine | 65 (21.7) |

| Number of patients receiving morphine | 26 (8.7) |

| Received all medications (Aspirin & clopidogrel or ticagrelor & heparin or enoxaparin & ntroglycerine or morphine) | 49 (16.3) |

| Patients subjected to catheterization | 79 (26.3) |

| Cardiac surgery performed | 24 (8.0) |

| Catheterization laboratory & cardiac surgery performed | 8 (2.7) |

Data are numbers (percentage).

Table 2.

NSTE-ACS pathway durations from the department of emergency medicine to the cardiac catheterization laboratory.

| Number (%) | Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis time (From EM registration time to cardiology consultation order) | 275 (91.7) | 2:37:31 | 2:58:45 |

| Consultation time (From the cardiology consultation order to cardiology consult notes in integrated electronic patient system | 201 (67.0) | 1:14:28 | 2:02:33 |

| Aspirin prescription time (From arrival to presen ption time) | 263 (87.7) | 4:31:59 | 5:36:01 |

| Aspirin administration time (From prescription to administration time) | 261 (87.0) | 1:50:48 | 11:39:59 |

| Clopidogrel prescription time (From arrival to prescription time) | 186 (62.0) | 5:58:51 | 5:03:51 |

| Clopidogrel administration time (From prescription to administration time) | 184 (61.3) | 2:21:48 | 10:23:26 |

| Heparin prescription time (From arrival to prescription time) | 123 (41.0) | 5:43:59 | 5:56:07 |

| Heparin administration time (From prescription to administration time) | 122 (40.7) | 2:29:57 | 5:51:09 |

| Nitroglycerin prescription time (From arrival to prescription time) | 101 (33.7) | 5:13:47 | 18:50:31 |

| Nitroglycerin administration time (From prescription to administration time) | 65 (21.7) | 0:38:32 | 1:59:46 |

| Morphine prescription time (From arrival to prescription time) | 30 (10.0) | 6:00:13 | 47:23:17 |

| Morphine administration time (From prescription to administration time) | 26 (8.7) | 1:25:40 | 3:41:56 |

| Disposition order time (From arrival to admission order done by the cardiology team) | 300 (100.0) | 5:19:10 | 3:53:29 |

| Admission time (From admission order to physical presence in the bed) | 300 (100.0) | 10:20:12 | 6:26:05 |

| Catheterization laboratory time (From arrival to catheterization laboratory) | 79 (26.3) | 28:45:01 | 51:01:05 |

| Cardiac surgery time (From arrival to cardiac surgery) | 24 (8.0) | 222:30:15 | 265:11:32 |

Median and IQR in hours:minutes:seconds.

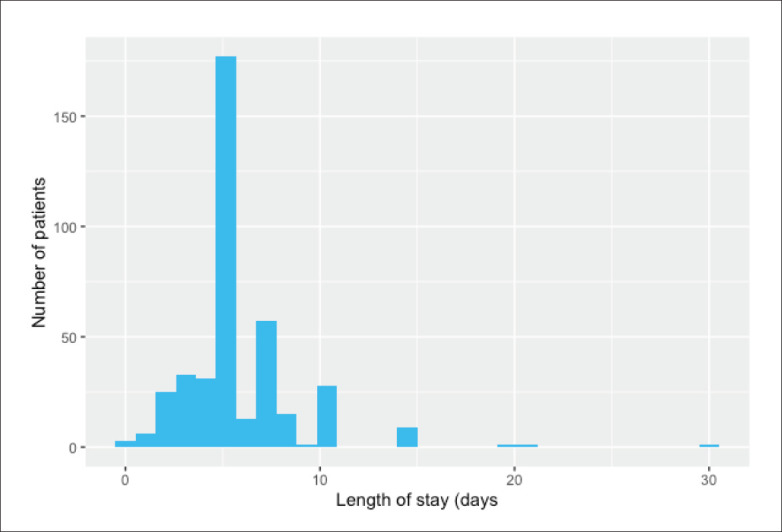

Two hundred and nine (70%) were admitted to a standard bed, 49 (16%) to the coronary care unit (CCU) and 42 (14%) admitted on a monitored bed (Table 3). The maximal treatment for NSTEMI-ACS (i.e. two anti-platelets aspirin, Plavix [clopidogrel] or ticagrelor), heparin or enoxaparin, nitroglycerine or morphine) was received by 49 (16%). Seventy-nine (26%) had coronary catheterization, 24 (8%) had coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and 8 (3%) had both catheterization & CABG. Disposition order time (from ED arrival to admission order by cardiology) was 5:19. Admission time (from arrival to physical presence on the bed) was 10:20. The median (IQR) length of hospital stay was 5 (2) days (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Patients with an NSTE-ACS diagnosis in the emergency department (n=300).

| Responses | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Less than 40 | 25 (8.3) |

| 40-60 | 118 (39.3) |

| 61-80 | 134 (44.7) |

| Over 80 | 23 (7.7) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 109 (36.3) |

| Male | 191 (63.7) |

| Mode of admission | |

| Ambulance | 56 (18.7) |

| Self-referral | 240 (80.0) |

| Others | 4 (1-3) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Low risk ACS | 95 (31.7) |

| NSTEMI | 52 (17.3) |

| Unstable angina | 153 (51.0) |

| Admission unit | |

| CCU | 49 (16.3) |

| MICU | 2 (0.7) |

| Monitored bed | 40 (13.3) |

| Standard bed | 209 (69.7) |

Data are number (percentage).

Figure 2.

Length of hospital stay (n=295; 4 values missing and one value about 100 days not shown).

DiSCUSSiON

Most studies evaluating NSTEMI-ACS patients observed no specificity in clinical presentation. Chien et al found that less than 40% of elderly patients presented with chest discomfort,21 while Gilutz et al found no correlation between clinical presentation and guideline adherence, they noted decreased physician attention towards patients presenting with angina equivalents.17 This ambiguity in presentation was a direct source of missed or delayed diagnosis of NSTEMI-ACS.22,23

A study done in an ED revealed that only 5.1% patients with chest pain were diagnosed as ACS.24 Another study showed, only 5 of 109 NSTEMI-ACS patients presented typically in the ED.25 The majority of the NSTEMI-ACS presentation in our study population was isolated chest pain accounting for around 42%, while 25% had chest pain associated with shortness of breath. The NSTEMI-ACS patients' symptoms can be typical angina which presents as substernal pain, squeezing, heavy or suffocating chest pain with variable radiation to the jaw, neck, or arm. Atypical angina or angina equivalent could present as pleuritic pain, epi-gastric discomfort, or back pain.23

A retrospective trial conducted on 4167 patients showed a 51.7% prevalence of atypical symptoms in NSTEMI-ACS patients.26 The latest AHA/ACC guidelines recommend heightened awareness for elderly (>75 years), as ACS may present with syncope, mental impairment, abdominal pain, or unexplained fall, together with chest pain.27–30 Numerous other studies describe difficulties in identifying atypical presentations of NSTEMI-ACS. Our study constituted a mix of presentations in about 25% of the study population. These patients presented with variable symptoms, such as abdominal pain, back pain, palpitations, and vomiting. This could also explain the delayed ED diagnosis in our study (Table 1). ED to cardiology consultation time (1:14, IQR 2:2) also could be explained due to the atypical presentations (Tables 1 and 2). Identifying these symptoms early can influence management especially in pre-hospital settings and also prevent door to treatment delays.31,32

Various risk stratification scores such as TIMI, HEART, PURSUIT, GRACE, Sanchis, Florence and FRISC are used to classify patients with different types of cardiac chest pain. However, the HEART score is exclusively used for NSTEMI-ACS patients.6 We use the HEART score in our ED but not all patients are scored due to the atypicality of presentation.

In-hospital adherence to NSTEMI-ACS guidelines has been evaluated in many studies26,27 with a few focusing on the first few hours of ED management.28,29,33 Studies have reported overall poor adherence to the NSTEMI-ACS guidelines17,34 with the main hindrance due to language barriers,17 delayed troponin results (100 minutes),33 poor documentation of cardiac history.35–37 Poor documentation has also been reported to be associated with considerably high mortality in NSTEMI-ACS populations.37

Understanding these time intervals and establishing a standard is not only beneficial for patients but also prevents the increased clinical workload on ED physicians and consequent overcrowding.38–40

The AHA/ACC introduced formal standards for ECG readout time and lab turnaround time in their framework of ACS management. However, there have been no reported standards for timestamps of a patient's ED travel time. In January 2012, the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services asked hospitals to report performance in an attempt to adopt standards.33–35 Our study explored multiple timestamps for NSTEMI-ACS cases such as time to diagnosis after ED presentation, medication prescription and administration, cardiology consultation and transfer to an inpatient bed/CCU as quality initiatives for efficient management of NSTEMIACS patients.

Studies have reported delayed ECG readout times,41 laboratory and therapeutic turnaround time as reasons for delayed management of NSTEMI-ACS.19,42 Adherence to the ACS guidelines was seen in less than 50% of the ED visits.34,43 In our study, we did not measure ECG readout times or laboratory turnaround times but we have recorded the therapeutic turnaround times for the common medications used for NSTEMI-ACS. We noticed a significant delay in prescribing (median 4:31, IQR 5:36) and administering (median 1:51, IQR 11:39) aspirin. Similar delays were recorded for clopidogrel and heparin (Table 2). Nitroglycerine and morphine time prescription durations were also variable. Given that nitroglycerine is the standard administration in cases of acute chest pain, we noted that it was used in only 21% of our patients. This could be due to various reasons including the clinician's decision, or lack of chest pain at the time of presentation. Not all patients had the physicians' prescription recorded in the notes. This could be due to failure of the physicians to record verbal orders to nurses. We only recorded those patients as having received medications, who had the time recorded for administration. The administration of clopidogrel and ticagrelor were counted together. Similarly, the heparin and enoxaparin administration were also counted together.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) of aspirin and ticagrelor/prasugrel is a standard in NSTEMI-ACS cases as per the PLATO44 and TRITON TIMI-3845 trials. European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines prefer prasugrel for NSTEMI-ACS cases proceeding to percutaneous coronary intervention over ticagrelor.46 Clopidogrel is selected in cases of ticagrelor/prasugrel contraindications, increased risk of bleeding and non-availability.46 The ISAR REACT 5 trial compared the superiority of prasugrel vs ticagrelor in NSTE-ACS patients, due to a decreased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and death without raising risk of bleeding.47 In addition, those with preexisting bleeding risk remained within risk, without any impact on efficacy or safety of ticagrelor or prasugrel.48 Another study used the PRECISE-DAPT score to choose between ticagrelor or prasugrel. They also reported overall better response from prasugrel for a score >25 in major adverse cardiac events and a clinical benefit compared to ticagrelor 1 year after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).49 However, ticagrelor decreased inflammatory cytokines and circulating endothelial progenitor cells in cases of diabetic NSTEMI ACS patients.50

Further evaluation of ACS for PCI based on optical coherence tomography (OCT) and Fractional flow reserve (FFR) guidance51 was assessed by the FORZA trial. They concluded that using OCT for angiography for intermediate coronary lesions patients decreased the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events or angina risk.52 A publication from the Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network (ACTION) Registry reported that 11.5% of patients presenting with NSTEMI-ACS in 2009, underwent CABG compared with 43.6% of patients who underwent PCI and 76.2% underwent angiography.53 In our study, 26.3% were subjected to catheterization (PCI) and 8% underwent CABG. However, data on completeness of revascularization could not be retrieved. We were also unable to analyze the subgroup which was subjected to the interventional procedures.

All the patients in our study consulted with the cardiology team in the ED. The consultation criteria takes into consideration clinical assessment, in conjunction with the risk depicted by the HEART score. Although all of our study patients were admitted, 63% were discharged home with medications alone, after a short period of admission with booked outpatient investigations.

The term a “low risk ACS” was perhaps a misnomer as the patients also were admitted by the cardiology team. This could be due to a high index of clinical suspicion, lack of senior cardiology decision making within the ED (which happens out of hours) or unidentified factors. Our tertiary care center receives a highly complex group of patients, leading to a lower threshold of admission.

Quality initiatives have primarily focused on decreasing the time to interventions in patients with STEMI. The diagnosis or rule-out of NSTEMI-ACS is equally important. With a more subtle presentation and gradual clinical manifestation, clinical evaluation can be prolonged due to diagnostic uncertainty and complexity.30,53

Systems-based improvements are more difficult to design and implement for NSTEMI-ACS, as the evaluation period of these patients is longer, more resource intensive, and dependent on intra-hospital factors. The duration of ED evaluation can be problematic, as it makes the diagnosis and treatment of NSTEMI-ACS patients more susceptible to fluctuations in ED (which in turn is dependent on hospital occupancy, provider handovers, and time-varying demands on ED and hospital resources). Our study measured the variability in NSTEM-ACS care processes at an accredited chest pain center and highlighted patient factors (e.g. variable clinical presentations), ED delays, and hospital factors.

Research has shown that patient socioeconomic factors can also affect care quality perhaps due to conscious or subconscious biases of healthcare providers.38 Factors such as age<65, female gender, non-white race, non-English language, and insurance type have been determined as the cause of significant delays in time intervals in more than one study.4,43 Generally, patients who receive a higher Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) triage category in the ED have shorter travel times, as clinicians will prioritize those patients. Yoon et al found that NSTEMI-ACS patients with lower triage categories had the longest wait times for physicians and nurses and the longest ED length of stay (LOS).39 In our study, ED median diagnosis time was 2:37. Atypical clinical presentations can lead clinicians to a wrong diagnostic pathway.40 We could not do a subgroup analysis to associate this delay to atypical clinical presentations group.

Previous research has shown that diagnostic imaging, laboratory tests, and specialty consultations are associated with a longer LOS.39 Smart use of related ancillary services can facilitate timely NSTEMI-ACS care (e.g., physicians starting treatment before the troponin results become available).40 Some studies found better turnaround times in NSTEMI-ACS patients, when a physician was included in the triage, point-of-care testing (POCT) for troponin was used and a cardiologist was based in the ED.19,41 Published research performed in the ED showed physician triage reduced ED LOS by 37 minutes.41 A similar “on call system” as used for STEMI may help reduce the time for NSTEMI patients as well.19 A recent multicenter cost-benefit study of true POCT in the ED found that its use increased the proportion of patients successfully discharged home and reduced the median hospital LOS, but did not reduce costs.19,42

Factors characterizing ED and hospital crowding were significantly associated with delays in ACS care. ED crowding and/or increasing demands on critical resources prolonged patient travel times.30,43,53 Patients who were admitted on days with a crowded ED had 5% greater odds of inpatient death.54 Increasing occupancy in the catheterization laboratory was a major driver of ED boarding for cardiac patients.55 Studies also demonstrated that variability in elective cardiac surgery schedules had a significant adverse effects on ED boarding times.56

The results of our study show four predominant factors, which affected the travel times of the emergency NSTEMI-ACS care pathway (Table 2):

Prolonged door to ED physician time (triaging issues: delayed or under-triaging), atypical clinical presentation, lack of clinical examination space within ED);

Delayed consultation with cardiology team by ED (lack of patient streaming to a cardiology assessment area, delay in answering phone calls by speciality due to competing priorities in CCU, waiting for serial troponins);

Hospital processes (no presence of cardiology team decision makers within ED, no designated beds within ED for assessing chest pain patients);

Over-crowding and resource demand factors (high ED patient volume and less availability of hospital in-patient beds leading to boarding)

The current ACS guidelines recommend serial ECG and troponin every 3–6 hours.55 In Lehmacher et al, of 1675 patients in the study, 25 (1.5%) patients showed new ischemic changes in the ECG after 3 hours, 92 (5.5%) patients had ischemic signs in the admission ECG which were resolved in the second ECG, and in 237 (14.1%) patients ischemic signs were documented in both performed ECGs.56 Serial ECGs and troponins are widely practiced in ED to rule out NSTEMI-ACS, which adds to significant increase in ED LOS. Besides cardiac troponins, there are new algorithms that also in-corporate B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), NT-proBNP, which promises a faster diagnosis and ruling out MI,57 hence leading physicians to hold patients in the ED for longer periods, awaiting laboratory results. Gilutz et al recorded medication delivery for NSTEMI-ACS patients was significantly delayed in elderly, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and GRACE score >140 patients. The delays were attributed to physician's misconceptions.17

Many ED patients will be hospitalized for further investigation due to the uncertainty of the underlying source of their chest pain. Such an approach by the ED is to mitigate the risk of discharging 10% to 30% of these patient with atypical ACS.58,59 Despite this approach, an average of 2% to 3% of patients with AMI are unintentionally discharged from EDs in the United States.60,61 This challenges the ED physician as to how to treat the NSTEMI-ACS in a timely manner, while discharging the rest for outpatient investigations and management. This might be the reason for a higher ED consultation rate and consequent admission for our study patients.

In our study, self-referral was the most common (80%) mode of transfer (Table 3). This is an important finding in the pre-hospital delay in ACS patients. It is also a frequent finding in the majority of the ACS registries within the Arab and Middle East countries,62–65 conveying the current lack and importance of public awareness for rapid action to improve outcome for those high-risk ACS patients. Despite the availability of advanced ambulance transfer systems, the majority of these high-risk patients suffer unfortunately due to the delay associated with self-transfer, which is due to insufficient awareness and education.

Chest pain units in EDs are needed to provide safe and high quality care, reduce unsafe discharges, and allow appropriate hospital admissions in a cost-effective way.66 This can be achieved with the use of joint diagnostic protocols by ED and cardiology physicians, who have a specialized interest in this area.54,67

In conclusion, the needs are for 1) an ED-based protocol driven management of NSTEMI-ACS, similar to that of STEMI; 2) dedicated chest pain beds within the ED to streamline suspected patients from ED triage; 3) and chest pain units based in close vicinity of the ED for patients needing cardiology consultation and assessment (the ED senior decision makers should be able to send patients to this area without the need to wait for cardiology team members to come to ED); 4) cardiology physician presence in the ED and the rapid availability of POCT troponin will help with relatively lesser acute patients not needing to go to the chest pain unit; and 5) the early availability and prioritization of beds for NSTEMI-ACS patients, needing the catheter lab, CABG or a monitored CCU bed.

The limitations of this study is that it was an observational study with a relatively small sample size and retrospective data over 6 months, representing a single center study done in an accredited chest pain tertiary care center. The results cannot be extrapolated to other non-accredited centers.

Funding Statement

Funding: None.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deharo P, Ducrocq G, Bode C, Cohen M, Cuisset T, Mehta S, et al. Timing of Angiography and Outcomes in High-Risk Patients With Non–ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction Managed Invasively. Archive Ouverte Hal [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2023]. Available from: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01744667/document [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Denlinger LN, Keeley EC.. Medication Administration Delays in Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Analysis of 1002 Patients Admitted to an Academic Medical Center. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2018. Jun;17(2):73–76. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000142 PMID: 29768314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erol MK, Kayıkçıoğlu M, Kılıçkap M, Güler A, Yıldırım A, Kahraman F, et al. Treatment delays and in-hospital outcomes in acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide study. Anatol J Cardiol. 2020. Nov;24(5):334–342. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2020.98607 PMID: 33122486; PMCID: PMC7724394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.France DJ, Levin S, Ding R, Hemphill R, Han J, Russ S, et al. Factors Influencing Time-Dependent Quality Indicators for Patients With Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Patient Saf. 2020. Mar;16(1):e1–e10. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000242 PMID: 26756723; PMCID: PMC4940339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg MR, Bond WF, MacKenzie RS, Lloyd R, Bindra M, Rupp VA, et al. Gender disparity in emergency department non-ST elevation myocardial infarction management. J Emerg Med. 2012. May;42(5):588–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.07.003. Epub 2010 Oct 2 PMID: 20884159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma CP, Wang X, Wang QS, Liu XL, He XN, Nie SP.. A modified HEART risk score in chest pain patients with suspected non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016. Jan;13(1):64–9. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.01.013 PMID: 26918015; PMCID: PMC4753014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stehli J, Martin C, Brennan A, Dinh DT, Lefkovits J, Zaman S.. Sex Differences Persist in Time to Presentation, Revascularization, and Mortality in Myocardial Infarction Treated With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019. May 21;8(10):e012161. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012161 PMID: 31092091; PMCID: PMC6585344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tekin K, Cagliyan CE, Tanboga IH, Balli M, Uysal OK, Ozkan B, et al. Influence of the Timing of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention on Clinical Outcomes in Non-STElevation Myocardial Infarction. Korean Circ J. 2013. Nov;43(11):725–30. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2013.43.11.725. Epub 2013 Nov 30 PMID: 24363747; PMCID: PMC3866311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tymchak W, Armstrong PW, Westerhout CM, Sookram S, Brass N, Fu Y, et al. Mode of hospital presentation in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: implications for strategic management. Am Heart J. 2011. Sep;162(3):436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.011. Epub 2011 Aug 9 PMID: 21884858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yudi MB, Ajani AE, Andrianopoulos N, Duffy SJ, Farouque O, Ramchand J, et al.; Melbourne Interventional Group. Early versus delayed percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Coron Artery Dis. 2016. Aug;27(5):344–9. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000374 PMID: 27097120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zègre-Hemsey JK, Burke LA, DeVon HA.. Patient-reported symptoms improve prediction of acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department. Res Nurs Health. 2018. Oct;41(5):459–468. doi: 10.1002/nur.21902. Epub 2018 Aug 31 PMID: 30168588; PMCID: PMC6195799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paichadze N, Afzal B, Zia N, Mujeeb R, Khan M, Razzak JA.. Characteristics of chest pain and its acute management in a low-middle income country: analysis of emergency department surveillance data from Pakistan. BMC Emerg Med. 2015;15 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S13. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-15-S2-S13. Epub 2015 Dec 11 PMID: 26691439; PMCID: PMC4682378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butt TS, Bashtawi E, Bououn B, Wagley B, Albarrak B, Sergani HE, et al. Door-to-balloon time in the treatment of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2020. Jul-Aug;40(4):281–289. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2020.281. Epub 2020 Aug 6 PMID: 32757982; PMCID: PMC7410222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J. 2019. Jan 14;40(3):237–269. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy462 PMID: 30165617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grech ED, Ramsdale DR.. Acute coronary syndrome: unstable angina and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. BMJ. 2003. Jun 7;326(7401):1259–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1259 PMID: 12791748; PMCID: PMC1126130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedayati T, Yadav N, Khanagavi J.. Non-ST-Segment Acute Coronary Syndromes. Cardiol Clin. 2018. Feb;36(1):37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.08.003 PMID: 29173680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilutz H, Shindel S, Shoham-Vardi I.. Adherence to NSTEMI Guidelines in the Emergency Department: Regression to Reality. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2019. Mar;18(1):40–46. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000165 PMID: 30747764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Brooks NH, Fesmire FM, Lambrew CT, Landrum MB, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures; Writing Committee to Develop Performance Measures on ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Performance Measures on ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction). Circulation. 2006. Feb 7;113(5):732–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.172860. Epub 2006 Jan 3 PMID: 16391153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE Jr, et al.; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction); American College of Emergency Physicians; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. Aug 14;50(7):e1–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Mar 4;51(9):974 PMID: 17692738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Mulgund J, De-Long ER, Lytle BL, Brindis RG, et al. Association between hospital process performance and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2006. Apr 26;295(16):1912–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1912 PMID: 16639050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chien DK, Huang MY, Huang CH, Shih SC, Chang WH.. Do elderly females have a higher risk of acute myocardial infarction? A retrospective analysis of 329 cases at an emergency department. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016. Aug;55(4):563–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.06.015 PMID: 27590383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canto AJ, Kiefe CI, Goldberg RJ, Rogers WJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, et al. Differences in symptom presentation and hospital mortality according to type of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2012. Apr;163(4):572–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.01.020. Epub 2012 Mar 29 PMID: 22520522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, Califf RM, Cheitlin MD, Hochman JS, et al. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction–summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002. Oct 2;40(7):1366–74. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02336-7 PMID: 12383588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canto JG, Fincher C, Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Li Q, Funkhouser E, et al. Atypical presentations among Medicare beneficiaries with unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2002. Aug 1;90(3):248–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02463-3 PMID: 12127612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsia RY, Hale Z, Tabas JA.. A National Study of the Prevalence of Life-Threatening Diagnoses in Patients With Chest Pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2016. Jul 1;176(7):1029–32. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2498 PMID: 27295579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta RH, Roe MT, Chen AY, Lytle BL, Pollack CV Jr, Brindis RG, et al. Recent trends in the care of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the CRUSADE initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006. Oct 9;166(18):2027–34. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.2027 PMID: 17030838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metting A, Binz D, Colbert CY, Song J, Chiles C, Mirkes C.. Comparison of documentation and evidence-based medicine use for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction among cardiology, teaching, and nonteaching teams. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015. Jul;28(3):312–6. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2015.11929259 PMID: 26130875; PMCID: PMC4462208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polonski L, Gasior M, Gierlotka M, Osadnik T, Kalarus Z, Trusz-Gluza M, et al. ; PL-ACS Registry Pilot Group. A comparison of ST elevation versus non-ST elevation myocardial infarction outcomes in a large registry database: are non-ST myocardial infarctions associated with worse long-term prognoses? Int J Cardiol. 2011. Oct 6;152(1):70–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.07.008. Epub 2010 Aug 3 PMID: 20684999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mokhtari A, Dryver E, Söderholm M, Ekelund U.. Diagnostic values of chest pain history, ECG, troponin and clinical gestalt in patients with chest pain and potential acute coronary syndrome assessed in the emergency department. Springerplus. 2015. May 7;4:219. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-0992-9 PMID: 25992314; PMCID: PMC4431985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, Amsterdam E, Bhatt DL, Birtcher KK, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021. Nov 30;144(22):e368–e454. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029 Epub 2021 Oct 28. Erratum in: Circulation. 2021. Nov 30;144(22): e455. PMID: 34709879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connor RE, Al Ali AS, Brady WJ, Ghaemmaghami CA, Menon V, Welsford M, et al. Part 9: Acute Coronary Syndromes: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015. Nov 3;132(18 Suppl 2):S483–500. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000263 PMID: 26472997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, Alonzo A, Croft JB, Dracup K, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006. Jul 11;114(2):168–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. Epub 2006 Jun 26 PMID: 16801458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepple BI, Thistlethwaite WA, Schumann CL, Akosah KO, Schutt RC, Keeley EC.. Treatment of Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Process Analysis of Patient and Program Factors in a Teaching Hospital. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2016. Sep;15(3):106–11. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000083 PMID: 27465006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diercks DB, Kirk JD, Lindsell CJ, Pollack CV Jr, Hoekstra JW, Gibler WB, et al. Door-to-ECG time in patients with chest pain presenting to the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006. Jan;24(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.016 PMID: 16338501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox JL, Zitner D, Courtney KD, Mac-Donald DL, Paterson G, Cochrane B, et al. Undocumented patient information: an impediment to quality of care. Am J Med. 2003. Feb 15;114(3):211–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01481-x PMID: 12641082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunlay SM, Alexander KP, Melloni C, Kraschnewski JL, Liang L, Gibler WB, et al. Medical records and quality of care in acute coronary syndromes: results from CRUSADE. Arch Intern Med. 2008. Aug 11;168(15):1692–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1692 PMID: 18695085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roe MT, Halabi AR, Mehta RH, Chen AY, Newby LK, Harrington RA, et al. Documented traditional cardiovascular risk factors and mortality in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2007. Apr;153(4):507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.12.018 PMID: 17383286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang U, Graff L, Krumholz HM, Radford MJ.. The association between emergency department over-crowding and time to antibiotic administration [Internet]. Mosby; 2004. [cited 2023 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0196064404007450 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schull MJ, Morrison LJ, Vermeulen M, Redelmeier DA.. Emergency department overcrowding and ambulance transport delays for patients with chest pain. CMAJ. 2003. Feb 4;168(3):277–83. PMID: 12566332; PMCID: PMC140469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schull MJ, Vermeulen M, Slaughter G, Morrison L, Daly P.. Emergency department crowding and thrombolysis delays in acute myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med. 2004. Dec;44(6):577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.004 Erratum in: Ann Emerg Med. 2005. Jan;45(1): 84. PMID: 15573032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emergency department: rapid identification and treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction. National Heart Attack Alert Program Coordinating Committee, 60 Minutes to Treatment Working Group. Ann Emerg Med. 1994. Feb;23(2):311–29. PMID: 8304613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Task Force for Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes of European Society of Cardiology; Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, Boersma E, Budaj A, Fernández-Avilés F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2007. Jul;28(13):1598–660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. Epub 2007 Jun 14 PMID: 17569677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diercks DB, Peacock WF, Hiestand BC, Chen AY, Pollack CV Jr, Kirk JD, et al. Frequency and consequences of recording an electrocardiogram >10 minutes after arrival in an emergency room in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (from the CRUSADE Initiative). Am J Cardiol. 2006. Feb 15;97(4):437–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.073. Epub 2005 Dec 13 PMID: 16461033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. PLATO Investigators; Freij A, Thorsén M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009. Sep 10;361(11):1045–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. Epub 2009 Aug 30 PMID: 19717846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, et al. TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007. Nov 15;357(20):2001–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. Epub 2007 Nov 4 PMID: 17982182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021. Apr 7;42(14):1289–1367. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 May 14;42(19):1908. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 May 14;42(19):1925 Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 May 13;: PMID: 32860058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valina C, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Wöhrle J, Bernlochner I, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. Nov 24;76(21):2436–2446. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.584 PMID: 33213722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lahu S, Presch A, Ndrepepa G, Menichelli M, Valina C, Hemetsberger R, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome and High Bleeding Risk. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022. Oct;15(10):e012204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012204. Epub 2022 Oct 18 PMID: 36256695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ray A, Najmi A, Khandelwal G, Jhaj R, Sadasivam B.. Usefulness of the PRECISE-DAPT score at differentiating between ticagrelor and prasugrel for dual antiplatelet therapy initiation. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2023. Oct;56(3):411–413. doi: 10.1007/s11239-023-02857-z. Epub 2023 Jul 4 PMID: 37402078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar A, Lutsey PL, St Peter WL, Schommer JC, Van't Hof JR, Rajpurohit A, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Ticagrelor, Prasugrel, and Clopidogrel for Secondary Prophylaxis in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023. Feb;113(2):401–411. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2797. Epub 2022 Dec 13 PMID: 36399019; PMCID: PMC9877194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Ascenzo F, Iannaccone M, De Filippo O, Leone AM, Niccoli G, Zilio F, et al. Optical coherence tomography compared with fractional flow reserve guided approach in acute coronary syndromes: A propensity matched analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017. Oct 1;244:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.108. Epub 2017 Jun 3 PMID: 28629622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burzotta F, Leone AM, Aurigemma C, Zambrano A, Zimbardo G, Arioti M, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve or Optical Coherence Tomography to Guide Management of Angiographically Intermediate Coronary Stenosis: A Single-Center Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020. Jan 13;13(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.09.034 PMID: 31918942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clemmensen P, Roe MT, Hochman JS, Cyr DD, Neely ML, McGuire DK, et al. ; TRILOGY ACS Investigators. Long-term outcomes for women versus men with unstable angina/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction managed medically without revascularization: insights from the TaRgeted platelet Inhibition to cLarify the Optimal strateGy to medicallY manage Acute Coronary Syndromes trial. Am Heart J. 2015. Oct;170(4):695–705.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.011. Epub 2015 Jun 20 PMID: 26386793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE, Zingmond D, Liang LJ, Han W, et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013. Jun;61(6):605–611.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.026. Epub 2012 Dec 6 PMID: 23218508; PMCID: PMC3690784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basit H, Malik A, Huecker MR.. Non–STSegment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. 2023 Jul 10. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Jan–. PMID: 30020600. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lehmacher J, Neumann JT, Sörensen NA, Goßling A, Haller PM, Hartikainen TS, et al. Predictive Value of Serial ECGs in Patients with Suspected Myocardial Infarction. J Clin Med. 2020. Jul 20;9(7):2303. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072303 PMID: 32698466; PMCID: PMC7408822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Christenson E, Christenson RH.. The role of cardiac biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of patients presenting with suspected acute coronary syndrome. Ann Lab Med. 2013. Sep;33(5):309–18. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.5.309. Epub 2013 Aug 8 PMID: 24003420; PMCID: PMC3756234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee TH, Juarez G, Cook EF, Weisberg MC, Rouan GW, Brand DA, et al. Ruling out acute myocardial infarction. A prospective multicenter validation of a 12-hour strategy for patients at low risk. N Engl J Med. 1991. May 2;324(18):1239–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105023241803 PMID: 2014037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Selker HP, Griffith JL, D'Agostino RB.. A tool for judging coronary care unit admission appropriateness, valid for both real-time and retrospective use. A time-insensitive predictive instrument (TIPI) for acute cardiac ischemia: a multicenter study. Med Care. 1991. Jul;29(7):610–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199107000-00002 Erratum in: Med Care 1992. Feb;30(2): 188. PMID: 2072767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Storrow AB, Gibler WB.. Chest pain centers: diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2000. May;35(5):449–61. PMID: 10783407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCarthy BD, Beshansky JR, D'Agostino RB, Selker HP.. Missed diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department: results from a multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med. 1993. Mar;22(3):579–82. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81945-6 PMID: 8442548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poorhosseini H, Saadat M, Salarifar M, Mortazavi SH, Geraiely B.. Pre-Hospital Delay and Its Contributing Factors in Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction; a Cross sectional Study. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019. May 29;7(1):e29. PMID: 31432039; PMCID: PMC6637811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beig JR, Tramboo NA, Kumar K, Yaqoob I, Hafeez I, Rather FA, et al. Components and determinants of therapeutic delay in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A tertiary care hospital-based study. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2017. Jan;29(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2016.06.001. Epub 2016 Jun 16 PMID: 28127213; PMCID: PMC5247299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Momeni M, Salari A, Shafighnia S, Ghanbari A, Mirbolouk F.. Factors influencing prehospital delay among patients with acute myocardial infarction in Iran. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012. Oct;125(19):3404–9. PMID: 23044296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malhotra S, Gupta M, Chandra KK, Grover A, Pandhi P.. Prehospital delay in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction in the emergency unit of a North Indian tertiary care hospital. Indian Heart J. 2003. Jul-Aug;55(4):349–53. PMID: 14686664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, Woolard RH, Feldman JA, Beshansky JR, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000. Apr 20;342(16):1163–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421603 PMID: 10770981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bassan R, Gibler WB.. Unidades de dolor torácico: estado actual del manejo de pacientes con dolor torácico en los servicios de urgencias [Chest pain units: state of the art of the management of patients with chest pain in the emergency department]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2001. Sep;54(9):1103–9. Spanish. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(01)76457-3 PMID: 11762291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]