Abstract

Background.

A guideline panel convened by the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, and Center for Integrative Global Oral Health at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses and formulated evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain after 1 or more simple and surgical tooth extractions and the temporary management of toothache (that is, when definitive dental treatment not immediately available) associated with pulp and furcation or periapical diseases in children (< 12 years).

Types of Studies Reviewed.

The authors conducted a systematic review to determine the effect of analgesics and corticosteroids in managing acute dental pain. They used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to assess the certainty of the evidence and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Evidence to Decision framework to formulate recommendations.

Results.

The panel formulated 7 recommendations and 5 good practice statements across conditions. There is a small beneficial net balance favoring the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone or in combination with acetaminophen compared with not providing analgesic therapy. There is no available evidence regarding the effect of corticosteroids on acute pain after surgical tooth extractions in children.

Conclusions and Practical Implications.

Nonopioid medications, specifically nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen alone or in combination with acetaminophen, are recommended for managing acute dental pain after 1 or more tooth extractions (that is, simple and surgical) and the temporary management of toothache in children (conditional recommendation, very low certainty). According to the US Food and Drug Administration, the use of codeine and tramadol in children for managing acute pain is contraindicated.

Keywords: Clinical practice guideline, pediatric dentistry, acute dental pain, tooth extractions, toothache, analgesics, opioids, corticosteroids

Children experience toothache, which may be somatic (that is, periodontal, alveolar, or mucosal) or visceral (that is, pulpal),1 and when they have teeth extracted, they may experience pain. The lifetime prevalence of toothache in children aged 0 through 5 years was estimated to be 28%.2 Among children aged 6 through 9 years, the pooled lifetime prevalence of toothache is 52%.2

With respect to pain after dental extraction, in a study of 143 children aged 1 through 16 years who had an urgent dental extraction at a tertiary care teaching hospital, moderate (4-6) through severe (7-10) pain on a scale ranging from 1 through 10, in which 1 through 3 were mild pain, 4 through 6 were moderate pain, and 7 through 10 were severe pain, was experienced by 9.8% of the children postoperatively on the day of surgery, by 4.2% on postoperative day 1, and by 2.1% on postoperative day 2.3 Moderate through severe pain occurred more often among children who had more than 1 tooth extracted. The approach to pain management was different when the children were in the hospital compared with when they returned home. For example, over the course of their time in the hospital before discharge, 90% of the children took an opioid, 50% took acetaminophen, and 18% took a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).3 At home, on postoperative day 1, 22% of the children took acetaminophen, 12% took an NSAID, and 5% took a combination of acetaminophen and codeine.

Private insurance claims data from 2010 through 2015 in the United States indicate that among children younger than 11 years with a dental visit and an opioid prescription, the median days’ supply of the opioid was 3 days and the median daily dose was 10.80 morphine mg equivalents.4 Most of these prescriptions were associated with surgical dental visits (69.51%), and the remainder (30.42%) were associated with nonsurgical dental visits. In addition, among children younger than 11 years with more than 1 opioid prescription in a year, 6.75% of the initial prescriptions were associated with a dental visit.5

Although children experience adverse effects when their pain is not managed, they also can experience adverse effects from the medication used to manage their pain, depending on the medication. When acetaminophen or NSAIDs are administered as directed, the risk of harm to children from either medication is low. However, the risk of harm from opioids is of concern.6 In a study of children without severe conditions enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid, the incidence of opioid-related serious adverse effects (emergency department visit, hospital admission, death related to an opioid-related adverse effect) for children aged 2 through 5 years was 1.4 of 100,000 days, and for children aged 6 through 11 years, it was 1.3 of 100,000 days.7 In addition, in children aged 2 through 5 years, opioid-related serious adverse effects were associated with the therapeutic use of the medication 80% of the time, and in children aged 6 through 11 years, the rate was 94% of the time.7 Thus, when children use opioid-containing medications to manage pain, they can experience serious adverse effects, such as hospital admission or death, even when opioids were prescribed at therapeutic doses.

One approach to reducing oral health care providers’ prescription of opioids is through the use of clinical practice guidelines. In 2012, the World Health Organization published a pediatric pain management guideline8 in which a 2-step, multimodal approach was recommended. For mild pain, the guideline recommended caregivers provide a combination of an NSAID (ibuprofen) and acetaminophen. For moderate through severe pain, the guideline recommended caregivers add an opioid to the ibuprofen and acetaminophen combination. In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a safety communication addressing pain in children younger than 12 years restricting the use of codeine and tramadol, which resulted in a labeling change.9 In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentists published a guideline in which acetaminophen and NSAIDs were recommended as the first-line pharmacologic approach to pain management and the use of opioids was recommended to be rare.1

Although oral health care providers have been decreasing the prescription of opioid-containing medications to children, they continue to prescribe opioids. In a study of opioid prescriptions dispensed to children in 2019, 1.1 of 100 children aged 0 through 11 years received an opioid prescription,10 of which 8.4% were for codeine and 7.7% were for tramadol. As described above, the FDA in 2017 restricted the use of codeine and tramadol for children.9 For children aged 0 through 11 years, dentists accounted for 11.8% of the prescriptions. Thus, contraindicated and guideline-discordant prescribing continued.

The purpose of this evidence-based guideline is to provide recommendations to assist clinicians, patients, and guardians in the case of pediatric patients in determining the most appropriate use of pharmacologic strategies for the management of acute dental pain after simple and surgical tooth extractions and the temporary management of toothache associated with pulp and furcation or periapical disease in children.

METHODS

In developing this guideline, we followed the methodological advice of the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) workgroup, which is the first time these methodologies have been used to produce a guideline to inform this population and these clinical scenarios.11,12

Guideline scope

This guideline focuses on formulating recommendations for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain in children (< 12 years) associated with 1 or more simple or surgical (that is, extraction of a tooth with the need of a flap, osteotomy) tooth extractions or toothache (symptomatic pulpitis [that is, reversible or symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis or symptomatic furcation or periapical involvement] or pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis or periapical or furcation pathosis, or acute apical abscess) with no immediate access to definitive dental treatment (for example, a referral from emergency department to a dental practice or referral from a general dentist to a dental specialist).

Target audience

These recommendations are intended primarily for general dentists. Dentists in specialty practice, dental educators, emergency and primary care physicians, medical and dental students, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, dental therapists, dental hygienists, and policy makers may also benefit from these recommendations.

Guideline development group

We created 2 collaborative groups. The first group, the guideline panel, comprised 14 members, including dental and medical care practitioners, clinical researchers, epidemiologists, pharmacologists with particular expertise in pain management, public health dentists, and a patient partner. The second group, the methodological team, included researchers from the American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, McMaster University, Center for Integrative Global Oral Health at the University of Pennsylvania, and Art of Democracy, with extensive expertise in systematic review methodology, guideline development, stakeholder engagement, implementation and behavioral sciences, and biostatistics. All meetings to define the guideline scope, target audience, and clinical questions and formulate recommendations occurred remotely from December 2020 through December 2021 (Appendix, available online at the end of this article).

Guideline development

Clinical Questions Addressed in This Guideline

The panel defined the scope, purpose, target audience, and clinical questions addressed in this guideline and prioritized 2 areas to formulate recommendations: acute dental pain in children associated with tooth extractions (surgical, simple) and toothache (symptomatic pulpitis [that is, reversible or symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis or symptomatic furcation or periapical involvement] or pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis or furcation or periapical disease, or acute apical abscess) with no immediate access to definitive dental treatment. Definitive dental treatment included pulpectomy, nonsurgical root canal treatment, incision and drainage of abscess, and tooth extraction. The panel selected opioid and nonopioid analgesic medications (for example, NSAIDs and acetaminophen) administered orally regardless of the vehicle or as a suppository and corticosteroids administered at any dose or frequency orally (eTable, available online at the end of this article). Analgesics and corticosteroids administered intravenously are out of the scope of this guideline. The panel also identified patient-important outcomes for each set of interventions, including pain relief, pain intensity, global subjective efficacy rating, rescue analgesia, and any reported adverse effects (for example, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, dysphagia, diarrhea, constipation, dyspepsia, dizziness, drowsiness, syncope, mood alteration, and headache). We collected information on the sum of pain relief scores at each observational time point (for example, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours … 6 hours), which is the total pain relief, and the summed pain intensity difference expressed as the sum of pain intensity differences between each observational time point (for example, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours … 6 hours) and baseline.6 Once the panel defined patients’ features, clinical conditions, interventions under comparison, and outcomes of interest, we implemented a first electronic survey via Qualtrics to gather feedback from identified stakeholder organizations (eBox, available online at the end of this article). We asked stakeholders to evaluate the completeness and relevance of each clinical question addressed in the guideline. This input was analyzed and discussed in a virtual guideline panel meeting to decide the necessary amendments to incorporate stakeholders’ input before conducting the systematic reviews and guideline work.

Systematic Reviews and Literature Searches Informing the Guideline

The methodological team conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses to address the clinical questions regarding the benefits and harms of the included interventions. A complete report of the systematic review informing this guideline is available elsewhere.6 Briefly, we searched MEDLINE via PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Epistemonikos database, and the gray literature from database inception through September 2021 and conducted study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment (using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool for randomized controlled trials [RCTs]13) independently and in duplicate. We created GRADE summary-of-findings tables to display the effect of the interventions in relative and absolute estimates, number of studies and participants, and certainty of the evidence per outcome.

Values and Preferences

We conducted a targeted search for primary studies or systematic reviews reporting on patients’, parents’, guardians’, or caregivers’ values and preferences, defined as the extent to which any of the aforementioned value the main outcomes and define their relative importance when managing acute dental pain.

Development of Recommendations

In a consensus-building process informed by evidence, the panel was presented with the best available evidence from the systematic review addressing the predefined clinical questions. To guide the process, we used the GRADE Evidence to Decision framework (Appendix, available online at the end of this article),14 allowing the panel to provide 3 types of guidance15: (1) graded recommendation statements directly informed by the systematic review and meta-analysis, along with the overall certainty of the evidence and strength of recommendation (Table 112,16,17); (2) good practice statements supported by substantial indirect evidence; and (3) the guideline panel’s remarks including nonsystematically collected evidence, extensive clinical and research experience, and official documents from regulatory agencies and stakeholder organizations. In the rare instances when the consensus building process failed to provide clear guidance, the panel proceeded to vote, with a simple majority defining the selected course of action.

Table 1.

Definitions of certainty in the evidence and strength of recommendations and implications for patients, clinicians, and policy makers.*

| CATEGORY | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Definitions of Certainty (Quality) of the Evidence | |

| High | Very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

| Low | Confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very low | Very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. |

| Definitions of Strong and Conditional Recommendations and Implications for Users | |

| Implications for patients | |

| Strong recommendations | Most patients in this situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help patients make decisions consistent with their values and preferences |

| Conditional recommendations | Most patients in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not |

| Implications for clinicians | |

| Strong recommendations | Most patients should receive the intervention. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator |

| Conditional recommendations | Recognize that different choices will be appropriate for individual patients and that the clinician must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with his or her values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients make decisions consistent with their values and preferences |

| Implications for policy makers | |

| Strong recommendations | The recommendation can be adapted as policy in most situations |

| Conditional recommendations | Policy making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders |

External Review and Updating Process

After producing the first draft of the recommendations and good practice statements, we implemented a second electronic survey via Qualtrics to consult with and receive input from the same group of stakeholder organizations initially contacted (eBox, available online at the end of this article). The survey included the newly formulated statements, their certainty of the evidence and strength of recommendations, and a series of questions addressing the statements’ appropriateness, clarity, and relevance. In addition, we conducted a similar process to receive input through a public comment consultation via a website and implemented using an electronic survey. The panel analyzed this input and determined the necessary actions to address stakeholders’ and public concerns and produced the final version of the recommendations and good practice statements (eBox, available online at the end of this article).

RESULTS

Recommendations

How to Use These Recommendations

These evidence-based recommendations and good practice statements should not replace clinical judgment nor cover all potential clinical scenarios when managing acute dental pain in children. Rather, they serve as assistance for patients, parents, guardians, caregivers, clinicians, administrators, and policy makers when making management decisions. Practitioners should remain alert to patient-specific nuance and unusual situations that may warrant a deviation from these recommendations.

Values and Preferences

The panel did not identify direct evidence addressing children’s or caregivers’ values and preferences when managing acute dental pain. Indirect evidence for acute pain related to surgical non–dental-related procedures in children (for example, tonsillectomy and urologic or orthopedic surgery) suggests that parents or guardians may have a relatively high threshold for preferring an opioid (threshold in the Faces pain scale of 7.5 of 10), meaning that they may place a higher value on avoiding undesirable or harmful outcomes when children experience moderate or mild pain.18 It is the panel’s opinion that there may be some variability in the perceived pain threshold at which parents or guardians would decide that an opioid (or intervention with high risk of adverse effects) is acceptable.

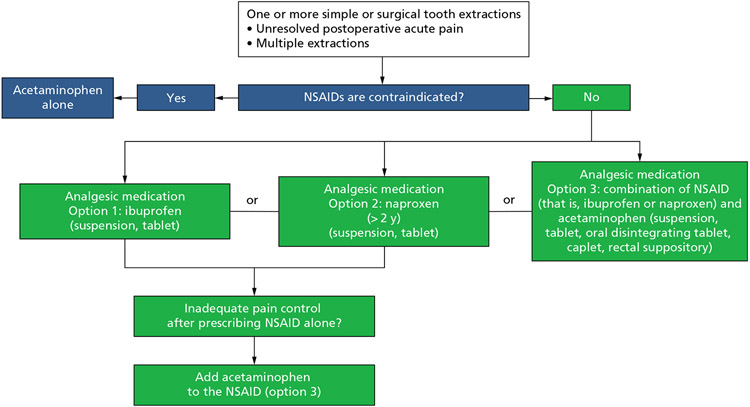

Recommendations for the pharmacologic management of postoperative pain after 1 or more surgical or simple tooth extractions in children (Box 1 and Figure 1)

Box 1. Key recommendations and good practice statements for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain: postoperative pain after 1 or more simple or surgical tooth extractions in children.

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|

| 1. For the management of acute postoperative dental pain in children* undergoing 1 or more simple or surgical tooth extractions,† the guideline panel suggests initiating the pain management scheme using ibuprofen (suspension, tablet) alone,‡ naproxen (> 2 years)§ (suspension, tablet) alone,‡ or either of the 2 in combination with acetaminophen‡ (suspension, tablet, oral disintegrating tablet, caplet, rectal suppository) over the use of acetaminophen alone (conditional, very low certainty). |

| 1.1. If postprocedural (that is, simple or surgical tooth extraction†) pain control using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone is inadequate, the guideline panel suggests the addition of acetaminophen‡ (conditional, very low certainty). |

| 1.2. When nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated,¶ the guideline panel suggests the use of acetaminophen alone (conditional, very low certainty). |

| 2. For the management of acute postoperative dental pain in children* undergoing 1 or more surgical tooth extractions,† the panel will not formulate recommendations for or against corticosteroids owing to a paucity of evidence. |

| GOOD PRACTICE STATEMENTS |

| ● The guideline panel advises clinicians to assess children’s pain using suitable tools for their ages. For example, a Faces scale (≥ 3 years), a numerical rating scale (≥ 8 years), a visual analog scale (≥ 8 years), or a behavioral scale (1-3 years). |

| ● The guideline panel advises clinicians to counsel patients and their caregivers that they should expect some pain and the analgesics should make their pain manageable. The guideline panel also recommends discussing with the patient, parent, guardian, or caregiver their past experiences, preferences, and values regarding managing acute dental pain before prescribing. |

| ● The guideline panel recommends clinicians thoroughly review the patient’s medical and social histories and medications and supplements to avoid overdose and adverse drug-drug interactions. |

| ● According to the FDA, codeine and tramadol are contraindicated¶ in children younger than 12 years. |

The guideline panel defined children as patients younger than 12 years.

Not all extractions in children will require the use of an analgesic. This recommendation applies only when there is unresolved postoperative pain or when conducting multiple extractions.

When defining dosages, weight should be the primary directive as opposed to age.

The recommendation for the use of naproxen in children older than 2 years in this guideline is an off-label use. Naproxen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as young as 12 years. Naproxen is also approved for prescription use only in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis as young as age 2 years. Naproxen is not approved by the FDA in children aged 0 through 2 years.

“A drug should be contraindicated only in those clinical situations for which the risk from use clearly outweighs any possible therapeutic benefit. Only known hazards, and not theoretical possibilities, can be the basis for a contraindication.“19

Figure 1.

Clinical pathway for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain: postoperative pain after surgical and simple tooth extractions in children. Naproxen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for prescription use only in pediatric patients older than 2 years with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The recommendation for the use of naproxen in children older than 2 years in this guideline is an off-label use. NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Summary of Main Findings

Analgesics medications for surgical and simple tooth extractions

Overall, moderate through very low certainty evidence from 4 RCTs across outcomes of benefits and harms suggests that ibuprofen alone could decrease the need for rescue analgesia and may reduce pain intensity by a negligible amount after 4 hours compared with not using ibuprofen (placebo). Moderate through very low certainty evidence from 5 RCTs suggest that acetaminophen alone may reduce pain intensity by a negligible amount after 4 hours compared with not using acetaminophen (placebo). Moderate through very low certainty evidence from 5 RCTs suggests that ibuprofen alone could reduce pain intensity by a negligible amount and may reduce the need for rescue analgesia by an important amount at 4 hours compared with acetaminophen alone. Moderate certainty evidence from 1 RCT indicates that the combination of acetaminophen plus ibuprofen likely reduces pain by an important amount compared with the use of acetaminophen or ibuprofen alone. Low to very low certainty evidence from a single trial suggests that acetaminophen with codeine may produce a trivial reduction in pain intensity and a trivial increase in pain relief compared with placebo, acetaminophen alone, or ibuprofen alone.

Our systematic review did not identify direct evidence (no studies) informing the effects of naproxen-containing medications for managing acute dental pain in children. However, indirect evidence from RCTs in adolescents and adults suggests that ibuprofen and naproxen sodium are among the most effective analgesics for managing acute dental pain.20 The panel determined that although the evidence is indirect to acute dental pain in children, there are no clinical reasons to suspect that naproxen would be less effective compared with its use in adolescents and adults. Regarding naproxen’s safety profile, this NSAID is FDA approved for prescription use in pediatric patients older than 2 years with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (5-6 mg/kg every 12 hours as needed in children < 60 kg, or ≈ 132 pounds).

Oral, submucosal, or intramuscular corticosteroids for surgical tooth extractions

Our systematic review did not identify any study evaluating the desirable and undesirable effects of corticosteroids administered orally at any dose or frequency in children undergoing tooth extraction.

Remarks

Not all tooth extractions in children would require the implementation of an analgesic strategy. These recommendations apply when there is unresolved postoperative pain, when conducting multiple extractions in a single session, or when conducting surgical tooth extractions that may require osteotomy soft-tissue manipulation.

The recommendation statements are based on dosing for professionally prescribed analgesics and do not address over-the-counter indications and dosages. The recommendation for the use of naproxen in children older than 2 years in this guideline is an off-label use. Naproxen is FDA approved for use in children as young as 12 years. Naproxen is also approved for prescription use only in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis as young as 2 years. Naproxen is not FDA approved in children aged from 0 through 2 years.21

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry states: “While the prolonged effect of a long-acting local anesthetic (ie, bupivacaine) can be beneficial for post-operative pain in adults, the concomitant increased risk of self-inflicted injury [eg, lip biting] infers that it is contraindicated for the child or the physically or intellectually disabled patient.”1

The FDA stated in 2017 that is adding the following to labels of prescription medicines containing codeine and tramadol: “FDA’s strongest warning, called a Contraindication, to the drug labels of codeine and tramadol alerting that codeine should not be used to treat pain or cough and tramadol should not be used to treat pain in children younger than 12 years.”9

Parents, guardians, and caregivers should be advised to carefully follow instructions on the medication label or prescription for appropriate dosage. To minimize adverse effects, analgesic prescriptions should follow the principle of minimum effective dosage to achieve pain relief (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medication dosages for the management of acute dental pain in children.

| AGE | WEIGHT | DOSAGE, MG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kg | lb | ||

| Ibuprofen (Suspension, Tablet) * | |||

| 6-11 mo | 5.4-8.1 | 12-17 | 50 |

| 12-23 mo | 8.2-10.8 | 18-23 | 75 |

| 2-3 y | 10.9-16.3 | 24-35 | 100 |

| 4-5 y | 16.4-21.7 | 36-47 | 150 |

| 6-8 y | 21.8-27.2 | 48-59 | 200 |

| 9-10 y | 27.3-32.6 | 60-71 | 250 |

| 11 y | 32.7-43.2 | 72-95 | 300 |

| Acetaminophen (Suspension, Tablet, Oral Disintegrating Tablet, Caplet, Rectal Suppository) † | |||

| 0-3 mo | 2.7-5.3 | 6-11 | 40 |

| 4-11 mo | 5.4-8.1 | 12-17 | 80 |

| 1-2 y | 8.2-10.8 | 18-23 | 120 |

| 2-3 y | 10.9-16.3 | 24-35 | 160 |

| 4-5 y | 16.4-21.7 | 36-47 | 240 |

| 6-8 y | 21.8-27.2 | 48-59 | 320 |

| 9-10 y | 27.3-32.6 | 60-71 | 400 |

| 11 y | 32.7-43.2 | 72-95 | 480 |

| Naproxen (Suspension, Tablet) ‡ | |||

| > 2 y | < 60 | < 132 | 5-6 per kg every 12 h as needed; maximum daily dose of 1,000 for naproxen and 1,100 for naproxen sodium |

| > 2 y | ≥ 60 | ≥ 132 | 250-375 every 12 h as needed; maximum daily dose of 1,000 for naproxen and 1,100 for naproxen sodium |

Dosing based on child’s weight and age. Usual oral dosage: infants and children ≤ 11 y and < 50 kg, 4-10 mg/kg per dose every 6-8 h as needed (maximum single dose, 400 mg; maximum dose, 40 mg/kg per 24 h).

Dosing based on child’s weight and age. Usual oral dosage: infants and children ≤ 11 y, 10-15 mg/kg per dose every 4-6 h as needed (maximum 75 mg/kg per 24 h but not to exceed 4,000 mg per 24 h). Both short- and long-term doses of acetaminophen are associated with hepatotoxicity. For this reason, this drug has been reformulated, so the products are limited to 325 mg per dosage unit.

Dosage expressed as 200 mg naproxen base is equivalent to 220 mg naproxen sodium. For acute pain, naproxen sodium may be preferred because of increased solubility leading to faster onset, higher peak concentration, and decreased adverse drug events.

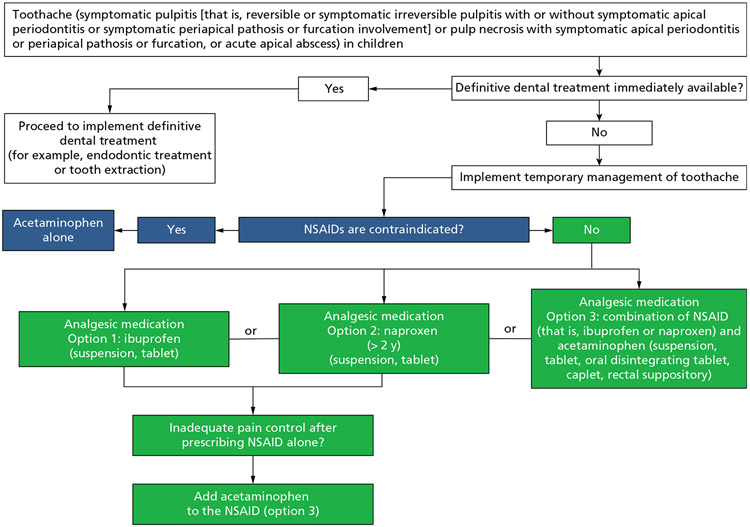

Recommendations for the temporary pharmacologic management of toothache (symptomatic pulpitis [that is, reversible or symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis or symptomatic furcation or periapical involvement] or pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis or furcation or periapical disease, or acute apical abscess) with no immediate access to definitive dental treatment in children (Box 2 and Figure 2)

Box 2. Recommendations and good practice statements for the temporary pharmacologic management of toothache in children with no immediate access to definitive dental treatment.

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|

| 1. For the temporary management* of toothache (symptomatic pulpitis [that is, reversible or symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with or without symptomatic apical periodontitis or symptomatic periapical or furcation involvement] or pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis or periapical or furcation pathosis, or acute apical abscess) before definitive dental treatment in children,† the guideline panel suggests the use of ibuprofen (suspension, tablet) alone,‡ naproxen (> 2 years)§ (suspension, tablet) alone,‡ or either of the 2 in combination with acetaminophen‡ (suspension, tablet, oral disintegrating tablet, caplet, rectal suppository) over the use of acetaminophen alone (conditional, very low certainty). |

| 1.1. If pain control using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone is inadequate, the guideline panel suggests the addition of acetaminophen‡ (conditional, very low certainty). |

| 1.2. When nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated,¶ the guideline panel suggests the use of acetaminophen alone (conditional, very low certainty). |

| GOOD PRACTICE STATEMENTS |

| ● The guideline panel advises clinicians to assess children’s pain using suitable tools for their ages. For example, a Faces scale (≥ 3 years), a numerical rating scale (≥ 8 years), a visual analog scale (≥ 8 years), or a behavioral scale (aged 1-3 years). |

| ● The guideline panel advises clinicians to counsel patients and their caregivers that they should expect some pain and the analgesics should make their pain manageable. The guideline panel also recommends discussing with the patient, parent, guardian, or caregiver their past experiences, preferences, and values regarding managing acute dental pain before prescribing. |

| ● The guideline panel reminds users of these recommendations that they only apply to settings in which definitive dental treatment is not immediately available. These pharmacologic strategies will alleviate dental pain temporarily until a referral for definitive dental treatment is in place. |

| ● The guideline panel recommends clinicians thoroughly review the patient medical and social history and medications and supplements to avoid overdose and adverse drug-drug interactions. |

| ● According to the US Food and Drug Administration, codeine and tramadol are contraindicated¶ in children younger than 12 years. In addition, topical benzocaine should not be used in infants or young children owing to the high risk of methemoglobinemia. |

These recommendations are applicable only to settings in which definitive dental treatment is not available. Definitive dental treatment includes pulpectomy, nonsurgical root canal treatment, incision for drainage of abscess, and tooth extraction. Patients or their caregivers should be instructed to call if their pain fails to lessen over time or to call if the referral to receive definitive dental treatment within 2 through 3 days is not possible.

The guideline panel defined children as patients younger than 12 years.

When defining dosages, weight should be the primary directive as opposed to age.

The recommendation for the use of naproxen in children older than 2 years in this guideline is an off-label use. Naproxen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as young as age 12 years. Naproxen is also approved for prescription use only in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis as young as age 2 years. Naproxen is not FDA approved in children aged 0 through 2 years.

“A drug should be contraindicated only in those clinical situations for which the risk from use clearly outweighs any possible therapeutic benefit. Only known hazards, and not theoretical possibilities, can be the basis for a contraindication.”19

Figure 2.

Clinical pathway for the temporary pharmacologic management of toothache with no immediate access to definitive dental treatment in children. Naproxen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for prescription use only in pediatric patients older than 2 years with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The recommendation for the use of naproxen in children older than 2 years in this guideline is an off-label use. NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Summary of Main Findings

Analgesic medications for toothache

The systematic review did not identify evidence regarding the effect of analgesics on the temporary management of symptomatic pulpitis or furcation or periapical disease. Thus, the panel informed these recommendations using indirect evidence from the RCTs evaluating the effect of analgesics on postoperative pain after tooth extractions.

Remarks

The panel reminds users of these recommendations that they only apply to settings in which definitive dental treatment is not immediately available. The use of any analgesic strategy is temporary and does not represent definitive dental care (for example, tooth extraction, pulp therapy, and endodontic treatment).

The recommendations are based on dosing for professionally prescribed analgesics and do not address over-the-counter indications and dosages. The recommendation for the use of naproxen in children older than 2 years in this guideline is an off-label use. Naproxen is FDA approved for use as young as 12 years. Naproxen is approved for prescription use only in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis as young as 2 years. Naproxen is not FDA approved in children aged 0 through 2 years.21

These recommendations also serve as a bridge between the first consultation for toothache and a second referral consultation to receive definitive dental treatment.

Although not included in the scope of this guideline, the guideline panel reminds clinicians that the FDA states, “Benzocaine can cause a serious condition in which the amount of oxygen carried through the blood is greatly reduced. This condition, called methemoglobinemia, is life-threatening and can result in death. Therefore, the FDA is warning that [over-the-counter] oral drug products containing benzocaine should not be used to treat infants and children younger than 2 years. [The panel is also warning] that benzocaine oral drug products should only be used in adults and children 2 years and older if they contain certain warnings on the drug facts label. These products carry serious risks and provide little to no benefit for the treatment of oral pain including teething.”22

Parents, guardians, and caregivers should be advised to carefully follow instructions on the medication label or prescription for appropriate dosage. To minimize adverse effects, analgesic prescriptions should follow the principle of minimum effective dosage to achieve pain relief (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Implications for practice and policy

NSAIDs, in particular ibuprofen and naproxen sodium alone or in combination with acetaminophen, are the preferred therapy for the management of acute dental pain after tooth extractions and for toothache in children. In addition, acetaminophen alone is recommended only when NSAIDs are contraindicated. However, not all clinical situations require the use of analgesics in children. Most children with toothache and extraction receiving definitive dental care for these conditions can successfully have their pain managed with nonpharmacologic therapy (for example, ice) if analgesia is needed. Avoiding the provision of opioids to children is also valued by parents or guardians. Indirect evidence suggests that parents and caregivers place a high value on avoiding undesirable consequences of using opioids in children. A paucity of evidence regarding the benefits and harms of the use of corticosteroids for the management of postoperative pain after tooth extraction prevented the panel from formulating a recommendation for or against this intervention. The panel highlights to clinicians the importance of counseling patients and their caregivers that they should expect some pain after a tooth extraction or when managing toothache temporarily and that the analgesics should make the pain manageable. The panel urges policy makers to advocate for increasing access to oral health care to minimize the use of analgesics in children having symptomatic pulpitis and furcation or periapical disease and rather facilitate the provision of definitive dental treatment.

Implications for research

Only 7 studies informed the body of evidence for this guideline. We identified a number of limitations that warranted rating down the certainty of the evidence. First, serious issues of risk of bias were present across all included studies, including lack of implementation of allocation concealment, issues of missing participant data, and selective outcome reporting. For example, most studies reported that participants experienced some adverse events like nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and drowsiness; however, the studies also failed to provide per-arm event rates and measures of variability for continuous outcomes, preventing the calculation of effect measures. Second, serious issues of imprecision due to the small number of participants per study (median, 85 participants) affected all outcomes informing this guideline. An additional gap is the lack of studies elucidating children’s parents’, guardians’, and caregivers’ values and preferences when managing acute dental pain. We invite researchers and grant agencies to increase the volume and quality of RCTs informing the effectiveness and safety of analgesic strategies when managing pain after tooth extractions and toothache, including detailed documentation and reporting of adverse effects. For example, the panel did not identify any study informing the effect of naproxen in children with acute dental pain. In addition, more attention to the assessment of children’s parents’, guardians’, and caregivers’ values and preferences is warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

Nonopioid medications, specifically NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen alone or in combination with acetaminophen, are recommended for managing acute dental pain after 1 or more tooth extractions (that is, simple and surgical) and the temporary management of toothache in children. According to the FDA, the use of codeine and tramadol in children for managing acute pain is contraindicated.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures.

Dr. Aghaloo is the associate editor, Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Dr. Dionne has received compensation in the form of honoraria or travel funds for serving as a speaker or consultant for management of acute dental pain. Dr. Gordon has received research funding related to acute dental pain; funds were paid to the affiliated universities in the form of grants and contracts. Dr. Hersh, on behalf of the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, has received funding from Charleston Laboratories, Pfizer Consumer Healthcare, Cetylite, Bayer Healthcare, Penn Medicine Center of Precision Medicine, and the National Institutes of Health and consulting fees from Johnson & Johnson and Bayer Healthcare. Dr. Schwartz is president, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, and president, American Dental Society of Anesthesiology. None of the other authors reported any disclosures.

The guideline development team acknowledge the significant technical and methodological support provided by the US Food and Drug Administration team, particularly Dr. Frederick Hyman and Dr. Menglu Yuan, and Dr. Natalia Chalmers, formerly of the US Food and Drug Administration.

The guideline development team thanks the American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Scientific Affairs Clinical Excellence Subcommittee for its extensive efforts in convening a multidisciplinary panel to conduct this guideline; Laura Pontillo, coordinator, ADA Library & Archives, for assistance in retrieving full-text articles for the systematic reviews; Jeff Huber, former scientific communication manager, ADA Science and Research Institute, for his support in the implementation and retrieval of comments from the public and for leading the guideline dissemination strategies and tactics; Archana Ramesh for assisting in the classification and processing of stakeholder organizations’ comments on the scope, purpose, target audience, and clinical questions; Richard Morley, consumer engagement officer, Cochrane, for his guidance and continuous support in helping locate a patient partner member for the guideline panel; the stakeholder organizations, the public, and other entities that provided feedback to the recommendation statements, the certainty of the evidence, and strength of recommendations. Their thoughtful and thorough input directly informed the final wording and extension of the graded recommendations, good practice statements, and remarks.

This project was financially supported by grant U01FD007151 from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), US Department of Health and Human Services. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of nor an endorsement by the FDA and Department of Health and Human Servicves or the US Government. The funders had no decision-making role in designing and conducting the systematic reviews, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or approval privilege on the recommendation and good practice statements. As requested, FDA officers provided nonbinding feedback and technical support to the guideline panel and methodological team. This article was peer reviewed before publication. These guidelines are intended to help inform clinical decision making by prescribers and patients. They are not intended to be used for the purposes of restricting, limiting, delaying, or denying coverage for or access to a prescription issued for a legitimate medical purpose by an individual practitioner acting in the usual course of professional practice.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ABBREVIATION KEY

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- NSAID

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data related to this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2023.06.014.

Contributor Information

Alonso Carrasco-Labra, Department of Evidence Synthesis and Translation Research, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute; Center for Integrative Global Oral Health, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA..

Deborah E. Polk, School of Dental Medicine and the Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA..

Olivia Urquhart, Department of Evidence Synthesis and Translation Research, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL; Center for Integrative Global Oral Health, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA..

Tara Aghaloo, School of Dentistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; Council on Scientific Affairs, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL..

J. William Claytor, North Carolina Caring Dental Professionals, Shelby, NC..

Vineet Dhar, University of Maryland School of Dentistry, Baltimore, MD..

Raymond A. Dionne, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT; Council on Scientific Affairs, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL..

Lorena Espinoza, Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA..

Sharon M. Gordon, College of Dental Medicine, Kansas City University, Kansas City, MO..

Elliot V. Hersh, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Alan S. Law, Division of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; The Dental Specialists, Woodbury, MN..

Brian S.-K. Li, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ; Penn Medicine Center for Evidence-based Practice, Philadelphia, PA..

Paul J. Schwartz, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA..

Katie J. Suda, Division of General Internal Medicine, Schools of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PA..

Michael A. Turturro, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA..

Marjorie L. Wright, A.T. Still University College of Graduate Health Studies, Kirksville, MO..

Tim Dawson, The Art of Democracy, Pittsburgh, PA..

Anna Miroshnychenko, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada..

Sarah Pahlke, Clinical and Translational Research, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL; Infectious Diseases Society of America, Arlington, VA..

Lauren Pilcher, Clinical and Translational Research, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL; Quality Initiatives, American Academy of Pediatrics, Itasca, IL..

Michelle Shirey, Department of Dental Public Health, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA..

Malavika Tampi, Department of Cariology, Restorative Sciences, and Endodontics, University of Michigan School of Dentistry, Ann Arbor, MI; Clinical Practice Guidelines, Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago, IL..

Paul A. Moore, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA..

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pain management in infants, children, adolescents, and individuals with special health care needs. In: The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2021:377–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos PS, Barasuol JC, Moccelini BS, et al. Prevalence of toothache and associated factors in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(2):1105–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akl N, Sommerfield A, Slevin L, et al. Anaesthesia, pain and recovery profiles in children following dental extractions. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2020;48(4):306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta N, Vujicic M, Blatz A. Opioid prescribing practices from 2010 through 2015 among dentists in the United States: what do claims data tell us? JADA. 2018; 149(4):237–245,e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta N, Vujicic M, Blatz A. Multiple opioid prescriptions among privately insured dental patients in the United States: evidence from claims data. JADA. 2018;149(7):619–627, e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miroshnychenko A, Azab M, Ibrahim S, et al. Analgesics for the management of acute dental pain in the pediatric population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JADA. 2023;154(5):403–416.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Outpatient opioid prescriptions for children and opioid-related adverse events. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20172156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on the Pharmacological Treatment of Persisting Pain in Children with Medical Illnesses. World Health Organization; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA drug safety communication: FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines and tramadol pain medicines in children; recommends against use in breastfeeding women. US Food and Drug Administration. April 20, 2017. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm549679.htm [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Conti RM, Bohnert AS. Opioid prescribing to US children and young adults in 2019. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021051539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Framing Opioid Prescribing Guidelines for Acute Pain: Developing the Evidence. The National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021). John Willey & Sons; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices, 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotfi T, Hajizadeh A, Moja L, et al. A taxonomy and framework for identifying and developing actionable statements in guidelines suggests avoiding informal recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;141:161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines, 14: going from evidence to recommendations—the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines, 15: going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voepel-Lewis T, Zikmund-Fisher B, Smith EL, Zyzanski S, Tait AR. Opioid-related adverse drug events: do parents recognize the signals? Clin J Pain. 2015;31(3):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidance for industry: warnings and precautions, contraindications, and boxed warning sections of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format. US Food and Drug Administration. October 2011. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/71866/download [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miroshnychenko A, Ibrahim S, Azab M, et al. Acute postoperative pain due to dental extraction in the adult population: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2023;102(4):391–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brutzkus JC, Shahrokhi M, Varacallo M. StatPearls [Internet]: Naproxen. Treasure StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safety information on benzocaine-containing products. US Food and Drug Administration. June 25, 2018. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/safety-information-benzocaine-containing-products [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.