Abstract

Experiencing childhood trauma (CT) can create barriers for developing relationships and is a risk factor for anxiety and depression. Expressive suppression (ES; i.e., reducing expression associated with experiencing emotions) might explain the link between CT and relationship formation difficulties. We examined the association between (1) CT and ES during a dyadic paradigm intended to facilitate connectedness between unacquainted partners and (2) ES and desire for future interaction (DFI). Individuals with an anxiety or depressive disorder diagnosis (N=77) interacted with a trained confederate; partners answered a series of increasingly intimate questions about themselves. Participant ES for positive and negative emotions, and participant and confederate DFI were collected during the task. Participants completed global anxiety, depression, and CT measures. CT correlated with positive (r=.35, p=.002), but not negative, ES (r=.13, p=.273). In a multiple linear regression model, CT predicted positive ES beyond symptom variables and gender, β=.318, t=2.59, p=.012. Positive ES correlated with participant (r=−.38, p=.001) and confederate DFI (r=−.40, p<.01); and predicted participant DFI beyond symptom variables and ethnicity, β=−.358, t=−3.18, p=.002, and confederate DFI, β=−.390, t=−3.51, p=.001, beyond symptom variables. Mediation analyses suggested positive ES accounted for the relationship between greater CT severity and less desire for future interaction from participants, 95%CI [−0.26,−0.02], and confederates, [−0.38, −0.01]. Positive ES may be an important factor in the reduced capacity to form new social relationships for individuals with a history of CT, anxiety, and depression.

Keywords: childhood trauma, anxiety, depression, social connection, expressive suppression, positive emotions

Social disconnection is common among individuals with anxiety and depression (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009; Saris et al., 2017). Adults with anxiety and/or depression frequently report loneliness as well as persistent impairments in social functioning (Cramer et al., 2005; McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). Experiencing childhood trauma (CT; i.e., abuse and/or neglect) is a well-established risk factor for many affective psychiatric outcomes in adulthood, including anxiety and depression, and can create barriers for developing relationships throughout the life course (Copeland et al., 2018). CT often involves disruption in affective regulation. In healthy development and within the context of consistent and supportive caretaking, children learn to internalize the perceptions and expectations of others and develop beneficial emotion regulation skills (Bowlby, 1988). Adults who report a history of CT, however, tend to endorse an insecure attachment style in which there is difficulty relating to others and regulating affect (Breidenstine et al., 2011). The compromised development of appropriate emotion regulation skills following CT increases the likelihood an individual’s emotional resources will be ineffective when encountering new interpersonal challenges, such as meeting new people and fostering new relationships (Briere, 1996). CT could thus interfere with the development of interpersonal connectedness, including the desire for affiliation, and lead to poorer interpersonal outcomes in adulthood. Consistent with this idea, adult survivors of CT report greater relationship dissatisfaction (Fleming et al., 1999), less interpersonal intimacy (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, 2000; Drapeau & Perry, 2004; Ducharme et al., 1997), less social support (Muller et al., 2008), and fewer friends and social contacts (Abdulrehman & DeLuca, 2001; Berlin et al., 2011) than adults without CT history.

An accumulating body of literature points to emotion regulation difficulties as mechanisms through which CT may contribute to poor social functioning and social quality of life in adults (Cloitre et al., 2002; Cloitre et al., 2005; Dvir et al., 2014; Rellini et al., 2012). One emotion regulation strategy particularly relevant to relationship formation is expressive suppression (ES). ES is a social-communicative strategy that involves attempts to block observable signs of one’s felt emotional experience (Gross & John, 2003). Prior research in nonclinical adult samples supports the notion that ES decreases interpersonal closeness (Butler et al., 2003; English et al., 2012; Gross & John, 2003; Impett et al., 2012; Srivastava et al., 2009) and is associated with lower social well-being and satisfaction (see Chervonsky & Hunt, 2017, for a meta-analytic review). Similar patterns exist within samples of individuals with anxiety and/or depression in which greater use of ES is linked with poorer social outcomes, such as fewer positive social events, less social support, and poorer quality friendships (Dryman & Heimberg, 2018; Farmer & Kashdan, 2012; Kashdan & Breen, 2008; Spokas et al., 2009). Thus, it is plausible that ES may be of particular importance in understanding the pathway between CT exposure and poorer relationship formation outcomes in adults with anxiety and/or depression.

To better understand the role of ES in relationship formation, several studies utilized experimental dyadic paradigms in unacquainted conversational partners. These paradigms involved manipulated emotion regulation strategy conditions in the context of discussing distressing topics such as the aftermath of nuclear war (Butler et al., 2003; Butler et al., 2007; Peters et al., 2014). One participant in each pair was instructed to use a given emotion regulation strategy (i.e., ES, cognitive reappraisal, or natural response) throughout the conversation, whereas the other participant remained uninstructed. Across studies that used these tasks, uninstructed participants in the ES dyad displayed heightened perceived threat (Peters et al., 2014), rated their partners as more hostile and withdrawn (Butler et al., 2007), reported less feelings of affiliation towards their partner (Butler et al., 2003; Butler et al., 2007), and rated their partners as worse interpersonal communicators (Peters et al., 2014) following the conversation. Results support the view that ES may precipitate negative outcomes, such as impaired interpersonal communication, reduced rapport, and inhibited social affiliation processes that are crucial for cultivating new relationships.

Several unresolved issues remain. First, prior studies utilized nonstandardized paradigms in which each dyad consisted of two participants. Different behaviors from both sides of the dyad could potentially unbalance the levels of ES and affiliation for each target individual and obscure interpretation of outcomes. Participants who were instructed to suppress emotions may have displayed responses that were biased by how their partner responded to them. In addition, the relation between ES and interpersonal outcomes was examined within the context of discussing distressing topics—a distinct social context from those wherein relationships are more likely to develop. Prior research also rarely dissociates ES of positive emotions from negative emotions. This is important given evidence of the unique roles positive (e.g., promote approach behaviors; signals for rewards) and negative (e.g., avoidant behaviors; signals for danger) emotions play in subjective well-being and social connection (Alexander et al., 2021; Fredrickson, 2001; Kuppens et al., 2008). Although the link between social affiliation and engagement in ES is well established, no studies have examined the association between social affiliation and engagement in ES during a dyadic interaction within clinical samples or samples with known CT history.

To address these gaps and extend prior research, the current study analyzed data from a standardized, confederate-controlled dyadic paradigm specifically intended to induce social affiliation between unacquainted partners during which participants rated their suppression of positive and negative emotions throughout the task. By controlling one half of the dyad, the current study could examine whether the act of ES itself had intrapersonal effects (i.e., influences on one’s own desire for future affiliation), in addition to interpersonal effects (i.e., influences on one’s partner’s desire for future affiliation). The current study aimed to (1) determine the associations between CT severity and within-task positive and negative ES in a clinical sample of adults with anxiety and/or depression, (2) contingently examine the association between within-task ES and social affiliation, and (3) contingently assess the effects of CT severity on participants’ and confederates’ desire for future affiliation through ES during the task.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 77 individuals between the ages of 18 and 55 meeting diagnostic criteria for a depressive or anxiety disorder who were enrolled in one of two studies: (1) an observational study that selected for participants with elevated social anxiety on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987) as indicated by a total score of ≥ 50 (n = 17) and (2) a clinical trial that selected for participants with clinically elevated symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, defined as scoring 10 or higher on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) and/or scoring 8 or higher on the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS; Norman et al., 2006; n = 60). Participants were recruited through clinical referrals as well as posted announcements in community and online settings (e.g., ResearchMatch.org).

Assessments to determine principal and comorbid diagnoses were conducted using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998, Version 5.0.0 or 7.0.0) by a Ph.D. student in clinical psychology and postbaccalaureate clinical research coordinators, all of whom received extensive training in the interview protocols. Diagnostic consensus was reached by reviewing completed interviews during team meetings with the corresponding author. Exclusionary criteria across the samples used to determine parent study eligibility were: (1) active suicidal ideation with intent or plan; (2) moderate to severe alcohol or marijuana use disorder (past year); (3) all other mild substance use disorders (past year); (4) bipolar I or psychotic disorders; (5) moderate to severe traumatic brain injury with evidence of neurological deficits, neurological disorders, or severe or unstable medical conditions that might be compromised by participation in the study; (6) inability to speak or understand English; (7) concurrent psychotherapy (unless 12-week stability criteria had been met for non-empirically-supported therapies only); (8) concurrent psychotropic medication (e.g., SSRIs, benzodiazepines); and (9) characteristics that would compromise safety to complete an MRI scan (e.g., metal fragments in body). The sample had a mean age of 28.64 years (SD = 9.03), was predominantly female (65.7%), and demographically diverse. See Table 1 for additional participant demographics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Study 1 (n = 17) |

Study 2 (n = 60) |

Full Sample (N = 77) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or % | M(SD) or % | M(SD) or % | |

| Age | 25.71 (6.28) | 29.47 (9.55) | 28.64 (9.03) |

| Gendera | |||

| Female | 64.7 | 68.3 | 67.5 |

| Male | 29.4 | 30.0 | 29.9 |

| Education (years) | 15.53 (2.29) | 15.63 (2.24) | 15.61 (2.24) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 11.8 | 21.7 | 19.5 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 88.2 | 78.3 | 80.5 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 23.5 | 26.7 | 26.0 |

| Black | 11.8 | 1.7 | 3.9 |

| White | 52.9 | 63.3 | 61.0 |

| More than one race/Other | 11.8 | 8.3 | 9.1 |

| Primary Clinical Diagnosis | |||

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 76.5 | 35.6 | 44.7 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 17.6 | 30.5 | 27.6 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 0.0 | 23.7 | 18.4 |

| Other diagnosis | 5.9 | 10.2 | 9.3 |

| OASIS | 10.18 (2.92) | 10.55 (2.94) | 10.48 (2.92) |

| PHQ-9 | 10.94 (6.79) | 12.40 (4.94) | 12.08 (5.38) |

| CTQ Total Score | 46.41 (20.27) | 54.62 (8.75) | 52.81 (12.56) |

Note. OASIS = Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire- 9; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

One participant in Study 1 and one participant in Study 2 did not identify their gender as female or male.

Procedure

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of California San Diego Human Research Protection Program and with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). All participants provided informed written consent before participating in the study. After completing the eligibility assessment, participants completed self-report measures and the social affiliation paradigm on a separate visit.

Social affiliation paradigm

The current study utilized a modified version of the task developed by Aron et al. (1997). A detailed description of the paradigm and its psychometric properties is reported in Hoffman et al. (2021). Participants and trained confederates alternated responses to a series of three 6-minute question sets with each question set gradually increasing in intimacy level. An experimenter informed the participant they would be getting to know an assistant who worked in the lab (i.e., the confederate) before the start of the task. With the confederate present, the experimenter stated that the purpose of the task was to get to know one another by answering a series of questions about themselves. Each interaction started with the confederate reading aloud and answering the first question, followed by the participant’s response to the same question. The participant responded first to the next question, followed by the confederate response (and so on). Participants and confederates completed ratings following each question set (described below) on a separate form and out of their partner’s sight. The interaction lasted 18 minutes. A description of personnel and confederate training is presented in the Supplemental Materials.

Measures

Childhood Trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 2003) is the most widely used measure of childhood trauma. It has acceptable internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and strong convergence with interviews that assess child trauma (Bernstein et al., 2003). The CTQ contains 28 items and assesses five types of maltreatment experiences (i.e., emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect). A 5-point Likert-scale is used to assess the severity of each type of experience ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). Each domain can be summed together for a total maltreatment score. Given the sample size in the current study, only the summed total score was used as an independent variable in regression analyses to avoid multiple comparisons. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was α = .84.

Expressive Suppression

Immediately after each 6-minute question set during the social affiliation task, participants rated the following questions: “When I was feeling positive emotions, I was careful not to express them” and “When I was feeling negative emotions, I was careful not to express them.” Participants rated their response on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely; Gross & John, 2003; Kashdan & Breen, 2008).1

Social Affiliation

Upon completion of the task, participants and confederates completed the Desire for Future Interaction Scale (DFI; Coyne, 1976). The DFI assesses the extent to which the rater (participant or confederate) would be willing to engage in a variety of social activities with their interaction partner in the future (sample items: “Would you like to spend more time with a person like this in the future?”; “Would you like to have a person like this as a friend?”). Eight items are rated from 1 (not at all) and 7 (very much). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was α = .95.

Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the OASIS (Bragdon et al., 2016; Moore et al. 2015; Norman et al., 2006; Norman et al., 2011). The OASIS is a transdiagnostic measure of the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms, as well as the level of anxiety-based avoidance and interference during the previous two weeks. Five items range from 0 (never/none/not at all) to 4 (constantly/extreme/all the time). The sample’s average OASIS score (M = 10.47, SD = 2.92) indicated moderate levels of anxiety severity. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was α = .79.

Depressive symptom severity during the past 2 weeks based on DSM-5 symptom criteria was measured using the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001). The PHQ-9 consists of nine items ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The sample’s average PHQ-9 score (M = 12.08, SD = 5.38) indicated moderate levels of depression symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was α = .83.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS, Version 26. Average levels of positive and negative ES during the social affiliation task were computed separately for each participant. Multivariate outliers of study variables were screened by examining standardized residuals (± 3), Mahalanobis distance, χ2(4) > 18.47, and Cook’s distance (>1; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). No multivariate outliers were identified. Bivariate correlations between positive and negative ES, CT severity, participant and confederate DFI, demographic variables (age, gender, years of education, ethnicity [Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic]), and anxiety and depression symptoms were first examined. Then, CT severity was contingently entered as an independent variable into a multiple linear regression model predicting positive ES, while adjusting for any significant demographic covariates and/or symptoms of anxiety and depression. Separate multiple linear regression models with participant and confederate DFI entered as dependent variables and positive and negative ES entered as independent variables, while adjusting for any significant demographic covariates and/or symptoms of anxiety and depression were also analyzed. The assumptions of normality (predicted-probability plot), linearity, homoscedasticity (residual plots), and multicollinearity (variance inflation factor < 5.00) were tested and confirmed. Pending significant associations between CT severity and positive and/or negative ES, we conducted separate simple unmoderated mediation models using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012) to assess the effect of childhood trauma severity (X) on participants’ and confederates’ total DFI score (Y) through ES (M) during the task. The indirect effects were tested using a bootstrap estimation approach with 5,000 samples.

Results

Bivariate correlations and statistical properties between study variables are presented in Table 2. Gender was significantly associated with CT (r = .24, p = .036), and ethnicity was significantly associated with participant DFI (r = .23, p = .047). There were no other significant associations between demographic variables (age, years of education, ethnicity), CT, participant and confederate DFI, and expressive suppression of positive and negative emotions (ps >.05). Positive ES and negative ES were moderately correlated (r = .35, p =.002), yet sufficiently distinct to examine them separately. CT was significantly correlated with average level of positive ES (r = .35, p = .002) but not average level of negative ES (r = .13, p = .273). The overall linear regression model predicting positive ES was significant, F(4, 72) = 3.13, p = .020, R2 = .148, ƒ2 = .174. CT severity remained a significant predictor of positive ES during the task even after adjusting for gender, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms, β = .32, t = 2.59, p = .012 (see Table 3). Average level of positive ES was negatively correlated with participant DFI (r = −.38, p = .001) and confederate DFI (r = −.40, p < .01). Average level of positive ES remained a significant predictor of participant DFI, β = −.33, t = −2.93, p = .005, when adjusting for ethnicity, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms. Average level of positive ES remained a significant predictor of confederate DFI, β = −.38, t = −3.34, p = .001, when adjusting for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Average level of negative ES was negatively related to participant DFI (r = −.38, p = .001), but not related to confederate DFI (r = −.15, p = .200). Negative ES remained a significant predictor of participant DFI when adjusting for ethnicity, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms, β = −.34, t = −3.13, p = .003. Results of the separate adjusted linear regression models predicting participant and confederate DFI are presented in Table 4.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlation Between Study Variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CTQ Total | 52.81 | 12.56 | — | ||||||

| 2. Positive expressive suppression | 20.51 | 22.57 | .35** | — | |||||

| 3. Negative expressive suppression | 48.31 | 34.35 | .13 | .35** | — | ||||

| 4. Participant DFI | 39.03 | 10.27 | −.15 | −.38** | −.38** | — | |||

| 5. Confederate DFI | 37.91 | 12.27 | .07 | −.40*** | −.15 | .26* | — | ||

| 6. OASIS | 10.48 | 2.92 | .38** | .25* | .10 | −.16 | −.09 | — | |

| 7. PHQ-9 | 12.08 | 5.38 | .32** | .17 | .13 | −.10 | .02 | .47*** | — |

Note. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DFI = Desire for Future Interaction scale; OASIS = Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Adjusted Linear Regression Model of Childhood Trauma Predicting Positive Emotion Suppression During the Social Affiliation Task

| Variable | B | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Constant | −12.86 | 13.22 | −39.20 | 13.49 | −0.97 | .334 | |

| CTQ | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 1.01 | .32 | 2.59 | .012 |

| Gender | −5.04 | 5.15 | −15.31 | 5.22 | −.11 | −0.98 | .331 |

| OASIS | 1.19 | 1.01 | −0.82 | 3.19 | .15 | 1.18 | .241 |

| PHQ-9 | −0.04 | 0.54 | −1.11 | 1.02 | −.01 | −0.08 | .936 |

Note. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; OASIS = Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Table 4.

Adjusted Linear Regression Models of Expressive Suppression Predicting Desire for Future Interaction During the Social Affiliation Task

| Dependent Variable: | Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | β | t | p | R 2 | ƒ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | |||||||||

| Participant DFI | .006 | .180 | .220 | |||||||

| Constant | 44.24 | 4.17 | 35.93 | 52.56 | 10.61 | <.001 | ||||

| Positive ES | −0.15 | 0.05 | −0.25 | −0.05 | −.33 | −2.93 | .005 | |||

| Ethnicity | 4.91 | 2.85 | −0.77 | 10.59 | .19 | 1.72 | .089 | |||

| OASIS | −0.38 | 0.44 | −1.26 | 0.50 | −.11 | −0.86 | .393 | |||

| PHQ−9 | 0.07 | 0.24 | −0.40 | 0.54 | .04 | 0.29 | .770 | |||

| .004 | .192 | .238 | ||||||||

| Constant | 47.80 | 4.30 | 39.23 | 56.38 | 11.11 | <.001 | ||||

| Negative ES | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.17 | −0.04 | −.34 | −3.13 | .003 | |||

| Ethnicity | 4.96 | 2.82 | −0.66 | 10.59 | .19 | 1.76 | .083 | |||

| OASIS | −0.57 | 0.43 | −1.43 | 0.28 | −.16 | −1.35 | .183 | |||

| PHQ−9 | 0.10 | 0.23 | −0.37 | 0.56 | .05 | 0.40 | .687 | |||

| Confederate DFI | .004 | .165 | .198 | |||||||

| Constant | 41.55 | 4.97 | 31.64 | 51.45 | 8.36 | <.001 | ||||

| Positive ES | −0.23 | 0.06 | −0.36 | −0.10 | −.40 | −3.61 | <.001 | |||

| OASIS | −0.12 | 0.52 | −1.17 | 0.92 | −.03 | −0.24 | .813 | |||

| PHQ−9 | 0.18 | 0.28 | −0.38 | 0.75 | .08 | 0.65 | .517 | |||

Note. LB = lower bound; UB = upper bound; ES = expressive suppression; DFI = Desire for Future Interaction Scale; OASIS = Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

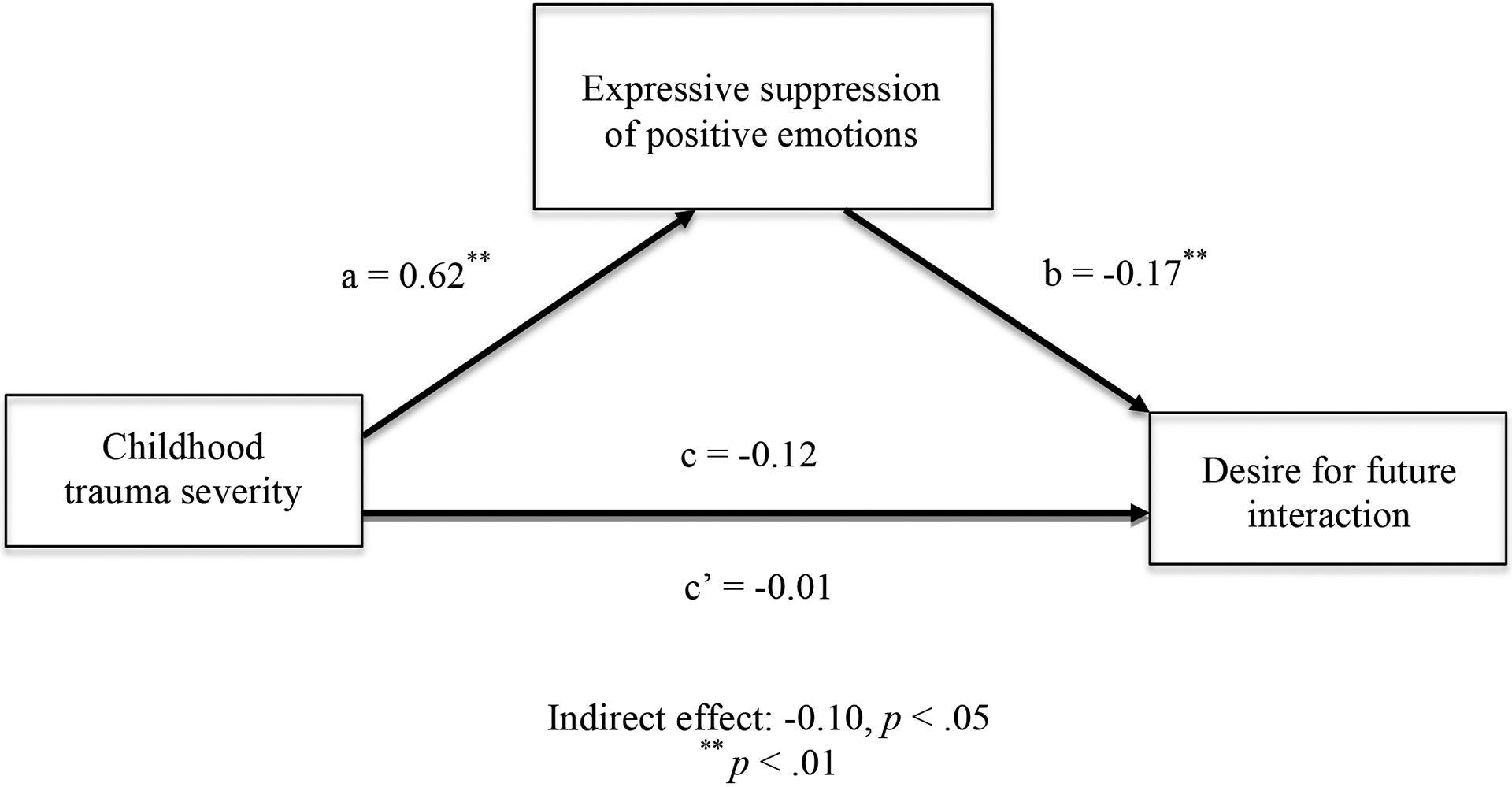

Mediation analysis

A mediation analysis indicated a statistically significant indirect effect of childhood trauma on participant DFI through expressive suppression of positive emotions, 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval [−0.26, −0.02]. Greater childhood trauma severity was associated with greater expressive suppression of positive emotions during the task, which was associated with less participant DFI. See Figure 1. Similarly, a second mediational model showed a significant indirect effect of childhood trauma on confederate DFI through positive ES [−0.38, −0.01]. That is, greater childhood trauma severity was associated with greater expressive suppression of positive emotions during the task, which was associated with less confederate DFI. See Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Indirect Effects Test of Childhood Trauma Severity on Participant Desire for Future Interaction via Expressive Suppression of Positive Emotions

Figure 2.

Indirect Effects Test of Childhood Trauma Severity on Confederate Desire for Future Interaction via Expressive Suppression of Positive Emotions

Discussion

The primary aim of the study was to better understand the relation between CT severity, ES, and social affiliation in a sample of adults with anxiety and/or depression. Our results showed that CT severity was associated with positive, but not negative, ES. Positive ES was negatively related to both participant and confederate DFI, whereas negative ES was only negatively related to participant DFI. All results remained consistent when controlling for demographic covariates and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Simple mediation analyses showed greater positive ES accounted for the link between greater CT severity and less desire for future interaction by both participants and confederates.

Use of ES is common in maltreated individuals (Balan et al., 2017; Ehring & Quack, 2010; Messman-Moore & Bhuptani, 2017; Moore et al., 2008; Weissman et al., 2019). Survivors of CT may utilize ES to cope with intense emotions stemming from challenging interpersonal circumstances. Whereas numerous studies have linked CT with ES of overall or negative emotions (Balan et al., 2017; Ehring & Quack, 2010; Messman-Moore & Bhuptani, 2017; Moore et al., 2008; Weissman et al., 2019), few studies to date have investigated the association between CT and ES of positive emotions. Results of the current study (i.e., that CT severity was associated with positive, but not negative, ES) are consistent with findings reported by Monde and colleagues (2013), who found that ability to subjectively suppress pleasant, but not unpleasant or neutral, emotion during an emotion regulation task was positively correlated with the CTQ total score in a combined sample of adult women with and without depersonalization disorder. The current study is the first to examine this relationship in the context of a dyadic task to better understand social affiliation. Individuals with greater CT severity may utilize positive ES for several reasons. Research indicates that individuals who engage in ES may appraise their positive emotions as unwanted or unacceptable, believe that they do not deserve to feel positive emotions, or do so to minimize attention towards themselves (Bishop & Reed, 2022; Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Goodman et al., 2018). Contrary to previous research, negative ES was not significantly related to CT in the current study. Future research that examines the relation between ES and CT across different social contexts is needed.

Results of the regression and mediational analyses indicated that positive ES was negatively related to both participant and confederate DFI and accounted for the relationship between greater CT severity and less DFI from both sides of the dyad. These findings support previous research linking greater use of ES (in general) with less social affiliation and poorer interpersonal outcomes (e.g., Butler et al., 2003; Gross & John, 2003; Impett et al., 2012; Peters et al., 2014; Peters & Jamieson, 2016). There are several mechanisms by which ES might interfere with social affiliation processes (i.e., DFI). Engaging in ES is effortful and may reduce availability of adaptive cognitive and coping resources otherwise used to facilitate reciprocal engagement during a social interaction (Kashdan et al., 2011). Research suggests that ES may degrade memory for what a conversation partner has said (Richards et al., 2003) and impair ability to interpret others’ emotions based on their facial expressions (Schneider et al., 2013). Engaging in positive ES, in particular, may discourage interpersonal affiliation from others. In contexts wherein expression of positive emotions is anticipated, this may lead individuals to form negative judgments about those who suppress (Tackman & Srivastava, 2016). In contrast, expression of positive emotions provides positive social cues (e.g., smiling) that signal an invitation for relationship development (Fredrickson, 2001; Pearlstein et al., 2019). Such cues can produce reciprocal behaviors that serve to create a self-perpetuating cycle of social connectedness between two individuals. Thus, engaging in positive ES when encountering new people may send uninviting messages that devaluates the other person’s incentives for further interaction. This idea is supported by the current study results that found positive ES to be positively associated with confederate-rated DFI, in addition to participant-rated DFI. Taken together, continued use of ES for positive emotions may translate into poorer ability to initiate and/or reciprocate affiliation processes from either side of the dyad that could ultimately exacerbate social disconnection. Negative ES was not significantly related to confederate DFI in the current study. In the same vein that individuals may expect others to display positive emotions in a new social interaction, individuals may not expect display of negative emotions. Although speculative, suppression of negative emotions may play a greater role in sustaining or deepening established relationships than in forming new relationships.

Several study limitations should be considered. Research suggests that differences in cultural norms and values have an impact on use of emotion regulation strategies, including ES. For example, ES may be more congruent with Eastern cultural social norms and considered less maladaptive than in Western cultural social norms (Hu et al., 2014). A meta-analysis indicated that the link between ES and psychological adjustment was stronger in Western culture than in Eastern culture (Hu et al., 2014), and current findings may therefore not generalize to non-Western culture. Importantly, ES can be beneficial and adaptive when applied in an appropriate context and/or used to maintain an existing relationship. It may be habitual and inflexible use of ES that ultimately contributes to psychopathology when other more effective and less costly emotion regulation strategies could be used instead (Chernovsky & Hunt, 2017; Gross, 2002). The current study examined ES in a specific social interaction context (i.e., unacquainted pairs instructed to get to know one another). More research is needed that examines this relation in other types of relationships (e.g., established relationships) and social contexts. Differences in confederate demographics (age, ethnicity, education) has the potential to influence findings. Prior research, however, indicated that the paradigm demonstrates strong psychometric properties and that a small amount (an estimated 1%) of variance in task-related outcomes was accounted for by confederates’ individual differences (Hoffman et al., 2021). It is important to note that the cross-sectional mediational models conducted within the current study are preliminary analyses that cannot establish temporal precedence or the causal mechanisms of the relationships. Given the limited sample size and cross-sectional nature of the present study, longitudinal research in larger samples is needed to determine the direction of causality.

Despite its limitations, this study adds to our understanding of the relation between CT and ES. The current research is novel in that it is the first to empirically examine this relationship within the context of a dyadic paradigm in a clinical sample of adults with anxiety and/or depression. There is mounting evidence that such individuals engage in more ES than those without psychopathology and trauma exposure, and that ES can compromise positive interpersonal outcomes. Given that poor interpersonal outcomes and social disconnection for anxious and depressed individuals can exacerbate and contribute to the maintenance of psychopathology (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009; Saris et al., 2017), maladaptive use of ES is a potentially valuable treatment target. Few evidence-based therapies for anxiety and depression explicitly target the expression of positive emotions, but therapeutic strategies such as mindfulness, acceptance, and behavioral activities geared towards increasing exposure to and intensity of positive emotions may allow for greater expression of positive emotions that promote improved social outcomes (Carl et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2020). Questions remain about the long-term interpersonal consequences of ES and effective intervention strategies for modifying inflexible use of ES as it relates to social connection and functioning within anxiety, depression, and CT samples.

Supplementary Material

Conflict of Interest:

Charles T. Taylor declares that in the past 3 years he has been a paid consultant for Bionomics and receives payment for editorial work for UpToDate and the journal Depression and Anxiety. Murray B. Stein declares that he has in the past 3 years received consulting income from Actelion, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Aptinyx, atai Life Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bionomics, BioXcel Therapeutics, Eisai, Clexio, EmpowerPharm, Engrail Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Roche/Genentech. Dr. Stein has stock options in Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals and EpiVario and receives payment for editorial work for UpToDate and the journals Biological Psychiatry and Depression and Anxiety. Samantha N. Hoffman declares no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the following individuals who helped make this research possible: Taylor Smith and Sarah Pearlstein for conducting diagnostic interviews and overseeing project management; Kim Potter, Alison Sweet, and Thomas Tsai for overseeing project management; and the many student volunteers who helped with developing study materials, participant recruitment, screening, data collection and management.

This research was supported by grants awarded to Charles T. Taylor from the National Institute of Mental Health (R61MH113769; R33MH113769). The project described was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, Grant ULTR001442 of CTSA funding beginning August 13, 2015 and beyond. The sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Participants rated other questions during the social affiliation task that are described in Hoffman et al. (2021).

Contributor Information

Samantha N. Hoffman, San Diego State University/University of California San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology

Murray B. Stein, University of California San Diego

Charles T. Taylor, University of California San Diego

References

- Abdulrehman RY, & De Luca RV (2001). The Implications of Childhood Sexual Abuse on Adult Social Behavior. Journal of Family Violence 16, 193–203. 10.1023/A:1011163020212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander R, Aragón OR, Bookwala J, Cherbuin N, Gatt JM, Kahrilas IJ, Kästner N, Lawrence A, Lowe L, Morrison RG, Mueller SC, Nusslock R, Papadelis C, Polnaszek KL, Richter SH, Silton RL, & Styliadis C (2021). The neuroscience of positive emotions and affect: Implications for cultivating happiness and wellbeing. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 121, 220–249. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Melinat E, Aron EN, Vallone RD, & Bator RJ (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4), 363–377. 10.1177/0146167297234003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balan R, Dobrean A, Roman GD, & Balazsi R (2017). Indirect effects of parenting practices on internalizing problems among adolescents: The role of expressive suppression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 40–47. 10.1007/s10826-016-0532-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, & Dodge KA (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, & Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop LS, & Reed KMP (2022). The integrated constructionist approach to emotions: A theoretical model for explaining alterations to positive emotional experiences in the aftermath of trauma. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 149, 10.1016/j.brat.2021.104008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bragdon LB, Diefenbach GJ, Hannan S, & Tolin DF (2016). Psychometric properties of the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 201, 112–115. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstine AS, Bailey LO, Zeanah CH, & Larrieu JA (2011). Attachment and trauma in early childhood: A review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 4, 274–290. 10.1080/19361521.2011.609155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J (1996). A self-trauma model for treating adult survivors of severe child abuse. In Briere J, Berliner L, Bulkley JA, Jenny C, & Reid T (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (pp. 140–157). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA, Egloff B, Wilhelm FH, Smith NC, Erickson EA, & Gross JJ (2003). The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion, 3(1), 48–67. 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA, Lee TL, & Gross JJ (2007). Emotion regulation and culture: are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific?. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 7(1), 30–48. 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH, Brown TA, & Hofmann SG (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1251–1263. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl JR, Soskin DP, Kerns C, & Barlow DH (2013). Positive emotion regulation in emotional disorders: a theoretical review. Clinical psychology review, 33(3), 343–360. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervonsky E, & Hunt C (2017). Suppression and expression of emotion in social and interpersonal outcomes: A meta-analysis. Emotion, 17(4), 669–683. 10.1037/emo0000270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, & Han H (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: a phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067–1074. 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Miranda R, Stovall-McClough KC, & Han H (2005). Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 119–124. 10.1016/S00057894(05)80060-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Hinesley J, Chan RF, Aberg KA, Fairbank JA, van den Oord E, & Costello EJ (2018). Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184493. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC (1976). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85(2), 186–193. 10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer V, Torgersen S, & Kringlen E (2005). Quality of life and anxiety disorders: a population study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193(3), 196–202. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000154836.22687.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JL, & Petretic-Jackson PA (2000). The impact of child sexual abuse on adult interpersonal functioning: A review and synthesis of the empirical literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(3), 291–328. 10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00010-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau M, & Perry JC (2004). Childhood trauma and adult interpersonal functioning: a study using the core conflictual relationship theme method (CCRT). Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(10), 1049–1066. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme J, Koverola C, & Battle P (1997). Intimacy development: The influence of abuse and gender. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12(4), 590–59 [Google Scholar]

- Dryman MT, & Heimberg RG (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: a systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 17–42. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir Y, Ford JD, Hill M, & Frazier JA (2014). Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22(3), 149–161. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, & Quack D (2010). Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: the role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behavior Therapy, 41(4), 587–598. 10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English T, John OP, Srivastava S, & Gross JJ (2012). Emotion Regulation and Peer Rated Social Functioning: A Four-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(6), 780–784. 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AS, & Kashdan TB (2012). Social anxiety and emotion regulation in daily life: Spillover effects on positive and negative social events. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41, 152–162. 10.1080/16506073.2012.666561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Mullen PE, Sibthorpe B, & Bammer G (1999). The long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse in Australian women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23(2), 145–159. 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00118-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman FR, Doorley JD, & Kashdan TB (2018). Well-being and psychopathology: A deep exploration into positive emotions, meaning and purpose in life, and social relationships. In Diener E, Oishi S, & Tay L (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers. https://www.nobascholar.com [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (2002). Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. 10.1017/s0048577201393198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hoffman SN, Thomas ML, Pearlstein SL, Kakaria S, Oveis C, Stein MB, & Taylor CT (2021). Psychometric Evaluation of a Controlled Social Affiliation Paradigm: Findings From Anxiety, Depressive Disorder, and Healthy Samples. Behavior Therapy, 52(6), 1464–1476. 10.1016/j.beth.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Zhang D, Wang J, Mistry R, Ran G, & Wang X (2014). Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: a meta-analysis review. Psychological Reports, 114(2), 341–362. 10.2466/03.20.PR0.114k22w4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Kogan A, English T, John O, Oveis C, Gordon AM, & Keltner D (2012). Suppression sours sacrifice: Emotional and relational costs of suppressing emotions in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 707–720. 10.1177/0146167212437249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & Breen WE (2008). Social anxiety and positive emotions: a prospective examination of a self-regulatory model with tendencies to suppress or express emotions as a moderating variable. Behavior Therapy, 39(1), 1–12. 10.1016/j.beth.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Weeks JW, & Savostyanova AA (2011). Whether, how, and when social anxiety shapes positive experiences and events: A self-regulatory framework and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 786–799. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Realo A, & Diener E (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 66–75. 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR (1987). Social phobia. Modern problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. 10.1159/000414022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE, & Kashdan TB (2009). The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clinical psychology Review, 29(3), 243–259. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, & Bhuptani PH (2017). A review of the long‐term impact of child maltreatment on posttraumatic stress disorder and its comorbidities: An emotion dysregulation perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(2), 154–169. 10.1111/cpsp.12193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monde KM, Ketay S, Giesbrecht T, Braun A, & Simeon D (2013). Preliminary physiological evidence for impaired emotion regulation in depersonalization disorder. Psychiatry Research, 209(2), 235–238. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Welch SS, Michonski J, Poquiz J, Osborne TL, Sayrs J, & Spanos A (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the Overall Anxiety Severity And Impairment Scale (OASIS) in individuals seeking outpatient specialty treatment for anxiety-related disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 463–470. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Zoellner LA, & Mollenholt N (2008). Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms?. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(9), 993–1000. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RT, Gragtmans K, & Baker R (2008). Childhood physical abuse, attachment, and adult social support: Test of a mediational model. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 40(2), 80–89. 10.1037/0008-400X.40.2.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Campbell-Sills L, Hitchcock CA, Sullivan S, Rochlin A, Wilkins KC, & Stein MB (2011). Psychometrics of a brief measure of anxiety to detect severity and impairment: the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(2), 262–268. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, & Stein MB (2006). Development and validation of an Overall Anxiety Severity And Impairment Scale (OASIS). Depression and Anxiety, 23(4), 245–249. 10.1002/da.20182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstein SL, Taylor CT, & Stein MB (2019). Facial affect and interpersonal affiliation: Displays of emotion during relationship formation in social anxiety disorder. Clinical psychological science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 7(4), 826–839. 10.1177/2167702619825857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BJ, & Jamieson JP (2016). The consequences of suppressing affective displays in romantic relationships: A challenge and threat perspective. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 16(7), 1050–1066. 10.1037/emo0000202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BJ, Overall NC, & Jamieson JP (2014). Physiological and cognitive consequences of suppressing and expressing emotion in dyadic interactions. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 94(1), 100–107. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellini AH, Vujanovic AA, Gilbert M, & Zvolensky MJ (2012). Childhood maltreatment and difficulties in emotion regulation: associations with sexual and relationship satisfaction among young adult women. Journal of Sex Research, 49(5), 434–442. 10.1080/00224499.2011.565430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Butler EA, & Gross JJ (2003). Emotion regulation in romantic relationships: The cognitive consequences of concealing feelings. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(5), 599–620. 10.1177/02654075030205002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saris I, Aghajani M, van der Werff S, van der Wee N, & Penninx B (2017). Social functioning in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 136(4), 352–361. 10.1111/acps.12774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KG, Hempel RJ, & Lynch TR (2013). That “poker face” just might lose you the game! The impact of expressive suppression and mimicry on sensitivity to facial expressions of emotion. Emotion, 13(5), 852–866. 10.1037/a0032847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, & Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59 Suppl 20, 22–57. https://www.psychiatrist.com/JCP/article/Pages/1998/v59s20/v59s2005.aspx [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spokas M, Luterek JA, & Heimberg RG (2009). Social anxiety and emotional suppression: the mediating role of beliefs. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(2), 283–291. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Tamir M, McGonigal KM, John OP, Gross JJ (2009). The social costs of emotional suppression: A prospective study of the transition to college. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 883–897. 10.1037/a0014755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Tackman AM, & Srivastava S (2016). Social responses to expressive suppression: The role of personality judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(4), 574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Pearlstein SL, Kakaria S, Lyubomirsky S, & Stein MB (2020). Enhancing Social Connectedness in Anxiety and Depression Through Amplification of Positivity: Preliminary Treatment Outcomes and Process of Change. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(4), 788–800. 10.1007/s10608-020-10102-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DG, Bitran D, Miller AB, Schaefer JD, Sheridan MA, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Difficulties with emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic mechanism linking child maltreatment with the emergence of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3), 899–915. 10.1017/S0954579419000348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.