Abstract

A cat was referred for investigation of a soft tissue mass caudal to the left mandible. Initial investigations suggested a malignant salivary gland tumour, and the mass was removed by extracapsular resection of the mandibular gland. Histopathology showed an oncocytoma within the salivary gland. An oncocytoma is a neoplastic transformation of oncocytes. Oncocytes are cells with a small nucleus and intense eosinophilic granular cytoplasm due to numerous mitochondria, which proliferate during ageing in exocrine and endocrine glandular tissues. Physiological proliferation occurs next to oncocytosis, oncocytoma, and oncocytic carcinoma. This is the first report of an oncocytoma in a feline mandibular salivary gland, and the first report of long-term survival after surgical removal.

In cats neoplasia of salivary glands is uncommon with a reported prevalence of 0.6% (Carberry et al 1988). The mandibular salivary gland is most commonly affected. Adenocarcinomas are reported most frequently, but other tumour types such as squamous cell carcinoma and adenoma have been described (Carberry et al 1988, Withrow 2001). This is the first description of an oncocytoma in the mandibular salivary gland of the cat with long-term follow-up.

An 11-year-old male castrated crossbred cat was presented to the Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals (Utrecht University, The Netherlands) with a solid mass caudal to the left mandible. The mass had been present for 6 months and proliferated slowly. The referring veterinarian had taken biopsies of the tumour for histology, but these were not diagnostic.

On presentation, the cat was bright and alert, and had a normal appetite. Physical examination revealed a firm mass, 4×4×3 cm, in the region of the left mandibular salivary gland and mandibular lymph nodes. Radiographic evaluation of the thorax showed no evidence of pulmonary metastases. Ultrasonography of the mass and local lymph nodes revealed an encapsulated mass that extended towards the carotid artery and that had a consistent regular structure throughout the tissue and no aberrant vascularisation. The submandibular lymph node was enlarged and contained dense areas with acoustic shadowing suggestive of mineralisation. Cytological examination of a percutaneous fine-needle aspirate (FNA) of the mass (Fig 1) revealed groups of epithelial cells with acinus formation, with crowding that was slightly suspect of malignancy. The cells showed features of malignancy including anisokaryosis, prominent nucleoli and a coarse chromatin pattern in the nuclei. Cytology of the mandibular lymph node showed no signs of metastasis. Adenocarcinoma was excluded, but malignancy was still suspected and resection of the mass was advised.

Fig 1.

Cytology of salivary gland, cat; groups of glandular tissue with acinic structures, slightly suspect of malignancy due to crowding, anisokaryosis, prominent and sometimes multiple nucleoli with a coarse chromatin pattern in the nuclei.

Surgical excision was carried out. Pre-medication consisted of 32 μg/kg medetomidine (Domitor; Pfizer) and 16 μg/kg buprenorphine (Temgesic; Roche). Anaesthesia for intubation was induced with 1 mg/kg propofol (Rapinovet; Fresenius) and maintained with oxygen and isoflurane (Isofluraan; Schering-Plough Animal Health). Analgesia was supplemented by 3 mg/kg carprofen (Rimadyl; Pfizer). Perioperative anti-microbial therapy consisted of intravenously administered 20 mg/kg amoxycillin/clavulanic acid (Augmentin; GlaxoSmithKline). The mass was approached using a horizontal elliptical skin incision so that the scar and biopsy tract could be removed en bloc with the gland. By the enlargement of the salivary gland the maxillary vein was moved to a more ventral position than physiologically expected, and there was even more close contact to maxillary vein than in the physiological situation. The mandibular salivary gland and the caudal part of the sublingual salivary gland were extirpated using an extracapsular technique. However, during dissection the capsule of the mandibular salivary gland was inadvertently ruptured twice on the lateral side. There were no macroscopic signs of invasive growth into surrounding structures beyond the capsule of the salivary gland. The wound was closed routinely. Postoperative treatment consisted of 12.5 mg/kg amoxycillin/clavulanic acid (Synulox; Pfizer) for 7 days and 1 mg/kg ketoprofen (Ketofen; Merial) for 3 days. After 28 months there were no signs of local recurrence during yearly physical examination by the referring veterinarian, and the cat was in good health.

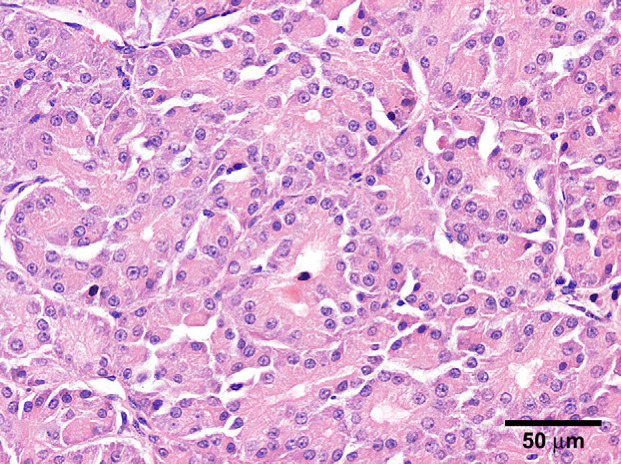

Histopathology was performed by the Department of Veterinary Pathobiology (Utrecht University, The Netherlands). Samples were fixed and processed routinely, and stained with haematoxylin–eosin (HE) for routine evaluation. Additional histochemical stains included phosphotungstic acid–haematoxylin (PTAH) to recognise mitochondria, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) to stain glycogen, alcian blue (AB) to identify mucin, and toluidine blue (TB) to detect mast cell granules. Grossly, the light-brown tumour consisted of two lobes, which were separated by fibrous tissue. The HE histology ( Fig 2) revealed a densely lobulated, well demarcated, partially and sparsely encapsulated neoplasm, accompanied by a few small foci of pre-existing mucinous glands. Thin fibrovascular tissue separated the lobules. The lobules were composed of polygonal to round epithelial cells, occasionally intermixed with acinar structures of varying size. The lumen of the acini contained homogenous eosinophilic material. The neoplastic epithelial cells had distinct cytoplasmatic borders and a finely granulated eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei were round to oval shaped and variably located. Within more solid islands, the nuclei were centrally placed, whereas in areas with acinar structures nuclei were basal. The nuclei contained one to two eosinophilic nucleoli. There were few isolated foci of lymphocytes and plasma cells also present. The PTAH staining for mitochondria (Fig 3) demonstrated dark blue granules within the cytoplasm of tumour cells. There was some variation in staining intensity, however, all tumour cells were positive, varying from mild to strong. The cytoplasm of tumour cells was also positive in the PAS staining indicating the presence of glycogen. The TB and AB stainings were negative within neoplastic areas, excluding a mast cell tumour or mucin production by tumour cells, respectively. The morphological and histochemical features were consistent with a diagnosis of oncocytoma (Head et al 2003).

Fig 2.

Salivary gland, cat; densely lobulated, medial to basal located nuclei, partially and sparsely encapsulated neoplasm [HE].

Fig 3.

Salivary gland, cat; tumour cells dark blue granules within the cytoplasm, diagnostic for multiple mitochondria [PTAH].

Oncocytoma is a neoplastic proliferation of oncocytes or oxyphilic cells. These cells are thought to originate from glandular epithelia of the head and neck and can be found in many endocrine and exocrine glands. They were first discovered by Hürtle in 1894 in normal canine thyroid glands (Capone et al 2002). Oncocytes are large, polygonal cells and have a small nucleus, and intense eosinophilic granular cytoplasm due to numerous mitochondria (typically 60% of entire cytoplasmic compartment), smooth endoplasmic reticulum, dense lysosome-like bodies and secretory granules (Berry et al 1988, Ellis and Auclair 1996, Paulino and Huvos 1999, Schindler et al 2001, Capone et al 2002, Head et al 2003). During ageing the presence of oncocytes or oncocytic metaplasia is nearly universal; oncocytes are found in the salivary tissue of 80% of people older than 70 years of age (Kontaxis et al 2004). The exact aetiopathogenesis of oncocytosis is unknown. It has been theorised that functional exhaustion of mitochondrial enzymes results in mitochondrial dysfunction and, therefore, a cellular defective metabolism caused by respiratory insufficiency. Mitochondrial proliferation is a compensatory mechanism to overcome the energy-deficient state. The origin of this dysfunction was sought in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which can occur during ageing. A mutation in the control region of the mtDNA was suspected, but in only one of 18 human oncocytic neoplasms of the parotid gland abnormality in the potentially responsible C-tract was found (Capone et al 2002). According to WHO histological classification on human oncocytic neoplasms, there are three categories of oncocytic proliferation: oncocytosis, oncocytoma and oncocytic carcinoma (Capone et al 2002). Ellis and Auclair (1996) and Kontaxis et al (2004) also differentiate oncocytosis into nodular or diffuse and suggested another category of adenomatous hyper- and metaplasia. Histologically the categories can be differentiated. In oncocytosis, the groups of oncocytes are not separated by stroma and diffuse infiltration of the surrounding normal tissue is seen. Adenomatous hyper- and metaplasia start at the ducts and are multifocal within normal salivary tissue, with stroma between the foci. The essential difference between oncocytoma, and oncocytosis and hyperplasia is the presence of a fibrous capsule (complete or incomplete) in cases of an oncocytoma, and the absence of a capsule in oncocytosis or hyperplasia (Ellis and Auclair 1996, Paulino and Huvos 1999, Kontaxis et al 2004). However, the distinction is often subtle; foci of adenomatous hyperplasia can be seen next to an oncocytoma. Sometimes micro- and/or macro-cysts can be seen in the tumour, with occasional clusters of lymphoid infiltrates. Oncocytic carcinoma is rarely seen in humans, in one series in only two out of 21 oncocytic neoplasms of the parotid gland (Capone et al 2002). The presence of oncocytic clear cells, in which intracellular glycogen deposition obscures eosinophilic granules, complicates sometimes the process of reaching a diagnosis (Ellis and Auclair 1996, Head et al 2003, Kontaxis et al 2004). Diagnosis of an oncocytoma by the use of cytology is difficult. In man the sensitivity of FNA diagnosis of salivary gland tumours is 62–97% (Schindler et al 2001). However, the sensitivity of cytological diagnosis of a parotid oncocytoma is only 29%; lack of interpreter experience and rarity of these tumours are possible reasons (Capone et al 2002). As oncocytosis is frequently seen in elderly people, FNA of a salivary mass may easily be misinterpreted as oncocytoma (Schindler et al 2001), but salivary (adeno)carcinoma may be excluded. The definitive diagnosis of salivary gland tumours is made by histopathology. The lack of staining in the AB reaction makes a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma highly unlikely. The absence of a reaction towards TB excludes a mast cell tumour. The characteristic features of oncocytomas are the abundant mitochondria, which are usually identified by a positive reaction in the PTAH stain, as was observed in this case. PTAH staining may not always be reliable, which can be improved by 48-h incubation (Ellis and Auclair 1996). Electron microscopy or use of anti-mitochondrial antibodies can even more readily demonstrate the mitochondria in the oncocytic cells, but is usually not necessary (Ellis and Auclair 1996, Paulino and Huvos 1999).

Oncocytomas in humans are usually benign, and are most often encountered in the pituitary gland, kidneys, or salivary glands (parotid, mandibular, or minor). The human parotid gland is the predominant site for salivary gland oncocytoma. The malignant variant of the tumour (oncocytic carcinoma) occurs more frequently in adrenals and thyroids (Paulino and Huvos 1999, Kontaxis et al 2004), but is also reported in the salivary glands (Capone et al 2002). In the dog and cat oncocytoma is an infrequently reported benign tumour. In the dog, this neoplasm has been reported in the larynx, kidney, nasal cavity, thyroid gland and parotid gland (Case and Simon 1966, Pass et al 1980, Bright et al 1984, Clercx et al 1996, Buergelt and Adjiri-Awere 2000, Dempster et al 2000, Morris and Dobson 2001). In the cat, there are three reports of oncocytomas: in a parotid gland (Case and Simon 1966), in the periocular region (Berry et al 1988) and in the nasal cavity (Doughty et al 2006). These cats were 5, 15 and 12 years old, respectively. All cats were managed by surgical excision and histopathological diagnosis of an oncocytoma with a benign histopathological appearance was made. Follow-up of these cats was 0–6 months after resection: one cat died postoperatively due to cardiac failure, one cat was euthanased after 6 months because of tumour recurrence, and one was lost to follow-up after resection of two local recurrences within a few months. In humans a recurrence rate of 20% is mentioned due to multifocal disease or incomplete excision (Capone et al 2002).

Malignancy was expected in the presented case due to the presence of several cytological characteristics of malignancy, but these were not characteristics for carcinoma. In this case report the tumour correlates to the characteristics of oncocytoma described by WHO (Head et al 2003), Ellis and Auclair (1996) and Kontaxis et al (2004), as there are fields of oncocytes divided by fibrovascular tissue, and the tumour is surrounded by an incomplete capsule. Former feline cases were diagnosed by HE staining (Case and Simon 1966), HE staining and electron microscopy (EM) (Berry et al 1988) and by immunohistochemical staining and EM (Doughty et al 2006).

This case is the first reported case of an oncocytoma in the mandibular salivary gland of a cat. Although the glandular capsule was ruptured twice during resection, the results of the long-term follow-up suggest benign tumour behaviour. Extracapsular excision of the mandibular salivary gland has resulted in a survival time of 28 months and no additional therapy has been needed in this period.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr E. Teske and Prof Dr A. Gröne for their contributions.

References

- Berry K.K., Wilson R.W., Holscher M.A., Crisp J. Oncocytoma in a cat, Companion Animal Practice 2, 1988, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bright R.M., Goring R.L., Calderwood-Mays M. Laryngeal neoplasia in two dogs, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 184, 1984, 738–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buergelt C.D., Adjiri-Awere A. Bilateral renal oncocytoma in a greyhound dog, Veterinary Pathology 37, 2000, 188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carberry C.A., Flanders J.A., Harvey H.J., Ryan A.M. Salivary gland tumours in dogs and cats: a literature and case review, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 24, 1988, 561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Capone R.B., Ha P.K., Westra W.H., Pilkington T.M., Sciubba J.J., Koch W.M., Cummings C.W. Oncocytic neoplasms of the parotid gland: a 16-year institutional review, Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery 126 (6), 2002, 657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case M.T., Simon J. Oncocytomas in a cat and a dog, Veterinary Medicine Small Animal Clinician 61, 1966, 41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clercx C., Wallon J., Gilbert S., Snaps F., Coignoul F. Imprint and brush cytology in the diagnosis of canine intranasal tumours, Journal of Small Animal Practice 37, 1996, 423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A.G., Delahunt B., Malthus A.W., St J., Wakefield J. The histology and growth kinetics of canine renal oncocytoma, Journal of Comparative Pathology 123, 2000, 294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty R.W., Brockman D., Neiger R., McKinney L. Nasal oncocytoma in a domestic shorthair cat, Veterinary Pathology 43 (5), 2006, 751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis G., Auclair P. Tumours of salivary glands, Atlas of Tumour Pathology 3rd series, fasc. 17, 1996, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, pp. 103–114 [Google Scholar]

- Head K.W., Cullen J.M., Dubielzig R., Else R.W., Misdorp W., Patnaik A.K., Tateyama S., van der Gaag I. Histological Classification of the Tumours of the Alimentary System of Domestic Animals, 2nd edn, 2003, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, pp. 60–61 [Google Scholar]

- Kontaxis A., Zanarotti U., Kainz J., Beham A. Die diffuse Onkozytose der Glandula Parotidea, Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 83, 2004, 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J., Dobson J. Small Animal Oncology, 1st edn, 2001, Blackwell Sciences: Oxford, pp. 144–145 [Google Scholar]

- Pass D.A., Huctable C.R., Cooper B.J., Watson E.D., Thompson R. Canine laryngeal oncocytomas, Veterinary Pathology 17, 1980, 672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulino A.M.D., Huvos A.G. Oncocytic and oncocytoid tumours of the salivary glands, Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology 16, 1999, 98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler S., Nayar R., Dutra J., Bedrossian C.W.M. Diagnostic challenges in aspiration cytology of the salivary glands, Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology 18 (2), 2001, 124–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withrow S.J. Cancer of the salivary glands. Withrow S.J. 3rd edn, Small Animal Clinical Oncology, 2001, WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 318–319. [Google Scholar]