Abstract

Background

We have previously developed an artificial intelligence–based risk assessment tool to identify the individual risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in a sexual health clinical setting. Based on this tool, this study aims to determine the optimal risk score thresholds to identify individuals at high risk for HIV/STIs.

Methods

Using 2008–2022 data from 216 252 HIV, 227 995 syphilis, 262 599 gonorrhea, and 320 355 chlamydia consultations at a sexual health center, we applied MySTIRisk machine learning models to estimate infection risk scores. Optimal cutoffs for determining high-risk individuals were determined using Youden's index.

Results

The HIV risk score cutoff for high risk was 0.56, with 86.0% sensitivity (95% CI, 82.9%–88.7%) and 65.6% specificity (95% CI, 65.4%–65.8%). Thirty-five percent of participants were classified as high risk, which accounted for 86% of HIV cases. The corresponding cutoffs were 0.49 for syphilis (sensitivity, 77.6%; 95% CI, 76.2%–78.9%; specificity, 78.1%; 95% CI, 77.9%–78.3%), 0.52 for gonorrhea (sensitivity, 78.3%; 95% CI, 77.6%–78.9%; specificity, 71.9%; 95% CI, 71.7%–72.0%), and 0.47 for chlamydia (sensitivity, 68.8%; 95% CI, 68.3%–69.4%; specificity, 63.7%; 95% CI, 63.5%–63.8%). High-risk groups identified using these thresholds accounted for 78% of syphilis, 78% of gonorrhea, and 69% of chlamydia cases. The odds of positivity were significantly higher in the high-risk group than otherwise across all infections: 11.4 (95% CI, 9.3–14.8) times for HIV, 12.3 (95% CI, 11.4–13.3) for syphilis, 9.2 (95% CI, 8.8–9.6) for gonorrhea, and 3.9 (95% CI, 3.8–4.0) for chlamydia.

Conclusions

Risk scores generated by the AI-based risk assessment tool MySTIRisk, together with Youden's index, are effective in determining high-risk subgroups for HIV/STIs. The thresholds can aid targeted HIV/STI screening and prevention.

Keywords: HIV, machine learning, risk assessment tool, sexually transmitted infections, STIs

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) remain a significant public health issue globally, with an estimated 376 million new cases of curable STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and trichomoniasis, occurring annually among sexually active individuals [1]. These STIs can lead to adverse health outcomes and substantial economic costs. Early detection and prompt treatment are crucial in reducing the spread of STIs and their associated health complications [2, 3]. However, many individuals delay or avoid seeking testing and treatment, often due to a lack of knowledge about their own risk for developing HIV/STIs, limited availability of testing services, and the social stigma attached to them [4–6].

To encourage early testing and diagnosis, risk prediction tools have been developed to help individuals assess their risk of acquiring HIV/STIs and to facilitate informed decisions on testing and treatment [7–9]. However, most available tools like SexPro and San Diego Early Test (SDET) predict HIV risk using logistic regression methodology, rather than providing concurrent assessments for other major STIs with more advanced algorithms [7–9]. Our recently optimized machine learning–based tool, MySTIRisk, aims to advance prediction through enhancing model performance for 4 major infections—HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea—and to conduct extensive user interface testing for effective risk communication [10].

While the development of risk prediction models has shown promise in identifying individuals at higher risk of acquiring HIV/STIs and providing targeted interventions, it is important to determine both the optimal cutoff point for these models and the appropriate recommendations for those not at high risk. If the cutoff point is set too high, then individuals not deemed to be “high risk” may not be tested, and if the cutoff point is set too low, then health services may be overwhelmed by individuals requesting unnecessary testing. Therefore, determining the cutoff point that achieves the best health expenditure and use of health outcomes is important.

Previous studies have used methods like receiver operating characteristic curves and Youden's index to derive optimal cutoff points [11–16]. However, the most appropriate technique remains uncertain and may depend on the model and population.

We utilized Youden's index to determine the optimal cutoff point for the risk scores generated by MySTIRisk, a recently developed machine learning– and web-based tool for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia risk prediction [17–19], in a population of individuals seeking STI testing at a community health clinic. We aimed to identify the optimal threshold that balances the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, allowing for accurate identification of individuals at high risk for HIV/STIs for tailored interventions and prioritization in resource-limited settings.

Our findings will inform the development of a public-facing web application of the MySTIRisk tool that can assist individuals in assessing their risk of contracting STIs and encourage early testing and diagnosis. This study also underscores the importance of using risk prediction tools to identify individuals at high risk and tailor interventions to those most at risk of acquiring HIV/STIs.

METHODS

Study Population

We used self-reported demographic and sexual behavioral data and laboratory-confirmed diagnoses from 167 451 individuals who attended the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC) between January 2008 and May 2022. The MSHC is Australia's largest public sexual health clinic, which offers free HIV/STI services to the general public [20]. Data were collected through computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) at initial and follow-up visits, with follow-up intervals of at least 3 months. CASI employed prestructured questionnaires filled out by participants, ensuring consistency and efficiency in data collection. Infection diagnoses were systematically recorded in the health record database using standardized fields [21].

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using data extracted from the electronic records of individuals who visited MSHC during the study period. The data sets for each infection included consultations where individuals were tested for specific infections at that consultation. The data sets for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia consisted of 216 252 (96 309 unique persons), 227 995 (100 230 unique persons), 262 599 (104 865 unique persons), and 320 355 consultations (139 634 unique persons), respectively.

Estimating the Risk Scores of HIV/STIs

We applied a risk prediction tool developed in a previous study to generate risk scores for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia [17, 18, 22]. MySTIRisk utilizes machine learning models trained on demographic, behavioral, and diagnostic data to estimate the risk scores from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the highest risk. The original models were trained and tested on 2015–2018 data, with area under the curve (AUC) values ranging from 0.70 to 0.84 across infections [18]. The key predictors included gender, age, country of birth, men who reported having sex with men, presence of STI symptoms, number of partners, condom use, injection drug use, past STIs, contact with STI diagnoses, and sexual partners outside Australia/New Zealand [18].

For the current study, we retrained the models using an expanded data set from January 2008 to May 2022 to improve model performance and ensure optimal results for the planned public website MySTIRisk [22]. However, we adhered to the same rigorous data-cleaning procedures to maintain the integrity and reliability of the expanded data set. Similar to the previous study, we utilized a 1-hot encoding scheme for data classification. No imputations were made for missing data; instead, a binary feature vector was employed to indicate the presence of missing values [18]. While detailed model performance metrics, such as AUC values, were not the central focus of this study and can be found in the supplementary tables for interested readers, the primary objective of this study was to determine the optimal risk score thresholds using Youden's index.

Determining the Optimal Threshold for HIV/STIs

The MSHC is currently developing a public-facing web application of the MySTIRisk tool [22] to assist individuals in assessing their risk of contracting HIV/STIs and encourage early testing and diagnosis.

To accurately identify individuals at high risk for HIV/STIs, we used Youden's index to determine the optimal threshold for our MySTIRisk model. Youden's index is a commonly used metric in medical research for determining the optimal cutoff point in diagnostic tests or risk prediction models [23, 24]. It considers both the sensitivity and specificity of the model, aiming to maximize both metrics simultaneously. The index is calculated as J = max (sensitivity + specificity – 1), where sensitivity is the proportion of true positives correctly identified, and specificity is the proportion of true negatives correctly identified. The optimal cutoff point is then the threshold with the highest Youden's index value. A value of 1 represents a perfect classification model, and a value of 0 represents a model that is no better than chance [23, 24].

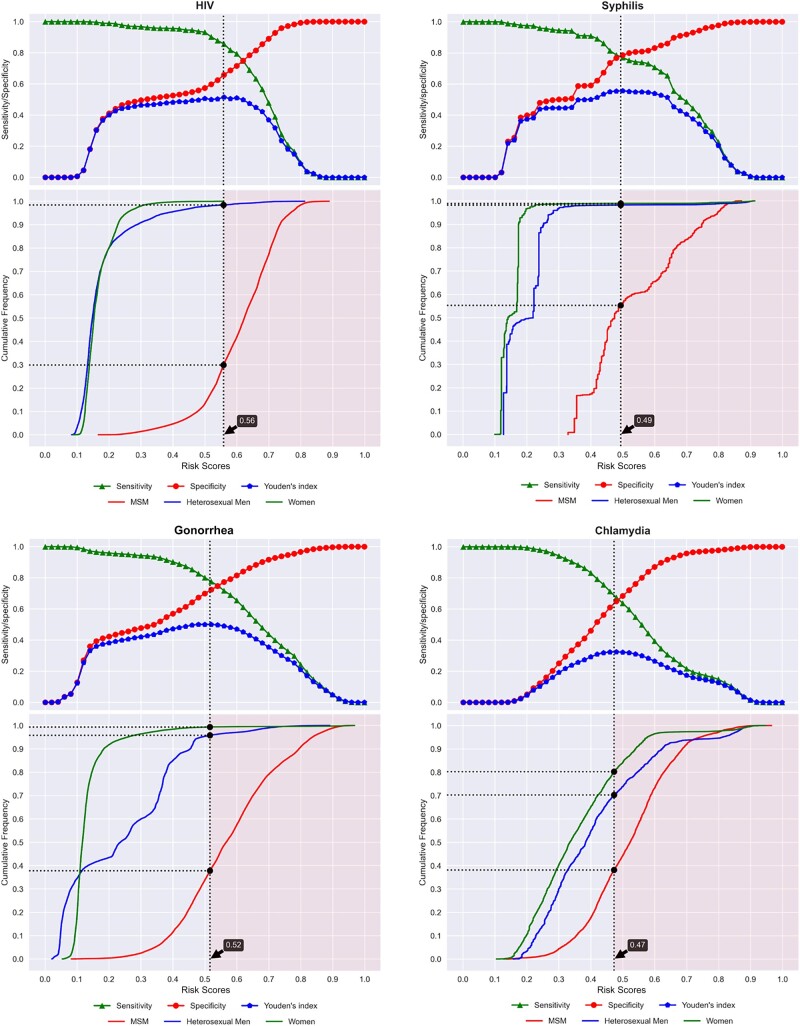

To identify the optimal cutoff points, we first calculated the risk scores for each consultation using the MySTIRisk models. We then evaluated a range of possible cutoff values at intervals of 0.02 from 0 to 1. For each potential cutoff, we computed the sensitivity, specificity, and Youden's index (sensitivity + specificity – 1). This allowed us to plot the sensitivity and specificity across the spectrum of cutoff values (Figure 1). We selected the risk score threshold that maximized Youden's index as the optimal cutoff point, balancing the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity for each infection. This data-driven approach allowed us to objectively determine the optimal cutoff points for the MySTIRisk models in identifying individuals at high risk for HIV/STIs in our clinic population.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, and Youden's index with optimal cut-off points for HIV/STIs

Youden's index was utilized as it considers both sensitivity and specificity equally to provide an objective and balanced threshold aligned with the study goal of effectively stratifying high- and average-risk groups based on subsequent positivity rates. Compared with the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, which focuses on model accuracy, Youden's index aligns more closely with our objective of discriminating between risk levels for targeted screening purposes.

Utilizing Youden's Index for Categorizing Risk Groups

After determining the optimal cutoff point for the machine learning models for HIV/STIs using Youden's index, we categorized the consultations into binary risk groups. Specifically, consultations with predicted risk scores at or above the optimal cutoff point were classified as “high risk” for contracting that infection. Meanwhile, those scoring below the optimal cutoff point were designated “average risk.” The proportion of individuals classified as high risk depends on Youden's index value and the distribution of scores in our data set.

Analysis of Risk Groups

We stratified consultations into high-risk and average-risk groups based on their risk scores for each infection. We then calculated the positivity rate within each risk group by determining the proportion of consultations testing positive. We also performed subgroup analyses to calculate positivity rates for specific populations, including men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexual males, and females. A large contrast in positivity rates between the risk groups would validate the risk classification. Additionally, we compared positivity between consultations for individuals on and not on HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). We also calculated unadjusted odds ratios comparing positivity rates between the high-risk and average-risk groups overall and between those on and not on PrEP. Unadjusted odds ratios were used for directly evaluating the performance of the risk categorization and matching the intended use of the tool for risk assessment.

All statistical analyses and model training were conducted using Python programming language (version 3.9.12).

Patient Consent

As this was a retrospective analysis of deidentified data, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the Ethics Committee.

Ethical Considerations

The Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee in Melbourne, Australia, granted ethical approval (project number: 124/18). The study was conducted in accordance with pertinent ethical regulations and guidelines.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

For each of the 4 infection data sets (HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia), which included all consultations tested for each infection, MSM accounted for the majority of consultations (40%–50%), followed by women (30%–36%) and heterosexual men (15%–25%). The median age for those with each of the 4 infections (interquartile range [IQR]) was 29 (25–36) years. In terms of country of birth, almost half (47%–49%) of the consultations were from participants born overseas, while the remaining consultations were from Australia and New Zealand. Table 1 also displays the sexual risk factors associated with each infection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Clinic Consultations in Individual Data Sets

| Predictors | HIV (n = 216 252 Consultations) |

Syphilis (n = 227 995 Consultations) |

Gonorrhea (n = 262 599 Consultations) |

Chlamydia (n = 320 355 Consultations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 29 (25–35) | 29 (25–36) | 29 (25–35) | 29 (25–35) |

| Country of birth, No. (%) | ||||

| Australia and New Zealand | 102 350 (47.3) | 108 755 (47.7) | 127 958 (48.7) | 155 603 (48.6) |

| Overseas | 104 085 (48.1) | 108 965 (47.8) | 122 357 (46.6) | 149 958 (46.8) |

| Missing | 9817 (4.5) | 10 275 (4.5) | 12 284 (4.7) | 14 794 (4.6) |

| Population type, No. (%) | ||||

| MSM | 105 616 (48.8) | 113 152 (49.6) | 127 500 (48.6) | 127 410 (39.8) |

| Heterosexual male | 43 716 (20.2) | 45 683 (20) | 40 099 (15.3) | 78 703 (24.6) |

| Female | 66 920 (30.9) | 69 160 (30.3) | 95 000 (36.2) | 114 242 (35.7) |

| Condom use with casual male partners, No. (%) | ||||

| Always | 40 759 (18.8) | 42 371 (18.6) | 50 959 (19.4) | 53 329 (16.6) |

| Sometimes | 90 136 (41.7) | 95 076 (41.7) | 114 329 (43.5) | 127 047 (39.7) |

| Never | 16 289 (7.5) | 17 584 (7.7) | 23 734 (9) | 25 462 (7.9) |

| Not applicable | 3752 (1.7) | 3967 (1.7) | 4720 (1.8) | 4860 (1.5) |

| Unsure/decline | 7896 (3.7) | 8966 (3.9) | 10 218 (3.9) | 10 640 (3.3) |

| Missing | 57 420 (26.6) | 60 031 (26.3) | 58 639 (22.3) | 99 017 (30.9) |

| Last time injected drugs not prescribed by doctor, No. (%) | ||||

| Never | 204 029 (94.3) | 213 820 (93.8) | 245 368 (93.4) | 301 328 (94.1) |

| <3 mo | 2588 (1.2) | 3070 (1.3) | 3535 (1.3) | 3785 (1.2) |

| Within 3–12 mo | 908 (0.4) | 1054 (0.5) | 1211 (0.5) | 1329 (0.4) |

| >12 mo | 2453 (1.1) | 2707 (1.2) | 3134 (1.2) | 3707 (1.2) |

| Decline/unsure | 4669 (2.2) | 5543 (2.4) | 6366 (2.4) | 6569 (2.1) |

| Missing | 1605 (0.7) | 1801 (0.8) | 2985 (1.1) | 3637 (1.1) |

| Having sex overseas, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 67 736 (31.3) | 70 411 (30.9) | 73 955 (28.2) | 98 778 (30.8) |

| No | 131 304 (60.7) | 138 757 (60.9) | 166 692 (63.5) | 197 698 (61.7) |

| Unsure | 10 638 (4.9) | 11 335 (5.0) | 12 744 (4.9) | 13 673 (4.3) |

| Missing | 6574 (3.0) | 7492 (3.3) | 9208 (3.5) | 10 206 (3.2) |

| Past history of gonorrhea, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 35 939 (16.6) | 39 599 (17.4) | 46 722 (17.8) | 46 193 (14.4) |

| No | 51 906 (24.0) | 56 334 (24.7) | 67 625 (25.8) | 82 874 (25.9) |

| Unsure | 3803 (1.8) | 3965 (1.7) | 4696 (1.8) | 5192 (1.6) |

| Missing | 124 604 (57.6) | 128 097 (56.2) | 143 556 (54.7) | 186 096 (58.1) |

| Past history of nonspecific urethritis, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 2412 (1.1) | 2718 (1.2) | 3608 (1.4) | 4092 (1.3) |

| No | 85 433 (39.5) | 93 215 (40.9) | 110 739 (42.2) | 124 975 (39.0) |

| Unsure | 3803 (1.8) | 3965 (1.7) | 4696 (1.8) | 5192 (1.6) |

| Missing | 124 604 (57.6) | 128 097 (56.2) | 143 556 (54.7) | 186 096 (58.1) |

| Past history of syphilis, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13149 (6.1) | 16 152 (7.1) | 17 366 (6.6) | 17 232 (5.4) |

| No | 74 696 (34.5) | 79 781 (35.0) | 96 981 (36.9) | 111 835 (34.9) |

| Unsure | 3803 (1.8) | 3965 (1.7) | 4696 (1.8) | 5192 (1.6) |

| Missing | 124 604 (57.6) | 128 097 (56.2) | 143 556 (54.7) | 186 096 (58.1) |

| Sexual contact with someone diagnosed with gonorrhea, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 4427 (2.0) | 4869 (2.1) | 6692 (2.5) | 6611 (2.1) |

| No | 211 825 (98.0) | 223 126 (97.9) | 255 907 (97.5) | 313 744 (97.9) |

| Sexual contact with someone diagnosed with chlamydia, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 6852 (3.2) | 7333 (3.2) | 9900 (3.8) | 13 327 (4.2) |

| No | 209 400 (96.8) | 220 662 (96.8) | 252 699 (96.2) | 307 028 (95.8) |

| Sexual contact with someone diagnosed with syphilis, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 2082 (1.0) | 2595 (1.1) | 2383 (0.9) | 2433 (0.8) |

| No | 214 170 (99.0) | 225 400 (98.9) | 260 216 (99.1) | 317 922 (99.2) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Risk Score Distribution for HIV/STI Data Sets

We calculated the median and IQR of the infection risk scores that were predicted for all individuals, which ranged from 0.00 (the lowest) to 1.00 (the highest) for HIV/STIs. The median risk scores and IQRs for all participants were 0.32 (0.15–0.62) for the HIV data set, 0.35 (0.16–0.47) for the syphilis data set, 0.37 (0.12–0.57) for the gonorrhea data set, and 0.42 (0.31–0.55) for the chlamydia data set (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk Score Distribution for HIV/STIs

| Overall, Median (IQR) |

HIV/STI-Positive Consultations, Median (IQR) |

HIV/STI-Negative Consultations, Median (IQR) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | 0.32 (0.15–0.62) | 0.70 (0.62–0.75) | 0.31 (0.15–0.62) |

| Syphilis | 0.35 (0.16–0.47) | 0.69 (0.53–0.80) | 0.30 (0.15–0.47) |

| Gonorrhea | 0.37 (0.12–0.57) | 0.67 (0.54–0.80) | 0.34 (0.12–0.54) |

| Chlamydia | 0.42 (0.31–0.55) | 0.56 (0.44–0.68) | 0.41 (0.30–0.54) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The Optimal Threshold for HIV/STIs

We determined the optimal cutoff thresholds for HIV/STIs for each infection by selecting the risk score cutoff points that maximized Youden's index, balancing sensitivity and specificity. We also identified the number of participants with HIV/STIs who had scores above the optimal threshold and alternative thresholds using quintile values (Supplementary Tables 1–4).

For HIV, the optimal cutoff point was at the risk score value of 0.56, which corresponded to a sensitivity of 86.0% (95% CI, 82.9%–88.7%), a specificity of 65.6% (95% CI, 65.4%–65.8%) and a Youden's index of 0.52. The cutoff classified 35% of individuals as high risk, with 86% of HIV infections found in the high-risk group.

For syphilis, the optimal cutoff point was at the risk score value of 0.49, with corresponding sensitivity and specificity values of 77.6% (95% CI, 76.2%–78.9%) and 78.1% (95% CI, 77.9%–78.3%), respectively, with a Youden's index of 0.56. The cutoff classified 23% of individuals as high risk, with 78% of syphilis infections found in the high-risk group.

For gonorrhea, the optimal cutoff point was at the risk score value of 0.52, with a sensitivity of 78.3% (95% CI, 77.6%–78.9%), a specificity of 71.9% (95% CI, 71.7%–72%), and a Youden's index of 0.50. The cutoff classified 31% of individuals as high risk, with 78% of gonorrhea infections found in the high-risk group.

For chlamydia, the optimal cutoff point was at the risk score value of 0.47, with a sensitivity of 68.8% (95% CI, 68.3%–69.4%), a specificity of 63.7% (95% CI, 63.5%–63.8%), and a Youden's index of 0.33. The cutoff classified 39% of individuals as high risk, with 69% of chlamydia infections found in the high-risk group.

Positivity Among the High-risk vs Average-risk Group

Overall positivity was highest for chlamydia (8.1%), followed by gonorrhea (5.9%), syphilis (1.7%), and HIV (0.3%). Positivity was highest among MSM across infections, while women had the lowest positivity. Importantly, testing recommendations vary for different groups, which influences overall positivity. The positivity in the high- and average-risk groups is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Positivity (the Positive Percentage of the HIV/STI Diagnosis) per Total Consultations

| Infection Positivity | Overall | High-risk | Average-risk | OR (95% CI) [High-risk vs Average-risk] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All High-risk | Not on PrEP | On PrEP | OR (95% CI) [No PrEP vs PrEP] |

All Average-risk | Not on PrEP | On PrEP | OR (95% CI) [No PrEP vs PrEP] |

|||

| HIV | ||||||||||

| All | 0.27% (593/216 252) |

0.68% (510/74 718) |

0.81% (495/61 067) |

0.11% (15/13 651) |

7.43 (4.44–12.42) |

0.06% (83/141 534) |

0.06% (82/136 248) |

0.02% (1/5286) |

3.18 (0.44–22.85) |

11.71 (9.28–14.77) |

| Population groups | ||||||||||

| MSM | 0.52% (548/105 616) |

0.67% (498/74 040) |

0.8% (483/60 394) |

0.11% (15/13 646) |

7.33 (4.38–12.26) |

0.16% (50/31 576) |

0.19% (49/26 373) |

0.02% (1/5203) |

9.68 (1.34–70.12) |

4.27 (3.19–5.71) |

| Heterosexual male | 0.07% (31/43 716) |

1.77% (12/678) |

1.78% (12/673) |

0.00% (0/5) |

NA | 0.04% (19/43 038) |

0.04% (19/42 994) |

0.00% (0/44) |

NA | 40.8 (19.73–84.39) |

| Female | 0.02% (14/66 920) |

- | - | - | - | 0.02% (14/66 920) |

0.02% (14/66 881) |

0.00% (0/39) |

NA | NA |

| Syphilis | ||||||||||

| All | 1.71% (3894/227 995) |

5.79% (3020/52 123) |

5.93% (2377/40 078) |

5.34% (643/12 045) |

1.12 (1.02–1.22) |

0.50% (874/175 872) |

0.45% (747/167 637) |

1.54% (127/8235) |

0.29 (0.24–0.35) |

12.31 (11.41–13.28) |

| Population groups | ||||||||||

| MSM | 3.02% (3417/113 152) |

5.48% (2773/50 592) |

5.53% (2132/38 559) |

5.33% (641/12 033) |

1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

1.03% (644/62 560) |

0.95% (518/54 427) |

1.55% (126/8133) |

0.61 (0.50–0.74) |

5.58 (5.12–6.08) |

| Heterosexual male | 0.67% (304/45 683) |

18.6% (149/801) |

18.49% (147/795) |

33.33% (2/6) |

0.45 (0.08–2.48) |

0.35% (155/44 882) |

0.34% (154/44 817) |

1.54% (1/65) |

0.22 (0.03–1.6) |

65.94 (51.99–83.64) |

| Female | 0.25% (173/69 160) |

13.42% (98/730) |

13.54% (98/724) |

0.00% (0/6) |

NA | 0.11% (75/68 430) |

0.11% (75/68 393) |

0.00% (0/37) |

NA | 141.32 (103.58–192.82) |

| Gonorrhea | ||||||||||

| All | 5.89% (15 461/262 599) |

14.82% (12 099/81 632) |

14.14% (8974/63 448) |

17.19% (3125/18 184) |

0.79 (0.76–0.83) |

1.86% (3362/180 967) |

1.78% (3129/176 064) |

4.75% (233/4903) |

0.36 (0.31–0.41) |

9.19 (8.84–9.56) |

| Population groups | ||||||||||

| MSM | 10.46% (13 338/127 500) |

14.60% (11 577/79 315) |

13.83% (8455/61 142) |

17.18% (3122/18 173) |

0.77 (0.74–0.81) |

3.65% (1761/48 185) |

3.53% (1532/43 391) |

4.78% (229/4794) |

0.73 (0.63–0.84) |

4.51 (4.28–4.75) |

| Heterosexual male | 2.42% (972/40 099) |

17.19% (291/1693) |

17.12% (288/1682) |

27.27% (3/11) |

0.55 (0.15–2.09) |

1.77% (681/38 406) |

1.77% (679/38 349) |

3.51% (2/57) |

0.50 (0.12–2.05) |

11.50 (9.93–13.32) |

| Female | 1.21% (1151/95 000) |

37.02% (231/624) |

37.02% (231/624) |

- | - | 0.97% (920/94 376) |

0.97% (918/94 324) |

3.85% (2/52) |

0.25 (0.06–1.03) |

59.71 (50.12–71.13) |

| Chlamydia | ||||||||||

| All | 8.08% (25 870/320 355) |

14.27% (17 811/124 829) |

13.85% (14 722/106 269) |

16.64% (3089/18 560) |

0.81 (0.78–0.85) |

4.12% (8059/195 526) |

4.07% (7781/191 375) |

6.70% (278/4151) |

0.59 (0.52–0.67) |

3.87 (3.77–3.98) |

| Population groups | ||||||||||

| MSM | 10.32% (13 148/127 410) |

13.51% (10 649/78 821) |

12.55% (7567/60 302) |

16.64% (3082/18 519) |

0.72 (0.69–0.75) |

5.14% (2499/48 589) |

4.99% (2223/44 533) |

6.80% (276/4056) |

0.72 (0.63–0.82) |

2.88 (2.75–3.01) |

| Heterosexual male | 7.95% (6257/78 703) |

16.66% (3901/23 420) |

16.65% (3896/23 395) |

20.00% (5/25) |

0.80 (0.30–2.13) |

4.26% (2356/55 283) |

4.26% (2355/55 225) |

1.72% (1/58) |

2.54 (0.35–18.35) |

4.49 (4.26–4.74) |

| Female | 5.66% (6465/114 242) |

14.44% (3261/22 588) |

14.44% (3259/22 572) |

12.5% (2/16) |

1.18 (0.27–5.19) |

3.50% (3204/91 654) |

3.50% (3203/91 617) |

2.70% (1/37) |

1.30 (0.18–9.48) |

4.66 (4.43–4.90) |

Abbreviations: MSM, men who have sex with men; OR, odds ratio; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The high-risk group had markedly higher positivity than the average-risk group across all 4 infections. The positivity in the high-risk group for HIV was 0.7%, which was 11.7 (95% CI, 9.3–14.8) higher odds than the average-risk group for HIV. The positivity rate in the high-risk group for syphilis was 5.8%, which was 12.3 (95% CI, 11.4–13.3) higher odds than the average-risk group for syphilis. The positivity rate in the high-risk group for gonorrhea was 14.8%, which was 9.2 (95% CI, 8.8–9.6) higher odds than the average-risk group for gonorrhea. The positivity rate in the high-risk group for chlamydia was 8.1%, which was 3.9 (95% CI, 3.8–4.0) higher odds than the average-risk group for chlamydia.

In the high-risk group, we found that individuals not taking HIV PrEP had 7.4 (95% CI, 4.4–12.4) times higher odds of being infected with HIV than those taking PrEP (0.8% vs 0.1%). Similarly, for syphilis in the high-risk group, we found that individuals not taking HIV PrEP had 1.1 (95% CI, 1.0–1.2) times higher odds of being infected with syphilis than those taking PrEP (6.0% vs 5.3%). For gonorrhea in the high-risk group, we found that individuals not taking HIV PrEP had 0.8 (95% CI, 0.76–0.8) times lower odds of being infected with gonorrhea than those taking HIV PrEP (14.1% vs 17.2%). For chlamydia in the high-risk group, we found that individuals not taking HIV PrEP had 0.8 (95% CI, 0.8–0.9) times lower odds of being infected with chlamydia than those on PrEP (13.9% vs 16.7%).

In the average-risk group, we found that individuals not on PrEP had 3.2 (95% CI, 0.4–22.9) times higher odds of being infected with HIV than those on PrEP (0.06% vs 0.02%). Similarly, for syphilis in the average-risk group, we found that individuals not on PrEP had 0.3 (95% CI, 0.2–0.6) times lower odds of being infected with syphilis than those on PrEP (0.5% vs 1.5%). For gonorrhea in the average-risk group, we found that individuals not on PrEP had 0.4 (95% CI, 0.3–0.4) times lower odds of being infected with gonorrhea than those on PrEP (1.8% vs 4.8%). For chlamydia in the average-risk group, we found that individuals not on PrEP had 0.6 (95% CI, 0.5–0.7) times lower odds of being infected with chlamydia than those on PrEP (4.1% vs 6.7%).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we utilized Youden's index to determine optimal cutoff points to identify individuals at high or average risk for HIV/STIs. We found substantially higher positivity in the high-risk groups across all 4 infections, indicated by substantially higher odds of positivity. This demonstrates the validity of the risk categorization and its ability to identify individuals based on the underlying risk. Additionally, while HIV positivity was higher in individuals who were not on PrEP compared with PrEP users, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia positivity showed the opposite pattern. This aligns with existing evidence on the preventive impact of PrEP for HIV vs other STIs [25, 26]. By accurately identifying individuals at high risk for HIV/STIs using a simple tool such as MySTIRisk, targeted interventions can be implemented in resource-limited settings, leading to more efficient use of limited resources. Our findings underscore the potential use of the optimized MySTIRisk thresholds for targeted sexual health interventions and resource allocation in HIV prevention and management contexts.

Our study identified optimal risk score thresholds that balanced sensitivity and specificity for each infection utilizing Youden's index. With these thresholds, the proportion of consultations that were classified as high risk was 23%–39% across the 4 infections. For all infections, most cases were detected in the high-risk groups, ranging from 69% of chlamydia cases to 86% of HIV cases. This approach allowed for objective determination of customized risk thresholds by finding the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity [23]. Our findings align with previous studies that derived optimal thresholds for STI risk models [11, 27]. Nieuwenburg et al. developed a symptom-based risk score calculator in the Netherlands using multivariable logistic regression models for MSM attending the Amsterdam Centre for Sexual Health. They determined the optimal cutoff point for infectious syphilis using Youden's index. Despite strong associations between symptoms and infectious syphilis, the symptom-based risk scores exhibited limited performance, with AUCs ranging from only 0.68 to 0.69, with a corresponding 41% sensitivity, 95% specificity, and Youden's index value of 0.46 [11]. Our optimal thresholds demonstrated improved discrimination compared with the Nieuwenburg et al. syphilis model while balancing the sensitivity and specificity trade-off central to STI screening optimization.

Another study focusing on the development and validation of a risk estimation tool for asymptomatic chlamydia and gonorrhea using multivariable logistic regression reported an AUC of 0.74, with a high sensitivity of 91% but a lower specificity of 32%, highlighting the complexities in optimizing screening tools for STIs. To determine the optimal cutoff point, this study analyzed the screening performance estimates at different cutoff levels of the sum scores, and the cutoff value with a fixed sensitivity of 91% was chosen as the optimal cutoff point [27]. Our study contributes to developing more effective STI screening tools by providing an alternative way to define high-risk populations, which can be used to inform targeted interventions and prioritize resources in clinical settings.

Our study demonstrated that the high-risk group had substantially higher positivity rates than the average-risk group across all 4 STIs, including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. The odds of positivity were found to be 3.9–12.3 times higher in the high-risk group than in the average-risk group. This significant difference in positivity demonstrates the validity of our risk categorization in identifying those most likely to have an infection. Accurately discriminating between high- and average-risk individuals using optimal thresholds is an important advance for targeted STI prevention and care. While all individuals should have access to sexual health services, identifying those at higher risk allows for more intensive interventions and resources to be directed to those who need it most. Our findings support the potential use of the MySTIRisk tool in assessing individual risk profiles to guide tailored responses.

Our study also demonstrated notable differences in positivity for HIV and other STIs between individuals using preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and those not using PrEP. Specifically, the odds of HIV positivity were 3 times higher among non-PrEP users than among PrEP users, highlighting the effectiveness of PrEP in reducing the risk of HIV infection [28]. In contrast, positivity for syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia was lower among non-PrEP users relative to PrEP users. This finding aligns with existing evidence on the preventive impact of PrEP for HIV vs other STIs [25, 26]. It underscores the importance of comprehensive sexual health strategies that include not only PrEP for HIV prevention but also regular testing and treatment for other STIs. It is crucial for individuals, especially those at higher risk of acquiring STIs, to be aware of their risk and take appropriate preventive measures, including consistent condom use and regular testing for HIV/STIs.

However, it is important to note that the risk tool developed in this study discriminates risk levels rather than defining absolute risk categories. Therefore, caution should be exercised in interpreting scores below the cutoff, implying no need for testing or prevention. Baseline testing and counseling should be recommended for all individuals in studies such as ours where the source of the individual is a high-risk setting such as an STI center, regardless of their risk score. It highlights the importance of comprehensive sexual health services that go beyond risk prediction models and consider individual circumstances and needs. Furthermore, it should be used to identify higher-risk individuals who may require more frequent or intensive services rather than opt out of services. Individuals with scores above the cutoff point should be considered a high priority for enhanced prevention and testing services due to their greater risk of infection relative to the clinic population. This can help tailor interventions and allocate resources effectively to those most in need.

The findings of our study have important policy implications and provide directions for future research. One significant contribution of this paper is the alternative way it proposes to define the high-risk population. Using machine learning algorithms and the risk scores for each infection, the study identifies individuals in the high-risk group. This information can help policy-makers and health care providers improve screening protocols and sexual health guidelines to better identify high-risk subgroups for enhanced testing and preventive interventions. Additional counseling, contact tracing, and treatment escalation can also be directed specifically to those individuals categorized by MySTIRisk as higher risk. Such targeted resource allocation and interventions could substantially reduce STI complications and health care costs at the population level by focusing additional testing on the minority of individuals at higher risk.

Future research should focus on investigating the expenses associated with HIV testing and the economic impacts of implementing predictive models like MySTIRisk. Understanding cost-effectiveness can further inform resource allocation and budget planning within sexual health programs to guide implementation decisions and policy responses to curb rising STI incidence.

A key strength of our study was the use of Youden's index to identify risk thresholds that effectively differentiated high- and average-risk groups based on their positivity rates. Moreover, we used over 10 years of data from the largest sexual health clinic in Victoria, allowing the model training a significant improvement in sample size, thereby improving the model performance. While providing important insights, our study has several limitations. First, as our study population was limited to a single urban sexual health center, additional validation of generalizability is warranted through multisite collaboration and access to more diverse demographic data. Comparing performance on external population samples could illuminate variability in predictive factors and optimal thresholds across settings to further optimize MySTIRisk's screening capabilities. Furthermore, the risk scores represent relative risk within this population in a sexual health clinic rather than absolute risk categories. The optimal cutoff point may vary depending on the setting, such as the general population or clinic settings. Additionally, the cutoff for routine screening may need to be lower to ensure early detection and prevention efforts, requiring the need for adjustment in routine screenings to represent a broader spectrum of risk levels. Second, sexual orientation was defined based on self-reported sexual practices rather than identity, which may have led to misclassification in some cases. Similarly, while relying on self-reported information, we acknowledge inherent limitations such as recall, nonresponse, and social desirability biases. However, CASI represents best practices for minimizing such biases [29]. Third, comparisons of positivity rates between the high/average-risk groups and PrEP/non-PrEP groups represent unadjusted analyses. Given the potential for confounding by differences in demographic and behavioral characteristics, multivariate analysis adjusting for key covariates is warranted in future studies to confirm the findings. However, the significantly higher positivity rates consistently observed in the high-risk groups across infections are notable even without controlling for potential confounders. Fourth, the data sets only included clients from a sexual health center, who can be considered at higher risk than the general population, which includes lower-risk individuals. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings to the general population could be limited. Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate the utility of Youden's index for objectively balancing sensitivity and specificity to inform user-friendly risk assessment tool development. Further external validation of optimized thresholds across diverse populations and settings remains an important area for future research. Similarly, future implementation research should evaluate the impact of providing MySTIRisk risk assessments on testing uptake, treatment adherence, and other outcomes among high-risk groups in real-world settings.

In conclusion, the findings of this study have important implications for policy and practice in sexual health clinics. The alternative way of defining the high-risk population for risk assessment tools for HIV/STIs can guide resource allocation and intervention strategies. Future research should focus on understanding the expenses associated with HIV testing and further refining the risk prediction model to ensure its appropriate use in different settings. It is crucial to remember that the risk tool should be used to identify higher-risk individuals for targeted services, and baseline testing and counseling should be recommended for all individuals, regardless of their risk score.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Monash University for supporting a PhD scholarship for P.L. The authors express gratitude to all who contributed to this study.

Author contributions. L.Z. conceived the study. P.L. conducted data analysis, wrote the initial manuscript draft, and revised the manuscript. N.S. contributed to data analysis. X.X., J.O., E.C., and C.F. contributed to the study design. L.Z. provided supervision and acted as guarantor. All authors provided critical feedback on the manuscript and approved the final version.

Data availability. Data not publicly available.

Financial support. E.P.F.C. is supported by an National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172873). C.K.F. is supported by an NHMRC Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172900). J.O. is supported by the NHMRC investigator grant (GNT1193955).

Contributor Information

Phyu M Latt, Artificial Intelligence and Modelling in Epidemiology Program, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia; Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Nyi N Soe, Artificial Intelligence and Modelling in Epidemiology Program, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia; Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Xianglong Xu, Artificial Intelligence and Modelling in Epidemiology Program, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia; School of Public Health, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Jason J Ong, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia.

Eric P F Chow, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia; Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Christopher K Fairley, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia.

Lei Zhang, Artificial Intelligence and Modelling in Epidemiology Program, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia; Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; Clinical Medical Research Center, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 210008, China.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) fact sheets. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis)/. Accessed 20 August 2023.

- 2. Pande G, Bulage L, Kabwama S, et al. Preference and uptake of different community-based HIV testing service delivery models among female sex workers along Malaba-Kampala highway, Uganda, 2017. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19:799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fairley CK, Chow EP, Hocking JS. Early presentation of symptomatic individuals is critical in controlling sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health 2015; 12:181–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Power M, Dong K, Walsh J, Lewis DA, Richardson D. Barriers to HIV testing in hospital settings within a culturally diverse urban district of Sydney, Australia. Sex Health 2021; 18:340–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blondell SJ, Debattista J, Griffin MP, Durham J. ‘I think they might just go to the doctor’: qualitatively examining the (un)acceptability of newer HIV testing approaches among Vietnamese-born migrants in greater-Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Sex Health 2021; 18:50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Denison HJ, Bromhead C, Grainger R, Dennison EM, Jutel A. Barriers to sexually transmitted infection testing in New Zealand: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017; 41:432–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott H, Vittinghoff E, Irvin R, et al. Development and validation of the personalized sexual health promotion (SexPro) HIV risk prediction model for men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:274–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoenigl M, Weibel N, Mehta SR, et al. Development and validation of the San Diego early test score to predict acute and early HIV infection risk in men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. mysexpro.org. Available at: https://mysexpro.org/en/home/. Accessed 20 August 2023.

- 10. Phyu Mon L, Nyi Nyi S, Fairley C, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of HIV/STI risk communication displays among Melbourne Sexual Health Centre attendees: a cross-sectional, observational, and vignette-based study. Sex Transm Infect. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nieuwenburg SA, Hoornenborg E, Davidovich U, de Vries HJC, Schim van der Loeff M. Developing a symptoms-based risk score for infectious syphilis among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2022; 99:324–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Obuchowski NA, Bullen JA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves: review of methods with applications in diagnostic medicine. Phys Med Biol 2018; 63:07TR01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ying GS, Maguire MG, Glynn RJ, Rosner B. Tutorial on biostatistics: receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for correlated eye data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2022; 29:117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kechagias KS, Kalliala I, Bowden SJ, et al. Role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on HPV infection and recurrence of HPV related disease after local surgical treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022; 378:e070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Amusa L, Zewotir T, North D, Kharsany ABM, Lewis L. Association of medical male circumcision and sexually transmitted infections in a population-based study using targeted maximum likelihood estimation. BMC Public Health 2021; 21:1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen F, Xue Y, Tan M, Chen P. Efficient statistical tests to compare Youden index: accounting for contingency correlation. Stat Med 2015; 34:1560–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu X, Ge Z, Chow EPF, et al. A machine-learning-based risk-prediction tool for HIV and sexually transmitted infections acquisition over the next 12 months. J Clin Med 2022; 11:1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu X, Yu Z, Ge Z, et al. Web-based risk prediction tool for an individual's risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections using machine learning algorithms: development and external validation study. J Med Internet Res 2022; 24:e37850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bao Y, Medland NA, Fairley CK, et al. Predicting the diagnosis of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men using machine learning approaches. J Infect 2021; 82:48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chow EPF, Carlin JB, Read TRH, et al. Factors associated with declining to report the number of sexual partners using computer-assisted self-interviewing: a cross-sectional study among individuals attending a sexual health centre in Melbourne, Australia. Sex Health 2018; 15:350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Phyu Mon L, Nyi Nyi S, Xianglong X, et al. Assessing disparity in the distribution of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in Australia: a retrospective cross-sectional study using Gini coefficients. BMJ Public Health 2023; 1:e000012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Melbourne Sexual Health Centre . MySTIRisk. Available at: https://mystirisk.mshc.org.au/. Accessed 20 August 2023.

- 23. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950; 3:32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J 2005; 47:458–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Traeger MW, Schroeder SE, Wright EJ, et al. Effects of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection on sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:676–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hart TA, Syed WN, Graham WB, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among gay and bisexual men. Sex Transm Infect 2023; 99:167–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Falasinnu T, Gilbert M, Gustafson P, Shoveller J. Deriving and validating a risk estimation tool for screening asymptomatic chlamydia and gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis 2014; 41:706–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vissers DC, Voeten HA, Nagelkerke NJ, Habbema JD, de Vlas SJ. The impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) on HIV epidemics in Africa and India: a simulation study. PLoS One 2008; 3:e2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fairley CK, Sze JK, Vodstrcil LA, Chen MY. Computer-assisted self interviewing in sexual health clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:665–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.