Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Systemic corticosteroids have been shown to improve outcomes in severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia; however, their role in post-COVID-19 persistent lung abnormalities is not well defined. Here, we describe our experience with corticosteroids in patients with persistent lung infiltrates following COVID-19 infection.

RESEARCH QUESTION:

What is the efficacy of systemic corticosteroids in improving lung function and radiological abnormalities in patients following COVID-19 pneumonia?

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS:

This is a single-center retrospective study evaluating patients with persistent respiratory symptoms and abnormal chest computed tomography findings. Patients were divided into two groups based on treatment with corticosteroids: “steroid group” and “nonsteroid group.” Clinical data were collected from the electronic medical records.

RESULTS:

Between March 2020 and December 2021, 227 patients were seen in the post-COVID-19 pulmonary clinic, of which 75 were included in this study. The mean age was 56 years, 63% were female, and 75% were white. The main physiologic deficit was reduced Diffusing capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) at 72% (±22). On chest imaging, the most common findings were ground-glass opacities (91%) and consolidation (29%). Thirty patients received corticosteroid (steroid group) and 45 did not (nonsteroid group). Patients treated with corticosteroids had lower DLCO (DLCO [%]: steroid group 63 ± 17, nonsteroid group 78 ± 23; P = 0.005) and all had ground-glass opacities on imaging compared to 84% in the nonsteroid group (P = 0.04). At follow-up, patients in the steroid group (n = 16) had a significant improvement in spirometry and DLCO. In addition, there was a significant improvement with resolution of ground-glass opacities in both the groups (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

The use of systemic corticosteroids in patients with persistent respiratory symptoms and radiological abnormalities post-COVID-19 was associated with significant improvement in pulmonary function testing and imaging. Prospective studies are needed to confirm whether these findings are the effect of corticosteroid therapy or disease evolution over time.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, coronavirus disease 2019 infection, lung infiltrates, pulmonary function test

In late 2019, a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, emerged in Wuhan, China, and has since spread globally, infecting more than 650 million people.[1,2] The clinical course of infection appears to be extremely variable, from asymptomatic to severe pneumonia with multi-organ failure requiring critical care. At the time of writing, at least 6.7 million people have died following infection, with data on morbidity in survivors still emerging.[2,3] Given the large number of affected patients, understanding the longer-term implications of lung injury, a predominant feature of acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, is critical.[3]

There is evidence that systemic symptoms of COVID-19 infection can persist or develop several months after the infection, leading to the condition known as “post-COVID-19 syndrome.”[4,5,6,7,8,9] The pathophysiology is unknown, although there are different hypotheses, including persistent live virus, autoimmune process, inflammatory sequelae, or dysautonomia.[10,11]

The most common radiological pattern of acute COVID-19 infection is bilateral ground-glass opacification with or without consolidation in a subpleural distribution.[6,12] Radiological findings vary as disease progresses, but persistent computed tomography (CT) imaging abnormalities have been reported up to 180 days postacute COVID-19 infection.[4,13,14] A meta-analysis of over 100 studies found that 55.7% of patients exhibit persistent CT abnormalities 90 days after symptom onset or hospital discharge, with the most common abnormalities being ground-glass opacities or fibrous strip.[15] Radiologically, the pattern is most consistent with organizing pneumonia.[16] Pulmonary function testing (PFT) also shows persistent abnormalities in long COVID patients, with about one-third to one-half of patients having low lung diffusion capacity (DLCO) 3 months after the acute infection.[15,17] Lung pathology in autopsy specimens shows diffuse alveolar damage, and percutaneous lung biopsy in one case report showed type II alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, alveolar septa destruction, extensive lung tissue necrosis, and infiltration of mononuclear cells and lymphocytes.[18,19]

Systemic corticosteroids have been shown to improve clinical outcomes and reduce mortality in hospitalized patients who require supplemental oxygen.[20,21,22] Although the guidelines do not currently support the use of corticosteroids in acute mild-moderate COVID-19 infection, increasing numbers of nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 have been prescribed systemic corticosteroids.[23] Given the number of infected patients, therapies that could potentially prevent permanent fibrosis and functional impairment are critical. We have established a “post-COVID-19 pulmonary clinic” to care for patients with persistent pulmonary symptoms following COVID-19 infection, providing a comprehensive assessment of symptoms, physical examination, and a panel of respiratory testing including chest imaging and PFT. In this study, we assessed the effect of corticosteroids on chest CT and PFT in patients with persistent respiratory symptoms and chest imaging abnormalities following COVID-19 infection.

Methods

Participants and study design

This is a single-center retrospective study. Patients were recruited from the post-COVID-19 pulmonary clinic of a quaternary center where they were evaluated for persistent respiratory complaints following COVID-19 infection. Patients were included in the study if they had persistent radiographic abnormalities on chest CT as reported by a thoracic radiologist and confirmatory COVID-19 testing. Prior chest imaging when available was reviewed to determine the chronicity of lung infiltrates. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study (IRB #21-652), and patient consent was waived as data were collected through chart review.

Data collection

Clinical data on demographics, comorbidities, chest CT, PFT, COVID-19-specific therapies (including dose of steroids), hospitalization, and outcomes were extracted from the electronic medical record. Comorbidities included in the search were obesity (body mass index ≥30), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, interstitial lung disease (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, nonspecific interstitial pneumonias, connective tissue-related interstitial lung disease, and other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias), history of any transplantation, pulmonary hypertension, systolic and diastolic heart failure, coronary artery disease (CAD), history of pulmonary embolism, rheumatologic disease, or malignancy. To maintain data consistency and integrity, binary radiological data were collected indicating the presence or absence of parenchymal abnormalities.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using JMP 16.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Qualitative variables were described using frequencies and percentages, and quantitative variables by means and standard deviation. Normality for continuous variables was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. A mean comparison was carried out using the Student’s t-test in the presence of normality, and if otherwise, using the Wilcoxon test. For qualitative variables, a comparison of percentages between the groups was carried out using Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables or Chi-square test for contingency tables with more than two categories. For quantitative measures, changes from baseline between the groups were compared using matched pairs t-tests. Significance was accepted at a level of P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

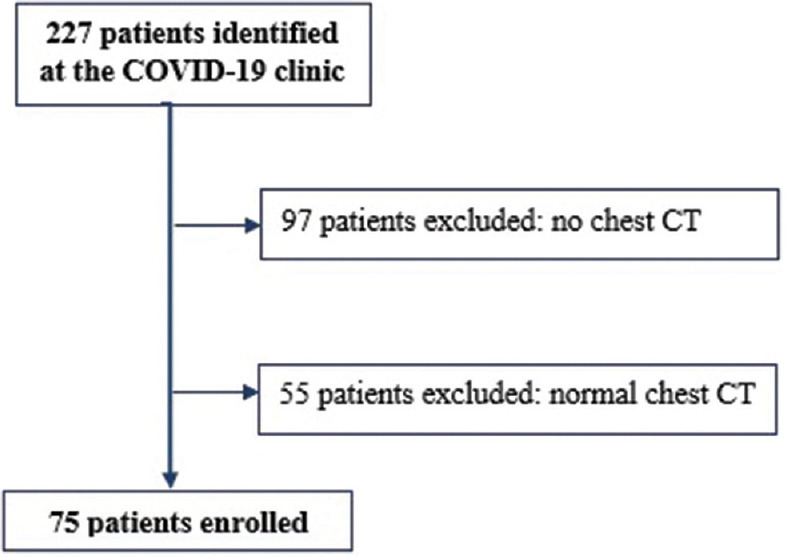

Between March 2020 and December 2021, 227 patients with COVID-19 infection were referred to the post-COVID-19 pulmonary clinic. One hundred and fifty-two patients did not have an abnormal chest CT scan and were excluded from the study. The final sample size for the study was 75 patients [Figure 1]. The mean age of participants was 56 (±12) years, with 63% of women and 75% of white. Asthma was the most common comorbidity (21%), with other comorbidities including COPD, CAD, interstitial lung disease, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, history of malignancy, solid organ transplantation, pulmonary embolism, and rheumatologic diseases. Thirty-eight percent of participants were ex-smokers and one was still actively smoking. Seventy-three percent were hospitalized with only one patient admitted to the intensive care unit. Dexamethasone, remdesivir, and tocilizumab were the three medications approved for the treatment of COVID-19 infections during the study timeline. Forty-nine patients (65%) received dexamethasone, 40 patients (53%) received remdesivir, and 7 patients (9%) received tocilizumab. Patients were seen in the clinic an average of 121 days after their acute infection. After their initial assessment in the outpatient clinic, 40% of patients were placed on systemic corticosteroid treatment, with prednisone being the most commonly used oral corticosteroid at a starting dose ranging from 20 to 80 mg/day followed by a taper over on average 57 days. To evaluate the effects of corticosteroid therapy, patients were divided into two groups: “steroid group” (n = 30) and “nonsteroid group” (n = 45). Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups, and there were no significant differences in hospital COVID-19-specific therapies between the two groups [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria. CT = Computed tomography, COVID-19 = Coronavirus disease 2019

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all participants by treatment group*

| Characteristics | Overall (n=75), n (%) | Steroid group (n=30), n (%) | Nonsteroid group (n=45), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 56±12 | 56±12 | 57±13 | 0.2 |

| Sex (male/female) | 28/47 | 10/20 | 18/27 | 0.6 |

| Race (white/black/Asian)† | 56/18/1 | 21/8/1 | 34/10/0 | 0.5 |

| Smoking history (yes/no) | 28/46 | 9/20 | 19/26 | 0.5 |

| Current smoker (yes/no) | 1/74 | 0/30 | 1/44 | 1.0 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| COPD | 5 (7) | 1 (3) | 4 (9) | 0.6 |

| Asthma | 16 (21) | 8 (27) | 8 (18) | 0.4 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 1.0 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1.0 |

| Heart failure | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0.5 |

| CADs | 5 (7) | 0 | 5 (11) | 0.08 |

| History of pulmonary embolism | 9 (12) | 2 (7) | 6 (13) | 0.5 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 9 (12) | 6 (17) | 6 (13) | 0.7 |

| History of any malignancy | 6 (8) | 5 (17) | 1 (2) | 0.03 |

| History of any transplantation | 3 (4) | 2 (7) | 1 (2) | 0.6 |

| Medications used for acute COVID-19 | ||||

| Dexamethasone | 49 (65) | 18 (60) | 31 (69) | 0.5 |

| Remdesivir | 40 (53) | 16 (53) | 24 (53) | 1.0 |

| Tocilizumab | 7 (9) | 1 (3) | 6 (13) | 0.2 |

| CT findings | ||||

| Ground-glass opacities | 67 (91) | 30 (100) | 37 (84) | 0.04 |

| Consolidations | 22 (29) | 10 (35) | 12 (40) | 0.1 |

| Reticulations | 17 (23) | 8 (27) | 9 (20) | 0.6 |

| Fibrosis | 4 (5) | 1 (3) | 3 (7) | 0.6 |

*Plus-minus values are means±SD, †Race or ethnic group was recorded in the patient’s electric health record. SD=Standard deviation, CT=Computed tomography, COVID-19=Coronavirus disease 2019, COPD=Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CADs=Coronary artery diseases

Pulmonary function tests at baseline and follow-up

Of the 75 patients, 69 had spirometry at the initial visit and 22 had follow-up spirometry. The time between the two tests ranged from 2 to 10 months. At initial visit, mean forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (%) and forced vital capacity (FVC) (%) as well as FEV1/FVC ratio were above 80; however, DLCO was slightly reduced at 72% (±22). Only 51 patients had lung volumes measured at the initial visit. Of those, the mean total lung capacity (TLC) was slightly low (79% predicted). For the 22 patients with baseline and follow-up PFT, there was a significant improvement in FEV1 and FVC on follow-up (FEV1 [L]: baseline 2.51 ± 0.69, follow-up 2.67 ± 0.84; P = 0.004 and FVC (L): baseline 3.16 ± 0.89, follow-up 3.32 ± 1.09; P = 0.004). Similarly, in the subgroup with follow-up lung volumes and DLCO, both TLC and DLCO improved significantly (TLC [L]: baseline 3.78 ± 0.91, follow-up 4.12 ± 1.02; P = 0.04 and DLCO [mL/min/mmHg]: baseline 14.74 ± 4.91, follow-up 18.21 ± 7.05; P = 0.01).

Changes in pulmonary function tests in the steroid and nonsteroid groups

Baseline characteristics were similar between the steroid and nonsteroid groups. FEV1 and FVC were marginally lower in the steroid group compared to the nonsteroid group (FEV1 [L]: steroid group 2.33 ± 0.67, nonsteroid group 2.64 ± 0.70; P = 0.07 and FVC [L]: steroid group 2.93 ± 0.82, nonsteroid group 3.33 ± 0.91; P = 0.07) [Table 2]. In addition, there was a significant difference in DLCO (DLCO [mL/min/mmHg]: steroid group 15.04 ± 4.35, nonsteroid group 19.63 ± 6.85; P = 0.002 and DLCO [%]: steroid group 63 ± 17, nonsteroid group 78 ± 23; P = 0.005). Lung volumes were not different between the two groups. On follow-up visit, there were no differences in PFT between the two groups (n = 16 in the steroid group and n = 6 in the nonsteroid group] [Table 2]. For the patients who had follow-up spirometry, there was a significant improvement in the steroid group(FEV1 (L): baseline 2.33 ± 0.67, follow-up 2.66 ± 0.90; P = 0.008, FVC [L]: baseline 2.93 ± 0.82, follow-up 3.28 ± 1.11; P = 0.007, FVC [%]: baseline 82 ± 22, follow-up 85 ± 23; P = 0.0008. In a small subset of patients who had follow-up DLCO (n = 12), there was a significant improvement in DLCO (DLCO [mL/min/mmHg]: baseline 14.63 ± 5.50, follow-up 18.09 ± 7.31; P = 0.07 and DLCO [%]: baseline 56 ± 17, follow-up 64 ± 18; P = 0.04). In the nonsteroid group, only six patients had follow-up PFT and the changes compared to baseline were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline and follow-up spirometry in the steroid and nonsteroid groups

| PFT | Steroid | Nonsteroid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Baseline (n=69) | Follow-up (n=16) | Matched t-test (P) | Baseline (n=40) | Follow-up (n=6) | Matched t-test (P) | |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.33±0.67 | 2.66±0.90 | 0.008 | 2.64±0.70 | 2.72±0.73 | 0.3 |

| FEV1% | 86±30 | 86±20 | 0.7 | 90±16 | 90±9 | 0.2 |

| FVC (L) | 2.93±0.82 | 3.28±1.11 | 0.007 | 3.33±0.91 | 3.45±1.11 | 0.3 |

| FVC % | 82±22 | 85±23 | 0.0008 | 90±18 | 89±13 | 0.2 |

| FEV1/FVC | 80±5 | 82±8 | 0.6 | 80±6 | 80±6 | 0.5 |

Data are shown as mean±SD. FEV1=Forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC=Forced vital capacity, FEV1/FVC=Ratio of FEV1 and FVC, SD=Standard deviation, PFT=Pulmonary function testing

Chest computed tomography findings at baseline and on follow-up

Of the 75 participants, 45 (60%) had follow-up chest CT. Scans were reviewed by a thoracic radiologist and an attending pulmonologist. Initial chest scans were obtained ~2 months from the time of acute illness (positive COVID-19 test). The most frequent findings on chest CT were ground-glass opacities (91%), consolidations (29%), and reticulations (23%) [Table 1]. All patients treated with corticosteroids had ground-glass opacities on chest imaging compared to 84% of patients in the nonsteroid group (Fisher’s exact test = 0.04). There were no other differences in chest CT findings between the two groups at the time of initial evaluation (all P > 0.1). The time interval for follow-up chest CT scans was an average 6 months from the time of COVID-19 infection. On follow-up imaging, 62% of patients had persistent ground-glass opacities, 11% had consolidations, and 29% had reticular changes. Seventy-nine percent of patients in the steroid group had ground-glass opacities on follow-up scans compared to 43% in the nonsteroid group (Fisher’s exact test = 0.02). When compared to baseline imaging, there was a significant improvement in ground-glass opacities on follow-up in both the steroid and nonsteroid groups (Fisher’s exact test < 0.05 for both the groups).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe the physiological and radiological abnormalities in patients with persistent respiratory symptoms and abnormal chest CT following COVID-19 infection, and investigate the role of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of this patient population. The most frequent radiological abnormality observed on chest imaging in our cohort was ground-glass opacities, while the primary physiological abnormality was a decreased DLCO. After the initial clinic evaluation, 40% of patients were treated with corticosteroid which resulted in improved PFT and imaging on follow-up. In addition to imaging abnormalities, patients who received corticosteroids had lower DLCO values at baseline compared to those who did not receive corticosteroids highlighting that corticosteroid treatment was based on physiological deficits rather than imaging abnormalities and symptomatology alone.

Studies evaluating PFT in post-COVID-19 patients have shown inconsistent results, in part due to differences in timing and severity of the disease. Fumagalli et al. evaluated the respiratory function of survivors of COVID-19 pneumonia both at the time of clinical recovery and 6 weeks postdischarge.[24] FEV1 and FVC were reduced at the time of initial assessment and improved on follow-up, although FVC remained reduced, suggesting persistent restrictive disease at 6 weeks postdischarge.[24] Another study followed patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia and measured PFT serially starting before hospital discharge, then at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after discharge.[25] Baseline PFT showed reduced FVC and FEV1 which improved over time, particularly at 6- and 12-month follow-up.[25] Notably, DLCO was not measured in either of these studies. On the other hand, Huang et al. assessed DLCO in early convalescence phase (30 days postdischarge) and found a reduced DLCO in more than half of the COVID-19 patients.[26] Patients with severe illness had a higher incidence of DLCO impairment compared to mild and moderate cases.[26] Similarly, Zhang et al. showed reduced DLCO in 48% of patients with severe COVID-19 up to 8 months after discharge.[27] A prospective observational Swiss COVID-19 study found that DLCO measured at 4 months is the most important physiologic deficit in patients who had severe/critical respiratory COVID-19.[28] In our cohort of patients who had mild-to-moderate COVID-19 pneumonia, we observed a reduced DLCO in 53% of patients at their initial clinic visit.

In addition to persistent physiologic abnormalities, some patients following COVID-19 infection have persistent chest imaging abnormalities.[29] The radiological findings of acute COVID-19 pneumonia are characteristic and distinct from other viral infections, presenting with progressive ground-glass opacities and alveolar consolidations with subpleural and basilar location, rounded lesions, crazy-paving pattern, linear densities, parenchymal bands, and architectural distortions.[6,12,28,29,30] While the trajectory of radiological patterns is heterogeneous, most cases show improvement, while others may exhibit signs of pulmonary fibrosis even before hospital discharge.[27,31] The most common radiologic finding in our cohort was ground-glass opacities in 91% of patients. The similarity between post-COVID-19 organizing pneumonia-like presentation and postinfection organizing pneumonia is the basis for the use of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of post-COVID-19 organizing pneumonia.[32,33,34,35] Several case reports have described improvement in chest imaging and PFT, as well as the relief of concomitant symptoms in patients following COVID-19 with systemic corticosteroid treatment.[36,37,38,39,40,41] In our cohort, patients treated with corticosteroids had marked improvement in PFT, while the group that did not receive corticosteroids did not show significant changes in PFT. However, the lack of statistical significance in the latter group can be explained by the smaller number of patients who had follow-up PFT. Persistent functional deficits, even in a relatively small proportion of infected patients, may represent a significant disease burden, and prompt therapy may avoid potentially permanent fibrosis and functional impairment. Nonetheless, guidelines on the use of corticosteroids in post-COVID-19 patients are not available and physicians have not been provided a clear roadmap for the pharmacological management in these population.[20,21,22] In a prospective cohort study, Myall et al. followed patients with COVID-19 infection using a structured protocol to screen for sequelae of COVID-19 pneumonia. Patients were assessed by telephone 4 weeks after discharge and patients with persistent symptoms were scheduled for an outpatient assessment at 6 weeks. After the initial visit, patients with persistent radiological interstitial lung changes were reviewed in the interstitial lung disease meeting and offered treatment with corticosteroids. The authors showed that early treatment with corticosteroids was well tolerated and associated with rapid and significant improvement in symptoms, PFT, and imaging.[42]

There are several limitations to our study. First, retrospective analyses come with inherent limitations, including the potential for misclassification bias, unaccounted-for confounding factors, and constraints related to the planned approach and patient follow-up. The sample size of the study was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Only a small number of patients in the nonsteroid group had follow-up spirometry limiting the ability to draw definite conclusions on the effects of corticosteroids and the natural improvement in PFT without treatment. Furthermore, radiological data collection was binary, specifying the presence or absence of parenchymal abnormalities and infiltrates, with no information regarding the severity of the findings. This limitation restricted our ability to quantify the degree of improvement without complete resolution.

The use of corticosteroids in patients with persistent respiratory symptoms and chest CT abnormalities following COVID-19 infection was associated with significant improvement in PFT and imaging. Randomized placebo-controlled studies are needed to confidently conclude whether the radiological or physiological abnormalities would have normalized spontaneously over a longer period of time and whether treatment with corticosteroids prevents progression to fibrotic lung disease. The findings should help inform future studies on the use of corticosteroids in this patient population.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bogoch II, Watts A, Thomas-Bachli A, Huber C, Kraemer MU, Khan K. Pneumonia of unknown aetiology in Wuhan, China: Potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa008. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard |WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. [[Last accessed on 2022 Jul 11]]. Available from: https://www.covid19.who.int/

- 3.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York city area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yong SJ. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: Putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis (Lond) 2021;53:737–54. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1924397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: A multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:1072–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Borst B, Peters JB, Brink M, Schoon Y, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Schers H, et al. Comprehensive health assessment 3 months after recovery from acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e1089–98. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort:7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cares-Marambio K, Montenegro-Jiménez Y, Torres-Castro R, Vera--Uribe R, Torralba Y, Alsina--Restoy X, et al. Prevalence of potential respiratory symptoms in survivors of hospital admission after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chron Respir Dis. 2021;18:14799731211002240. doi: 10.1177/14799731211002240. doi:10.1177/14799731211002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confronting the Pathophysiology of Long COVID –The BMJ. [[Last accessed on 2022 Jul 11]]. Available from: https://www.blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/12/09/confronting-the-pathophysiology-of-long-covid/

- 11.Fogarty H, Townsend L, Ni Cheallaigh C, Bergin C, Martin-Loeches I, Browne P, et al. COVID19 coagulopathy in Caucasian patients. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:1044–9. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley BT, Maioli H, Johnston R, Chaudhry I, Fink SL, Xu H, et al. Histopathology and ultrastructural findings of fatal COVID-19 infections in Washington state: A case series. Lancet. 2020;396:320–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Gui S, Liang B, Li L, et al. Time course of lung changes at chest CT during recovery from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Radiology. 2020;295:715–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Dong C, Hu Y, Li C, Ren Q, Zhang X, et al. Temporal changes of CT findings in 90 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: A longitudinal study. Radiology. 2020;296:E55–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.So M, Kabata H, Fukunaga K, Takagi H, Kuno T. Radiological and functional lung sequelae of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21:97. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01463-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martini K, Larici AR, Revel MP, Ghaye B, Sverzellati N, Parkar AP, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia imaging follow-up: When and how?A proposition from ESTI and ESR. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:2639–49. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Froidure A, Mahsouli A, Liistro G, De Greef J, Belkhir L, Gérard L, et al. Integrative respiratory follow-up of severe COVID-19 reveals common functional and lung imaging sequelae. Respir Med. 2021;181:106383. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beigmohammadi MT, Jahanbin B, Safaei M, Amoozadeh L, Khoshavi M, Mehrtash V, et al. Pathological findings of postmortem biopsies from lung, heart, and liver of 7 deceased COVID-19 patients. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29:135–45. doi: 10.1177/1066896920935195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J, Yu J, Zhou S, Zhang J, Xu J, Niu C, et al. What can we learn from a COVID-19 lung biopsy? Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:410–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Yan B, Gao R, Ren J, Yang J. Effectiveness of corticosteroids to treat severe COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;100:108121. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Sterne JA, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically Ill patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley MC, Perez-Vilar S, Chillarige Y, Dong D, Martinez AI, Weckstein AR, et al. Systemic corticosteroid use for COVID-19 in US outpatient settings from April 2020 to August 2021. JAMA. 2022;327:2015–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fumagalli A, Misuraca C, Bianchi A, Borsa N, Limonta S, Maggiolini S, et al. Pulmonary function in patients surviving to COVID-19 pneumonia. Infection. 2021;49:153–7. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01474-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fumagalli A, Misuraca C, Bianchi A, Borsa N, Limonta S, Maggiolini S, et al. Long-term changes in pulmonary function among patients surviving to COVID-19 pneumonia. Infection. 2022;50:1019–22. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01718-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Tan C, Wu J, Chen M, Wang Z, Luo L, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on pulmonary function in early convalescence phase. Respir Res. 2020;21:163. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01429-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang S, Bai W, Yue J, Qin L, Zhang C, Xu S, et al. Eight months follow-up study on pulmonary function, lung radiographic, and related physiological characteristics in COVID-19 survivors. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13854. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93191-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guler SA, Ebner L, Aubry-Beigelman C, Bridevaux PO, Brutsche M, Clarenbach C, et al. Pulmonary function and radiological features 4 months after COVID-19:first results from the national prospective observational Swiss COVID-19 lung study. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2003690. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03690-2020. Published 2021 Apr 29. doi:10.1183/13993003.03690-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Z, Guo D, Li C, Fang Z, Chen L, Yang R, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019: Initial chest CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:4398–406. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06816-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raoof S, Amchentsev A, Vlahos I, Goud A, Naidich DP. Pictorial essay: Multinodular disease: A high-resolution CT scan diagnostic algorithm. Chest. 2006;129:805–15. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui N, Zou X, Xu L. Preliminary CT findings of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Imaging. 2020;65:124–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radzikowska E, Wiatr E, Langfort R, Bestry I, Skoczylas A, Szczepulska-Wójcik E, et al. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia-results of treatment with clarithromycin versus corticosteroids-Observational study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazdyrev E, Panova M, Zherebtsova V, Burdenkova A, Grishagin I, Novikov F, et al. The hidden pandemic of COVID-19-induced organizing pneumonia. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022;15:1574. doi: 10.3390/ph15121574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gudmundsson G, Sveinsson O, Isaksson HJ, Jonsson S, Frodadottir H, Aspelund T. Epidemiology of organising pneumonia in Iceland. Thorax. 2006;61:805–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.059469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drakopanagiotakis F, Paschalaki K, Abu-Hijleh M, Aswad B, Karagianidis N, Kastanakis E, et al. Cryptogenic and secondary organizing pneumonia: Clinical presentation, radiographic findings, treatment response, and prognosis. Chest. 2011;139:893–900. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siafarikas C, Stafylidis C, Tentolouris A, Samara S, Eliadi I, Makrodimitri S, et al. Radiologically suspected COVID-19-associated organizing pneumonia responding well to corticosteroids: A report of two cases and a review of the literature. Exp Ther Med. 2022;24:453. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simões JP, Alves Ferreira AR, Almeida PM, Trigueiros F, Braz A, Inácio JR, et al. Organizing pneumonia and COVID-19: A report of two cases. Respir Med Case Rep. 2021;32:101359. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2021.101359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horii H, Kamada K, Nakakubo S, Yamashita Y, Nakamura J, Nasuhara Y, et al. Rapidly progressive organizing pneumonia associated with COVID-19. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;31:101295. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim T, Son E, Jeon D, Lee SJ, Lim S, Cho WH. Effectiveness of steroid treatment for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia-like reaction: A case report. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;16:491–4. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golbets E, Kaplan A, Shafat T, Yagel Y, Jotkowitz A, Awesat J, et al. Secondary organizing pneumonia after recovery of mild COVID-19 infection. J Med Virol. 2022;94:417–23. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alsulami F, Dhaliwal I, Mrkobrada M, Nicholson M. Post COVID-19 organizing pneumonia: Case series for 6 patients with post-COVID interstitial lung disease. [[Last accessed on 2022 Dec 30]];Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2021 8:108–11. Available from: https://www.medcraveonline.com/JLPRR/JLPRR-08-00261.php . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myall KJ, Mukherjee B, Castanheira AM, Lam JL, Benedetti G, Mak SM, et al. Persistent post-COVID-19 interstitial lung disease. An observational study of corticosteroid treatment. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:799–806. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-1002OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]