INTRODUCTION

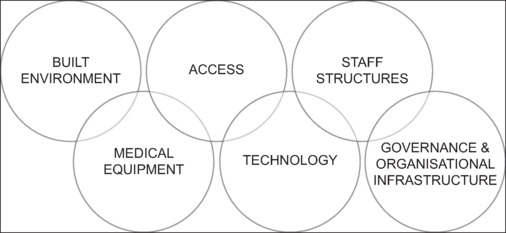

The mental health human resource forms the basic component of mental health service delivery in any sector. Mental health and well-being can be promoted by various ways, among which focus on human resources is of utmost importance. Mental health infrastructure can be conceptualized as the basic facilities which involve public works, underlying foundations, and the network system needed to provide goods and services.[1] Infrastructure related to health encompasses a range of establishments needed to provide health care, like hospitals, other health establishments, non-governmental organizations, and a service delivery system which runs integrated with these facilities. The various components of health infrastructure are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Various components of health infrastructure

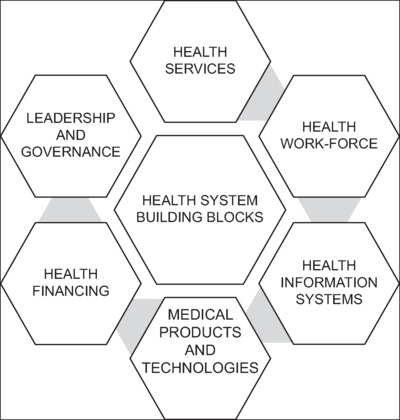

As per World Health Organization (WHO), health system building blocks comprise six sectors as described in Figure 2.[2,3] An effective mental health system focuses on providing mental health services to all in need in the most effective manner, distributed equitably and which promotes human rights and health outcomes. It should integrate mental health services into primary health care and link it to secondary care.[4,5] We focus our discussion on the mental health work force and service delivery.

Figure 2.

Health system infrastructure and its building blocks

Existing mental health infrastructure in India with focus on human resources

National Mental Health Survey 2015–16 (NMHS)[6] reflects that the mental health services in India are ‘far from satisfactory’. Despite a sustained focus in improving mental health systems, the translated changes appear very few. The treatment gap for mental health remains huge. The treatment gap in India is around 80%, and the disability associated with mental, neurological, and substance use disorders (MNSuDs) was around 0.7% to 28.2%. The NMHS data on the existing infrastructure are indeed grave in India. Table 1 gives a snapshot of the infrastructure state-wise.

Table 1.

Findings of NMHS showing a snapshot of infrastructure related to mental health

| Coverage of DMHP | ||

| Districts covered by DMHP (%) | 14.29% (Assam)- 100% (Kerala) | |

| Population covered by DMHP (%) | 14.20% (Madhya Pradesh)- 100% (Kerala) | |

| Tribal population covered by DMHP (%) | 3.99% (Uttar Pradesh)- 100% (Kerala) | |

| Mental Health Care Facilities | ||

| Mental hospitals | 0 (Manipur)- 6 (Gujarat and West Bengal) | |

| Medical colleges with psychiatry department | 1 (Jharkhand)-28 (Uttar Pradesh) | |

| General hospitals with psychiatry units | 2 (Jharkhand)- 29 (Punjab) | |

| Mobile mental health units | Available only in Gujarat (4), Kerala (22), and Tamil Nadu (432) | |

| Day care Centers | 2 (Madhya Pradesh)- 137 (Tamil Nadu) | |

| De-addiction units/Centers | 2 (Jharkhand)- 120 (Tamil Nadu) | |

| Residential half-way homes | 1 (Assam and Jharkhand) – 43 (Tamil Nadu) | |

| Long stay homes | 1 (Gujarat)-146 (Kerala) | |

| Hostel (quarter stay homes) | Only in Gujarat and Manipur (1) | |

| Vocational Training centers | 1 (Rajasthan)- 26 (Chattisgarh) | |

| Sheltered workshops | 2 (Jharkhand)-6 (Kerala) | |

| Mental Health Human Resources (per 100000 population) | ||

| Psychiatrists | 0.05 (Madhya Pradesh)-1.20 (Kerala) | |

| Medical doctors trained in mental health | 0.05 (Madhya Pradesh)- 9.73 (Manipur) | |

| Clinical psychologists | 0.01 (Rajasthan)-0.09 (Tamil Nadu) | |

| Nurses trained in mental health | 0.01 (Punjab and Rajasthan) – 10.47 (Tamil Nadu) | |

| Nurses with DPN qualification | <0.01 (Uttar Pradesh)-0.21 (Manipur) | |

| Psychiatric Social workers | 0.01 (Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan)- 0.67 (Manipur) | |

| Rehabilitation workers and Special education teachers | 0.05 (Jharkhand)-10.26 (Kerala) | |

| Professional and Paraprofessional psychosocial counselors |

0.12 (Jharkhand)- 61.42 (Manipur) |

|

|

Mental health sciences training

| ||

|

Curriculum

|

No. of Institutions

|

Intake per year

|

| MD Psychiatry | 0 (CT)-19 (TN) | 3 (MN)-52 (TN) |

| Diploma in Psychological medicine (DPM) | 0 in most states 1 (WB)-5 (KL) | 2 (UP)- 19 (JH) |

| M.Sc. Psychiatric Nursing | 1 (JH)-37 (TN &KL) | 3 (JH)- 164 (KL) |

| M.Phil. Clinical Psychology | 0 (PB)-6 (UP) | - |

| Social work | 1 (PB)-23 (TN) | |

| M.Phil. (Psychiatric social work) | 3 (TN) | |

| Health Education Activities in Mental Health (percentage of districts where IEC activities were carried out) | ||

| >50% of the districts | Kerala and Gujarat | |

| <50% of the districts | Tamil Nadu, Assam, Manipur, and Punjab | |

| Limited IEC activities | Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh | |

| No activities | Chattisgarh | |

| Civil society organization (s) in mental health | Mental Health NGOs functioning in all states except Jharkhand | |

As per Mental Health Atlas 2020, the existing infrastructure and mental health systems in the South East Asian region and low- and middle-income countries are depicted in Table 2, and information available from India in Mental Health Atlas 2017 has also been provided.[7]

Table 2.

Findings from Mental Health Atlas 2020 (for SEAR and LMIC) and 2017 (India)

| MENTAL HEALTH PARAMETER (per 100 000 population) | SOUTHEAST ASIAN REGION (SEAR) | LOWER-MIDDLE- INCOME COUNTRIES (LMICs) | INDIA 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median numbers of outpatient facilities and visits | Facilities-0.21 | 0.18 | Total 952 |

| Visits- 277.4 | 475.5 | 369.0 | |

| Community-based/non-hospital mental health outpatient facility- 1217 total, visits-11.1 Other outpatient facilities (e.g., mental health day care or treatment facility)-240 total, visits -1.82 Outpatient facilities specifically for children and adolescents (including services for developmental disorders)-139, visits-5.01 Other outpatient services for children and adolescents (e.g., day care)- total 67, visits-0.33 |

|||

| Median percentage of visits to outpatient services, by sex | Female -47% | Female -46% | - |

| Male -53% | Male -54% | - | |

| Median number of mental hospital facilities, beds, and admissions | Facilities -0.01 | Facilities -0.02 | Total 136 mental hospitals |

| Beds -3.6 | Beds -3.8 | Beds -1.43 | |

| Admissions -34.5 | Admissions -34.5 | 6.95 | |

| Median numbers of psychiatric units in general hospital facilities, beds, and admissions | Facilities -0.13 | Facilities -0.06 | Total 389 GHPU |

| Beds -1.3 | Beds -0.8 | Beds -0.56 | |

| Admissions -30.1 | Admissions -7.1 | Admissions -4.38 | |

| Median rate of total inpatient care | Facilities -0.16 | Facilities -0.09 | Not reported |

| Beds -3.0 | Beds -4.4 | ||

| Admissions -76.3 | Admissions -59.8 | ||

| Resources for mental health | |||

| Median number of mental health workers | 2.8 | 3.8 | 1.93 |

| Psychiatrists -0.4 | Psychiatrists -0.4 | Psychiatrists -0.29 | |

| Mental Health Nurses-0.9 |

Mental Health Nurses-1.3 |

Mental Health Nurses-0.80 Child psychiatrists- 0.0 |

|

| Psychologists -0.3 | Psychologists -0.3 | Psychologists -0.07 | |

| Social workers-0.1 | Social workers-0.2 | Social workers-0.06 | |

| Other specialized mental health workers-0.4 | Other specialized mental health workers-0.1 | Occupational therapists- 0.03 Speech therapists- 0.17 Other paid mental health workers- 0.36 |

|

Developing infrastructure

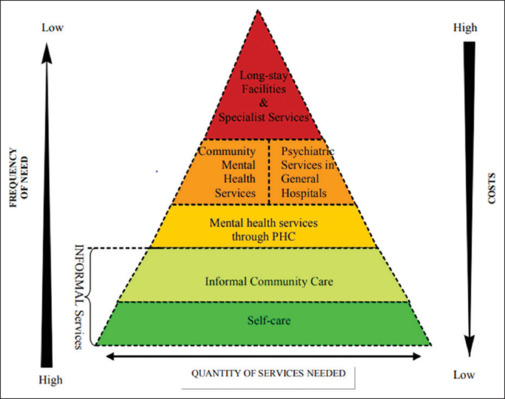

WHO has formulated a service delivery framework to help countries plan in the organization of mental health services. Figure 3 is taken from WHO Mental Health Policy, Planning and Service development, which depicts the pyramid model.[8] It is interesting to note that the service of mental hospitals or GHPU involves a high cost and is less frequently needed but still remains the most commonly provided mental health service. Thus, there is a dire need of integration with primary health care, informal community care, and promotion of self-help, which involves low cost and is more in need.

Figure 3.

Adopted from WHO showing the pyramid model for mental health service delivery

Self-care

Promoting self-care can be one of the most cost-effective strategies in building mental well-being infrastructure. It involves people taking care of their mental health needs with help from available social support like friends and families. Self-care includes the ability to manage stress, increase resilience, discuss and mitigate emotional problems, and also have the knowledge of asking help when needed and sources from where it can be sought. The main infrastructure development in this arena lies in creating awareness about various modes of self-care for mental health, providing information to people via various sources and channeling communication regarding the same (IEC activities). Mental health literacy should be promoted by initiatives of both governmental and non-governmental sectors in a manner that it is available and accessible. Various strategies which can be implemented accordingly are described subsequently in Table 3.

Table 3.

Various self-care strategies, identification of problem areas, scope of infrastructure development, and possible specific actions for promotion of mental health

| Self-care strategies | Identification of problem areas | Scope of Infrastructure development | Specific actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit contact with ‘high risk’ situations likely to negatively affect mental health | Substance use | IEC activities regarding harmful aspects of substance use and possible risk of exposure to other high-risk situations arising out of substance use like ‘drink and drive’. |

|

| Unsafe sexual practices/sexual risk taking | Sexuality education to be followed in school programs. |

|

|

| Avoiding violent situations | Education about possible violent situations like road rage and mob violence. |

|

|

| Develop skills to manage stress | Childhood and adolescent stress | IEC activities about promotion of mental health and ways of stress mitigation in children and adolescents. Avoid smoking and alcohol. Biological cycles to be made regular. Mitigating occupational hazards |

|

| Workplace-related stress | Focus on the formation of psychological first-aid groups in work places who can serve as points of contact for mitigating workplace stress. |

|

|

| Any other stress | IEC activities on various modalities of stress management and relaxation techniques. |

|

|

| Ability to discuss and manage emotional problems as they arise. | Not able to acknowledge and identify emotional problems. | IEC on common emotional problems for easy identification. Nationwide digital platform for discussing emotional problems. |

|

| Know when to seek help and who to seek help from | Having low/no knowledge of existing mental health services. | IEC activities in community places sharing information about availability of various levels of mental health care and how each of them can be accessed. |

|

Recommendations for development of self-care strategies

Informal community care

This involves services available in community but not a direct part of the ‘formal’ health system. Services at this level include traditional healers, professionals who are in other sectors like education (teachers), a legal framework (police), village health workers, an informal family, and social associations. Various non-governmental organizations working in various sectors other than health can also provide help in promotion of mental well-being of the community. This layer of the service delivery pyramid acts as a mid-way and helps in effectively caring for a bigger population and thus decreases the need of moving into the next level of the pyramid. They also form a bridge for ‘down-referral’ as patients already treated for mental disorders and on treatment and maintaining well can be collaborated with such services to ensure compliance and prevent relapse. The advantage lies in that these systems are usually accessible and easily acceptable by the community as it is an integral part of it. The disadvantages are that the service quality is highly variable and there remain chances of human rights violation. So, they should not be in the ‘core’ of mental health services but should function as a useful complement to formal services and can work in alliance with them.

Recommendations on development of informal community care

Incorporation of traditional healers in main stream mental health like the Dawa-Dua program.

Training of teachers, police personnels, and other various machinery of public welfare in basics of mental health as they are in a touch with the huge general population.

Non-governmental organizations serving in health sectors other than mental health to incorporate mental health in all its aspects.

Usage of various settings like community meeting places – Gram panchayat or village Anganwadi centers, display of posters at such places, and screening audio-visual interventions/films in village gatherings (as done in PRIME – Program for Improving MEntal health care – mental health care plan done in five countries including India – Sehore district of Madhya Pradesh).

Extension of programs already running in some parts of the country to other parts like MINDS Community Mental Health Worker Program where lay persons from the community are trained for screening at the community level and providing basic mental health first aid.

ATMIYATA Project – implemented in the rural area of Maharashtra; it involves a two-tier community-led mental health initiative. The tier consists of “Atmiyata Mitras” belonging to various caste- and religion-based sectors of the village and trained to identify individuals in mental distress. The second tier consisted of “Atmiyata Champions”, who are important members of the community (community leaders, former teachers, etc.) and are well known and easily approachable in the village. They are trained to identify individuals in mental distress and provide structured counseling. It utilizes digital tools like low-cost mobile phones and Atmiyata app (has two versions – one for champions and the other for the general public). Programs on the same model can be implemented on a wider scale in low-resource settings to address the burden of Common Mental Disorders.

The Chiri (Smile) program was launched by Kerala Government as a part of the “Our Responsibility to Children” program. It is a community intervention connecting people with an age group of 12–18 years. It was run by the volunteer student police cadets who identified children who need mental health support, directed them to community health workers, and eventually connected them and their parents to mental health experts.

Models like this show that the involvement of informal services into the mental health arena not only improves the outcome but also ensures their acceptability.

Integrating mental health services into primary health care

This level in the pyramid is one of the most crucial points of mental health service delivery in India. In India, the various policies and programs of the Government focus on this aspect. The National Mental Health Program (NMHP) and District Mental Health Program (DMHP) form the backbone of delivery of mental health services in India.

Recommendations for integration in accordance with operational guidelines of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is described in Table 4[9]

Table 4.

Service delivery model for integrating mental health into primary health as per operational guidelines of Ayushman Bharat

| INDIVIDUAL/FAMILY/COMMUNITY LEVEL | HEALTH AND WELLNESS CENTER–SUB-HEALTH CENTER LEVEL (HWC) | PRIMARY HEALTH CENTER/URBAN PHC (PHC/UPHC) | HIGHER LEVELS OF CARE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUMAN RESOURCE | ASHA/ASHA Facilitators, Multi-purpose Workers (MPW -F/M, Community Health Workers (CHW) | Community Health Officers (CHO) | MEDICAL OFFICERS (MO) | SPECIALISTS |

| SERVICE DELIVERY | AWARENESS

CASE DETECTION

PSYCHOSOCIAL COMPETENCIES TO BE IMPROVED

FOLLOW-UP IN COMMUNITY

|

AWARENESS

PROMOTION OF MENTAL HEALTH

COMMON MENTAL DISORDERS (CMD)

SEVERE MENTAL DISORDERS (SMDs)

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS (C & AMHDs)

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS (SUDs)

USE OF PHQ-9

DISPENSING MEDICATION AS PRESCRIBED BEFORE FROM HIGHER LEVELS. SUICIDE RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT BY GATEKEEPERS. ESTABLISH LINKAGE WITH NGOs, OTHER GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS, FAITH HEALERS, AND OTHER SECTORS. |

AWARENESS

IDENTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT OF CMDs, SMDs, SUDs, and C&AMHDs. SUICIDE RISK MITIGATION. REGULAR FOLLOW-UP ANY UPWARD REFERRAL IF NEEDED. |

Multi-disciplinary care when needed. TELECONSULTATION FACILITIES can be used for access to service providers at higher levels. TELECONSULTATION FACILITIES for constant support and supervision of personnels working at lower levels. |

The major advantages and disadvantages of integrating mental health into primary health care are as follows:

Advantages:

Accessibility – Primary health care is mostly close to where people live.

Less stigma – Seeking treatment from general health care is often less stigmatizing, especially in countries like India, where having psychiatric disorders carry a huge stigma.

Acceptability – Services offered in general care settings are much more acceptable than being treated in a psychiatric facility.

Universal coverage – Treatment can be done for both physical and mental health problems at the same setting.

The majority of common mental disorders can be managed at this level.

The additional pressure on higher levels by both inappropriate reference and also late identification, leading to more severe issues, can be decreased.

Disadvantages:

Need for a proper training and supervision of the human resources involved.

Proper support and ongoing assistance to be given to workers at this level as many a times they feel unequipped and are reluctant to prescribe psychiatric medication.

Availability of psychiatric medications to be done at this level with smooth running of its supply, storage, and distribution is difficult.

The mental health gap intervention guide (mh-GAP IG) released from WHO[10] can also serve to be an excellent resource to train non-specialists in mental health care. It provides evidence-based guidance and tools for assessment and integrated management of mental, neurological, and substance disorders by using clinical decision making protocols. It is highly effective and needs only 5–7 minutes for application. A systematic review of the implementation of the guide in various LMIC countries has already shown promise for training a huge population of non-specialists.[11]

Recommendations as per the WHO mhGAP intervention guide

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION is described in Table 5:

Table 5.

Modes of infrastructure development as per mhGAP intervention

| Modes of using the guide | Involvement of infrastructure and resources (as per mhGAP IG) |

|---|---|

| Local adaptation of the guide for training the informal health service people available |

|

| Training of non-specialists |

|

| Clinical practice at primary care settings |

|

| Digital initiatives like apps and other gadget-based technological advances |

|

| Training of specialist para medical force in sub-speciality areas |

|

Establishing implementation team (Box 1)

Box 1: Steps of establishing an implementation team

A dedicated team depending upon the geographical area to be covered should be made with proper delineation of purpose and responsibility.

Utilizing already available team resource can be helpful.

Should include members from other sectors like civil society, policy makers, service providers etc.

The task can be subdivided in task-forces and clear identification of their function to be formulated.

2. Situation analysis (Box 2)

Box 2: Situation analysis

Analysing the need and gap of resources and the available resources.

The belief systems and cultural connotations of mental health disorders to be taken into account.

The general pattern of health seeking behavior in that population.

Existing national policies.

Identifying possible barriers.

3. Implementation plan proper (Box 3)

Box 3: Implementation plan proper

WHERE- facilities where implementation to be done.

WHEN- timeline of adaptation, training schedules, supervision activities

WHAT- resources needed and available- financial, human and infrastructure

WHO- who will be trained and existing knowledge base of the trainees

HOW- improving communication across different systems

4. Adaptation strategies (Box 4):

Box 4: Adaptation strategies

The protocol should be made acceptable as per the local context by using local terms and usage of IEC materials should be in line with existing mental health policies.

Different stakeholders to be involved.

Experts from relevant disciplines to be involved.

5. Training and supervision (Box 5):

Box 5: Training and supervision

Needs co-ordinated effort both from specialists and non-specialists.

The duration should be determined as per the local adaptation and existing knowledge.

The training can be imparted by a cascade plan where a master facilitator trains ‘trainers’ who in turn trains the non-specialist front line health workers.

The trainers should be specialists in mental health and also be good facilitators and problem-solvers.

Supervision should be done by trainers to assist that the skills and knowledge learnt from the training are turned into clinical practice.

Continuous motivation should be provided to provide good quality care be the trainees.

Help in managing difficult cases.

Ensure supply of medicines and other support systems for implementation.

Provide support to health care workers experiencing stress.

6. Monitoring and evaluation

Box 6: Monitoring and evaluation

Need to assess whether the training does any impact or not.

Collection and analysis of data from all levels to be done.

Statistics of indicators like percentage of non specialists trained, facilities with uninterrupted supply of medicines, number of support and supervisory visits to each health facility etc., to be monitored at intervals.

Mental health services in general hospitals

General Health Psychiatric Units (GHPUs) are the psychiatric wings of a medical college or general hospital. It is in line with the essence of NMHP, where integration of mental and physical health care is emphasized on. They now serve as the main resource for training and research in mental health in India. The main disadvantages lie in the fact that acute management needs to be followed by adequate rehabilitation services which are lacking in this setting, leading to a revolving door phenomenon. Also, such hospitals are still scarce and are mostly in big cities, leading to a hindrance in accessibility.

Recommendations regarding GHPUs

Incorporation of psychiatric care in general hospital settings helps in hospitalization during the acute phase of illness without stigma per se, and co-morbid physical conditions can also be managed alongside. Strengthening of GHPUs has always been a focus in NMHP. There has been upgradation in infrastructure and equipment in this setting to upgrade the training resources for both under-graduate and post-graduate students. The main focus in this sphere lies in building up and shaping the human resources to meet the unmet workforce requirement needed for adequate mental health service delivery.

Manpower development schemes (Scheme-B of NMHP) also involve this level. Government Medical Colleges/Government Mental Hospitals are being supported for starting/increasing intake of PG courses in Mental Health under NMHP. The current focus in building more human resources trained in mental health is one of the backbones in strengthening human resources. The current mental health infrastructure in terms of human resource and bed ratio is bleak in our country. The various ways of specialist man-power development by strengthening post-graduate curriculum are discussed later.

Community mental health services

This includes day care centers, rehabilitation services, hospital diversion programs, mobile crisis teams, group homes, and supervised residential services. A combination of approaches as per need is an absolute necessity. The need for hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization can be effectively minimized by this level of infrastructure. Lack of effective community mental health service leads to prolonged institutionalization or landing up being homeless. Effective collaboration with other services like primary care, informal, and general hospital services is a dire necessity.

Recommendations for this service

Day care centers: They provide rehabilitation and recovery services to persons with mental illness so that the initial intervention with drug and psychotherapy is followed up and relapse is prevented. They help in enhancing the skills of the family/caregiver in providing better support care. They provide opportunities for people recovering from mental illness for successful community living.

Residential/long-term continuing care center: Chronically mentally ill individuals, who have achieved stability with respect to their symptoms and have not been able to return to their families and are currently residents of the mental hospitals, will be shifted to these centers. Residential patients in these centers will go through a structured program which will be executed with the help of a multi-disciplinary team consisting of psychologists, social workers, nurses, occupational therapists, vocational trainers, and support staff.

Long stay facilities and specialist services

Mental hospitals should be limited, and de-institutionalization should be planned. High costs, poor clinical outcomes, and violation of human rights pose problems in mental hospitals, and thus, spending on them the scarce financial resources available for mental health is disadvantageous.

Recommendations at this level

The process of de-institutionalization is important, but a gradual and planned approach is necessary and proper availability of other resources needs to be ascertained before it. Otherwise, there are chances of marginalization and homelessness.

The mental hospitals are being upgraded to Centers of Excellence in Mental Health under Manpower development Scheme A of NMHP. It plans to start/strengthen courses in psychiatry, clinical psychology, psychiatric social work, and psychiatric nursing.

Up-gradation of two Central MH Institutes to provide neurological and neuro-surgical facilities on the pattern of NIMHANS (CIP, Ranchi and LGB, Tezpur) is also on the way.

Recommendations for incorporation of persons with mental illness (PWMI) in main-stream social life

Provision of employment as per educational qualification and current cognitive status – patients can be rehabilitated to their ongoing employment or can be employed in areas where the patient can currently function. Governmental initiatives in placement of jobs for persons with past mental illness in remission can be helpful.

Housing of patients by provision of various housing schemes for a proper rehabilitation.

Support group interventions like self-help groups leading to improved coping skills, acceptance of illness, and adherence to medications like Alcoholic Anonymous to be promoted in community levels.

Focusing on the role of family in PWMI by family therapy and other interventions involving family to be planned in community levels.

Crisis resolution and home-based treatment (CRHT) is a community model of mental health care delivery which is non-existent in India, where care is provided by a multi-disciplinary team at home settings. A model was adapted by GMCH, Chandigarh, which covered more than 250 families, and the initial review showed that it is cost-effective, feasible, and replicable.

DIGITAL MENTAL HEALTH INITIATIVES

The current digital mental health initiatives in India and their salient points with focus to the scope of infrastructure development are discussed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Various digital mental health initiatives in India

| Digital platform | Salient features | Scope of infrastructure development |

|---|---|---|

| MANAS (Mental Health and Normalcy Augmentation System) Tele-MANAS |

Launched by the Government of India on April 14, 2021. Initial mobile app version launched to encourage positive mental health in the 15–35 years age group. Tele-MANAS current comprehensive mental health care service with a toll-free number (18008914416) which provides free access to the counselors. (Currently 51 Tele Manas cells, 23 Mentoring Institutes and 5 Regional Co-ordinating centers) Scaling up mental health resources, video consultations, and implementation of a full-fledged mental health service network and extending services to vulnerable groups and remote locations are the main objectives. |

Increasing the coverage by training more mental health professionals (training of trainers) who in turn can serve to be nodal persons for training. IEC activities to spread the knowledge of such a toll-free number to be existing and promoting people to seek help if needed (usage of flyers available in official website can be used). Integration with e-sanjeevani needs to be more smooth. Networking to ensure that the callers who need help from specialists are linked to the nearest available in person mental health facility. |

| E-Manas Karnataka (Mental Health care Management System) | Comprehensive mental health management system with 4 modules. Launched by Karnataka State Mental Health Authority. Health information to be integrated at one place and thus can be accessed with consent. |

Integration between the modules needs to be seamless. Data security to be ensured as patient details are available. |

| ESSENCE (Enabling translation of Science to Service to Enhance Depression Care) | Launched by Sangath, a Goa-based non-profit organization. Funded by US National Institute of Mental Health. Collaborations between Harvard University, various partners in South Asia, and Government of Madhya Pradesh. Main focus on training of community level workers via digital methods and comparison with conventional methods. |

Can be extended to other states to train their health staff if funding is feasible. |

| Amma Manasu (Mother’s Mind) | Maternal mental health program launched by the health department of Kerala. Addresses women mental health during pregnancy and post-partum. The mother and child tracking system is utilized, and mental health care is linked to regular ante-natal and post-natal visits. |

Use of this model can be very helpful in identifying and early diagnosis of maternal mental health issues. An easy 4-item questionnaire to screen parental stress/depression can be made part of all ante-natal and post-natal visits so that maternal depression is pickled up early. |

| NIMHANS ECHO Model[12] | Hub and spoke tele-mentoring model aimed to bridge the urban rural divide. Counselors from rural and underserved districts of Chattisgarh were periodically mentored by NIMHANS multi-disciplinary specialists by smartphone app. Focus on patient centric learning in mental health and addiction. |

Project ECHO is the extension of the project to build capacity in reducing disparities between urban and rural areas. |

| Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) | Initiated by Dept. of Psychiatry PGI Chandigarh, involving remote sites from Northern India. It is an online fully automated system with interlinked modules for various stages of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. |

Integration of digital technology and information and communication technology for delivering clinical psychiatry in primary and secondary health care settings can serve as a model. |

| Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment (SMART) Mental Health Project | Initiative by George Institute for Public Health. Carried out in West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh Technology-enabled electronic decision support system (EDSS) was used to deliver mental health services by primary health care workers. |

Digital technology can be used for the purpose of screening mental disorders. |

| POD Adventures | Developed as a part of project PRIDE, one of the world’s largest adolescent mental health research programs at Sangath. Lay counselor-guided problem solving intervention through mobile app |

App development targeting problem solving steps – problem identification, option generation, and creating a ‘Do it ‘plan for adolescent health group is an excellent option and can be taken up as initiatives in a larger scale. |

| Mann Mela | First digital museum aimed at addressing mental health issues faced by youth of India. Describes mental health stories using art and technology to exhibit first person stories of mental trauma, breaking stigma and recovery. |

Very innovative in addressing adolescent issues. |

| HELPLINES UMMEED (HOPE) |

By Government of Rajasthan, a dedicated helpline for children through a toll-free number 0141-4932233. Children can directly speak with counselors and seek support. Parents can get counseling on engaging children in recreational activities. Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Govt of Uttar Pradesh, with various other Government sectors. |

Children-dedicated helplines should also be made at national levels to handle various child and adolescent mental health needs. |

| Muskurayega India (India will smile) | Mental health counselors providing tele-counseling support to students and general public. | |

| DELHI CARES | Initiative by Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR), Targeted at school students under mental stress due to and post COVID-19. | |

| Toll-free number as mental helpline numbers at a nodal level and also institute levels for all medical, paramedical, and nursing colleges in the state of West Bengal. | A novel initiative of West Bengal University of Health Sciences. Have also published a mental health awareness booklet for all students. |

Can be applied to all health universities and also other universities and institute levels. |

Recommendations for digital initiatives

MANAS app developed by Government of India to be extended to all age groups including children.

State governments can work on state level initiatives like ‘e-Manas’ and ‘Amma Manasu’ for their own states to upgrade mental health service delivery.

Imparting training to primary level workers can be planned through digital initiatives like NIMHANS Echo model.

Tele counseling support to students (like the initiative of WBUHS) should be promoted widely.

Use of technology-based solutions can be an innovative way of handling resource limitation, and public–private partnerships in this regard need to be strengthened.

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based mental health initiatives can also be a way forward as they would help in access to treatment without stigma and in the scanty available resources. But there remains a chance for its inadequacy as the parameters taken in AI are not well explained yet.

FUNDING FROM THE GOVERNMENT AND SCOPE OF DEVELOPMENT

As per the latest Public Information disseminated by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare on February 4, 2022, the Government is supporting implementation of DMHP under NMHP in 704 districts in India with a financial assistance of up to Rs. 83.20 lakhs per district per year. The Center of Excellence upgradation was done for 25 centers, and 19 Governmental Medical Colleges were strengthened to focus on 47 PG Departments in Mental Health specialties. The financial support for establishing each Center of Excellence was increased from Rs. 30 crores (in the 11th Five Year Plan) to Rs. 36.96 crores per center. Sufficient financial assistance was extended to the three central institutes – NIMHANS Bengaluru, CIP Ranchi, and LGBRIMH Tezpur.

Recommendations for effective fund utilization

Ensure implementation of the fund allocated to each district by constant monitoring and supervision.

Focus on man-power development by training in mental health in both post-graduate and under-graduate levels.

Financial resource allocation should also be decentralized as the majority of mental health budget is allocated to specific institutions.

Focus on decreasing the out-of-pocket expenditure for mental illness, which would lead to better coverage and utilization of resources.

The government's total expenditure on mental health as % of total government health expenditure is mere 1.30 (Mental Health Atlas 2017), which can be increased.

SPECIAL INITIATIVES FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Children and adolescents form the backbone of future society, and mental health and well-being should be nurtured from an early stage to ensure active participation in the society.

Recommendations in accordance with national education policy by the Ministry of Education[13]

Taking a whole school approach which involves prevention, promotion, and management of mental health and well-being.

Training of teachers and other resource persons in schools about flag signs, risk factors, and what they can do in childhood mental health issues and concerns (like attachment issues, separation anxiety, school refusal, communication issues, inattention and hyperactivity, conduct issues, excessive Internet use, intellectual disability, specific learning disability, autism spectrum issues or anxiety, depressive states).

Training of teachers in adolescent mental health issues and concerns (body image, self-esteem issues, psychosomatic concerns, bullying, conduct and delinquency, loss and grief, gender identity, relationships, problematic Internet use, anxiety, and depression).

Teachers to be trained to handle emotional and behavioral emergencies in schools like child sexual abuse, aggression and violence, substance use and other addictive behaviors, self-harm, and suicidal behaviors.

A collaborative approach among parent–teacher–counselor and student.

Various checklists to screen or diagnose early identification of childhood issues to be used by teachers.

Mental health promotion and awareness through posters already provided in the guide.

Life skills training through life skill education and ‘Peer educators’.

Suicide prevention

The National Suicide Prevention Strategy was launched by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare on November 2022 – the first of its kind in the country with a target of achieving reduction in suicide mortality by 10% by 2030. From 2019 to 2022, the suicide rate has increased from 10.2 to 11.3 per 100,000 population with the highest frequency in daily wage workers.

Recommendations as per the National Suicide Prevention Strategy

The various initiatives involve establishing an effective surveillance mechanism by the next 3 years and establishing psychiatric OPDs in all districts through DMHP within the next 5 years. It also aims in integrating a mental well-being curriculum in all educational institutions in the next 8 years and developing guidelines for responsible media reporting of suicides and restricting access to means. The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment has launched a 24/7 toll free helpline “KIRAN”, and the Ministry of Education has launched “Manodarpan” as part of suicide mitigation.

STRENGTHENING THE POST-GRADUATE (PG) CURRICULUM FOR MAN-POWER DEVELOPMENT AS SPECIALIST RESOURCES

The National Medical Commission has focused on competency-based PG curriculum, and also, the quantity and quality of training have been a point of discussion. There are various areas of concern like quality assurance pan institutions, less or no focus on newer modalities of treatment like rTMS, tDCS, variance of training received in GHPUs vis-à-vis Mental Hospital-based training centers, lack of training in neurology, lack of objective assessment techniques, and issues related to teachers' training.[14]

RECOMMENDATIONS

Psychiatry training should focus on providing ethical, evidence-based diagnosis and treatment to patients.

Enough competency and focus on trainees having adequate teaching skills, research methodology, and epidemiology.

Listening and communication skills to be focused upon.

Knowledge about developmental psychology and childhood disorders, sleep disorders, and sexual disorders should be adequate.

Adequate skill about electroconvulsive therapy and its application should be ensured.

All subspeciality knowledge should be adequate enough for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Management of alcohol withdrawal syndromes and other common psychiatric emergencies should be focused upon.

The mandatory requirement of psychiatry teachers in a psychiatry department is very less, and with all ongoing duties of faculties, it is much necessary that the minimum requirement may be increased for adequate training.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH HUMAN RESOURCES FOR MENTAL WELL- BEING

Human resource development should involve an approach where major focus is put on the lower base of the WHO pyramid level thus promoting self-care and strengthening informal community care.

Mental health literacy should be promoted to make aware to all individuals about self-care strategies like developing skills to manage stress, ability to discuss emotional problems and seeking help when needed.

Informal community care to be focused by involving various human resources involved in public welfare like teachers, police personnels and effectively using the services rendered by NGOs and other services at community level.

Integration of primary health services with mental health will effectively mainstream mental health and also reduce stigma associated.

Manpower development schemes of NMHP to be focused and increase in trained mental health specialists should be prioritized with effective training.

Long term rehabilitation should also be focused in a community level and thus incorporating persons with mental illness into mainstream life and thus manpower to be trained accordingly.

Digital mental health initiatives are way forward and dispersing the knowhow in an effective manner via such means would be effective in reaching the larger mass.

Special attention to be focused on children and adolescents and suicide prevention to be done and man-power at all levels should be trained in these aspects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Batool M, Kumar T. Scenario of health infrastructure in India and its augmentation after independence. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2019;8:2103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: A handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization World mental health report: transforming mental health for all 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sagar R, Dandona R, Gururaj G, Dhaliwal RS, Singh A, Ferrari A, et al. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–61. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy RS. National mental health survey of India 2015–2016. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:21–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_102_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Italy: WHO; 2017. Mental health atlas 2017 country profile India. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/mental-health-atlas-2017-country-profile-india. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 04] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Italy: WHO; 2007. The optimal mix of services: WHO Pyramid framework. Available from: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/content/document/The%20optimal%20mix%20of%20services%20for%20mental%20health.pdf. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 04] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Portal, National Health Mission, Goverment of India Operational Guidelines Mental, Neurological and Substance Use (MNS) Disorders Care. New Delhi (IN); 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: Mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) World Health Organization; 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keynejad R, Spagnolo J, Thornicroft G. WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: Updated systematic review on evidence and impact. BMJ Ment Health. 2021;24:124–30. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrotra K, Chand P, Bandawar M, Sagi MR, Kaur S, Aurobind G, et al. Effectiveness of NIMHANS ECHO blended tele-mentoring model on integrated mental health and addiction for counsellors in rural and underserved districts of Chhattisgarh, India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;36:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Education, Government of India . Modular Handbook for Teachers and allied stakeholders. India: GOI; 2022. Early identification and intervention for mental health problems in school going children and adolescents. Available from: https://kvsangathan.nic.in/sites/default/files/hq/MoE%20Mental%20Health%20Module%206th%20Sep%2022.pdf. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 04] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh OP. Postgraduate psychiatry training in India–National Medical Commission competency-based PG curriculum. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64:329–30. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_426_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]