Abstract

In this case series, three unrelated male housemate cats were treated repeatedly with injections of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for intercat aggression and urinary house soiling. All three cats subsequently developed multiple recurrent mammary adenocarcinomas and underwent numerous surgical resections. This report describes the clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical findings in these three cats and highlights the potential for mammary carcinomas to develop in male cats years after receiving MPA injections. Extended survival times and a long delay between the administration of the progestin injections and the onset of mammary neoplasia are noted. Estrogen and progesterone receptor staining was performed on some of the tumors and the complex role of hormones in the pathogenesis and the prognosis of feline mammary carcinoma is discussed. Clinicians using MPA should institute life-long surveillance of their feline patients for mammary tumors.

Synthetic progestins, including oral megestrol acetate and injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) (Depo-provera; Upjohn), have been used frequently by feline practitioners for a variety of reproductive, behavioral and dermatologic conditions. The potential deleterious side effects of progestins in cats include adrenocortical suppression, acromegaly, polydipsia, polyphagia, diabetes mellitus and pathologic changes in mammary glands. 1 Fibroepithelial hyperplasia has been strongly linked to progesterone in young intact female cats, and may be related to progestin therapy in older castrated males and spayed females. 2,3 Mammary carcinoma development in non-domestic female felids treated at zoos with melengestrol, an implantable progestin for contraception, has been well described. 4 Both benign and malignant mammary tumors have been reported in male and female domestic cats treated with MPA. 5–7 The role of hormones in the pathogenesis of mammary carcinoma in the domestic male cat is complex. One study found 8/22 (36%) cats with mammary carcinoma had a history of progestin administration. 8 Several studies have implicated growth hormone (GH) as a mediator of progestin-induced mammary tumorigenesis in both dogs and cats. Progestins, both exogenous and endogenous, have been shown to increase GH production within the mammary gland itself. This mammary-derived GH may have endocrine, para/autocrine, as well as exocrine effects and may be directly and indirectly involved in mammary epithelial proliferation and tumorigenesis. 9–11 While a causal relationship between progestin treatment and tumor formation may be difficult to prove as the latency period is so long, these previous studies provide a plausible mechanistic explanation for the mammary tumor development in these cats.

In this small case series, three unrelated male housemate cats were treated repeatedly with injections of MPA for intercat aggression and urinary house soiling. All three cats were middle aged, adult domestic shorthairs that were obtained as strays and appeared to be neutered males. These cats lived strictly indoors with several other neutered males and females and prior therapy with a variety of medications including benzodiazepenes, buspirone, megestrol acetate and phenobarbital was ineffective in controlling the cats' undesirable behaviors. The cats' owner gave informed consent authorizing medroxyprogesterone injections and was educated about the potential adverse effects of progestins. Repeated injections (range, 7–16) were given to each of the three cats over a number of years. The injections proved to be an effective and convenient treatment for the undesirable behaviors, however, all three cats developed multiple recurrent malignant mammary tumors for which they underwent surgical resections over the course of the next several years. Cryptorchidism was detected and corrected during surgery in two of the cats. Long-term outcomes were determined in all of the cats. This report describes the clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical findings in these three cats and highlights the potential for mammary carcinomas to develop in male cats years after receiving medroxyprogesterone injections.

Cat 1 was castrated with documentation of two scrotal testicles being removed 2 years prior to presentation for urine marking and intercat aggression. Urinalysis had been unremarkable and no response was seen with sequential trials of phenobarbital, alprazolam and buspirone. Depot injections of 100 mg MPA (25 mg/kg) were then administered which rapidly led to a reduction in urine marking and aggressive behavior. A total of 16 injections were given over nearly a 5-year period on a variable schedule (ranging from 2 to 13 months apart) as requested by the cat's owner. No side effects were noted during the course of treatment.

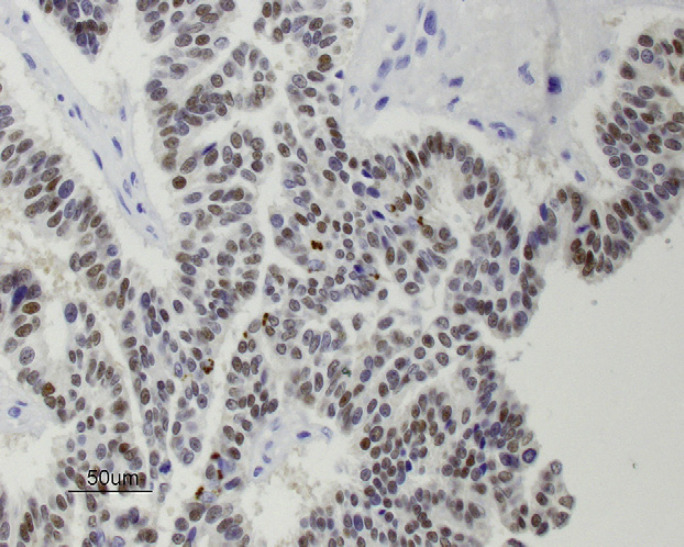

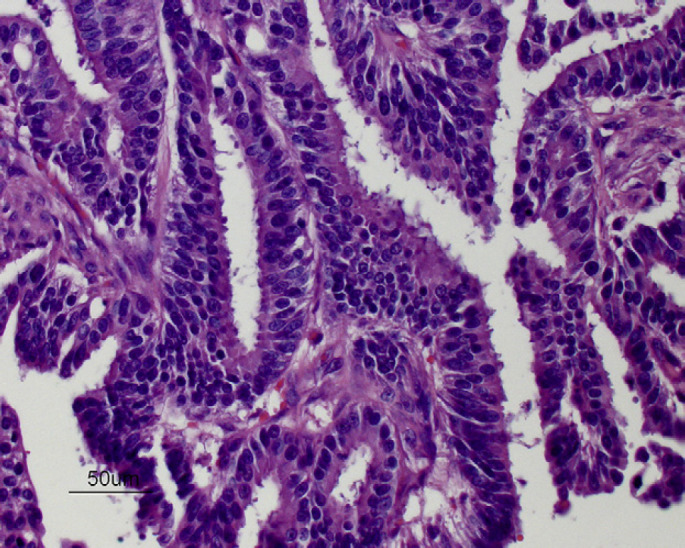

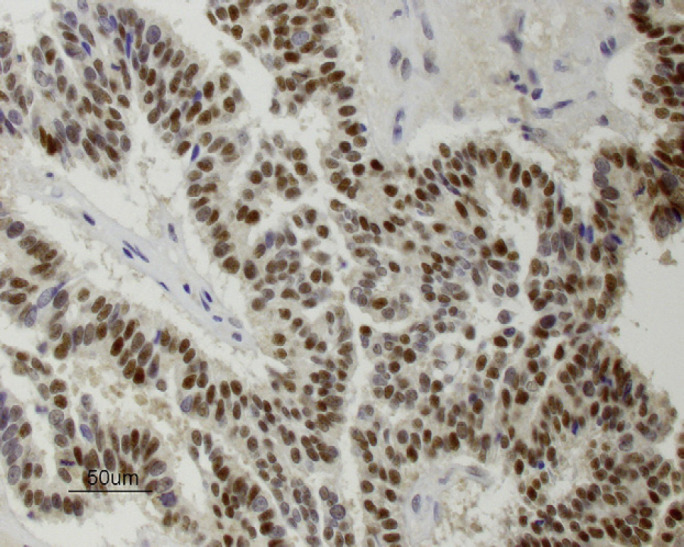

Six years after the final injection had been given, a 3 cm sized mass was detected near the right fourth mammary gland and a 0.5 cm sized mass was found within the left second mammary gland. Pre-anesthetic blood tests (total protein, glucose, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, alanine transaminase) were within the normal range except for a mildly increased hematocrit (50%), and thoracic radiographs were normal. A right chain radical mastectomy and a left second simple mastectomy were performed and histology revealed adenocarcinoma at both sites with variable pleomorphism and moderate numbers of mitoses (Fig 1). Immunohistochemical staining of the adenocarcinoma was positive for estrogen receptors (ERs) (Fig 2) and progesterone receptors (PRs) (Fig 3). No adjunctive therapy was provided and the cat remained free of disease until 18 months later when a 1 cm sized mass was noted along the right cranioventral thoracic wall. Pre-anesthetic blood tests were normal. A wide excision was performed and histology was consistent with recurrent mammary adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining of this tumor was negative for both ERs and PRs.

Fig 1.

Mammary adenocarcinoma from a male cat (cat 1) exposed to injections of MPA (hematoxylin and eosin, ×400).

Fig 2.

Immunohistochemical staining for ERs (brown is positive) in mammary adenocarcinoma from cat 1 (×400).

Fig 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for PRs (brown is positive) in mammary adenocarcinoma from cat 1 (×400).

Thoracic radiographs showed no evidence of metastasis and the cat had no further recurrence until 1 year later when three 0.5 cm sized masses were found along the left side of the sternum and axillary space. Lumpectomies were performed including removal of the left axillary lymph node. Histopathology again confirmed recurrent mammary adenocarcinoma and lymph node metastasis with marked cellular atypia and frequent mitotic figures. Immunohistochemical staining of the mammary adenocarcinoma was negative for ERs and PRs. No further treatment was given and the cat was euthanased 3 months later with terminal signs of anorexia, blindness and hyphema. Necropsy was not permitted and the cause of the decline was not determined. Total survival from first tumor occurrence to death was 953 days.

Cat 2 was presented for evaluation with signs of intercat aggression and occasional urine marking. The cat's owner stated that another veterinarian had performed castration, however, only one testicle was found within the scrotal sac and it was unclear if exploratory surgery was undertaken to try to locate the cryptorchid testicle. Subsequent hormone assay showed a level of testosterone consistent with that of an intact male (testosterone 1.26 ng/ml, reference range for castrated male cats less than 0.5 ng/ml, Diagnostic Laboratory, New York State College of Veterinary Medicine). Laparotomy revealed tissue remnants near the bladder suggestive of a prior surgery and histology demonstrated a spermatic cord with vas deferens but no identifiable testicle. Urinalysis was normal. Separate trials of diazepam and megestrol acetate failed to resolve the signs of fighting and urine marking.

Depot injections of 100 mg MPA (15 mg/kg) were administered on a variable schedule (ranging from 2 to 14 months apart) according to requests by the cat's owner. The injections eliminated signs of aggression and urine marking. The cat received 16 injections over a 6.5-year period and no side effects were reported during that time. Two months after the last injection a 2 cm sized mass near the right third mammary gland was found. Thoracic radiographs and pre-anesthetic blood tests (hematocrit, total protein, glucose, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, alanine transaminase) were normal and right chain radical mastectomy was performed. A cryptorchid testicle was found just outside of the right inguinal ring and removed during surgical dissection.

Mammary adenocarcinoma was confirmed histopathologically. The cryptorchid testicle displayed diffuse, marked atrophy of the seminiferous tubules with moderate interstitial cell hyperplasia and a normal epididymis. Immunohistochemical staining of the mammary adenocarcinoma was negative for ERs and PR, although some areas of lactational hyperplasia stained ER positive. No adjunctive treatment was given. The cat's aggressive behavior and urine marking resolved completely. Six months later, multiple 0.2–0.5 cm sized masses were detected near the left second and third mammary gland and a left chain mastectomy was performed. The cat's owner declined further blood testing and histopathologic evaluation of the tissues. Four additional mammary mass excisions were performed (all less than 0.5 cm in size) over the next 3.5 years. Only one of the excised masses was examined histologically and it confirmed mammary adenocarcinoma. One month after the final excision the cat was euthanased with signs of respiratory distress and femoral arterial thromboembolization. At necropsy, no gross evidence of pulmonary metastasis was found. Total survival from first tumor occurrence to death was 1438 days.

Cat 3 was presented for evaluation with a similar history of chronic intercat aggression and urine marking. The cat's owner assumed that he had been castrated and claimed to have tried an unspecified number of medications for these conditions with no response. There were no palpable testicles in the area of the scrotal sac. Due to the improvement observed with his other male cats, the cat's owner requested injections of MPA. Depot injections of 100 mg MPA (14 mg/kg) were administered per owner request and a prompt, complete resolution of the aggressive signs and urine marking was noted. A total of seven injections were given over a 6-year span and no side effects were noted during that time. Ten months after the last medroxyprogesterone injection was given, multiple 0.2–0.5 cm masses were found near the left fourth mammary gland. Pre-anesthetic blood tests (hematocrit, total protein, glucose, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, alanine transaminase) and thoracic radiographs were normal and simple mastectomy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed mammary adenocarcinoma with pleomorphism, high mitotic rate, and lymphatic invasion. Immunohistochemical staining of the mammary adenocarcinoma was negative for ERs and PRs, however, some areas of atypical hyperplasia stained positive for PRs. No adjunctive treatment was given and 2 months later a left chain radical mastectomy was performed due to regional recurrence of mammary tumors. A rudimentary testicle was found and removed during dissection around the outside of the left inguinal ring. The testicle was not examined histologically. The cat's signs of aggression and urine marking permanently resolved. Three months later, a right chain mastectomy was performed due to the development of multiple mammary tumors on that side. Thoracic radiographs were normal. The cat had a recurrence of mammary tumors on the right side 18 months later and multiple 0.3–0.5 cm sized tumors were excised. No samples were submitted for histology after these recurrences. The cat remained disease free for the next 3 years. He developed hyperthyroidism and chronic renal disease as a geriatric cat and was euthanased with no necropsy performed. Total survival from first tumor occurrence to death was 3099 days.

A summary of the association of the three cats' MPA injections with the occurrence of their mammary tumors and their survival times is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Association of MPA injections with the occurrence mammary tumors and survival times in the three cases.

| Cat 1 | Cat 2 | Cat 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate age at time of death | 15 years | 13 years | 20 years |

| Survival time from recognition of first mammary tumor | 953 days | 1438 days | 3099 days |

| Total number of MPA injections given to each cat | 16 in 1714 days | 16 in 2321 days | 7 in 2225 days |

| Cumulative lifetime dose of MPA given to each cat | 1600 mg | 1600 mg | 700 mg |

| Interval between first injection and first mammary tumor | 3908 days | 2381 days | 2537 days |

| Interval between last injection and first mammary tumor | 2554 days | 60 days | 312 days |

Immunohistochemical evaluation of ERs and PRs was performed on formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections of six of the cats' mammary tumors with microwave antigen retrieval and a DAKO automatic universal staining system. Briefly, murine monoclonal antibodies against (ERs) (antibody clone ER88 [Bionex]) at a 1:40 dilution and (PRs Immunotech) at a 1:50 dilution were applied to sections for 30 min at room temperature. Immunodetection used a DAKO Envision+ kit containing a ENVmono-HRP enzyme labeled polymer conjugated to a mouse secondary antibody. The polymer was devoid of avidin and biotin, which significantly reduced or eliminated nonspecific staining. Visualization of antibody binding was obtained with a DAB+ 3,3-daminobenzidine solution and hematoxylin counterstaining. Feline ovary and uterus were used as positive and controls.

Mammary tumors in male cats are very uncommon. Compared with female cats, male mammary tumors represent approximately 1–5% of the total number of mammary carcinomas diagnosed in feline species. 8 Intact queens are at greater risk, due to the effects of repeated cycles of endogenous estrogen and progesterone hormones on mammary epithelium. Cats spayed before 1 year of age are at significantly decreased risk of mammary carcinoma development. 12 While most feline mammary tumors occur in intact females, spayed females and intact or castrated male cats exposed to progestins are also at risk of developing mammary neoplasia. 2,13,14 Spontaneous mammary carcinoma in male cats does occur but is considered rare. 2,8

Limited information is published specifically about mammary tumors in male cats but in general the biologic behavior seems to be similar in both sexes. Most mammary tumors in male cats are malignant (classified as carcinoma or adenocarcinoma) with an aggressive clinical course characterized by local recurrence after resection and pulmonary metastasis. In one report of 39 male cats with mammary carcinomas, the mean age at diagnosis was 12.8 years with an overall survival time of 344 days. 8 There was no statistically significant difference in survival times between males that had a history of exposure to progestins and those that did not. Tumor size (>3 cm) and lymphatic invasion was negatively correlated with survival. 8 These prognostic factors are similar in female cats 15–18 and suggest that early surgical intervention is warranted. Insufficient data is available in male cats comparing the effectiveness of simple lumpectomy to mastectomy or chain mastectomy, however, smaller surgical procedures may result in local recurrence. Studies of female feline mammary carcinomas show that poorly differentiated tumors with a high mitotic index or tumors with high argyrophilic nucleolar organizer region (AgNOR) counts are correlated with shorter survival times. 14,19 Molecular studies performed on cat mammary tumors suggest that Ki-67 positivity, 20 vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 21 or cyclin A expression, 22 and the HER/neu phenotype may also have prognostic significance. 23 Treatment is primarily surgical. Although adjunctive chemotherapy for treatment of systemic metastasis is logical, the results of studies examining outcome in treated cats have been variable. Some reports appear to show benefit 24,25 while other recent work has been unable to demonstrate any improvement in survival. 26 Studies evaluating the efficacy of radiation therapy and hormonal receptor blockade for feline patients with mammary carcinoma have not yet been published.

The presence or absence of ERs and PRs in mammary gland tumors has been used for prognosis in both feline and human studies. 27 In cats, lower numbers of ERs and PRs have been reported in malignant mammary tumors than in normal mammary glands or benign tumors. Thus the loss of hormonal receptors in mammary tumors may be considered indicative of malignant progression. 2,28,29 In humans, low ER and PR levels have been associated with increased tumor grade, decreased tumor-free intervals and survival, and poor response to hormone therapy. 4 A recent report describing mammary carcinomas in melengestrol-treated zoo felids found that 4/16 treated cats expressed PRs and 1/16 expressed ERs. 4 All of the cats, however, had high-grade carcinomas with metastases and the authors concluded that PR status did not correspond to prognosis in zoo felids.

Prolonged treatment of dogs with depot MPA has been shown to increase plasma levels of GH by inducing the expression of a gene encoding GH in hyperplastic mammary epithelial cells. 9 In cats, progestin-induced fibroadenomatous changes in the mammary glands have been associated with locally enhanced GH expression. 10 These findings suggest that progestin-induced GH enhances the development of mammary tissue in an autocrine and/or paracrine manner and may possibly promote tumorigenesis by stimulating proliferation of susceptible, and sometimes transformed, mammary epithelial cells. 11 Neither GH plasma levels nor GH production by the mammary tumors were evaluated in the cats during this study.

The three male domestic cats in this report were each given repeated injections of MPA after other attempts at treatment for the undesirable behaviors of intercat aggression and urine marking had failed. Progestin administration at that time was an accepted standard of care 30 and while the treatments were effective, a delayed and likely cumulative effect, the development of mammary adenocarcinoma, was observed in all three cats. This adverse effect was particularly regrettable in light of the fact that 2/3 males were subsequently found to be cryptorchid, and that complete castration would presumably have eliminated the behaviors without having had to resort to progestin therapy. The dose of MPA administered to these cats (range of 14 mg/kg–25 mg/kg) was empirically derived but within the range of published recommendations. 23 Whether the dose of MPA or the number of injections that were given is related to the oncogenesis is unknown. Naturally occurring mammary tumors in unspayed female cats develop under the influence of repeated cycles of estrogen and progesterone and one hypothesis is that progesterone may promote mammary tumor development. 31 In a report of MPA-induced mammary adenocarcinomas in mice, investigators speculated that the medroxyprogesterone might induce tumor growth directly via PRs. 32 MPA is widely used a contraceptive injection in women but epidemiological data does not support any increased risk of breast cancer. 33 Although a direct cause and effect relationship between the administration of the MPA injections and the development of mammary adenocarcinomas in the three cats in this report is difficult to prove, the association is striking and compelling.

The interval of time between the first injection and the first mammary tumor, an average of 2942 days in the three cats, seems noteworthy. Carcinogenesis due to chemical, physical or hormonal factors is known to have extended induction/latency period. To the author's knowledge, there is no published information concerning the time delay between the administration of progestins and the onset of neoplastic mammary changes. Clinicians using MPA should institute life-long surveillance of their feline patients for mammary tumors and stop the injections if any changes in the mammary glands develop. The extended survival times of the three male cats in this report, averaging 1830 days, were significantly longer than previously reported survival times in cats with mammary carcinomas. Median survival time of 451 days was reported in seven male cats that developed mammary carcinoma with a history of progestin exposure. 8 The adenocarcinomas evaluated in the three cats in this case series were all histologically high-grade and some displayed lymphatic invasion, however, all the tumors were 3 cm or less in size and were removed promptly. All of the cats developed several tumors over an extended period of time, some of these were likely recurrence from the initial tumor, but others were clearly new primary tumors as they appeared in different glands. Local recurrences were common despite the fact that radical mastectomies were performed in all cats. It is possible that this is due to a field carcinogenesis effect of the previous progestin therapy on the entire mammary tissues in these cats. However, only 1/3 cats had strong PR and ER positive tumors, suggesting that these tumors were independent of hormonal stimulation. This does not necessarily imply that hormones, specifically progesterone, are not implicated in tumorgenesis, but may rather mean, that over time, as the tumor becomes more anaplastic it also becomes autonomous and independent of hormonal stimulation. 29,31 This is supported by the fact that normal tissues around the tumors were consistently positive for both PR and ER. Attentive monitoring by the cats' owner and timely surgical intervention likely contributed to the cats' longevity.

In conclusion, the use of MPA injections in feline patients may be associated with the development of mammary adenocarcinomas, sometimes years later. Although synthetic progestins may be efficacious for a variety of behavioral, dermatologic and reproductive conditions in cats, veterinarians should consider the risk of inducing mammary neoplasia with progestins versus alternate treatment options.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Michael Goldschmidt of the University of Pennsylvania for helping perform the estrogen and progesterone receptor immunohistochemistry staining.

References

- 1.Plumb D.C. Medroxyprogesterone acetate, Veterinary drug handbook, 5th edn, 2005, Pharmavet: Stockholm, WI. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore A.S., Ogilvie G.K. Mammary tumors. Ogilvie G.K., Moore A.S. Feline oncology, a comprehensive guide to compassionate care, 2001, Veterinary Learning Systems: Trenton. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayden D., Johnston S., Kiang D., Johnson K., Barnes D. Feline mammary hypertrophy/fibroadenoma complex: Clinical and hormonal aspects, Am J Vet Res 42, 1981, 1699–1703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAloose D., Munson L., Naydan D.K. Histologic features of mammary carcinoma in zoo felids treated with melengestrol acetate (MGA) contraceptives, Vet Pathol 44, 2007, 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez F.J., Fernandez B.B., Chertack M., Gage P.A. Feline mammary carcinoma and progestogens, Feline Pract 5, 1975, 45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loretti A.P., Ilha M.R., Ordas J., de las Mulas J. Martin. Clinical, pathological and immunohistochemical study of feline mammary fibroepithelial hyperplasia following a single injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, J Fel Med Surg 7, 2005, 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misdorp W. Progestagens and mammary tumours in dogs and cats, Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 125 (suppl 1), 1991, 27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skorupski K.A., Overley B., Shofer F.S., Goldschmidt M.H., Miller C.A., Sorenmo K.U. Clinical characteristics of mammary carcinoma in male cats, J Vet Intern Med 19, 2005, 52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mol J.A., van Garderen E., Rutteman G.R., Rijnberk A. New insights in the molecular mechanism of progestin-induced proliferation of mammary epithelium: Induction of the local biosynthesis of growth hormone (GH) in the mammary gland of dogs, cats and humans, J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 57, 1996, 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rijnberk A., Mol J.A. Progestin-induced hypersecretion of growth hormone: An introductory review, J Reprod Fertil Suppl 51, 1997, 335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Garderen E., de Wit M., Voorhout W.F., et al. Expression of growth hormone in canine mammary tissue and mammary tumors. Evidence for a potential autocrine/paracrine stimulatory loop, Am J Pathol 150, 1997, 1037–1047. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overley B., Shofer F.S., Goldschmidt M.H., Sherer D., Sorenmo K.U. Association between ovariohysterectomy and feline mammary carcinoma, J Vet Intern Med 19, 2005, 560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misdorp WZ, Else RW, Hellman E, Lipscomb TP. Histologic classification of mammary tumors of the dog and cat. Vol. 7: Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1999: 58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden D.W., Barnes D.M., Johnson K.H. Morphologic changes in the mammary gland of megestrol acetate-treated and untreated cats: A retrospective study, Vet Pathol 26, 1989, 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacEwen E.G., Hayes A.A., Harvey H.J., et al. Prognostic factors for feline mammary tumors, J Am Vet Med Assoc 185, 1984, 201–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viste J.R., Myers S.L., Singh B., Simko E. Feline mammary adenocarcinoma: Tumor size as a prognostic indicator, Can Vet J 43, 2002, 33–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castagnaro M., Casalone C., Bozzetta E., De Maria R., Biolatti B., Caramelli M. Tumour grading and the one-year post-surgical prognosis in feline mammary carcinomas, J Comp Pathol 119, 1998, 263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito T., Kadosawa T., Mochizuki M., Matsunaga S., Nishimura R., Sasaki N. Prognosis of malignant mammary tumor in 53 cats, J Vet Med Sci 58, 1996, 723–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castagnaro M., Casalone C., Ru G., Nervi G.C., Bozzetta E., Caramelli M. Argyrophilic nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs) count as indicator of post-surgical prognosis in feline mammary carcinomas, Res Vet Sci 64, 1998, 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castagnaro M., De Maria R., Bozzetta E., et al. Ki-67 index as an indicator of the post-surgical prognosis in feline mammary carcinomas, Res Vet Sci 65, 1998, 223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millanta F., Lazzeri G., Vannozzi I., Viacava P., Poli A. Correlation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression to overall survival in feline invasive mammary carcinomas, Vet Pathol 39, 2002, 690–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami Y., Tateyama S., Rungsipipat A., Uchida K., Yamaguchi R. Amplification of the cyclin a gene in canine and feline mammary tumors, J Vet Med Sci 62, 2000, 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winston J., Craft D.M., Scase T.J., Bergman P.J. Immunohistochemical detection of HER-2/neu expression in spontaneous feline mammary tumours, Vet Comp Oncol 3, 2005, 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeglum K.A., de Guzman E., Young K.M. Chemotherapy of advanced mammary adenocarcinoma in 14 cats, J Am Vet Med Assoc 87, 1985, 157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novosad C.A., Bergman P.J., O'Brien M.G., et al. Retrospective evaluation of adjunctive doxorubicin for the treatment of feline mammary gland adenocarcinoma: 67 cases, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 42, 2006, 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeil C.J., Sorenmo K.U., Shofer F.S., et al. Evaluation of adjuvant doxorubici-based chemotherapy for the treatment of feline mammary carcinoma, J Vet Intern Med 23, 2009, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munson L., Moresco A. Comparative pathology of mammary gland cancers in domestic and wild animals, Breast Dis 28, 2007, 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston S.H., Hayden D.W., Kiang D.T., Handschin B., Johnson K.H. Progesterone receptors in feline mammary adenocarcinoma, Am J Vet Res 45, 1984, 379–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millanta F., Calandrella M., Bari G., Niccolini M., Vannozzi I., Poll A. Comparison of steroid receptor expression in normal, dysplastic, and neoplastic canine and feline mammary tissues, Res Vet Sci 79, 2005, 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hart B.L. Objectionable urine spraying and urine marking in cats: Evaluation of progestin treatment in gonadectomized males and females, J Am Vet Med Assoc 177, 1980, 529–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lana S.E., Rutteman G.R., Withrow S.J. Tumors of the mammary gland. Withrow S.J., Vail D.M. Small animal clinical oncology, 4th edn, 2007, Saunders Elsevier: St Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molinolo A.A., Lanari C., Charreau E.H., Sanjuan N., Pasqualini C.D. Mouse mammary tumors induced by medroxyprogesterone acetate: Immunohistochemistry and hormonal receptors, J Natl Cancer Inst 79, 1987, 1341–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaunitz A.M. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancer, J Reprod Med 41 (suppl 5), 1996, 419–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]