Abstract

Despite the lack of validated methods for differentiating feral from frightened socialized cats upon intake to animal welfare agencies, these organizations must make handling and disposition decisions for millions of cats each year based on their presumed socialization status. We conducted a nationwide survey of feline welfare stakeholders to learn about methods used to evaluate and categorize incoming cats, amount of time cats are held before assessment, disposition options available, and the level of cooperation among welfare agencies to minimize euthanasia of ferals. A wide variety of assessment methods were described and only 15% of 555 respondents had written guidelines. Holding periods of 1–3 days were common, and cats deemed feral were often euthanased. About half the shelters transferred ferals to trap–neuter–return (TNR) programs at least occasionally. Results highlight the need for validated assessment methods to facilitate judicious holding and disposition decisions for unowned cats at time of intake.

Each year, at least 2.5 million cats enter animal shelters nationwide (ASPCA unpublished data). 1,2 Many are pets relinquished by their owners, but at least half are free-roaming cats. 3–5 Generally, ‘free-roaming’ is a term used for any cat living outdoors at least part of the time, including feral; semi-feral, loosely owned cats; lost or abandoned pet cats and currently owned cats allowed outside. 6 We define true feral cats as those who did not receive appropriate social interaction with people during the socialization period and hence remain wary of them throughout adulthood. 7–10 However, cats may alter their behavior towards humans through their life-times or in different environments, further complicating assessments. Feral cats typically remain too frightened of humans to be placed into a home as a companion animal.

Semi-feral, loosely owned cats have had some degree of socialization with people and these cats may approach a human caregiver for food or even solicit some social interaction depending on the cat and the circumstance. Abandoned and lost pets generally were once well-socialized and lived in close association with people, but due to their subsequent experiences, such as exposure to an unfamiliar environment, many display fearful behavior when approached. However, these cats can often overcome their fear of people under certain conditions and once again become pets.

The manner in which an animal shelter, rescue group or spay/neuter program handles an incoming cat, and the disposition options available for the cat, depend heavily on how the cat is categorized. As adult feral cats do not make appropriate pets, they are often best managed with a trap–neuter–return (TNR) program under the charge of a skilled feral cat caregiver. Feral kittens less than 7 weeks of age may become adoptable pets if placed into a systematic socialization program. 8,11 Many semi-feral, loosely owned cats as well as formerly abandoned or lost pets may, with careful treatment and thoughtful placement, be adoptable as companion animals.

When any cat enters an unfamiliar environment such as an animal shelter or other welfare agency, however, it is prone to displaying fearful behavior. Even well-socialized pet cats can become fearfully aggressive or motivated to withdraw or escape. As a result, it can initially be very difficult to accurately determine which cats are feral and which cats have the potential to be reclaimed or adopted as a pet. There are currently no validated methods of differentiating the various categories of cats upon intake to animal sheltering or other welfare agencies.

These agencies are, nonetheless, forced to make handling and disposition decisions for a large number of cats. Cats must generally be sheltered for a minimum holding period to permit the owner to reclaim the animal as prescribed by state and local ordinances. However, in some circumstances, there is no legal requirement to hold cats who are thought to be feral and it is the policy of many shelters to euthanase cats deemed to be feral. Holding feral cats unnecessarily can create staff safety risks and subjects the cat to chronic stress caused by confinement in close proximity to humans and other animals. 12 This affects the cat's physical and mental well-being. 13 Holding cats also requires use of limited shelter resources including cage space, food, and staff time that must be allotted judiciously. On the other hand, euthanasing or placing a socialized cat that could be adopted into a TNR program could be an inappropriate disposition decision.

While fearful pet cats can, upon shelter intake, experience high stress levels and, therefore, appear behaviorally similar to feral cats, they may begin to display more characteristic behavior after several days or weeks in the shelter when their stress levels begin to subside. 14–16 Each shelter's policy of holding cats before a disposition decision is made, therefore, must weigh the benefits of holding cats who are potentially able to be adopted as pets or reclaimed by their owners against the drawbacks of holding cats who are truly feral.

Due to the lack of research identifying valid methods of differentiating feral from non-feral cats upon intake to shelters or other welfare organizations, most agencies have developed their own formal or informal guidelines for assessing their incoming cats. We conducted a nationwide survey of cat welfare stakeholders, with the objectives of: (1) describing the range of processes by which incoming cats are assessed and categorized, (2) detailing the amount of time cats are held before making that determination, and the disposition options available for each category of cats, and (3) estimating the ability of different types of welfare organizations to interface or cooperate with external agencies to increase feline live release rates.

Materials and Methods

Subject selection

We asked contacts known by the authors at five national organizations (National Animal Control Association, Society for Animal Welfare Administrators, Humane Society of the United States, American Society for the Protection of Animals, and the Cat Fancier's Association) to send the request for participation (which included the survey website link) out to their members by email, newsletter, website, and/or listserv. A group of about 800 spay/neuter clinics in the US were emailed the request for participation. We also posted the request on the Campus Feral Cat listserv and the Association of Shelter Veterinarians' listserv (both national in scope). In addition, contacts in shelters in New York, Tennessee, and Michigan were asked to circulate the request through formal and informal regional networks. Specific animal behaviorists involved with cat behavior were also contacted. We asked everyone to distribute the request as widely as possible.

Survey design and administration

In the email inviting participation, an introductory letter explained the purpose of the questionnaire, assured confidentiality, and identified the researchers involved. There were nine questions in the survey (a copy is available from the first author). Question 1 was an open-ended question that asked for the guidelines or criteria used to assess whether a cat was feral or not and provided some example criteria. The second question asked if the guidelines were in a written format (yes/no response format with space for comments). The third question (open-ended) asked how soon after entering a program did the respondent's group decide if the cat was feral. The fourth question asked if cats determined to be feral went into a socialization program (yes/no response format with space for comments). The fifth question asked if they had misidentified a cat as feral, what lead to the discovery of this error (open-ended). For brick and mortal shelters (those with a physical facility to hold animals), question 6 asked about the procedure for handling cats identified as feral (multiple-choice format) with options: euthanasia after holding period, euthanased on identification as feral, return to colony if eartipped, transfer to a local TNR organization, spay/neuter and return to caregiver, or ‘other’ (with space for comments). Background questions for all respondents included whether the respondent's program was primarily an animal control organization, non-profit shelter with building, foster program without a building, spay/neuter clinic, TNR program, colony caregiver, or other interested individual (multiple-choice format) (question 7) and in what state the program was located (question 8). The last question (question 9) asked if we might contact the respondent about this project, and, if so, to please provide contact information (which was optional). The survey was pre-tested by several animal welfare professionals for clarity and organization. After revision, the survey was posted on SurveyMonkey.com on March 3, 2009 and closed April 2, 2009. Respondents accessed the survey via a secure weblink provided in the survey participation invitation.

Statistical analysis

Yes/no or multiple-choice questions were summarized using percentages. Responses to the guidelines for determining if a cat was feral were summarized by dividing them into the type of behavioral assessments conducted; the measures taken during these assessments; and the type of information gathered about the cat outside a formal behavior assessment, such as observations of undisturbed behavior, information from the caretaker, or physical appearance. For example, representative responses were, ‘Does the cat approach the caretaker? Can the cat be touched and how does it respond? Does the cat talk? Is it a kitten less than 8 weeks old? Does the cat slow blink? Is the cat wearing a collar of some sort?’ ‘Avoids humans but closely observes them. Will run from food supply if human approaches. General demeanor of wariness and distrust of humans.’ ‘We are a spay/neuter clinic and rely on what people are telling us. If they bring us a cat in a trap that does not have a known home, we consider him/her feral.’ These examples would be classified as: the cat's response to human approach in its home environment; vocalization; physical appearance; eyes; presence of collar, neutered or declawed status; the cat's behavior around food; and information from caregiver about cat's behavior or personality.

Duration of holding the cat was an open-ended question as we were unsure what types of answers we might receive. Some responses were in the form of a narrative. For example, ‘Whenever possible, I like to give a cat at least a week, with visits daily by the same person.’ Some responses were very unambiguous, such as ‘pretty much immediately’ or ‘within our 5-day holding period’. Other responses indicated a usual time range, but also that some other options were sometimes available. For example, ‘We generally determine their adoptability upon arrival but will isolate for no less than 48 h to evaluate any behavioral changes’. Others provided a typical range such as 3–5 days. This is why we chose to focus on the minimum holding time for each organization. Some responses also separated kittens from adults in the holding times. The shortest times were used in this situation.

Disposition of cats was obtained from questions 4 and 6 as well as from comments. The socialization comments were primarily used to determine if the respondent was referring to a kitten only socialization program or one that included adult feral cats. Our original intention was to determine if adult cats were socialized but there was some ambiguity in the question wording (based on the responses). Sometimes information that could be used to determine if feral cats are ever sterilized and returned was found here as well. For example, ‘Our shelter is so small we try to get them spayed/neutered and then to a farm or an open area or back where they came from if the people will continue to care for them.’ Additional information for assessing transfer of cats or TNR could come from comments like ‘If eartipped they are held for feral cat rescue organization which returns them to a colony.’ ‘We advocate for TNR and make every attempt to return the cat to its location once it has been spayed/neutered, vaccinated and eartipped. However, for cats without a known caretaker or those that are injured, they are euthanased once they are determined to be feral.’ ‘TNR if surrenderer is willing, euthanase if unable to TNR, return to colony if microchipped or colony is known.’

Responses for mistakenly identifying a cat as feral were also summarized from the written responses into 29 response categories. Many of the comments simply reiterated the criteria or time to determine if a cat is feral or not and were not included in responses to this question. We were looking for specific incidents and details like ‘Just after time, while we were waiting for a suitable barn home, the cat got friendlier and stopped acting feral’. This would be classified as behavior changes after time to settle in. An example of a cat displaying social behavior towards humans that indicated the cat was not truly feral would be ‘A cat was very vocal in the trap and responded to human voices. Upon release from the trap it hugged a staff member.’ An example that indicated a change in cats' behavior when assessed in a quiet, low stress environment was ‘It is also important to take into account the housing of individual felines before deciding it is feral. For example, a very social cat who is terrified of dogs will act like a feral cat if asked to live in a cage where there are many barking dogs, especially if the dogs can approach the cage and the cat has nowhere to hide.’

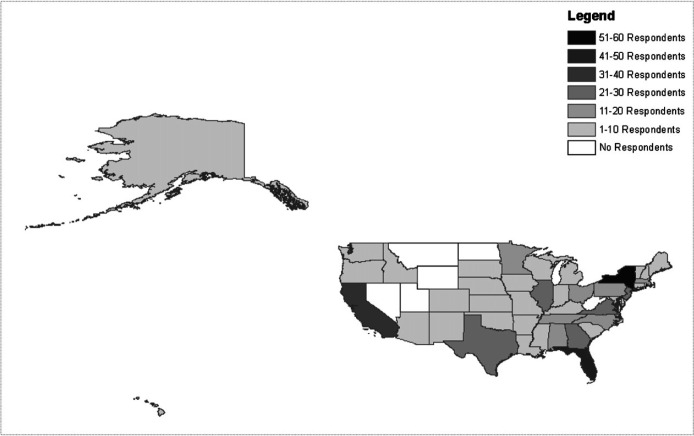

Cross-tabulations were performed between type of responding organization, and whether written assessment guidelines existed, the minimum holding/assessment time, feral cat socialization, and disposition options utilized. The US respondents' locations were mapped by state to describe their geographic distribution.

Results

While we have no reason to believe the respondents to this survey were not representative of the general population of feline welfare stakeholders, due to the haphazard sampling method used, the results should not be generalized beyond the population of respondents.

Objective 1: assessing incoming cats (questions 1, 2, 7, 8 and comments)

Five hundred and fifty-five respondents from 44 states, 11 respondents from Canada, and one each from the UK, Guam and Puerto Rico provided at least partially completed surveys. Fig 1 shows the geographic distribution of US respondents' locations by state (when provided). Five hundred and eighteen respondents provided the type of program. The most common types of programs were non-profit brick and mortar shelters (32%, 168/518), TNR programs (18%, 93/518), and animal control organizations (15%, 76/518). Seven percent of respondents (37/555) did not answer this question or provide information in the open-ended comments allowing classification. Six respondents were able to be categorized into type of program based on comments (‘from personal experience with my own feral colony’, ‘those of us doing TNR’ ‘after cats enter the shelter…hold 7–20 days,’ ‘am a law enforcement officer’) and are included in Table 1. Overall, only 14% of programs (73/508 who answered this question) had written guidelines for assessing their cats. Table 1 shows this information stratified by type of organization.

Fig 1.

Locations of the 496 United States respondents to this survey who provided a location.

Table 1.

Responses (518 with data on type of program) related to feral cat identification guidelines and disposition options for feral cats stratified by the type of program.

| Variable | Non-profit brick and mortar shelter (n=168) | TNR program (n=93) | Animal control organization (n=76) | Colony caregiver or rescuer (n=58) | Spay/neuter clinic (n=45) | Foster program without a building (n=36) | Individual (n=36) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Are there written guidelines? (10 missing) | ||||||||

| No | 138 (83) | 83 (89) | 61 (82) | 53 (85) | 36 (84) | 31 (89) | 33 (94) | 435 (85) |

| Yes | 28 (17) | 10 (11) | 13 (18) | 9 (15) | 7 (16) | 4 (11) | 2 (6) | 73 (15) |

| Minimum holding or assessment time * (101 missing) | ||||||||

| 1 day or less | 37 (24) | 22 (31) | 15 (21) | 11 (23) | 18 (75) | 3 (11) | 6 (26) | 112 (27) |

| 2 days | 14 (9) | 5 (7) | 7 (10) | 3 (6) | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | 4 (17) | 36 (9) |

| 3 days | 46 (30) | 18 (26) | 24 (34) | 10 (21) | 0 | 7 (25) | 3 (13) | 108 (26) |

| 4 days | 2 (1) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 9 (2) |

| 5 days | 16 (10) | 2 (3) | 13 (19) | 2 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 | 35 (9) |

| 7 days | 40 (26) | 21 (30) | 10 (14) | 21 (44) | 4 (17) | 13 (46) | 9 (39) | 117 (28) |

| Is TNR or return to the colony/caregiver ever an option * | ||||||||

| Yes | 94 (56) | 94 (100) | 37 (49) | 36 (87) | 35(78) | 26 (72) | 22 (61) | 340 (66) |

| No/ not applicable | 74 (44) | 0 | 39 (51) | 28 (13) | 10 (22) | 10 (28) | 14 (39) | 178 (34) |

| For cats/kittens who are feral, do they go into a socialization program * | ||||||||

| Yes | 60 (37) | 38 (42) | 15 (21) | 29 (50) | 14 (45) | 19 (56) | 11 (34) | 186 (39) |

| If specified, adult socialization | 4(7) | 7(18) | 0 | 3 (10) | 0 | 5 (26) | 3 (27) | 15(8) |

| If specified, kitten socialization | 44 (73) | 27 (71) | 12 (80) | 17 (59) | 11 (79) | 14 (74) | 5 (45) | 123 (66) |

*These variables were calculated using answers to specific questions as well as write-in comments from the respondents.

With regards to guidelines or criteria used to assess incoming cats, respondents provided a comingled mixture of assessment techniques and locations (eg, try to pick up the cat; try to touch the cat in the trap), measures made or data collected (eg, the cat tries to escape; the cat's pupils are dilated; the cat is aggressive) and information gathered without performing any formal assessment (eg, the cat's appearance, information from the caretaker). These widely varying responses, which we attempted to group into some common themes, are presented in Table 2. We found no widely-accepted, over-arching criteria or information-gathering guidelines among the responses.

Table 2.

Summary of cat assessment techniques and collected data. Any of these assessments may be performed at intake and/or after a ‘settling in‘ period.

| Behavioral assessments/tests |

| Human approaches cat while eating |

| Human approaches cat in trap/cage |

| Cat is exposed to an unfamiliar cat |

| Cat is touched in trap/cage with an inanimate object (eg, pencil, spoon, feather, Assess-A-Hand) |

| Cat is petted |

| Attempt is made to pick cat up |

| Cat's cage is cleaned |

| Cat is removed from trap/cage |

| Data collected during behavioral assessments/tests |

| Biting or scratching |

| Body carriage |

| Charging, striking or lunging |

| Ear position |

| Escape, avoidance or hiding attempts (intensity, frequency, duration) |

| Eyes (pupil dilation, eye contact, blinking) |

| Flight distance |

| Freezing |

| Gait (eg, slinking) |

| Muscle tension |

| Piloerection |

| Respiration rate; panting |

| Rubbing on objects |

| Self-maintenance behaviors (eating, drinking, grooming, using litter box) |

| Tail position |

| Vocalization (and response to human meow) |

| Observational indications outside a testing situation |

| Cat's behavior is observed in trap/cage when left undisturbed |

| Apparent size of cat's home range outdoors |

| Cat's behavior in its home environment when people are nearby |

| Cat's behavior towards food |

| Cat's response to human approach in its home environment |

| Condition, cleanliness, dishevelment of trap/cage |

| History of cat |

| Information from neighbors about cat's behavior |

| Information from caretaker about cat's behavior or personality |

| Willingness of cat to approach caretaker's door |

| Medical conditions |

| Presence of other feral cats in the area |

| Cat's physical appearance (eg, coat or body condition) |

| Presence of collar, neutered or declawed status |

| Presence of injuries/scars |

| Transportation method (carrier vs trap) |

Objective 2: holding times and dispositions (questions 3, 4, 5, 6 and comments)

The question about time to determine if a cat was feral was categorized into minimum holding/assessment periods. Table 1 summarizes these minimum times by type of organization. For brick and mortar shelters, Table 3 indicates the disposition of cats if they were determined to be feral. The original five answer categories for this question were expanded into combination options for analyses based on the ‘other’ answers given. The question about whether respondents placed feral cats into a socialization program was used in conjunction with comments to determine total numbers of programs that had any socialization program. When respondents indicated that the program applied specifically to adults or to kittens, this was also documented. One hundred and eighty-six of 479 (39%) respondents who provided information on this question did have programs for feral kittens, adults or both (Table 1). Of these, 138 indicated whether the program was for adults (15/186 or 8%) or kittens (123/186 or 66%).

Table 3.

Disposition of feral cats for programs that have a brick and mortar (physical facility) shelter (n=244) when respondents answered this question.

| Procedure for handling known feral | Non-profit brick and mortar shelter (n=168) N (%) | Animal control organization (n=76) N (%) | Total N (%) |

| Euthanased after holding period | 31 (43) | 31 (19) | 62 (26) |

| Euthanased as soon as determined to be feral | 23 (14) | 4 (6) | 27 (11) |

| Either of the above | 3 (4) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) |

| TNR or euthanased depending on circumstances | 27 (17) | 18 (25) | 45 (19) |

| Spay/neuter and return to owner | 23 (14) | 2 (3) | 25 (11) |

| TNR | 9 (6) | 2 (3) | 11 (5) |

| If eartipped, return to colony | 8 (5) | 5 (7) | 13 (6) |

| Transfer to local TNR group | 9 (6) | 2 (3) | 11 (5) |

| Sanctuary, TNR | 8 (5) | 1 (1) | 9 (4) |

| All of the above | 15 (9) | 3 (4) | 18 (8) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 2 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Ferals not admitted | 6 (4) | 0 | 6 (3) |

| Not answered | 4 (2) | 3 (4) | 7 (3) |

Of the 288 respondents who indicated that a cat they previously thought to be feral was subsequently found not to be feral, this discovery was most frequently cited as due to: the cat's behavior changing after it had time to settle in or acclimate (mentioned by 144 or 50% of respondents), the cat began to display tolerant, social or affiliative behavior in response to human contact or handling (65 or 23%), the cat began to offer social behavior when humans were nearby (vocalization, blinking, solicitation, approach) (56 or 19%), and the cat's behavior was different when it was assessed in a quieter, less stressful or more familiar environment (40 or 14%).

Objective 3: cooperation with other organizations (questions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and comments)

Brick and mortar shelters (non-profit and animal control)

Among the 244 responding brick and mortar shelters (non-profit and animal control), 11 (5%) indicated that their primary method for handling feral cats was to transfer them to TNR groups. An additional 17 (7%) wrote comments about their feral cat disposition options that indicated some type of cooperation with other groups (for a total of 28/244, or 12%). In detail, these 17 shelters included 10 respondents (4%) who stated that they provided TNR or euthanased depending on the circumstances but, when possible, also transferred to a TNR organization if the cat was eartipped; five of the 244 shelters (2%) that provided TNR services also could transfer to a TNR organization; one shelter (0.4%) had access to a small feral cat sanctuary and one shelter (0.4%) tried to work with local cat groups to transfer the feral cats out of the shelter (although most ferals were still euthanased).

All respondents

We also summarized efforts to increase live release rates across all respondents by examining both their responses to the question about disposition options for cats deemed feral as well as all their written comments. Any indication that TNR, transfer to a TNR program or return to a managed colony was ever an option was tallied. Overall, 340/518 respondents (66%) indicated that TNR or return to colony/caretaker was at least sometimes possible (Table 1).

Discussion

We received a large number of responses to this survey, often with long and detailed comments. We also received replies from organizations from almost all the American states and had representation from different regions of the country. We believe that this level of response, particularly given the short turn-around time and the details requested in the survey, indicates a wide audience for a still-to-be-developed valid and easily applied tool to determine if a cat is or is not feral. Our belief that determining feral status is an important issue for sheltering organizations was supported by our results. As mandatory stray cat holding periods can range from 0 h to over 7 days, holding cats for that length of time has both resource and welfare implications.

A very small number of programs had written guidelines. Brick and mortar shelters and animal control facilities did not have substantially higher frequencies of written guidelines than other types of programs. The variability in what types of criteria were used and the lack of standardization is a concern as euthanasia and resource-heavy decisions are made based on cats' presumed socialization status.

Overall, organizations used a wide range of behavioral assessments while the cat was in the trap, in a cage or still outdoors (before trapping). On the other hand, some programs simply used the criterion that if a cat arrived in a trap it was considered to be feral, without any behavioral assessment. One common assessment technique was observing the cat's response to being touched with an inanimate object. However, some programs attempted to touch, remove from the trap or cage, or pick up cats by hand. This practice is unsafe and is not recommended if a cat is truly feral or very frightened because serious injury could result. Another common observation was that cats believed to be feral were more likely to dishevel the inside of their cage (or trap) than frightened socialized cats and were also more likely to climb the walls of the cage rather than remain motionless or hidden. This assessment is likely influenced by the cat's environment and the availability of hiding places as well as the frustration or energy level of the cat.

Some programs, especially TNR and foster groups, were able to obtain information about the cat before the cat entered their program. Insight into the level of interaction with humans, especially around food, could prove useful in deciding how socialized a cat might be. Physical appearance, body condition and medical problems were often listed as helpful. However, respondents contradicted each other: some stated that cats in poor condition were often recently owned cats while others indicated that they were truly feral cats. Age of the cat, prior experience (such as being an indoor/outdoor cat) gender and neuter status could also influence a cat's socialization assessment. Clearly, more data are needed to determine if this type of information is helpful or if there is too much variability among individual cats and situations to use general condition as an indicator.

At this point, there are few data to support that any of the measures used are predictive. However, some measures are reasonable approximations of validated assessment items used for felines and other species. 17–20 The authors will be exploring the predictive value of the measures in a future study.

The most frequently cited reason that a cat was mistakenly identified as feral was that the cat's behavior changed after it had more time to settle into the new environment, which was mentioned by half of all the respondents to this question. In fact, the second and third most common responses to this question were also related to a change in the cat's behavior, apparently over time, with the cat starting to respond with tolerance or affiliative behavior to human contact, or the cat beginning to freely offer social behavior to nearby humans. Many of the other responses to this question could also be related to acclimatization of the cat, including a difference in the cat's behavior when it was assessed in a quieter, less stressful environment; when it was re-assessed post-intake; after it was placed in its cage; or when it was removed from the presence of other, unfamiliar cats.

The most common disposition for feral cats by brick and mortar non-profit and animal control shelters was euthanasia with or without a holding period. A substantial number of programs euthanased cats as soon as the organization labeled them feral, often on the same day as arrival. This practice would preclude any acclimatization by the cats to the new environment and may, therefore, increase the likelihood that truly socialized cats are euthanased by mistake. It would also make it nearly impossible for the owner of a lost cat to find his/her pet.

More than 25% of the programs used some combination of disposition options depending on circumstances, with animal control programs somewhat more likely to utilize multiple options. In our experience, funding, space, and a willing transfer organization typically influence this decision. The second most common disposition was some version of TNR, which was more often an option among non-profit shelters than animal control organizations. Enhancing relationships between programs would be valuable. In addition to a willingness to select non-lethal dispositions, resources including space and funding would be needed.

We specifically asked if cats who were determined to be feral went into a socialization program. The question was apparently somewhat confusing to respondents; many wrote comments about providing different socialization options for adults versus kittens. Overall, 39% replied that they had some sort of socialization program. In examining the comments, the majority of organizations offered kitten but not adult socialization programs. Taming programs for adult feral cats can be problematic as the sensitive period for socialization effectively closes at around 8 or 9 weeks of age, 7–9 truly feral cats may take weeks, months or years to habituate to humans and may still only be comfortable with a few people. However, if an adult cat is not truly feral, a re-socialization program may provide valuable time for the cat to re-learn an affiliative response to human contact and become adoptable. Many respondents indicated that time was the most important element of deciding if a cat was feral or not.

Minimum holding times were highly varied, with 1–3 days common among all organizations and most common for animal control programs. A surprisingly high number of other groups (besides spay/neuter clinics) were able to hold cats at least 7 days. Almost two-thirds of responding programs could hold cats for a minimum of 3 days, making it possible to provide cats with a resting and adjustment period before evaluation. This may make a more accurate behavioral assessment practical. Ideally, however, a predictive assessment at, or close to, intake would be ideal for the welfare of the cats and the limited resources of the animal welfare organization.

We used several different ways of determining if programs (TNR, sanctuary, shelters, etc) interacted in positive ways with each other. To prevent response bias, we did not directly ask about collaboration with other programs (as lack of collaboration could be perceived as an admission of failure to explore all options prior to euthanasia). Also, that question would have required additional details about the specific type of collaboration we were interested in and we did not want to detract from the primary objective. The question about disposition provided some information about transfers of cats between welfare groups. Many respondents also offered comments if their disposition methods were not listed. These comments provided valuable insight into the circumstances under which transfers and collaboration were possible. The results also illustrated that some programs have separate options for cats already in TNR programs, as determined by an eartip or notch. Several animal control organizations have programs or transfer options for eartipped or notched cats that call colony caregivers to retrieve notched cats picked up by animal control officers. About half of non-TNR groups indicated that TNR or return to the colony caregiver was a possibility for disposition at least some of the time. There is no way to know if this represents the situation nationally or if our sample is biased in some way for or against TNR. Regardless, there are still many organizations that could decrease euthanasia by including TNR as an option for feral cats brought to the shelter by members of the public.

This survey highlights the need for more research focused on a standardized, validated, predictive set of guidelines for determining feral status as early in the intake process as possible. The need and interest for these guidelines in the field are apparent from the responses to this survey.

Acknowledgements

We thank the individuals who provided input during pilot testing as well as those who distributed and completed the survey. We also thank Christine Budke and Rachana Bhattarai for their assistance with the map.

References

- 1.Patronek G.J., Beck A.M., Glickman T. Dynamics of dog and cat populations in a community, J Am Vet Med Assoc 210, 1997, 637–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New J.C., Kelch W.J., Hutchison J.M., et al. Birth and death rate estimates of cats and dogs in US households and related factors, J Appl Anim Welfare Sci 7, 2004, 229–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy J.K., Woods J.E., Turick S.L., Etheridge D.L. Number of unowned free-roaming cats in a college community in the southern United States and characteristics of community residents who feed them, J Am Vet Med Assoc 223, 2003, 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy E.A., Rowan A.N. Companion animal demographics in the United States: a historical perspective. Salem D.J., Rowan A.N. State of the animals II: 2003, 2003, Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lord L.K., Wittum T.E., Ferketich A.K., Funk J.A., Rajala-Schultz P., Kauffman R.M. Demographic trends for animal care and control agencies in Ohio from 1996 to 2004, J Am Vet Med Assoc 229, 2006, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slater M. Understanding issues and solutions for unowned, free-roaming cat populations, J Am Vet Med Assoc 225, 2004, 1350–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karsh E. Factors influencing the socialization of cats to people. Anderson R., Hart B., Hart L. The pet connection: its influence on our health and quality of life, 1984, Center to Study Human–Animal Relationships and Environments, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karsh E.B., Turner D.C. The human–cat relationship. Turner D.C., Bateson P. The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour, 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaver B.V. Feline behavior: a guide for veterinarians, 2003, Saunders: St Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradshaw J.W.S., Horsfield G.F., Allen J.A., Robinson I.H. Feral cats: their role in the population dynamics of Felis catus, Appl Anim Behav Sci 65, 1999, 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe S.E., Bradshaw J.W.S. Ontogeny of individuality in the domestic cat in the home environment, Anim Behav 61, 2001, 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler M., Turner D. Socialization and stress in cats (Felis silvestris catus) housed singly and in groups in animal shelters, Anim Welf 8, 1999, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moberg G.P. Biological response to stress: implications for animal welfare. Moberg G.P., Mench J.A. The biology of animal stress: basic principles and implications for animal welfare, 2000, CABI Publishing: New York, NY, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler M.R., Turner D.C. Stress and adaptation of cats (Felis silvestris catus) housed single, in pairs and in groups in boarding catteries, Anim Welf 6, 1997, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dybdall K., Strasser R., Katz T. Behavioral differences between owner surrender and stray domestic cats after entering an animal shelter, Appl Anim Behav Sci 104, 2007, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patronek G.J., Sperry E. Quality of life in long term confinement. August J.R. Consultations in feline internal medicine IV, 2001, Saunders: Philadelphia, 621–634. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCune S. The impact of paternity and early socialization on the development of cats' behavior to people and novel objects, Appl Anim Behav Sci 45, 1995, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marston L.C., Bennett P.C. Admissions of cats to animal welfare shelters in Melbourne, Australia, J Appl Anim Welfare Sci 12, 2009, 189–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegford J.M., Walshaw S.O., Brunner P., Zanella A.J. Validation of a temperament test for domestic cats, Anthrozoos 16, 2003, 332–351. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ursin H. Flight and defense behavior in cats, J Comp Physiol Psychol 58, 1964, 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]