Abstract

PURPOSE

To examine whether cancer screening prevalence in the United States during 2021 has returned to prepandemic levels using nationally representative data.

METHODS

Information on receipt of age-eligible screening for breast (women age 50-74 years), cervical (women without a hysterectomy age 21-65 years), prostate (men age 55-69 years), and colorectal cancer (men and women age 50-75 years) according to the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations was obtained from the 2019 and 2021 National Health Interview Survey. Past-year screening prevalence in 2019 and 2021 and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs), 2021 versus 2019, with their 95% CIs were calculated using complex survey logistic regression models.

RESULTS

Between 2019 and 2021, past-year screening in the United States decreased from 59.9% to 57.1% (aPR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91 to 0.97) for breast cancer, from 45.3% to 39.0% (aPR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.89) for cervical cancer, and from 39.5% to 36.3% (aPR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.97) for prostate cancer. Declines were most notable for non-Hispanic Asian persons. Colorectal cancer screening prevalence remained unchanged because an increase in past-year stool testing (from 7.0% to 10.3%; aPR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.31 to 1.58) offset a decline in colonoscopy (from 15.5% to 13.8%; aPR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.95). The increase in stool testing was most pronounced in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations and in persons with low socioeconomic status.

CONCLUSION

Past-year screening prevalence for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer among age-eligible adults in the United States continued to be lower than prepandemic levels in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, reinforcing the importance of return to screening health system outreach and media campaigns. The large increase in stool testing emphasizes the role of home-based screening during health care system disruptions.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the delivery and receipt of routine preventive services, including cancer screenings.1 A systematic review and meta-analysis found an overall decrease of 46.7% for breast, 51.8% for cervical, and 44.9% for colorectal cancer screening tests performed from January to October of 2020.2 More recent studies reported a potential rebound in screening for colorectal, breast, cervical, and prostate cancer in the summer of 2020.3-9 However, these findings are not generalizable to the overall US population because they are based on claims databases, electronic medical records, or non-nationwide data. On the basis of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a state-specific population-based database, we reported 6%-11% declines in past-year breast and cervical cancer screening prevalence in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.10,11 The CDC also conducts the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which is a true, national survey of the US population.12 Herein, we examine changes in the receipt of screening for breast, cervical, prostate, and colon and rectum cancer during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic overall and by sociodemographic characteristics using the 2019 and 2021 NHIS.12

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Did past-year cancer screening prevalence for breast, cervical, prostate, and colorectal cancer rebound in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic to the prepandemic levels?

Knowledge Generated

On the basis of a nationally representative database, past-year screening prevalence for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer in the second year of the pandemic (2021) did not rebound to the prepandemic levels (2019), reinforcing the importance of strengthening return to screening campaigns. In contrast, past-year colorectal cancer screening during the corresponding pandemic period remained unchanged as the increase in past-year blood stool testing offset the decline in colonoscopy screening.

Relevance (I. Cheng)

-

The persistence of lower screening rates for breast, cervical, and prostate cancers in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic points to the importance of directed efforts across the health care system to strengthen cancer screening.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Iona Cheng, PhD, MPH.

METHODS

This study used the 2019 and 2021 NHIS, a cross-sectional nationwide household survey collected through the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC.12 The NHIS had a redesign in 2019 preventing comparability of estimates with those from the survey administered in previous years. As of 2019, the NHIS reports on cancer screening prevalence biyearly.12 The NHIS is usually conducted through face-to-face interviews; however, because of the pandemic, the first four months of 2021 data were collected through telephone interviews with in-person visits only as a follow-up on nonresponse/nontelephone users.12 In May of 2021, interviewers were directed to return to in-person interviews but were given flexibility to conduct telephone interviews contingent on local COVID-19 conditions.12

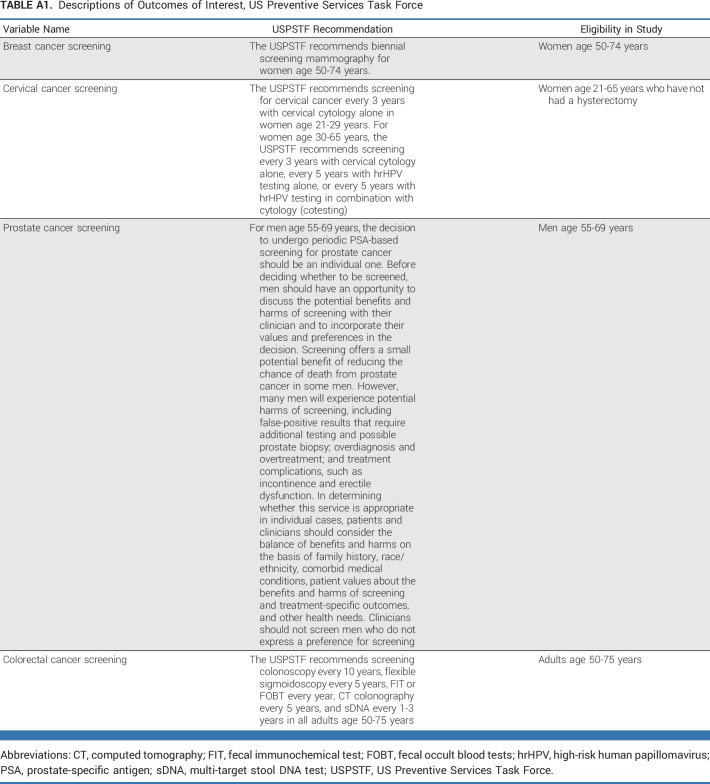

The primary outcomes were self-reported receipt of breast, cervical, prostate, and colorectal cancer screening in the past year. Lung cancer screening in the past year was not included as receipt of lung cancer screening was not available in the NHIS 2021, nor 2019.12 Respondents were considered to have received screening in the past year if they reported that they received a test within the past year (anytime < 12 months ago). As with previous studies, past-year cancer screening was the primary focus as disruptions in receipt of care because of the COVID-19 pandemic may be most closely related to past-year cancer screening compared with up-to-date (UTD) screening.10 Past-year screening eligibility was defined according to the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation (women age 50-74 years for breast, women who had not had a hysterectomy and age 21-65 years for cervical, men age 55-69 years for prostate, and men and women age 50-75 years for colorectal cancer; Appendix Table A1, online only, showing eligibility).13

Our primary exposure was the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collected in 2019 were treated as before the pandemic, whereas data collected in 2021 were treated as during the pandemic.

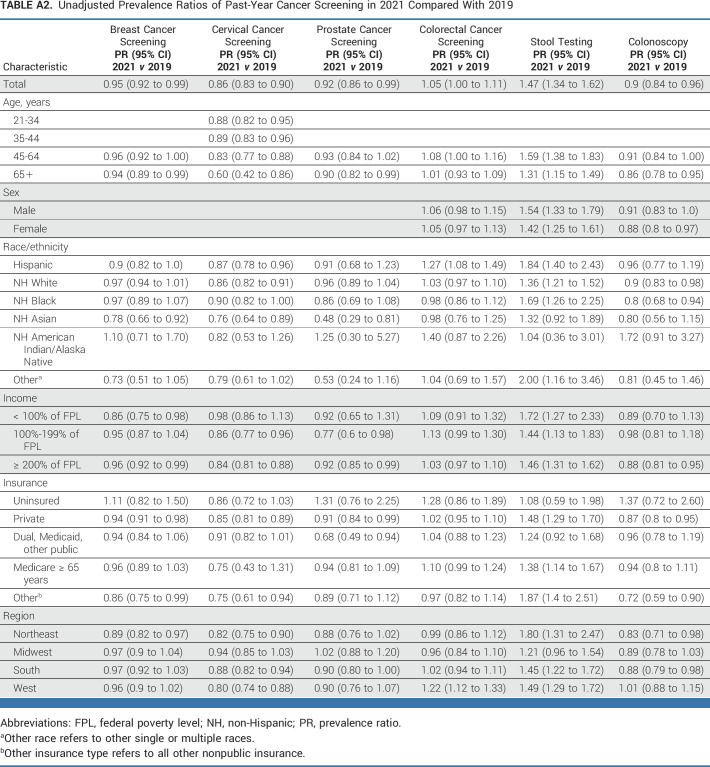

Past-year cancer screening prevalence were estimated overall in 2019 and 2021, and differences in the prevalence between survey years by sociodemographic characteristics were assessed via the chi-square test. Prevalence estimates were considered statistically unstable and suppressed if the relative standard error was ≥ 30% or the denominator of the estimate, n, was < 50. Logistic regression models were used to estimate unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs for changes between 2019 and 2021, overall, by quarter, and by sociodemographic characteristics. Models were sequentially adjusted for sex (colorectal cancer screenings only), race/ethnicity, income, insurance status, and region. All analyses were conducted in SAS and SAS-callable SUDAAN for complex survey logistic regression models. Past-year unadjusted prevalence ratios are available in Appendix Table A2 (online only).

Factors of interest included self-reported sex (men, women, for colorectal cancer only), age, income (< 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL), 100%-199% of the FPL, and ≥ 200% of the FPL), insurance status (uninsured, private, dual or Medicaid or other public, Medicare [≥ 65 years], and other insured), and geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). Race/ethnicity categories were conceptualized as a social construction of racialized groups (Hispanic, non-Hispanic [NH] White, NH Black, NH Asian, NH American Indian/Alaska Native, and NH other). A collinearity assessment was run through a regression model. No factors had a variance inflation factor > 2.5, so all remained in the model. All estimates were weighted to be nationally representative, and participants with missing values for receipt of cancer screening were dropped (breast: 0.49%/N = 68; cervical: 0.49%/N = 92; prostate: 0.9%/N = 65; colorectal: 0%/N = 0).

RESULTS

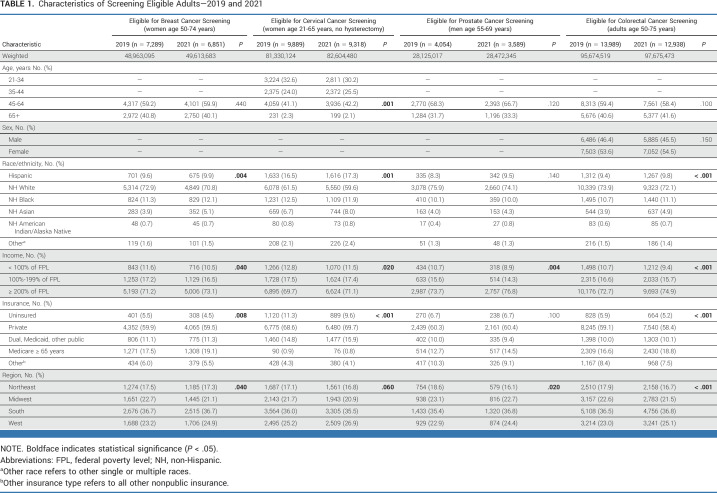

Among 2019 and 2021 NHIS adult survey participants, 7,289 and 6,851 were eligible for breast, 9,889 and 9,318 for cervical, 4,054 and 3,589 for prostate, and 13,989 and 12,938 for colorectal cancer screening (Table 1). The corresponding weighted national population estimates were 49.0 and 49.6 million persons for breast cancer screening, 81.3 and 82.6 million persons for cervical cancer screening, 28.1 and 28.5 million persons for prostate cancer screening, and 95.7 and 97.7 million persons for colorectal cancer screening. Sociodemographic characteristics of survey participants were generally similar between the 2019 and 2021 surveys, except that the 2021 survey participants had slightly higher income (eg, 73.1% of those eligible for breast cancer screening in 2021 were at or above 200% of the FPL v 71.2% of those eligible in 2019, P = .04).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Screening Eligible Adults—2019 and 2021

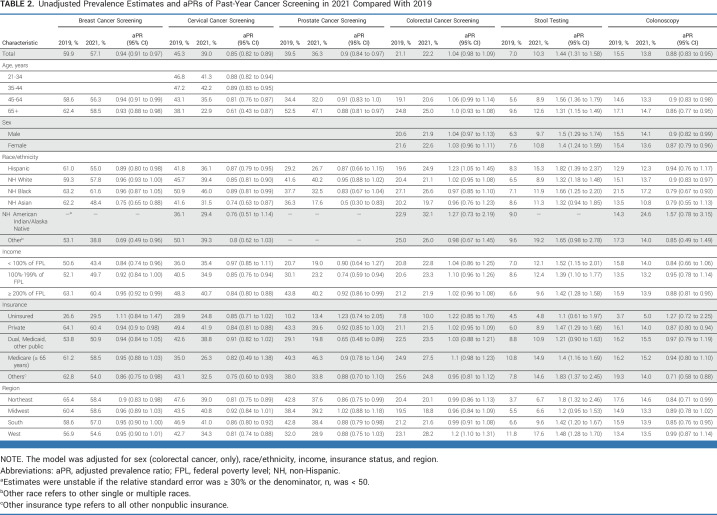

Between 2019 and 2021, overall past-year screening among age-eligible adults decreased by 6% for breast cancer (from 59.9% to 57.1%; aPR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91 to 0.97), by 15% for cervical cancer (from 45.3% to 39.0%; aPR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.89), and by 10% for prostate cancer (from 39.5% to 36.3%; aPR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.97) but was unchanged for colorectal cancer (from 21.1% to 22.2%; aPR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.09; Table 2). The stable trend in colorectal cancer screening reflects an increase in past-year home blood stool test use of 44% (from 7.0% to 10.3%; aPR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.31 to 1.58) which offset a 12% decline in colonoscopy utilization (from 15.5% to 13.8%; aPR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.95).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Prevalence Estimates and aPRs of Past-Year Cancer Screening in 2021 Compared With 2019

As shown in Table 2, significant declines in past-year screening from 2019 to 2021 for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer were largest for NH Asian persons, ranging from 25% for breast cancer (from 62.2% to 48.4%; aPR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.88) to 50% for prostate cancer (from 36.3% to 17.6%; aPR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.83). By FPL, breast cancer screening prevalence during the corresponding period declined in all FPL categories although the decrease was nonsignificantly higher in women with < 100% FPL (aPR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.96) than in those with ≥ 100% to 199% FPL (aPR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.0) or with ≥ 200% FPL (aPR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92 to 0.99). By contrast, cervical and prostate cancer screening prevalence declined in persons with 100%-199% FPL, but not in those with < 100% FPL. For example, cervical cancer screening prevalence between 2019 and 2021 declined by 15%-16% in women with 100%-199% FPL (aPR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.94) and ≥ 200% FPL (aPR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.8 to 0.88) while prevalence remained unchanged in women with < 100% FPL (aPR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.11).

In contrast to declines in breast, cervical, and prostate cancer screenings, past-year stool testing for colorectal cancer increased during the corresponding period across certain sociodemographic groups, with the increases more pronounced in Hispanic persons by 82% (from 8.3% to 15.3%; aPR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.39 to 2.37), NH Black persons by 66% (from 7.1% to 11.9%; aPR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.25 to 2.2), in persons at or below 100% of the FPL by 52% (from 7.0% to 12.1%; aPR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.15 to 2.01), and in those residing in the Northeast by 80% (from 3.7% to 6.7%; aPR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.32 to 2.46). Despite this steep increase in the Northeast, the highest prevalence of stool testing in 2021 remained in the West (17.6%).

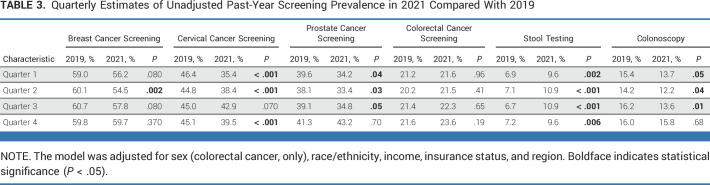

By survey quarter, declines in breast cancer screening, prostate cancer screening, and colonoscopy between 2019 and 2021 primarily occurred in the first three quarters of 2021 (Table 3). Breast cancer screening, prostate cancer screening, and colonoscopy did not statistically significantly decline or increase in quarter four. Cervical cancer screening was the only measure to decline in quarter four of 2021 versus 2019 (from 45.1% to 39.5%; P < .001). In contrast, stool testing increased across every quarter in 2021 compared with 2019.

TABLE 3.

Quarterly Estimates of Unadjusted Past-Year Screening Prevalence in 2021 Compared With 2019

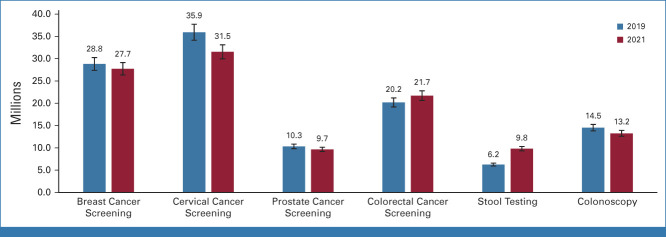

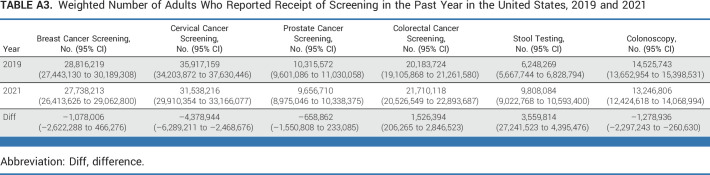

Between 2019 and 2021, the number of people who reported receipt of screening in the past year decreased from 28.8 million to 27.7 million (1.1 million fewer women in 2021; 95% CI, –2.6 million to 0.5 million) for breast cancer, from 35.9 million to 31.5 million (4.4 million fewer women in 2021; 95% CI, –6.3 million to –2.5 million) for cervical cancer, and from 10.3 million to 9.7 million (0.7 million fewer men; 95% CI, –1.6 million to 0.2 million) for prostate cancer (Fig 1 and Appendix Table A3, online only). In contrast, the number of men and women receiving colorectal cancer screening in the past year increased from 20.2 million in 2019 to 21.7 million in 2021 (1.5 million more men and women; 95% CI, 0.2 million to 2.8 million). About 3.6 million (95% CI, 2.7 million to 4.4 million) more men and women reported receipt of stool testing in the past year in 2021 than in 2019, whereas 1.3 million fewer (95% CI, –2.3 million to –0.3 million) men and women reported receipt of colonoscopy.

FIG 1.

Number of age-eligible adults who reported receipt of screening in the past year in 2019 and 2021 in the United States.

DISCUSSION

In this study of population-based nationally representative survey data, past-year screening for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer in the United States decreased anywhere from 6% to 15% between 2019 and 2021, deviating from prepandemic stable or increasing trends.14,15 In contrast, past-year colorectal cancer screening remained stable because a 44% increase in past-year stool testing offset a decline in colonoscopy prevalence. Notable jumps in stool testing occurred among Hispanic and NH Black persons and with lower socioeconomic status.

The declines in past-year screening prevalence for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer in 2021 compared with 2019, along with no increase in measures during the later quarters of 2021, suggest that screening prevalence in the United States have not fully returned, nor surpassed, the prepandemic levels after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies on the basis of claims database similarly reported declines in the screening prevalence in 2021 compared with the prepandemic levels.16,17 These declines have significant public health implications as they are expected to lead to more advanced stage cancer diagnosis in the future. For example, a recent study in New York reported an increase in proportion of stage IV lung cancer diagnoses in 2021 compared with the prepandemic period in late 2019.18 Collectively, these results reinforce the importance of continuing health system and national return to screening campaigns. The American Cancer Society and the National Football League funded Cancer Screening during COVID-19 projects to address return-to-screening in 22 community health centers.19 Another project enrolled 748 accredited cancer programs to assess cancer screening before and after the implementation of return-to-screening resources and protocols.20 Such efforts need to be extended nationwide to reach and exceed the pre-pandemic screening levels, with innovative strategies to reach all populations, but especially populations with historically low uptake of screening such as persons with low socioeconomic status.

Despite a significant decline in annual colonoscopy prevalence, consistent with recent studies largely based on claims database,16,17 past-year overall colorectal cancer screening levels remained stable during the pandemic as stool testing increased contemporaneously, similar to a previous study during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.10 The increases in stool testing were more pronounced in historically underserved populations including Hispanic and NH Black populations, and individuals with lower socioeconomic status. Historically, home-based blood stool testing has been recommended or implemented in community health centers.19,21 Studies indicate that before the pandemic, stool testing had declined and remained low in higher socioeconomic groups despite evidence showing greater screening uptake when a stool-based test is offered to these groups along with direct visualization tests,22 but it increased or remained stable among individuals with low education and income.23,24

However, among individuals who have a positive stool test, follow-up colonoscopy commonly has imposed significant out-of-pocket costs,25,26 and lack of follow-up has been a serious problem for many years,27 increasing the risk of death from colorectal cancer.28 These observations have led to the position that colorectal cancer screening with a noncolonoscopy test is incomplete if the test is positive until follow-up colonoscopy has been completed.29,30 In January 2022, the federal government issued a ruling that nongrandfathered group health plans and health insurance issuers are required to cover, without the imposition of any cost sharing, a follow-up colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization test (eg, sigmoidoscopy, computed tomography colonography).31 Of note, our findings of increased receipt of stool testing, in the face of declining receipt of colonoscopy and other screenings during the COVID-19 pandemic, underscore the need for development of homebased testing, where feasible, for other screenable cancers to maintain screening uptake during major disruption of delivery of care in doctors' office or hospitals.32

In addition to colorectal cancer screening, effective homebased testing for high-risk human papillomavirus infections has been developed for cervical cancer screening although it has yet to be recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American Cancer Society because of lack of approval by the US Food and Drug Administration.13,32-35 To make homebased testing a feasible strategy, attention to follow-up after a positive finding, availability of navigators and interpreters, and addressing other health care system, financial, and logistical barriers are needed.34

NH Asian people experienced the largest declines in breast, cervical, and prostate cancer screening. Previous studies also found similar declines for breast and cervical cancer screening, as well as for other health care services, among NH Asian individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic.10,36-38 These findings are especially concerning as cancer is the leading cause of death in both Asian American men and women, and NH Asian persons are among a racialized group with low screening uptake.39 In addition to heightened racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic, other factors that may have contributed to the steeper declines in receipt of cancer screening and other types of health services among Asian individuals include language/digital barriers and lack of trust in the health care system.36-38 Asian Americans were also more likely to report fear of COVID-19 infections.40 However, increases in stool testing offset the decline in colonoscopy among NH Asian individuals, similar to the other racial/ethnic groups, and this underscores the downstream potential for stool-based testing options as a solution for mitigating racial/ethnic disparities in receipt of screening.

Our study has several limitations. First, the NHIS had a redesign in 2019 preventing comparison with previous years of data to assess whether the decline between 2019 and 2021 is a continuation of past trends. However, this is unlikely as screening prevalence for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer increased or leveled off in prior years.14,15 Second, receipt of screening was assessed for the past year (survey questions asked have you had screening in the past year); some of the responses obtained in the first quarter of 2021 may reflect the screening experience of respondents before the closure of health facilities for primary care beginning in April 2020.41 This may have underestimated the decline in the first quarter of 2021. Third, survey respondents in 2021 had higher income than those in 2019. This may have attenuated the decline in receipt of screening for breast and cervical cancer as persons with higher socioeconomic status were more likely to receive screening.14 Fourth, because of the pandemic, the proportion of participants interviewed by telephone increased from 34.3% in 2019 to 62.8% in 2021, whereas the response rate during the corresponding period decreased from 59.1% to 50.9%.12 Although we do not know the extent and direction to which the increase in percentage of telephone interviews and lower response rate affects our estimates of changes in screening prevalence between 2019 and 2021, studies indicate that self-reported cancer screening prevalence in telephone interviews were generally found to be more accurate than in in-person interviews.42 In addition, we could not find evidence that recall bias changed during the pandemic. Finally, our analytical database (NHIS) does not allow to distinguish between screening and diagnostics.

In conclusion, in a nationally representative survey, past-year screening prevalence for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer continued to be lower in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with prepandemic levels, although prevalence in the fourth quarter of 2021 is suggestive of an uptick, or return, in breast cancer screening, prostate cancer screening, and colonoscopy. These findings reinforce the importance of strengthening return to screening campaigns for cancer prevention and control, and the major role physicians and other health care providers should play for the success of the campaigns. The large increase in stool testing is encouraging but will require increased colonoscopy follow-up of positive tests and an emphasis on annual testing. Nevertheless, this trend highlights the role of home-based testing to maintain screening levels during health care disruptions, such as in the case of increasingly common extreme weather events. Future studies should monitor the impacts of the declines in breast, cervical, and prostate cancer screening on stage at diagnosis, survival, and mortality.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Descriptions of Outcomes of Interest, US Preventive Services Task Force

TABLE A2.

Unadjusted Prevalence Ratios of Past-Year Cancer Screening in 2021 Compared With 2019

TABLE A3.

Weighted Number of Adults Who Reported Receipt of Screening in the Past Year in the United States, 2019 and 2021

Priti Bandi

Employment: Syneos Health (I)

Xuesong Han

Research Funding: AstraZeneca

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Westin at jcopodcast.libsyn.com

See accompanying Editorial, p. 4338

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jessica Star, Ahmedin Jemal

Collection and assembly of data: Jessica Star

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Cancer Screening in the United States During the Second Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Priti Bandi

Employment: Syneos Health (I)

Xuesong Han

Research Funding: AstraZeneca

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Framework for healthcare systems providing non-COVID-19 clinical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.agd.org/docs/default-source/advocacy-papers/non-covid-19-care-framework-_-cdc.pdf?sfvrsn=87302c63_0

- 2.Teglia F, Angelini M, Astolfi L, et al. : Global association of COVID-19 pandemic measures with cancer screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 8:1287-1293, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McBain RK, Cantor JH, Jena AB, et al. : Decline and rebound in routine cancer screening rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med 36:1829-1831, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song H, Bergman A, Chen AT, et al. : Disruptions in preventive care: Mammograms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Serv Res 56:95-101, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller MM, Meneveau MO, Rochman CM, et al. : Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer screening volumes and patient screening behaviors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 189:237-246, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mast C: Delayed Cancer Screenings—A Second Look. EPIC Health Research Network, 2020. https://epicresearch.org/articles/delayed-cancer-screenings-a-second-look [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprague BL, Lowry KP, Miglioretti DL, et al. : Changes in mammography use by women's characteristics during the first 5 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Natl Cancer Inst 113:1161-1167, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, et al. : Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 7:458-460, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, et al. : Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 7:878-884, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedewa SA, Star J, Bandi P, et al. : Changes in cancer screening in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2215490, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, GA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics : National Health Interview Survey, 2019 and 2021. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Preventive Services Task Force . https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. : Cancer screening test receipt—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70:29-35, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang C, Fedewa SA, Wen Y, et al. : Shared decision making and prostate-specific antigen based prostate cancer screening following the 2018 update of USPSTF screening guideline. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 24:77-80, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oakes AH, Boyce K, Patton C, et al. : Rates of routine cancer screening and diagnosis before vs after the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 9:145-146, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mafi JN, Craff M, Vangala S, et al. : Trends in US ambulatory care patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019-2021. JAMA 327:237-247, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mynard N, Saxena A, Mavracick A, et al. : Lung cancer stage shift as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns in New York City, a brief report. Clin Lung Cancer 23:e238-e242, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher-Borne M, Isher-Witt J, Comstock S, et al. : Understanding COVID-19 impact on cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer screening among federally qualified healthcare centers participating in “Back on track with screening” quality improvement projects. Prev Med 151:106681, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joung RH, Nelson H, Mullett TW, et al. : A national quality improvement study identifying and addressing cancer screening deficits due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer 128:2119-2125, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nodora JN, Gupta S, Howard N, et al. : The COVID-19 pandemic: Identifying adaptive solutions for colorectal cancer screening in underserved communities. J Natl Cancer Inst 113:962-968, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. : Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: A randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 172:575-582, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ansa BE, Lewis N, Hoffman Z, et al. : Evaluation of blood stool test utilization for colorectal cancer screening in Georgia, USA. Healthcare (Basel) 9:569, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandi P, Cokkinides V, Smith RA, et al. : Trends in colorectal cancer screening with home-based fecal occult blood tests in adults ages 50 to 64 years, 2000-2008. Cancer 118:5092-5099, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fendrick AM, Fisher DA, Saoud L, et al. : Impact of patient adherence to stool-based colorectal cancer screening and colonoscopy following a positive test on clinical outcomes. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 14:845-850, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mark Fendrick A, Borah BJ, Burak Ozbay A, et al. : Life-years gained resulting from screening colonoscopy compared with follow-up colonoscopy after a positive stool-based colorectal screening test. Prev Med Rep 26:101701, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper GS, Grimes A, Werner J, et al. : Barriers to follow-up colonoscopy after positive FIT or multitarget stool DNA testing. J Am Board Fam Med 34:61-69, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zorzi M, Battagello J, Selby K, et al. : Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut 71:561-567, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. : Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 68:250-281, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. : Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 325:1965-1977, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Labor : FAQs About Affordable Care Act Implementation Part 51, Families First Coronavirus Response Act and Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act Implementation. Washington, DC, Department of Labor, 2022, pp 16 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorin SNS, Jimbo M, Heizelman R, et al. : The future of cancer screening after COVID-19 may be at home [published correction appears in Cancer. 2021 Nov 15;127(22):4315]. Cancer 127:498-503, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al. : Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: Updated meta-analyses. BMJ 363:k4823, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuzzell LN, Perkins RB, Christy SM, et al. : Cervical cancer screening in the United States: Challenges and potential solutions for underscreened groups. Prev Med 144:106400, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. : Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 70:321-346, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang D, Li G, Shi L, et al. : Association between racial discrimination and delayed or forgone care amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med 162:107153, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahase E: Covid-19: Asian patients experienced largest fall in elective care, report finds. BMJ 379:o2644, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Shi L, Han X, et al. : Disparities in telehealth utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a nationally representative survey in the United States. J Telemed Telecare 10.1177/1357633X211051677 [epub ahead of print on October 11, 2021] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee RJ, Madan RA, Kim J, et al. : Disparities in cancer care and the Asian American population. Oncologist 26:453-460, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niño M, Harris C, Drawve G, et al. : Race and ethnicity, gender, and age on perceived threats and fear of COVID-19: Evidence from two national data sources. SSM Popul Health 13:100717, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services : Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- 42.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, et al. : Accuracy of self-reported cancer-screening histories: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:748-757, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]