Abstract

Vaccine trials were undertaken to determine whether the Fel-O-Vax® FIV, a commercial dual-subtype (subtypes A and D) feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) vaccine, is effective against a subtype B FIV isolate. Current results demonstrate the Fel-O-Vax FIV to be effective against a subtype B virus, a subtype reported to be the most common in the USA.

The development of effective vaccines against acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) lentiviruses such as HIV-1 and FIV is difficult to achieve. This may be due to multiple subtypes and diversity of strains within each subtype that are present worldwide. Although a number of single-strain FIV vaccines were effective against homologous and closely-related heterologous FIV challenges, these vaccines failed to confer protection against distinctly heterologous FIV strains, especially from different subtypes (Uhl et al 2002). As a result, an inactivated dual-subtype FIV vaccine, consisting of subtype A (FIV-Petaluma, FIVPet) and D (FIV-Shizuoka, FIVShi) strains, was developed to broaden vaccine immunity against heterologous subtype viruses (Pu et al 2001). Unlike the single-strain FIV vaccines, the dual-subtype vaccine was effective against a heterologous subtype B envelope strain (FIV-Bangston, FIVBang) in addition to vaccine strains. The in vivo-derived challenge inocula used in these studies were obtained directly from infected cats, simulating natural exposure to contaminated blood (Uhl et al 2002). In vivo-derived inoculum is considered to be more difficult to protect against than in vitro-derived culture inoculum (Hesselink et al 1999, Uhl et al 2002). Subtype B is considered to be the predominant subtype in the USA, followed by subtype A (Bachmann et al 1997, Kahler 2002). Thus, the protection observed with dual-subtype FIV vaccine is clinically relevant.

A commercial dual-subtype FIV vaccine, Fel-O-Vax FIV (Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA), was USDA-approved in April 2002 and released for sale in July 2002 (Uhl et al 2002). This vaccine was approved based on two 1-year efficacy studies against a subtype A challenge virus that was 9% and 20% different from the envelope sequences of the vaccine strains (FDAH, personal communication). The dual-subtype FIV vaccine previously reported to be effective against subtype B envelope strain (Pu et al 2001) is the prototype to the Fel-O-Vax FIV. Although both vaccines contain only subtypes A (FIVPet) and D (FIVShi), these vaccines differ in composition (Omori et al 2004). Consequently, it was unknown whether the commercial vaccine would protect cats against distinctly heterologous challenges to the level demonstrated by the prototype dual-subtype vaccine. The current studies were undertaken to determine whether the Fel-O-Vax FIV can confer cross-protection against a challenge strain from a subtype different than the vaccine subtypes.

The Fel-O-Vax FIV vaccine purchased from the University of Florida Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, was tested against a virulent subtype B strain (FIV-Florida cat 1, FIVFC1) isolated from a pet cat living in Florida. FIVFC1 inoculum consisted of pooled peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from three specific pathogen-free cats infected with blood from an FIVFC1-infected cat. The FIVFC1-infected PBMC were isolated from the blood by density-gradient centrifugation (Lymphocyte Separation Media, Cellgro, Mediatech Inc., Herdon, VA) and cryopreserved (10×106 cells/vial). The inoculum has been titrated in vivo using groups of two to three cats per inoculum dose (1×105, 2.5×105, 5×105, 1×106 cells/dose). Using FIVUK8 and FIVPet as high and low virulence strains, respectively (Hosie et al 2000), a preliminary study was conducted to evaluate the virulence of FIVFC1 based on virus load. Twenty- to 22-week-old specific pathogen-free cats were inoculated with 25 CID50 of in vivo-derived inoculum of each strain. FIV load was determined by semiquantitative virus isolation of PBMC from the infected cats at 6 weeks post inoculation (wpi) (Yamamoto et al 1998). The FIV load is shown as number (10-fold increase from 50 to 5×105 cells) of PBMC needed to detect virus. In this study, detection of FIVFC1 and FIVUK8 required only 500 cells, in contrast, detection of FIVPet required 50,000 cells. This preliminary finding suggests that FIVFC1 is more virulent than FIVPet and comparable in virulence to FIVUK8. Two separate studies were conducted using specific pathogen-free cats immunized subcutaneously with Fel-O-Vax FIV three times at 3-week intervals as recommended by the manufacturer. Age-matched specific pathogen-free cats served as unchallenged controls for each study. Study 1 consisted of 10 cats randomized into three groups: group 1 (n=4) received Fel-O-Vax FIV, groups 2 (n=2) and 3 (n=4) received uninfected vaccine cells or phosphate buffered saline, respectively. Uninfected vaccine cells are inactivated FeT-J cells, an uninfected feline T-cell line, which is related to both FIVPet-infected and FIVShi-infected cell lines used in the Fel-O-Vax FIV vaccine (Omori et al 2004). Although FD-1 adjuvant was available in our previous studies (Omori et al 2004), current study used Ribi adjuvant (Corixa, Hamilton, MT) due to recent Fort Dodge Animal Health's decision not to release any more FD-1 adjuvant for research use. Three weeks after immunizations, the cats were intravenously challenged with an in vivo-derived FIVFC1 at 15 median cat infectious doses (CID50). Intravenous challenge simulates natural FIV transmission via biting and fighting (scratching) by infected cats (Uhl et al 2002). Biting and fighting usually results in ruptured vessels causing the virus to enter directly into the blood. After the challenge, these vaccinated cats have remained FIV negative, with normal CD4 counts and normal CD4/CD8 ratios (Pu et al 1999) for 1 year after first immunization, while exhibiting full protection against FIVFC1 challenge (Table 1). The monitoring for viral infection included FIV isolation of PBMC, lymph node cells, and bone marrow cells using a co-culture amplification method with viral detection based on both viral reverse transcriptase and proviral PCR (Pu et al 2001). In contrast, all cats in groups 2 and 3 were infected by 6 wpi with significantly decreased CD4 counts and CD4/CD8 ratios following infection.

Table 1.

Fel-O-Vax FIV vaccine efficacy against virulent heterologous FIVFC1 challenge (15 CID50)

| Study group | Vaccine immunogen * | Adjuvant * | Pre-challenge | 16/20 wpi † | 43 wpi † | Number protected/total (% protection) † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | CD4/CD8 | CD4 | CD4/CD8 | CD4 | CD4/CD8 | ||||

| 1-1 | Fel-O-Vax FIV | FD-1 | 2.63±0.48 | 3.35±0.75 | 2.01±0.89 | 2.33±0.24 | 1.25±0.27 | 1.65±0.14 | 4/4 (100%) |

| 1-2 | Uninfected cells | Ribi | 2.23±0.71 | 3.28±0.25 | 1.35±0.59 † | 1.32±0.11 † | NA | NA | 0/2 (0%) |

| 1-3 | None | PBS | 2.50±1.19 | 3.01±1.08 | 0.72±0.35 § | 0.77±0.39 § | NA | NA | 0/4 (0%) |

| 1-4 ‡ | None (age-matched) | None | 2.51±1.15 | 3.26±0.25 | 2.09±0.77 | 2.47±0.58 | 1.21±0.49 | 1.70±0.31 | Unchallenged |

| 2-1 | Fel-O-Vax FIV | FD-1 | 2.91±1.00 | 3.19±0.56 | 2.76±0.45 | 2.59±0.67 | NA | NA | 4/4 (100%) |

| 2-2 | None | PBS | 2.75±0.67 | 3.15±1.02 | 2.00±0.77 | 1.13±0.29§ | NA | NA | 0/3 (0%) |

| 2-3 ‡ | None (age-matched) | None | 2.82±0.92 | 3.15±0.53 | 2.63±0.71 | 2.56±0.29 | NA | NA | Unchallenged |

| Study 1 § | Study 2 § | ||||||||

| 16 wpi CD4 group 3 versus group 4 | P=0.040 | 20 wpi CD4/CD8 group 1 versus group 2 | P=0.017 | ||||||

| 16 wpi CD4/CD8 group 1 versus group 3 | P=0.012 | 20 wpi CD4/CD8 group 2 versus group 3 | P=0.002 | ||||||

| 16 wpi CD4/CD8 group 3 versus group 4 | P=0.017 | ||||||||

*The commercial vaccine Fel-O-Vax FIV or placebo consisting of PBS were immunized subcutaneously at 3-week intervals and challenged intravenously with FIVFC1 3 weeks after the last immunization. The specific pathogen-free cats in group 2 of study 1 were immunized with uninfected cells (2×107 cells/dose) mixed in Ribi adjuvant and challenged at the same time. The first immunization in studies 1 and 2 was given at 10 weeks of age and 12–14 weeks of age, respectively.

†Cats were tested for FIV infection by virus isolation performed on PBMC (4, 6, 9, 12, 16, 20 wpi), lymph nodes (20 wpi), and bone marrow cells (20 wpi) and the co-cultures were monitored for viral RT and proviral PCR as previously described (Pu et al 2001). Protected/vaccinated cats from study 1 were monitored for over 1 year post first immunization (47 wpi) and were negative for FIV by virus isolation performed on PBMC (24, 43, 47 wpi), lymph node cells (47 wpi) and bone marrow cells (47 wpi). Cats were monitored for CD4 counts and CD4/CD8 ratio at −2, 4, 12, 16, and 43 wpi in study 1 and at −2, 5, 7, 9, 12, 16, and 20 wpi in study 2 as previously described (Pu et al 1999). CD4 and CD4/CD8 values for one of the cats from group 2 of study 1 were from blood collected at 12 wpi instead of 16 wpi because the amount of blood collected from this cat at 16 wpi was not enough to perform both virus isolation and CD4/CD8 analysis. As a result, the average CD4 and CD4/CD8 ratio for group 2 at 16 wpi may be higher than what may have been if the blood from both cats were from 16 wpi. All FIV-positive cats were euthanased at 20 wpi and were not available for monitoring beyond 20 wpi (NA). The protected/vaccinated cats from studies 1 and 2 are currently at 47 wpi and 20 wpi, respectively.

‡Four age-matched specific pathogen-free cats for each study were maintained for monitoring of CD4 counts and CD4/CD8 ratios.

Those comparisons with statistical significant difference (P<0.05) are shown. Group 2 was not compared due to small sample number (n=2). The statistical significance was determined by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and paired or two-sample equal variance T-test using SAS program, version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

In study 2, seven specific pathogen-free cats were divided into group 1 (n=4) immunized with Fel-O-Vax FIV and group 2 (n=3) immunized with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). All cats were challenged using the same inoculum, dose and schedule as in study 1. All Fel-O-Vax FIV vaccinated cats were protected with normal CD4 counts and CD4/CD8 ratios throughout the 18 wpi of the study, while all PBS-immunized cats were infected by 9 wpi with substantial decreases in CD4 counts and CD4/CD8 ratios (Table 1).

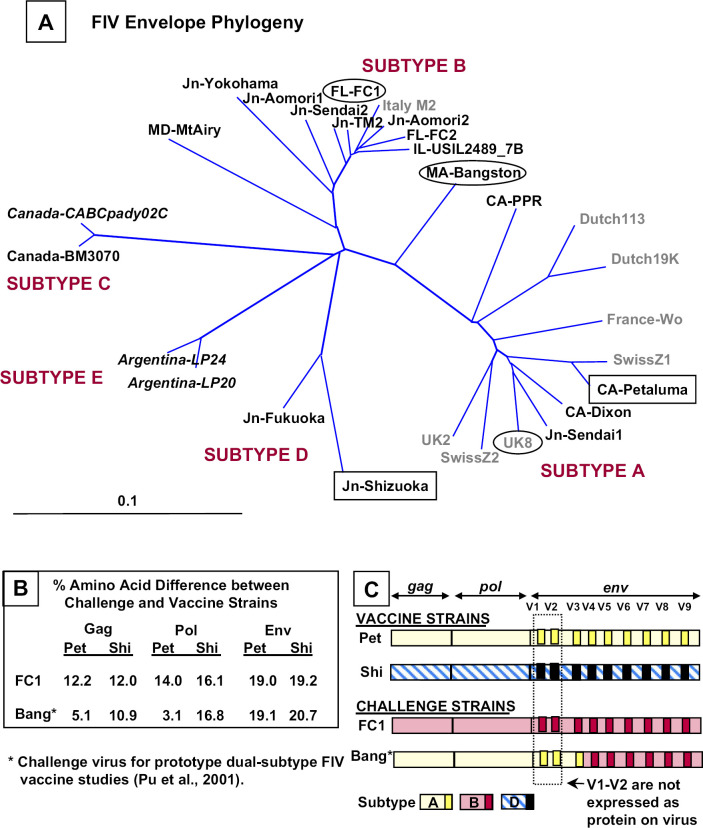

These are the first studies to demonstrate protection conferred by a commercial dual-subtype A and D vaccine, Fel-O-Vax FIV, against a virulent subtype B strain (FIVFC1). As illustrated by our phylogenetic tree (Fig 1a), the challenge strain FIVFC1 differs significantly from both vaccine strains (12.0 and 12.2% Gag; 14.0 and 16.1% Pol; 19.0 and 19.2% Env) (Fig 1b). Our FIVFC1 inoculum consisted of a pooled PBMC from specific pathogen-free cats infected with blood from an FIVFC1-infected cat. Hence, the subtype B inoculum derived from infected cats simulated the natural inoculum compared to that obtained from culture fluids (Hesselink et al 1999, Uhl et al 2002). FIVFC1-infected cats had depleted CD4 counts and decreased CD4/CD8 ratios within 20 wpi, and maintained a high virus load throughout the trial. In contrast, the vaccinated cats maintained normal CD4 counts and CD4/CD8 ratios. Thus, the results obtained from these studies also show protection based on the CD4 and CD8 profiles.

Fig 1.

The phylogenetic tree distribution (panel A), amino acid comparison (panel B), and recombination analysis (panel C) of the vaccine viruses and challenge virus used in current studies 1 and 2, and the virus (FIVBang) reported for prototype dual-subtype FIV vaccine studies (Pu et al 2001). The two vaccine viruses (boxes) and two challenge viruses (ovals), along with known FIV strains, are displayed in a phylogenetic tree of the FIV envelope (env). An unrooted phylogenetic tree was created using the BLOSUM matrix and neighbor-joining algorithm based on the Kimura two-parameter correction (Saitou and Nei 1987, Kimura 1980). Support at each internal node was assessed using 1000 bootstrap samplings and each tree was visualized using Tree View (Felsenstein 1989, Page 1996). All full-length isolates from NCBI data bank (Accession numbers M36968, X60725, M73964, L06312, X57002, M25381, L00607, D37813, X69496, X57001, X69494, D37811, D37815, AF474246, AF452126, D37812, D37816, D37814, E03581, AY621093, D37817, AY621094, U11820, AY620002) have been used with the exception of those based on partial sequences, which are designated in italics (CaBCpady02C, LP-24, LP-20, M2) (Accession numbers U02392, AB027304, AB027302, X69501). Isolates from Japan are designated with Jn, and isolates from USA are designated with the state abbreviation followed by the name of the virus. The amino acid (aa) sequence comparisons (panel B) between the vaccine and challenge strains used in our studies further demonstrate that both vaccine strains (FIVPet and FIVShi) had the greatest % aa difference from subtype B FIVFC1 at all viral proteins (Gag, Pol, Env) analyzed. The recombination analysis (panel C) of structural and polymerase genes of the vaccine and challenge strains was based on phylogenetic tree distributions of the FIV group-specific antigen (gag, tree not shown), FIV polymerase (pol, tree not shown), and FIV env (panel A). FIVBang is a recombinant of subtypes A and B, and FIVFC1 belongs to subtype B at gag, pol and env.

The Fel-O-Vax FIV was initially reported to confer 67 (18 of 27 cats) to 84% (21 of 25 cats) protection against an intramuscular heterologous subtype A FIV challenge in two USDA trials. This challenge inoculum caused an infection rate of 74–90% in unvaccinated control cats in these trials (Uhl et al 2002). Based on our findings and the FDAH data from the USDA application trials, the Fel-O-Vax FIV appeared to be as effective as the prototype dual-subtype FIV vaccine for protecting cats against homologous (FIVPet and FIVShi) and heterologous (FIVBang) FIV strains (Pu et al 2001). FIVBang, a recombinant of subtypes A gag/pol/env(V1-V3) and B env(V4-V9) (Fig 1a and c), is closely related to FIVPet (subtype A vaccine strain) at Gag and Pol (Fig 1b). As a result of this similarity at the Gag and Pol regions, the protection conferred by the prototype dual-subtype vaccine against recombinant FIVBang, may result from the immunity induced to these regions. In this trial, 100% (8 of 8) of the vaccinated animals were protected, whereas 0% (0 of 7) of the placebo (PBS)-immunized cats were protected against the heterologous subtype B virus (FIVFC1). The vaccine protection observed with Fel-O-Vax FIV against non-recombinant subtype B strain is a clear demonstration that a dual-subtype vaccine approach can induce broad protective immunity and confer protection against heterologous subtype challenge.

Recent results from a veterinary company suggest enhancement of experimental infection in unprotected cats vaccinated with Fel-O-Vax FIV (Berlinski et al 2003). Vaccine-induced enhancement was reported with experimental single-subtype vaccines containing FIV strain antigens other than FIVPet or FIVShi (Hosie et al 1992, Karlas et al 1999). However, vaccine-induced enhancement has not been reported with single-subtype FIVPet or FIVShi vaccines (Hosie et al 1992, Elyar et al 1997, Karlas et al 1999, Uhl et al 2002), or prototype dual-subtype FIV vaccine (Pu et al 2001). In fact, unprotected, single-subtype FIVPet-vaccinated cats upon FIVUK8 challenge, had lower virus loads than unvaccinated, challenged cats and were protected against loss of CD4+ T cells (Hosie et al 2000). In our studies, all Fel-O-Vax FIV vaccinated cats were fully protected resulting in no unprotected/vaccinated cats in which to detect potential vaccine enhancement. Furthermore, cats immunized with uninfected vaccine cells (2×107 cells/dose) showed no enhancement of FIV infection. Although Ribi adjuvant was used for uninfected vaccine cell immunization in the current study, our previous studies have shown that the uninfected vaccine cell immunization with FD-1 adjuvant had no protective effects against challenge with different FIV strain (Pu et al 2000). These observations are important because Fel-O-Vax FIV is a mixture of inactivated infected cells (1.5–2.5×107 provirus-positive cells/dose) and whole viruses (R. Pu, M. Arai, J.K. Yamamoto, personal communication).

The concerns raised by some veterinarians on whether the Fel-O-Vax FIV is efficacious against heterologous subtype B strains is based on the concept that the vaccine is only effective against homologous subtype strains that comprise the vaccine (Kahler 2002, Ford 2003). Further, some USA veterinarians assert that as subtype B is the predominant American subtype, the dual-subtype FIVPet/Shi vaccine is inappropriate for use in the USA. This perception was reinforced by the results of earlier single-strain vaccine trials (Johnson et al 1994, Elyar et al 1997, Uhl et al 2002). The 100% protection with Fel-O-Vax FIV (subtype A and D vaccine) against subtype B virus suggests that subtype-specificity may not be a factor in vaccine efficacy. However, it is still possible that by combining two subtype vaccine strains, Fel-O-Vax FIV may be broadening vaccine immunity against non-vaccine subtype strains similar to that reported for the prototype dual-subtype FIV vaccine (Pu et al 2001). Nevertheless, these studies clearly show that a dual-subtype FIV vaccine can induce broad prophylactic immunity and confer protection against a heterologous subtype challenge.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Dr Terrell Heaton-Jones for editorial assistance. This work was supported by NIH R01 AI30904 and JKY Miscellaneous Donors Fund. J.K. Yamamoto is the inventor of record on a University of Florida held patent and may be entitled to royalties from companies that are developing commercial products that are related to the research described in this paper.

References

- Bachmann M.H., Mathiason-Dubard C., Learn G.H., Rodrigo A.G., Sodora D.L., Mazzetti P., Hoover E.A., Mullins J.I. Genetic diversity of feline immunodeficiency virus: dual infection, recombination, and indistinct evolutionary rates among envelope sequence clades, Journal of Virology 71, 1997, 4241–4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlinski PJ, Gibson JK, Forester NJ, Martin S. (2003) Further investigation into the increased susceptibility of cats to feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) after vaccination with parenteral vaccines. In: 21st Annual American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine's Forum, Charlotte, North Carolina, June 4–8, 2003, Abstract #11.

- Elyar J.S., Tellier M.C., Soos J.M., Yamamoto J.K. Perspectives on FIV vaccine development, Vaccine 15, 1997, 1437–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP-phylogeny inference package, Cladistics 5, 1989, 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ford R.B. Sounding board. Response from the author, North American Veterinary Conference Clinician's Brief 2, 2003, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselink W., Sondermeijer P., Pouwels H., Verblakt E., Dhore C. Vaccination of cats against feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV): a matter of challenge, Veterinary Microbiology 69, 1999, 109–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie M.J., Dunsford T., Klein D., Willett B.J., Cannon C., Osborne R., MacDonald J., Spibey N., Mackay N., Jarrett O., Neil J.C. Vaccination with inactivated virus but not viral DNA reduces virus load following challenge with a heterologous and virulent isolate of feline immunodeficiency virus, Journal of Virology 74, 2000, 9403–9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie M.J., Osborne R., Reid G., Neil J.C., Jarrett O. Enhancement after feline immunodeficiency virus vaccination, Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 35, 1992, 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C.M., Torres B.A., Koyama H., Yamamoto J.K. FIV as a model for AIDS vaccination, AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 10, 1994, 225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler S.C. News. Deluge of questions prompts AAFP to develop FIV Vaccine Brief, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 221, 2002, 1231–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlas J.A., Siebelink K.H.J., van Peer M.A., Huisman W., Cuisinier A.M., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Osterhaus A.D.M.E. Vaccination with experimental feline immunodeficiency virus vaccines, based on autologous infected cells, elicits enhancement of homologous challenge infection, Journal of General Virology 80, 1999, 761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitution through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences, Journal of Molecular Evolution 16, 1980, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori M, Pu R, Tanabe T, Hou W, Coleman JK, Arai M, Yamamoto JK. (2004) Cellular immune responses to feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) induced by dual subtype FIV vaccine. Vaccine, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Page R.D.M. Treeview: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers, Computational Applied Bioscience 12, 1996, 357–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu R., Coleman J., Omori M., Hohdatsu T., Arai M., Huang C., Tanabe T., Yamamoto J.K. Dual-subtype FIV vaccine protects cats against in vivo swarms of both homologous and heterologous subtype FIV isolates, AIDS 15, 2001, 1225–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu R., Omori M., Okada S., Rine S.L., Lewis B.A., Lipton E., Yamamoto J.K. MHC-restricted protection of cats against FIV infection by adoptive transfer of immune cells from FIV-vaccinated donors, Cellular Immunology 198, 1999, 30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees, Molecular Biology and Evolution 4, 1987, 406–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl E.W., Heaton-Jones T.G., Pu R., Yamamoto J.K. FIV vaccine development and its importance to veterinary and human medicine: a review, Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 90, 2002, 113–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto J.K., Pu R., Maki A., Pollock D., Irausquin R., Bova F.J., Fox L.E., Homer B.L., Gengozian N. Feline bone marrow transplantation: its use in FIV-infected cats, Vaccine 65, 1998, 323–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]