Abstract

Background

Understanding how participation is changing across domains of physical activity is important for monitoring progress and informing promotion efforts. We examined changes in physical activity participation in NHANES 2007/2008—2017/2018.

Methods

The prevalence of inactivity, insufficient activity, and meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline in multi-domain physical activity and each domain (leisure-time, occupational/household, transportation) was estimated for each cycle and stratified by selected characteristics. We tested trends over time and overall changes (2017/2018 vs. 2007/2008).

Results

For multi-domain physical activity, the prevalence of inactivity decreased linearly; meeting the aerobic guideline increased nonmonotonically, and the 2017/2018 prevalence (68.1%) was higher than 2007/2008 (64.1%). Similar findings were observed for adults aged ≥65 years, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, high school graduates, and adults with obesity. Domain-specific results varied, but decreasing trends in inactivity and increasing trends in meeting the guideline were consistently observed across subgroups for occupational/household activity. Meeting the guideline through transportation activity was rare.

Conclusions

Increases in meeting the guideline and decreases in inactivity in multi-domain and are encouraging results, especially among subgroups historically reporting low activity participation. Activity promotion efforts are important to maintain progress, and the transportation domain may be an underutilized source of physical activity.

Introduction

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, second edition provides evidence-based recommendations for physical activity participation.1 For adults, the Guidelines recommend moving more and sitting less throughout the day and acknowledge that some activity is better than none. For substantial health benefits, adults should do at least 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes to 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity (henceforth, moderate-intensity equivalent activity), preferably spread throughout the week. Additional health benefits can be achieved with participation beyond 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity equivalent activity.

The recommendations in the Guidelines suggest several levels of aerobic physical activity participation are important for public health monitoring. First, inactivity, or the lack of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity, impairs health and is to be avoided. Second, insufficient activity (doing some moderate intensity equivalent physical activity, but less than 150 minutes per week) provides some health benefits compared to inactivity, but not as many health benefits as meeting the aerobic guideline. Third, meeting the minimum aerobic guideline of at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity equivalent aerobic activity provides substantial health benefits compared to inactivity. Because the health effects differ by level of participation1, documenting how participation is changing among these categories is important for understanding the impact of physical activity levels on population health.

The Guidelines define aerobic activity as “physical activities in which people move their large muscles in a rhythmic manner for a sustained period of time”1 and include running, brisk walking, cycling, dancing, and swimming as example aerobic activities.1 Notably, the Guidelines state the purpose of the aerobic activity does not matter; people with physically active occupations or those who walk or bicycle for transportation can count those activities towards their weekly total, as long as the activities are of at least moderate intensity (e.g., walking should be brisk).1 The purpose of physical activity is usually classified into four domains: leisure, occupational, household, and transportation (i.e. domain-specific physical activity).2 Though activity in any domain counts towards meeting guidelines, public health monitoring of physical activity participation often focuses on leisure-time activities.3–5 Expanding surveillance to include all domains (i.e. multi-domain physical activity) may be important for accurate assessment of meeting the aerobic Guidelines.6

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is unique among U.S. public health surveillance systems in consistently including a multi-domain assessment of aerobic physical activity participation since 2007/2008.7 A recent report by Du, et al., examined multi-domain physical activity among adults in NHANES from 2007/2008 to 2015/2016 and revealed no statistically significant increases in meeting the aerobic guideline overall, but subgroup increases among women, non-Hispanic Blacks, and adults of normal weight or with obesity.8 At least two important questions remain unanswered regarding multi-domain aerobic physical activity participation among adults. First, a new cycle (2017/2018) of NHANES data is available; will the new cycle alter previous findings? Second, trend estimates for inactivity and insufficient activity have not been published; is participation changing in these categories? Answering these questions will indicate if and how multi-domain aerobic physical activity is changing among U.S. adults.

In addition to multi-domain aerobic physical activity, understanding how domain-specific activity is changing is also important. Low participation in one domain may suggest an opportunity to increase participation through targeted strategies. For example, the Guide to Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends creating activity-friendly routes to everyday destinations by combining improved pedestrian or bicycle transportation infrastructure with land use and environmental design interventions.9 Linking destinations could impact transportation-related physical activity to a greater degree than activity in other domains. Further, patterns of participation by subgroup may differ across domains.6,10 For example, recent reports suggest differences in physical activity participation across levels of educational attainment are wider when leisure-time physical activity is considered in isolation than when combined with other domains.6,10 Understanding how participation in each domain is changing over time is therefore important to identify opportunities for intervention and to determine if disparities are changing.

The purpose of this paper is to update and address gaps in our understanding of physical activity participation across domains among U.S. adults by answering two questions. First, when examining multi-domain physical activity, how has the prevalence of inactivity, insufficient activity, and meeting the aerobic guideline changed from 2007/2008 to 2017/2018 overall and by selected subgroups? Second, when examining domain-specific physical activity, how has the prevalence of inactivity, insufficient activity, and meeting the aerobic guideline changed from 2007/2008 to 2017/2018 overall and by selected subgroups?

Methods

Data source

Detailed methods about the NHANES design, sampling, and data collection are available from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)7 and are summarized here. NHANES is an ongoing, in-person cross-sectional survey designed to be representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population. Though data collection is continuous, data are released in 2-year cycles. This analysis covers the period of consistent multi-domain physical activity assessment spanning six two-year cycles beginning 2007/2008 through the most recently released 2017/2018 cycle. Publicly available data from these years were downloaded from the NCHS website.7

Physical activity assessment

Participants reported typical-week aerobic physical activity participation using items adapted from the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire.11 Activity was assessed in three sections: combined occupational and household activity, transportation-related walking and bicycling, and leisure time physical activity (Table 1). Occupational/household and leisure-time activity was further divided into moderate- and vigorous-intensity, while transportation was classified as moderate-intensity only. When a participant answered “yes” to a prompt, they were asked about the frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per day) for that domain and intensity combination. Weekly minutes were calculated as frequency times duration, and vigorous minutes were doubled to yield moderate-intensity equivalent minutes.1 Participants were classified into participation categories based on moderate-intensity equivalent minutes per week: inactive (no reported activity of at least 10 continuous minutes), insufficiently active (some activity, but not enough to meet the guideline), and meeting the aerobic guideline (≥150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity equivalent activity). We repeated this classification four times: once using moderate-intensity equivalent minutes from all domains (multi-domain activity); and three additional times analyzing domain-specific activity (leisure-time only, occupational /household only, and transportation only). NHANES only assessed aerobic physical activity during this period, so while we acknowledge the importance of muscle-strengthening activity1, this analysis is limited to aerobic activity only.

Table 1:

Physical activity assessment prompts* in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007/2008 – 2017/2018

| Order | Domain(s) | Intensity Level | Prompt |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n/a | n/a | Next I am going to ask you about the time you spend doing different types of physical activity in a typical week. |

| 2 | Combined Occupational / Household | Vigorous | Think first about the time you spend doing work. Think of work as the things that you have to do such as paid or unpaid work, studying or training, household chores, and yard work. Does your work involve vigorous-intensity activity that causes large increases in breathing or heart rate like carrying or lifting heavy loads, digging or construction work for at least 10 minutes continuously? |

| 3 | Combined Occupational / Household | Moderate | Does your work involve moderate-intensity activity that causes small increases in breathing or heart rate such as brisk walking or carrying light loads for at least 10 minutes continuously? |

| 4 | Transportation | Moderate† | The next questions exclude the physical activity of work that you have already mentioned. Now I would like to ask you about the usual way you travel to and from places. For example to work, for shopping, to school. In a typical week, do you walk or use a bicycle for at least 10 minutes continuously to get to and from places? |

| 5 | Leisure-time | Vigorous | The next questions exclude the work and transportation activities that you have already mentioned. Now I would like to ask you about sports, fitness and recreational activities. In a typical week, do you do any vigorous-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities that cause large increases in breathing or heart rate like running or basketball for at least 10 minutes continuously? |

| 6 | Leisure-time | Moderate | In a typical week, do you do any moderate-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities that cause a small increase in breathing or heart rate such as brisk walking, bicycling, swimming, or golf for at least 10 minutes continuously? |

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Only the prompts are presented here. When participants answer in the affirmative, follow-up questions assess the usual frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per day) of participation for each domain/intensity.

All transportation-related activity is assumed to be of moderate-intensity in NHANES

Stratifying Variables

Participants self-reported their gender (male, female), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years), and educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college or an associate’s degree, and a college degree or higher). Participants reported their racial and ethnic group (non-Hispanic White; non-Hispanic Black; Mexican-American; other Hispanic; and non-Hispanic other race, including multi-racial [NHANES Variable RIDRETH1]); Mexican-American and other Hispanic were collapsed into a single Hispanic category. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms) / height squared (meters2), where weight and height were obtained from measurements taken in NHANES mobile examination centers.7 BMI was classified as normal underweight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 – <30 kg/m2), or having obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).12

Analytic sample

The 2007/2008 to 2017/2018 NHANES included 36,580 adults aged 18 years or older. Sample sizes ranged from a low of 5,856 in 2017/2018 to a high of 6,527 in 2009/2010. Physical activity data were complete for 36,418 (99.6%) respondents. An additional 49 respondents (0.1%) were missing data on educational attainment and 1,917 (5.3%) were missing BMI; results stratified by education or BMI omit these respondents.

Statistical analysis

For each NHANES cycle, we estimated the proportion of adults who were inactive, insufficiently active, and met the aerobic guideline in multi-domain activity; estimates were age-standardized to the 2000 US adult population.13 These estimates were then stratified by the covariates described above. We examined changes over time in two ways: first, we tested for linear and higher-order trends over time using age-adjusted logistic regression models with orthogonal polynomial contrasts. Second, we calculated the overall change in prevalence over this period as prevalence2017/2018 – prevalence2007/2008, expressed as percentage point differences, and tested for difference from zero using adjusted Wald tests. We repeated the above steps three additional times, analyzing leisure time activity, occupational/household activity, and transportation activity in isolation. The domain-specific classification into categories of inactivity, insufficient activity, and meeting the aerobic guideline ignores any activity reported in other domains.

All analyses were performed in Stata version 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). We followed all NHANES analytic guidelines7, including using interview sampling weights when all data were from interviews, and using Mobile Examination Center weights when including BMI.

Results

Multi-domain activity

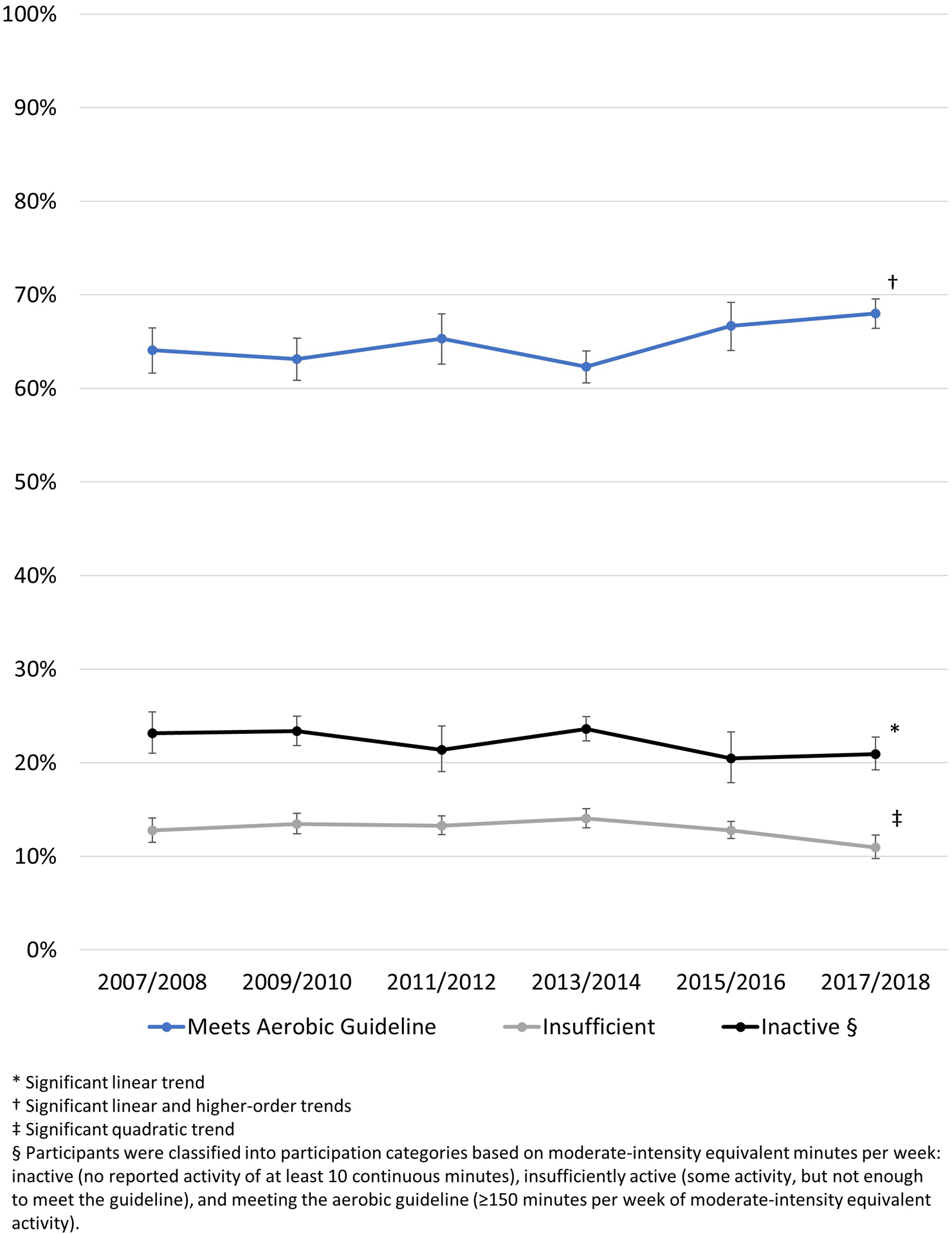

When all domains were analyzed together, there was a significant negative linear trend in the prevalence of multi-domain inactivity over the period between 2007/2008 and 2017/2018 (Figure 1). The prevalence of insufficient multi-domain activity exhibited a significant negative quadratic trend without an accompanying significant linear trend. The prevalence of meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline increased nonmonotonically, with significant positive linear and quadratic trends. Throughout the study period, changes in inactivity from one cycle to the next tended to be of similar magnitude to, but in opposite direction from corresponding changes in meeting the aerobic guideline.

Figure 1a:

Age-adjusted prevalence of three levels of multi-domain physical activity participation among U.S. adults, NHANES 2007–2018

Despite the linear decline in inactivity, there was no overall change in the prevalence of multi-domain inactivity when comparing 2007/2008 to 2017/2018 among the sample of all adults. The prevalence of multi-domain inactivity was significantly lower in 2017/2018 compared to 2007/2008 among adults aged 65 years or older, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, adults with a high school education, and adults with obesity (Table 2). These groups also exhibited significant negative linear trends, though the trends were nonmonotonic among non-Hispanic Blacks and adults with obesity. The prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline was significantly higher in 2017/2018 compared to 2007/2008 among adults overall and among women, adults aged 18–24 or ≥65 years, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, adults with a high school education, normal or underweight adults, and adults with obesity. All of these groups plus adults aged 25–34 years exhibited significant positive linear trends, though trends were nonmonotonic among adults with a high-school education and adults with obesity. Men, non-Hispanic Whites, and adults with some college education exhibited positive quadratic trends without accompanying significant linear trends. Estimates of multi-domain insufficient activity participation by subgroup are available in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 2:

Prevalence of inactivity and meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline using all domains among adults, NHANES 2007/2008 and 2017/2018

| Inactive | Meets Aerobic Guideline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | |||||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† |

| Overall | 23.1 | 21.0–25.4 | 20.9 | 19.2–22.7 | −2.2 | L | 64.1 | 61.6–66.5 | 68.1 | 66.5–69.6 | 4.0* | L, Q |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 18.2 | 15.9–20.8 | 15.9 | 14.2–17.7 | −2.3 | 72.0 | 69.2–74.6 | 75.0 | 72.5–77.2 | 3.0 | Q | |

| Female | 27.6 | 24.9–30.5 | 25.6 | 23.3–28.0 | −2.1 | 56.9 | 53.9–59.8 | 61.8 | 59.8–63.8 | 5.0* | L | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 14.2 | 11.6–17.2 | 11.7 | 9.2–14.9 | −2.4 | 74.7 | 70.1–78.8 | 82.3 | 78.0–85.9 | 7.6* | L | |

| 25–34 | 15.0 | 12.4–18.1 | 14.4 | 12.3–16.9 | −0.6 | 75.6 | 72.1–78.7 | 78.5 | 75.2–81.4 | 2.9 | L | |

| 35–44 | 17.5 | 15.1–20.3 | 20.1 | 16.2–24.7 | 2.6 | 67.4 | 64.4–70.4 | 67.3 | 62.9–71.4 | −0.1 | ||

| 45–64 | 25.6 | 21.1–30.7 | 22.7 | 19.8–25.9 | −2.9 | 61.5 | 56.3–66.5 | 65.1 | 61.9–68.1 | 3.5 | ||

| 65+ | 41.6 | 36.5–46.9 | 32.8 | 28.7–37.1 | −8.8* | L | 44.0 | 38.8–49.3 | 52.6 | 47.9–57.2 | 8.6* | L |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 19.5 | 16.5–22.9 | 19.0 | 16.7–21.4 | −0.6 | 67.6 | 64.1–71 | 71.1 | 69.1–73.0 | 3.5 | Q | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 34.5 | 31.2–38.0 | 27.3 | 23.8–31.0 | −7.2* | L, Q | 51.3 | 46.8–55.8 | 61.6 | 57.8–65.2 | 10.3* | L |

| Hispanic | 32.3 | 27.6–37.4 | 24.7 | 22.3–27.4 | −7.6* | L | 56.3 | 51.0–61.5 | 65.2 | 61.5–68.6 | 8.9* | L |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 26.3 | 20.6–32.9 | 22.2 | 19.2–25.6 | −4.1 | 61.3 | 55.8–66.6 | 61.2 | 56.6–65.6 | 0.1 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| < High School Graduate | 30.9 | 27.9–34.1 | 31.0 | 27.8–34.4 | 0.1 | 58.0 | 54.5–61.4 | 57.5 | 53.8–61.1 | −0.5 | ||

| High School Graduate | 25.7 | 23.9–27.7 | 21.7 | 19.3–24.3 | −4.0* | L | 62.4 | 60.4–64.4 | 68.4 | 65.4–71.3 | 6.0* | L, Q |

| Some College | 20.5 | 17.8–23.6 | 19.8 | 17.1–22.9 | −0.7 | 66.4 | 62.7–69.9 | 67.5 | 64.5–70.3 | 1.1 | Q | |

| ≥College Graduate | 16.1 | 13.4–19.4 | 16.6 | 13.4–20.3 | 0.4 | 69.6 | 65.5–73.4 | 73.1 | 68.6–77.1 | 3.5 | ||

| BMI Category | ||||||||||||

| Normal/Underweight | 20.4 | 17.2–23.9 | 17.9 | 15.4–20.7 | −2.5 | 67.1 | 62.5–71.4 | 73.0 | 70.2–75.7 | 5.9* | L | |

| Overweight | 19.0 | 16.9–21.2 | 19.7 | 17.0–22.7 | 0.7 | 68.6 | 66.9–70.2 | 69.5 | 66.5–72.3 | 0.9 | ||

| Obesity | 28.0 | 25.3–30.8 | 22.4 | 19.9–25.1 | −5.6* | L, Q | 58.2 | 55.1–61.1 | 65.0 | 61.8–68.2 | 6.9* | L, Q |

Abbreviations: Chg=Change; PP=Percentage-Points; CI=Confidence Interval

Significantly different from 0 (Adjusted Wald Test P<0.05)

Letters indicate presence of significant trends: L=Linear; Q=Quadratic; C=Cubic

Leisure-time activity

When leisure-time physical activity was analyzed in isolation, neither inactivity nor insufficient activity exhibited significant trends over this period, while meeting the aerobic guideline in leisure time exhibited a statistically significant positive linear trend (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Age-adjusted prevalence of three levels of domain-specific physical activity participation among U.S. adults, NHANES 2007–2018

There was no overall change in the prevalence of leisure-time inactivity when comparing 2007/2008 to 2017/2018 among adults overall and for most subgroups. Exceptions included significantly lower inactivity in 2017/2018 versus 2007/2008 among adults aged ≥65 years and Hispanics (Table 3). These two groups and non-Hispanic Blacks also exhibited significant negative linear trends in leisure-time inactivity; trends were nonmonotonic among non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics. Adults with less than a high school education exhibited a significant higher-order trend in leisure-time inactivity with no accompanying significant linear trend. There was no overall change in the prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline in leisure time from 2007/2008 to 2017/2018 among adults overall and for most subgroups. Exceptions included significantly higher prevalence in 2017/2018 compared to 2007/2008 among adults aged ≥65 years, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics (Table 3). These groups, plus adults aged 25–34 years, also exhibited significant positive linear trends in meeting the guideline over this period. Estimates of leisure-time insufficient activity are available in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 3:

Prevalence of inactivity and meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline in leisure time activity among adults, NHANES 2007/2008 and 2017/2018

| Inactive | Meets Aerobic Guideline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | |||||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† |

| Overall | 48.2 | 43.4–53.1 | 45.8 | 42.4–49.3 | −2.4 | 35.3 | 31.4–39.5 | 38.6 | 35.9–41.3 | 3.3 | L | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 44.6 | 39.0–50.4 | 42.4 | 38.6–46.3 | −2.2 | 39.4 | 35.3–43.7 | 43.5 | 40.0–47.0 | 4.1 | ||

| Female | 51.5 | 47.1–55.9 | 48.8 | 44.9–52.8 | −2.7 | 31.5 | 27.4–35.9 | 34.1 | 31.1–37.3 | 2.6 | L | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 33.7 | 30.0–37.5 | 35.6 | 30.3–41.4 | 2.0 | 48.7 | 43.3–54.0 | 55.2 | 48.3–61.9 | 6.6 | ||

| 25–34 | 38.6 | 32.6–45.0 | 37.7 | 32.8–42.8 | −0.9 | 44.9 | 38.3–51.7 | 48.7 | 44.6–52.8 | 3.8 | L | |

| 35–44 | 43.7 | 38.4–49.1 | 46.7 | 40.2–53.4 | 3.1 | 37.8 | 34.3–41.4 | 35.5 | 30.6–40.7 | −2.3 | ||

| 45–64 | 54.5 | 46.5–62.3 | 48.8 | 43.4–54.2 | −5.7 | 29.9 | 23.6–37.1 | 33.2 | 28.0–39.0 | 3.3 | ||

| 65+ | 64.4 | 57.9–70.4 | 55.8 | 51.1–60.4 | −8.6* | L | 21.3 | 17.1–26.2 | 28.6 | 24.9–32.6 | 7.3* | L |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 43.8 | 36.3–51.5 | 42.8 | 38.2–47.5 | −0.9 | 38.4 | 32.3–44.9 | 40.1 | 36.8–43.6 | 1.7 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 57.1 | 54.5–59.6 | 52.0 | 47.5–56.6 | −5.0 | L, C | 28.6 | 25.5–31.9 | 35.5 | 32.4–38.8 | 7.0* | L |

| Hispanic | 63.1 | 60.0–66.1 | 53.7 | 50.2–57.2 | −9.4* | L, Q | 26.5 | 24.8–28.2 | 33.5 | 29.6–37.7 | 7.1* | L |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 48.5 | 40.8–56.2 | 45.7 | 40.0–51.5 | −2.8 | 31.9 | 25.8–38.7 | 38.5 | 32.9–44.4 | 6.6 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| < High School Graduate | 69.0 | 66.2–71.6 | 68.9 | 64.3–73.1 | −0.1 | Q | 20.3 | 17.6–23.3 | 21.2 | 18.4–24.3 | 0.9 | |

| High School Graduate | 55.2 | 50.2–60.1 | 57.6 | 54.1–61.1 | 2.5 | 30.9 | 27.2–34.9 | 27.9 | 26.0–30.0 | −3.0 | ||

| Some College | 43.8 | 38.5–49.4 | 45.2 | 41.8–48.7 | 1.4 | 36.1 | 31.8–40.7 | 39.1 | 35.5–42.8 | 3.0 | ||

| ≥College Graduate | 29.8 | 25.9–34.0 | 26.0 | 22.4–30.0 | −3.8 | 52.0 | 47.4–56.6 | 54.9 | 49.8–59.9 | 2.9 | ||

| BMI Category | ||||||||||||

| Normal/Underweight | 44.8 | 38.6–51.1 | 39.9 | 34.8–45.3 | −4.9 | 39.8 | 33.6–46.4 | 43.9 | 38.9–48.9 | 4.1 | ||

| Overweight | 42.8 | 37.6–48.1 | 40.3 | 37.2–43.4 | −2.5 | 39.0 | 34.0–44.3 | 44.6 | 40.2–49.2 | 5.6 | ||

| Obesity | 55.0 | 51.8–58.0 | 51.9 | 47.8–56.1 | −3.0 | 28.8 | 26.6–31.2 | 31.2 | 27.4–35.2 | 2.3 | ||

Abbreviations: Chg=Change; PP=Percentage-Points; CI=Confidence Interval

Significantly different from 0 (Adjusted Wald Test P<0.05)

Letters indicate presence of significant trends: L=Linear; Q=Quadratic; C=Cubic

Occupational/household activity

When occupational/household activity was analyzed in isolation, inactivity exhibited a significant nonmonotonic negative trend, insufficient activity exhibited a small but statistically significant positive linear trend, and meeting the aerobic guideline increased nonmonotonically (Figure 2). When focused on a particular time, changes in meeting the guideline were usually of similar magnitude to but in opposite direction from corresponding changes in inactivity.

The prevalence of occupational/household inactivity was significantly lower in 2017/2018 than in 2007/2008 overall and among most subgroups (Table 4). Additionally, most subgroups exhibited significant nonmonotonic negative linear trends, while only three (adults aged 35–44 years, non-Hispanic other, and adults who were overweight) exhibited higher-order trends with no accompanying significant linear trend. The prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline in occupational/household activity was significantly higher in 2017/2018 than in 2007/2008 overall and among women, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, adults with a high school education, and adults with obesity. Most subgroups exhibited significant nonmonotonic positive linear trends, while five groups (men, adults aged 35–44 years, non-Hispanic other, adults with at least a college degree, and adults with obesity) exhibited higher-order trends only. Estimates of occupational/household insufficient activity by subgroup are available in Supplemental table 2.

Table 4:

Prevalence of inactivity and meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline in occupational/household activity among adults, NHANES 2007/2008 and 2017/2018

| Inactive | Meets Aerobic Guideline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | |||||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† |

| Overall | 53.3 | 50.6–56.0 | 47.7 | 45.3–50.2 | −5.6* | L, Q | 39.7 | 37.2–42.4 | 44.2 | 41.3–47.2 | 4.5* | L, Q |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 45.5 | 41.3–49.7 | 41.7 | 38.6–44.7 | −3.8 | L, Q | 48.4 | 44.6–52.3 | 50.2 | 46.4–54.1 | 1.8 | Q |

| Female | 60.7 | 58.7–62.6 | 53.3 | 50.5–56.1 | −7.4* | L, Q | 31.6 | 29.7–33.6 | 38.6 | 35.7–41.7 | 7.0* | L, Q |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 46.2 | 40.9–51.6 | 40.1 | 34.9–45.5 | −6.1 | L, Q | 47.0 | 41.9–52.2 | 53.0 | 47.0–58.9 | 6.0 | L, Q |

| 25–34 | 46.5 | 42.0–51.0 | 39.7 | 35.5–44.1 | −6.8* | L, Q | 47.7 | 42.7–52.8 | 53.6 | 49.5–57.7 | 5.9 | L, Q |

| 35–44 | 53.4 | 48.3–58.5 | 50.2 | 46.1–54.3 | −3.3 | Q | 40.1 | 34.8–45.6 | 41.4 | 36.3–46.6 | 1.3 | Q |

| 45–64 | 52.7 | 49.3–56.0 | 48.1 | 45.7–50.6 | −4.6* | L, Q | 39.4 | 35.9–43.1 | 44.0 | 40.3–47.9 | 4.6 | L, Q |

| 65+ | 67.0 | 62.4–71.3 | 58.2 | 51.6–64.5 | −8.8* | L, Q | 25.8 | 22.2–29.8 | 31.5 | 26.0–37.7 | 5.7 | L, Q |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 49.0 | 46.3–51.7 | 43.9 | 40.8–47.0 | −5.1* | L, Q | 43.0 | 40.1–46.0 | 47.6 | 44.0–51.2 | 4.6 | L, Q |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 66.2 | 62.7–69.5 | 54.9 | 51.6–58.1 | −11.3* | L, Q | 29.3 | 25.9–32.9 | 38.8 | 35.0–42.6 | 9.5* | L, Q |

| Hispanic | 60.5 | 56.0–64.8 | 51.7 | 48.1–55.4 | −8.8* | L, Q | 35.2 | 31.1–39.6 | 42.2 | 38.2–46.4 | 7.0* | L, Q |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 64.8 | 57.1–71.8 | 59.7 | 54.0–65.2 | −5.1 | Q | 31.3 | 24.3–39.3 | 30.7 | 25.1–36.8 | −0.7 | Q |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| < High School Graduate | 54.4 | 50.9–57.9 | 52.5 | 49.3–55.7 | −1.9 | L, Q | 39.9 | 36.3–43.7 | 43.7 | 40.2–47.2 | 3.7 | L, Q |

| High School Graduate | 48.4 | 45.2–51.6 | 39.5 | 36.4–42.7 | −8.9* | L, Q | 45.0 | 42.5–47.5 | 54.4 | 50.8–57.9 | 9.4* | L, Q |

| Some College | 48.8 | 44.5–53.2 | 43.4 | 40.7–46.2 | −5.4* | L, Q | 44.7 | 40.4–49.0 | 47.1 | 44.7–49.6 | 2.4 | L, Q |

| ≥College Graduate | 60.3 | 55.7–64.6 | 56.7 | 52.1–61.1 | −3.6 | L, Q | 31.1 | 26.5–36.0 | 33.0 | 29.3–37.0 | 1.9 | Q |

| BMI Category | ||||||||||||

| Normal/Underweight | 53.0 | 49.3–56.7 | 48.0 | 42.9–53.2 | −5.0 | L, Q | 38.7 | 35.6–42.0 | 44.4 | 39.2–49.7 | 5.7 | L, Q |

| Overweight | 50.5 | 47.2–53.7 | 50.5 | 47.7–53.4 | 0.1 | Q, C | 42.9 | 40.2–45.6 | 42.1 | 38.7–45.5 | −0.8 | Q, C |

| Obesity | 55.6 | 51.6–59.4 | 43.7 | 40.0–47.5 | −11.8* | L, Q | 37.9 | 34.4–41.6 | 47.1 | 43.8–50.5 | 9.2* | L, Q |

Abbreviations: Chg=Change; PP=Percentage-Points; CI=Confidence Interval

Significantly different from 0 (Adjusted Wald Test P<0.05)

Letters indicate presence of significant trends: L=Linear; Q=Quadratic; C=Cubic

Transportation activity

When transportation activity was analyzed in isolation, inactivity increased nonmonotonically, insufficient activity exhibited no significant trend, and meeting the aerobic guideline exhibited a negative nonmonotonic trend (Figure 2).

There was no overall change in the prevalence of transportation-related inactivity from 2007/2008 to 2017/2018, but the prevalence was significantly higher in 2017/2018 compared to 2007/2008 among women (Table 5). There were significant nonmonotonic positive linear trends in inactivity among women, adults aged 45–64 years, non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, adults with less than a high school education or some college, and adults with obesity. Adults aged 18–24 years exhibited a significant positive linear trend while men, adults aged 35–44 years, non-Hispanic Blacks, college graduates, and adults who were overweight exhibited only higher-order trends with no accompanying significant linear trend. The prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline in transportation activity was not significantly different in 2017/2018 than in 2007/2008 overall or among any subgroups (Table 5). Ten of 18 subgroups examined in this analysis exhibited significant positive linear trends (8 of which were nonmonotonic). Hispanics and adults with a college education exhibited higher order trends with no accompanying linear trend. Estimates of transportation-related insufficient activity by subgroup are available in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 5:

Prevalence of inactivity and meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline in transportation activity among adults, NHANES 2007/2008 and 2017/2018

| Inactive | Meets Aerobic Guideline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | 2007/2008 | 2017/2018 | Chg | |||||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | PP | Trend† |

| Overall | 76.1 | 72.7–79.2 | 78.1 | 76.0–80.0 | 2.0 | L, Q, C | 13.6 | 11.3–16.3 | 10.9 | 9.6–12.4 | −2.7 | L, Q, C |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 74.4 | 70.1–78.4 | 74.9 | 72.1–77.6 | 0.5 | Q, C | 15.6 | 13.1–18.4 | 12.6 | 10.3–15.3 | −3.0 | L, Q |

| Female | 77.7 | 74.6–80.4 | 81.1 | 79.3–82.8 | 3.4* | L, Q | 11.8 | 9.4–14.7 | 9.4 | 8.1–10.8 | −2.5 | L, Q, C |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 62.5 | 55.7–68.8 | 68.5 | 60.9–75.3 | 6.0 | L | 21.9 | 16.8–27.9 | 16.3 | 10.2–25.0 | −5.6 | |

| 25–34 | 72.7 | 67.9–77.1 | 73.5 | 68.4–78.0 | 0.8 | 17.2 | 13.4–21.8 | 13.4 | 10.6–16.9 | −3.7 | ||

| 35–44 | 76.3 | 71.3–80.7 | 76.3 | 71.4–80.5 | −0.1 | C | 12.8 | 10.6–15.5 | 10.7 | 8.3–13.7 | −2.2 | L, C |

| 45–64 | 79.4 | 74.9–83.3 | 82.7 | 80.4–84.8 | 3.2 | L, Q | 11.4 | 9–14.4 | 9.3 | 7.8–11.1 | −2.1 | L, Q, C |

| 65+ | 84.0 | 80.6–86.9 | 84.6 | 81.2–87.6 | 0.7 | 8.5 | 6.8–10.5 | 7.4 | 5.3–10.4 | −1.1 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 77.6 | 75.0–80.0 | 80.9 | 78.3–83.3 | 3.3 | L, Q | 12.5 | 10.2–15.1 | 9.4 | 7.6–11.5 | −3.1 | L, Q |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 77.7 | 73.3–81.5 | 74.6 | 71.1–77.9 | −3.1 | Q, C | 11.4 | 8.9–14.4 | 13.2 | 10.8–15.9 | 1.8 | Q, C |

| Hispanic | 70.6 | 64.8–75.8 | 73.6 | 69.8–77.1 | 3.0 | L, C | 18.9 | 14.8–23.8 | 14.4 | 11.5–17.8 | −4.5 | L |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 69.6 | 54.7–81.3 | 70.4 | 64.6–75.7 | 0.9 | 17.6 | 10–29.1 | 13.3 | 11.0–15.9 | −4.3 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| < High School Graduate | 70.4 | 65.1–75.2 | 73.2 | 68.2–77.6 | 2.7 | L, C | 19.8 | 15.5–25 | 14.3 | 11.2–18.0 | −5.6 | L |

| High School Graduate | 78.7 | 74.3–82.4 | 78.0 | 75.3–80.5 | −0.6 | 11.3 | 8.8–14.3 | 12.0 | 10.2–14.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Some College | 76.1 | 72.3–79.5 | 80.5 | 77.3–83.3 | 4.4 | L, Q, C | 13.6 | 11–16.6 | 9.5 | 7.6–11.7 | −4.1 | L, Q, C |

| ≥College Graduate | 77.6 | 72.4–82.0 | 78.6 | 74.7–82.1 | 1.1 | Q | 11.6 | 9.2–14.5 | 9.8 | 7.7–12.5 | −1.8 | Q |

| BMI Category | ||||||||||||

| Normal/Underweight | 72.2 | 67.3–76.7 | 73.4 | 69.9–76.7 | 1.2 | 16.7 | 13.3–20.8 | 13.8 | 11.5–16.6 | −2.9 | ||

| Overweight | 76.8 | 74.0–79.3 | 77.4 | 73.1–81.2 | 0.6 | Q | 12.4 | 10.2–15.1 | 10.9 | 8.5–13.9 | −1.5 | L, Q |

| Obesity | 79.1 | 76.0–82.0 | 82.4 | 79.8–84.7 | 3.3 | L, Q, C | 11.8 | 9.3–14.7 | 9.1 | 7.6–10.7 | −2.7 | L, C |

Abbreviations: Chg=Change; PP=Percentage-Points; CI=Confidence Interval

Significantly different from 0 (Adjusted Wald Test P<0.05)

Letters indicate presence of significant trends: L=Linear; Q=Quadratic; C=Cubic

Discussion

Among U.S. adults from 2007/2008 to 2017/2018, the prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline through multi-domain activity increased while the inactivity decreased linearly overall and for several subgroups, including several subgroups with previously-documented low activity participation (e.g. adults aged ≥65 years, non-Hispanic Blacks). Changes in domain-specific physical activity participation varied, but the combined occupational/household domain exhibited the most consistent increases in meeting the guideline and decreases in inactivity across subgroups. Efforts to continue increases in participation among subgroups that have historically reported lower physical activity levels than their peers may help narrow disparities in physical activity participation. Further, many adults reported no transportation activity; interventions designed to increase transportation activity, including providing activity-friendly routes to everyday destinations may address this low participation.

When all domains were considered, the magnitude of increase in meeting the aerobic guideline varied across subgroups, helping to reduce previously documented disparities in physical activity participation.4,10,14 For example, in 2007/2008, there was a 31.6 percentage point difference in meeting the aerobic guideline when comparing adults aged 65 years or older (44.0%) to those aged 25–34 years (75.6%), and this difference narrowed to 25.9 percentage points in 2017/2018 (52.6% and 78.5%, respectively). Similar findings were observed when comparing non-Hispanic Blacks or Hispanics to non-Hispanic Whites, and when comparing adults with a high school education to adults with a college education. Physical activity confers many health benefits2 and is associated with reduced healthcare costs15; continued narrowing of differences in participation in the groups above could help address health disparities and the economic burden thereof. Physical activity promotion efforts that are tailored to these groups could continue this progress in equitable physical activity participation.16,17

This manuscript extends previously reported findings on multi-domain physical activity from NHANES. In 2019, Du, et al., examined changes in multi-domain physical activity among adults aged 20 years and older in NHANES 2007/2008 to 2015/2016.8 They reported no significant trends in prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline overall, but significant linear increases were observed among selected subgroups, including women and non-Hispanic Blacks. In our study, after adding data from 2017/2018, there was a significant trend for meeting the aerobic guideline overall and for several additional subgroups. Further, our analysis suggests the increase in meeting the guideline is accompanied by decreases in inactivity. This apparent trend for greater prevalence of meeting the guideline and lower prevalence of inactivity is encouraging as it aligns with the Guidelines recommendation to avoid inactivity. Also, shifting physical activity participation from lower to higher categories is the goal of CDC’s Active People, Healthy NationSM initiative to increase the activity levels of 27 million Americans by 202718. If sustained, the changes documented here may help reach this goal.

These and other recent results6,8 suggest over two thirds of adults meet the aerobic guideline when all domains of activity are assessed. As would be expected, this is higher than leisure-only assessments from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), in which 50.2% of adults met the guideline in 2018.19 These results are encouraging, as it appears many adults are benefiting from the health benefits of meeting the aerobic guideline, but should be interpreted with some caution. Previous reports suggest multi-domain physical activity questionnaires may lead to overreporting among respondents.20 Continued advancement of physical activity assessment techniques, including mobile applications21, device-based measurement of bodily movements21, and crowd-sourced or “big-data” approaches22 may allow refinement of these estimates in future surveillance efforts.

Domain-specific findings can identify the contexts in which physical activity is changing and provide insights for future activity promotion strategies. For example, we documented increases in meeting the guideline in multi-domain activity among non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics. Domain specific analyses suggest these changes can be attributed to increases in meeting the guideline during leisure and occupational/household activities, while transportation activity changed inconsistently (non-Hispanic Blacks) or decreased (Hispanics). The generally low prevalence of meeting the guideline during transportation activity among these and other subgroups suggests active transportation may be an underutilized source of aerobic activity.23 Providing activity friendly routes to every day destinations is a proven strategy to increase physical activity in general and may particularly favor walking and bicycling to get from place to place (i.e., for transportation).9 Tailoring such interventions to the needs of individuals most likely to report low activity participation could help to continue the narrowing of physical activity disparities documented in this report.

In estimates limited to leisure-time physical activity, we found a linear increase in the prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline among adults overall. This finding agrees with recent reports from NHIS showing overall increases in meeting the aerobic guideline in leisure time3,19, but the prevalence was consistently lower in NHANES than NHIS (e.g. 38.6% in 2017/2018 in NHANES and 54.2% in 2018 in NHIS19). The reasons for these discrepant prevalence estimates are not entirely clear, but differences in assessment may play a role. In NHANES, leisure activity is assessed after occupational/household and transportation activities are reported, and respondents are asked to exclude activities reported in preceding sections; some activities that are not clearly leisure (e.g. gardening or walking the dog) could be reported under other domains. Conversely, all such activities might be captured under leisure activity in NHIS, which is the only domain assessed. Moreover, NHIS asks respondents to report participation in light-intensity activity combined with moderate-intensity activity. Thus, although both NHANES and NHIS assess ‘leisure-time physical activity’, the estimates derived from each represent slightly different constructs, and comparisons should be made with caution. Advances in physical activity assessments that better differentiate among domains and activity intensity (e.g., the ACT24 smartphone-based activity diary21,24) may better disentangle the relationships among leisure, household, occupational, and transportation activities.

In the combined occupational/household domain, the patterns of change were markedly similar across subgroups and the overall sample: meeting the guideline in this domain decreased to a low-point in 2011/2012 then increased thereafter, resulting in significant, though inconsistent, trends for increasing prevalence of meeting the guideline in this domain. Trends in inactivity formed a near mirror image of those for meeting the guideline. Deciphering the underlying cause of these results is difficult given the combination of occupational and household activities in a single assessment; changes in either or both could account for the observed results. Previous reports have documented a decades-long reduction in the physical demands of the U.S. workforce beginning in the 1960s.25 Assuming this long-term trend has continued, these findings could suggest increased household activity since 2011/2012. Again, additional surveillance with assessment techniques that better disentangle activity domains could clarify these changes.

This report is subject to at least three limitations. First, NHANES physical activity data are self-reported and subject to social desirability and other recall biases20; it is unknown if these biases differ across domains. Second, we performed a complete case analysis, which could bias results if those with complete information are different from those without; however, physical activity data were complete for over 99% of the analytic sample. Finally, multi-domain activity questionnaires may encourage over-reporting due to activity being counted in multiple domains20, which would lead to overestimation of activity prevalence. Strengths of this article include a large, nationally representative sample.

Conclusion

Among U.S. adults from 2007/2008 to 2017/2018, the prevalence of meeting the aerobic physical activity guideline using multi-domain activity increased and inactivity decreased overall and for several subgroups. Domain-specific analyses suggest activity increased and inactivity decreased most consistently in the occupational/household domain. Several subgroups with previously documented low activity participation (e.g. adults aged ≥65 years, non-Hispanic Blacks) reported increased prevalence of meeting the aerobic guideline relative to their more-active counterparts. Transportation-related activity may be an underutilized source of physical activity in this country.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC nor the NIH

References (*PLACEHOLDER denotes references to other supplement articles, to be updated before publication)

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in meeting the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines, 2008–2017. 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/downloads/trends-in-the-prevalence-of-physical-activity-508.pdf. Accessed 6 February 2019.

- 4.United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2020 Topics and Objectives, Physical Activity. 2020; https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/physical-activity/objectives. Accessed 6 February 2020.

- 5.Whitfield GP, Carlson SA, Ussery EN, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, Petersen R. Trends in Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines Among Urban and Rural Dwelling Adults - United States, 2008–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(23):513–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitfield GP, Ussery EN, Carlson SA. Combining Data From Assessments of Leisure, Occupational, Household, and Transportation Physical Activity Among US Adults, NHANES 2011–2016. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. Accessed 14 August 2020.

- 8.Du Y, Liu B, Sun Y, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Trends in Adherence to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans for Aerobic Activity and Time Spent on Sedentary Behavior Among US Adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(7):e197597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity. 2018; https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/physical-activity. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 10.Scholes S, Bann D. Education-related disparities in reported physical activity during leisure-time, active transportation, and work among US adults: repeated cross-sectional analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2007 to 2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2012 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies Physical Activity (PAQ_G). 2013; https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2011-2012/PAQ_G.htm. Accessed 6 February 2020.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html. Accessed 26 January 2021.

- 13.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes. 2001(20):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2018. In. Hyatsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Pratt M, Yang Z, Adams EK. Inadequate physical activity and health care expenditures in the United States. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57(4):315–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Digital Health Interventions for Adults 55 years and Older. 2019; https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/PA-Digital-Health-55-Years-Older.pdf. Accessed 27 January 2021.

- 17.Zubala A, MacGillivray S, Frost H, et al. Promotion of physical activity interventions for community dwelling older adults: A systematic review of reviews. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulton JE, Buchner DM, Carlson SA, et al. CDC’s Active People, Healthy Nation(SM): Creating an Active America, Together. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(7):469–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitfield GP, Hyde ET, Carlson SA. *PLACEHOLDER* Participation in Leisure-Time Aerobic Physical Activity among Adults, National Health Interview Survey, 1998 – 2018 J Phys Act Health. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rzewnicki R, Vanden Auweele Y, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Addressing overreporting on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) telephone survey with a population sample. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(3):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews CE, Kozey Keadle S, Moore SC, et al. Measurement of Active and Sedentary Behavior in Context of Large Epidemiologic Studies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(2):266–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee K, Sener IN. Emerging data for pedestrian and bicycle monitoring: Sources and applications. Transport Res Interdisc Persp. 2020;4:100095. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitfield GP, Paul P, Wendel AM. Active Transportation Surveillance - United States, 1999–2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;64(7):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saint Maurice P et al. *PLACEHOLDER* Amount, Type, and Timing of Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity Among US Adults. J Phys Act Health. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Trends over 5 Decades in U.S. Occupation-Related Physical Activity and Their Associations with Obesity. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.