Abstract

Introduction:

Orthodontic tooth movement (OTM) relies on efficient remodeling of alveolar bone. While a well-controlled inflammatory response is essential during OTM, the mechanism regulating inflammation is unknown. Autophagy, a conserved catabolic pathway, has been shown to protect cells from excess inflammation in disease states. We hypothesize that autophagy plays a role in regulating inflammation during OTM.

Methods:

A split mouth design was used to force load molars in adult male mice, carrying a GFP-LC3 transgene for in vivo detection of autophagy. Confocal microscopy, Western blot and qPCR analyses were used to evaluate autophagy activation in tissues of loaded and control molars at time points after force application. Rapamycin, a Food and Drug Administration-approved immunosuppressant, was injected to evaluate induction of autophagy.

Results:

Autophagy activity increases shortly after loading, primarily on the compression side of the tooth, and is closely associated with inflammatory cytokine expression as well as osteoclast recruitment. Daily administration of rapamycin, an autophagy activator, led to reduced tooth movement and osteoclasts, suggesting autophagy downregulates the inflammatory response and bone turnover during OTM.

Conclusions:

This is the first demonstration that autophagy is induced by orthodontic loading and plays a role during OTM, likely via negative regulation of inflammatory response and bone turnover. Exploring roles of autophagy in OTM holds great promise, as aberrant autophagy is associated with periodontal disease and its related systemic inflammatory disorders.

Introduction

Orthodontic tooth movement (OTM) combines bone remodeling with reversible periodontal injury due to mechanical strain. Under healthy conditions, movement is achieved by coordinated bone adaptation, involving osteoclast resorption of compressed bone and osteoblast bone formation under tension. This process is regulated by an aseptic inflammatory response characterized by release of inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins and cytokines. Inflammation leads to vasodilation and permeability, prompting leukocyte migration into paradental extracellular matrix. Migratory leukocytes, fibroblasts and osteoblasts, activate an inflammatory cascade through chemokines and cytokines.1,2,3,4,5 Cytokines act on periodontal ligament (PDL) cells, promoting osteoclastogenesis through upregulation of Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand (RANKL).6,7,8 Increased RANKL combined with decreased osteoprotegerin (OPG) release by osteoblasts favors osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Release of cytokines Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Tissue Necrosis Factor-α (TNFα) induce osteoclast differentiation, function, and survival.9,10,11 At the tension side, Interleukin-10 (IL-10) level is increased, boosting OPG and reducing RANKL production by osteoblasts, which favors bone deposition through inhibition of osteoclast formation.10 Transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) level is also elevated under tension, which recruits PDL cells and differentiating osteoblast precursors.12,13

Extensive studies have dissected OTM signaling cascades, but little is known about how inflammation is regulated during OTM. In healthy patients, load-induced inflammation is well-controlled, with PDL space remaining fairly constant.14 Inflammation resolves and tissues return to homeostasis, but it is unknown how inflammation is downregulated after OTM. To identify potential regulatory mechanisms, we are investigating the role of autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved self-protective modulator of inflammation.15,16 Defective autophagy contributes to diseases with chronic or dysregulated inflammation such as periodontitis, systemic lupus erythematosis, and inflammatory bowel disease.15,16,17,18 Functional autophagy modulates inflammation-inducing processes for proper resolution of systemic disease16; we aim to explore if autophagy regulates OTM through a similar mechanism.

The most studied form of autophagy is macroautophagy, henceforth referred to as autophagy. Autophagy is an intracellular catabolic pathway induced by stressful conditions including starvation, hypoxia, toxin accumulation, or damaged organelles.16,17,18,19 During normal conditions, UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) is negatively regulated by mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), but under stress, AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits mTOR and phosphorylates ULK1, initiating autophagy (Fig 1).16,20 Activation results in autophagosome formation, a double-membraned organelle that sequesters damaged cytosolic components. Phagophore formation begins with the Beclin-1/VPS34 class III PI3K complex, followed by ATG protein conjugation, LC3 membrane insertion, and capture of targets for degradation (Fig 1).20 The mature autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome; sequestered contents with cargo receptor p62 are broken down and released back to the cytosol for reuse.19,21

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the autophagy pathway.

The schema summarizes the main steps of autophagy activation and flux, with labels for key proteins. Autophagy is an intracellular survival mechanism and modulator of inflammation. Under stressful conditions, AMPK inhibits mTOR and phosphorylates ULK1, initiating autophagy.16,20 Then activated ULK1-protein complex targets Beclin-1/VPS34 class III PI3K complex, which recruits downstream ATG proteins and promotes formation of the autophagosome, a double-membraned organelle that sequesters cytosolic components. During autophagosome maturation, cytoplasmic LC3I is translocated to autophagosomes, where LC3I is conjugated with phosphatidylethanolaminie (PE) to form lipidated LC3II.20 Lipidated LC3II represents a dynamic marker for autophagy.20 Finally, mature autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, where the engulfed components marked with autophagy receptor p62, are degraded and recycled.19,21

In addition to canonical roles in homeostasis and cell survival, autophagy is important in host defense through crosstalk with inflammation. Autophagy can modulate inflammation through regulation of proinflammatory cytokines and inhibition of inflammasome activation and production of IL-1β and IL-18.16,22,23 Th1 type/proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα induce autophagy,24 whereas Th2-type cytokines IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 suppress autophagy induction by activating mTOR.24,25

Furthermore, a growing literature ties autophagy to bone turnover. Microgravity induces autophagic activity in pre-osteoclasts prompting differentiation.26

Murine studies in rheumatoid arthritis show TNFα induces autophagy in osteoclasts, while activation of autophagy through Beclin-1 overexpression promotes osteoclastogenesis and resorption.27 Nollet et al.28 found autophagy induced in osteoblasts during mineralization under oxidative stress. Osteoblasts with defective autophagy show increased oxidative stress and secretion of RANKL, favoring generation of osteoclasts and bone resorption; osteoblast-specific autophagy-deficient mice lost half their trabecular bone mass.28

With mounting evidence of crosstalk between autophagy, inflammation, and bone metabolism, we aimed to investigate roles of autophagy in regulating the orthodontically induced inflammatory response and bone turnover using an established mouse model of OTM.26 Basal levels of autophagy are observed in dental pulp and odontoblasts during homeostasis and autophagy markers, LC3 and Beclin-1, are expressed throughout odontogenesis.29,30,31,32 Autophagy is active in the developing and adult dentition, yet our knowledge of its roles is highly limited. Using a transgenic mouse model with a fluorescently tagged autophagy protein LC3, we are the first group to demonstrate autophagy activation in response to mechanical loading in vivo. This is a critical first step to exploring roles of autophagy in OTM, which holds great promise, as aberrant autophagy is associated with periodontal disease and its related systemic inflammatory disorders, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.17,33 We hypothesize that autophagy is induced in peri-dental tissues in response to orthodontic loading of teeth and regulates load-induced inflammation and bone turnover.

Material and methods

Orthodontic force application is an established murine model in OTM studies. Optimal conditions have been characterized.26 Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (100 mg/kg) solution. We employed a split-mouth design, where thirty grams (=0.3 N) of force was delivered to the maxillary right first molar in the mesial direction, by bonding a nickel-titanium (NiTi) closed coil spring (American Orthodontics, Cat# 855–181, length adapted to each mouse’s mouth) between the maxillary right first molar and incisors with light-cured resin (Transbond Supreme LV, 3M Unitek, Morovia, Calif) (Fig 2, A–C). No spring reactivation was performed after bonding. All animal care procedures followed the ethical regulations for animal experiments, defined by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. All mice were monitored daily and given softened food after spring loading; no significant weight loss occurred during the experiment period.

Figure 2. Orthodontic loading activates autophagy.

A-J’’, Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope imaged sections of first molar distal roots from GFP-LC3 mice post-loading. A-J: Magnification x40, scale bar: 150 μm; A’- J”: Magnification x60, scale bar: 100 μm; A’-J’: Mesial PDL zoom-in (left yellow box in A). A’’-J’’: Distal PDL zoom-in (right yellow box in A). F-J’’: Experimental: Mesial, compression-left. Distal, tension-right. F, Large yellow arrow indicates direction of force application with compression/mesial on the right and tension/distal on the left. F’, F’’: Arrowheads: zoomed-in cells with puncta. Green: GFP-LC3; Blue: DAPI nuclei. K, Quantification of autophagosome puncta versus days post-loading in PDL of control and loaded molars on the mesial side of the molars. Fluorescent puncta quantified in a uniform (100 μm x 150 μm) area using Image J. L, Quantification of autophagosome puncta versus days post-loading in PDL of control and loaded molars on the distal side of the molars. M, Western blot analysis of phospho-Ulk1 and p62.

For histomorphometric analyses, that is OTM distance measurement, detection of autophagy activity and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining, we utilized a GFP-LC3 reporter mouse line.34,35 GFP-tagged LC3 is expressed under the LC3 promoter and inserted into the autophagosome membrane with autophagy induction (Fig 1)36,37; this yields green fluorescent puncta throughout the cytoplasm, visible with confocal microscopy (Fig 2). An increase of intracellular LC3-autophagosome puncta indicates autophagy induction or downstream suppression, which was imaged and quantified to measure autophagy activity in vivo.38

Orthodontic force application in mice using a split-mouth design is a well-accepted model (Fig 2, A–C).39 Thirty GFP-LC3 adult male mice (8–9 weeks old, in C57BL/6 background) were subdivided into 6 groups (n=5 for each group) for sacrifice at 6 different time points (days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10) after spring loading.

For molecular analyses, that is mRNA/quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western Blot, 60 wild-type adult male mice (C57BL/6, 8–9 weeks old, obtained from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were subdivided into 6 groups, to be killed at 6 different time points (days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10). Half of each group (n=5) was used for mRNA/qRT-PCR and half (n=5) for Western Blot experiments.

For rapamycin injection experiments, intraperitoneal injection of rapamycin (6 mg/Kg/day) or rapamycin vehicle (control) solution were given to mice daily beginning on the day of spring placement and until the mice were killed. The half-life of rapamycin in mouse blood was found to be 15 hours.40 Rapamycin was initially injected at a dosage of 8mg/kg/day as previously described36; however, at this dose, our experimental mice experienced toxicity demonstrated by lethargy and weight loss, compared to the control vehicle group. As a result, we titrated lower rapamycin dosages and found 6mg/kg/day was well-tolerated by mice. Rapamycin solution was made as previously described.37 Briefly, a 20mg/ml stock solution of rapamycin (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) was prepared in ethanol. The stock solution was diluted to 1.2 mg/ml in vehicle solution (saline containing 5% polyethylene glycol 400 and 5% Tween-80). The vehicle solution was prepared under the same conditions without inclusion of rapamycin. Sixty GFP-LC3 adult male mice (8–9 weeks old, in C57BL/6 background) were subdivided into 6 groups (n=10 for each group, half injected with rapamycin and half injected with rapamycin vehicle solution), and were killed at different time points (days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10) after spring loading. For molecular analysis, 10 wild-type adult male mice (C57BL/6, 8–9 weeks old, from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), half injected with rapamycin and half injected with rapamycin vehicle solution, were killed 1 day post-spring loading for mRNA/qRT-PCR experiment.

The occlusal view of the maxilla was imaged using a stereomicroscope (SMZ18, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) with an adapted digital camera (Nikon Instruments). NIS-Elements Basic Research imaging software was used for distance measurements, by measuring the distance between two parallel lines tangent to the convex regions distal to the first molar and mesial to the second molars (n=5 for each time point). Both the experiment (E) and control (C) sides were measured. The OTM distance measurement of the upper right first molar was determined by subtracting the measurement of the C unloaded side measurement from the E loaded side (OTM distance = E side value − C side value).

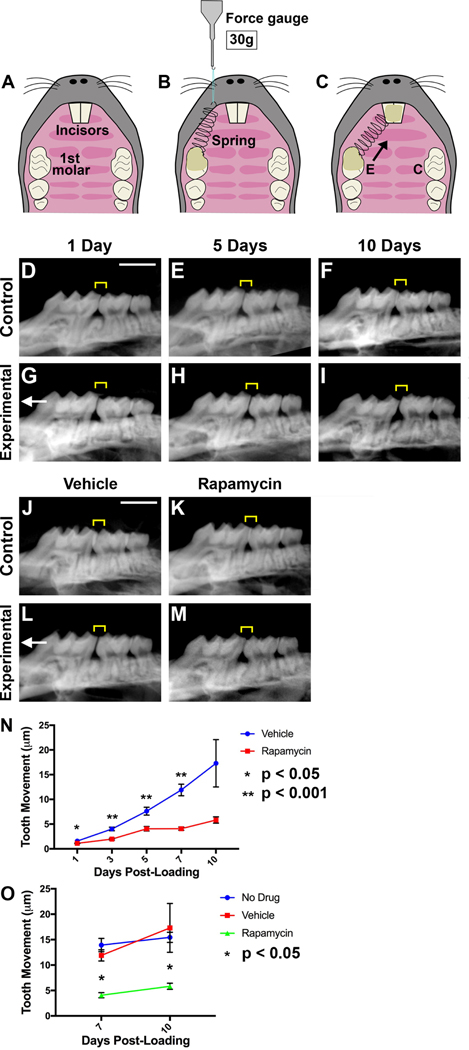

To confirm measurements taken on the stereomicroscope, microcomputed tomography (microCT) radiographs were taken at days 1, 5, and 10 post-loading. Mice maxillae were harvested at each time point (days 1, 5, and 10) and immediately fixed in 10% neutral formalin solution for 3 days. MicroCT radiographs of the maxillae were acquired using Skyscan 1275 (Skyscan, Aartselaar, Belgium) with the X-ray source set at 50 kV and 200 μA. Each sample was rotated 360° and imaged every 0.1° at 8 μm image pixel size, with an exposure time of 35 ms and averaging of 3 frames per view. two-dimensional images from the bucco-lingual midpoint of the first and second molar were extracted from the three-dimensional volumetric file. MicroCT two-dimensional images and measurements were taken at the height of contour between the first and second molars.

Adult male mice were killed with CO2 asphyxiation. Tissue preparation procedures were conducted as previously described with modification.18 Maxillae including part of the scalp were dissected free of adherent tissue and placed in a processing/embedding cassette (Fisher Scientific, Cat #15–182–706). Samples were fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde (4 °C, 3 days), followed by decalcification in 14% EDTA solution (4 °C, 4 days). After ×1 phosphate buffered saline (PBS) washes (1–2 hours, room temperature), samples were equilibrated in 30% sucrose ×1 PBS solution overnight at 4°C. Each maxilla was bisected and embedded in OCT compound (Fisher Healthcare, Cat # 23–730–571) containing base mold (Fisherbrand, Cat # 22–363–553). Embedding media was flash frozen on a metal platform prechilled in a dry ice-ethanol bath. Molds were wrapped in aluminum foil and stored at −80 °C. Cryosectioning (6 μm thickness) was performed on a Leica CM 1520 (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and sections were collected consecutively on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisherbrand, Cat # 22–037–246). Slides were stored at −20 °C.

For GFP imaging, frozen sections were washed with ×1 PBS and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma Aldrich, Cat # D9542–10MG). Slides were mounted using VectaShield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Cat # H–1000) with coverslips. Sections were imaged on Zeiss LSM 710 Laser Scanning Confocal microscopes. Images were analyzed using Imaris (Bitplane) and Photoshop (Adobe). A trained technician reviewed each image at a uniform magnification and counted intracellular puncta and nuclei in a fixed rectangular area overlaid on the image. Puncta were defined as small, discrete points of green fluorescence visible within the cytoplasm, distinct from other intracellular structures.

TRAP staining was performed as described.41 Sections were counterstained with Mayers/Harris Hematoxylin for 1–2 minutes, dehydrated, and mounted with coverslip using VectaShield Hard Set mounting medium. Images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U inverted microscope, using NIS-Elements Basic Research imaging software (Nikon Instruments Inc.). Brightfield (BF) was used for cellular visualization at x20 magnification with an average exposure time of 100ms.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR were performed for each animal individually (n=5 at all time points). After sacrifice, maxillary first molars and their peri-dental tissues (PDL and alveolar bone) were extracted; because of the miniscule size of mouse molars and the resulting inability to separate peri-dental tissues from the root and from each other, tissue was processed in total. Tissue total RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The resultant DNA-free RNA was diluted in RNase-free water and quantified by the Nanodrop (Thermo) at 260 nm. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Cat # 170–8891). The iTaq™ Universal SYBR Green Supermix Kit (Bio-Rad, Cat # 172–5120) was used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis. Primers were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems) and synthesized by Invitrogen (Table 1). Genes assayed included inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, Il-6, Il-1β, and Nuclear Factor of Activated T Cells-1 (NFATC1)), bone turnover markers (RANKL, OPG and Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9)) and autophagy pathway genes (Becn1, LC3 and Atg5). Relative differences in gene expression between groups were determined from cycle time (Ct) values. The values were normalized to beta-2-microglobulin (B2M, an internal positive control) in the same sample (ΔCt) and expressed as fold-change over day 0 control (2−ΔΔCt).24 Real-time fluorescence detection was carried out using an ABI StepOnePlus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-qPCR

| Gene | Forward (5’ to 3’) | Reverse (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|---|

| Becn1 | ATGGAGGGGTCTAAGGCGTC | TCCTCTCCTGAGTTAGCCTCT |

| Atg5 | TGTGCTTCGAGATGTGTGGTT | GTCAAATAGCTGACTCTTGGCAA |

| Lc3 | GACCGCTGTAAGGAGGTGC | CTTGACCAACTCGCTCATGTTA |

| Il-1β | TTCAGGCAGGCAGTATCACTC | GAAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC |

| Il-6 | TAGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC | TTGGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTC |

| Nfatc1 | GACCCGGAGTTCGACTTCG | TGACACTAGGGGACACATAACTG |

| Tnfα | CCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT | GCTACGACGTGGGCTACAG |

| B2m | TTCTGGTGCTTGTCTCACTGA | CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC |

At sacrifice, maxillary first molars (n=5) and their peri-dental tissues were extracted and pooled from the experimental (E, loading) or control (C, non-loading) sides; tissues were processed together as it is not currently possible to separate tiny murine teeth from their PDL, despite attempts. Non-loaded, maxillary first molars were collected as a day 0 control. Specimens were incubated on ice for 20 minutes with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer plus protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, protease inhibitor cocktail, Cat #11836153001), PMSF (1 mM) and E64 (2 mg/ml). Pre-chilled pestles (Fisherbrand, Cat 12–141–364) were used to grind tissues. After centrifugation to remove cell debris, supernatants were transferred to a pre-cooled tube and heated with ×1 sodium dodecyl sulphate buffer (95°C, 5 minutes). Samples were either directly loaded to odium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels or saved at −80 °C until Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed as described.25 For each time point, 45 μL protein lysates per lane were loaded to 4–20% Criterion TGX Stain-Free Proteingels (BioRad, Cat #5678093). Target proteins were immunodetected using appropriate primary and peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch). Primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) include: phopho-ULK1 (Ser 555) (Cell Signaling Cat #5869), p62 (Cell Signaling Cat #5114), LC3b (Cell Signaling Cat #2775), and Actin (Santa Cruz, Cat # sc-1616). Finally, proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Bioscience).

Statistical analysis

The data in each group was expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data were normally distributed; therefore, comparison among different groups from different time points were analyzed by two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by effect and contrast test (p=0.05). For puncta data (Fig 2), ANOVA was used to test whether the mean of the experimental outcome is different than the control outcome. The analysis was adjusted for repeated measurements from the same mouse using random effects to account for dependence between outcomes in the same mouse. For quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) data (Fig 3), ANOVA was used to test whether the mean of experimental outcome is different than 1 (control reference value).

Figure 3. Expression qPCR analysis of autophagy, inflammatory and bone turnover markers.

Expression of autophagy (A-C, BECN1, LC3, ATG5), bone turnover (D-F, RANKL, OPG, MMP9), and inflammatory markers (G-H, NFATC1, TFNα, IL-1β) increases in peri-dental tissues after orthodontic loading at time points days 1, 3, 5, and 10 after loading. Inflammatory marker Il-6 was not transcriptionally altered in peri-dental tissues after loading.

Results

Adult GFP-LC3 mice had a NiTi spring bonded to their central incisors and first molars, applying 30 g of force to orthodontically move teeth (Fig 4, A–C). Molar displacement linearly increased from days 1 to 10 (Fig 4,N; R2=0.98 linear correlation between time and amount of OTM). Upon loading, we found that LC3-GFP signal was activated as early as day 1 in the compression (mesial) side, located more apically (Fig 2, F–J). Compression side GFP+ puncta increased from day 3 to day 7, peaking at day 7 with activity extending more coronally (Fig 2, F–K, F’’–J’’). By contrast, there was minimal change in autophagic puncta on the tension (distal) side (Fig 2, F–J, F’–J’, L) and on both sides of the control molar (Fig 2, A–E’’, K–L). This suggests that autophagy plays a role in compression-related bone turnover or inflammation.

Figure 4. OTM is drastically reduced by autophagy gain of function with rapamycin.

[A-C] Schematic of orthodontic force application in mice with a split-mouth design. Occlusal view of the maxilla before [A] and after [C] placement of a NiTi coil spring on the experimental (E) side. The control (C) side has no spring placed and the molar remains unloaded. [B] 30 g of force measured by a force gauge prior to cementing the spring with light-cured composite resin. [D-I] 2D CT radiographs of control [D-F] and experimental [G-I] side molars. Left: mesial, compression side. Right: distal, tension side. Scale bar: 2 mm. [J-M] 2D CT radiographs of control [J-K] and experimental [L-M] side molars of mice injected with either saline vehicle or rapamycin. [N] OTM quantification at days post-loading in mice injected with saline vehicle or rapamycin. [O] Graph comparing OTM measured in μm of uninjected mice, saline vehicle injected mice and rapamycin injected mice.

An increase of LC3-autophagosome puncta indicates autophagy induction or downstream suppression.38 To confirm autophagic flux, molar PDL and surrounding alveolar bone were isolated for Western blot analysis of autophagy markers phospho-ULK1 and p62.38 With autophagy induction, phospho-ULK1 increases whereas p62 decreases or stabilizes as the pathway proceeds, as observed in our samples, consistent with autophagy activation occurring from day 1 onwards (Fig 2, M). Taken together, the increase in GFP-LC3+ puncta and phospho-ULK1 protein indicate autophagy is induced upon mechanical loading in vivo.

To gain mechanistic insight into autophagy’s role in OTM, we injected rapamycin, a well-known autophagy inducer. Rapamycin activates autophagy by inhibiting mTOR, the central suppressor of the autophagy pathway42; it is an Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved immunosuppressant. Administration of rapamycin increases autophagy activation, causing a statistically significant reduction in tooth movement compared to control groups (Fig 4, J–O). There is no statistically significant difference between the vehicle and no injection groups in amount of tooth movement (Fig 4, O). Data suggest that excess autophagy inhibits OTM, possibly through inhibition of the inflammatory cascade.

To evaluate correlation between autophagy and inflammation, we examined mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines (NFATC1, TNFα, Il-6, and Il-1β), bone turnover markers (RANKL, OPG and MMP9) and autophagy pathway genes (Becn1, LC3 and Atg5) in peri-dental tissues after force loading by qRT-PCR (Fig 3). Autophagy markers LC3 and ATG5 increased over time after loading, while BECN1 and inflammatory markers NFATC1, TNFα and IL-1β peaked early and then decreased (Fig 3, A–C, G–I). Bone turnover markers RANKL and MMP9 were upregulated after force loading, though MMP9 decreased following day 3 (Fig 3, D–F). However, Il-6 was not transcriptionally altered over time, consistent with published reports34,35; translational or post-translational variations may be occurring (Fig 3, J). Despite these trends, only some were statistically significant (Fig 3, A, D, F, and I), suggesting that regulation is also happening at a protein, rather than mRNA level. Our qPCR data (Fig 3) demonstrate a correlated increase in autophagy, inflammatory and bone turnover markers secondary to orthodontic loading.

Orthodontically loaded molars were TRAP stained to detect osteoclasts. Osteoclasts appear as early as day 3 on the compression side, with the highest levels detected at day 7 (Fig 5, E–H, Q). TRAP staining started decreasing towards baseline at day 10 post-loading (Fig 5, Q). No appreciable TRAP staining was found in the non-loaded controls (Fig 5, A–D and Q). Injection of rapamycin, an autophagy inducer, was associated with a significant decrease in osteoclasts relative to the vehicle (Fig 5, M–Q), suggesting that excess autophagy interferes with osteoclast recruitment. Lack of osteoclasts precludes bone resorption under compression, limiting OTM, as observed in rapamycin-treated mice (Fig 4, N–O).

Figure 5. Osteoclasts increase after orthodontic loading, but numbers are suppressed with rapamycin-mediated autophagy activation.

A-P, TRAP-stained sections. A-H, Saline vehicle injection. I-P, Rapamycin injection. Control: no loading. Experimental: loaded, 30g of force. Scale bar: 150 μm. Mesial, compression: left. Distal, tension: right. Q, Quantification of TRAP+ cells versus days post-loading (p<0.05).

Discussion

Our study is the first to tie orthodontic loading to activation of autophagy. OTM observed in our mouse line was consistent with published reports, with molar displacement linearly increasing over time.43 Force loaded molars demonstrate significantly more GFP-LC3 autophagosome puncta than controls, consistent with an increase in autophagic activity and confirmed by Western blot analysis of autophagy proteins phospho-ULK1 and p62 (Fig 2, M). GFP-LC3 puncta on the distal side of the root of the force loaded molar shows little change compared to the control molar, suggesting autophagy may play more of a role in bone resorption on the compression side than deposition on the distal/tension side. GFP-LC3 puncta and TRAP positive osteoclasts are higher on the compression side of the root, suggesting autophagy may act upstream of bone resorption.

Orthodontic force precedes increased compression-side osteoclasts, yet exposure to autophagy activator rapamycin causes a notable decrease in OTM and TRAP staining, relative to saline (Fig 4, J–O and Fig 5). Our data show excess autophagy inhibits OTM (Fig 4, J–O). Increasing evidence suggests a role of autophagy in negative regulation of inflammation in other organ systems during disease.11, 15,16,17,18 Therefore, we hypothesized a similar role of autophagy during OTM, through inhibition of the inflammatory cascade. Our qPCR data (Fig 3) show an increase in autophagy, inflammatory and bone turnover markers secondary to orthodontic loading. Orthodontic loading is associated with autophagy activation, aseptic inflammation, increased osteoclasts and bone turnover markers, while excess autophagy co-occurs with reduced tooth movement and osteoclasts, suggesting autophagy may play a role in regulation of inflammation and bone remodeling.

Controlled inflammation is critical during normal OTM, yet little is known about how it is regulated. Autophagy is a known modulator of inflammation whose dysregulation is tied to autoimmune diseases.15,16,17,18 We are the first to present data correlating autophagic activity with inflammation during tooth movement. Changes of autophagy occur at the mRNA level and at the translational/post-translational level, similar to what has been found in other systems.34,35

To explore whether autophagy modulates inflammation during OTM, we administered rapamycin, an FDA-approved autophagy inducer, to orthodontically loaded mice. We hypothesized that if autophagy reduces inflammation, OTM will slow after autophagy induction, as inflammation is requisite for tooth movement. Indeed, we observed reduced OTM with autophagy activation, suggesting it may downregulate inflammation during OTM. An alternate hypothesis is that autophagy directly inhibits bone turnover, limiting OTM. Our data show an increase in TRAP positive osteoclasts under compression that fails to occur with rapamycin-induced autophagy. Our qPCR and TRAP data do not tease apart these two hypotheses, as findings are consistent with autophagy impacting inflammation and bone turnover, as processes occurring in parallel or in series. Further analyses are needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanism of autophagy’s role in OTM, including loss of function, cell-specific and molecular studies.

This study adds to the growing literature tying autophagy to bone turnover and is the first to identify a role for autophagy in the mouth and dentition.26,27,28 Studies identified basal autophagy levels in the developing teeth and the adult dentition, though its functions were unknown.29,30,31 Our data suggest autophagy acts upstream of bone turnover and inflammatory cascades in the mouth. This finding may have far-reaching implications for how autophagy influences tissue remodeling and inflammation in the contexts of orthodontics, periapical lesions, periodontal disease and its systemic sequelae, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.17,33,44

By testing FDA-approved modulators of autophagy during OTM, we are working towards interventions in which noninvasive, localized drug delivery could accelerate tooth movement to shorten treatment or reversibly halt movement for anchorage reinforcement. Furthermore, modulating autophagy and inflammation may provide novel targets for treating oral diseases associated with excess inflammation such as periodontitis and orthodontic-induced apical root resorption.42 Understanding autophagy’s role in the dentition holds great potential, and our study provides the first insights into this exciting future.

Conclusions

Autophagy is activated in peri-dental tissues by orthodontic loading.

Autophagic activity is correlated with inflammatory markers after force application.

Rapamycin, an autophagy inducer, reduces tooth movement and osteoclasts, suggesting autophagy downregulates inflammation or bone turnover during tooth movement.

Highlights.

- Autophagy is activated in peri-dental tissues by orthodontic loading.

- Autophagic activity correlates with inflammatory markers after force application.

- Rapamycin, an autophagy inducer, reduces tooth movement and osteoclast recruitment.

- Data suggest autophagy decreases inflammation and bone turnover after tooth loading.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Pablo Ariel and the excellent staff of the UNC Microscopy Services Laboratory for their guidance and instruction. We want to acknowledge John Whitley and other members of the Ko lab for their support and assistance.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant #R01DE022816] and the UNC Hale Professorship fund. This work was also supported by the American Association of Orthodontics Foundation (AAOF) Martin ‘Bud’ Schulman Postdoctoral Fellowship awarded to Dr. Jacox. Drs. Li and Jacox were supported by the Graduate School Masters Merit Assistantship for study in Dentistry awarded by the UNC Graduate School, the Southern Association of Orthodontics (SAO) research awards, and the Masters Research Support Grants awarded by the Office of the Associate Dean for Research at UNC School of Dentistry and the Dental Foundation of North Carolina.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Koyama Y, Mitsui N, Suzuki N, et al. Effect of compressive force on the expression of inflammatory cytokines and their receptors in osteoblastic Saos-2 cells. Arch. Oral Biol 2008;53(5):488–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade IJ, Silva TA, Silva GAB, Teixeira AL, Teixeira MM. The role of tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 in orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Res 2007;86(11):1089–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda A, Soejima K, Bandow K, et al. Force-induced IL-8 from periodontal ligament cells requires IL-1beta. J. Dent. Res 2007;86(7):629–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi M, Yoshii M, Kasai K. Relationship between substance P and interleukin-1beta in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement in adults. Eur. J. Orthod 2006;28(3):241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguchi M, Ozawa Y, Mishima H, Aihara N, Kojima T, Kasai K. Substance P increases production of proinflammatory cytokines and formation of osteoclasts in dental pulp fibroblasts in patients with severe orthodontic root resorption. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop 2008;133(5):690–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diercke K, Kohl A, Lux CJ, Erber R. IL-1β and compressive forces lead to a significant induction of RANKL-expression in primary human cementoblasts. J. Orofac. Orthop 2012;73(5):397–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakao K, Goto T, Gunjigake KK, Konoo T, Kobayashi S, Yamaguchi K. Intermittent force induces high RANKL expression in human periodontal ligament cells. J. Dent. Res 2007;86(7):623–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi M. RANK/RANKL/OPG during orthodontic tooth movement. Orthod. Craniofac. Res 2009;12(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan V, Davidovitch Z. Cellular, molecular, and tissue-level reactions to orthodontic force. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129(4):469.e1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H, Williams RC, Kyrkanides S. Accelerated orthodontic tooth movement: molecular mechanisms. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop 2014;146(5):620–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee B. Force and tooth movement. Aust. Orthod. J 2007;23(2):155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan V, Davidovitch Z. On a path to unfolding the biological mechanisms of orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Res 2009;88(7):597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garlet TP, Coelho U, Silva JS, Garlet GP. Cytokine expression pattern in compression and tension sides of the periodontal ligament during orthodontic tooth movement in humans. Eur. J. Oral Sci 2007;115(5):355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM. Contemporary orthodontics. St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Mosby; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez J, Cunha LD, Park S, et al. Noncanonical autophagy inhibits the autoinflammatory, lupus-like response to dying cells. Nature 2016;533(7601):115–9. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27096368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Yang Z, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Autophagy in autoimmune disease. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2015;93(7):707–17. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26054920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bullon P, Cordero MD, Quiles JL, et al. Autophagy in periodontitis patients and gingival fibroblasts: unraveling the link between chronic diseases and inflammation. BMC Med. 2012;10:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Netea-Maier RT, Plantinga TS, van de Veerdonk FL, Smit JW, Netea MG. Modulation of inflammation by autophagy: Consequences for human disease. Autophagy 2016;12(2):245–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 2011;27:107–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Pathol 2010;221(1):3–12. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20225336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu WJ, Ye L, Huang WF, et al. p62 links the autophagy pathway and the ubiqutin--proteasome system upon ubiquitinated protein degradation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett 2016;21(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature 2008;456(7219):264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crisan TO, Plantinga TS, van de Veerdonk FL, et al. Inflammasome-independent modulation of cytokine response by autophagy in human cells. PLoS One 2011;6(4):e18666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris J. Autophagy and cytokines. Cytokine 2011;56(2):140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapaquette P, Guzzo J, Bretillon L, Bringer M-A. Cellular and Molecular Connections between Autophagy and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:398483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambandam Y, Townsend MT, Pierce JJ, et al. Microgravity control of autophagy modulates osteoclastogenesis. Bone 2014;61:125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin N-Y, Beyer C, Giessl A, et al. Autophagy regulates TNFalpha-mediated joint destruction in experimental arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis 2013;72(5):761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nollet M, Santucci-Darmanin S, Breuil V, et al. Autophagy in osteoblasts is involved in mineralization and bone homeostasis. Autophagy 2014;10(11):1965–77. Available at: 10.4161/auto.36182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Couve E, Osorio R, Schmachtenberg O. The amazing odontoblast: activity, autophagy, and aging. J. Dent. Res 2013;92(9):765–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Zhu L, Yuan G, et al. Autophagy appears during the development of the mouse lower first molar. Histochem. Cell Biol 2013;139(1):109–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang J, Wan C, Nie S, et al. Localization of Beclin1 in mouse developing tooth germs: possible implication of the interrelation between autophagy and apoptosis. J. Mol. Histol 2013;44(6):619–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuang H, Hu D, Singer D, et al. Local anesthetics induce autophagy in young permanent tooth pulp cells. Cell Death Discov. 2015;1:15024. Available at: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuang H, Ali K, Ardu S, Tredwin C, Hu B. Autophagy in dental tissues: a double-edged sword. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(4):e2192–e2192. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27077808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004;15(3):1101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodrum C, Nobil A, Dabora SL. Comparison of three rapamycin dosing schedules in A/J Tsc2+/− mice and improved survival with angiogenesis inhibitor or asparaginase treatment in mice with subcutaneous tuberous sclerosis related tumors. Journal of Translational Medicine 2010, 8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao W, Li S, Pacios S, Wang Y, Graves DT. Bone Remodeling Under Pathological Conditions. In: Frontiers of oral biologyVol 18.; 2016:17–27. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26599114. Accessed March 7, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang X, Kalajzic Z, Maye P, et al. Histological analysis of GFP expression in murine bone. J. Histochem. Cytochem 2005;53(5):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taddei SR de A, Moura AP, Andrade IJ, et al. Experimental model of tooth movement in mice: a standardized protocol for studying bone remodeling under compression and tensile strains. J. Biomech 2012;45(16):2729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apelo SIA, Neuman JC, Baar EL, Syed FA, Cummings NE, Brar HK, Pumper CP, Kimple ME, Lamming DW. Alternative rapamycin treatment regimens mitigate the impact of rapamycin on glucose homeostasis and the immune system. Aging Cell 2016, 15: 28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenney DL, Benarroch EE. The autophagy-lysosomal pathway. Neurology 2015;85(7):634–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Tor, a phosphatidylinositol kinase homologue, controls autophagy in yeast. J. Biol. Chem 1998;273(7):3963–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tyrovola JB, Odont X. The “Mechanostat Theory” of Frost and the OPG/RANKL/RANK System. J. Cell. Biochem 2015;116(12):2724–9. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26096594. Accessed March 7, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan Y-Q, Zhang J, Zhou G. Autophagy and its implication in human oral diseases. Autophagy 2017;13(2):225–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]