Abstract

Burn prevention programs can effectively reduce morbidity and mortality rates. In this article, we present the findings of our investigation of the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Saudi Arabian population regarding electrical burns. Our study was a cross-sectional online survey that used a five-part questionnaire to assess the participant’s demographic information, knowledge of electrical burns, attitudes toward electrical injuries, and practices related to electrical burns and their prevention. Overall, 2314 individuals responded to the survey (males: 41.2%; females: 58.8%). A total of 839 participants (36%) had a personal or family history of electrical burns. Approximately ≥90% of the responses to questions on electrical burn-related knowledge were correct; relatively less responses to questions on the extent of tissue damage from electrical burns and arcs were correct (74% and 29%, respectively). Only 54% of the respondents knew that applying first aid to the burn-affected areas at home could lead to a better outcome; 27% and 19% did not know the correct answer and thought that this would not lead to a better outcome, respectively. The most common source of information was school or college (38.9%), followed by social media (20.8%) and internet websites (16.3%). Enhancing community awareness and practices related to electrical burns is a cost-effective and straightforward strategy to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with electrical injuries.

Keywords: knowledge, attitudes, practices, electrical burn, Saudi Arabia

BACKGROUND

Burn injuries have been prevalent throughout the course of human civilization. They represent a significant public health challenge worldwide with catastrophic consequences.1,2

Burns can result from a variety of sources, including exposure to dry or moist heat, chemicals, friction, electricity, and extremely cold conditions. A comprehensive analysis of burn-related epidemiological patterns is imperative for the effective implementation of burn prevention strategies and resource allocation.

Electrical injuries are sustained when an individual comes in contact with an electrical source either directly or indirectly (ie, through a conductive material).3 Upon contact, a high-energy current passes through their body, and injuries arise from this passage of current or from arc flashes: the electrical energy is converted into heat, which results in a thermal burn that is one of the three basic bioeffects of electrical injury with pure electrical forces and the action of ionized molecules.4 Notably, The external appearance of an electrical injury may not reflect the underlying tissue damage; compared to the skin, internal organs or tissues may suffer more severe burns. Therefore, it is essential to consider the potential for deeper tissue injuries when assessing electrical injury.

Electrical injury requires distinctive consideration because of the associated elevated incidence of complications, such as amputations, compartment syndrome, and mortality. Notably, electric injuries account for approximately 0.8%–1% of all unintentional fatalities.5

Approximately 4%–5% of all burn cases managed in medical facilities are attributed to electrical burns.5 Approximately 1000 electrical injury-related deaths occur in the United States; furthermore, accidental high-voltage electrical injuries account for approximately 400 fatalities in the country annually. Occupational electrical injuries are more frequent among adults, whereas household electrical injuries are more frequent among children. Furthermore, the incidence of electrical injuries is higher among males than among females.6

In Saudi Arabia, electrical injuries account for 9.48% of all admissions to the burns units.7 Electrical burns are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. However, preventive measures can be readily implemented, with education and policy implementation being deemed crucial strategies for reducing the incidence of electrical injuries.

This study aimed to evaluate the level of knowledge and practices concerning electrical burns and first-aid measures in Saudi Arabia as well as determine the primary sources of information accessed by individuals in relation to this topic especially those that have not been studied before in Saudi Arabia.

METHODS

Data collection

This was a cross-sectional study and used a five-part questionnaire that was disseminated over a 6-week period through various social media platforms to assess (1) demographic information, (2) knowledge of electrical burns, (3) attitudes toward electrical injuries, (4) practices related to electrical burns and their prevention, and (5) referred sources of information on electrical burns were disseminated to the participants in an online survey among individuals aged ≥15 years in Saudi Arabia. Study participation was voluntary, and all included individuals agreed to participate. The questionnaire responses were anonymous.

Data collection tool

A standardized questionnaire was developed in Arabic. To ensure its validity, the questionnaire was reviewed by four expert plastic surgeons and piloted in 20 volunteers. Following feedback from the pilot study, the questionnaire was modified to include a clear explanation of the study’s aims and a statement of voluntary participation at the beginning. The questionnaire comprised five sections. The first section examined the responder’s demographic information. The second section focused on the responder’s knowledge of electrical burns. The third section examined the responder’s attitudes toward electrical injuries. The fourth section explored the responder’s practices related to the treatment and prevention of electrical burns. Finally, the fifth section examined the primary sources of information on electrical injuries that the responders accessed. The survey was conducted in Arabic to enhance public accessibility and comprehensibility. Subsequently, the responses were translated into English using accredited translation service to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Statistical analysis

Data management and statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (version 1.2.5042; Boston, MA, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, and mean with standard deviation) were calculated as required. The Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests revealed that the data were non-normally distributed. Thus, non-parametric tests (such as the Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney U tests) were used to determine the relationships among sociodemographic characteristics and safety precautions.

Bonferroni adjustment was used to alter the P values in a post-hoc test (Dunn’s test). Spearman’s rank correlation and logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the associations in the knowledge, attitudes, and practices domains. The total scores for knowledge, attitude, and practice were calculated by summing the scores for each item. Subsequently, depending on an 80% cutoff point, replies were rated as “good” or “bad” and labeled 1 and 0, respectively. Thereafter, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the factors associated with electrical burn-related knowledge (five questions), attitudes (three questions), and practices. Only the relevant univariate variables were included in the multiple logistic regression analysis after screening. A 95% CI was calculated for all statistical investigations.

RESULTS

The questionnaire was completed by 2314 respondents; their characteristics are presented in Table 1. Males and females comprised 41.2% and 58.8% of the study sample, respectively. Respondents aged 19–35 years represented one-third of the study sample (35.1%); those aged ≥31 years represented another one-third of the study sample. More than 50% of the respondents had obtained a university degree (59.5%), whereas 8.51% had obtained a postgraduate degree. Respondents from the Central, Eastern, Western, Northern, and Southern regions accounted for approximately 50%, 16.6%, 15.8%, 10.8%, and 8.08% of the study sample, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Study Sample

| [ALL] | |

|---|---|

| N = 2314 | |

| Age (years) | |

| 15–18 | 224 (9.68%) |

| 19–25 | 812 (35.1%) |

| 26–30 | 423 (18.3%) |

| 31–35 | 287 (12.4%) |

| 36–45 | 340 (14.7%) |

| >45 | 228 (9.85%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 1 360 (58.8%) |

| Male | 954 (41.2%) |

| Nationality | |

| Non-Saudi | 217 (9.38%) |

| Saudi | 2 097 (90.6%) |

| Region | |

| Central | 1 125 (48.6%) |

| Eastern | 385 (16.6%) |

| Northern | 251 (10.8%) |

| Southern | 187 (8.08%) |

| Western | 366 (15.8%) |

| Education | |

| Lower than high school | 83 (3.59%) |

| High school | 421 (18.2%) |

| Diploma | 236 (10.2%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 377 (59.5%) |

| MSc or PhD degree | 197 (8.51%) |

| Monthly income | |

| <5 000 SAR | 1 026 (44.3%) |

| >20 000 SAR | 140 (6.05%) |

| 10 000–20 000 SAR | 578 (25.0%) |

| 5 000–10 000 SAR | 570 (24.6%) |

Data are expressed as counts and percentages.

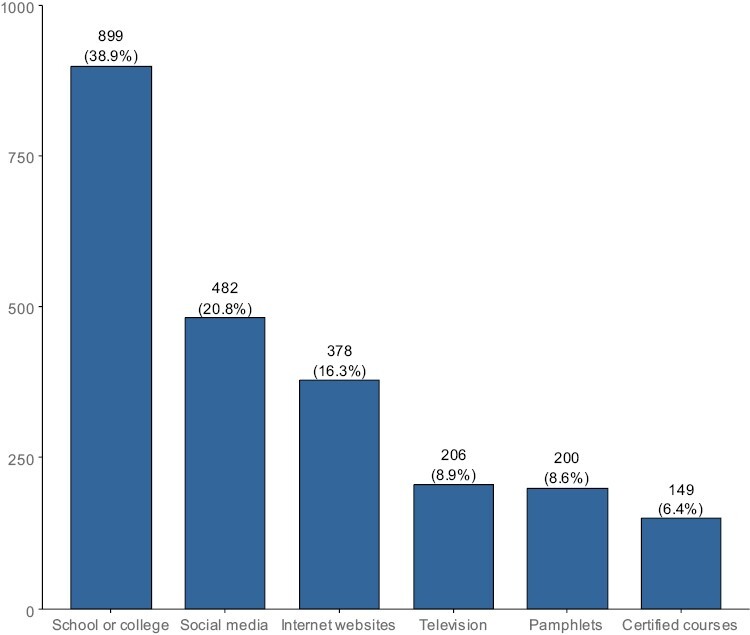

A total of 839 participants (36%) had a personal or family history of electrical burns. The most common source of information was school or college (38.9%), followed by social media (20.8%) and websites (16.3%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sources of Information for the Respondents

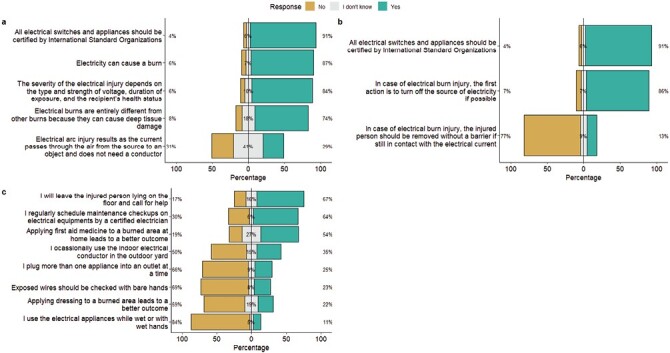

Approximately ≥90% of the responses for almost all questions on knowledge were correct; however, relatively lesser responses to the questions correctly on the extent of tissue damage from electrical burns and arcs were correct (74% and 29%, respectively). For questions on attitudes, approximately ≥90% of the responses were correct. However, conflicting results were observed for questions on practices. Only 54% of the respondents knew that administering first aid to burn-affected areas at home could lead to a better outcome; 27% and 19% of the remaining responders did not know the correct answer and thought that it would not lead to a better outcome, respectively (Table 2). Interestingly, 54.32%of the respondents believed that applying dressing to burn-affected areas could lead to a better outcome. Furthermore, 24.81% of the respondents also disclosed plugging multiple appliances into power outlets simultaneously. One-third of the respondents reported using an indoor electric conductor in an outdoor yard (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Responses to Questions on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices

| Response | 95% CI for the correct answer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | I do not know | Yes | ||

| Knowledge | ||||

| Electricity can cause a burn | 137 (5.92%) | 162 (7.00%) | 2015 (87.08%)a | 87.08 (85.64–88.42) |

| Electrical burns are entirely different from other burns because they can cause deep-tissue damage | 189 (8.17%) | 417 (18.02%) | 1708 (73.81%)a | 73.81 (71.97–75.59) |

| The severity of the electrical injury depends on the type and strength of voltage, duration of exposure, and the recipient’s health status | 141 (6.09%) | 225 (9.72%) | 1948 (84.18%)a | 84.18 (82.63–85.65) |

| Attitude | ||||

| Electrical arc injury is sustained when the current from the source passes through the air and does not require a conductor | 706 (30.51%) | 946 (40.88%) | 662 (28.61%)a | 28.61 (26.77–30.5) |

| All electrical switches and appliances installed at homes and offices should be certified by an International Standard Organization | 87 (3.76%) | 128 (5.53%) | 2099 (90.71%)a | 90.71 (89.45–91.86) |

| In case of an electrical burn injury, the first action is to turn off the source of electricity if possible | 163 (7.04%) | 158 (6.83%) | 1993 (86.13%)a | 86.13 (84.65–87.51) |

| Practices | ||||

| In case of an electrical burn injury, the injured person should be moved away without a barrier if still in contact with the electrical current | 1786 (77.18%)a | 216 (9.33%) | 312 (13.48%) | 77.18 (75.42–78.88) |

| The injured person is to be left lying on the floor while help is called for | 392 (16.94%) | 363 (15.69%) | 1559 (67.37%)a | 67.37 (65.42–69.28) |

| Administering first aid to the burn-affected areas at home leads to a better outcome | 432 (18.67%) | 625 (27.01%) | 1257 (54.32%)a | 54.32 (52.27–56.37) |

| Applying dressing to the burn-affected area leads to a better outcome | 1368 (59.12%)a | 439 (18.97%) | 507 (21.91%) | 59.12 (57.08–61.13) |

| I plug more than one appliance into an outlet simultaneously | 1526 (65.95%)a | 214 (9.25%) | 574 (24.81%) | 65.95 (63.97–67.88) |

| I occasionally use the indoor electrical conductor in an outdoor yard | 1162 (50.22%)a | 345 (14.91%) | 807 (34.87%) | 50.22 (48.16–52.27) |

| Exposed wires should be checked with bare hands | 1600 (69.14%)a | 176 (7.61%) | 538 (23.25%) | 69.14 (67.22–71.02) |

| I use electrical appliances while wet or with wet hands | 1953 (84.40%)a | 111 (4.80%) | 250 (10.80%) | 84.4 (82.86–85.86) |

| I regularly maintenance check-ups of electrical equipment by a certified electrician should be scheduled regularly | 698 (30.16%) | 132 (5.70%) | 1484 (64.13%)a | 64.13 (62.14–66.09) |

aCorrect answer.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Responses to Questions on (A) Knowledge, (B) Attitudes, and (C) Practices Regarding Electrical Burns

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electrical burns and their prevention showed a significantly increasing linear trend with increasing age (P < .001). The respondents’ sex and nationality were not significantly associated with their knowledge and attitudes (P > .05). However, these factors were significantly associated with their practices (odds ratio [OR] = 0.69, P < .001), with the practices being worse among males than among females. The odds of possessing a good knowledge of electrical burns were significantly lower among respondents from the Eastern region than among those from the Central region (OR = 0.62, P < .001). The odds of having a correct attitude towards electrical burns were significantly lower in respondents from regions other than the Central region. The odds of engaging in good practices regarding electrical burns did not differ significantly among the respondents from all tested regions.

Education was significantly associated with electrical burn-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Respondents with a high school level or lower level of education had a lower odds of both possessing good knowledge (OR = 0.37, P < .001) and attitude (OR = 0.59, P < .001) as well as engaging in good practices (OR = 0.53, P < .001) regarding electrical burns. Conversely, these odds did not differ significantly between respondents who had obtained a diploma and those who had obtained a bachelor’s degree. In comparison with those who attained university education, respondents who had attained a postgraduate degree had significantly higher odds of possessing good knowledge (OR = 1.75, P = .003) and attitude (OR = 1.4, P = .028) regarding electrical burns. Multivariate analysis revealed that income was not associated with the odds of possessing good knowledge and scores or of engaging in good practices regarding electrical burns. A personal or family history of electrical injuries was associated with a lower odds of having knowledge (OR = 0.67, P < .001) and a positive attitude (OR = 0.79, P < .001) toward electric burns (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices

| [ALL] | |

|---|---|

| N = 2314 | |

| Knowledge score | 3.64 (1.12) |

| Attitude score | 2.31 (0.81) |

| Practice score | 4.47 (1.67) |

| Knowledge | |

| Bad | 755 (32.6%) |

| Good | 1 559 (67.4%) |

| Attitude | |

| Bad | 1 167 (50.4%) |

| Good | 1 147 (49.6%) |

| Practice | |

| Bad | 1 590 (68.7%) |

| Good | 724 (31.3%) |

Good was defined as a score of >80%.

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Electrical Burns

| Knowledge | Attitudes | Practices | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bad | Good | OR | P values | Bad | Good | OR | P values | Bad | Good | OR | P values | |

| N = 755 | N = 1559 | N = 1 167 | N = 1147 | N = 1 590 | N = 724 | |||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–18 | 140 (62.5%) | 84 (37.5%) | Ref. | Ref. | 154 (68.8%) | 70 (31.2%) | Ref. | Ref. | 187 (83.5%) | 37 (16.5%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 19–25 | 258 (31.8%) | 554 (68.2%) | 3.57 [2.63; 4.88] | .000 | 428 (52.7%) | 384 (47.3%) | 1.97 [1.44; 2.71] | <.001 | 599 (73.8%) | 213 (26.2%) | 1.79 [1.23; 2.67] | .002 |

| 26–30 | 124 (29.3%) | 299 (70.7%) | 4.01 [2.85; 5.66] | <.001 | 201 (47.5%) | 222 (52.5%) | 2.42 [1.73; 3.42] | <.001 | 279 (66.0%) | 144 (34.0%) | 2.60 [1.75; 3.95] | <.001 |

| 31–35 | 82 (28.6%) | 205 (71.4%) | 4.15 [2.87; 6.05] | <.001 | 141 (49.1%) | 146 (50.9%) | 2.27 [1.58; 3.29] | <.001 | 196 (68.3%) | 91 (31.7%) | 2.34 [1.53; 3.64] | <.001 |

| 36–45 | 86 (25.3%) | 254 (74.7%) | 4.90 [3.41; 7.09] | .000 | 141 (41.5%) | 199 (58.5%) | 3.10 [2.18; 4.44] | <.001 | 204 (60.0%) | 136 (40.0%) | 3.35 [2.23; 5.13] | <.001 |

| > 45 | 65 (28.5%) | 163 (71.5%) | 4.16 [2.81; 6.21] | <.001 | 102 (44.7%) | 126 (55.3%) | 2.71 [1.85; 4.00] | <.001 | 125 (54.8%) | 103 (45.2%) | 4.14 [2.69; 6.49] | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 444 (32.6%) | 916 (67.4%) | Ref. | Ref. | 692 (50.9%) | 668 (49.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | 890 (65.4%) | 470 (34.6%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 311 (32.6%) | 643 (67.4%) | 1.00 [0.84; 1.20] | .982 | 475 (49.8%) | 479 (50.2%) | 1.04 [0.89; 1.23] | .605 | 700 (73.4%) | 254 (26.6%) | 0.69 [0.57; 0.82] | <.001 |

| Nationality | ||||||||||||

| Non-Saudi | 73 (33.6%) | 144 (66.4%) | Ref. | Ref. | 102 (47.0%) | 115 (53.0%) | Ref. | Ref. | 156 (71.9%) | 61 (28.1%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Saudi | 682 (32.5%) | 1415 (67.5%) | 1.05 [0.78; 1.41] | .734 | 1065 (50.8%) | 1032 (49.2%) | 0.86 [0.65; 1.14] | .290 | 1434 (68.4%) | 663 (31.6%) | 1.18 [0.87; 1.62] | .290 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Central | 336 (29.9%) | 789 (70.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | 499 (44.4%) | 626 (55.6%) | Ref. | Ref. | 771 (68.5%) | 354 (31.5%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Eastern | 157 (40.8%) | 228 (59.2%) | 0.62 [0.49; 0.79] | <.001 | 230 (59.7%) | 155 (40.3%) | 0.54 [0.42;0.68] | <.001 | 278 (72.2%) | 107 (27.8%) | 0.84 [0.65; 1.08] | .176 |

| Northern | 75 (29.9%) | 176 (70.1%) | 1.00 [0.74; 1.35] | .991 | 143 (57.0%) | 108 (43.0%) | 0.60 [0.46; 0.79] | <.001 | 168 (66.9%) | 83 (33.1%) | 1.08 [0.80; 1.44] | .620 |

| Southern | 61 (32.6%) | 126 (67.4%) | 0.88 [0.63; 1.23] | .447 | 109 (58.3%) | 78 (41.7%) | 0.57 [0.42; 0.78] | <.001 | 127 (67.9%) | 60 (32.1%) | 1.03 [0.74; 1.43] | .861 |

| Western | 126 (34.4%) | 240 (65.6%) | 0.81 [0.63; 1.04] | .103 | 186 (50.8%) | 180 (49.2%) | 0.77 [0.61; 0.98] | .032 | 246 (67.2%) | 120 (32.8%) | 1.06 [0.82; 1.37] | .636 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 388 (28.2%) | 989 (71.8%) | Ref. | Ref. | 660 (47.9%) | 717 (52.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | 920 (66.8%) | 457 (33.2%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Diploma | 70 (29.7%) | 166 (70.3%) | 0.93 [0.69; 1.26] | .637 | 121 (51.3%) | 115 (48.7%) | 0.87 [0.66; 1.15] | .344 | 151 (64.0%) | 85 (36.0%) | 1.13 [0.85; 1.51] | .396 |

| High school or lower | 261 (51.8%) | 243 (48.2%) | 0.37 [0.30; 0.45] | .000 | 308 (61.1%) | 196 (38.9%) | 0.59 [0.48; 0.72] | <.001 | 399 (79.2%) | 105 (20.8%) | 0.53 [0.41; 0.67] | <.001 |

| Postgraduation (Master’s degree or Doctor of Philosophy degree) | 36 (18.3%) | 161 (81.7%) | 1.75 [1.21; 2.59] | .003 | 78 (39.6%) | 119 (60.4%) | 1.40 [1.04; 1.91] | .028 | 120 (60.9%) | 77 (39.1%) | 1.29 [0.95; 1.75] | .105 |

| Monthly income | ||||||||||||

| <5000 SAR | 398 (38.8%) | 628 (61.2%) | Ref. | Ref. | 557 (54.3%) | 469 (45.7%) | Ref. | Ref. | 751 (73.2%) | 275 (26.8%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 5000–10 000 SAR | 157 (27.5%) | 413 (72.5%) | 1.67 [1.34; 2.08] | <.001 | 268 (47.0%) | 302 (53.0%) | 1.34 [1.09; 1.64] | .005 | 382 (67.0%) | 188 (33.0%) | 1.34 [1.07; 1.68] | .010 |

| 10 000–20 000 SAR | 158 (27.3%) | 420 (72.7%) | 1.68 [1.35; 2.11] | <.001 | 270 (46.7%) | 308 (53.3%) | 1.35 [1.10; 1.66] | .004 | 364 (63.0%) | 214 (37.0%) | 1.61 [1.29; 2.00] | <.001 |

| > 20 000 SAR | 42 (30.0%) | 98 (70.0%) | 1.48 [1.01; 2.18] | .043 | 72 (51.4%) | 68 (48.6%) | 1.12 [0.79; 1.60] | .525 | 93 (66.4%) | 47 (33.6%) | 1.38 [0.94; 2.01] | .098 |

| History of electrical injury | ||||||||||||

| No | 434 (29.4%) | 1041 (70.6%) | Ref. | Ref. | 712 (48.3%) | 763 (51.7%) | Ref. | Ref. | 1007 (68.3%) | 468 (31.7%) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 321 (38.3%) | 518 (61.7%) | 0.67 [0.56; 0.80] | <.001 | 455 (54.2%) | 384 (45.8%) | 0.79 [0.66; 0.93] | .006 | 583 (69.5%) | 256 (30.5%) | 0.95 [0.79; 1.13] | .545 |

Analysis was performed using univariate logistic regression.

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Multivariate analysis yielded findings that were similar to those of the univariate analysis (Table 5). The knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electrical burns showed a significantly increasing linear trend with increasing age (P < .001). The respondents’ sex and nationality were not significantly associated with their knowledge and attitudes (P > .05); however, these factors were significantly associated with their practices (OR = 0.7, P < .001), with males having worse practices than females. The region of residence was not significantly associated with the odds of possessing good knowledge and attitudes or of engaging in good practices regarding electrical burns. Conversely, education was significantly associated with the respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Those with a high school level or lower level of education had a lower odds of both possessing good knowledge (OR = 0.5, P < .001) and attitude (OR = 0.7, P < .001) and of engaging in good practices (OR = 0.6, P < .001) regarding electrical burns. The odds did not differ significantly between respondents who had obtained a diploma and those who had attained a Bachelor’s degree. Compared with those who had attained university education, respondents who had obtained a postgraduate degree had a significantly higher odds of possessing good knowledge (OR = 1.79, P = .005) regarding electric burns. A higher income was not associated with the odds of possessing a good knowledge and scores or of engaging in good practices regarding electrical burns. A personal or family history of electrical injuries was associated with a lower odds of possessing knowledge (OR = 0.74, P = .002) and a good attitudes (OR = 0.84, P < .049) toward electric burns.

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Electrical Burns

| Good knowledge | Good attitude | Good practice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds ratios | CI | P | Odds ratios | CI | P | Odds ratios | CI | P |

| Age: 15–18 years | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Age: 19–25 years | 2.19 | 1.54–3.13 | <.001 | 1.47 | 1.03–2.11 | .037 | 1.31 | 0.85–2.04 | .231 |

| Age: 26–30 years | 2.10 | 1.39–3.17 | <.001 | 1.88 | 1.26–2.83 | .002 | 1.95 | 1.22–3.15 | .006 |

| Age: 31–35 years | 2.26 | 1.47–3.51 | <.001 | 1.87 | 1.22–2.87 | .004 | 1.77 | 1.08–2.93 | .024 |

| Age: 36–45 years | 2.65 | 1.72–4.10 | <.001 | 2.54 | 1.67–3.89 | <.001 | 2.48 | 1.54–4.06 | <.001 |

| Age: >45 years | 2.40 | 1.52–3.80 | <.001 | 2.11 | 1.35–3.29 | .001 | 3.28 | 1.99–5.46 | <.001 |

| Female | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Male | 0.98 | 0.81–1.19 | .860 | 1.01 | 0.85–1.20 | .941 | 0.70 | 0.57–0.84 | <.001 |

| <5 000 SAR | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 5 000–10 000 SAR | 1.17 | 0.90–1.51 | .240 | 0.96 | 0.76–1.22 | .760 | 0.92 | 0.71–1.18 | .503 |

| 10 000–20 000 SAR | 1.02 | 0.77–1.37 | .878 | 0.90 | 0.69–1.17 | .417 | 0.91 | 0.69–1.21 | .532 |

| >20 000 SAR | 0.85 | 0.55–1.33 | .472 | 0.71 | 0.47–1.07 | .105 | 0.83 | 0.53–1.28 | .402 |

| Non-Saudi | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Saudi | 1.15 | 0.84–1.56 | .385 | 0.99 | 0.74–1.32 | .939 | 1.30 | 0.94–1.80 | .114 |

| Central | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Eastern | 0.77 | 0.59–1.00 | .050 | 0.60 | 0.47–0.77 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.72–1.25 | .721 |

| Northern | 0.99 | 0.72–1.36 | .931 | 0.57 | 0.43–0.76 | <.001 | 0.90 | 0.66–1.22 | .497 |

| Southern | 0.82 | 0.58–1.17 | .265 | 0.55 | 0.40–0.76 | <.001 | 0.98 | 0.70–1.38 | .924 |

| Western | 0.84 | 0.65–1.09 | .189 | 0.81 | 0.63–1.03 | .082 | 1.14 | 0.87–1.47 | .344 |

| Bachelor’s degree | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Diploma | 0.88 | 0.65–1.21 | .421 | 0.83 | 0.62–1.10 | .198 | 1.02 | 0.75–1.37 | .901 |

| High school or lower | 0.50 | 0.39–0.64 | <.001 | 0.70 | 0.55–0.89 | .004 | 0.60 | 0.45–0.79 | <.001 |

| Postgraduation (Master’s degree or Doctor of Philosophy degree) | 1.79 | 1.20–2.72 | .005 | 1.32 | 0.94–1.85 | .110 | 1.11 | 0.78–1.55 | .564 |

| Electrical injury: No | |||||||||

| Electrical injury: Yes | 0.74 | 0.61–0.90 | .002 | 0.84 | 0.70–1.00 | .049 | 1.01 | 0.83–1.23 | .907 |

| R2 Tjur | 0.069 | 0.041 | 0.044 | ||||||

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

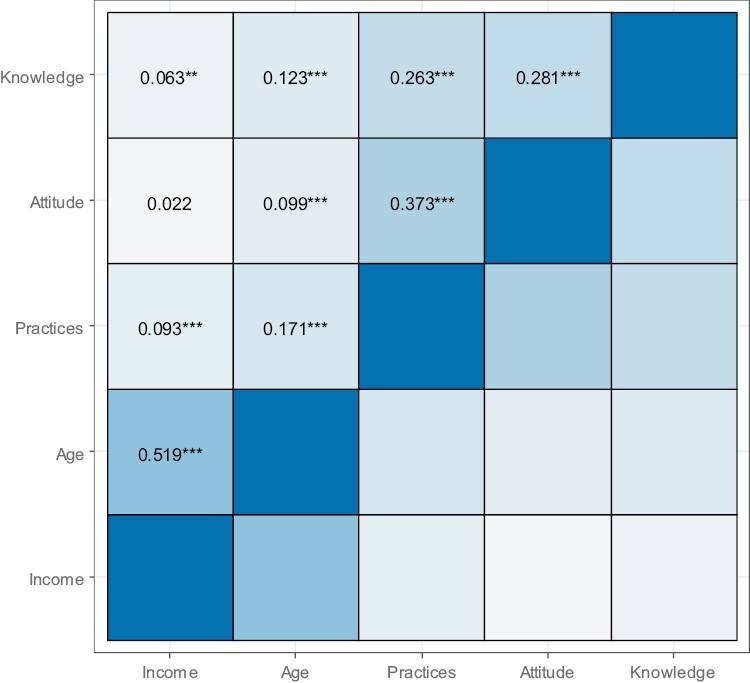

Statistically significant associations were observed between knowledge and practices (r = 0.263, P < .001), attitudes and practices (r = 0.373, P < .001), and knowledge and attitudes (r = 0.281, P < .001). Very weak correlations were also observed between age and knowledge of electrical burns (r = 0.123, P < .001) and between income and knowledge (r = 0.063, P < .01). No association was observed between attitudes and income (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation among Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Electrical Burns

DISCUSSION

Electrical injuries are distinct from other forms of burns because of their ability to induce profound tissue damage beyond what is visible on the skin. An electrical injury can be direct or indirect. The mechanism of direct injury and nature were caused by the strong electrical field which depends on the duration of exposure, frequency, and field strength. While the indirect one is mediated through electrophysiologic responses.4

Neurological trauma is the primary complication of electrical burns.8 One study demonstrated that high-voltage electrical burns are linked to devastating consequences, such as the need for limb amputation.9

Due to insufficient research on the general public’s awareness and mindset towards electrical burn injuries, our study was designed to explore the level of knowledge and attitudes toward electrical burns in the Saudi Arabian population; 839 (36%) participants of our survey had a personal or family history of electrical burns.

Our study revealed that approximately ≥90% of the responses to questions related to knowledge of electrical burns were accurate. However, relatively less responses to questions pertaining to the extent of tissue damage caused by electrical burns and arcs were accurate (74% and 29%, respectively).

Approximately ≥90% of the responses to questions on the attitudes towards electrical burns were accurate in our study. However, contrasting outcomes were noted in responses to questions on practices regarding electrical burns; specifically, only 54% of the respondents were aware that applying first aid to the burn-affected areas at home could result in a better outcome. The remaining 27% were uncertain, and 19% further believed that this practice would not lead to a better outcome. A local study that assessed the knowledge and awareness of first aid for burns among healthcare workers found that 90% of the participants understood that they could not touch a patient with a suspected electrical injury unless they were sure that the electricity source was turned off.10

Our study indicated a significant positive correlation between age and electrical burn-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as evidenced by a statistically significant increasing linear trend (P < .001). Conversely, no significant association was found between sex or nationality and electrical burn-related knowledge and attitudes (P > .05); however, these factors were significantly associated with electrical burn-related practices, wherein males demonstrated worse practices than females did (OR = 0.69, P < .001).

Our study also revealed a significant positive association between the education level and knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electrical burns. Specifically, compared with those with higher levels of education, respondents who had a high school level or lower level of education exhibited lower odds of possessing both a good knowledge (OR = 0.37, P < .001) and attitude (OR = 0.59, P < .001) and of engaging in good practices (OR = 0.53, P < .001) regarding electrical burns. Furthermore, compared with those who only completed university education, respondents who completed postgraduate education demonstrated a significantly higher odds of possessing good knowledge (OR = 1.79, P = .005) regarding electrical burns.

One study, which evaluated the level of understanding of electrical burn injuries in urban and rural communities, found that 35.6% of the urban population and only 12% of the rural population possessed particular knowledge about preventing electrical burn injuries. Furthermore, 69.4% and 88% of the urban and rural populations believed that sufficient information regarding electrical burn injuries was not readily available, respectively. Additionally, 61% and 96% of the urban and rural populations reported that they would have altered their behaviors in response to electrical burn injuries if they had access to more information, respectively.11

Our study demonstrated that a history of electrical injuries, whether experienced personally or within the family, was significantly associated with a lower odds of possessing good knowledge of (OR = 0.67, P < .001) and attitudes (OR = 0.79, P < .001) regarding electric burns.

An investigation into the impact of electrical burn prevention programs on occupational health hazard awareness among electrical workers revealed that the participants’ mean knowledge score (regarding first aid for electrical injuries) increased significantly from 1.44 ± 0.78 before the program to 6.44 ± 0.75 after the program. This improvement demonstrated noteworthy enhancement in the workers’ understanding of electrical injury prevention and management.12

Another study aimed at evaluating the level of knowledge regarding burn prevention among mothers of toddlers revealed that the mothers’ pretest and posttest knowledge scores (regarding electrical burns) were 1.35 and 2.33, respectively, with a significant difference between the two.13

The limitations of the study were the small number of participants, and we hoped to get more. Also, there was no previous questionnaire that we generated and we hope that it will be developed more with upcoming studies.

Enhancing community awareness and practices related to electrical burns is a cost-effective and straightforward strategy to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with electrical injuries.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, such results represent the fact that 27% and 19% did not know the correct answer and thought that this would not lead to a better outcome for applying first aid to the burn-affected areas at home; One-fourth of the respondents simultaneously plugged more than one appliance into a single outlet and one-third of the respondents reported using an indoor electric conductor in an outdoor yard make it essential for healthcare agencies to take the findings of this study seriously and address any shortcomings. Community incentives should be initiated with a focus on educating people about the importance of awareness and best practices for dealing with electrical burns. This education can be integrated into school and university curricula. In addition, community health campaigns should be launched at various locations, such as shopping centers and public gatherings, to demonstrate proper practices related to electrical burn injuries and raise awareness among different audiences.

Future planning and implementation of interventions focused on improving community awareness and practices regarding electrical burns. We hope that our findings will contribute to the existing body of knowledge on electrical burns and encourage further research in this area.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at the Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj, Saudi Arabia.

Contributor Information

Abdullh Z AlQhtani, Surgery Department, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj 11942, Saudi Arabia.

Nasser H Al-swedan, Surgery Department, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj 11942, Saudi Arabia.

Tala A Alkhunani, College of Medicine, King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh 11481, Saudi Arabia.

Abdulaziz A Basalem, Surgery Department, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj 11942, Saudi Arabia.

Abdulwhab M Alotaibi, Surgery Department, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj 11942, Saudi Arabia.

Khaled W Alsaygh, Surgery Department, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj 11942, Saudi Arabia.

Abdulrahman M AlSahabi, Plastic Surgery Department, Prince Sultan Military Medical City, Riyadh 11159, Saudi Arabia.

Abdulaziz O Alabdulkarim, Surgery Department, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj 11942, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions:

Abdullh AlQhtani (Conceptualization [lead], Data curation [lead], Formal analysis: [lead], Funding acquisition [lead], Investigation [lead], Methodology [lead], Project administration [lead], Supervision [lead], Validation [lead], Visualization [lead], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Nasser H. Al-swedan (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal]), Tala A. Alkhunani (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal]), Abdulaziz A. Basalem (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal]), Abdulwhab M. Alotaibi (Data curation [equal; Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal]), Khaled W. Alsaygh (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal]), Abdulrahman M. AlSahabi (Project administration [equal], Resources [equal], Supervision [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), and Abdulaziz O. Alabdulkarim (Conceptualization [equal], Project administration [equal], Resources [equal], Visualization [equal])

Funding:

No funding was received for this study.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional review board (IRB) of Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and Informed consent was taken by the participants.

Consent for publication:

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability:

The database set related to the manuscript submitted is available upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Forjuoh SN. Burns in low- and middle-income countries: a review of available literature on descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and prevention. Burns. 2006;32(5):529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peck MD, Kruger GE, van der Merwe AE, Godakumbura W, Ahuja RB.. Burns and fires from non-electric domestic appliances in low and middle income countries part I The scope of the problem. Burns. 2008;34(3):303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bounds EJ, Khan M, Kok SJ.. Electrical Burns. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee RC. Injury by electrical forces: pathophysiology, manifestations, and therapy. Curr Probl Surg. 1997;34(9):677–764. 10.1016/s0011-3840(97)80007-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haberal MA. An eleven-year survey of electrical burn injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995;16(1):43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brandão C, Vaz M, Brito IM, et al. . Electrical burns: a retrospective analysis over a 10-year period. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2017;30(4):268–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Najmi Y, Kumar P.. A retrospective analysis of electric burn patients admitted in King Fahad Central Hospital, Jizan, Saudi Arabia. Burns Open. 2019;3(2):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maghsoudi H, Adyani Y, Ahmadian N.. Electrical and lightning injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(2):255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghavami Y, Mobayen MR, Vaghardoost R.. Electrical burn injury: a five-year survey of 682 patients. Trauma Mon. 2014;19(4):e18748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mortada H, Malatani N, Aljaaly H.. Knowledge & awareness of burn first aid among health-care workers in Saudi Arabia: are health-care workers in need for an effective educational program? J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(8):4259–4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patil SB, Khare NA, Jaiswal S, Jain A, Chitranshi A, Math M.. Changing patterns in electrical burn injuries in a developing country: should prevention programs focus on the rural population? J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(6):931–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elsayed DM, Mekhmier HA.. Awareness of electricity workers regarding occupational health hazards: preventive study. Am J Nurs Res. 2017;5:219–225. 10.12691/ajnr-5-6-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sivaranjani, R. A Study to Assess the Effectiveness of Planned Health Teaching on Knowledge regarding Prevention of Burns in Toddler Children among Mothers in Medical Wards at Institute of Child Health and Hospital for Children, Egmore, Chennai - 08. Master’s thesis, College of Nursing, Madras Medical College; 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The database set related to the manuscript submitted is available upon request.