Abstract

Introduction

Benign lesions of the liver are very common findings, usually randomly discovered, especially during examinations for other indications. The frequent use of imaging modalities may be responsible for the statistical increase in the incidence of these findings.

Case Presentation

In this publication, we present the cases of 2 female patients with benign liver lesions, the occurrence of which is considered rare, and only a few dozen cases have been described worldwide. In both cases, clinical symptoms, diagnostic approach, and surgical treatment are presented.

Conclusion

Due to increasing availability of imaging methods, the occurrence of previously considered rare benign liver lesions increases as well. In many cases, the malignant potential of these findings remains unclear. Decision-making process should include a multidisciplinary board.

Keywords: Benign liver lesions, Hemangioma, Mucinous neoplasia

Introduction

Benign liver tumors are a very heterogeneous group of lesions with different germinal origins. They are mostly asymptomatic and discovered accidentally. The most common benign lesions include simple cysts, hemangiomas, focal nodular hyperplasia, and hepatocellular adenomas [1, 2]. The aim of this work was to point out rare focal lesions. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000536111).

Case Report No. 1

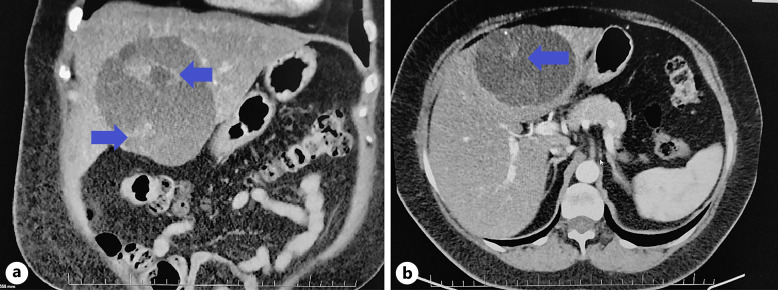

A 57-year-old female patient was referred for examination to the hepatopancreatobiliary surgery clinic of the University Hospital in Martin because of an incidental finding of liver cystic lesion during an ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen. In B-mode ultrasound imaging, the lesion had multichamber character with numerous septa without any nodules and reached approximately 110 × 60 mm in diameter. Subjectively, the patient felt well, she did not report any problems, she denied subfebrile and febrile, and her weight was stable. Subsequently, a computed tomography scan showed a multichamber complicated cyst of the liver with a size of 88 × 67 × 98 mm located at the boundary of the lobes predominantly on the left and a smaller multichamber cyst in the S6 segment with dimensions of 16 × 21 × 16 mm (Fig. 1a, b). In order to rule out a parasitic etiology, the patient underwent an examination by an infectiologist.

Fig. 1.

a, b Mucinous cystadenoma on contrast CT of the abdomen. On the left, a coronary section, on the right, an axial section in the left lobe of the liver, a visible hypodense lesion with an indicated heterogeneous nature of the content (archives of the University Hospital in Martin).

Due to the uncertain biological nature of the lesion, the patient was subsequently presented at a multidisciplinary seminar, where left hemihepatectomy by laparotomy was indicated. Multiple septation, thickened walls of the cyst, and internal nodularities are considered to be worrisome features associated with the risk of malignancy. According to the European Association of the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines, surgical resection is recommended as a gold standard for suspect mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver [1, 3]. During the revision of the abdominal cavity, an extensive cystic lesion affecting most of the left lobe of the liver and a smaller simplex cyst with a size of approximately 3–4 cm were visible in the S6 segment. A transection of the liver parenchyma was performed to the extent of the left hemihepatectomy.

Histological examination showed that they were cysts lined with single-layered cylindrical, in some places atrophied low epithelium with eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct diffuse intracytoplasmic mucous formation, while some of the cells showed the morphology of intestinal goblet cells. The wall of the cyst was formed by a ligament with the participation of spindle-shaped cells – immunophenotypically, it resembled the ovarian stroma. The finding was histologically concluded as cystic mucinous neoplasia of the liver – the so-called mucinous cystadenoma with low-grade dysplasias.

Case Report No. 2

At the beginning of June 2022, a 65-year-old female patient was hospitalized in the internal department for severe pancytopenia, about a month before arriving at the hepatopancreatic outpatient clinic of our clinic. On admission, the patient’s laboratory profile with corresponding reference values is listed in Table 1. Clinically, the patient reported weight loss with a gradual weight loss of 10 kg over the course of 6 months. In addition, the patient repeatedly vomited; she had been experiencing non-specific pain in the epigastrium and loss of appetite for a long time.

Table 1.

Laboratory profile of the patient with corresponding reference values

| Laboratory profile | Patient’s profile | Reference values |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 63 g/L | 120–160 g/L |

| Platelet count | 32 × 109/L blood | 150–400 × 109/L blood |

| Leukocyte count | 2.3 × 109/L blood | 4.0–10.0 × 109/L blood |

| Total proteins | 52 g/L | 66–83 g/L |

| Albumin | 36 g/L | 35–52 g/L |

| Total bilirubin | 29 µmol/L | 5–21 umol/L |

| AST | 2.2 ukat | <0.60 ukat |

| ALT | 0.9 ukat | <0.60 ukat |

| AFP | 6 kIU/L | <5.8 kIU/L |

| CA 19-9 | 39.7 kIU/L | <39 kIU/L |

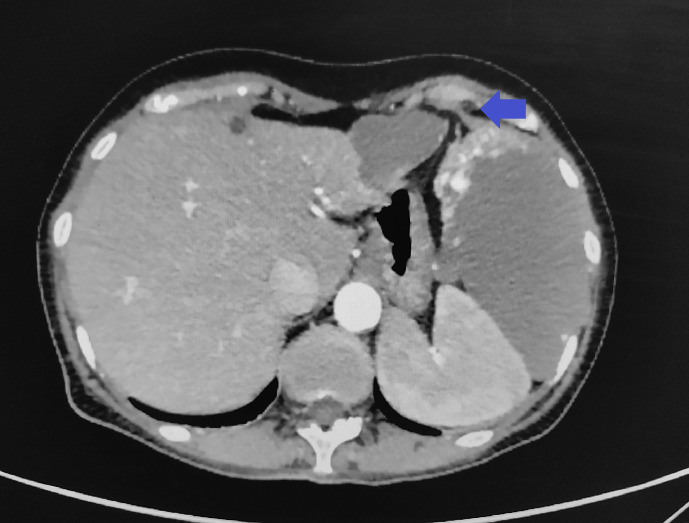

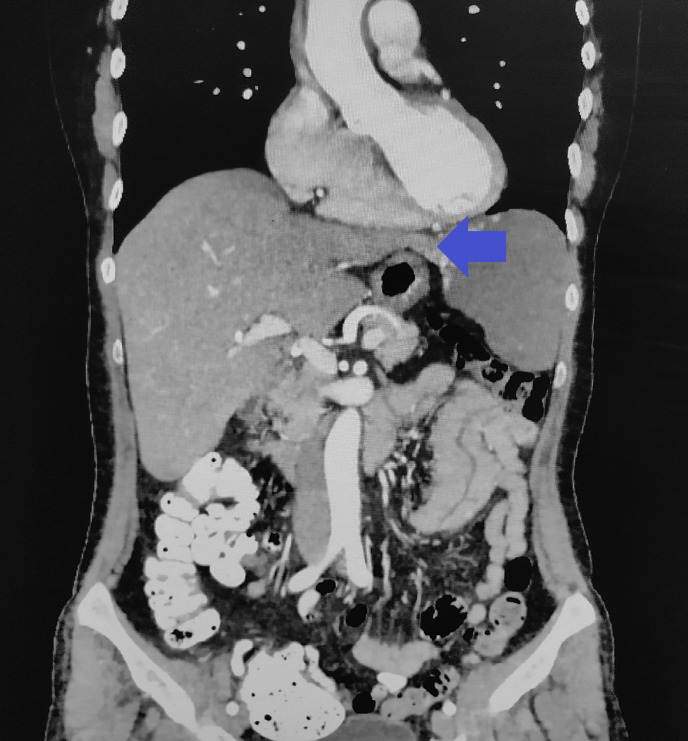

During hospitalization, an ultrasonography examination of the abdomen was performed, which revealed a lesion in the area of the spleen of unclear etiology. Subsequently, a CT scan of the abdomen was made and showed a liver lesion in the S2/S3 segment a peripheral lesion with a size of 43 × 30 mm, from which a lobular tumor extended into the left subphrenic with a size of 120 × 72 × 94 mm, compressing the spleen. Post-contrast, the lesion is nodularly filled at the periphery of the lesion, with gradual resaturation in the delayed phase – a hemangioma is considered in the differential diagnosis (Fig. 2, 3).

Fig. 2.

A pedunculated hemangioma on an axial CT section of the abdomen using a contrast material – clear compression of the spleen to the spine (archive of the University Hospital in Martin).

Fig. 3.

A pedunculated hemangioma on a CT coronal section abdomen with contrast material. Visible the pedunculus and typical nodular filling of the tumor periphery with contrast medium (archive of the University Hospital in Martin).

The patient underwent a hematological examination for the laboratory results, in which the condition is evaluated as macrocytic anemia, severe thrombocytopenia probably due to consumption coagulopathy thrombocytopenia due to giant liver hemangioma. During the hospitalization, the patient was given transfusions, which led to an improvement in the patient’s clinical condition. The patient was subsequently presented at a multidisciplinary seminar, on the basis of which a partial resection of the hemangioma in the S2/S3 segment of the liver together with its extrahepatic part was indicated. Performance of surgical resection of the lesion was proposed due to the risk of an acute torsion of the lesion and because of persistent anemia and thrombocytopenia. A left-sided bisegmentectomy of the liver was performed – left-sided lobectomy and resection of S2 and S3 segment laparotomies. The resection was subsequently sent for histological examination, which verifies a giant cavernous hemangioma. The postoperative course was without complications, and some laboratory parameters gradually improved – at discharge, the platelet count was 132 × 109/L of blood, the leukocyte count was 7.70 × 109/L of blood, hemoglobin 120 g/L. Approximately 2 months after discharge, patient underwent another hematological evaluation – laboratory parameters significantly improved compared to preoperative measurements. The diagnosis of the Kasabach-Merritt syndrome was confirmed.

Discussion

Benign focal lesions of the liver are an increasingly frequent finding, mainly due to the wide availability of imaging methods. In general, these lesions are divided into solid and cystic [4].

Cystic lesions of the liver represent a heterogeneous group of findings that differ from each other in prevalence, etiology, and clinical manifestation (Table 2). Mucinous cystic neoplasia in the liver is a very rare finding, which in the past was referred to as biliary cystadenomas or biliary cystadenocarcinomas. Today, they are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as epithelial neoplasia forming a cystic mass, mostly without communication with the biliary tract. The wall of this lesion is formed by cubic, cylindrical, in some cases mucin-producing epithelial cells, associated with a subepithelial stroma typical of the ovary. The presence of an ovarian stroma leads to the hypothesis of an embryonic origin. Several groups of authors assume that the proximity of the liver and gonads during embryonic development may result in the migration of gonadal cells to the surface of the liver and may thus lead to the formation of these lesions [5].

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of intrahepatic cysts (Soni et al. [5] 2021)

| Simple cyst | Polycystic disease | Parasitic | Neoplastic | Duct related | False cyst |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echinococcal | Primary: cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma | Caroli’s disease | Traumatic intrahepatic hemorrhage | ||

| Secondary: carcinoma of ovary, pancreas, kidney, colon, neuroendocrine | Bile duct duplication | Intrahepatic infarction | |||

| Intrahepatic biloma |

In terms of prevalence, mucinous cystadenoma accounts for approximately 5% of all cystic lesions of the liver in adults. This slow-growing tumor occurs predominantly in middle-aged women, which also correlates with the case of our patient. Despite the fact that it is generally considered a benign lesion, its malignant transformation can rarely occur during life [6]. In up to 75% of cases documented so far, mucinous cystadenoma occurs in the left lobe of the liver [7].

Clinically, the tumor can be completely asymptomatic or manifested by non-specific abdominal pain or abdominal discomfort, nausea, or vomiting; therefore, it is often an incidental finding when performing imaging examinations for other indications. Obstructive icterus due to compression of the biliary tract, cholangitis, bleeding into the cyst, or rupture of the cyst can be potential complications [8].

On ultrasonography of the abdomen, mucinous cystadenoma typically appears as a hypoechoic lesion with thickened irregular walls, inside which there are distinct nodularity and debris [1]. Despite the fact that USG of the liver is the first-line imaging modality, it cannot be used to reliably demonstrate whether it is a neoplastic cyst or not.

On a CT scan of the abdomen with the use of a contrast agent, mucinous cystadenoma appears as a hypodense lesion with internal septations highlighted by the contrast agent, sharply demarcated from the surroundings [8]. The hemorrhagic nature of the cyst contents, an intramural nodule, or calcification along the wall or septum may suggest malignancy, but, as with USG, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma cannot be reliably differentiated by imaging methods [9].

According to the European Association of the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines, performance of CEUS or contrast-enhanced CT/MR is recommended in cases when the liver lesion has an atypical appearance on B-mode ultrasonography, or when the lesion occurs in patients with underlying liver disease or in patients previously diagnosed with cancer [10]. Despite that, World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology guidelines recommend CEUS as a first-line imaging modality in patients with focal liver lesion at ultrasound without underlying liver cirrhosis or history/suspicion of malignancy [11]. CEUS as a imaging method reveals vascularization of septa and nodules with high sensitivity. Because of that, diagnoses such as echinococcosis or simple cyst of the liver can be excluded [12].

The effectiveness of preoperative morphological diagnosis is considerably limited, including fine-needle biopsy and core-cut biopsy. In the material taken by fine-needle biopsy, clusters of cubic or cylindrical cells are formed against a watery or mucinous background. However, a core-cut biopsy is not recommended due to the cystic nature of the lesion, as it is not possible to obtain a representative sample. Since a reliable differentiation between cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma is not possible on the basis of imaging examinations, biopsy poses the risk of potential peritoneal dissemination; therefore, its implementation is not recommended preoperatively [9].

As for hemangiomas, they represent the most common benign mesenchymal tumor of the liver, with a prevalence of 0.4–20%. Based on current knowledge, hemangiomas have probably no malignant potential [13]. Most often they occur solitary, but multiple lesions can also occur, and they are categorized according to size – we refer to hemangiomas with dimensions between 1 cm and 2 cm as small, and if their size exceeds 10 cm, we refer to them as huge [14]. We distinguish several variants, and one of the rarest forms is the so-called pedunculated hemangioma, which represents an exophytically growing lesion, most often emerging from the left lobe of the liver. According to Al Farai A., only 24 cases [15] have been described worldwide. Pedunculated hemangiomas can be asymptomatic, but due to their size and extrahepatic localization, they can compress the bile ducts, surrounding abdominal organs or vascular structures. However, its presence can also lead to some serious conditions, such as its spontaneous or traumatic rupture, bleeding into the tumor/into the peritoneal cavity, and possibly thrombosis, hyalinization, or progressive fibrosis [16].

The diagnosis of a pedunculated hemangioma can be quite difficult, as the peduncle may not be visualized by imaging methods. The most frequently used modalities are ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance. On CT with the use of a contrast agent, hemangioma typically presents with nodular saturation of the periphery in the early phase and subsequent centripetal saturation, which persists until the late phase [17]. In the case of our patient, ultrasonography, CT, and MR of the abdomen were performed, while the pedicle of the hemangioma was well visualized on the CT, and in the early phase there was a characteristic nodular filling of the lesion on the periphery, which persisted until the late phase. A serious complication of this form is torsion of the pedicle with its subsequent infarction, especially in cases where the pedicle is long and the tumor is mobile [16].

Above all, large hemangiomas can be clinically manifested by abdominal pain in the epigastrium, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, the presence of palpable resistance, or hemorrhage [17]. Another potential manifestation is the so-called Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, which presents with hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, or prolonged prothrombin time (PT). Most often, this syndrome manifests itself in childhood, it is very rare in adults, but there have been documented cases when it was accompanied by the presence of a giant hemangioma [18]. The pathogenesis of Kasabach-Merritt syndrome most likely involves both primary and secondary hemostatic mechanisms, leading to platelet clumping, activation, and aggregation and thus to their consumption, along with activation of the coagulation cascade within the abnormal vascular structure of the hemangioma [19].

Clinically, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome can be associated with abdominal pain or abdominal discomfort, especially in the case of a rapidly growing tumor, which was also the case with our patient. The laboratory profile is characterized by significant thrombocytopenia, typically in the range from 3,000 to 60,000 platelets per microliter, with the possibility of manifestation in the form of surface petechiae. PT and activated partial PT are in most cases within the range of reference values, the level of fibrinogen is reduced, and conversely, the level of fibrin degradation products is elevated. Anemia may also appear as a result of bleeding into the lesion, coagulopathy, and eventual sequestration of blood into the tumor [20]. The definitive solution is surgical removal.

Conclusion

The increasing incidence of focal liver lesions is mainly due to the wide availability of imaging examinations, mainly transabdominal ultrasonography and CT examination. The evaluation of their malignant potential remains a problem in clinical practice, especially in patients with a history of oncological disease. The basis is a multidisciplinary approach.

Acknowledgments

This publication has been produced with the support of the Integrated Infrastructure Operational Program for the project: research and development of a telemedicine system to support the monitoring of a possible spread of COVID-19 in order to develop analytical tools used to reduce the risk of infection, ITMS: 313011ASX4, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from both patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images at Internal Gastroenterological Department of University Hospital in Martin during hospitalization of both patients. Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guideline.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Nosáková Lenka, Pindura Miroslav, Vojtko Martin, Cmarková Kristína, Miklušica Juraj, and Bánovčin Peter have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This article was not supported by any funding.

Author Contributions

Lenka Nosáková, Kristína Cmarková, Martin Vojtko, and Miroslav Pindura had substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. Peter Bánovčin revised it critically for important intellectual content, and Juraj Miklušica gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding Statement

This article was not supported by any funding.

Data Availability Statement

All used data are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL . EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol. 2016;65(2):386–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marrero JA, Ahn J, Rajender Reddy K, Americal College of Gastroenterology . ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1328–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joost D, Thijs B, Hermien H, Frederik N, Richard T, Roser TB, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of cystic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2022;4(77):1083–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rave SD, Hussain SM. A liver tumour as an incidental finding: differential diagnosis and treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(236):81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Soni S, Pareek P, Narayan S, Varshney V. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver (MCN-L): a rare presentation and review of the literature. Med Pharm Rep. 2021;94(3):366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferraguti DA, McGetrick M, Zendejas I, Hernandez-Gonzalo D, Gonzalez-Peralta R. Mucinous cystadenoma: a rare hepatic tumor in a child. Front Pediatr. 2017;5(1):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yeh J, Palamuthusingam P. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2020:2020(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferreira R, Abreu P, Jeismann VB, Segatelli V, Coelho FF, David AI. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver with biliary communication: case report and surgical therapeutic option. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mezale D, Strumfa I, Vanags A. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver and extrahepatic biliary tract, topics in the surgery of the biliary tree. London, (UK): IntechOpen: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL; Forner A, Ijzermans J, Paradis V, Reeves H, Vilgrain V. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol. 2016;65(2):386–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson SR, Feinstein SB. Introduction: 4th guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver-update 2020 WFUMB in cooperation with EFSUMB, AFSUMB, AIUM and FLAUS. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(12):3483–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dong Y, Wang WP, Zadeh ES, Möller K, GörgBerzigotti CA, Chaubal N, et al. Comments and illustrations of the WFUMB CEUS liver guidelines: rare benign focal liver lesion, part I. Med Ultrason. 2023;1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Ye Z, Tan L, Luo J. Giant hepatic hemangioma regressed significantly without surgical management: a case report and literature review. Front Med. 2021;8(8):712324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evans J, Willyard CE, Sabih DE. Cavernous hepatic hemangiomas. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470283/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castañeda Puicón L, Trujillo Loli Y, Campos Medina S. Torsion of a giant pedunculated liver hemangioma: case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;75(2020):207–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al Farai A, Mescam L, De Luca V, Monneur A, Perrot D, Guiramand J, et al. Giant pedunculated hepatic hemangioma: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11(2):476–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang X, Zhou Z. Hepatic hemangioma masquerading as a tumor originating from the stomach. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1406–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu X, Yang Z, Tan H, Xu L, Sun Y, Si SJ, et al. Giant liver hemangioma with adult Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: case report and literature review. Medicine. 2017;96(31):e7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masters S, Kallam D, Eo H, Peddi P, Adams DM, Garzon MC. Clinical review: management of adult kasabach-merritt syndrome associated with hemangiomas. J Blood Disord Transfus. 2017;8(5). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahajan P, Margolin J, Iacobas I. Kasabach-merritt phenomenon: classic presentation and management options. Clin Med Insights Blood Disord. 2017;10(16):1179545X17699849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All used data are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.