Abstract

Advancements in systemic therapies for patients with metastatic cancer have improved overall survival and, hence, the number of patients living with spinal metastases. As a result, the need for more versatile and personalized treatments for spinal metastases to optimize long-term pain and local control has become increasingly important. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has been developed to meet this need by providing precise and conformal delivery of ablative high-dose-per-fraction radiation in few fractions while minimizing risk of toxicity. Additionally, advances in minimally invasive surgical techniques have also greatly improved care for patients with epidural disease and/or unstable spines, which may then be combined with SBRT for durable local control. In this review, we highlight the indications and controversies of SBRT along with new surgical techniques for the treatment of spinal metastases.

Keywords: dose selection, local control, SBRT, spinal metastases, target delineation

Key Points.

Management of spinal metastases has been revolutionized over the last decade due to advances in stereotactic body radiation therapy and increasing utilization of minimally invasive surgical techniques.

The incorporation of serum biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA into standard practice may ultimately play an important role in both optimization of treatment paradigms and response assessment.

The importance of this manuscript is to review recent data and future directions in the rapidly evolving and increasingly utilized field of spine SBRT.

Only a few decades ago, metastatic disease was associated with limited survival and management decisions were with purely palliative intent. In 2005, a landmark prospective randomized trial by Patchell et al.1 demonstrated that surgery for decompression in combination with postoperative conventional external beam radiation therapy (cEBRT) was associated with significantly superior rates of preservation of ambulation than cEBRT alone in patients with malignant spinal cord compression due to solid tumors. This study served as the foundation for the treatment paradigm of pairing decompressive surgery with radiation therapy in patients with spinal metastases.

Due to the advancements in systemic therapies to improve disease control as well as imaging for disease surveillance, survivorship with metastatic cancer is improving. Approximately 30%–70% of oligometastatic patients will develop disease to the spine, with about 10% becoming symptomatic from spinal cord compression.2 Therefore, less invasive, more personalized, and versatile treatments for local control of spinal metastases are needed. Personalization applies to a multimodal interdisciplinary approach with the incorporation of separation surgery for high-grade epidural disease, cement augmentation procedures, and percutaneous ablative procedures such as radiofrequency ablation and photodynamic therapy followed by postoperative (or even preoperative) spine stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).3,4

Stereotactic body radiation therapy offers precise delivery of ablative, high-dose-per-fraction conformal radiation in fewer fractions while limiting the dose to adjacent critical structures like the spinal cord.5 The term “fraction” is synonymous with treatment. The treatment total dose is the amount of radiation delivered per treatment times the number of fractions. The decision framework for spinal metastasis treatment incorporating neurologic, oncologic, mechanical instability, and systemic disease (NOMS) assessments has improved the timing and success of postoperative SBRT.3 Initial spine SBRT practice was modeled after intracranial stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) resulting in single-fraction regimens ranging from 16 to 20 Gy, with escalation to 24 Gy in selected institutions, with the intent to optimize local control.6 Though high-dose single-fraction spine SBRT is efficacious with local control, there is still significant concern for toxicities such as myelopathy and vertebral compression fracture (VCF).7 The purpose of this review is to highlight the indications and controversies of SBRT along with new surgical techniques for the treatment of spinal metastases.

NOMS Decision Framework

The NOMS paradigm, first developed at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, has served as the decision framework for guiding treatment of spinal metastases (Table 1).3 The neurologic assessment considers mainly the degree of epidural spinal cord compression (ESCC), along with the presence of myelopathy or functional radiculopathy. The degree of ESCC is graded by a 6-point system designed and validated by the Spine Oncology Study Group (SOSG) using axial T2-weighted MRI images.8 Patients with high-grade ESCC (grade 2 or 3) are recommended for surgical decompression unless the tumor is highly radiosensitive. Those with lower-grade ESCC (grade 0, 1a, or 1b) and without mechanical instability are recommended for radiation treatment upfront, while the initial treatment type for patients with grade 1c is not clearly defined.

Table 1.

NOMS Decision Framework

| Neurologic | Clinical: presence of myelopathy or functional radiculopathy |

Radiographic: scoring system for Epidural Spinal Cord Compression8

| |

| Oncologic | Radiosensitive

|

Radioresistant

| |

| Mechanical instability | Spine Oncology Study Group Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score9

|

| Systemic disease | Systemic comorbidities and tumor burden

|

The oncologic assessment considers the radiation sensitivity of a tumor type to cEBRT. Highly radiosensitive histologies include lymphoma, germ cell tumors, myeloma, and small cell lung cancer, as well as moderately radiosensitive breast, prostate, ovarian, and neuroendocrine carcinomas, which are treated initially with cEBRT.10–12 Radioresistant tumors include renal, thyroid, hepatocellular, colon, non–small cell lung carcinomas, sarcoma, and melanoma, which may benefit from dose escalation with SBRT.10–12 This change was a significant improvement for patients with radioresistant tumors, who were previously referred for surgery due to poor local control by cEBRT. However, there are still modest results of SBRT in patients with metastatic sarcomas.13 Patients with radioresistant or previously radiated tumors with high-grade ESCC require surgical decompression prior to radiation treatment.3 Ultimately, patients with a neurologic decline due to pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots from high-grade ESCC shift the decision framework toward urgent surgery for decompression regardless of whether the histology is radiosensitive, radioresistant, or unknown.

Mechanical instability is a separate assessment regardless of the degree of ESCC or tumor histology. The assessment of instability is made using clinical and radiographic criteria with the Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score (SINS), which was developed by Spine Oncology Study Group.9 The grading is based upon location, pain, alignment, osteolysis, vertebral body collapse, and posterior element involvement. A higher score necessitates stabilization via either surgery or percutaneous cement augmentation. Stabilization of the spine may affect timing of SBRT as the priority in management is to treat an instability of the spine prior to initiating radiation treatment.

Whether a patient can tolerate a surgery or procedure is based upon the systemic assessment, which considers the extent of a patient’s tumor burden and histology as well as comorbidities. Patients with significant comorbidities resulting in poor underlying health or aggressive, disseminated tumors do not benefit from surgical procedures requiring long hospitalizations and recovery. Multiple scoring nomograms are available for prognosticating survival in patients with metastatic disease.14 However, with new advances in minimally invasive surgical techniques, more patients can tolerate a procedure and are considered on an individual basis after discussion with an oncologist rather than using a prediction model. In patients who cannot tolerate a procedure, radiation is the only targeted treatment option available. An example of a case of mechanical instability and treatment is provided in Figure 1.

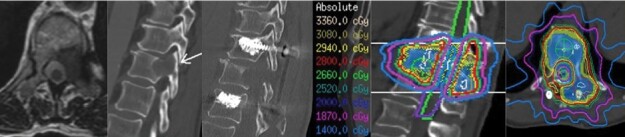

Figure 1.

Patient with oligometastatic esophageal cancer presenting with a T11 metastasis and Bilsky 1A and lytic disease involving the vertebral body and ipsilateral pedicle with a pathologic fracture. The patient had mechanical and radicular pain and a Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score of 12. They also had radicular pain. The patient underwent T10–T12 instrumentation with a T11 left-sided transpedicular decompression and resection of tumor. The patient’s mechanical pain and radicular pain resolved after surgery and they underwent simulation 5 days later for postoperative stereotactic body radiation therapy with 28 Gy in 2 fractions.

Advances in Surgical Interventions and Implants

The treatment pendulum for spinal metastasis has shifted from more invasive surgeries for large resections followed by low-dose radiation treatment to less invasive separation surgeries as a neoadjuvant to radiation treatment for tumor control.15,16 A separation surgery consists of resecting predominantly the epidural disease in patients with ESCC to create a 2–3 mm separation between the tumor and the spinal cord without having to remove tumor in the vertebral body or in the paraspinal extension followed by SBRT (Figure 2).17

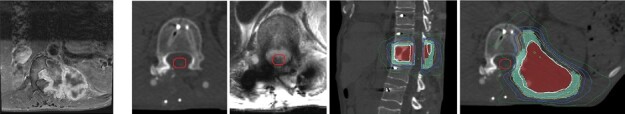

Figure 2.

Patient with metastatic epithelioid sarcoma to T12 who underwent separation surgery with T10-L2 fusion using carbon fiber-reinforced polyetheretherketone instrumentation. Postoperative MRI and CT show minimal artifact for SRS planning.

Advancements in intraoperative navigation, including robotics and augmented reality, have the potential to improve spine fixation and tumor resection.18 One study completed in 70 patients with metastatic spine disease showed that robot-assisted placement of pedicle screws was just as effective and safe as conventional placement.19 Additionally, the use of augmented reality increases ease of pedicle screw placement while also providing a 3D overlay of the tumor on the patient’s anatomy with navigated instruments to help with precise cuts for tumor resection.20–22 The increased efficiency also reduces the time of surgery.23 These new technologies provide increased precision, which allows for less tissue disruption, more accurate fixation, and improved tumor resection and postoperative epidural disease burden, which is predictive for local control. Given the less invasive approach, patients can start SBRT promptly, often 2 weeks after surgery.

The carbon fiber-reinforced polyetheretherketone (CF/PEEK) screw and rod-based systems reduce imaging artifact on MRI and CT compared to titanium hardware, may help to improve cancer surveillance (Figure 2).24 In addition, it may reduce the need for CT myelogram for target contouring for postoperative SBRT when MRI distortion is significant. There is also a reduction in radiation dose perturbation, particularly with proton therapy,25,26 and potential for improved dose calculations.27,28 Emerging data suggests that CF/PEEK hardware has similar safety profiles and biomechanical properties including screw loosening, stiffness, cycling capacity, and bending.29–31

Concerns with CF-PEEK instrumentation include the high cost, lack of a posterior cervical fixation system, and more limited ability to contour the rods.32 Hybrid constructs of CF/PEEK with titanium screws outside the radiation therapy field have helped to reduce costs, as well as the use of bendable titanium rods to correct associated deformity. Khan et al. reported the incidence of implant-related complications and reoperation with CF/PEEK to be slightly higher compared to titanium (7.8% vs 4.7% and 5.7% vs 4.8%, respectively).33 In that series, local recurrence rates were slightly higher with CF/PEEK versus titanium (14.4% over a 10.7-month mean follow-up and 10.7% over 20.2-month mean follow-up, respectively).33 Further data focused on long-term outcomes on patient outcomes, implant failure rates, complications, and fusion rates are needed before firm conclusions can be made to justify routine adoption of this costly system.

Dose Selection and Factors That Impact Local Control

As patients with spine metastases are still palliative and pain control is the predominant objective of radiation, the ability of spine SBRT to achieve superior symptom control compared to cEBRT has been debated. Nonetheless, there are now 3 randomized clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of spine SBRT for pain control to cEBRT. The Sprave et al. phase II clinical trial randomized 55 patients to single-fraction spine SBRT (24 Gy) versus cEBRT (30 Gy in 10 fractions).34 Though the primary outcome of pain response (>2 point improvement on the visual analog scale) at 3 months suggested a trend for superiority (70% SBRT vs 48% cEBRT, P = .13), the difference became statistically significant at 6 months (74% SBRT vs 35% cEBRT, P = .02). Importantly, when comparing complete response (CR) rates, at 3 and 6 months, the CR rates following SBRT versus cEBRT were 43.5% versus 17.4% (P = .057) and 52.6% versus 10% (P = .003), respectively, and a faster time to pain response with SBRT was observed (P < .001). Toxicity rates were similar with the exception of new VCF, which was 9% for SBRT versus 4% for cEBRT at 3 months, and 28% for SBRT versus 5% for cEBRT at 6 months.35 This trial was not powered beyond a sample size of convenience and phase III trials were needed to confirm these observations.

The Canadian Clinical Trials Group (CCTG) along with the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG), led the phase 2/3 randomized trial (SC.24), which was the first fully reported phase III trial investigating spine SBRT for pain control.36 In this trial, spine SBRT (24 Gy in 2 fractions) was compared to cEBRT (20 Gy in 5 fractions) in 229 patients with intact, not previously irradiated, spine metastases with a baseline pain score of at least 2.36 In the initial publication by Sahgal et al., significantly higher CR rates for pain were seen with SBRT compared to cEBRT at 3 months (35% vs 14%, P < .001), achieving the primary endpoint. The superiority in CR rate for SBRT was also maintained at the 6-month postradiation timepoint (32% vs 16%, P = .004).36 Importantly, the patient population for SC.24 consisted of mainly high-functioning (ECOG 0 or 1) patients with no obvious spinal instability (SINS <13), neurological compromise, or highly radiosensitive primary histology (seminoma, small cell lung cancer, or hematological malignancies). Fracture rates were similar in both arms at ~10%, which was consistent with prior nonrandomized outcomes with the 2-fraction SBRT regimen. Therefore, together with the Sprave et al. trial, the results of spine SBRT for pain control are consistent and supportive of a recommendation for spine SBRT in patients with painful spinal metastases with a survival of at least 3 months that meet the inclusion criteria. A subset analysis with mature outcomes also supported improved local control and lower retreatment rates with SBRT.37

However, the recently reported RTOG 0631 phase III trial by Ryu et al. showed no differences between single-fraction SBRT (16 or 18 Gy) versus cEBRT (8 Gy in 1 fraction) with respect to pain control or local control.38 The proportion of patients with a ≥3 point decrease in the Numerical Rating Pain Scale was 41% following 16 or 18 Gy in 1 fraction and 61% following 8 Gy in 1 fraction at 3 months (1-sided P = .99 and 2-sided P = .01 in favor of 8 Gy in 1 cEBRT fraction).39 Pain response was not significantly different at 6 months. Additionally, local control was not significantly different between 16 or 18 Gy in 1 SBRT fraction versus 8 Gy in 1 cEBRT fraction (66% vs 58%, respectively). There were many methodological differences between this study and the previously summarized trials and it is notable that both Sprave et al. and Sahgal et al. standardized the definition of pain response according to International Consensus Pain Response Endpoints.40,41 Selected sentinel prospective studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sentinel Prospective Studies

| Study | Study type | N | Radiation | CTV volume | Pain control | Local control at treated site | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sahgal et al.36 | Randomized, controlled, phase II/III trial (Intact Denovo SBRT) |

229 |

SBRT 24 Gy in 2 fx vs cEBRT 20 Gy in 5 fx in 1:1 ratio | Per consensus contouring guidelines | At 3 months: SBRT arm pain CR 35%, PR 18%, stable pain 24%, progressive pain 6%; cEBRT arm: CR 14%, PR 25%, stable pain 30%, progressive pain 12% (P = .0002) | 86% (95% CI 78–91) in cEBRT arm and 92% (85–96) in SBRT arm at 3 months (P = .18), and 69% (60–77) in cEBRT arm and 75% (65–82) in SBRT arm at 6 months (P = .34) | Pain flare in 4% of cEBRT arm vs five 5% of 110 patients in the SBRT arm. VCF in 17% of cEBRT arm and 11% of SBRT arm. 94% of VCFs were grade 1. Grade 4 VCF in 1% of each arm |

| Ryu et al.38 | Randomized phase III trial (Intact Denovo SBRT) | 339 | SBRT 16 Gy/18 Gy in 1 fx vs cEBRT 8Gy in 1 fx in 2:1 ratio | Gross disease, involved body and both left and right pedicles | Three-point improvement in numerical pain radiation scale at 3 months in SBRT arm 41.3% and cEBRT arm 60.5% (P = .01) | Progression of known metastases 34% in SBRT arm and 42.3% in cEBRT (P = 12) | Acute any grade AEs at 3 months 7.7% in both arms. Late AEs 5.6% SBRT and 3.4% cEBRT arm (P = .38). VCF at 24 months 19.5% SBRT and 21.6% cEBRT |

| Sprave et al.34 | Randomized phase II (Intact Denovo SBRT) | 55 | SBRT 24 Gy in 1 fx vs cEBRT 30 Gy in 10 fx in 1:1 ratio | Gross disease, involved vertebral sector and any uninvolved vertebral sector | Faster decrease in pain within 3 months in SBRT arm (P = .01). At 6 months, lower pain scores in the SBRT group (P = .002). Improved pain response in SBRT arm at 6 months (P = .003) | NR | No ≥ grade 3 acute or late AEs. No radiation myelopathy or cauda equina injury |

| Ito et al.42 | Single arm phase II (Post-Op SBRT) | 33 | SBRT 24 Gy in 2 fx | Per consensus contouring guidelines | Pain response rates (CR or PR) at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months were 82% (18 of 22 patients), 92% (22 of 24 patients), 80% (16 of 20 patients), 74% (14 of 19 patients), and 83% (15 of 18 patients), respectively | 87% at 12 months | No radiation myelopathy. Radiculopathy in 1 patient following local recurrence and reirradiation. VCF in 6 patients. |

| Redmond et al.43 | Single arm phase II (Post Op SBRT) | 35 | SBRT 30 Gy in 5 fx | Per consensus contouring guidelines | Reduction in pain in treated area 54.2%, stable 12.5%, increased by 1 point in 8.3%, and increased by ≥2 points in 25%; 20.8% no pain in any part of body at last recorded follow up | 90% at 12 months | No ≥ grade 3 acute or late AEs. No radiation myelopathy or cauda equina injury |

| Wang et al.44 | Phase 1, 2 (Intact Denovo SBRT) | 149 | 27–30 Gy in 3 fx | Gross disease plus surrounding vertebral body and additional structures deemed to be at risk | Significant increase in patients with no pain between baseline and 4 week, 3 months and 6 months (26 to 39%, P = .038; 26 to 44%, P = .004; 26 to 54%, P < .0001 respectively). Significant decrease in percentage of patients with moderate-to-severe pain (rated ≥5 on the 0–10 scale) noted from baseline to 4 weeks (P = .003), 2 months (P < .0001), and 6 months (P = .002). | 72% local control with failure occurring at a median of 13 months (range: <1–101 months) | Grade 3 toxicity included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, non-cardiac chest pain, dysphagia, neck pain, diaphoresis, and pain associated with severe tongue edema and trismus. No grade 4 toxicity and no radiation myelopathy |

Abbreviations: AE: adverse events; CR: complete response; cEBRT: conventional palliative radiotherapy; fx: fractions; SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy; VCF: vertebral compression fracture.

In general, oncologic care is increasingly adopting personalized approaches to the patient, and this also includes spine SBRT dose selection. For example, we have learned the importance of the primary histology in determining dose. More specifically, radioresistant histologies have been associated with significantly higher risks of local recurrence despite the high-dose approach inherent to spine SBRT. As compared to prostate cancer primaries as a radiosensitive comparator, failure rates in those radioresistant tumors were 22.4% versus 8.4% at 2 years, P < .001, respectively.45 Furthermore, even within the prostate cancer cohort, 2-year local control rates were worse for those with castrate resistance versus castrate sensitive (78% vs 95%, respectively). These data support the potential role of dose escalation in selected patients, and greater global experience and well-controlled trials are needed to determine optimal spine SBRT dosing. For other primary sites where molecular diagnostics are increasingly adopted into staging and clinical decision-making (eg, HER2 status for breast cancer, EGFR/ALK/ROS/PD-L1 for lung cancer, BRAF for melanoma, and so on), additional data are needed to determine the role of spine SBRT dose escalation or de-escalation, similar to what has been suggested in the management of brain metastases with radiosurgery.46

There are also anatomic considerations that can personalize spine SBRT with several analyses identifying the presence of epidural and/or paraspinal disease extension as independent risk factors for local failure.37,47 For example, an approach of selective dose escalation to the paraspinal disease component may develop as a simultaneous integrated boost. In addition, cautious relaxation of the critical neural structure dose constraints in those tumors with high-grade epidural disease may be warranted to improve disease control.

Normal Tissue Constraints and Toxicity

Although local control with SBRT is excellent, ablation of a tumor near critical structures is not without toxicity. Specifically, high-dose spine SBRT can be associated with myelopathy, nerve root and plexus injury, and vertebral body compression fracture. To mitigate the toxicity, some institutions have adopted the use of multifraction regimens. The rationale is that regimens ranging from 2 to 5 fractions allow greater recovery of normal tissues between fractions, closing the ratio between tumoricidal doses and normal tissue constraints.48 When planning spine SBRT, strict dose constraints need to be observed to the critical adjacent organs-at-risk, as treatment with high doses per fraction results in a greater risk of both acute and late toxicity than would otherwise be expected with cEBRT. This results in an “isotoxic” approach to planning and treatment plan evaluation such that coverage of the target volume is secondary to safety, and although across the field of radiation oncology, it is physicians expect at least 95% coverage of the planning target volume by the 95% prescription isodose line, it is not unusual to achieve 80%–90% planning target volume coverage in spine SBRT depending on the clinical and anatomic characteristics of the case. Ultimately, safety of the spinal cord needs to be the first priority.

More specifically, spinal cord dose constraints have been intensively studied due to the catastrophic nature of myelopathy and the sensitivity of dose exposure to small volumes given the predominantly serial nature of the tissue, meaning that toxicity may be driven by maximum doses to small volumes.49 Fortunately, radiation myelopathy following spine SBRT is a rare event given the reported evidence-based spinal cord constraints and the more cautious approach of adopting safety margins as a standard spine SBRT procedure.49 Over time, the constraints have been relaxed as the global experience has grown, and improvements in both technology and imaging have been realized allowing more precise patient setup and treatment delivery. Most recently, the HyTEC initiative performed extensive modeling providing a low and high-dose threshold while still respecting a 1%–5% risk of myelopathy.50 However, there remains a significant need to better define dose constraints of other dose-limiting OAR such as nerve roots, nerve plexi, and esophagus since, at present, the primary dose constraints that are utilized for spine SBRT are derived from other treatment scenarios. In addition, guidance with respect to the need to modify these constraints in patients being treated with targeted or immune checkpoint therapies is needed although preliminary data does suggest that combining immunotherapy and spine SBRT is safe.51,52 However, an association with high-grade esophageal adverse events and systemic therapies associated with radiation recall phenomena was reported by Cox et al.,53 in addition to iatrogenic manipulation of the esophagus soon after SBRT.

As experience with spine SBRT grew, the effects of high-dose radiation on bone tissue were observed manifesting as VCF. The incidence of posttreatment VCF has been reported to be as high as 39% with a high-dose single fraction (≥24 Gy).54,55 The time between SBRT and VCF is variable among studies but ranges from 2.5 to 25 months with the highest risk in the first 3 months.56 A primary driver of the risk is the radiation dose per fraction with many studies showing risks of approximately 10%.57 However, a recent normal tissue complication probability analysis suggests that the low-dose bath to the vertebrae may contribute to the risk of VCF as well.58

A dose-complication relationship was observed such that a reduction in the dose per fraction (24 vs 20–23 Gy vs ≤19 Gy per fraction) was associated independently with a lower risk of VCF.54 However, spine SBRT represents a delicate balance between tumor and normal tissue response, and there is a randomized trial, which suggests 24 Gy in a single SBRT fraction may yield superior local control as compared to 24–27 Gy in 3 SBRT fractions, which requires confirmation.59 Therefore, as the dose per fraction is reduced to take advantage of a protective effect on the bone tissue, an escalation of the total dose is recommended to maintain local control. Fortunately, a recent report from the HyTEC initiative has established iso-effective doses at multiple fractionations for tumor control. To achieve a 90% tumor control probability, it is recommended to treat with 20 Gy in 1 fraction, 28 Gy in 2 fractions, 33 Gy in 3 fractions, 36 Gy in 4 fractions, or 40 Gy in 5 fractions.60 Recently, a comparison of outcomes following 24 versus 28 Gy, both delivered in 2 fractions, provided a degree of validation for the model, with superior local control following 28 Gy.47 Importantly, in that study, the risk of VCF was similar between the cohorts as the dose per fraction was still under 19 Gy.

While there are studies currently underway administering a more protracted fractionation and assessing for a reduction in VCF risk, no current randomized trials investigating SBRT regimens effect on bone health are underway. An in vivo animal model was developed to analyze the effects of focal radiation on bony microstructure.61 Doses were given in either 24 Gy single dose or 8 Gy in 3 fractions and lumbar vertebrae were studied 6 months after irradiation. The single-dose treatment was associated with decreased vertebral bone volume and trabecular number as well as lower fraction loads and stiffness, whereas the hypofractionated dose preserved bone volume and maintained a similar fracture load and stiffness compared to controls. Furthermore, osteogenic features were persevered in the hypofractionated group. Therefore, a single dose was more detrimental to bone health than the hypofractionated regimen.

Of note, the rate of incidental VCF in metastatic spine disease ranges from 8% to 24% depending on the tumor type.62 Due to the high percentage of incidentally found VCFs, one area for debate has been whether there is an increased risk of developing fractures due to SBRT alone or if the spine would have developed a fracture regardless due to loss of bony integrity from an infiltrative lytic lesion. Other risk factors include the presence of lytic disease, prior VCF, deformity, increased age, >40%–50% of the vertebral body infiltrated by tumor, and high SINS score (indicating instability).56,63 Gui et al. reported on a machine learning paradigm to predict VCF within 1 year after SBRT based upon clinical characteristics and radiomic features such as patient BMI and performance status, total prescription dose, location of treatment, and SINS lytic tumor component, and spinal misalignment.64 If patients meet the risk factors, they should be evaluated for pre-SBRT stabilization as it has been shown to mitigate the risk of VCF.65,66 Additionally, initiating of antiresorptive agents before SBRT may reduce the risk of post-SBRT VCF.67 Regardless, patients with VCF should be evaluated for treatment with a cement augmentation procedure, which has been shown to significantly improve pain and overall functioning over nonsurgical VCF management.68

Target Delineation

Optimal target delineation is paramount to the safe and effective delivery of spine SBRT. To facilitate this, consensus contouring guidelines have been published, which outline the best practice of target delineation across clinical scenarios including intact vertebrae, postoperative vertebrae, and the sacrum.69–71 From the International Spine Radiosurgery Consortium’s initial publication, each vertebral level was divided into 6 segments—the body, bilateral pedicles, bilateral transverse process/lamina, and the spinous process.69 The recommendation is that the clinical target volume (CTV) should include the gross disease (GTV), the entire involved anatomic segment and the adjacent anatomic segments (Figure 3).69 In the postoperative setting, the same concept is true, except that it is based on the preoperative extent of disease, superimposed on the postoperative anatomy.70 A similar concept holds in the sacrum except that it is divided into 8 anatomic segments including the body, bilateral anterior ala, bilateral posterior ala, bilateral lamina, and the spinous process (Figure 4). Once again, the CTV should be the entire segment(s) involved by the GTV and the adjacent anatomic segments.71

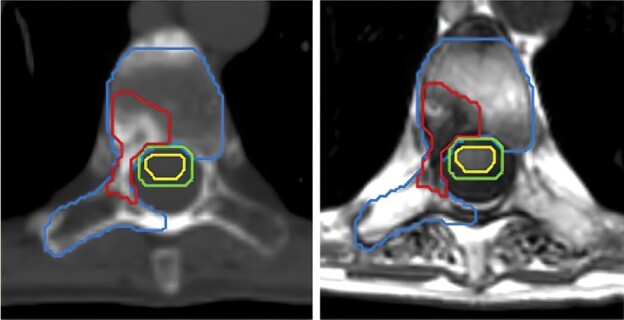

Figure 3.

Patient with a sclerotic bone metastases involving the vertebral body and right lamina. The gross tumor volume (GTV) is contoured in red, the cord in yellow and the 1.5 mm cord planning target volume (PTV) in green. In accordance with contouring guidelines, the entire vertebral body and ipsilateral lamina, transverse process and pedicle are included as clinical target volume (CTV; blue). The spinous process was not included as that can be optional when lamina is not involved.

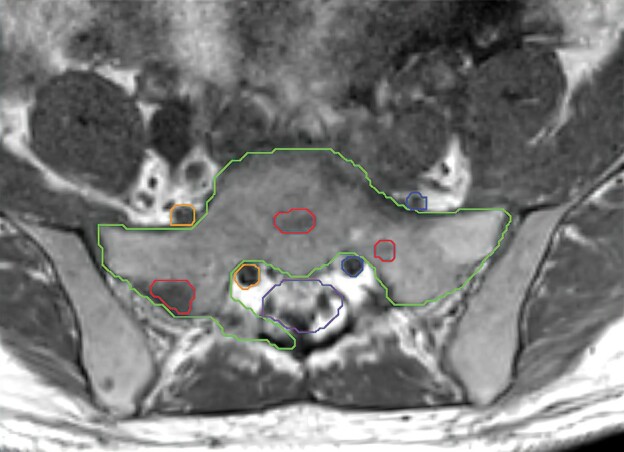

Figure 4.

Representative T1 unenhanced MRI slice demonstrating sacrum SBRT contours according to recent consensus guidelines.71 The gross tumor volume (red) involves segments 1, 2, 7, and 8 of the S1 vertebral body and the clinical target volume (green) includes segments 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 8. The thecal sac (purple) and bilateral nerve roots (orange and blue) are also contoured.

Equally important to target delineation, is precise delineation of the adjacent critical structures, most importantly the neural avoidance volumes. Above the conus, weighted volumetric MRI acquired in the axial plane typically shows the spinal cord well. In the context of significant artifact from surgical instrumentation, a CT myelogram may be required; however, optimally weighted T2 images typically overcome this invasive procedure. The expansion from the cord to the planning risk volume varies across institutions, and ranges from 0 to 2 mm depending on the practice. Utilizing the entire spinal canal as an avoidance structure should be avoided as this potentially increases the risk of local failure in the region, which is at baseline at the highest risk of local recurrence.

Below the conus, consensus contouring guidelines have been published for delineation of the thecal sac.72 In order to optimize target coverage, some many high-volume academic practices elect to contour the true sacral nerves and cauda equina and apply the normal tissue constraints to these less conservative volumes. However, for practices with less experience, following the consensus guidelines for thecal sac delineation may help to maintain safety and will be more forgiving to subtle errors in image fusion or patient setup.

Emerging data highlights the importance of careful adherence to the consensus contouring guidelines for CTV delineation. Specifically, a recent retrospective review demonstrates significantly superior local control when the consensus contouring guidelines are followed.73 Interestingly, this includes CTVs that are larger or smaller than dictated by the guidelines.

Response Assessment

The Spine Response Assessment in Neuro-oncology (SPINO) guidelines recommend MRI as the imaging modality of choice for response assessment following spine SBRT.74 The SPINO guidelines have defined progression as “unequivocal increase in the size of the tumor”74 with no specified growth threshold. In fact, currently, there are no globally accepted quantitative imaging-based guidelines to assess response following spine SBRT. Recent work has demonstrated that a 10.9% change in GTV is the minimum detectable difference on spine MRI.75 A recent report has also proposed a linear-based imaging measurement guideline, which needs to be verified with prospective multicenter data.76 MRI-based physiologic imaging using dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MR perfusion has also been investigated with several DCE metrics showing changes following spine SBRT.77,78 For example, in a pilot retrospective single-center study with a small sample size (30 patients recruited, 5 with progression), it was shown that plasma volume from DCE was predictive of tumor recurrence.78 Unfortunately, the technical details of DCE and postprocessing may not be easily generalizable to a broad array of practices. Several studies have also investigated the use of PET in response assessment following spine SBRT.79,80 PET has the advantage of direct metabolic imaging, which can potentially be more accurate than structural imaging for response assessment. A large-scale prospective study investigating the use of PET alone or in combination with MR perfusion could inform practice. An important consideration is that access to PET at every imaging follow-up time point may be difficult in clinical community due to availability, cost, and reimbursement practices.

A challenging aspect of MRI-based response assessment following SBRT is pseudoprogression, which has been defined by SPINO as transient increase in tumor size,74 which is like pseudoprogression in brain tumors following radiotherapy. There are only few reports in the literature addressing pseudoprogression following spine SBRT with a reported incidence of 14%–37%,81–83 occurring 3 weeks to 3 months following SBRT.84,85 A central challenge is the lack of criteria as to what constitutes pseudoprogression. Further complicating the matter, is the fact that time of onset of pseudoprogression is not yet known and can vary based on tumor histology and radiation dose.81

In recent years, non-imaging-based technologies to determine disease status have become popularized using liquid biopsy technologies.86,87 The premise of liquid biopsies is to interrogate tumor-derived material in biofluids such as plasma, urine, saliva, and CSF.88–90 For metastatic cancers, blood-based testing is likely to be the most informative as it allows analytes shed from throughout the body to be investigated. Some of the most common analytes being tested include circulating tumor DNA, circulating tumor cells, tumor-associated RNA, microvesicles, and proteins.91–93 Currently, the most robust data exist for detection and monitoring of cancers using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA).

Several studies have suggested that ctDNA can be used to monitor response therapy, including in lung, prostate, breast, and colon cancers.88,94–96 After definitive intent to cure in localized cancers, investigators have demonstrated that ctDNA can precede radiographic findings by 4–11 months.97,98 Most of these studies are focused on outcomes after surgery, chemotherapy, or combination therapy that includes radiation. Few reports are available for the monitoring after definitive radiation alone, such as SBRT.99 However, given the multiple reports demonstrating longitudinal ctDNA levels reflect treatment response, a compelling area of future research is to study how longitudinal ctDNA levels vary in individuals with solitary, oligo, and multimetastatic spinal cancers treated with SBRT.

Conclusions

Management of spinal metastases has been revolutionized over the last decade due to advances in SBRT and increasing utilization of minimally invasive surgical techniques. This has allowed vast improvements in local control using less invasive methods allowing faster recovery and more prompt return to systemic therapies. There is now randomized data showing superior local control with spine SBRT over cEBRT. Nonetheless, additional data are needed to identify the optimal dose/fractionation regimens to maximize local control and further improve upon pain control while minimizing toxicity, including VCF. As dose escalation is increasingly incorporated into clinical practice, novel imaging techniques to distinguish radiation-induced changes and pseudoprogression from true tumor progression will be imperative. The incorporation of serum biomarkers such as ctDNA into standard practice may ultimately play an important role in both optimization of treatment paradigms and response assessment.

Contributor Information

Amanda N Sacino, Department of Neurosurgery, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Hanbo Chen, Department of Radiation Oncology, Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Arjun Sahgal, Department of Radiation Oncology, Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Chetan Bettegowda, Department of Neurosurgery, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Laurence D Rhines, Department of Neurosurgery, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA.

Pejman Maralani, Department of Medical Imaging, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Kristin J Redmond, Department of Radiation and Molecular Oncology, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Supplement sponsorship

This article appears as part of the supplement “Pushing the Boundaries of Radiation Technology for the Central Nervous System,” sponsored by Varian Medical Systems.

Conflict of interest statement

H.C.: research grant from Elekta, speaker’s honorarium from Novartis. A.S.: consultant for Varian, Elekta (Gamma Knife Icon), BrainLAB, Merck, Abbvie, Roche; Vice President of the International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (ISRS), Co-Chair of the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Tumor; received honorarium for past educational seminars for AstraZeneca, Elekta AB, Varian, BrainLAB, Accuray, Seagen Inc, research grant with Elekta AB, Varian, Seagen Inc, BrainLAB, and travel accommodations/expenses with Elekta, Varian and BrainLAB, belongs to the Elekta MR Linac Research Consortium and is a Clinical Steering Committee Member, and chairs the Elekta Oligometastases Group and the Elekta Gamma Knife Icon Group. C.B.: consultant for Depuy-Synthes, Bionaut Lab, Haystack Oncology, Galectin Therapeutics and Privo Technologies and co-founder of OrisDx and Belay Diagnostics. P.M.: none. K.J.R.: research fundings from Canon, Elekta AB and Accuray, data safety monitoring board BioMimetix, contract being reviewed for research funding from icotec, radiogenomics patent under development with Canon.

References

- 1. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mossa-Basha M, Gerszten PC, Myrehaug S, et al. Spinal metastasis: diagnosis, management and follow-up. Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1103):20190211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laufer I, Rubin DG, Lis E, et al. The NOMS framework: approach to the treatment of spinal metastatic tumors. Oncologist. 2013;18(6):744–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fisher C, Ali Z, Detsky J, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of vertebral metastases: a phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5766–5776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dunne EM, Liu MC, Lo SS, Sahgal A.. The changing landscape for the treatment of painful spinal metastases: is stereotactic body radiation therapy the new standard of care? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2022;34(5):325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garg AK, Shiu AS, Yang J, et al. Phase 1/2 trial of single-session stereotactic body radiotherapy for previously unirradiated spinal metastases. Cancer. 2012;118(20):5069–5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Husain ZA, Sahgal A, De Salles A, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for de novo spinal metastases: systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(3):295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bilsky MH, Laufer I, Fourney DR, et al. Reliability analysis of the epidural spinal cord compression scale. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(3):324–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC, et al. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: an evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(22):E1221–E1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gilbert RW, Kim JH, Posner JB.. Epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic tumor: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1978;3(1):40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maranzano E, Bellavita R, Rossi R, et al. Short-course versus split-course radiotherapy in metastatic spinal cord compression: results of a phase III, randomized, multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3358–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rades D, Fehlauer F, Stalpers LJ, et al. A prospective evaluation of two radiotherapy schedules with 10 versus 20 fractions for the treatment of metastatic spinal cord compression: final results of a multicenter study. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2687–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller JA, Balagamwala EH, Angelov L, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of primary and metastatic spinal sarcomas. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017;16(3):276–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahmed AK, Goodwin CR, Heravi A, et al. Predicting survival for metastatic spine disease: a comparison of nine scoring systems. Spine J. 2018;18(10):1804–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alghamdi M, Sahgal A, Soliman H, et al. Postoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastases and the impact of epidural disease grade. Neurosurgery. 2019;85(6):E1111–E1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barzilai O, Laufer I, Robin A, et al. Hybrid therapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: technique for separation surgery and spine radiosurgery. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2019;16(3):310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laufer I, Iorgulescu JB, Chapman T, et al. Local disease control for spinal metastases following “separation surgery” and adjuvant hypofractionated or high-dose single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery: outcome analysis in 186 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(3):207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Massaad E, Shankar GM, Shin JH.. Novel applications of spinal navigation in deformity and oncology surgery-beyond screw placement. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2021;21(Supp 1):S23–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Solomiichuk V, Fleischhammer J, Molliqaj G, et al. Robotic versus fluoroscopy-guided pedicle screw insertion for metastatic spinal disease: a matched-cohort comparison. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;42(5):E13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molina CA, Dibble CF, Lo SL, Witham T, Sciubba DM.. Augmented reality-mediated stereotactic navigation for execution of en bloc lumbar spondylectomy osteotomies. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021;34(5):700–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tigchelaar SS, Medress ZA, Quon J, et al. Augmented reality neuronavigation for en bloc resection of spinal column lesions. World Neurosurg. 2022;167:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carl B, Bopp M, Sass B, et al. Spine surgery supported by augmented reality. Global Spine J. 2020;10(2 Suppl):41S–55S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molina CA, Dibble CF, Lo SL, Witham T, Sciubba DM.. Augmented reality-mediated stereotactic navigation for execution of en bloc lumbar spondylectomy osteotomies. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021;35:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kratzig T, Mende KC, Mohme M, et al. Carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK versus titanium implants: an in vitro comparison of susceptibility artifacts in CT and MR imaging. Neurosurg Rev. 2021;44(4):2163–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poel R, Belosi F, Albertini F, et al. Assessing the advantages of CFR-PEEK over titanium spinal stabilization implants in proton therapy-a phantom study. Phys Med Biol. 2020;65(24):245031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nevelsky A, Borzov E, Daniel S, Bar-Deroma R.. Perturbation effects of the carbon fiber-PEEK screws on radiotherapy dose distribution. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2017;18(2):62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muller BS, Ryang YM, Oechsner M, et al. The dosimetric impact of stabilizing spinal implants in radiotherapy treatment planning with protons and photons: standard titanium alloy vs radiolucent carbon-fiber-reinforced PEEK systems. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2020;21(8):6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Depauw N, Pursley J, Lozano-Calderon SA, Patel CG.. Evaluation of carbon fiber and titanium surgical implants for proton and photon therapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2023;13(3):256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cofano F, Di Perna G, Monticelli M, et al. Carbon fiber reinforced vs titanium implants for fixation in spinal metastases: a comparative clinical study about safety and effectiveness of the new “carbon-strategy”. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;75:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lindtner RA, Schmid R, Nydegger T, Konschake M, Schmoelz W.. Pedicle screw anchorage of carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK screws under cyclic loading. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(8):1775–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bruner HJ, Guan Y, Yoganandan N, et al. Biomechanics of polyaryletherketone rod composites and titanium rods for posterior lumbosacral instrumentation Presented at the 2010 Joint Spine Section Meeting. Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(6):766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sciubba DM, Pennington Z, Colman MW, et al. ; NASS Spine Oncology Committee. Spinal metastases 2021: a review of the current state of the art and future directions. Spine J. 2021;21(9):1414–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khan HA, Ber R, Neifert SN, et al. Carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK spinal implants for primary and metastatic spine tumors: a systematic review on implant complications and radiotherapy benefits. J Neurosurg Spine. 2023;39:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sprave T, Verma V, Förster R, et al. Randomized phase II trial evaluating pain response in patients with spinal metastases following stereotactic body radiotherapy versus three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2018;128(2):274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sprave T, Verma V, Forster R, et al. Local response and pathologic fractures following stereotactic body radiotherapy versus three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for spinal metastases—a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sahgal A, Myrehaug SD, Siva S, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy versus conventional external beam radiotherapy in patients with painful spinal metastases: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):1023–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zeng KL, Myrehaug S, Soliman H, et al. Mature local control and reirradiation rates comparing spine stereotactic body radiation therapy with conventional palliative external beam radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;114(2):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ryu S, Deshmukh S, Timmerman RD, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery vs conventional radiotherapy for localized vertebral metastases of the spine: phase 3 results of NRG Oncology/RTOG 0631 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(6):800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ryu S, Deshmukh S, Timmerman RD, et al. Radiosurgery compared to external beam radiotherapy for localized spine metastasis: phase III results of NRG oncology/RTOG 0631. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(1):S2–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rief H, Katayama S, Bruckner T, et al. High-dose single-fraction IMRT versus fractionated external beam radiotherapy for patients with spinal bone metastases: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16(1):264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chow E, Hoskin P, Mitera G, et al. ; International Bone Metastases Consensus Working Party. Update of the international consensus on palliative radiotherapy endpoints for future clinical trials in bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(5):1730–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ito K, Sugita S, Nakajima Y, et al. Phase 2 clinical trial of separation surgery followed by stereotactic body radiation therapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112(1):106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Redmond KJ, Sciubba D, Khan M, et al. A phase 2 clinical trial of separation surgery followed by stereotactic body radiation therapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(2):261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang XS, Rhines LD, Shiu AS, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for management of spinal metastases in patients without spinal cord compression: a phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zeng KL, Sahgal A, Husain ZA, et al. Local control and patterns of failure for “Radioresistant” spinal metastases following stereotactic body radiotherapy compared to a “Radiosensitive” reference. J Neurooncol. 2021;152(1):173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moraes FY, Mansouri A, Dasgupta A, et al. Impact of EGFR mutation on outcomes following SRS for brain metastases in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2021;155:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zeng KL, Abugarib A, Soliman H, et al. Dose-escalated 2-fraction spine stereotactic body radiation therapy: 28 Gy versus 24 Gy in 2 daily fractions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;115(3):686–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brown JM, Carlson DJ, Brenner DJ.. The tumor radiobiology of SRS and SBRT: are more than the 5 Rs involved? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(2):254–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McKenzie A, van Herk M, Mijnheer B.. Margins for geometric uncertainty around organs at risk in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2002;62(3):299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sahgal A, Chang JH, Ma L, et al. Spinal cord dose tolerance to stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110(1):124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kroeze SGC, Fritz C, Schaule J, et al. Continued versus interrupted targeted therapy during metastasis-directed stereotactic radiotherapy: a retrospective multi-center safety and efficacy analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(19):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee E, Chen X, LeCompte MC, et al. Safety and clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition and stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with spine metastasis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2023;39:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cox BW, Jackson A, Hunt M, Bilsky M, Yamada Y.. Esophageal toxicity from high-dose, single-fraction paraspinal stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):e661–e667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rose PS, Laufer I, Boland PJ, et al. Risk of fracture after single fraction image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy to spinal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(30):5075–5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sahgal A, Atenafu EG, Chao S, et al. Vertebral compression fracture after spine stereotactic body radiotherapy: a multi-institutional analysis with a focus on radiation dose and the spinal instability neoplastic score. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3426–3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Faruqi S, Tseng CL, Whyne C, et al. Vertebral compression fracture after spine stereotactic body radiation therapy: a review of the pathophysiology and risk factors. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(3):314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chen X, Gui C, Grimm J, et al. Normal tissue complication probability of vertebral compression fracture after stereotactic body radiotherapy for de novo spine metastasis. Radiother Oncol. 2020;150:142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zelefsky MJ, Yamada Y, Greco C, et al. Phase 3 multi-center, prospective, randomized trial comparing single-dose 24 Gy radiation therapy to a 3-fraction SBRT regimen in the treatment of oligometastatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110(3):672–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Soltys SG, Grimm J, Milano MT, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for spinal metastases: tumor control probability analyses and recommended reporting standards. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110(1):112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Perdomo-Pantoja A, Holmes C, Lina IA, et al. Effects of single-dose versus hypofractionated focused radiation on vertebral body structure and biomechanical integrity: development of a rabbit radiation-induced vertebral compression fracture model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;111(2):528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Saad F, Lipton A, Cook R, et al. Pathologic fractures correlate with reduced survival in patients with malignant bone disease. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1860–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee SH, Tatsui CE, Ghia AJ, et al. Can the spinal instability neoplastic score prior to spinal radiosurgery predict compression fractures following stereotactic spinal radiosurgery for metastatic spinal tumor?: a post hoc analysis of prospective phase II single-institution trials. J Neurooncol. 2016;126(3):509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gui C, Chen X, Sheikh K, et al. Radiomic modeling to predict risk of vertebral compression fracture after stereotactic body radiation therapy for spinal metastases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021;36:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jawad MS, Fahim DK, Gerszten PC, et al. ; on behalf of the Elekta Spine Radiosurgery Research Consortium. Vertebral compression fractures after stereotactic body radiation therapy: a large, multi-institutional, multinational evaluation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;24(6):928–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gestaut MM, Thawani N, Kim S, et al. Single fraction spine stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy with volumetric modulated arc therapy. J Neurooncol. 2017;133(1):165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Patel PP, Esposito EP, Zhu J, et al. Antiresorptive medications prior to stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastasis are associated with reduced incidence of vertebral body compression fracture. Global Spine J. 2023:21925682231156394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Berenson J, Pflugmacher R, Jarzem P, et al. ; Cancer Patient Fracture Evaluation (CAFE) Investigators. Balloon kyphoplasty versus non-surgical fracture management for treatment of painful vertebral body compression fractures in patients with cancer: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(3):225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cox BW, Spratt DE, Lovelock M, et al. International spine radiosurgery consortium consensus guidelines for target volume definition in spinal stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):e597–e605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Redmond KJ, Robertson S, Lo SS, et al. Consensus contouring guidelines for postoperative stereotactic body radiation therapy for metastatic solid tumor malignancies to the spine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(1):64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dunne EM, Sahgal A, Lo SS, et al. International consensus recommendations for target volume delineation specific to sacral metastases and spinal stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). Radiother Oncol. 2020;145:21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dunne EM, Lo SS, Liu MC, et al. Thecal sac contouring as a surrogate for the cauda equina and intracanal spinal nerve roots for spine stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT): contour variability and recommendations for safe practice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112(1):114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chen X, LeCompte MC, Gui C, et al. Deviation from consensus contouring guidelines predicts inferior local control after spine stereotactic body radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2022;173:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thibault I, Chang EL, Sheehan J, et al. Response assessment after stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastasis: a report from the SPIne response assessment in Neuro-Oncology (SPINO) group. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):e595–e603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jabehdar Maralani P, Tseng CL, Baharjoo H, et al. The initial step towards establishing a quantitative, magnetic resonance imaging-based framework for response assessment of spinal metastases after stereotactic body radiation therapy. Neurosurgery. 2021;89(5):884–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jabehdar Maralani P, Chen H, Moazen B, et al. Proposing a quantitative MRI-based linear measurement framework for response assessment following stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with spinal metastasis. J Neurooncol. 2022;160(1):265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vellayappan B, Cheong D, Singbal S, et al. Quantifying the changes in the tumour vascular micro-environment in spinal metastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy—a single arm prospective study. Radiol Oncol. 2022;56(4):525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kumar KA, Peck KK, Karimi S, et al. A pilot study evaluating the use of dynamic contrast-enhanced perfusion MRI to predict local recurrence after radiosurgery on spinal metastases. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017;16(6):857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tahara T, Fujii S, Ogawa T, et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography is a useful predictor of long-term pain control after palliative radiation therapy in patients with painful bone metastases: results of a single-institute prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94(2):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ozdemir Y, Torun N, Guler OC, et al. Local control and vertebral compression fractures following stereotactic body radiotherapy for spine metastases. J Bone Oncol. 2019;15:100218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jabehdar Maralani P, Winger K, Symons S, et al. Incidence and time of onset of osseous pseudoprogression in patients with metastatic spine disease from renal cell or prostate carcinoma after treatment with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(3):647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Amini B, Beaman CB, Madewell JE, et al. Osseous pseudoprogression in vertebral bodies treated with stereotactic radiosurgery: a secondary analysis of prospective phase I/II clinical trials. Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(2):387–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bahig H, Simard D, Letourneau L, et al. A study of pseudoprogression after spine stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(4):848–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Taylor DR, Weaver JA.. Tumor pseudoprogression of spinal metastasis after radiosurgery: a novel concept and case reports. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;22(5):534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Al-Omair A, Smith R, Kiehl TR, et al. Radiation-induced vertebral compression fracture following spine stereotactic radiosurgery: clinicopathological correlation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(5):430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mattox AK, Bettegowda C, Zhou S, et al. Applications of liquid biopsies for cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(507):eaay1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Moding EJ, Nabet BY, Alizadeh AA, Diehn M.. Detecting liquid remnants of solid tumors: circulating tumor DNA minimal residual disease. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(12):2968–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wang Y, Springer S, Zhang M, et al. Detection of tumor-derived DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with primary tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(31):9704–9709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chow LS, Gerszten RE, Taylor JM, et al. Reply to “Lactate as a major myokine and exerkine”. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(11):713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Crowley E, Di Nicolantonio F, Loupakis F, Bardelli A.. Liquid biopsy: monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(8):472–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ring A, Nguyen-Strauli BD, Wicki A, Aceto N.. Biology, vulnerabilities and clinical applications of circulating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23(2):95–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yu W, Hurley J, Roberts D, et al. Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: opportunities and challenges. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(4):466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Herberts C, Annala M, Sipola J, et al. ; SU2C/PCF West Coast Prostate Cancer Dream Team. Deep whole-genome ctDNA chronology of treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2022;608(7921):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1199–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Tie J, Cohen JD, Lahouel K, et al. ; DYNAMIC Investigators. Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(24):2261–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. McEvoy AC, Pereira MR, Reid A, et al. Monitoring melanoma recurrence with circulating tumor DNA: a proof of concept from three case studies. Oncotarget. 2019;10(2):113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Tarazona N, Gimeno-Valiente F, Gambardella V, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of circulating-tumor DNA for tracking minimal residual disease in localized colon cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(11):1804–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Colosini A, Bernardi S, Foroni C, et al. Stratification of oligometastatic prostate cancer patients by liquid biopsy: clinical insights from a pilot study. Biomedicines. 2022;10(6):1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]