Abstract

Intracranial tumors include a challenging array of primary and secondary parenchymal and extra-axial tumors which cause neurologic morbidity consequential to location, disease extent, and proximity to critical neurologic structures. Radiotherapy can be used in the definitive, adjuvant, or salvage setting either with curative or palliative intent. Proton therapy (PT) is a promising advance due to dosimetric advantages compared to conventional photon radiotherapy with regards to normal tissue sparing, as well as distinct physical properties, which yield radiobiologic benefits. In this review, the principles of efficacy and safety of PT for a variety of intracranial tumors are discussed, drawing upon case series, retrospective and prospective cohort studies, and randomized clinical trials. This manuscript explores the potential advantages of PT, including reduced acute and late treatment-related side effects and improved quality of life. The objective is to provide a comprehensive review of the current evidence and clinical outcomes of PT. Given the lack of consensus and directives for its utilization in patients with intracranial tumors, we aim to provide a guide for its judicious use in clinical practice.

Keywords: brain tumors, CNS tumors, proton therapy

Key Points.

- Proton therapy (PT) delivers highly targeted radiation to central nervous system (CNS) tumors, minimizing damage to surrounding healthy brain tissue.

- Compared to conventional photon radiation, PT shows potential for reducing long-term neurocognitive deficits and improving quality of life.

- PT has demonstrated effectiveness in treating difficult-to-reach or recurrent CNS tumors, making it a valuable option for such complex cases.

Radiation therapy (RT) plays an important role in the management of intracranial parenchymal or extra-axial cerebral and skull-base tumors, serving as a definitive, adjuvant, or salvage treatment for curative or palliative intent. Contemporary clinical consensus guidelines lack details regarding the utilization of specific RT techniques, such as the consideration of particle therapy (ie, proton therapy [PT]). Moreover, although traditional photon-based RT is broadly available, PT currently accounts for fewer than 1% of all RT treatments delivered.1 This presents a logistical challenge to its incorporation into international treatment guidelines, although, with the recent rapid global expansion of PT centers, this deserves reevaluation (Supplementary Figure 1).

The distinctive physical feature of PT is the sharply defined “Bragg peak” which deposits the majority of the RT dose in the tumor; the dose decreases rapidly to zero within a few millimeters beyond this peak, setting it apart from photon RT.2 Passively scattered PT, a “first generation” technique and now largely antiquated, requires custom physical devices to shape the beam. The contemporary approach of intensity-modulated PT (IMPT) uses spot-scanning or “pencil” beam delivery to produce a narrower proton beam that is magnetically scanned to cover one layer of the target. The depth is controlled by modulating the beam energy, so that multiple spots in multiple layers treat the entire volume. IMPT is a newer technique compared to passively scattered PT and has many distinct advantages; novel delivery forms of IMPT, such as spot-scanning proton arc therapy (SPArc), and ultra-high-dose-rate delivery (FLASH) are in development.

With PT, the rapid dose-fall-off reduces the dose to the brain outside the target volume, and in the case of nearby structures (ie, temporal lobes, hippocampus, etc.), this can translate into improved functional, endocrine, and cognitive preservation as well as improved quality of life, crucial for those with an expectation of long-term survival.3,4 Nonetheless, in a prospective neurocognitive study involving 20 patients diagnosed with supratentorial low-grade gliomas (LGGs) treated with doses of 50.4 or 64.8 Gy using photon RT, there was no detriment of the neurocognitive function, even in the experimental arm with dose-escalation.5 The dosimetric benefits of PT also include reduction in severe radiation-induced lymphopenia (RIL), due to the reduction in dose to circulating blood through the cranium. This is particularly important for conditions requiring concomitant chemoradiotherapy, or large-field irradiation, such as leptomeningeal disease (LMD) treated with craniospinal irradiation (CSI).6 Another benefit to PT over photon RT is the decreased risk of secondary malignancy, critical for pediatric and adult patients with benign tumors or those with long natural histories.7 These radiobiologic and dosimetric properties warrant consideration of PT in multiple intracranial parenchymal and extra-axial cerebral and skull-base tumor types.

As an advanced RT technique, particle therapies, such as PT have several technique-related considerations. First, in terms of accessibility, there is a limited number and overall geographic maldistribution of PT units worldwide, with only 105 operational facilities as of May 2023, and 44 of these located in 23 states in the United States.8 The high costs associated with establishing and operating PT facilities, which can be 2 to 20 times more expensive than standard photon facilities, also present a significant obstacle to broad adoption and utilization.9 Second, in terms of insurance coverage in the United States, the implementation of prior authorization requirements in adults presents a notable obstacle, with 63% of initial requests resulting in denials (42% after appeal) given the lack of randomized level 1 evidence, including for many central nervous system (CNS) tumors. Insurance delays may impact patient care and treatment timelines,10 and certain brain tumors have important timing windows from surgery to treatment to ensure optimal outcomes.11 Third, PT plan evaluation requires additional review of particle therapy-specific factors, in addition to the standard metrics used in photon therapy, such as beam arrangement, beam modulation, spot placement, and plan robustness (Supplementary Table 1).12 Additionally, the lack of standardization of relative biological effectiveness and linear energy transfer plan evaluation tools for PT poses significant challenges in treatment planning. The absence of universally agreed-upon standards for relative biological effectiveness and linear energy transfer calculations leads to variations across different institutions and complicates the comparison of treatment outcomes.13,14 These unknowns have been underscored by the observation of particle therapy-specific effects on the brain such as radiation-induced contrast enhancement, an unexpected appearance of contrast enhancement distal to the target volumes and typically periventricular in location in adults with low-grade gliomas (Supplementary Figure 2) as well as brainstem injury in patients with posterior fossa tumors treated with PT.15,16

Despite the promising advantages of PT, there is a lack of consensus and standardization in its clinical application and utilization. This manuscript aims to provide a comprehensive guide for the judicious use of PT in intracranial tumors, covering patient selection, clinical evidence, and dose and fractionation for a variety of indications.

Primary Intracranial Parenchymal Tumors

Gliomas

Maximal safe resection is considered the upfront standard of care approach and individualized decisions of adjuvant therapies, including RT, are made based on the extent of residual tumor, symptoms, tumor size, risk profile, and molecular tumor characteristics. When adjuvant RT is utilized for patients with gliomas, the available data on tumor control with PT directly compared to other techniques is limited; however, the majority of studies demonstrate higher local control rates than traditionally observed with photon therapy yet given the selection bias and lack of randomized comparisons, no definitive conclusions can be made. Also, PT has been associated with modest treatment-related toxicities and numerically lower than those observed with photon therapy (Table 1).6,24

Table 1.

Selected Series of Proton Therapy for Patients With Low or High-Grade Gliomas.

| Author, year (Study type) | RT Purpose | n | WHO grade or histology | Molecular profile | Target volume definitions | Volume (cc) | RT modality | PT specifications | Prescribed dose (GyRBE) | mFU | Outcomes | AE/ comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tsujii et al. 199317 (P) |

A | 13 | AA or GBM | NR | GTV1 = C + and surrounding low density (CT) GTV2 (boost) = only C + (CT) |

NR | XRT + PT Boost or PT Alone |

NR |

Proton alone:

66.8 (50–76) [2.8(2.5–3.5)/fx] Proton boost: 43–55 Gy |

NR | mOS: 20 m | 4 RN (2 died) |

|

Hauswald et al., 201218 (R) |

S | 19 | 1, 2 | NR | GTV = T2-hyperintensity + PET-positive regions CTV = GTV + 1–2 cm PTV = CTV + 3 mm. |

99 cc (range: 6–463 cc) | Only PT | Fixed beam line with non-coplanar beams in active raster-scanning technique |

52.2 (range: 48.6–54) [1.8–2/fx] |

5 m (0-22 moths) | 12 SD, 2 CR, 1 progression | Acute toxicity: 13 alopecia, 6 mild fatigue, 1 concentration deficit, 1 short-term deficits |

|

Greenberger et al., 201419 (R) |

A, D | 32 | 1, 2 | NR | GTV = resection cavity + gross disease visible on MRI or CT CTV = GTV + 3-5 mm |

NR | Only PT (23) XRT + PT (9) |

NR | 52.2 (range: 48.6–54) [1.8/fx] |

7.6 y | 8-y PFS 82.8% 8-y OS 100% |

Includes pediatric population (median age 11y) 2 spinal gliomas, 30 intracranial |

|

Shih et al., 201520 Sherman et al., 201621 (P) |

A (12) R (8) |

20 | 2 | GTV = T2 hyperintense residual tumor, resection cavity that abutted the tumor and any potential T1 Gd+ CTV = GTV + 1.5cm (considering surrounding anatomy) |

Volume NR 9 small (<6 cm) 11 large (≥6 cm) |

Only PT | NR | 54 [1.8 per fx] |

5 y | 1, 3 and 5-y PFS: 100, 85, 40% 1, 3 and 5-y OS: 100, 95, 84% |

Neurocognitive Remained largely stable (P < .05) By tumor hemisphere side: Baseline verbal measures impairment: Left > right (P < .05) Verbal memory recovery over time: Left > Right (P < .05). |

|

|

Wilkinson et al., 201622 (ASTRO) (P) |

A (47) D (1) |

48 | 2 | NR | NR | NR | Only PT | NR | 50.4 and 54 (78%) | NR | NR | No grade 3 + reported |

|

Tabrizi et al., 201923 (P) |

A | 20 | 2 | 71% (IDH1-R132H mutation) 29%(1p/19q co-deletion) |

GTV = composite MRI T2-hyperintense tumor + any T1-Gd+ CTV = GTV + 1.5 cm |

NR | Only PT | PSPT (robustness: 3.5% and 1 mm uncertainty) |

54 [1.8 per fx] |

6.8 y | median PFS 4.5 y 10-y PFS 37% 10-y OS 69% |

Neuroendocrine

6 (30%): 4 adrenal, 3 central hypothyroidism and 2 men central hypogonadism Median neuroendocrine deficiency 10.9 m Neurocognitive No overall decline |

|

Mohan et al., 2021

6

Brown et al., 2021 24 NCT01854554 (P) |

A |

26 (protons)

41 (IMRT) |

GBM |

10% (IDH-1 mutation)

25% (MGMT methylated) |

GTV = tumor cavity and any residual T1 Gd+

CTV = GTV + 2-cm expansion with consideration of the surrounding anatomy PTV50 = CTV + 3–5 mm PTV60 (“ boost” ) = GTV + 3–5 mm |

Proton arm:

GTV = 40.1 (3.9, 133.8) CTV = 215.6 (31.4, 404.4) |

XRT vs. PT | PSPT (7)/ IMPT (19) |

50 GyRBE + 60 GyRBE (SIB)

[30fx] |

48.7 m (7.1–66.7 months) |

Comparing IMRT vs. proton

PFS (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.44–1.23; P = 0.24) OS (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.49–1.50; p = 0.60). |

Neurocognitive failure (primary endpoint): No difference in time to cognitive failure (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.45–1.75; P = .74).

Grade 2± toxicity: IMRT mean 1.15 (range:0–6); PT mean 0.35 (range 0–3, P = .02) Comparing PT to IMRT. Concomitant TMZ |

n, number of patients; mFU, median follow-up; cc, cubic centimeters; mm, millimeters; PSPT, Passively scattering proton therapy; (P), Prospective; (R), retrospective; D, definitive; A, adjuvant; S, salvage (recurrence/progression); XRT, photon radiation therapy; PT, proton therapy; PFS, progression-free survival; ORR, Objective response rate, CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; LC, local control OS, overall survival; AE, adverse effects; NR, Not reported; CN, cranial nerve; WHO, World Health Organization; GTV, Gross tumor volume; CTV, Clinical target volume; PTV, Planning target volume; SIB, Simultaneous integrated boost; ON, Optic nerve; IMRT, Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy; RN, radiation necrosis; fx, fraction; C+, contrast-enhanced.

Low-grade glioma

Level 1 evidence supporting the role of adjuvant RT in a combinatorial regimen for patients with LGGs is available from RTOG 9802 which demonstrated that RT followed by procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) for grade 2 oligodendrogliomas (IDH-mutated, 1p19q co-deleted) and grade 2 astrocytomas (IDH-mutated, 1p19q intact) improved survival. RTOG 9402 supported the role of PCV followed by RT for grade 3 oligodendrogliomas (IDH-mutated, 1p19q co-deleted), and the CATNON study supported the role of RT followed by temozolomide for grade 3 astrocytomas (IDH-mutated, 1p19q intact). Given the long median survivals ranging from 9.7 years for grade 3 astrocytomas (IDH-mutated, 1p19q intact) to > 14 years for grade 2 oligodendrogliomas (IDH-mutated, 1p19q co-deleted), important considerations with regards to acute and late toxicities have prompted the investigation of PT in these patient subgroups.

One of the major concerns with intracranial RT is decline in neurocognition. Previous non-randomized studies have demonstrated decline in overall neurocognitive function, specific individualized domain effects (executive functioning, psychomotor functioning, working memory, information processing speed, and attention),25 and delays in improvement compared to systemic therapy alone.26 It is important to note that level 1 evidence exists for fractionated stereotactic RT delivery techniques compared to conformal RT in reducing the risk of neurocognitive, endocrine, and intellectual dysfunction4; from a dosimetric standpoint, PT represents a natural extension of this evidence. This is indirectly supported by a prospective study in 20 patients with LGGs (71% IDH-mutated, 29% 1p19q co-deleted) treated with PT, and after 5-years of follow-up, no decline in neurocognition was observed in a multi-dimensional battery of cognitive tests.20,21 Moreover, early promising results from the REGI-MA-002015 trial (NCT03049072), showed neurocognitive function preservation after 1 year in 90% of patients treated with PT for intracranial tumors (13 patients had grade 2/3 gliomas).27 Finally, a retrospective exploratory study of PT for adults with intracranial tumors (a significant proportion of patients had glioma as a diagnosis) also demonstrated the stability of neurocognitive measures (assessed with the montreal cognitive assessment [MoCA]).3 The ongoing NRG BN005 (NCT03180502) phase 2 clinical trial randomizes such patients to photon RT or PT (with adjuvant temozolomide) with the primary endpoint of change in cognition. The PRO-GLIO phase 3 trial (NCT05190172) also compares PT with photon RT for patients with IDH-mutated diffuse grade 2–3 gliomas, where the first intervention-free survival at 2 years is the primary endpoint.28

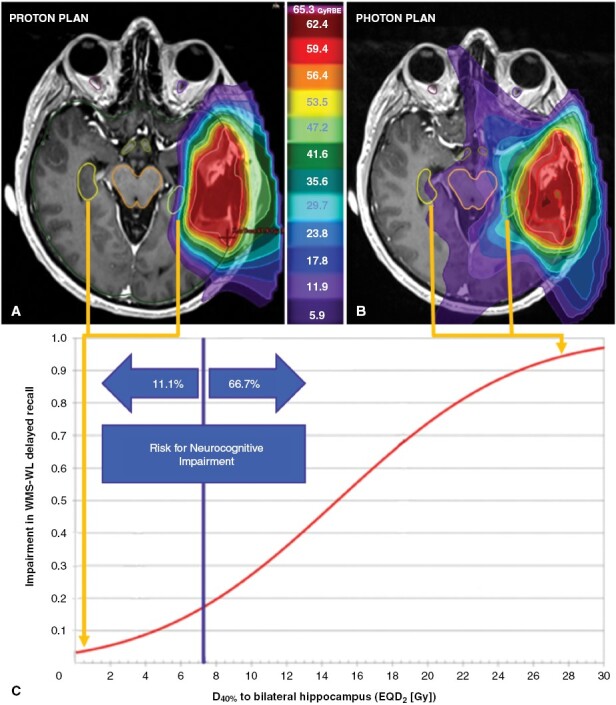

In current clinical practice, dosimetric models, such as hippocampal dose and predicted impairment on the Wechsler Memory Scale-III Word List (WMS-WL), can be used to evaluate RT plans using pre-determined metrics (ie, D40% > 7.3 Gy [EQD2])29; an example is shown in Figure 1. Dosimetric constraints for the dominant hippocampus, unilateral or bilateral temporal lobes, and other substructures associated with neurocognition have been well studied and can provide objective measures of the potential benefits of a particular RT technique, including PT.30 Additionally, patients receiving systemic therapy are at a high risk for RIL, and patient-specific risk variables such as female gender, low baseline absolute lymphocyte counts, diffuse disease, and high integral brain doses have a correlative association,6 and could be considered in the PT-selection decision-making (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Case example illustrating the dose to bilateral hippocampus for patient with a left temporal glioma. (A) Intensity-modulated proton therapy treatment plan with isodose distribution and bilateral hippocampus delineated (B) demonstrates a substantially lower risk of neurocognitive impairment than a photon therapy plan (non-coplanar volumetric modulated arc therapy [VMAT]) with isodose distribution (C) due to the rapid dose-fall at the (left) ipsilateral hippocampus and lack of exit or entrance dose at the contralateral (right) hippocampus. Adapted from Gondi et al.,29 dose–response relationship from Wechsler Memory Scale-III World Lists (WMS-WL) Delayed Recall at 18 months and the dose to 40% of bilateral hippocampus. Footnote: EQD2 = equivalent total dose in 2-Gy fractions. WMS-WL = Wechsler Memory Scale-III World Lists. Gy = Gray. RBE = relative biological effectiveness

Table 4.

Evidence-Based Recommendations for the Use of Proton Therapy for Intracranial Parenchymal and Extra-Axial Cerebral and Skull-Base Tumors

| CNS tumor | Classification | When to consider proton therapy | Dose (GyRBE) | Level of evidence (PT) | References | ASTRO model policy group 1*,99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary intracranial parenchymal tumors | ||||||

| Glioma | Low-grade | Young patients (Reduce long-term toxicity) Reduce acute treatment-related toxicities (radiation-induced lymphopenia) |

45–54 (1.8–2/fraction) | Adjuvant, salvage: 2 | Hauswald etal.18 Greenberger et al.19 Shih et al.20 Sherman et al.21 Eekers et al.100 Dennis et al.101 Harrabi et al.102 Flechl et al.27 Wilkinson et al.22 Tabrizi et al.23 |

YES |

| High-grade | Reduce acute treatment-related toxicities (radiation-induced lymphopenia) | 60 (2/fraction) | Adjuvant: 2 | Brown et al.24 Mallick et al.103 Mohan et al.6 Adeberg et al.32 Tsujii et al.17 |

NO | |

| Primary intracranial extra-axial tumors | ||||||

| Meningioma | WHO grade 1 | Challenging locations [ie, BoS] Young population (Reduce late treatment-related toxicity and secondary tumors risk) |

50.4-–54 (1.8–2/fraction) | Definitive, adjuvant: 3 Salvage: 5 |

Vernimmen et al.39 Holtzman et al.,48 El Shafie et al.47 Florijn et al.104 |

YES |

| 13 (single fraction) | Definitive: 4 | Halasz et al.,38 | ||||

| WHO grade 2/3 | Challenging locations (close to critical structures) Tumor control (dose escalation) Reduce treatment-related toxicity |

Grade 2: 54–68.4 (1.8/fraction) Grade 3: 59.4–72 (1.8/fraction) |

Definitive, adjuvant, salvage: 3 | Chan et al.51 Weber et al.42 Weber et al.43 Slater et al.44 McDonald et al.45 Murray et al.46 |

YES | |

| Craniopharyngioma | - | Reduce late treatment-related toxicity and secondary tumors risk | 50.4–59.4 GyRBE (1.8/fraction) | Adjuvant: 2 | Merchant et al.58 | YES |

| Pituitary adenoma | - | Challenging locations (close to critical structures) Reduce treatment-related toxicity |

PSRS: 20GyRBE for FPA, 17 GyRBE for NFA Consider PSRS when target is 3-5mm from optic chiasm and < 3 cm in diameter |

Definitive, adjuvant, salvage: 4 | Ronson et al.105 Petit et al.62 Wattson et al.65 |

YES |

|

Fractionated:

NFA: 45–50.4 (1.8/fraction) FPA: 50.4–54 (1.8/fraction) |

Definitive (NFA), adjuvant, salvage: 4 | YES | ||||

| Vestibular schwannoma | - | Potential treatment-related toxicity risk reduction |

PSRS: 12 GyRBE Consider PSRS for < 15 cc |

Definitive, adjuvant, salvage: 3 | Harsh et al. 67 Chan et al.68 |

YES |

| 45–50.4 (1.8/fraction) | Definitive, adjuvant, salvage: 4 | Chan et al.68 | ||||

| Primary extra-axial skull-base tumors | ||||||

| Chordoma chondrosarcoma |

dose escalation (tumor control) challenging locations [close to critical structures] |

63-78.4 (1.8–2/fraction) | Definitive, adjuvant: 3 | Palm et al.75 Nie et al.70 Rosenberg et al.79 Weber et al82,87 Ares et al.72 Grosshans et al. 85 Hottinger et al.89 Iannalfi et al.90 |

YES | |

| Secondary malignancies of the central nervous system | ||||||

| Leptomeningeal disease | Reduce acute treatment-related symptoms (nausea/vomiting, esophagitis, fatigue, and among others) Reduce risk of myelosupression |

30 GyRBE/10 fractions | Palliative: 1 | Brown et al.106 Yang et al.107 Yang et al.108 |

YES | |

| Re-irradiation | ||||||

| Re-irradiation | Reduce treatment-related toxicity from overlapping OARs | Consider the histology | Salvage, palliative: Depending on histology | Simone et al109 Saeed et al.110 El Shafie et al.111 Eaton et al112 |

YES § | |

CNS, , entral nervous system; GyRBE, Gray relative biological effectiveness; ASTRO, American Society for Radiation Oncology; WHO, World Health Organization; BoS, base of skull; mm, millimeter; cc, cubic centimeters; QoL, quality of life; PS, performance status; PSRS, proton stereotactic radiosurgery; SIB, Simultaneous integrated boost; FPA, Functional pituitary adenoma; NFA, nonfunctional pituitary adenoma; SPT, stereotactic proton therapy.

*ASTRO categorized proton beam therapy clinical indications into group 1, for which health insurance coverage is recommended, and group 2, for which coverage is recommended only if additional clinical requirements are met.

Level of evidence description: 1 (High): Well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses, which provide the most robust evidence. 2 (Moderate): non-randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or case–control studies. 3 (Low): case series and other observational studies. Grade 4 (Very low): Expert opinions, case reports, or uncontrolled studies. 5 (Conflicting or inconclusive): Conflicting results, making it difficult to draw a definitive conclusion.

*Group 1 = Medically necessary.

§if cumulative critical structure dose would exceed tolerance.

High-grade glioma

The current standard of care for patients with newly diagnosed GBM includes maximal safe resection followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant temozolomide with consideration of adjuvant Tumor Treating Fields. Despite this multimodal approach, the majority of recurrences are local, and the overall outcome remains poor. Therefore, PT has been investigated as a means of dose-escalation, to overcome this radioresistance, change the pattern of disease relapse, decrease lymphopenia, and potentially improve survival. Several series have demonstrated the safety, neurocognitive outcomes, quality of life, reduction in lymphopenia, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS of PT in patients with high-grade gliomas (primarily GBM).31-33 Collectively, the tumor control rates appear similar to historical series32 and survival outcomes are unable to be directly compared given the patient selection biases. A phase 2 signal-seeking trial randomized GBM patients to photon RT versus PT (with standard dosing), with the primary endpoint of time to cognitive failure.24 Although there was no difference in this endpoint, or overall quality of life, PT was associated with reduced fatigue (clinically significant difference of 24% vs. 58%, not reaching statistical significance [P = .05]), lower rates of grade 2 + toxicities (23% vs. 49%, P = .06), and reduced risk of acute severe lymphopenia (14% vs. 39%, P = .02).6,34 The results of the recently completed NRG-BN001 (NCT02179086) randomized clinical trial comparing dose-escalated PT (75 GyRBE in 30 fractions) vs. standard dose photon RT (60 Gy in 30 fractions) for newly diagnosed GBM are awaited.

Given the currently available data, we do not recommend the routine use of PT for high-grade gliomas (awaiting BN001 results to clarify). In rare circumstances when patients are at high risk of RIL and are receiving intensive systemic therapy, PT can be considered on an individual-patient basis. Whether the legacy “lower grade” non-enhancing gliomas that are upgraded to molecular grade 4 gliomas, and often occur in younger patients, in close proximity to critical radiosensitive brain structures should be treated with PT, is an issue for therapeutic individualization.

Primary Intracranial Extra-Axial Tumors

Meningioma

Meningiomas are the most common primary adult intracranial tumor. For patients with World Health Organization (WHO) grade 1 progressive meningioma, RT can be used as a definitive treatment as an alternative to resection, selectively employed in the adjuvant setting for those at high risk of tumor recurrence, and often relied upon as salvage for those with relapse. Conventionally fractionated RT, hypofractionated stereotactic RT (HSRT), and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) are used for patients with grade 1 meningiomas in the definitive setting. The International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (ISRS) consensus guidelines support the role of SRS (12–15 Gy, single fraction) with a recommendation level of 2, and hypofractionated schedules (25 Gy in 5 fractions) have been used for large tumors (≥3 cm) or those close to critical OARs. For those with WHO grade 2 tumors, RT can be used in the definitive, adjuvant, or salvage setting, and RT is near-universally used in the adjuvant setting for patients with WHO 3 tumors.35 For these patients, conventionally fractionated photon RT was used on the RTOG 0539 and EORTC 22042–26042 studies (54–60 Gy) and is most commonly used; SRS or hypofractionated techniques in these patients have demonstrated mixed outcomes and are not supported by consensus guidelines.36,37

WHO grade 1 meningiomas

PT has been utilized in the definitive setting for patients with WHO 1 meningiomas using a variety of techniques, including proton stereotactic radiosurgery (PSRS),38 hypofractionated schedules,39,40 or more conventionally fractionated treatments, with excellent local control (Table 2).43,45,47 It is important to note that hypofractionated treatments or those delivered using older forms of PSRS were associated with higher rates of adverse events than would be expected with traditional photon RT techniques.39 In a recent prospective study reporting long-term results of PT for WHO grade 1 meningiomas treated with definitive or adjuvant RT to a median dose of 50.4 GyRBE (range 48.6–61.2 GyRBE), with median follow-up of 6.3 years, the 5-year local progression rate was only 6% and the grade 3 + toxicity rate was 2%.48 In another exploratory retrospective study, neurocognitive function remained stable over a long follow-up period with the use of PT, as assessed using the MoCA.3 In the REGI-MA-002015 trial (NCT03049072), where > 60% of enrolled patients had meningioma, neurocognitive function was preserved in > 90% of patients treated with PT.27 Therefore, although based primarily on retrospective evidence and two prospective non-comparative studies, PT could be considered in those with challenging tumor locations, for example, the base of skull, where a dosimetric advantage to a critical neurologic organ-at-risk (OAR) or neurocognitive substructure can be observed,29,30,49 to reduce the risk of treatment-related toxicity or secondary malignancy given the long-term natural history of the disease (Table 4).

Table 2.

Selected Series of Proton Therapy for Patients With Intracranial Meningiomas

| Author and Year (Study Type) |

RT Purpose | np (nles) | WHO grade | Tumor location |

Target definition and volumes (cc) | Type of PT | Prescribed Dose (GyRBE) | mFU | Outcomes/AE/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gudjonsson et al. 199941 (P) |

D (4) A (15) |

19 | 1 | BoS | GTV (macroscopic tumor defined in CT) PTV = GTV + 5 mm Median GTV: 14 cc (range 2-53 cc) |

NR | HSRT: 20, 24 [5, 6/fx] | 36 m | 3-y LC 100% 2 RN (grade non described) |

| Vernimmen et al., 200139 (R) |

NR | 23 | 1 | All | HSRT: GTV 15.6 cc (range 2.6-63 cc) SRT: GTV 43.7 cc (range: 13.5-80 cc) |

PBS | HSRT (n = 18): 16.3 SRT (n = 5): 54 [2/fx] 61.6 [3.9/fx] |

Clinical 40 m Imaging 31 m |

HSRT: ORR 88% (23% CR, 6% PR, 59% SD). 12% (2 patients) progressed SRT: all patients stable (5) Acute toxicity: HSRT 11% (n = 2) transient CN neuropathy. SRT (n = 1) III CN palsy. Late toxicity: HSRT: 11% (n = 2): ipsilateral partial hearing loss, temporal lobe epilepsy. SRT: NR HSRT (3 fractions) SRT (16 + fractions) |

| Weber et al., 200442 (R) |

D (3) A (8) S (5) |

16 | All | BoS | median 17.5 cc (0.8-87.6 cc) | SSPT | 56 (52.2–64) [1.8–2.0/fx] | Imaging 34 m | 3-y LC 91.7, 3-y PFS 91.7% 3-y OS 92.7% ORR 18.6% and SD 75% 3-y toxicity free survival 76.2% (1 grade 4 RN) |

| Halasz et al., 201138 (R) |

D (32) A (8) S (10) |

50 (51) | 1 | All | Median 2.1 cc (0.-9.7 cc) | NR | 13 (10.0-15.5) | 32 m | 3-y tumor control rate 94% (95% CI:77%-98%). 90% local control. 65% SD; 25% decreased and 10% increased size. 3 (5.9%) developed permanent AE treatment related (2 seizures with brain edema, 1 panhypopituitarism) |

| Weber et al., 201243 (R) |

D (8) A (25) S (6) |

39 | 1(23), 2(9), 3(2) | BoS (82%) | GTV (macroscopic tumor defined in CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + 0-10 mm PTV = CTV + 4-6 mm Median 21.5 cc (range 0.76-546.5 cc) |

SSPT | WHO grade 1: 52.2 (favorable); 54 (intermediate), 56 (unfavorable) GyRBE WHO grade 2/3: 60.8 (55.5-66.1 GyRBE) |

4.6 y | 5-y OS 81.8% 5-y LC 84.8% 5-y grade 3 + free survival 84.5% |

| Slater et al., 2012 44 (R) |

D (22) A (30) S (20) |

72 | 1(47), 2 + (25) | BoS (23) | GTV (enhancing tumor) CTV = GTV + 5mm “ PTV” = 3 mm uncertainty mean GTV 27.6 cc mean CTV 52.9 cc |

NR | WHO grade 1: 50.4-66.6 Gy (1.8 GyRBE/fx) WHO grade 2: 54-70.4 Gy |

74 m | 5-year actuarial control rate 96% (99% for WHO grade 1) Neurological (n = 6) Visual (n = 3) (ON received full dose) |

| McDonald et al., 201545 (R) |

A (12) S (10) |

22 | 2 | All | GTV = tumor bed CTV = GTV + 0.5-1cm PTV = CTV + 2mm |

PSPT | 63 GyRBE (range: 54–68.4 GyRBE) | 39 m (7–104) | 5-y LC 87.5% (>60 GyRBE) vs. 50% (≤50 GyRBE) (p = 0.038) 1 patient RN (prior RT) |

| Murray et al., 201746 (R) |

D + A (53) S (43) |

96 | 1(61), 2(33), 3(2) | BoS (64) | GTV (enhancing tumor) CTV = GTV + 1-5mm (grade 1) or + 10 mm (grade 2+) PTV = 4-6 mm GTV 21.4 cc (0-546.51 cc) |

PBS | WHO grade 1: 54GyRBE (range, 50.4-64 GyRBE) WHO grade2/3 62 GyRBE (range, 54-68 GyRBE) |

56.9 m | 14% failures (WHO grade 1: 6.6%) 5-y local control 86.4% 5-y OS 88.2% 5-y grade 3 toxicity-free survival was 89.1% Acute side effects (90.6%): alopecia 65.6% (all grade 1//2), radiodermitis 47.9% (all grade 1/2) Long-term side effects (45%): optic tract 33% and pituitary (23%) Grade 3 + 10% (cataract, optic nerve edema, amaurosis fugax, brain necrosis) |

| Vlachogiannis et al., 201740 (R) |

D (44) A (84) S (42) |

170 | 1 | BoS (155) Other (15) |

GTV* CTV = GTV PTV = CTV + 5 mm CTV 12.97 cc (rage 1-64 cc) |

SSPT | 21.9 (14-46) in 3-8 fx | 24 m | 5-y PFS 93% and 10-y PFS 85% Mortality 13.5% (disease specific 1.7%) 9.4% (n = 16) treatment-related toxicity *enhancing/ CT based MRI—since 2000 |

| El Shafie et al., 201847 (R) |

D (42) A (17) S (51) |

104 (protons) 6 (carbon) | 1(102), 2(1), 3(1) | BoS | GTV (enhancing tumor) CTV = GTV + 1-2mm (grade 1) or + 5 mm (grade 2+) PTV = 3 mm GTV 28.7 cc CTV 44.5 cc PTV 68 cc |

NR | 54 GyRBE (range 50–60 GyRBE) at 1.8/2 GyRBE. | 46.8 m | 3-y PFS 100% and 5-y PFS 96.6% 5-y OS 96.2%; 6-y OS 92% (no mortality, disease related) grade 3 + acute (1 patient of mucositis and 1 patient nausea), late (1 patient fatigue and 3 patients RN) For adverse effects; Proton or carbon not specified |

| Holtzman et al., 202348 (P) |

D A |

59 (64) | 1 | All | GTV (enhancing tumor) CTV = GTV + 5 mm PTV = 3 mm GTV 7.5 cc |

PSPT | 50.4 (48.6-61.2) at 1.8/fx | Clinical 6.3 y Imaging 4.7 y |

5-y OS 87% (95% CI 74-94%). 5-y local progression 6% (95% CI 1%-14%) 5-y grade 3 + toxicity 2% (95% CI 1%-15%) 2 patients local progressed after 5-y |

| Author and year (study type) |

RT purpose | np (nles) | WHO grade | Tumor location |

Target definition and volumes (cc) | Type of PT | Prescribed dose (GyRBE) | mFU | Outcomes/AE/comments |

np, number of patients; nles, number of lesions; mFU, median follow-up; cc, cubic centimeters; mm, millimetres; PBS, pencil beam proton therapy; PSPT, Passive-scattering proton therapy; SSPT, spot scanning proton therapy; (P), Prospective; (R), retrospective; D, definitive; A, adjuvant; S, salvage (recurrence/progression); PFS, progression-free survival; ORR, Objective response rate; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; SRT, Stereotactic radiotherapy; HSRT, hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy; LC, local control; OS, overall survival; AE, adverse effects; NR, Not reported; CN, cranial nerve; WHO, World Health Organization; GTV, Gross tumor volume; CTV, Clinical target volume; PTV, Planning target volume; ON, Optic nerve; CN, Cranial nerve; BoS, Base of skull; fx, fractions.

WHO grade 2 and 3 meningiomas

Prospective data supporting the benefit of adjuvant RT after gross total resection (GTR) of a WHO grade 2 meningioma will be generated by 2 randomized trials: the recently completed ROAM/EORTC-1308 trial (completed accrual but none of the patients were treated with PT) and the ongoing NRG-BN003. Current guidelines recommend fractionated RT for WHO grade 2 and 3 meningiomas, SRS is not supported due to the lack of high-level evidence.35 Also, the current evidence supporting the use of PT in this patient subgroup is primarily retrospective with limited prospective data. For patients with WHO grade 2 meningiomas who undergo subtotal resection (STR), or relapse after surgery alone, or for newly diagnosed or recurrent WHO grade 3 meningiomas, outcomes with photon RT are modest and there may be a dose-dependent response, with a possible benefit from dose escalation.50 To this end, Chan et al. investigated the combination of photon therapy with a proton boost for primary and recurrent meningiomas in a prospective phase I/II study which included six patients treated to 68.4 (G2) and 72 GyRBE (G3) (1.8 GyRBE/fraction).51 Proton dose escalation was safe and there were no grade 3 + toxicities; local control rates were higher than historically reported.

WHO grades 2 and 3 meningiomas may also benefit from PT dose escalation when there is gross residual disease adjacent to a critical neurologic OAR, such as for skull-base tumors.52 It is important to note that the upper dose ranges for multiple retrospective PT studies were between 66.1 and 70.4 GyRBE,45,46,51,53,54 higher than with photon RT, with higher control rates and lower rates of treatment-related toxicities, although comparative studies are lacking. Two clinical trials are currently evaluating PT dose-escalation: the PANAMA trial (NCT02978677) for grades 2 and 3 meningiomas with dose escalations up to 68 GyRBE and 72 GyRBE, respectively, in the adjuvant setting after STR; and NCT02693990, a phase 1/2 study investigating IMPT dose escalation for grade 2 and 3 meningiomas after biopsy or STR. For this patient population, PT should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis in those with challenging locations, to reduce the risk of treatment-related toxicities, or when dose escalation is considered for those with high-grade tumors, recurrent, or residual disease (Table 4).

Craniopharyngioma and Pituitary Adenoma

Considering the complex anatomy in and around the sella, craniopharyngiomas and pituitary adenomas often cause a variety of symptoms, including endocrine, visual, headaches, etc. RT is a valuable component of the treatment paradigm, but traditional photon RT can be challenging to deliver given the multiple proximate OARs, raising concerns about long-term side effects, including cognitive dysfunction, visual impairment, hormonal imbalances, and secondary malignancies. Given the benign nature of these tumors and the lengthy overall disease natural history, PT is often considered.

Craniopharyngioma

Although benign, craniopharyngiomas are highly invasive, tend to recur locally, and are often challenging to treat. Given the low incidence in adults, treatment paradigms and management approaches follow pediatric guidelines. Although GTR is recommended, given the complexity of location, tumor size, and nearby OARs, a planned approach with STR and RT also results in similar levels of tumor control, intellectual functioning, and quality of life,55 and is recommended by consensus guidelines in the setting of hypothalamic infiltration.56 PT-specific studies for craniopharyngiomas have demonstrated promising local control rates (>90%) with low rates of treatment-related acute and late toxicities.57 Prospective clinical trials have not only recapitulated these results, but demonstrated superior neurocognitive preservation secondary to reduction in dose to cognitive substructures (ie, temporal lobes, hippocampus, and integral brain dose). In a phase 2 trial of 94 craniopharyngioma patients treated with PT compared with 100 patients treated with photon RT, similar tumor control rates and toxicities were observed, but significantly increased risks of decline in intelligence quotient (IQ: –1.09 points per year, P = .0070) and adaptive behavior (−1.48 points per year, P = .030) were observed in patients treated with photon RT.58 Routine weekly interfraction imaging is also recommended during a course of conventionally fractionated PT since the target volumes are prone to change and these fluctuations may translate to differences in proton dose deposition than the original treatment plan.59 Notably, the available data is predominantly based on fractionated treatments, and there is limited and heterogeneous data regarding SRS. The International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) considers SRS for patients with very small tumors (<3.5 mL) or for those more than 3 mm away from the optic chiasm, since larger tumors are associated with a high risk of optic-endocrine complications (>15%); moreover, single fraction treatments not only do not have a high level of evidence to support their recommendation but also risk brain tissue and optic nerve injuries given lack of long-term safety data in the pediatric population.60 PT is often recommended in young patients given the lengthy natural history of the disease, and location adjacent to multiple critical OARs or neurocognitive substructures (Table 4).

Pituitary adenoma

The indications for RT have been well established for both functional pituitary adenomas (FPAs; hormone-producing) after resection and/or endocrine therapy and nonfunctional adenomas (NFAs) in the definitive, adjuvant, or salvage setting.61 Photon stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is commonly used for smaller tumors. Dosimetric evaluation of PSRS has demonstrated comparable target coverage with reductions in nearby OAR doses, as well as reduction in integral brain and meningeal surface dose.49 Although standard photon RT results in excellent tumor control (90%–100%), PT may be considered as an alternative in those with residual or recurrent disease, or those with select FPAs that are historically resistant to photon RT in terms of hormone stabilization. In a series of 61 patients treated with PSRS (20 GyRBE [15–24 GyRBE] for FPA and 17 GyRBE [15–20 GyRBE] for NFA), 76 to 100% achieved an objective response in patients with FPA (based on Cushing’s disease, acromegaly, and prolactinoma or TSH‑secreting tumors) and for NFA, significant tumor volume reduction was observed.62 PSRS is not often recommended for small volume targets (reported to a median volume of approximately 3.5 cc) given the improvements in photon SRS. For NFAs, an ISRS systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated 5-year local control rates of 94% with SRS and 97% with HSRT and modest treatment-related toxicities of hypopituitarism (21%) and visual dysfunction and cranial neuropathies in 0%–7%.63 For FPAs, photon SRS has been associated with tumor control rates and rates of endocrine remission of 97% and 44% for acromegaly, 92% and 48% for Cushing disease, and 93% and 28%, for prolactinomas.64 If conventionally fractionated approaches are considered (ie, large tumors or those close to the optic pathway) and given the long-term natural history of the disease, complex anatomy with multiple critical neurologic OARs and neurocognitive substructures, or to reduce the risk of secondary malignancy, PT can be considered for this patient subgroup (Table 4).65

Vestibular Schwannoma

The natural history of most vestibular schwannomas is characterized by a slow growth rate; however, they can still cause significant morbidity due to their size and location and can lead to progressive hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, and facial numbness.

For medically inoperable patients, those who present with surgically unresectable tumors, or patients who undergo STR, and increasingly, simply by patient choice, definitive or adjuvant RT is often recommended. The ISRS guidelines strongly recommend the use of SRS (11–14 Gy, single fraction) for newly diagnosed vestibular schwannomas Koos grades I-III (I, intracanalicular; II, minimal extension into the cerebellopontine angle, <2 cm; tumor occupying the cerebellopontine angle but not displacing the cerebellar trunk, <3 cm) given the long-term outcomes of 90%–99% tumor control and 41%–79% hearing preservation. It is important to note that surgery alone can also be considered for such cases, depending on the hearing status and medical comorbidities of the patient. For patients with moderate volume disease (Koos grades I-III), hypofractionated schedules or conventionally fractionated treatments can also be used.66 PSRS studies have shown promising results in terms of tumor control, similar to photon SRS. In a series of 68 patients with a median tumor volume of 2.5 cc treated with 12 GyRBE PSRS, with a median follow-up of 44 months, the local control rates at 2 and 5 years were 94% and 84%, respectively.67 It is important to note that although the toxicity was considered acceptable in the publication, with facial hypesthesia in 4.7%, intermittent facial paresthesia in 9.4%, and persistent facial partial transitory weakness in 9.4%, this is higher than modern photon SRS results. Another series compared 158 patients treated with conventional photon stereotactic RT (stereotactic radiation therapy, 54 Gy in 1.8 Gy/fraction schedule) to PSRS (median dose 12 GyRBE, single fraction, isodose line 70%), and showed similar local control rates at 3 and 5 years (100% and 98% for stereotactic radiation therapy, and 97% for both in PSRS) and similar facial neuropathy rates.68 Given the improvements in photon SRS technologies, limitations with current PSRS techniques, and the historically higher rates of treatment-related toxicities compared to photon series, PSRS is not often recommended for such cases. However, in the setting of large-volume disease where upfront SRS or hypofractionated treatment is contraindicated, a conventionally fractionated approach with PT should be considered given the long-term natural history of the disease and superior dosimetry and critical OAR sparing to reduce long-term treatment-related toxicities or risk of secondary malignancies (Table 4).

Primary Extra-Axial Skull-Base Tumors

Chordoma/Chondrosarcoma

Intracranial chordomas and chondrosarcomas are uncommon tumors that typically arise in the base of skull. The optimal definitive treatment is GTR and adjuvant high-dose RT, but this is challenging given the location and anatomic complexity. Photon RT is less effective against these tumors because of dose limitations. Treatment with carbon-ion therapy or with high-dose PT yields higher local control rates for longer durations.69 A recent meta-analysis which included 478 patients from 7 PT studies demonstrated 5- and 7-year local control and overall survival rates of 78% and 68%, and 85% and 68%, respectively, and modest toxicities.70 PT permits adequate coverage of the target volumes with the high doses needed for disease control,71,72 and minimizes dose to surrounding OARs (ie, optic nerves, optic chiasm, and temporal lobes), thereby reducing toxicities.73 PT outcomes appear superior to those reported for photon RT series, even using modern stereotactic techniques and in population-based studies,74 such as a large PT series of 863 patients with chondrosarcomas and 715 with chordomas, and have been associated with improved OS.75

Chordoma

Chordomas are rare aggressive tumors derived from notochordal remnants, commonly arising from the base of skull (clivus), spine, and sacrum. Upfront resection, when feasible, is the standard of care, but achieving a GTR is challenging.76,77 Adjuvant RT remains critical since the recurrence rate is approximately 70% with surgery alone.76

Prior studies with either adjuvant or definitive photon-based RT, generally using 40–50 Gy, were associated with high rates of disease progression and poor survival. Even modern series with median prescription doses of 66 Gy are associated with modest tumor control rates.74 Multiple PT series support the use of an even higher prescription dose (70–78 Gy), especially as a majority of failures occur at a junction with a critical OAR (Table 3).71,72,81,84,89,95 This dose–response slope for chordomas is widely recognized and current consensus recommendations from the European Society of Medical Oncology specify 70 Gy after GTR and 74 Gy after STR, which are difficult to safely deliver with photon RT.96 Recently, the proton collaborative group REG001-09 trial published the results of 100 patients treated with PT for chordomas (61% intracranial, base of skull) with a median proton RT dose of 74 GyRBE and showed that PT provides excellent efficacy, with low rates of treatment failure, limited CNS necrosis rates (<1%), and no grade 3 + late toxicities.97 PBS PT has demonstrated comparable, early outcomes, and likely affords better dosimetric sparing.98 Therefore, patients with skull-base chordomas should be evaluated for PT to facilitate dose-escalation, improve target volume coverage, and reduce treatment-related toxicities (Table 4).

Table 3.

Selected Series of Proton Therapy for Patients With Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas

| Author and year (Study Type) |

RT purpose | n | Tumor | Targets | Target volumes (cc) | PT | Prescriber Dose (GyRBE) |

mFU | Outcomes | AE/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hug et al., 199978 (P) |

A, D | 25 −22 (p) −3 (p + x) |

Ch, ChS | GTV (CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + 5mm; |

≤15 cc: 32%, >15 to ≤ 25 cc: 28% >25 cc: 40% |

PSPT | mean 69.3 (64.8–72.0); [1.8/fx] |

33.2 m (7–75) | 3- and 5-y LC: 94%, 75% 3- and 5-y OS: 100%, 100% |

G3± toxicity (7%):

1 temporal lobe damage (on MRI) 2 hearing loss 1 focal seizure 1 bilateral vision loss G1-2 toxicity in 8 pts(14%): 4 partial pituitary insufficiency 4 unilateral hearing deficit |

|

Rosenberg et al., 199979 (P) |

A, S | 200 (x + p) |

ChS | GTV (CT and MR) | NR | PSPT | 64.2–79.6; [1.8–1.9/fx] |

65.3 m (2.1-222) | 5- and 10-y LC: 99%, 98% 5- and 10-y OS: 99%, 99% |

NR |

|

Noël et al., 2003 (P)80 |

NR | 67 (x + p) |

Ch (49) ChS (18) |

GTV (CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + 5–10 mm, PTV = CTV + 3 mm |

median GTV 20 cc (1–124) | PSPT | 67 (60–70); [1.8–2/fx] mean dose of photons: 45 Gy |

29 m (4–71) | Ch: 3-y LC, DSS, OS: 71%, 88%, 62% ChS: 3-y LC, DSS, OS: 85%, 75%, 91% |

Overall late toxicity 49% G3 oculomotor impairment: 2 G4 bilateral loss of vision: 1 G2 hearing loss: 18% G2 pituitary deterioration: 24% Temporal lobe dysfunction: 1 |

|

Igaki et al., 200481 (R) |

A (6), D (6), S (1) | 13 | Ch | GTV (CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + 5–10 mm |

median 25.7 cc (3.3-88.4) | NR | 72.0 (63.0–95) | 69.3 m (14.6–123.4) | 5-y LC, CS (Cause-specific), OS, DFS 46%, 72.2%, 66.7% and 42.2% | Acute toxicities: headache: 3 (G1 in 2; G2 in 1) Nausea G1 In 1 Late toxicities: Brain necrosis G4 in 1; G5 in 1 Oral ulceration (G4) 1 patient. LC higher for those with < 30 cc |

|

Weber et al., 200582 Ares et al., 200972 (P) |

A, S | 64 | Ch (42) ChS (22) |

GTV (CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + suspected microscopic spread PTV = CTV + 5 mm |

≤25 cc 24 (Ch), 15 (ChS) > 25 cc: 18 (Ch) 7 (ChS) |

Spot-scanning | median 73 (Ch) 68.4 (ChS) [1.8–2/fx] |

38 m (14–92) | Ch: 5-y LC, DSS, OS: 81%, 81%, 62% ChS: 5-y LC, DSS, OS: 94%, 100%, 91% |

Unilateral optic neuropathy: 1 (G3), 1 (G4) G3 CNS necrosis: 1 5-y freedom from high-grade toxicity: 94% |

|

Fuji et al., 201183 (R) |

A | 16 | Ch (8) ChS (8) |

GTV (CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + 5–8 mm |

median GTV 40 cc (7–546) | NR | 63 (50–70) [1.8/fx] |

42 m (9–80) | Ch: 3-y LC, OS: 100%, 100% ChS: 3-y LC, OS: 86%, 100% |

No G3 + reported |

|

Deraniyagala et al., 201484 (R) |

A, D | 33 | Ch | NR | NR | NR | 74 (70–79) [1.8–2/fx] |

21 m (3–58) | 2-y LC, OS: 86%, 92% | G2: 18% (unilateral hearing loss partially corrected with a hearing aid). |

|

Grosshans et al., 201485 (P) |

A, D, S | 15 | Ch (10) ChS (5) |

GTV = residual disease 2 CTVs in 13 patients: CTV1 = GTV + 5–8 mm CTV2 = CTV + as judged by the treating physician |

15-26.2 cc | IMPT (SFO in 10/MFO in 5) 3 to 4 beams used |

Ch 69.8 (68–70) ChS 68.4 (66–70) [1.8–2/fx] |

27 m (13–42) | NR | Acute toxicities: fatigue: 3 (G1 in 8; G2 in 2) Nausea G1 in 6 and G2 in 2 No G3+ |

|

Hayashi et al., 201686 (R) |

A, D | 19 | Ch | GTV (CT and MRI) CTV = GTV + 5–10 mm PTV = CTV + 5 mm |

median 19 cc (1.7-62.9 cc) | Double scattering method | 9 cases: 77.44 10 cases: 78.4 [1.2–1.4/fx, bid] |

61.7 m (31.5–115.4) | All patients: 5-y LC, DSS, OS: 75%, 94%, 83.2% 10 patients receiving 78.4 GyRBE: 5-y LC, DSS, OS: 100%, 100%, 88.9% |

1 bilateral temporal lobe RN 2 transient neurological symptoms |

|

Weber et al., 201687 (P) |

A | 222 | Ch (151) ChS (71) |

NR | median GTV 37.5 ± 29.1 | SFUD/IMPT | Ch 74 GyRBE, ChS 70 GyRBE mean 72.5 ± 2.2 [1.8-2/fx] |

50 m (4–176) |

Ch: estimated 7-y LC, MFS (mets), OS: 70.9%; CI95% 61.5–81.8; 91.6% (95%CI: 91.6–98.6), 81.7% (95%CI: 74.7–89.5), ChS: estimated 7-y LC, MFS (mets), OS 93.6%; 95%CI 87.8–99.9 |

7-y high grade toxicity-free survival was 87.2 (95%CI 82.4–92.3). |

|

Mattke et al., 201888 (R) |

A,D,S | 22 (protons) 79 (carbon ion) |

ChS | GTV = defined MRI CTV1 = GTV + preOp extent CTV2 = GTV + 1–2 mm PTV1/PTV2 = CTV 3 mm |

Median boost (CTV) 38.2 cc | NR | 70 [2/fx] | 30.7 m |

For protons:

1-y, 2-y, 4-y LC 100% 1-y, 2-y, 4-y OS 100% |

No grade > 3 toxicities |

|

Hottinger et al., 202089 (P) |

A, D | 142 | NR | NR | median GTV 26.3 cc (0–130.4) | PBS-PT | 74.0 (72.6–80.0) [1.8–2.5/fx] |

52 m (3–152) | 5-y LC, OS 75%, 83% | NR “Sekhar Grading System for Cranial Chordomas” (SGSCC) o stratify by risk |

|

Iannalfi et al., 202090 (P) |

A | 70 (protons) 65 (carbon ion) |

Ch | GTV = MRI T1-Gd+ CTV-HR = GTV + 3-5 mm CTV-LoR = CTV-HR + 5 mm |

Median GTV (protons): 3.5 cc | PBS-PT | Median 74 (72–74) | 49 m (6-87) |

For protons:

8 (11%) local failures 5-y LC 84% 5-y OS 83% |

High-grade toxicity (grade 3+) 12% (ear 9; endocrine 1; eye 4; CNS 3) No grade 5 |

|

Riva et al., 202191 (R) |

A | 32 (protons) 16 (carbon) |

ChS | GTV = MRI T2 weighted and post contrast T1. CTV-HR = GTV + 3–5 mm CTV-LoR = preoperative + CTV-HR |

NR | NR | 50 (LR) + 20 (HR) [2/fx] | 38 m | 3-y LC 100% |

Protons:

2 patients grade 3 late toxicity No grade 3 + brain injury |

|

Gordon et al, 202192 (R) |

A | 31 | Ch (23) ChS (8) |

GTV = residual or tumor bed in R1 (CT and MRI) CTV = preoperative MRI + GTV + 10 mm |

median GTV 25.6 cc (4.2–115.6) | IMPT (MFO) | 70 (60–74) [2/fx] |

21 m (4–52) | 1-y LC 100% 2-y LC 93.7% 3-y LC 85.3% 1-y and 2-y OS 100% 3-y OS 66.3% |

2 grade 3 + toxicities (6.4%): 1 grade 3 myelitis and 1 grade 5 brain stem injury |

|

Mattke et al., 202293 (R) |

A,D | 36 (protons) 111 (carbon ion) |

Ch | GTV = defined MRI CTV1 = GTV + preOp extent CTV2 = GTV + 1–2 mm PTV1/PTV2 = CTV 3 mm |

Median boost (CTV) 38.3 cc | NR | 50 + 24 [2/fx] | 36.5 m (protons) |

Protons: 1-y LC/OS 97%/100% 3-y LC/OS 80%/92% 5-y LC/OS 61%/92% |

13% G3 No grade 4+ |

|

Ioakeim-Ioannidou et al., 202394 (P) |

A | 204 (p; x + p) |

Ch | NR | NR | NR | median 76.7 GyRBE (range, 59.3-83.3) | 10 y (IQ 5–16 y) | Median OS, PFS: 26 and 25 y 5-, 10-, and 20-year OS 84%, 74%, 78% 5-, 10-, and 20-year PFS 69%, and 64% and 64% |

Acute toxicity: 80% mild/moderate Late toxicity: 12% Secondary malignancies: 4 (2%) |

n ,number of patients; mFU, median follow-up; p, protons; x, photons; cc, cubic centimeters; mm, millimeters; PSPT, Passive-scattering proton therapy; (P), Prospective; (R), retrospective; D, definitive; A, adjuvant; S, salvage (recurrence/progression); Ch, chordoma; ChS, Chondrosarcoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computerized tomography; PFS, progression-free survival; ORR, Objective response rate; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; LC, local control;OS, overall survival; AE, adverse effects; NR, Not reported; CN, cranial nerve; WHO, World Health Organization; fx, fraction; GTV, Gross tumor volume; CTV, Clinical target volume; HR, high risk; LoR, lower risk; PTV, Planning target volume; ON, Optic nerve; IMRT, Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy.

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcomas originate from endochondral bones and can occur anywhere in the skeletal system. When occurring intracranially, they commonly arise from the temporo-occipital junction, parasellar area, sphenoethmoidal complex, and clivus. Chondrosarcoma patients are often included in mixed PT series with chordoma patients given similar anatomy, location, and treatment paradigms (Table 3). In these series, chondrosarcomas are treated to slightly lower doses (~ 68 GyRBE) with better local control rates than observed with chordomas. The 3- and 5-year local control rates for chordomas (42 patients, 68.4 GyRBE) and chondrosarcomas (22 patients, 73.5 GyRBE) treated with PT were 87% and 94%, and 81% and 94%, respectively.72 Given the importance of adequate coverage of the target to reduce the risk of treatment failure and of dose-escalation, especially in the setting of residual disease,75,88 and the proximity to critical OARs with tolerance levels less than the prescription doses required in the adjuvant or definitive setting for chondrosarcomas, PT requires consideration (Table 4).

Secondary Malignancies of the Central Nervous System

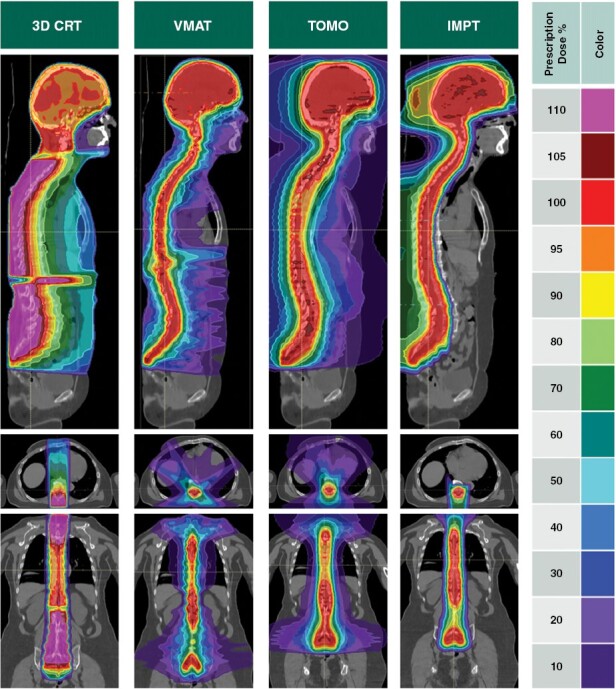

LMD is associated with a high incidence of neurological symptoms and occurs in up to 37% of patients (co-occurring with brain metastasis in 2%–12% of patients). It is generally associated with poor prognosis, with an expected survival of one month without treatment, and up to 4–6 months with standard therapies, such as involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT), including whole brain irradiation or focal spine RT. Although these treatments can improve clinical symptoms, they are not able to completely eradicate the disease from progressing throughout the leptomeningeal space. Photon CSI series for LMD are associated with significant risk of myelosuppression and frequent inability to complete the treatment course.113 PT is dosimetrically superior to photon RT when irradiating the craniospinal axis due to rapid dosimetric fall-off and comparative series have demonstrated lower rates of weight loss, less bone marrow suppression, reduced incidence of grade 2 + nausea and vomiting, and reduced grade 3 + esophagitis with proton CSI compared to photon CSI (Figure 2).106

Figure 2.

Craniospinal irradiation isodose dose distributions for a variety of radiotherapy techniques including 3D conformal radiotherapy, volumetrically modulated radiation therapy, tomotherapy, and intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) demonstrating significantly reduced vertebral body and extracranial organ doses with IMPT compared to all other photon modalities. Footnote:3D CRT, Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy. VMAT, Volumetric modulated arc therapy. TOMO, Tomotherapy. IMPT, Intensity-modulated proton therapy.

Based on the safety signal from a phase 1B trial, a phase 2 randomized trial compared proton CSI with photon IFRT in patients with LMD from lung and breast cancer.107 With 9.3 months median follow-up on 63 patients, the CNS progression rates were 28.6% and 76.2% for proton CSI and IFRT, respectively, with a median CNS PFS of 7.5 months versus 2.3 months, in favor of PT (P < .0001).108 Overall survival was improved with PT, median OS of 9.9 versus 6 months (P < .029). Encouraging outcomes were also observed in an exploratory cohort of patients with other solid tumor malignancies treated with proton CSI.

Given the current randomized data, we would consider proton CSI for patients with good risk LMD (ie, Karnofsky performance status ≥ 60 and eligible to complete a course of RT and subsequently receive systemic therapy) (Table 4).

Re-irradiation

Re-irradiation for patients with intracranial tumors presents a challenging scenario that requires a comprehensive evaluation of patients-specific factors (ie, age, performance status, neurologic symptomatology, etc.), disease-specific factors (ie, tumor extent, histology, molecular profile), and treatment-related factors (i.e. alternative treatments such as surgery or systemic therapy, time from last irradiation, dosimetry of the original plan and intended area and dose of re-irradiation).114 Consensus guidelines regarding the role of re-irradiation do not exist for intracranial tumors and re-irradiation is infrequently used due to the limited available data and the increased risk for severe treatment-related toxicities, especially when large target volumes are involved or when critical OAR tolerances could be exceeded. Multiple published retrospective series support the role of PT in this setting. For example, data from the proton collaborative group on 45 patients with recurrent GBM (median initial dose of 60 Gy) re-irradiated with PT at a median interval of 20 months from the initial course to a median dose of 46.2 GyRBE, demonstrated median PFS and OS of 13.9 and 14.2 months, with only one patient experiencing an acute grade 3 toxicity, four patients experiencing late grade 3 toxicities, and no grade ≥ 4 toxicities were reported.110 In a retrospective series of 42 patients with WHO grade 1–3 meningioma re-treated with particle therapy (8 PT) to a median dose of 51 GyRBE in 19 fractions, 1- and 2-year PFS rates were 71% and 57%, with no grade 4 + toxicities.111 In another series, twenty pediatric patients who had received multiple (2–7) prior RT courses were re-treated with PT to a median dose of 50.4 GyRBE. With 37.8 months median follow-up, the 3-year OS and PFS rates were 78.6% and 28.1%.112 Given the limited and heterogeneous nature of these series, and yet surprisingly positive results for heavily pretreated patients, and potential integration of novel forms of particle therapy delivery, PT could be routinely incorporated into the treatment decision-making discussion for any patient with an intracranial tumor considered for re-irradiation.

Conclusions

Based on the available data, and recognizing the paucity of level 1 evidence, we provide our recommendations for the use of PT in tabular fashion in Table 4. We recognize the urgent need to generate high-level evidence through prospective trials and data collection and until this is available, consider therapeutic individualized decision making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Nicole C. McAllister, CMD.; Kamaryn Gose, BSMI, RT (R)(T)(CT); and Zachary D. Fellows, CMD., who generously volunteered their time to create dosimetric examples for this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rupesh Kotecha, Department of Radiation Oncology, Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Radiation Oncology, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Translational Medicine, Hebert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA.

Alonso La Rosa, Department of Radiation Oncology, Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, Florida, USA.

Minesh P Mehta, Department of Radiation Oncology, Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, Florida, USA; Department of Radiation Oncology, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Supplement sponsorship

This article appears as part of the supplement “Pushing the Boundaries of Radiation Technology for the Central Nervous System,” sponsored by Varian Medical Systems.

Conflicts of interest statement

R.K.: Honoraria from Accuray Inc., Elekta AB, ViewRay Inc., Novocure Inc., Elsevier Inc., Brainlab, Kazia Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, and Ion Beam Applications and institutional research funding from Medtronic Inc., Blue Earth Diagnostics Ltd., Novocure Inc., GT Medical Technologies, AstraZeneca, Exelixis, ViewRay Inc., Brainlab, Cantex Pharmaceuticals, Kazia Therapeutics, and Ion Beam Applications. A.L.R.: Travel/reimbursement by GT Medical Technologies. M.P.M.: Consulting Fees from Karyopharm, Sapience, Zap, Mevion, Xoft; Kazia Therapeutics; BOD Oncoceutics; Stock in Chimerix

References

- 1. Mohan R. A review of proton therapy – Current status and future directions. Precis Radiat Oncol. 2022;6(2):164–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lomax AJ. Charged particle therapy: The physics of interaction. Cancer J. 2009;15(4):285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dutz A, Agolli L, Bütof R, et al. Neurocognitive function and quality of life after proton beam therapy for brain tumour patients. Radiother Oncol. 2020;143:108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jalali R, Gupta T, Goda JS, et al. Efficacy of stereotactic conformal radiotherapy vs conventional radiotherapy on benign and low-grade brain tumors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1368–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laack NN, Brown PD, Ivnik RJ, et al. ; North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Cognitive function after radiotherapy for supratentorial low-grade glioma: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(4):1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohan R, Liu AY, Brown PD, et al. Proton therapy reduces the likelihood of high-grade radiation-induced lymphopenia in glioblastoma patients: Phase II randomized study of protons vs photons. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(2):284–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miralbell R, Lomax A, Cella L, Schneider U.. Potential reduction of the incidence of radiation-induced second cancers by using proton beams in the treatment of pediatric tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(3):824–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Particle therapy facilities in clinical operation. https://www.ptcog.site/index.php/facilities-in-operation-public. Accessed July 24, 2023.

- 9. Lehrer E, Prabhu A, Sindhu K, et al. Proton and heavy particle intracranial radiosurgery. Biomedicines. 2021;9(1):1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gupta A, Khan AJ, Goyal S, et al. Insurance approval for proton beam therapy and its impact on delays in treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104(4):714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang M, Xu F, Ni W, et al. Survival impact of delaying postoperative chemoradiotherapy in newly-diagnosed glioblastoma patients. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9(9):5450–5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tonse R, Sabouri P, Mehta MP, Kotecha R.. Intracranial tumors. Princ Pract Particle Ther. 2022;1:177–199. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frame CM, Chen Y, Gagnon J, et al. Proton induced DNA double strand breaks at the Bragg peak: Evidence of enhanced LET effect. Front Oncol. 2022;12:930393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sørensen BS, Bassler N, Nielsen S, et al. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) and distal edge effects of proton radiation on early damage in vivo. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(11):1387–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrabi SB, von Nettelbladt B, Gudden C, et al. Radiation induced contrast enhancement after proton beam therapy in patients with low grade glioma - How safe are protons? Radiother Oncol. 2022;167:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haas-Kogan D, Indelicato D, Paganetti H, et al. National cancer institute workshop on proton therapy for children: Considerations regarding brainstem injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(1):152–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsujii H, Tsuji H, Inada T, et al. Clinical results of fractionated proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25(1):49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hauswald H, Rieken S, Ecker S, et al. First experiences in treatment of low-grade glioma grade I and II with proton therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7(1):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greenberger BA, Pulsifer MB, Ebb DH, et al. Clinical outcomes and late endocrine, neurocognitive, and visual profiles of proton radiation for pediatric low-grade gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89(5):1060–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shih HA, Sherman JC, Nachtigall LB, et al. Proton therapy for low-grade gliomas: Results from a prospective trial. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1712–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sherman JC, Colvin MK, Mancuso SM, et al. Neurocognitive effects of proton radiation therapy in adults with low-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2016;126(1):157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilkinson B, Morgan H, Gondi V, et al. Low levels of acute toxicity associated with proton therapy for low-grade glioma: A proton collaborative group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(2S):E135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tabrizi S, Yeap BY, Sherman JC, et al. Long-term outcomes and late adverse effects of a prospective study on proton radiotherapy for patients with low-grade glioma. Radiother Oncol. 2019;137:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brown PD, Chung C, Liu DD, et al. A prospective phase II randomized trial of proton radiotherapy vs intensity-modulated radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1337–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Douw L, Klein M, Fagel SS, et al. Cognitive and radiological effects of radiotherapy in patients with low-grade glioma: Long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(9):810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klein M, Drijver AJ, van den Bent MJ, et al. Memory in low-grade glioma patients treated with radiotherapy or temozolomide: A correlative analysis of EORTC study 22033-26033. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(5):803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flechl B, Konrath L, Lütgendorf-Caucig C, et al. Preservation of neurocognition after proton beam radiation therapy for intracranial tumors: First results from REGI-MA-002015. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;115(5):1102–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heggebø LC, Borgen IMH, Rylander H, et al. Investigating survival, quality of life and cognition in PROton versus photon therapy for IDH-mutated diffuse grade 2 and 3 GLIOmas (PRO-GLIO): A randomised controlled trial in Norway and Sweden. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e070071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gondi V, Hermann BP, Mehta MP, Tomé WA.. Hippocampal dosimetry predicts neurocognitive function impairment after fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for benign or low-grade adult brain tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(2):348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kotecha R, Hall MD.. Impact of radiotherapy dosimetric parameters on neurocognitive function in brain tumor patients. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(11):1559–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fitzek MM, Thornton AF, Rabinov JD, et al. Accelerated fractionated proton/photon irradiation to 90 cobalt gray equivalent for glioblastoma multiforme: results of a phase II prospective trial. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(2):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adeberg S, Bernhardt D, Harrabi SB, et al. Sequential proton boost after standard chemoradiation for high-grade glioma. Radiother Oncol. 2017;125(2):266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Combs SE, Kieser M, Rieken S, et al. Randomized phase II study evaluating a carbon ion boost applied after combined radiochemotherapy with temozolomide versus a proton boost after radiochemotherapy with temozolomide in patients with primary glioblastoma: the CLEOPATRA trial. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang J, Mehta M.. Can proton therapy reduce radiation-related lymphopenia in glioblastoma? Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(2):179–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goldbrunner R, Stavrinou P, Jenkinson MD, et al. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and management of meningiomas. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(11):1821–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marchetti M, Sahgal A, De Salles AAF, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial noncavernous sinus benign meningioma: International stereotactic radiosurgery society systematic review, meta-analysis and practice guideline. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(5):879–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee CC, Trifiletti DM, Sahgal A, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for benign (World Health Organization Grade I) Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas-International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (ISRS) practice guideline: A systematic review. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(6):1128–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halasz L, Bussière M, Dennis E, et al. Proton stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of benign meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(5):1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vernimmen F, Harris J, Wilson J, et al. Stereotactic proton beam therapy of skull base meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49(1):99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vlachogiannis P, Gudjonsson O, Montelius A, et al. Hypofractionated high-energy proton-beam irradiation is an alternative treatment for WHO grade I meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017;159(12):2391–2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gudjonsson O, Blomquist E, Nyberg G, et al. Stereotactic irradiation of skull base meningiomas with high energy protons. Acta Neurochir. 1999;141(9):933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weber DC, Lomax AJ, Rutz HP, et al. ; Swiss Proton Users Group. Spot-scanning proton radiation therapy for recurrent, residual or untreated intracranial meningiomas. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71(3):251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weber DC, Schneider R, Goitein G, et al. Spot scanning-based proton therapy for intracranial meningioma: Long-term results from the Paul Scherrer Institute. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(3):865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Slater JD, Loredo LN, Chung A, et al. Fractionated proton radiotherapy for benign cavernous sinus meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):e633–e637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McDonald MW, Plankenhorn DA, McMullen KP, et al. Proton therapy for atypical meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2015;123(1):123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murray FR, Snider JW, Bolsi A, et al. Long-Term clinical outcomes of pencil beam scanning proton therapy for benign and non-benign intracranial meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99(5):1190–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. El Shafie RA, Czech M, Kessel KA, et al. Clinical outcome after particle therapy for meningiomas of the skull base: Toxicity and local control in patients treated with active rasterscanning. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Holtzman AL, Glassman GE, Dagan R, et al. Long-term outcomes of fractionated proton beam therapy for benign or radiographic intracranial meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2023;161(3):481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sud S, Botticello T, Niemierko A, et al. Dosimetric comparison of proton versus photon radiosurgery for treatment of pituitary adenoma. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2021;6(6):100806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weber DC, Ares C, Villa S, et al. Adjuvant postoperative high-dose radiotherapy for atypical and malignant meningioma: A phase-II parallel non-randomized and observation study (EORTC 22042-26042). Radiother Oncol. 2018;128(2):260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chan AW, Bernstein KD, Adams JA, Parambi RJ, Loeffler JS.. Dose escalation with proton radiation therapy for high-grade meningiomas. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2012;11(6):607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kotecha R, Mehta MP.. Modern meningioma methods: Molecular diagnostics and high dose protons. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;115(3):556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boskos C, Feuvret L, Noel G, et al. Combined proton and photon conformal radiotherapy for intracranial atypical and malignant meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(2):399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hug EB, Devries A, Thornton AF, et al. Management of atypical and malignant meningiomas: role of high-dose, 3D-conformal radiation therapy. J Neurooncol. 2000;48(2):151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aldave G, Okcu MF, Chintagumpala M, et al. Comparison of neurocognitive and quality-of-life outcomes in pediatric craniopharyngioma patients treated with partial resection and radiotherapy versus gross-total resection only. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2023;1:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cossu G, Jouanneau E, Cavallo LM, et al. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in adult patients: A systematic review and consensus statement on behalf of the EANS skull base section. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162(5):1159–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Luu QT, Loredo LN, Archambeau JO, et al. Fractionated proton radiation treatment for pediatric craniopharyngioma: preliminary report. Cancer J. 2006;12(2):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Merchant TE, Hoehn ME, Khan RB, et al. Proton therapy and limited surgery for paediatric and adolescent patients with craniopharyngioma (RT2CR): A single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(5):523–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Winkfield KM, Linsenmeier C, Yock TI, et al. Surveillance of craniopharyngioma cyst growth in children treated with proton radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(3):716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Amayiri N, Spitaels A, Zaghloul M, et al. SIOP PODC-adapted treatment guidelines for craniopharyngioma in low- and middle-income settings. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;70(11):e28493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Loeffler JS, Shih HA.. Radiation therapy in the management of pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1992–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Petit J, Cohen J, Yock T, et al. Proton radiosurgery in the management of functioning and non-functioning pituitary adenomas: A 10-year experience at the massachusetts general hospital. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(1):S312. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kotecha R, Sahgal A, Rubens M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for non-functioning pituitary adenomas: Meta-analysis and International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society practice opinion. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(3):318–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mathieu D, Kotecha R, Sahgal A, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for secretory pituitary adenomas: Systematic review and International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society practice recommendations. J Neurosurg. 2022;136(3):801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wattson DA, Tanguturi SK, Spiegel DY, et al. Outcomes of proton therapy for patients with functional pituitary adenomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(3):532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tsao MN, Sahgal A, Xu W, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (ISRS) Practice Guideline. J Radiosurg SBRT. 2017;5(1):5–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Harsh GR, Thornton AF, Chapman PH, et al. Proton beam stereotactic radiosurgery of vestibular schwannomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(1):35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chan AW, Barker FGI, Lopes VV, Martuza RL, Loeffler JS.. 1119: Comparison of fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy with proton radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: A risk-stratified analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(3):S198–S199. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mizoe JE. Review of carbon ion radiotherapy for skull base tumors (especially chordomas). Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21(4):356–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nie M, Chen L, Zhang J, Qiu X.. Pure proton therapy for skull base chordomas and chondrosarcomas: A systematic review of clinical experience. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1016857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Noel G, Feuvret L, Calugaru V, et al. Chordomas of the base of the skull and upper cervical spine. One hundred patients irradiated by a 3D conformal technique combining photon and proton beams. Acta Oncol. 2005;44(7):700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]