Keywords: alveolar dead space, hyperventilation, intrapulmonary shunt, post-COVID-19, ventilation perfusion mismatch

Abstract

Increased intrapulmonary shunt (QS/Qt) and alveolar dead space (VD/VT) are present in early recovery from 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). We hypothesized patients recovering from severe critical acute illness (NIH category 3–5) would have greater and longer lasting increased QS/Qt and VD/VT than patients with mild-moderate acute illness (NIH 1–2). Fifty-nine unvaccinated patients (33 males, aged 52 [38–61] yr, body mass index [BMI] 28.8 [25.3–33.6] kg/m2; median [IQR], 44 previous mild-moderate COVID-19, and 15 severe-critical disease) were studied 15–403 days postacute severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Breathing ambient air, steady-state mean alveolar Pco2, and Po2 were recorded simultaneously with arterial Po2/Pco2 yielding aAPco2, AaPo2, and from these, QS/Qt%, VD/VT%, and relative alveolar ventilation (40 mmHg/, VArel) were calculated. Median was 39.4 [35.6–41.1] mmHg, 92.3 [87.1–98.2] mmHg; 32.8 [28.6–35.3] mmHg, 112.9 [109.4–117.0] mmHg, AaPo2 18.8 [12.6–26.8] mmHg, aAPco2 5.9 [4.3–8.0] mmHg, QS/Qt 4.3 [2.1–5.9] %, and VD/VT16.6 [12.6–24.4]%. Only 14% of patients had normal QS/Qt and VD/VT; 1% increased QS/Qt but normal VD/VT; 49% normal QS/Qt and elevated VD/VT; 36% both abnormal QS/Qt and VD/VT. Previous severe critical COVID-19 predicted increased QS/Qt (2.69 [0.82–4.57]% per category severity [95% CI], P < 0.01), but not VD/VT. Increasing age weakly predicted increased VD/VT (1.6 [0.1–3.2]% per decade, P < 0.04). Time since infection, BMI, and comorbidities were not predictors (all P > 0.11). VArel was increased in most patients. In our population, recovery from COVID-19 was associated with increased QS/Qt in 37% of patients, increased VD/VT in 86%, and increased alveolar ventilation up to ∼13 mo postinfection. NIH severity predicted QS/Qt but not elevated VD/VT. Increased VD/VT suggests pulmonary microvascular pathology persists post-COVID-19 in most patients.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Using novel methodology quantifying intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space in COVID-19 patients up to 403 days after acute illness, 37% had increased intrapulmonary shunt and 86% had elevated alveolar dead space likely due to independent pathology. Elevated shunt was partially related to severe acute illness, and increased alveolar dead space was weakly related to increasing age. Ventilation was increased in the majority of patients regardless of previous disease severity. These results demonstrate persisting gas exchange abnormalities after recovery.

INTRODUCTION

2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS CoV-2) virus (1). Acute severe COVID-19 is characterized by acute pneumonitis, pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, and microemboli leading to arterial hypoxemia associated with increased intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space (2, 3).

Longer-term respiratory sequelae, including persistent dyspnea, impaired pulmonary function, and abnormal radiological imaging, are reported in 20%–30% of patients following recovery from acute SARS CoV-2 infection (4, 5). Post-COVID-19, some patients presenting with unexplained persistent dyspnea are reported to be hyperventilating based on questionnaire, arterial hypocapnia, and cardiopulmonary exercise response (6). A recent meta-analysis (7) found that ∼45% of post-COVID-19 patients have radiological evidence of pulmonary fibrosis. Resultant effects on pulmonary gas exchange remain to be established, although some recent MRI studies using hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI (8, 9) demonstrate abnormal transfer of Xe gas from the tissue or the parenchyma even in the presence of near normal lung imaging. This may be due to regional decreases in perfusion leading to an increase in alveolar dead space.

Using a novel technique, based on the measurement of exhaled oxygen and carbon dioxide combined with arterial blood gas analysis (10), we recently reported impaired pulmonary gas exchange [based on multiple inert gas elimination technique values (MIGET) where intrapulmonary shunt exceeding the 95% upper confidence limit of 5% in normal subjects and increased alveolar dead space exceeding the 95% upper confidence limit of 10% in normal subjects (11)] in 30 patients studied during the early stages of mild-moderate acute COVID-19 and then, in a subgroup (n = 17), of these patients studied at up to 72 days postacute infection (3). Intrapulmonary shunt was defined as an alveolar ventilation/perfusion ratio (V̇a/Q̇ of 0, also encompassing regions of very low V̇a/Q̇, and alveolar dead space was defined as a V̇a/Q̇ of infinity, also encompassing regions of very high V̇a/Q̇.

For most patients, both shunt and alveolar dead space were abnormally high at the time of the acute study and reduced at the time of the follow-up study; however, shunt at follow-up remained marginally above normal for two patients, while dead space was abnormal for five patients (i.e., ∼40% of this small cohort had persistent functional pulmonary gas exchange abnormality). Whether these patients would go on to recover in the longer term, or if there is more permanent lung damage (e.g., fibrosis) sufficient to affect gas exchange, is not known. Nor is it understood why gas exchange impairment persists into the post-COVID-19 recovery period for some patients and not others.

In addition, the prevalence, level, and underlying cause of reported hyperventilation in the post-COVID-19 population are not clear. In the acute phase of the disease, we have previously shown that 50% of these patients had alveolar ventilation greater than what is required for normocapnia (relative alveolar ventilation), and also, perhaps more importantly greater than expected for the level of hypoxemia (12). Whether this finding persists post-COVID-19 is unknown.

In this study, we hypothesized that post-COVID-19 patients with a history of more severe acute illness would have greater and longer lasting shunt and alveolar dead space values during recovery than patients who had experienced a less severe acute illness. We also hypothesized that increased alveolar ventilation, if present post-COVID-19, would be related to the degree of shunt and/or dead space present. Accordingly, we measured intrapulmonary shunt alveolar dead space, and relative alveolar ventilation in a cohort of post-COVID-19 patients (n = 59), studied at up to 403 days post-acute illness, and also determined the risk factors for ongoing pulmonary gas exchange impairment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Post-COVID-19 patients.

In this cross-sectional observational study, 59 patients (never-vaccinated for COVID-19) previously diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection by PCR-positive nasal swab between March 2020 and January 2021 at Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia were recruited from a routine follow-up clinic and studied between 15 and 403 days [152.3 ± 85.4 (means ± SD)] after their initial positive PCR test. None of these subjects were part of our previous study (3, 12).

Recruitment was open to all post-COVID-19 patients irrespective of the severity of acute illness, whether managed at home or in hospital, and whether or not they were experiencing any ongoing symptoms. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. Of the 59 participants, 44 had not required admission for their acute disease episode; however, 15 patients had been admitted, with 7 requiring supplemental oxygen (5 via high flow nasal cannula), and 5 requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation.

All patients were studied between June 2020 and May 2021, following protocol approval by the western Sydney local health district human research ethics committee (HREC: 2020/ETH01610), and all gave written informed consent. A data use agreement allowed the sharing of data among the coauthors.

Acute COVID-19 Severity (NIH Category)

Based on the medical record, patients were categorized using NIH COVID-19 severity categories (13), (NIH-1: asymptomatic; NIH-2: any symptom of COVID-19 but no dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging; NIH-3: evidence of a lower respiratory disease during clinical assessment or imaging, however, oxygen saturations ≥ 94%; NIH-4: either oxygen saturation < 94%, / < 300 mmHg, respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrates > 50%; NIH-5: respiratory failure, septic shock and/or multiple organ dysfunction).

Ancillary Data

Patient characteristics recorded included anthropometrics, smoking history, previous non-COVID-19 diagnoses such as hypertension, diabetes, lung or heart disease, date of SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity, and whether hospitalized for COVID-19 (including oxygen administration or intubation). Respiratory symptoms, at the time of follow-up, including cough and breathlessness, were recorded.

Pulmonary Shunt and Alveolar Dead Space

Theoretical basis.

The theory underlying the “bedside methodology” we used to quantify intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space using exhaled and arterial blood gas analyses has been previously presented in detail (10) and has also been the subject of recent editorial review (14).

Methodology.

For the present study, the methodology protocol was similar to that outlined in our previous publication (3). In brief, seated subjects wore a nose clip while breathing ambient air on a mouthpiece with attached pneumotachometer and gas sampling connection, allowing continuous monitoring of inhaled and exhaled oxygen, carbon dioxide, and airflow (Medgraphics Ultima PFX, MGC Diagnostics, Saint Paul, MN). Data were collected at 100 Hz for ∼2 min and stored as raw time-based voltage signals for later determination of mean alveolar Po2 and Pco2. Immediately afterwards, during steady state breathing (i.e., end-tidal CO2 changing by < 2 mmHg over four consecutive breaths), arterial blood (∼1 mL) was collected over two to three breaths from a radial artery puncture using a heparinized syringe (Radiometer PICO70 with 25-gauge needle) and analyzed within 3 min (Radiometer ABL800 FLEX gas analyzer, maintained at 37°C).

Data Analysis

Arterial blood gas analysis.

Arterial blood pH, , and were recorded and assumed to be at 37°C.

Exhaled gas analysis.

Time-based voltage data were exported into MATLAB. Imported data were adjusted for lag time due to 1) the transport delay time [time from flow reversal to start of the fall in CO2 (or rise in O2) toward inspired at the end of a breath], and 2) the time it takes from that start of end-tidal change toward inspired to reach the half-way mark (i.e., to the average of end-tidal and inspired) (15).

Voltage data for O2 and CO2 (100 Hz) were converted to partial pressures using calibration curves. Minor differences in day-to-day calibration were accounted for by rescaling so that the inspired and end-tidal values for both gases matched corresponding partial pressures available from the Medgraphics outputs collected at the time of arterial blood sampling.

Calculation of alveolar partial pressures and alveolar-arterial partial pressure differences.

Three separate breaths were selected, independently analyzed, and resulting parameters averaged. Following alignment of gas and volume signals, Po2 and Pco2 values for each breath were plotted as a function of expired volume, and a linear least-squares fit applied to the alveolar plateau. Mean alveolar gas values, , and (10) at the midpoint (by volume) of the expired breath were determined from the fitted lines. Alveolar-arterial partial pressure differences for both O2 and CO2 were then calculated as – (AaPo2) and − (aAPco2).

Shunt and alveolar dead space.

Shunt and alveolar dead space were derived from the alveolar arterial differences for the two gases as has been previously described in detail (10). Using the three-compartment model of Riley and Cournand (16), in which the lung is considered to consist of: 1) an intrapulmonary shunt compartment with an alveolar ventilation/perfusion ratio (V̇a/Q̇ of 0, also encompassing regions of very low V̇a/Q̇, 2) an alveolar dead space compartment with V̇a/Q̇ of infinity, also encompassing regions of very high V̇a/Q̇, and 3) the remainder of the lung, with a V̇a/Q̇ ratio given by non-dead space ventilation divided by nonshunt blood flow.

Briefly the analysis runs as follows. First, both AaPo2 and aAPco2 are each affected by both intrapulmonary shunt (and low V̇a/Q̇ regions) but also by alveolar dead space (and high V̇a/Q̇ regions), as explained previously (10) (see Fig. 1). The analysis uses both AaPo2 and aAPco2 to simultaneously determine the amount of intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space that together would uniquely yield the measured alveolar-arterial differences for both gases. This is achieved using the computer program published by West in 1969 (17). First, the multicompartment log-normal V̇a/Q̇ distribution model is replaced with the three-compartment model (16). Following this, rather than using West’s computer model in the intended manner to determine arterial and expired pO2 and pCO2, and hence the arterial-alveolar differences, the program is run in reverse, allowing the intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space that would result in the measured alveolar-arterial differences to be determined. Several other variables are required in addition to the measured alveolar-arterial differences, and these include body temperature (assumed to be 37°C), acid-base status and hemoglobin (both measured on the arterial blood gas), ventilation, V̇o2, V̇co2, and (all measured during expired gas analysis). Hemoglobin P50 was assumed to be 27 mmHg, and the cardiac output was estimated from the empirical relationship with oxygen uptake as 5×V̇o2 + 5 (18), which are reasonable assumptions that do not greatly impact on shunt estimation (10). Importantly, the dead space compartment reflects only alveolar dead space, being based on the differences between arterial and mean alveolar Po2 and Pco2. Thus, anatomic dead space is excluded.

Figure 1.

Alveolar-arterial differences for Po2 (AaPo2) and Pco2 (aAPco2) across the indicated combinations of shunt and dead space, each from 0 to 50%. The grid can be used to estimate both shunt and alveolar dead space for any combination of AaPo2 and aAPco2. Note that the position of each point on the grid is dependent on a number of ancillary variables including pH, Hb, Hb P50, temperature, base excess, V̇e, cardiac output, V̇co2, and V̇o2, with all except cardiac output and Hb P50 automatically available from either the expired gas or arterial blood samples used to measure AaPo2 and aAPco2. Reproduced by editorial request, and modified from Wagner et al. (10). aAPco2, arterial- alveolar partial pressure difference for carbon dioxide; AaPo2, alveolar-arterial partial pressure difference for oxygen; V̇o2, oxygen consumption in L/min; V̇co2, carbon dioxide production in L/min.

Methodological validation.

As a validation of methodology used in the present study, we measured intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space in seven healthy adults [no history of COVID-19; 3 males, age 32.9 ± 14.7 yr (means ± SD), body mass index (BMI) 24.6 ± 2.3 kg/m2].

Comparison with traditional measurements of gas exchange.

Bohr-Enghoff dead space (%) was calculated for each subject using the measured mixed expired CO2 () and , Bohr-Enghoff Dead Space % = × 100 and plotted against measured alveolar dead space.

In addition, AaO2 was calculated using

using R, , and measured in the exhaled gases.

Relative ventilation.

We also assessed each patient’s level of alveolar ventilation by calculating the term 40/, designated as VArel, which indicates alveolar ventilation relative to what would be present if had been 40 mmHg. VArel was plotted against (12), , shunt and alveolar dead space and alveolar dead space plotted against . For comparison, historical healthy young subject data (19–21) were used.

Statistical analysis.

Continuous data were pooled and reported as mean and standard deviation for parametric data or median and interquartile range (IQR) for nonparametric data. Categorical data were summarized by proportions and counts. NIH severity score of 1 or 2 was grouped and classified as “low-medium severity” subgroup, while NIH scores of 3, 4, or 5 were grouped and classified as “severe-critical severity” subgroup. As previously, 95% confidence limits for intrapulmonary shunt were defined as <5% and normal alveolar dead space as <10%, based on the values derived from the healthy subjects using the multiple inert gas elimination technique (11, 17).

Univariate comparisons were tested via Mann–Whitney U tests. Correlations were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Univariate and multivariate Gaussian regression models were used to examine relationships between gas exchange parameters (shunt and alveolar dead space) and acute COVID-19 illness severity (NIH category), time since acute illness, age, BMI, and comorbid diabetes/hypertension.

Statistical analyses were completed using Prism 9 (Version 9.5.1, GraphPad Software LLC, Boston, MA) or Stata SE V. 14.2 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient Data

Patients were between 19 and 81 yr of age (average 50.4 ± 16.1 yr) with a BMI of 30.7 ± 8.4 kg/m2. We studied 33 women and 26 men. Fourteen (23.7%) had a history of any smoking, 3 (5.1%) had a more than 10 pack yr history, 2 (3.4%) had a diagnosis of asthma, 9 (15.3%) had a diagnosis of diabetes, 12 (20.3%) had hypertension, and 3 (5.2%) known cardiovascular disease. Forty-four (74.6%) had previous mild-moderate COVID-19 (6 NIH-1, 38 NIH-2), while 15 (25.4%) had previous severe-critical COVID-19 (3 NIH-3, 7 NIH-4, 5 NIH-5). Patients were studied between 15 and 403, a median of 127 (95–186) days after first SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive test.

Respiratory Symptoms

Respiratory symptoms were documented in 51/59 patients at follow-up. Of these, 9 (18%) patients complained of a cough, 23 (45%) patients complained of breathlessness, and 5 (10%) patients complained of wheeze. Overall, 25 (49%) of patients had at least one respiratory symptom (cough, breathlessness, and/or wheeze).

Arterial Blood Gas and Exhaled Gas Data

Figure 2 shows the group arterial blood gas and exhaled gas data grouped by NIH severity. Patients with a history of Low-Medium COVID-19 severity had a significantly higher [94.0 (88.7–101.8) mmHg, compared with those with Severe-Critical COVID-19 severity (87.1 (83.3–91.0) mmHg: P < 0.005].

Figure 2.

Individual data for 59 post-COVID-19 patients NIH 1-2 (44 patients with low-medium severity, open blue circles) and NIH 3-5 (15 patients with severe-critical severity, enclosed red squares) for arterial Po2 (A), arterial Pco2 (B), alveolar Po2 (C), and alveolar CO2 (D). **P < 0.005 compared to low-medium severity. Black horizontal line represents median value. COVID-19, 2019 Novel Coronavirus; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

The average hemoglobin for female patients (n = 26) was 131 (123–138) g/L, and the average for male subjects was 145 (135–155) g/L.

Shunt and Alveolar Dead Space

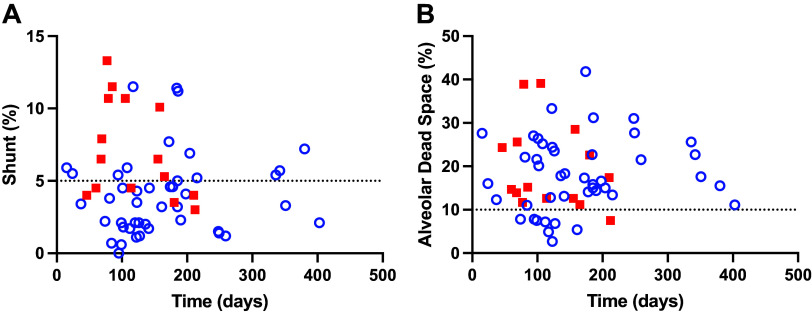

Figure 3 shows the individual data for alveolar-arterial differences, and shunt and alveolar dead space values. Median AaPo2 values were significantly higher in NIH category 3–5 compared to NIH category 1–2 subgroup [24.7 (18.6–33.9) mmHg vs. 16.9 (11.0–25.8) mmHg; P < 0.008]. Median shunt values were also significantly higher in the NIH category 3–5 subgroup than in the NIH category 1–2 group [6.5 (−0.2 to 13.2) % vs. 3.5(−0.1 to 7.0) %, P < 0.01]; however, there was no significant difference in aAPco2 or alveolar dead space between the subgroups.

Figure 3.

Individual data for 59 post-COVID-19 patients NIH 1-2 (44 patients, low-medium severity, open blue symbols) and NIH 3-5 (15 patients, severe-critical severity, closed red squares) showing AaPo2 mmHg (A), aAPco2 mmHg (B), shunt (C), and alveolar dead space (D). **P < 0.008 compared to low-medium severity. Black horizontal line represents median values, dotted lines represent 95% confidence levels for shunt (5%), and alveolar dead space (10%) from healthy subjects (11). aAPco2, arterial- alveolar partial pressure difference for carbon dioxide; AaPo2, alveolar-arterial partial pressure difference for oxygen; COVID-19, 2019 Novel Coronavirus; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Figure 4 shows the relationships between alveolar-arterial differences, and shunt and alveolar dead space values for methodological controls and for post-COVID-19 patients. All of the methodological control data lies within, or close to, the 95% confidence levels, indicating technical adequacy of the AaPo2 and aAPco2 measurement. Only 8 of the 59 patients (13.5%) had shunt values < 5% and alveolar dead space values < 10%. One (1.6%) patient had increased shunt but normal alveolar dead space, while 21 (35.5%) had both increased shunt and alveolar dead space, and 29 (49.2%) had increased dead space only. Thus, 37% had elevated shunt and 86% had elevated dead space. There was no correlation between shunt and alveolar dead space (P = 0.07). There were no differences between shunt and alveolar dead space between those with or without shortness of breath (P = 0.4 and 0.49, respectively).

Figure 4.

Individual data from 7 healthy subjects (closed black triangles; A and C) and for 59 post-COVID-19 patients (B and D) NIH severity 1–2 (44 patients; open blue circles) and NIH severity 3–5 (15 patients; closed red squares) showing: measured AaPo2 mmHg and aAPco2 mmHg (A and B) and calculated shunt and alveolar dead space values (C and D). Dotted lines represent 95% confidence levels for shunt (5%), and alveolar dead space (10%) from healthy subjects (11). Note that the healthy subjects’ data lie within, or close to, the 95% confidence levels, indicating technical adequacy of the AaPo2 and aAPco2 measurements. aAPco2, arterial- alveolar partial pressure difference for carbon dioxide; AaPo2, alveolar-arterial partial pressure difference for oxygen; COVID-19, 2019 Novel Coronavirus; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Comparison with Bohr-Enghoff Dead Space and Calculations Using the Alveolar Gas Equation

Bohr-Enghoff dead space calculated using either measured mixed expired CO2, and alveolar-arterial calculated using the alveolar gas equation plotted against alveolar dead space and measured AaPo2 are shown in Fig. 5. This plot shows that Bohr-Enghoff dead space measurements are much greater than the measured alveolar dead space measurement, and AaO2 gradient calculation underestimates the true AaO2 gradient. There were significant linear relationships between Bohr-Enghoff dead space and alveolar dead space (R2 0.65, P < 0.0001) and calculated and measured AaO2 gradient (R2 0.8, P < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

Individual data for 59 subjects for Bohr-Enghoff dead space [calculated as × 100] plotted against measured alveolar dead space as described in the text (A) and AaPo2 from the standard alveolar gas equation, where = − /R + × × (1−R)/R plotted against AaPo2 using measured as described in the text (B). Lines of identity are in red, linear regression lines in black. Note that Bohr-Enghoff dead space measurements are much greater than the measured alveolar dead space measurement and AaO2 gradient calculation underestimates the true AaO2 gradient. AaPo2, alveolar-arterial partial pressure difference for oxygen; , fraction of inspired oxygen; , partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide; , partial pressure of alveolar oxygen; , partial pressure of inspired oxygen.

Acute Illness Severity Category

Figure 6 presents the shunt and dead space for post-COVID-19 patients plotted against time since infection grouped by NIH severity category. There were no significant differences between patient subgroups in time from first positive PCR, age, height, weight, smoking prevalence, or previous diagnosis of asthma (all P > 0.05). Patients in the severe-critical category were significantly more obese [BMI: 34.3(27.8–38.3) kg/m2 vs. 28.0 (25.3–31.1) kg/m2; P < 0.01], and more likely to have a previous diagnosis of diabetes [8 (NIH 3–5) vs. 1 (NIH 1–2)] or hypertension [8 (NIH 3–5) vs. 4 (NIH 1–2); both P < 0.01].

Figure 6.

Individual data for 59 post-COVID-19 patients for shunt (A) and alveolar dead space (B) plotted against time since acute SARS-CoV-2 infection for post-COVID-19 patients with low-medium severity (44 patients, NIH-1 and 2, open blue circles) and severe-critical severity (15 patients, NIH-3-5, closed red squares). Dotted lines represent 95% confidence levels for shunt (5%), and alveolar dead space (10%) from healthy subjects (11). COVID-19, 2019 Novel Coronavirus; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Outcomes from Regression Models

For shunt, there were significant univariate relationships with: BMI [0.11 (0.02–0.21) % per kg/m2], (95% confidence interval, P = 0.02), age [0.05 (0.00–0.11) % per year, P = 0.04], and acute illness NIH severity category [3.1 (1.34–4.86) % per category, P < 0.01]. However, in the multivariate models, only NIH severity category was a significant predictor for shunt [2.69% per category (0.82–4.57), P < 0.01]. For alveolar dead space, there was a small, but significant, univariate relationship with age [1.6 (0.2–3.0% per decade, P = 0.03], which was also present in the multivariate model [1.6 (0.1–3.2) % per decade, P < 0.04]. Shunt and alveolar dead space are shown as a function of time since acute SARS-CoV-2 infection for each NIH severity category in Fig. 6.

Relative Alveolar Ventilation

Ventilation was commonly elevated above expected levels for the post-COVID-19 patients (Fig. 7), and this finding was seen at all values of , , shunt, and alveolar dead space (Fig. 7). For the 13 patients with a < 35 mmHg, the average pH was 7.47 ± 0.03 (range 7.39–7.51), and 9 patients had a pH > 7.45, indicating that some patients were acutely hyperventilating. There was a significant correlation between VArel and (r−0.76, P < 0.0001 and between VArel and shunt (r 0.27, P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Individual data for 59 post-COVID patients NIH severity 1–2 (44 patients, open blue circles), and NIH severity 3–5 (15 patients, closed red squares) and methodological controls (7 subjects, black triangles) for relative ventilation plotted against (A), intrapulmonary shunt (B), (C), alveolar dead space (D), and plotted against alveolar dead space (E). For comparison in A, historical data from healthy controls for Wagner et al. [closed black circles (19)], Torre-Bueno et al. [open black circles (21)] and Hammond et al. [closed black squares (20)] are also plotted. Vertical line 5% shunt (B), = 40 mmHg (C), 10% alveolar dead space (D), = 40 mmHg (E). Curved lines in C represents VArel = 40/, VArel = 40/( − 5), and VArel = 40/( − 10) if = , and horizonal line is at VArel= 1.0. Horizontal line in E is at alveolar dead space = 10%. COVID-19, 2019 Novel Coronavirus; NIH, National Institutes of Health; , partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide; , partial pressure of alveolar carbon dioxide; , partial pressure of arterial oxygen; VArel, 40/= relative alveolar ventilation.

There were no differences in VArel between patients who complained of breathlessness to those who did not (P = 0.1).

DISCUSSION

Using a recently developed methodology measuring exhaled gas and simultaneous arterial gas measurements to quantify intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space (3, 10, 14), the principal, novel, findings of our study are: 1) up to 403 days following an acute COVID-19 illness, intrapulmonary shunt remains increased in 37% of patients with alveolar dead space elevated in 86%; 2) shunt and alveolar dead space were not correlated, reinforcing the suggestion that they reflect independent pathological processes, 3) elevated shunt was partially related to the severity of the acute illness, while increased alveolar dead space was not. However, alveolar dead space was weakly related to increasing age. Based on multivariate analysis, there were no other predictors for shunt or dead space, including time since acute infection, BMI, and comorbid disease. 4) The majority of the patients had increased ventilation regardless of history of disease severity, which was not related to symptoms.

Contrary to our hypothesis, time since acute infection with SARS-CoV-2 (15 days–13 mo) was not associated with a reduction in shunt or alveolar dead space, although there are limited data beyond 200 days. This finding suggests persistence of COVID-19 pulmonary pathology such as pulmonary fibrosis, chronic pulmonary vascular obstruction, or angiogenesis (5, 7, 22).

In contrast to our previous study (3), the majority of patients in this study have persistent gas exchange abnormalities at recovery. The patients in this current study were studied later, were more obese, of a similar age, and more women were included. This study also included more severe patients, and more patients required intubation and ventilation. These characteristics may be contributing to the greater prevalence of gas exchange abnormalities seen in this current study. In addition, it is likely that there is an overrepresentation of symptomatic patients as these patients remained in contact with health care providers.

Measurement of Intrapulmonary Shunt and Dead Space

The technique used to quantify intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space was developed by Wagner et al (10). Methodological controls in this study fell within or close to published values for the 95% confidence levels for shunt (5%), and alveolar dead space (10%) in healthy adults (11). The advantages of this technique are that it directly measures alveolar gas, allowing accurate estimation of intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space. It can be used in the setting of an infectious illness, as we have previously shown in acute COVID-19 (3). When compared to estimates of Bohr-Enghoff dead space, our measurements of alveolar dead space are less, likely as a consequence of anatomical dead space included in the Bohr-Enghoff dead space. Alveolar gas equation estimates of alveolar-arterial oxygen difference also underestimate the true difference. This is a consequence of the alveolar-arterial carbon dioxide difference. In a recent editorial, this methodology was described as a big step forward in gas exchange physiology which should be applied to other pulmonary conditions (14). Indeed, this methodology represents a simple bedside test which can be used more widely than other methods such as multiple inert gas elimination technique (23).

Intrapulmonary Shunt

As we hypothesized, patients with more severe disease were more likely to have a larger shunt. The NIH severity category largely uses measures of oxygenation to categorize severity (13), suggesting its construction reflects the magnitude of shunts in the lung. Shunt is a consequence of many pathological processes including: 1) alveolar filling with fluid or cell debris, 2) atelectasis, or 3) small airways obstruction that alone or in combination reduce or eliminate ventilation of affected alveoli. From the medical record, most patients had a clear chest radiograph at follow-up, while 25% showed some atelectasis. This finding suggests that post-COVID-19, alveolar collapse/and or airway filling may not be the cause of increased intrapulmonary shunt. However, it is worth noting that open but poorly ventilated alveoli could contribute to the widening of the AaPo2, and thus to measured shunt may not be visible on CXR. An increase in shunt may also be a consequence of an increase in anastomotic blood vessels, with angiogenesis and new blood vessel formation reported in the acute illness (22), which if they bypassed alveolar gas would contribute to shunt.

Alveolar Dead Space

The increase in alveolar dead space implies reduced regional alveolar perfusion relative to the ventilation and may be a consequence of persistent vascular damage, redistribution of blood flow from vascular obstruction, or hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in those portions of the lung. Microembolic disease is reported in the acute infection (22, 24, 25), and plasma samples in post-COVID-19 patients with persistent COVID-19 symptoms 6 mo after their acute illness have increased microclots in their circulation (26). In addition, increased dead space may be a consequence of “microischemia,” leading to fibrotic remodeling (27–29).

Recently an increase in alveolar dead space in hospitalized patients recovering from COVID-19 has been reported using computed cardiopulmonography (30). Unlike our study, there was a relationship with severity of disease, with patients treated in ICU more likely to have an increase in alveolar dead space. Many of the patients included in our study had mild disease, yet despite this had increased alveolar dead space during recovery, suggesting that this finding may be a common sequel to an acute COVID-19 infection rather than an outcome only of severe disease.

Age was a weak predictor of an increase in alveolar dead space in post-COVID-19 patients. The effect of age may be due to the known age-related increase in alveolar dead space (31). COVID-19 severity has a known interaction with age and is more likely to be fatal in older people (32, 33). However, the effect of age itself was very small (only a 1.6% increase in alveolar dead space per decade) in comparison to the degree of elevation of dead space, and cannot explain the majority of the increased alveolar dead space. Thus, predictors of the increase in alveolar dead space, which was highly variable and as high as 30–40% in some post-COVID-19 patients remain unknown.

Alveolar Dead Space and Hyperventilation Contributions to VArel

Relative ventilation was higher than expected in the majority of patients regardless of disease severity, similar to patients with acute COVID-19 pneumonitis (12), and none had a relative ventilation less than 1. None of the methodological controls were hyperventilating. There was evidence of acute hyperventilation, with some of the post-COVID-19 patients with a less than 35 mmHg having evidence of an acute respiratory alkalosis. For post-COVID-19 patients, there was no relationship to the degree of hypoxemia, and Fig. 7A shows that arterial exceeds 75 mmHg in all patients, and furthermore has no correlation with . The frequency of elevated arterial-alveolar CO2 gradients in post-COVID-19 patients is evident from Fig. 7C, as all the measurements lie above an aACO2 of 0. There was a weak correlation between shunt and relative ventilation (Fig. 7B, r 0.26, P < 0.04), suggesting that increased shunt was trivially contributing to the increase in ventilation. There was no relationship with the increase in alveolar dead space (Fig. 7, r 0.20, P = 0.13), which was unexpected. Indeed, in those patients with a low arterial CO2, alveolar dead space was often within the 95% confidence limits, suggesting increased alveolar dead space is not contributing to hyperventilation.

Post-COVID-19, many patients report an increase in breathlessness (34). In our patient cohort, at least 45% of the patients complained of some degree of breathlessness, there were no differences in alveolar dead space or shunt between patients with shortness of breath and those without, although breathlessness was not quantified systematically. The mechanisms that may explain the increase in ventilation post-COVID-19 have been previously discussed in the setting of acute COVID-19 pneumonitis (12). These included genetic differences in hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) (35, 36), previous sustained hypoxemia resulting in an increase in HVR (37), invasion of the carotid body (35), or central nervous system (38) by SARS-COV-2, or disease-related factors impacting on ventilatory control or respiratory mechanics. As the majority of these patients have no history of significant hypoxemia, chronic changes in the HVR seem unlikely, as does mechanical changes in the lung. Additional studies would be required to establish the roles of these contributing factors. It remains unexplained why such a large proportion of post-COVID-19 patients have elevated alveolar ventilation.

Limitations

We defined the 95% confidence upper limit for normal values for intrapulmonary shunt as < 5% and for normal alveolar dead space as < 10%. These limits were based on published values for healthy subjects determined using the multiple inert gas elimination technique (MIGET) (11). Our rationale for using these data is as follows. When coupled with West’s computer program (17), MIGET input datasets allow prediction of , , mean alveolar Po2 and Pco2, and physiological shunt and alveolar dead space. Our input data were analyzed using the same software (17). This means that the processing of the raw data inputs from both studies is identical. Consequently, the published MIGET data (11) do provide directly appropriate comparator reference values for use in the present study.

It is possible that measurement error of aAPco2 (a small difference between two large numbers) may have dominated the measurements, contributing to error. If so, it would have been evident as many zero or negative aAPco2 values, however, that was not frequently seen. Rather, the values obtained from the methodological controls under the same conditions all fell within, or close to, the 95% confidence levels, indicating the methodology is technically accurate.

Relative ventilation was quantified as 40/alveolar Pco2. In contrast to more standard methods of quantifying ventilation such as V̇E/ V̇co2, this method of quantifying ventilation represents the ventilation of the alveoli alone because alveolar Pco2 is measured from the expired gas alveolar plateau recorded from each breath. None of the methodological controls had an increase in relative ventilation, again indicating that the methodology is technically accurate.

This is a cross-sectional study, and findings may vary within an individual over time. Patients were studied early in the pandemic, and before introduction of vaccination or specific anti-viral medications, which may modify the response/recovery to infection. Patients were recruited from a clinic that was established to follow-up all patients who had presented to hospitals in western Sydney. This may have resulted in a selection bias, with greater recruitment of symptomatic patients who may have had an increased prevalence of gas exchange abnormalities than patients without symptoms, possibly resulting in an overrepresentation of gas exchange abnormalities. The majority of our patients contracted COVID-19 in 2020, and these findings may not be generalizable to more recent viral strains. In addition, there may be an effect of different therapies on the results, although as the majority of our cohort were not hospitalized and did not receive any particular therapy this seems unlikely. In addition, we do not have control data measuring shunt and dead space with increasing age and BMI, and it may be that these statistical associations are not a consequence of COVID-19.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Using direct measurement of the alveolar-arterial differences to quantify intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space (10), we demonstrated 15–403 days after an infection with SARS-CoV-2 alveolar dead space was elevated in 86% of patients, and increased intrapulmonary shunt in 37% of patients. The time since infection was not a predictor of either increased alveolar dead space or intrapulmonary shunt, suggesting persistent pulmonary vascular and parenchymal pathology, with shunt likely resulting from alveolar and airway damage or relatively increased perfusion, and dead space likely resulting from microemboli causing loss of alveolar perfusion. These abnormalities may contribute to ongoing COVID-19 symptoms, and may in part also explain why post-COVID-19 patients are at risk of readmission for respiratory illness (39).

NIH COVID-19 severity, although predictive of shunt in multivariate models, does not cleanly separate patients with lower shunts from those with higher shunts, and, importantly, does not identify patients with high alveolar dead space, suggesting that persistent parenchymal and/or pulmonary (micro) vascular pathology occurs regardless of acute COVID-19 severity. An increase in relative alveolar ventilation, associated with higher shunts, was present in the majority of post-COVID-19 patients, and may contribute to some of the dyspnea and breathlessness which is reported in between 7 and 61% of post-COVID patients (34, 40–42).

It remains to be determined whether the shunt, alveolar dead space, and ventilation abnormalities observed in some post-COVID-19 patients are related to the cluster of symptoms known as “long COVID” (34, 43), and whether they persist even longer or eventually resolve over time.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

Dr. A. Malhotra is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

A.M. has received consulting fees for medical education from Livanova, Eli Lilly, Zoll, and Jazz. ResMed provided a philanthropic donation to UCSD. P.D.W. has received consulting fees from SMS Biotechnology and Third pole inc. G. Prisk is an editor of Journal of Applied Physiology and was not involved and did not have access to information regarding the peer-review process or final disposition of this article. An alternate editor oversaw the peer-review and decision-making process for this article. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.E.F., G.K.P., A.M., T.C.A., P.D.W., and K.K. conceived and designed research; C.E.F. and R.A.R. performed experiments; C.E.F., G.K.P., T.C.A., P.D.W., and K.K. analyzed data; C.E.F., G.K.P., A.M., T.C.A., P.D.W., and K.K. interpreted results of experiments; K.K. prepared figures; T.C.A., P.D.W., and K.K. drafted manuscript; C.E.F., G.K.P., T.C.A., P.D.W., and K.K. edited and revised manuscript; C.E.F., R.A.R., G.K.P., P.H., A.M., T.C.A., P.D.W., and K.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank James Elhindi for statistical assistance, Westmead Hospital Respiratory Function Laboratory Staff for assistance with respiratory data collection, and medical, nursing and allied health staff of Westmead Hospital for clinical data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 382: 727–733, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Habashi NM, Camporota L, Gatto LA, Nieman G. Functional pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2-induced acute lung injury and clinical implications. J Appl Physiol (1985) 130: 877–891, 2021. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00742.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harbut P, Prisk GK, Lindwall R, Hamzei S, Palmgren J, Farrow CE, Hedenstierna G, Amis TC, Malhotra A, Wagner PD, Kairaitis K. Intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space in a cohort of patients with acute COVID-19 pneumonitis and early recovery. Eur Respir J 61: 2201117, 2023. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02287-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497–506, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tarraso J, Safont B, Carbonell-Asins JA, Fernandez-Fabrellas E, Sancho-Chust JN, Naval E, Amat B, Herrera S, Ros JA, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Rodriguez-Portal JA, Andreu AL, Marín M, Rodriguez-Hermosa JL, Gonzalez-Villaescusa C, Soriano JB, Signes-Costa J; COVID-FIBROTIC study team. Lung function and radiological findings 1 year after COVID-19: a prospective follow-up. Respir Res 23: 242, 2022. doi: 10.1186/s12931-022-02166-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taverne J, Salvator H, Leboulch C, Barizien N, Ballester M, Imhaus E, Chabi-Charvillat ML, Boulin A, Goyard C, Chabrol A, Catherinot E, Givel C, Couderc LJ, Tcherakian C. High incidence of hyperventilation syndrome after COVID-19. J Thorac Dis 13: 3918–3922, 2021. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hama Amin BJ, Kakamad FH, Ahmed GS, Ahmed SF, Abdulla BA, Mohammed SH, Mikael TM, Salih RQ, Ali RK, Salh AM, Hussein DA. Post COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis; a meta-analysis study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 77: 103590, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grist JT, Chen M, Collier GJ, Raman B, Abueid G, McIntyre A, Matthews V, Fraser E, Ho LP, Wild JM, Gleeson F. Hyperpolarized (129)Xe MRI abnormalities in dyspneic patients 3 months after COVID-19 pneumonia: preliminary results. Radiology 301: E353–E360, 2021. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grist JT, Collier GJ, Walters H, Kim M, Chen M, Abu Eid G, Laws A, Matthews V, Jacob K, Cross S, Eves A, Durrant M, McIntyre A, Thompson R, Schulte RF, Raman B, Robbins PA, Wild JM, Fraser E, Gleeson F. Lung abnormalities detected with hyperpolarized (129)Xe MRI in patients with long COVID. Radiology 305: 709–717, 2022. doi: 10.1148/radiol.220069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner PD, Malhotra A, Prisk GK. Using pulmonary gas exchange to estimate shunt and deadspace in lung disease: theoretical approach and practical basis. J Appl Physiol (1985) 132: 1104–1113, 2022. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00621.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wagner PD, Hedenstierna G, Bylin G. Ventilation-perfusion inequality in chronic asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 136: 605–612, 1987. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kairaitis K, Harbut P, Hedenstierna G, Prisk GK, Farrow CE, Amis T, Wagner PD, Malhotra A. Ventilation is not depressed in patients with hypoxemia and acute COVID-19 infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 205: 1119–1120, 2022. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2025LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines (Online). National Institutes of Health. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ [Accessed 9 August 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hughes M. Novel gas exchange analysis in COVID-19 lung disease. Eur Respir J 61: 2201962, 2023. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01962-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bates JH, Prisk GK, Tanner TE, McKinnon AE. Characterizing and correcting for the dynamic response of a bag-in-box system. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 56: 254–258, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.1.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riley RL, Cournand A. Ideal alveolar air and the analysis of ventilation-perfusion relationships in the lungs. J Appl Physiol 1: 825–847, 1949. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1949.1.12.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. West JB. Ventilation-perfusion inequality and overall gas exchange in computer models of the lung. Respir Physiol 7: 88–110, 1969. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(69)90071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Astrand PO, Cuddy TE, Saltin B, Stenberg J. Cardiac output during submaximal and maximal work. J Appl Physiol 19: 268–274, 1964. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wagner PD, Gale GE, Moon RE, Torre-Bueno JR, Stolp BW, Saltzman HA. Pulmonary gas exchange in humans exercising at sea level and simulated altitude. J Appl Physiol (1985) 61: 260–270, 1986. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.1.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hammond MD, Gale GE, Kapitan KS, Ries A, Wagner PD. Pulmonary gas exchange in humans during normobaric hypoxic exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 61: 1749–1757, 1986. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.5.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torre-Bueno JR, Wagner PD, Saltzman HA, Gale GE, Moon RE. Diffusion limitation in normal humans during exercise at sea level and simulated altitude. J Appl Physiol (1985) 58: 989–995, 1985. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.3.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, Vanstapel A, Werlein C, Stark H, Tzankov A, Li WW, Li VW, Mentzer SJ, Jonigk D. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 383: 120–128, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wagner PD, Saltzman HA, West JB. Measurement of continuous distributions of ventilation-perfusion ratios: theory. J Appl Physiol 36: 588–599, 1974. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vrints CJM, Krychtiuk KA, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Segers VF, Price S, Heidbuchel H. Endothelialitis plays a central role in the pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 and its cardiovascular complications. Acta Cardiol 76: 109–124, 2021. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2020.1846921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Price LC, Ridge C, Wells AU. Pulmonary vascular involvement in COVID-19 pneumonitis: is this the first and final insult? Respirology 26: 832–834, 2021. doi: 10.1111/resp.14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pretorius E, Vlok M, Venter C, Bezuidenhout JA, Laubscher GJ, Steenkamp J, Kell DB. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20: 172, 2021. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ackermann M, Mentzer SJ, Kolb M, Jonigk D. Inflammation and intussusceptive angiogenesis in COVID-19: everything in and out of flow. Eur Respir J 56: 2003147, 2020. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03147-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ackermann M, Tafforeau P, Brunet J, Kamp JC, Werlein C, Kühnel MP, Jacob J, Walsh CL, Lee PD, Welte T, Jonigk DD. Reply to: intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space in a cohort of patients with acute COVID-19 pneumonitis and early recovery. Eur Respir J 61: 2202287, 2023. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02121-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ackermann M, Kamp JC, Werlein C, Walsh CL, Stark H, Prade V, Surabattula R, Wagner WL, Disney C, Bodey AJ, Illig T, Leeming DJ, Karsdal MA, Tzankov A, Boor P, Kühnel MP, Länger FP, Verleden SE, Kvasnicka HM, Kreipe HH, Haverich A, Black SM, Walch A, Tafforeau P, Lee PD, Hoeper MM, Welte T, Seeliger B, David S, Schuppan D, Mentzer SJ, Jonigk DD. The fatal trajectory of pulmonary COVID-19 is driven by lobular ischemia and fibrotic remodelling. EBioMedicine 85: 104296, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Magor-Elliott SRM, Alamoudi A, Chamley RR, Xu H, Wellalagodage T, McDonald RP, O'Brien D, Collins J, Coombs B, Winchester J, Sellon E, Xie C, Sandhu D, Fullerton CJ, Couper JH, Smith NMJ, Richmond G, Cassar MP, Raman B, Talbot NP, Bennett AN, Nicol ED, Ritchie GAD, Petousi N, Holdsworth DA, Robbins PA. Altered lung physiology in two cohorts after COVID-19 infection as assessed by computed cardiopulmonography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 133: 1175–1191, 2022. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00436.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller RM, Tenney SM. Dead space ventilation in old age. J Appl Physiol 9: 321–327, 1956. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1956.9.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Romero Starke K, Reissig D, Petereit-Haack G, Schmauder S, Nienhaus A, Seidler A. The isolated effect of age on the risk of COVID-19 severe outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health 6: e006434, 2021. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Team C-F. Variation in the COVID-19 infection-fatality ratio by age, time, and geography during the pre-vaccine era: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399: 1469–1488, 2022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02867-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, Redfield S, Austin JP, Akrami A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 38: 101019, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Swenson KE, Ruoss SJ, Swenson ER. The pathophysiology and dangers of silent hypoxemia in COVID-19 lung injury. Ann Am Thorac Soc 18: 1098–1105, 2021. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202011-1376CME. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weil JV. Variation in human ventilatory control-genetic influence on the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 135: 239–246, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hodson EJ, Nicholls LG, Turner PJ, Llyr R, Fielding JW, Douglas G, Ratnayaka I, Robbins PA, Pugh CW, Buckler KJ, Ratcliffe PJ, Bishop T. Regulation of ventilatory sensitivity and carotid body proliferation in hypoxia by the PHD2/HIF-2 pathway. J Physiol 594: 1179–1195, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Monje M, Iwasaki A. The neurobiology of long COVID. Neuron 110: 3484–3496, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ayoubkhani D, Khunti K, Nafilyan V, Maddox T, Humberstone B, Diamond I, Banerjee A. Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 372: n693, 2021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sonnweber T, Sahanic S, Pizzini A, Luger A, Schwabl C, Sonnweber B, et al. Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID-19: an observational prospective multicentre trial. Eur Respir J 57, 2021. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03481-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Billig Rose E, Shapiro NI, Files DC, Gibbs KW, Erickson HL, Steingrub JS, Smithline HA, Gong MN, Aboodi MS, Exline MC, Henning DJ, Wilson JG, Khan A, Qadir N, Brown SM, Peltan ID, Rice TW, Hager DN, Ginde AA, Stubblefield WB, Patel MM, Self WH, Feldstein LR; IVY Network Investigators, CDC COVID-19 Response Team, IVY Network Investigators. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network - United States, March-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69: 993–998, 2020. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 324: 603–605, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang H, Zang C, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Xu J, Bian J, Morozyuk D, Khullar D, Zhang Y, Nordvig AS, Schenck EJ, Shenkman EA, Rothman RL, Block JP, Lyman K, Weiner MG, Carton TW, Wang F, Kaushal R. Data-driven identification of post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection subphenotypes. Nat Med 29: 226–235, 2023. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02116-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.