Abstract

Background

Worldwide there is an increasing demand for Hospital at Home as an alternative to hospital admission. Although there is a growing evidence base on the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of Hospital at Home, health service managers, health professionals and policy makers require evidence on how to implement and sustain these services on a wider scale.

Objectives

(1) To identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative research evidence on the factors that influence the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home, from the perspective of multiple stakeholders, including policy makers, health service managers, health professionals, patients and patients’ caregivers.

(2) To explore how our synthesis findings relate to, and help to explain, the findings of the Cochrane intervention reviews of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, Global Index Medicus and Scopus until 17 November 2022. We also applied reference checking and citation searching to identify additional studies. We searched for studies in any language.

Selection criteria

We included qualitative studies and mixed‐methods studies with qualitative data collection and analysis methods examining the implementation of new or existing Hospital at Home services from the perspective of different stakeholders.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected the studies, extracted study characteristics and intervention components, assessed the methodological limitations using the Critical Appraisal Skills Checklist (CASP) and assessed the confidence in the findings using GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research). We applied thematic synthesis to synthesise the data across studies and identify factors that may influence the implementation of Hospital at Home.

Main results

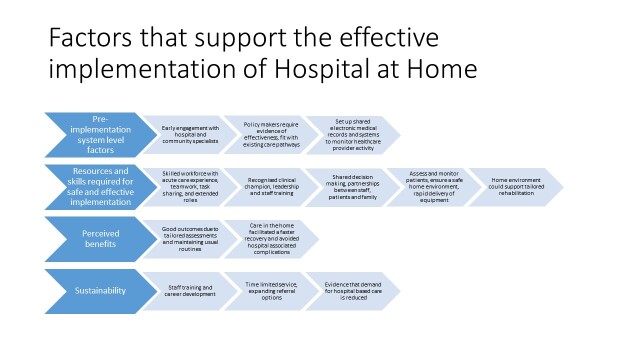

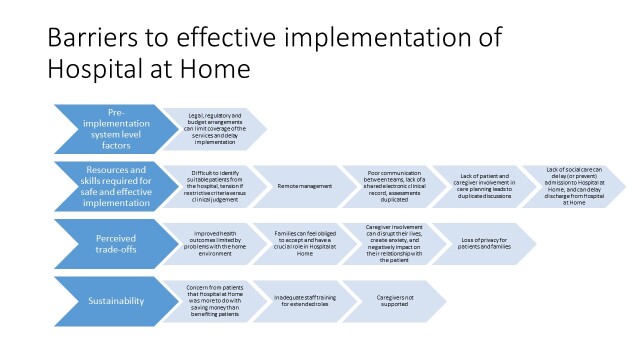

From 7535 records identified from database searches and one identified from citation tracking, we included 52 qualitative studies exploring the implementation of Hospital at Home services (31 Early Discharge, 16 Admission Avoidance, 5 combined services), across 13 countries and from the perspectives of 662 service‐level staff (clinicians, managers), eight systems‐level staff (commissioners, insurers), 900 patients and 417 caregivers. Overall, we judged 40 studies as having minor methodological concerns and we judged 12 studies as having major concerns. Main concerns included data collection methods (e.g. not reporting a topic guide), data analysis methods (e.g. insufficient data to support findings) and not reporting ethical approval. Following synthesis, we identified 12 findings graded as high (n = 10) and moderate (n = 2) confidence and classified them into four themes: (1) development of stakeholder relationships and systems prior to implementation, (2) processes, resources and skills required for safe and effective implementation, (3) acceptability and caregiver impacts, and (4) sustainability of services.

Authors' conclusions

Implementing Admission Avoidance and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services requires early development of policies, stakeholder engagement, efficient admission processes, effective communication and a skilled workforce to safely and effectively implement person‐centred Hospital at Home, achieve acceptance by staff who refer patients to these services and ensure sustainability. Future research should focus on lower‐income country and rural settings, and the perspectives of systems‐level stakeholders, and explore the potential negative impact on caregivers, especially for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home, as this service may become increasingly utilised to manage rising visits to emergency departments.

Keywords: Humans, Administrative Personnel, Checklist, Hospitalization, Hospitals, Patient Discharge

Plain language summary

Multiple perceptions about implementing hospital at home

Key messages

‐ When developing a Hospital at Home service, it is important to set up a straightforward process for healthcare professionals to refer patients. This includes producing clear guidelines that set out who the service is suitable for.

‐ Hospital at Home services need a trained workforce with skills to deliver safe and effective patient‐centred care in the home, with clear and consistent communication between staff, patients and caregivers.

‐ We propose a number of questions for use by healthcare professionals and managers when introducing new Hospital at Home services, or running existing services. The questions are intended to help plan for and implement Hospital at Home services and improve satisfaction and outcomes for staff, patients and caregivers.

What is Hospital at Home?

Hospital at Home provides hospital‐level care at home, for people who would otherwise be inpatients in hospital. One type of Hospital at Home is to avoid admission to hospital. This is called Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home. These services replace an admission to hospital, for people whose condition would normally need treatment in a hospital bed, for example for a flare‐up of a lung condition. Instead, a doctor can refer a patient they assess as being suitable to receive treatment for an illness in their own home (or the place where they usually live, including in residential care), for a limited time. Another type is called Early Discharge Hospital at Home. These services shorten the length of time people need to stay in hospital after being admitted as an inpatient, for example following surgery or treatment for an illness or condition. The care patients would usually receive from healthcare professionals in a hospital bed is instead provided in their home, and is not expected to compromise the quality of care.

What did we want to find out?

Our aim was to find out what is important when introducing, running and receiving care from Hospital at Home services. We wanted to explore a range of experiences of, and views on, Admission Avoidance and Early Discharge services. These might include things that managers want to know when planning to set up a Hospital at Home service, healthcare professionals’ views on working in a Hospital at Home service, what matters to patients who receive this type of care, or how family and caregivers experience Hospital at Home services for those they care for.

What did we do?

We searched for research that had explored experiences, attitudes or beliefs about Hospital at Home services from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, health professionals, managers and health funders. The studies addressed existing Hospital at Home services and those that were being set up, for people with a range of conditions, such as stroke, pneumonia or following surgery. The studies used interviews or focus groups to explore the views of people involved in delivering or receiving Hospital at Home services. We assessed and summarised the findings from each of the studies. We identified important findings across the studies, and then rated how confident we were in each finding. This confidence (or trust) depended on, for example, how much information relating to a particular finding had been provided in the studies.

What did we find?

We found 52 studies that explored Hospital at Home services, including 31 Early Discharge, 16 Admission Avoidance and five combined Early Discharge and Admission Avoidance services. These studies conducted interviews or focus groups with 662 healthcare staff, 900 patients, 417 caregivers and eight health funders.

In total, we identified 12 main findings after assessing all the studies. We grouped these findings as: (1) development of stakeholder relationships and systems prior to implementation, (2) processes, resources and skills required for safe and effective delivery, (3) acceptability and caregiver impacts and (4) sustainability of services. We are confident in most of our findings, but we are less confident in a few findings, mainly due to the small numbers of studies and interviews with health funders contributing to the review finding.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

All except one of the studies came from high‐income countries, and so our findings may not apply to low‐ and middle‐income countries. Some studies did not report all the information that might be useful. For example, services’ staffing and role types were not always included.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

The evidence is up‐to‐date to November 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of qualitative findings.

| Summary of review finding | GRADE‐CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidencea | Explanation of GRADE CERQual assessment | Studies contributing to the review finding |

| Theme 1. Development of stakeholder relationships and systems prior to implementation of Hospital at Home | |||

| Finding 1. Service level staff suggested early stakeholder engagement, including partnerships with third party service providers, were required to implement Hospital at Home. This was critical for implementing new services, overcoming regulatory requirements, building trust and ensuring referrals. | High | Minor concerns about adequacy. No or very minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Brody 2019; Chouliara 2014; Dinesen 2007; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Hitch 2020; Kraut 2016; Lemelin 2007; Moule 2011; Sims 1997; Testa 2021 |

| Finding 2. For healthcare services planning to implement Hospital at Home, current systems need to integrate activity data and service costs. This allows healthcare services to collate total costs and savings to measure financial impact. This is important as policy makers, hospital executives and insurers from multiple‐payer settings require evidence about the financial impact of Hospital at Home to inform commissioning decisions. For multiple‐payer systems, financial impact and approval could be enhanced by including patients who contribute smaller financial benefits to the hospital if they are an inpatient. | Moderate | Moderate concerns about adequacy. Minor concerns about coherence. No or very minor concerns about methodological limitations and relevance. | Brody 2019; Chouliara 2014; Dismore 2019; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Moule 2011 |

| Theme 2. Processes, resources and skills required to safely and effectively implement Hospital at Home | |||

| Finding 1. Safety concerns were expressed by all stakeholders, such as for patients going home alone in regard to pain management and their mobility, and staff expressed concern for their own safety due to home hazards, patient‐related factors and ergonomics. Patients were reassured about their safety with access to staff (including via phone) and equipment for safe monitoring. Timely delivery of appropriate equipment in the home alleviated some staff concerns. | High | Minor concerns about adequacy. No or very minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Dean 2007; Dismore 2019; Dow 2007b; Dubois 2001; Fisher 2021; Ko 2023; Kraut 2016; Kylén 2021; Lemelin 2007; Levine 2021; Lou 2017; Manning 2016; Nordin 2015; Sims 1997; Udesen 2022; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2021; Wallis 2022; Wang 2012; Wilson 2002 |

| Finding 2. Identifying patients using eligibility criteria and clinical judgement was challenging for referrers in the acute setting, especially in the start‐up phase of implementation. Services developed criteria to maintain responsiveness and manage capacity, and conducted teaching sessions to help acute staff to refer patients to Hospital at Home. Some services had concerns when staff were working at low capacity (not enough referrals), if staff were seeing patients that were either too ill, or did not need the higher level of care required for Hospital at Home. | High | Minor concerns about adequacy. No or very minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Andrade 2013; Brody 2019; Chouliara 2014; Dismore 2019; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Kraut 2016; Lemelin 2007; Manning 2016; Moule 2011; Udesen 2022; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020 |

| Finding 3. Leadership and co‐ordination from key champions, lead clinicians with medical responsibility and clinical accountability, managers with operational responsibility and other leaders were essential to provide high‐quality care. Hospital at Home managers, directors or co‐ordinators were responsible for creating a positive staff environment, ensuring protected time for training and clinical supervision, and facilitating service improvements. | Moderate | Minor concerns about adequacy and coherence. No or very minor concerns about methodological limitations and relevance. | Barnard 2016; Brody 2019; Crilly 2012; Dow 2007a; Fisher 2021; Hitch 2020; Karacaoglu 2021; Leung 2016; Sims 1997; Testa 2021; Udesen 2022 |

| Finding 4. A multidisciplinary skilled workforce was required to implement Hospital at Home, with collaboration between teams and professionals (e.g. via team meetings) a core feature. However, maintaining responsiveness was important, and the absence of a waiting list for admission to Hospital at Home allowed a service to respond to the demand for hospital care. Building rapport with external partners was challenging, and allied health professionals noted difficulties with their professional line of reporting and supervision. Some teams were frustrated by a lack of resource allocation, others recognised that the service was better staffed than usual care. Teams were also challenged to meet intensity targets and address workforce shortages. Multiple strategies could enhance capacity and responsiveness, such as securing more funding, training family members, adopting new technologies and implementing telehealth appointments. However, this could affect the provision of patient‐centred care. | High | Minor concerns about coherence. No or very minor concerns about adequacy, methodological limitations and relevance. | Andrade 2013; Barnard 2016; Brody 2019; Cegarra‐Navarro 2010; Chevalier 2015; Chouliara 2014; Cunliffe 2004; Dean 2007; Dinesen 2007; Dow 2007a; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Hitch 2020; Karacaoglu 2021; Lemelin 2007; Moule 2011; O'Neill 2017; Papaioannou 2018; Rayner 2022; Sims 1997; Testa 2021; Udesen 2022; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; von Koch 2000 |

| Finding 5. Staff training, expansion of roles beyond usual scope of practice and rapid delivery of equipment or medical testing was essential to implement Hospital at Home. Expanding nurse roles increased capacity for acute medical care in the home and residential care. Expanding rehabilitation assistant roles increased capacity for rehabilitation in the home. The expansion of roles required appropriate governance structures and policy changes. | High | Minor concerns about coherence. No or very minor concerns about adequacy, methodological limitations and relevance. | Andrade 2013; Barnard 2016; Brody 2019; Cobley 2013; Crilly 2012; Cunliffe 2004; Dinesen 2007; Dismore 2019; Dubois 2001; Fisher 2021; Hitch 2020; Karacaoglu 2021; Lemelin 2007; Leung 2016; O'Neill 2017; Papaioannou 2018; Rayner 2022; Sims 1997; Testa 2021; Udesen 2022; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2021 |

| Finding 6. Effective communication between staff, patients and caregivers, including documentation and sharing tailored information with patients, was essential to provide efficient and effective care and reassure patients that quality of care is maintained in Hospital at Home. Problems with communication were commonly encountered for patients (e.g. patient information was not tailored), caregivers (e.g. limited opportunities to discuss management with clinicians) and staff (e.g. absence of a shared electronic medical record hampering the sharing of information about patients, efficiency of the service and continuity of care). | High | Minor concerns about coherence. No or very minor concerns about adequacy, methodological limitations and relevance. | Andrade 2013; Barnard 2016; Brody 2019; Cegarra‐Navarro 2010; Chevalier 2015; Chouliara 2014; Cobley 2013; Collins 2016; Crilly 2012; Cunliffe 2004; Dean 2007; Dinesen 2007; Dinesen 2008; Dismore 2019; Dubois 2001; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Jester 2003; Kimmel 2021; Ko 2023; Lemelin 2007; Leung 2016; Levine 2021; Mäkelä 2020; O'Neill 2017; Ranjbar 2015; Reid 2008; Rossinot 2019; Schofield 2006; Sims 1997; Testa 2021; Udesen 2021; Udesen 2022; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2021; von Koch 2000; Wallis 2022; Wang 2012 |

| Finding 7. Health professionals required skills in delivering person‐centred care, shared decision‐making and tailoring care to achieve patient goals and patient satisfaction. Some caregivers were frustrated about their lack of involvement in decision‐making and care planning. Patients valued equal interactions and partnerships with the staff, and their ability to cater for their needs, and valued staff focussing on helping family members. | High | No or very minor concerns about adequacy, methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Andrade 2013; Chouliara 2014; Clarke 2010; Cobley 2013; Collins 2016; Cunliffe 2004; Dinesen 2007; Dow 2007a; Dow 2007b; Dubois 2001; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Hitch 2020; Jester 2003; Karacaoglu 2021; Kimmel 2021; Ko 2023; Kylén 2021; Levine 2021; Lou 2017; Mäkelä 2020; Manning 2016; Nordin 2015; Papaioannou 2018; Ranjbar 2015; Reid 2008; Rossinot 2019; Schofield 2006; Udesen 2021; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2021; von Koch 2000; Wallis 2022; Wilson 2002 |

| Theme 3. Acceptance, perceived benefits and caregiver impacts from Hospital at Home | |||

| Finding 1. Patients, caregivers and service level staff believed Hospital at Home (including in residential care) was an appropriate alternative to hospital inpatient care, and facilitated optimal recovery and satisfaction with less risk of hospital‐acquired complications. Patients appreciated positive and competent staff who motivated them to reach their recovery goals. Sometimes the lack of caregiver support and 24‐hour supervision from hospital staff made some patients prefer to stay in hospital. | High | No or very minor concerns about adequacy, methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Andrade 2013; Barnard 2016; Cobley 2013; Cunliffe 2004; Dinesen 2008; Dow 2007a; Dow 2007b; Dubois 2001; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Hitch 2020; Karacaoglu 2021; Kimmel 2021; Ko 2023; Kraut 2016; Lemelin 2007; Levine 2021; Lou 2017; Mäkelä 2020; Moule 2011; Nordin 2015; Papaioannou 2018; Ranjbar 2015; Rayner 2022; Rossinot 2019; Sims 1997; Testa 2021; Udesen 2021; Udesen 2022; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Wallis 2022; Wilson 2002 |

| Finding 2. Caregivers were impacted by Hospital at Home. This included disruption to their normal routines, work, energy and sleep. There were reports of stress and anxiety related to feeling untrained to provide patient support and monitoring and a lack of formal recognition and access to information. Some caregivers and patients were concerned about their privacy at home and the impact on the patient/caregiver relationship from being involved with care. | High | No or very minor concerns about adequacy, methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Andrade 2013; Brody 2019; Cobley 2013; Dinesen 2008; Dismore 2019; Dow 2007b; Dubois 2001; Fisher 2021; Hitch 2020; Jester 2003; Kimmel 2021; Ko 2023; Levine 2021; Lou 2017; Mäkelä 2020; Manning 2016; Nordin 2015; Reid 2008; Rossinot 2019; Sims 1997; Udesen 2021; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2021; Wallis 2022; Wilson 2002 |

| Theme 4. Sustainability of Hospital at Home | |||

| Finding 1. Staff and patients expressed concern that without widespread implementation and expansion, the perceived benefits of Hospital at Home to patients and the healthcare system would be limited. Health system benefits included long‐term financial savings from avoiding unnecessary hospitalisation, bed closures or reduced length of stay, plus increased hospital capacity with reduced waiting times. However, some patients were sceptical that Hospital at Home was more about saving money, and in multiple‐payer settings costs incurred by patients was a key factor when admitting patients to Hospital at Home. Peer institution success with Hospital at Home increased executive enthusiasm for Hospital at Home. Hospital at Home could showcase a hospital’s innovation and help sustain staff recruitment. However, staff recruitment may be more challenging in rural settings as excessive driving can affect staff satisfaction. | High | Minor concerns about adequacy. No or very minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance and coherence. | Andrade 2013; Dow 2007b; Fisher 2021; Gorbenko 2023; Hitch 2020; Karacaoglu 2021; Ko 2023; Moule 2011; Papaioannou 2018; Rayner 2022; Sims 1997; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2020; Vaartio‐Rajalin 2021; Wallis 2022 |

aThe GRADE‐CERQual evidence profile for each finding is available in Appendix 1.

Background

Description of the topic

Two related 'Hospital at Home' services provide alternatives to traditional in‐hospital care: Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home. Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home avoids hospitalisation by providing acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home or usual place of residence for a limited time, for a condition that would otherwise require a hospital admission (Edgar 2024). Eligible patients are typically referred from an emergency department, an acute assessment unit or directly from ambulance services; they can also be referred by community physicians and specialists to receive active treatment from healthcare professionals in their homes. Early Discharge Hospital at Home involves supporting patients to go home earlier than usual to receive acute care or subacute care in their homes for a limited time period (Caplan 2012; Goncalves‐Bradley 2017). Eligible patients are typically referred from acute inpatient care and provided active treatment from healthcare professionals in their homes, and therefore spend less time in hospital. This is a service that is more embedded in health systems due to the long‐term focus on reducing hospital length of stay. While this service can also include home‐based End‐of‐life Care services, which support people to die at home rather than in hospital (Sheppard 2021), End‐of‐life Care is not a focus of this qualitative evidence synthesis.

A Cochrane review of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home included 20 randomised trials and 3100 participants with various conditions (e.g. older adults requiring admission to hospital following a stroke, with a diagnosis of dementia, or adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure) (Edgar 2024). Compared to inpatient care, the review found that Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home probably makes little or no difference to patients' self‐reported health status, risk of death or likelihood of hospital readmission (moderate‐certainty evidence), probably reduces the likelihood of living in long‐term residential care at six months' follow‐up (moderate‐certainty evidence), may improve patient satisfaction (low‐certainty evidence) and may reduce healthcare costs (low‐certainty evidence) (Edgar 2024).

A Cochrane review of Early Discharge Hospital at Home included 32 randomised trials and 4746 patients with findings reported for various health conditions (e.g. stroke survivors, patients following elective surgery, older patients with various medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017). Compared to inpatient care, the review found that Early Discharge Hospital at Home probably reduces length of stay forpeople recovering from a stroke (about seven days), people following elective surgery (about four days) and older people with a medical condition ranging from half a day to 20 days (moderate‐certainty evidence). The evidence also showed that these services probably make little or no difference to the risk of death for people recovering from a stroke or older people with a mix of medical conditions (moderate‐certainty evidence), may make little or no difference to the risk of hospital re‐admission for people recovering from a stroke or elective surgery (low‐certainty evidence), and may decrease the risk of living in long‐term residential care for people recovering from a stroke and older people with a mix of medical conditions(low‐certainty evidence). The review also found that Early Discharge Hospital at Home may make little or no difference to caregiver burden for people recovering from stroke or elective orthopaedic surgery (low‐certainty evidence) and may slightly improve patient satisfaction for people recovering from stroke or elective surgery (low‐certainty evidence); we do not know if these services reduce healthcare costs across the various conditions because the certainty of this evidence is very low (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017).

Outcomes from these two Cochrane intervention reviews suggest that Hospital at Home services may provide either superior or similar outcomes compared to inpatient care. However, these reviews did not address how to implement these services. While health systems around the world vary with respect to financing (e.g. multiple‐ or single‐payer systems), policy objectives for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services are likely to be similar as they are expected to reduce demand for inpatient hospital beds, reduce costs and conserve health outcomes. This review seeks to understand the factors influencing their implementation. Here we use the term implementation to describe both the process by which these models of care are introduced to health systems and hospitals by policy makers, healthcare providers and governments through policy, guidelines and financing; and also the process by which these models of care are introduced and integrated into clinical practice by clinical leads and health professionals, how patient groups are selected for the services and how the services are experienced by patients and their caregivers.

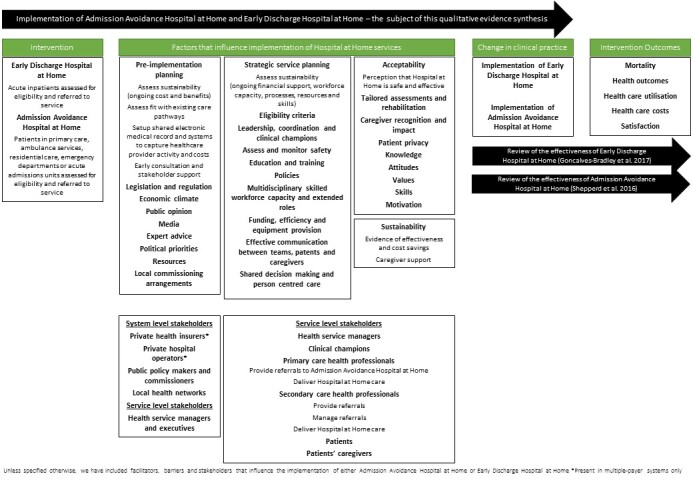

How the intervention might work

To integrate potential findings of this qualitative evidence synthesis with the two Cochrane intervention reviews, we have developed a logic model (Figure 1). The purpose of a logic model is to outline the hypothesised causal pathway that links the intervention (e.g. Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home for eligible patients) with mediating factors that impact on the key outcomes (e.g. health status, healthcare utilisation, patient and caregiver satisfaction, admission to long‐term residential care, as reported in the Cochrane intervention reviews) (Baxter 2014).

1.

Updated logic model describing the factors that influence implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home.

As a preliminary step we integrated the findings of qualitative studies known to the review team into the draft logic model to suggest potential mediating factors and key stakeholders at the system, service and stakeholder level that may influence implementation of Hospital at Home services (Brody 2019; Buhagiar 2017; Dismore 2019; Gardner 2003; Gardner 2019; Kraut 2016; Lemelin 2007; Mäkelä 2018). This logic model suggests that the key stakeholders for successful implementation vary in multiple‐payer systems and single‐payer systems at the system level (e.g. private health insurers and public policy makers) but hold similar positions at the service level (e.g. health service managers and health professionals in primary and secondary care). This logic model was updated after this qualitative evidence synthesis, and we invited members of our stakeholder advisory panel to review the findings to ensure we include interpretations from a broader lens in the development of the logic model.

Why is it important to do this synthesis?

Countries around the world are dealing with an increasing demand for hospital‐level care by introducing services that provide health care in the home, as an alternative to hospital admission. Virtual wards are one such service that gained traction during the COVID‐19 pandemic by providing remote monitoring to people in their home (Norman 2023). Hospital at Home that provides a higher level of care, for example Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home, is another service that expanded during the pandemic. Although there is a growing evidence base on the effectiveness and cost of these services (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Sheppard 2022; Edgar 2024; Singh 2022), health service planners and practitioners require evidence on how to implement and sustain these services on a wider scale.

There is also substantial variation in the implementation of Hospital at Home services across different countries and healthcare settings. Across England, a single‐payer system, healthcare providers have implemented three different types of Hospital at Home services, each with varying functions. This includes Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home, Early Discharge Hospital at Home and Discharge to Assess (services that provide short‐term, funded support for patients to be discharged to their own home or a community setting, where longer‐term support needs are assessed) (Young 2009). This variation makes it difficult to assess how Hospital at Home services contribute to health care and ease the demand for hospital‐based care (NHS Benchmarking Network 2015). In Australian public hospitals (a single‐payer system), hospital in the home multi‐day admissions ranged from 25 admissions in Tasmania in 2017 to 2018 to 30,070 admissions in Victoria in the same year (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019). Given the observed variation in implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home, and possibly variation in thresholds for admission to Hospital at Home across jurisdictions, there is a need to understand the factors that influence implementation of these models and how these may differ between healthcare settings (for example, high‐income versus low‐ and middle‐income countries; single‐payer systems versus multiple‐payer systems; urban versus regional or rural contexts; mechanisms of referral and boundaries with other health services; and the provision of social care and admission criteria). Where data permit, these factors will be explored in the qualitative evidence synthesis from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders.

A previous qualitative evidence synthesis including 16 studies examined perceptions of Hospital at Home among stakeholders with the main aim of identifying areas for improvement in this model of care (Chua 2022). Recommended improvements included more support for caregivers, including caregiver involvement in decision‐making, and better clinician training and use of technology to improve clinician collaboration and co‐ordination of Hospital at Home. Our qualitative evidence synthesis contributes new knowledge, as its focus is to explore factors affecting the implementation of these services, and it includes evidence for both acute and subacute care, applies GRADE CerQual to examine confidence in the findings, and applies rigorous Cochrane conduct and reporting methods including subgroup analyses. It also integrates with, and enhances, the findings of the two Cochrane intervention reviews (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024).

How this review might inform or supplement what is already known in this area

A qualitative exploration using a logic model to guide analysis facilitates the interpretation of the findings from the Cochrane intervention reviews by identifying the factors that hinder or support the implementation of these services. An assessment of the factors that influence the implementation of these services from the perspectives of people involved in the funding, commissioning and delivery of care (i.e. policy makers, managers, health professionals), and people receiving care (i.e. patients and caregivers), may also help to explain the reasons for variation in the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home in different healthcare settings.

This qualitative evidence synthesis takes a global perspective. The findings will assist the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home, and will be beneficial for a range of stakeholders, including policy makers and commissioners, health insurers, health service managers, health professionals, patients and patients' caregivers.

Objectives

To identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative research evidence on the factors that influence the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home, from the perspective of multiple stakeholders, including policy makers, health service managers, health professionals, patients and patients’ caregivers.

To explore how our synthesis findings relate to, and help to explain, the findings of the Cochrane intervention reviews of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services.

Methods

Design

This is a qualitative evidence synthesis of primary qualitative studies. Study reporting was guided by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) qualitative evidence synthesis template (Glenton 2020) and the 'enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research' (ENTREQ) guidance (Tong 2012).

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included primary studies that used qualitative methods for both data collection (such as focus group discussions or individual interviews) and data analysis (such as thematic analysis, framework analysis and grounded theory). We excluded studies that collected data using qualitative methods but did not analyse these data using qualitative analysis methods. As we expected to find sufficient qualitative studies that use qualitative methods for both data collection and data analysis, we excluded studies that collected data using open‐ended survey questions.

We included both published and unpublished studies, and studies published in any language. Mixed‐method studies were included where it was possible to extract the data that were collected and analysed using qualitative methods. We did not exclude studies based on our assessment of methodological limitations. We included studies regardless of whether they were conducted alongside studies of the effectiveness of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024).

Topic of interest

The qualitative evidence synthesis includes qualitative studies that examine the implementation of new or existing Hospital at Home services (Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home or Early Discharge Hospital at Home) from the perspective of different stakeholders. This will allow exploration of factors influencing the implementation of Hospital at Home services that are being introduced compared with services that are already in place. We use the term 'implementation' to describe both the process by which these models of care are introduced to health systems and hospitals through policies and guidelines, and also the process by which these models of care are put into clinical practice by clinical leads and teams of health professionals for appropriate patients and accepted by patients and patients’ caregivers.

To ensure the focus of this qualitative evidence synthesis matches the focus of the corresponding Cochrane intervention reviews, we have used similar definitions and exclusion criteria (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024).

Types of interventions

Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home is a service that is established to avoid hospitalisation. It provides acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home for a limited time, for a condition that would otherwise require a hospital admission (Edgar 2024). We included studies where patients are admitted to a Hospital at Home service from primary care in the community, ambulance services or from hospital emergency departments or acute admissions units.

Early Discharge Hospital at Home is a service that provides health care for patients discharged early from hospital. It provides acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home for a limited time, for a condition that would otherwise require a hospital admission (Deloitte Access Economics 2011; Goncalves‐Bradley 2017). We included studies where patients are admitted to this service following an early discharge from hospital. We considered early discharge as defined by the authors of included studies as there is no consistent definition; the length of hospital admission prior to early discharge varies by health condition and varies across trials (Deloitte Access Economics 2011).

We included studies about Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home, where health professionals provide active acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home or usual place of residence for a limited time and for a condition that would otherwise require a hospital admission. Typically, patients remain under the clinical responsibility of a hospital clinician while receiving Hospital at Home treatment, but we will also include studies where a patient’s general practitioner takes clinical responsibility. Health professionals that deliver Hospital at Home care can be hospital employees or employed through a service in the community (e.g. district nurses). For the purpose of this review, we define acute care as active, urgent, short‐term treatment in which the principal intent is to relieve symptoms of illness or injury, reduce the severity of an illness or injury, or protect against exacerbation or complication of an illness or injury that could threaten life or normal function (Independent Hospital Pricing Authority 2015; OECD 2011). We define subacute care as multidisciplinary care that is delivered by or informed by health professionals with specialist expertise and includes negotiated goals within a specified time frame that aim to optimise the patient’s functioning and quality of life (Independent Hospital Pricing Authority 2015; OECD 2011).

In line with these definitions, and with the exclusion criteria of the corresponding Cochrane intervention reviews, this review excluded studies that include patients not deemed to require acute or subacute care in a hospital setting. For example, we excluded from this review services that provide long‐term patient care, care in outpatient settings or after discharge from hospital, palliative care and self‐care by the patient in their home (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024). We additionally excluded studies that focus only on obstetric care, paediatric care, palliative care at home or mental health hospital at home (such as crisis‐resolution hospital at home) to ensure the focus of this qualitative evidence synthesis matches the focus of the corresponding Cochrane intervention reviews (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024). Studies that explore the implementation of Hospital at Home services for both adults (aged 18 years or older) and children will be included where data relating to adult Hospital at Home services are reported separately.

Types of participants

The review included the perspective of multiple stakeholders involved in Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home. Stakeholders' perspectives encompass their experiences, beliefs, perceptions and views relating to the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services.

At the system level, these stakeholders can include the following:

Policy makers and commissioners (or people in similar roles who make decisions about funding and policies for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home).

Private health insurers (or people in similar roles in multiple‐payer systems who make decisions about funding and policies for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home).

Private hospital operators (or people in multiple‐payer hospitals and hospital networks who make decisions about hospital policy and funding for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home).

Local health networks (or people in single‐payer hospitals and hospital networks) who make decisions about hospital policy and funding for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home.

At the service level, these stakeholders can include the following:

Health service managers (people in single‐payer or multiple‐payer hospitals who make decisions about policy and funding for patients’ care).

Clinical leads (health professionals who co‐ordinate and supervise teams of health professionals).

Clinical champions (health professionals who advocate for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home to help with successful implementation).

Primary care health professionals (health professionals in the community that provide referrals to Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home; health professionals in the community who deliver Hospital at Home care).

Secondary care health professionals (health professionals in the hospital emergency department that provide referrals to Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home; health professionals in the hospital that provide referrals to Early Discharge Hospital at Home; health professionals in the hospital that manage referrals to Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home; health professionals in the hospital that deliver Hospital at Home care).

Adult patients (aged 18 years and older) with a disease or condition requiring an acute or subacute hospital admission, who are eligible for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home or Early Discharge Hospital at Home. Patients requiring these services for the sole purpose of palliative care, obstetric care or mental health hospital at home are excluded from this review (see 'Types of interventions').

Patients’ caregivers (adults who would primarily provide assistance with activities of daily living, personal care and navigating services for the patient during the period of recovery) (Mäkelä 2020; Talley 2007).

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane EPOC Information Specialist developed the search strategy for this review in consultation with the review authors (Noyes 2020).

Electronic searches

To identify primary studies, we searched the following databases to 17 November 2022:

MEDLINE, Ovid

CINAHL, EbscoHOST

Scopus, Elsevier

Global Index Medicus, WHO

We did not apply limits to language or publication date. Our search strategy combined known terms for Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home with a qualitative filter. Terms related to Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home were derived from a 'gold set' of known qualitative papers that the author team knew would be included in the qualitative evidence synthesis, as well as all terms used in included papers in the Cochrane intervention reviews (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024), and terms currently used in real‐world practice and evaluations (HITH Society Australasia 2019; World Hospital At Home Congress 2019). Our strategy favours specificity over sensitivity (Harris 2018). The search strategies are detailed in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

Our search was supplemented by searching the reference list of relevant articles, and forward tracking the citations of studies included in the qualitative evidence synthesis and key references (the Cochrane intervention reviews and their included trials (Goncalves‐Bradley 2017; Edgar 2024)) using Scopus. Additionally, we approached experts in the field to request studies that might meet our inclusion criteria.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JH, JW) independently screened the title and abstract of all records obtained from searching the literature, and coded them as ‘retrieve’ (potentially eligible or unclear) or ‘do not retrieve’ (not eligible). Two review authors (JH, JW, PM in various combinations) independently screened the full text of all retrieved articles, identified studies for inclusion and recorded the reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. Any disagreement or uncertainty was resolved through discussion and, if needed, a third author (DOC, PM) adjudicated. Review authors who were authors on potentially eligible studies were not involved in assessing the eligibility of that study. Where necessary, we contacted study authors for further information.

We included a table listing studies that we excluded from our qualitative evidence synthesis at the full‐text stage, along with the main reasons for exclusion. Where the same study (i.e. using the same sample and methods) had been presented in different reports, we collated these reports so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in our qualitative evidence synthesis. Where the same Hospital at Home service was evaluated in different study reports (i.e. using different samples and methods), we considered these different studies, but noted that they assessed the implementation of the same service.

We used Covidence to screen and select studies, and we detailed the selection process to produce a Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram (Liberati 2009).

Language translation

We included reports in any language. For titles and abstracts published in a language other than English, we used open source software (Google Translate) to determine whether the paper was potentially eligible for inclusion. If potentially eligible, we translated the full‐text report into English using the same open source software and, if this translation was insufficient, we planned to ask members of Cochrane networks or other networks that are fluent in that language to assist in assessing the full text of the paper for inclusion. If we were still unsure about the study's eligibility, we planned to include these in 'Studies awaiting classification' to ensure transparency in the review process.

Sampling of studies

Qualitative evidence syntheses aim for variation in concepts rather than an exhaustive sample, and large amounts of study data can impair the quality of the analysis. Once we identified all studies that were eligible for inclusion, we planned to assess whether their number or data richness would likely represent a problem for the analysis and planned to consider selecting a sample of studies.

If sampling was required, we planned to use purposeful sampling, which aims to limit data redundancy while ensuring optimal data richness and diversity. We planned to stratify studies by intervention type (Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home or Early Discharge Hospital at Home). For each intervention, we planned to then use a sampling frame to ensure representation by stakeholder group level (system level, local level), and geographic area (urban and regional or rural; low‐ and middle‐income countries and high‐income countries). Where we observed the potential for data redundancy (for example, multiple studies of patients in urban, high‐income country settings), we planned to assess the data richness of each study using a pilot data richness scale (Appendix 3) (Ames 2017). We planned to only include studies that provided a good amount and depth of qualitative data pertaining to factors that influence implementation (data richness score greater than three) (Cochrane EPOC 2017).

For this review, we did not consider sampling a subset of studies was necessary.

Data extraction

Two review authors (ET, JH, JW in various combinations) independently extracted data on study characteristics, using a standardised data collection form developed for this qualitative evidence synthesis. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion or adjudication by a third author (PM). Review authors who were authors on an included study were not involved in data extraction for that study. For each study we recorded details, where available, on the following:

Intervention addressed (Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home; Early Discharge Hospital at Home) and whether the study is linked to an intervention trial.

Time since the intervention was implemented.

Study details (first author; corresponding author; year of evaluation; year of publication).

Research question and aims.

Geographic setting (country of programme; low‐ and middle‐income or high‐income country classification; urban, regional or rural location; multiple‐payer or single‐payer system; number of hospitals).

Participants (number; patient and caregiver characteristics (e.g. age, sex, clinical conditions), stakeholder's role or position (e.g. system level; private health insurer), service level (e.g. secondary care health professional)) and method of sampling participants.

Method of data collection (e.g. interview, focus group).

Method of data analysis (e.g. thematic analysis).

All text from the results sections of the included publications was extracted verbatim, including themes, sub‐themes, supporting quotes and conclusions (Thomas 2008).

To provide context for the qualitative findings, we used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework to extract information on the Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home or Early Discharge Hospital at Home intervention that was the focus of the qualitative study (Hoffmann 2014). Where required, we extracted this information from the qualitative study or from a linked effectiveness trial.

What (materials): were any informational materials used?

What (procedures): is there a programme manager and, if so, what is their role? What are the patient eligibility criteria? Who refers patients to the programme and what is the admission pathway? On average, how many days do patients spend in acute care before being transferred to Hospital at Home? Is acute or subacute care provided to patients in the Hospital at Home service?

Who provided: who are patients under the care of while enroled in Hospital at Home? Who delivers Hospital at Home care, and are they employed through the hospital or are they from the community? Was training provided to the health professionals that refer to Hospital at Home services or deliver Hospital at Home services?

How and where was the Hospital at Home intervention delivered (e.g. 1:1 face‐to‐face in patients’ homes)?

When and how much: on average, how many days do patients spend in Hospital at Home, and how often do they receive treatment by a Hospital at Home health professional? How long has the programme been running?

Tailoring: was the intervention tailored to specific hospitals, health professionals or patients or patient groups and, if so, how?

Modifications: was the intervention modified during the study?

How well (planned and actual): did the intervention employ any strategies to improve fidelity, and was fidelity achieved?

Assessing the methodological limitations of included studies

Two review authors (ET, JH, JW in various combinations) independently assessed the methodological limitations of each included study using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2020). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion or adjudication by a third author (DOC). The CASP tool uses a checklist of 10 questions, each of which includes multiple signalling questions to help users interpret the items (29 signalling questions in total). We summarised the findings of the CASP checklist in a 'Methodological limitations' table. Review authors who were authors on an included study were not involved in assessing the methodological limitations of that study.

Data analysis and synthesis

We used thematic synthesis to code the findings of included studies for factors that influence the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home or Early Discharge Hospital at Home according to stakeholder perspectives. For example: system level (private health insurer) and service level (patient, health professional, health service manager). We used the approach recommended by Thomas and Harden including inductive line‐by‐line coding of extracted text and development of descriptive findings (Thomas 2008).

We reviewed each line of extracted text and developed codes based on the content and meaning of each extract. Existing codes were reviewed and revised as new codes were added. When all studies had been coded, all text related to each code was reviewed for consistency of coding across studies. Two review authors (JW, ET) independently coded an initial subset of studies and then met to discuss any discrepancies until consensus was reached. The remaining studies were coded by one author (ET or JW) and verified by a second author (ET or JW). Review authors who were authors on an included study were not involved in data analysis for that study.

We reviewed all codes for similarities and differences, and organised them into descriptive themes and findings relating to the factors that influence the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services. One author (JW) drafted a summary of the descriptive findings and these were discussed by the review team until consensus was reached. We managed the analysis using NVivo 12 software (NVivo). We decided to complete the first two steps of the Thomas and Harden method of thematic synthesis to develop descriptive findings. Whilst it would have been an option to undertake stage 3 to develop analytical themes with new theoretical insights using synthesised data from included studies, Thomas and Harden suggest that movement to the development of new theory and theoretical insights (stage 3) can also be achieved when integrating the findings from the QES with the results of the intervention effectiveness reviews. We therefore further developed the initial logic model as the mechanism for developing new theoretical insights (see section 'Results of integrating the review findings with the Cochrane intervention reviews of Early Discharge Hospital at Home and Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home').

To maximise the likelihood that our findings are transferable to real‐world practice (Marshall 2014), we invited our stakeholder advisory panel to review the qualitative evidence synthesis findings and revised logic model (NHMRC 2017). Articulating our findings through a logic model facilitated communication of the findings to stakeholders and identified strategies to improve the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services (Harris 2018). GD, policy maker from NSW Health, provided this stakeholder feedback, which was incorporated into the discussion.

Once we finished preparing the qualitative evidence synthesis findings, we examined each finding, and developed prompts for future implementers. These prompts are presented in the 'Implications for practice' section. They are not intended to be recommendations but are phrased as questions to help implementers consider the implications of the review findings within their context (i.e. to what extent are identified factors that influence the implementation of Hospital at Home services addressed).

Subgroup analyses

Where data permitted, we examined similarities and differences in the factors that influence the implementation of Hospital at Home services with regard to the following study characteristics:

Type of delivery model (Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home versus Early Discharge Hospital at Home)

Geographic setting (high‐income versus low‐ and middle‐income countries; single‐payer systems versus multiple‐payer systems; urban versus regional or rural contexts; services delivered in people’s homes versus residential care)

Presence of intervention components (mechanisms of referral; the provision of social care; admission criteria)

Patient populations where there is evidence that Hospital at Home services are effective (e.g. older adults requiring hospital admission, such as for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; people recovering from stroke; people recovering from surgery), as informed by the Cochrane intervention reviews; patient populations identified as a priority for Hospital at Home services by policy makers

Assessment of confidence in review findings

Two review authors (JW, DOC) used the GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach to independently assess our confidence in each finding (Lewin 2018). CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence, based on the following four key components:

Methodological limitations of the included studies: the extent to which there are concerns about the design or conduct of the primary study that contributed evidence to an individual review finding

Coherence of the review finding: an assessment of how clear and cogent the fit is between the data from the primary studies and a review finding that synthesises those data (by 'cogent', we mean well‐supported or compelling)

Adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding: an overall determination of the degree of richness and quality of data supporting a review finding

Relevance of the included studies to the review question: the extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the review question

We rated each domain as no or very minor concerns, minor concerns, moderate concerns or serious concerns. After assessing each of these four components, we made a judgement about the overall confidence in the evidence supporting the review finding. We judged confidence as high (i.e. highly likely that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest), moderate (i.e. likely that the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest), low (i.e. possible that the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest) or very low (i.e. unclear whether the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest). All findings started as 'high confidence' and were graded down if there were important concerns regarding any of the CERQual components. Where concerns in relation to a component are minor or moderate, it may not be necessary to rate down. However, if there are a number of such concerns, it may be appropriate to rate down by one level to represent two or more of these concerns. The final assessment was based on consensus amongst the review authors.

'Summary of qualitative findings' table and evidence profile

We present a summary of the findings and our assessments of confidence in these findings in a 'Summary of qualitative findings' table and detailed descriptions of our confidence assessment in an evidence profile.

Integrating the review findings with the Cochrane intervention reviews

We organised the findings from our QES (Harden 2018) to reflect the timeline for planning and implementing Hospital at Home services, categorising factors as those that facilitate implementation and those that may limit effectiveness. The findings of the qualitative evidence synthesis may inform subgroup analyses for future updates of the Cochrane intervention reviews, as well as the design of future trials aiming to implement Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home services.

Review author reflexivity

All review team members have prior experience with Hospital at Home, or an awareness that Hospital at Home services have either superior or similar effects compared to inpatient care but are potentially under‐utilised. Hence, all team members tend to view these services favourably. We approached the review with an awareness of this bias towards positively viewing Hospital at Home services, and endeavoured to keep an open and curious mind about the factors that influence the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home.

We maintained a reflexive stance throughout all stages of this review process. All decisions or processes were conducted independently by at least two team members, who then discussed with each other and with the review team how their own backgrounds and positions may affect the analysis and interpretation of review findings. This allowed for regular opportunities to critically examine all decisions made and to counter our own biases. Members of this review team have clinical backgrounds (JW, DOC, RB, PM), qualitative research backgrounds (DOC, JW, SS, PM, RB), experience in writing Cochrane reviews (DOC, JW, JH, SS, RB) and experience in conducting research examining Hospital at Home (EG, JW, DOC, SS, PM, RB). Through our collective and individual experiences as clinicians, academics, researchers and policy makers, we anticipated that this review would reveal a combination of organisational, professional and individual factors that influence the implementation of Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home and Early Discharge Hospital at Home. As a team, we remained mindful of our presuppositions and supported each other to minimise the influence of these on our analysis or the interpretation of our findings. The lead author kept a reflexive journal throughout the review process and documented and reflected on progress and decisions made (Nowell 2017).

Results

Results of the search

We identified 7535 records through database searching up to 17 November 2022, plus one record via citation tracking. After 1688 duplicates were removed, we screened 5848 records, with 5656 records excluded based on titles and abstracts. We assessed 192 full‐text records for inclusion in this synthesis, with 123 records excluded due to incorrect study design (43 studies did not utilise qualitative methods in both data collection and analysis relating to service implementation) and incorrect intervention (80 studies were not assessing new or existing Hospital at Home services that were alternatives for acute or subacute care) (see Characteristics of excluded studies). In total, 52 studies (reported in 62 records) were included in the qualitative evidence synthesis, published from 1997 to 2022 and in three languages (English ‐ 49 studies, French ‐ two studies, Portuguese ‐ one study). Seven additional records are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification) (Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram

Description of the included studies

We included 52 studies in this review. A detailed description of the included studies is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. A description of intervention components is included in Table 2, separated by intervention types of Early Discharge Hospital at Home for acute care, Early Discharge Hospital at Home for subacute care, Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home, and combined Early Discharge and Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home.

1. TIDieR table.

| Study ID | What (materials) | What (procedures) | Who provided | How | When and how much | Tailoring/modifications |

| Were any informational materials used? |

What are the patient eligibility criteria? Who refers patients to the programme and what is the admission pathway? On average, how many days do patients spend in acute care before being transferred to Hospital at Home? |

Is there a programme manager and, if so, what is their role? Who are patients under the care of while enrolled in Hospital at Home? Who delivers Hospital at Home care, and are they employed through the hospital or are they from the community? Was training provided to the health professionals that refer to Hospital at Home services or deliver hospital at home services? |

How and where was Hospital at Home intervention delivered? (e.g. 1:1 face‐to‐face in patient's home) What was the communication process? Was a phone service available? |

On average, how many days do patients spend in Hospital at Home, and how often do they receive treatment from a Hospital at Home health professional? What is the discharge or readmission process? |

Was the intervention tailored to specific hospitals, health professionals or patients or patient groups and, if so, how? Was the intervention modified during the study? |

|

| Early discharge (acute care) | ||||||

| Chevalier 2015 | Service: 'Hospitalisation at Home' service linked to 1 hospital (urology surgery unit) Materials: no information |

Eligibility: urology surgery for prostate cancer. Not taking anticoagulant therapy; with an adenoma prostate less than 80 cc; residing in the territory covered by the service, accompanied by a loved one immediately following surgery to return home. Admission process: during the first urological consultation, the surgeon offers the patient the service. Patients who agree are registered by the urology secretary who emails information on patient to the HAH admission service. Average time to surgery is 15 days. A HAH nurse co‐ordinator had a telephone consultation with the patient 1 week before the surgery to plan the stay. Number of days in acute bed: zero (less than 12 hours in hospital), returns home on the day of surgery. |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: assume urology surgeon from hospital works in collaboration with the lead nurse co‐ordinators. Staff: nurses (including clinical lead nurse co‐ordinators), allied health professionals, social workers, assistant caregivers. All staff employed by the HAH service, which runs in collaboration with the hospital. Training: no information |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home. Nurses were given a protocol to follow for nursing interventions to ensure HAH is safe and effective for the patients. One example included a protocol for withdrawal of urinary catheter depending on the colour of the urine. Communication process: the patient has the option of calling the HAH service or urology service with 24‐hour number |

HAH length of stay: 2 days HAH visits: visited by a nurse on day 1 and day 2 Discharge process: nurse sends by fax a summary of the treatments carried out to the surgeon on day of discharge |

No information |

| Clarke 2010 | Service: 'Early supported discharge' service linked to 1 hospital's chest clinic Materials: no information |

Eligibility: acute exacerbation of COPD. Resident in the local borough. Admission process: referral to the programme by their respiratory consultant or nursing staff from hospital. Patients had to give informed consent to receive the service. Number of days in acute bed: the programme aimed for discharge to HAH after 3.5 days (the average length of stay for COPD in that hospital was 9.5 days). Participants in this study spent between 2 and 9 days in hospital. |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: no information Staff: 4 nurses with experience in respiratory care, based at a chest clinic attached to the acute care hospital. Training: no information |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home. Home visits involved clinical assessment and checking that medication was being taken appropriately. Communication process: no information |

HAH length of stay: up to 2 weeks HAH visits: patients were visited at home daily for 3 days and then, as required, up to 2 weeks Discharge process: no information |

No information |

| Collins 2016 | Service: 'Early supported discharge' service linked to 1 hospital Materials: no information |

Eligibility: no information Admission process: patients are given the option of early supported discharge in hospital by hospital staff Number of days in acute bed: no information |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: no information Staff: physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Unclear who they are employed under. Training: no information |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home Communication process: no information |

HAH length of stay: no information HAH visits: no information Discharge process: no information |

No information |

| Dean 2007 | Service: 'Early supported discharge Programme' linked to 1 hospital Materials: no information |

Eligibility: acute exacerbation of COPD Admission process: home care nurse in consult with physician may make the decision to admit. Nurses assess and educate patients suitable for supported discharge. Number of days in acute bed: no information |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: medical staff employed through hospital Staff: nursing employed through hospital. Community team (primary care). Training: no information |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home Communication process: no information |

HAH length of stay: 14 days HAH visits: no information Discharge process: discharged to primary care after 14 days |

No information |

| Dinesen 2007 | Service: 'Home hospitalisation' service linked to one hospital. Same service as in Dinesen 2008. Materials: no information |

Eligibility: patients with heart failure, arrythmia and patients up for medicine adjustment. Heart patients were typically past the acute phase of their condition. At the time the patients were selected for home hospitalisation, they were able to walk around without dyspnoea. Admission process: no information Number of days in acute bed: 3 days typically |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: cardiologist. Staff: home ‐ district nurses employed through community. Hospital ‐ nurses and doctors. Training: district nurses were trained in ECG recording and INR measurement techniques in order to carry out HAH duties |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home. Healthcare professionals at the hospital and district nurses enter data on blood pressure, pulse, weight and INR using a web‐portal to transmit patient data between home and hospital. When taking an ECG recording, district nurses also write a brief commentary about the patient's symptoms and transmit this information to the hospital. Communication process: the patients' GPs were informed by fax that their heart patient had been admitted to home hospitalisation. |

HAH length of stay: 3 days typically HAH visits: twice a day Discharge process: in case of emergency (anxiety, complications, etc.), the patient could at any time be re‐admitted to the hospital. Patients may also be instructed to return to the hospital after being assessed by their doctors or the visiting nurse. |

The design panel held a meeting to discuss the experiences and resolve the issues that occurred after the home hospitalisation of 3 patients. These issues included the adjustment and co‐ordination of workflows across sectors, comprehending written documentation by other healthcare professionals on the joint web‐portal as well as the difficulties on the part of the hospital staff to reach the district nurses on the phone. |

| Dinesen 2008 | Service: 'Home hospitalisation' service linked to 1 hospital. Same service as in Dinesen 2007. Materials: no information |

Eligibility: patients with heart failure, arrythmia and patients up for medicine adjustment. Heart patients were typically past the acute phase of their condition. At the time the patients were selected for home hospitalisation they were able to walk around without dyspnoea. Admission process: no information Number of days in acute bed: 3 days typically. (Of the 8 patients interviewed, average = 4.4 days, range 1 to 12.) |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: cardiologist Staff: home ‐ district nurses employed through community. Hospital ‐ nurses and doctors. Training: district nurses were trained in ECG recording and INR measurement techniques in order to carry out HAH duties. |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home. Healthcare professionals at the hospital and district nurses enter data on blood pressure, pulse, weight, and INR using a web‐portal to transmit patient data between home and hospital. When taking an ECG recording, district nurses also write a brief commentary about the patient's symptoms and transmit this information to the hospital. Communication process: the patients' GPs were informed by fax that their heart patient had been admitted to home hospitalisation. |

HAH length of stay: 3 days typically. (Of the 8 patients interviewed, average = 3.8 days, range 1 to 6.) HAH visits: twice a day Discharge process: in case of emergency (anxiety, complications, etc.), the patient could at any time be re‐admitted to the hospital. Patients may also be instructed to return to the hospital after being assessed by their doctors or the visiting nurse. |

The design panel held a meeting to discuss the experiences and resolve the issues that occurred after the home hospitalisation of 3 patients. These issues included the adjustment and co‐ordination of workflows across sectors, comprehending written documentation by other healthcare professionals on the joint web‐portal as well as the difficulties on the part of the hospital staff to reach the district nurses on the phone. |

| Dismore 2019 | Service: nurse‐led 'respiratory specialist service' linked to 3 hospitals Materials: no information |

Eligibility: COPD exacerbation admitted to hospital. Identified as low mortality risk using the Dyspnoea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidaemia and atrial Fibrillation (DECAF Score 0 to 1). Age 35 years or older. 10 or more smoking pack‐years. Pre‐existing or admission obstructive spirometry. Exclusion: illness (other than COPD) likely to limit survival to less than 1 year. On long‐term ventilation. Has a coexistent secondary diagnosis necessitating admission. Assessed more than one overnight stay after admission or could not provide written informed consent (for trial). Admission process: after a brief inpatient assessment, all patients who met the entry criteria were offered participation. Patients could return home immediately provided the initial arterial pH was 7.35 or more and PaCO2 was 6 kPa or less. Patients with PaCO2 greater than 6 kPa without acidaemia could return home after 1 overnight stay in hospital, provided they were not deteriorating. Patients with acidaemia could return home the day that followed resolution of the acidaemia and, if initiated, once non‐invasive ventilation was complete. Number of days in acute bed: usually transferred to HAH within 24 hours of admission |

Programme manager: unclear Medical responsibility: respiratory consultant (remotely) Staff: respiratory specialist nurse (clinical lead), physiotherapist, psychologist, occupational therapist, social care worker. All employed through hospital. Training: no information |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home.

Physiological parameters were monitored daily and blood sampling (including arterial blood gas analysis) taken as required. Oral and intravenous therapies, acute controlled oxygen therapy, physiotherapy, psychology, occupational therapy and formal social care were available at home. Communication process: an emergency contact number allowed patients to contact the team 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. |

HAH length of stay: median (IQR): 4 (2 to 5) days. HAH visits: once or twice daily by nurse under remote supervision of respiratory consultant. Unclear how often the other services are provided. Discharge process: the treatment period ended when the respiratory specialist nurse and consultant deemed that the patient was sufficiently well for discharge to the care of the GP. |

No information |

| Dubois 2001 | Service: 'Hospital‐at‐home care' service linked to 4 hospitals (urban and regional) Materials: care protocols developed by hospital physicians for each diagnosis and detailed the minimum care expected from the primary care physician and the home care team. E.g. frequency of home visits and monitoring. |

Eligibility: conditions: heart failure, community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) and proximal deep venous thrombosis (DVT), lower back pain, IV‐antibiotherapy (IV‐A), chronic leg ulcers, palliative care, oncology, hip replacement Exclusion: psychogeriatric disorders. Patients had to be admitted to one of the participating hospitals for 1 or 2 days to undergo a medical check‐up. Written consent to be treated at home from the patient and family. Admission process: referred by hospital and decision to partake in programme made by patients, informal caregivers/family and primary care physician. Number of days in acute bed: ranged between 1 and 9 days for CAP patients, 1 and 6 days for TVP patients, and 1 and 36 days for IV‐A patients. Only 6 patients were transferred to HAH care during the day of their hospital admission (Day 1), and two‐thirds of HAH care patients were at home at Day 2 or 3 (CAP 69%, DVT 68%, IV‐A 62%). |

Programme manager: no information Medical responsibility: primary care physicians are advised by a hospital physician and team and they work together Staff: nursing care and home help were provided under the responsibility of a nurse from the home care programme Training: no information |

HAH delivery: 1:1, face‐to‐face in the patient's home. Care protocols discussed between the hospital medical and nursing team and the health professionals directly involved in the care provided at the patients’ home. Communication process: no information |

HAH length of stay: 5 days average. Ranged 2 to 9 days for CAP, 1 to 18 days for IV‐A and 2 to 14 days for DVT. HAH visits: unclear how often they received treatment Discharge process: no information |

No information |

| Jester 2003 | Service: 'Hospital at home' linked to one specialist orthopaedic hospital Materials: no information |