Abstract

Previous research has shown that ocular dominance can be biased by prolonged attention to one eye. The ocular-opponency-neuron model of binocular rivalry has been proposed as a candidate account for this phenomenon. Yet direct neural evidence is still lacking. By manipulating the contrast of dichoptic testing gratings, here we measured the steady-state visually evoked potentials (SSVEPs) at the intermodulation frequencies to selectively track the activities of ocular-opponency-neurons before and after the “dichoptic-backward-movie” adaptation. One hour of adaptation caused a shift of perceptual and neural ocular dominance towards the unattended eye. More importantly, we found a decrease in the intermodulation SSVEP response after adaptation, which was significantly greater when high-contrast gratings were presented to the attended eye than when they were presented to the unattended eye. These results strongly support the view that the adaptation of ocular-opponency-neurons contributes to the ocular dominance plasticity induced by prolonged eye-based attention.

Keywords: Attention, Ocular dominance, Opponency neuron, Adaptation, Steady-state visually evoked potential

Introduction

Selective attention allows processing of the most salient or relevant information in the environment while ignoring other information [1, 2]. To date, a majority of attention research has mainly focused on the real-time effects of selective attention [3–10]. However, most recent studies [11, 12] have shown that prolonged attention to a monocular pathway (or eye-based attention) can change perceptual ocular dominance.

In the work of Song et al. [11], movie images were displayed normally to one eye of the participant (attended eye). Meanwhile, movie images of the same episode but played backwards were simultaneously presented to the other eye (unattended eye). Participants were requested to carry out a binocular rivalry task both prior to and subsequent to the movie presentation. Binocular rivalry is a type of perceptual bistability that arises when spatially overlapped but incompatible images (e.g., two small perpendicular gratings) are simultaneously presented to the two eyes. Usually, at any given time only the grating in one eye reaches awareness and remains visible for a while before the grating in the other eye competes for awareness. The ratio of dominance duration for each eye in the dynamics of binocular rivalry can offer an elaborate measure of ocular dominance [13]. After adapting to the “dichoptic-backward-movie” for an hour, the unattended eye, rather than the attended eye, increased its dominance in conscious perception during binocular rivalry. This reflected a shift of perceptual ocular dominance to the unattended eye. Notably, the perceptual boost of the unattended eye did not occur when test stimuli were binocularly compatible or when adapting stimuli involved little or no binocular rivalry, pointing to a potential role of interocular conflict in driving the effect [11]. However, more direct neural evidence is still lacking.

Modeling work on binocular rivalry has proposed that interocular conflict can be represented by ocular opponency neurons [14]. These conflict-sensitive neurons receive excitatory input from one eye and inhibitory input from the opposite eye. Not only that, these neurons are inactive unless the excitatory signals surpass the inhibitory signals. When activated, the opponency neurons also suppress the monocular neurons that send inhibitory signals to them (Fig. 1A).

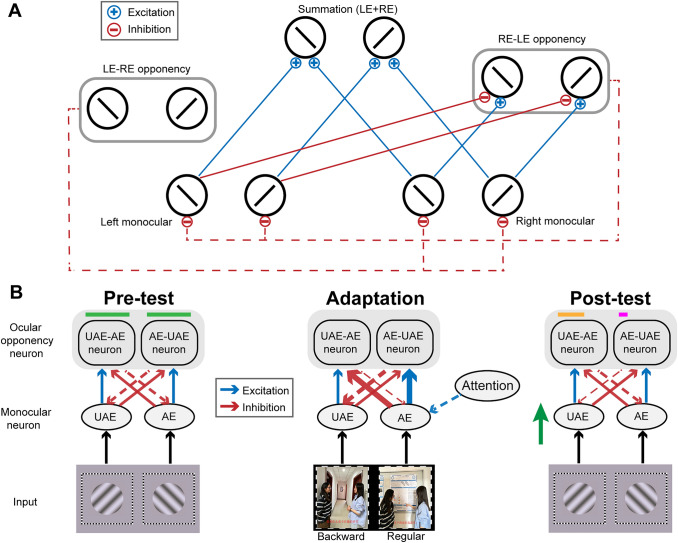

Fig. 1.

A Schematic of the ocular-opponency-neuron model [14]. The opponency neurons compute the difference of monocular input signals for a particular orientation preference and retinotopic location, and are activated only when the excitatory signals outweigh the inhibitory signals (solid blue lines for excitatory signals, solid red lines for inhibitory signals). When activated, the opponency neurons also suppress the monocular activity for the opposite eye (dashed red lines). To maintain brevity, the figure does not depict the excitatory and inhibitory inputs received by the left eye-right eye (LE-RE) opponency neuron. Abbreviations: LE, left eye; RE, right eye. B Simplified schematic of the mechanism of adaptation in ocular-opponency-neurons. The horizontal-colored lines depict the firing levels of ocular opponency neurons in the pre- and post-tests, with green/orange/magenta denoting relatively high/moderate/low intensity. Due to a greater extent of adaptation, the firing intensity of AE-UAE neurons decreases more than UAE-AE neurons, resulting in less inhibition of the signals from the unattended eye. Consequently, the ocular dominance shifts towards the unattended eye (green arrow). The black arrows indicate the transmission of visual signals. The solid blue or red arrows indicate the signal inputs from monocular neurons to the ocular opponency neurons. The dotted red or blue arrows indicate the modulation by the ocular opponency neurons or attention. The thickness of the arrow denotes the signal intensity. For simplicity, the orientation tuning information at the monocular processing stage has been omitted in this illustration. Abbreviations: AE, attended eye; UAE, unattended eye.

In line with the ocular-opponency-neuron model, a few reports have demonstrated the presence of opponency neurons in the visual cortex by measuring intermodulation steady-state visually evoked potential (SSVEP) responses [15, 16]. Intermodulation responses are known as binocular components (mf1 ± nf2, where m and n can be any non-zero integer) of the SSVEP in response to dichoptically presented visual stimuli flickering at different frequencies (f1 and f2). Katyal and colleagues [16] found that the intermodulation responses increase as a function of interocular conflict and weaken following adaption to interocular conflict. Their work thus sets a precedent for estimating the activity of ocular opponency neurons with the SSVEP technique.

Based on the ocular-opponency-neuron model [14] and the above evidence from Katyal and colleagues [15, 16], we aimed to seek more immediate neurophysiological evidence for the account [11] that the adaptation of opponency neurons contributes to the shift of ocular dominance induced by eye-based attention (Fig. 1B). To directly assess the response of opponency neurons before and after the “dichoptic-backward-movie” adaptation, we manipulated the contrast of testing gratings during the binocular rivalry task and relied on the intermodulation SSVEP response to track the activity of opponency neurons. Three conditions were included in each binocular rivalry test, determined by the contrast of the grating in each eye. The first was the “attended eye-unattended eye” (AE-UAE) condition, in which high-contrast gratings were presented to the attended eye and low-contrast gratings to the unattended eye. The second was the “unattended eye-attended eye” (UAE-AE) condition, with the unattended eye viewing the high-contrast gratings and the attended eye viewing the low-contrast gratings. Because a stimulus with higher contrast dominates conscious perception during binocular rivalry [17, 18], the AE-UAE opponency neurons, according to the model, would be activated for most of the time in the AE-UAE condition, making their activation the major source of the intermodulation response in this condition. By contrast, the UAE-AE opponency neurons would be activated most of the time in the UAE-AE condition. Thus, the intermodulation response in this condition would be dominated by the activation of the UAE-AE opponency neurons. The third condition was the iso-contrast condition, in which equally high-contrast gratings were presented to both eyes. This condition has been used to measure ocular dominance [19–22].

We predicted that during the “dichoptic-backward-movie” adaptation, the AE-UAE opponency neurons (which receive excitation from the attended eye and inhibition from the unattended eye) would adapt to a larger extent than the UAE-AE opponency neurons (which receive excitation from the unattended eye and inhibition from the attended eye) due to the prolonged top-down attention to the attended eye. Then the adaptation would result in a significantly greater reduction of the intermodulation response in the AE-UAE condition than in the UAE-AE condition.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Thirty-nine naive participants were recruited for the screening experiment (see Experimental Design below). Thirty-seven of them successfully passed the screening and subsequently participated in the formal experiment. Two participants failed binocular fusion in the post-test and another two were sick during the experiment. Accordingly, the data from 33 participants (15 females, aged from 18 to 29 years) were analyzed. We used G*Power [23] to estimate the minimum required sample size needed to detect a reliable effect in line with our hypothesis that dichoptic-backward-movie adaptation led to a greater reduction of intermodulation responses in the AE-UAE condition than in the UAE-AE condition. The estimation was based on data from the first 20 participants, in which we found a medium-sized effect (d = 0.51). Under the alpha level of 0.05, the effect size of 0.51, and the power level of 0.80, G*Power recommended a total sample size of 33 for the two-tailed paired-sample t-test. Therefore, we continued to collect usable data from 13 more participants. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and signed written informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Apparatus

The visual stimuli were programmed in MatLab (The MathWorks, Natick, USA) using the Psychtoolbox extensions [24, 25]. In the screening test, stimuli were presented on a 27-inch ASUS VG279QM LCD monitor (Asus, Shanghai, China, gamma-corrected, mean luminance: 30.18 cd/m2), while in the formal test, a 21.5-inch LEN LS2224A LCD monitor (Lenovo, Beijing, China) with gamma correction was used (mean luminance: 31.42 cd/m2). Both monitors refreshed at 60 Hz and had a spatial resolution of 1920 pixels × 1080 pixels. Participants viewed visual stimuli through a mirror stereoscope with their eyes 100 cm from the monitor. They were required to place their head on a chinrest to stabilize their position. The experiments were conducted in a dimly-lit room.

Stimuli and Procedure

Binocular Rivalry Test

Binocular rivalry stimuli consisted of two orthogonal sine-wave grating disks with a Michelson contrast of 80% or 20% (±45° from vertical, diameter: 6°). The gratings were presented dichoptically at the center of the visual field. A red central fixation point was on top of the grating, the diameter of which was 0.05°. To facilitate stable binocular fusion, the gratings were surrounded by a high-contrast checkerboard “frame” (size: 9° × 9°; 0.25° thick). The spatial frequency of the patches was 0.5 cycle per degree. The frequency tag technique was used to acquire the SSVEP signals for each eye during the binocular rivalry tests. The gratings presented to each eye were phase-reversed flickering [26]. The frequency of flickering was 3 Hz (f1) for the dominant eye and 3.75 Hz (f2) for the non-dominant eye (for the definition of eye dominance see Experimental Design below). This way of binding frequency to the eye is consistent with previous research [11, 15, 16, 27–33].

Each binocular rivalry test consisted of fifteen 1-min rivalry trials. Each trial began with a 5-s blank interval, followed by a 55-s presentation of the rival stimuli. During this time, participants were asked to report their perception of the stimuli by holding down one of the three keys (Right, Left, or Down arrow) to indicate whether they saw the grating as clockwise, counterclockwise, or a mix of both. The orientation and contrast of the gratings presented to each eye were kept constant within each trial, but randomly varied across the trials. The contrast of the gratings in each eye could be as follows: (1) 80% contrast in the dominant eye, 20% contrast in the non-dominant eye; (2) 20% contrast in the dominant eye, 80% contrast in the non-dominant eye; (3) 80% contrast in both eyes.

Dichoptic-Backward-Movie Adaptation

The “dichoptic-backward-movie” paradigm for the adaptation phase is also described in a previous report [11]. During one hour of adaptation, participants were shown dichoptically presented movie images (Fig. 2A), with the normal movie images played to one eye and the corresponding backward movie images played to the opposite eye. Of note, the backward movie was formally equivalent to the regular one with the exception of the absence of a logical movie plot. The frame rate of the movies was 30 frames per second. Participants were instructed that their main task was to exert their best effort to comprehend the logic of the normal movie, while disregarding the overlaid backward movie. As a result, we considered that top-down selective attention was primarily directed toward the normal movie. Here the eye that received the normal movie images was called the “attended eye”, while the other eye was called the “unattended eye”.

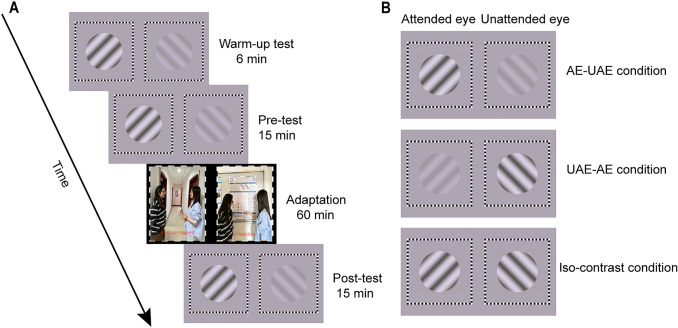

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the experimental paradigm and blob target stimulus in the adaptation phase. A The experimental paradigm known as the “dichoptic-backward-movie”. The red texts are the Chinese subtitles for the movie images. The figure is for demonstration purposes only. The actual movie images are not shown here because of copyright issues. B The blob target (see the gray region around the mouth in this example). This figure displays identifiable images of human faces solely for demonstration purposes. These images were captured from three students in our laboratory who have granted permission for their images to be published.

Blob Detection Task

The blob detection task has been described minutely in a previous report [11]. During adaptation, participants watched regular movies while also detecting a color desaturation within a blob region that was shown exclusively to one eye (Fig. 2B). To ensure that the blobs were always on a face in the movie, the locations of the blob targets were predetermined by the experimenter. Following the instruction, participants had to press the SPACE bar as soon as they detected any part of a character’s face turning gray.

To ensure that movie watching remained the main task, the presentation of the blob was infrequent, occurring only once per 5 min in each eye. To determine the timing of the blobs, the 1-h adaptation period was divided into 24 segments, each lasting 150 s. Twelve segments were randomly assigned to each eye. During the intermediate interval (50-s long) of a segment, a blob would fade within 0.2 s at a random moment. And after 5 s, it also faded out within 0.2 s.

Experimental Design

For the goal of preliminary screening, all participants were required to practice the binocular rivalry task for 3–7 days to ensure a stable performance of binocular rivalry prior to the formal experiment [34]. During this stage, the participants practiced three binocular rivalry tests per day, with a 10-min rest in between. Since perceptual eye dominance fluctuated greatly during the first few trials of a day [35], participants completed six warm-up trials before the practice of each day. The data collected during these warm-up trials were not analyzed. To clarify, the determination of perceptual eye dominance was based on the analysis of the data from the last three practice sessions. The eye that showed a longer summed phase duration was considered the dominant eye. For consistency between the practice and the formal tests, the gratings used in the binocular rivalry practice stage were also phase-reversed flickering. Two participants quit the study due to difficulties in binocular fusion.

Once the binocular-rivalry practice sessions were finished, participants took the second screening test in which they watched the dichoptic movie while performing the blob detection task [11]. The goal was to assess participants’ ability to allocate eye-based attention [36]. Only those who had demonstrated superior performance of blob detection in the attended eye or subjectively reported paying more attention to the regular movie images were qualified to proceed with the formal experiment. All the participants in this stage successfully passed the screening (hereafter M represents the mean, and SEM represents the standard error of the mean. Detection percentage: MAE = 0.55, SEMAE = 0.05; MUAE = 0.21, SEMUAE = 0.03).

The formal experiment began with two binocular rivalry tests (Fig. 3A). The first test was a warm-up test consisting of six trials, which were not analyzed [19, 34]. The second test, including 15 trials, was the binocular rivalry pre-test, which measured both the perceptual ocular dominance and SSVEP responses before adaptation. Following the pre-test, the participants underwent a 1-h dichoptic-backward-movie adaption. During adaptation, the main task was to comprehend the logic of the normal movie. The dichoptic movie was played with sound and the audio track always synchronized with the normal movie images to facilitate the allocation of eye-based attention. Based on the previous findings [11], the dominant eye always viewed the normal movie images (i.e., the dominant eye was always the attended eye) to maximize the shift of eye dominance. Concurrently, participants had to detect the occasional blob targets. Immediately after the adaptation, a 15-trial binocular rivalry test was performed as the post-test.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of (A) the process in the formal experiment and (B) the three test conditions. Abbreviations: AE, attended eye; UAE, unattended eye.

Three conditions were included in each binocular rivalry test, determined by the contrast of the grating in each eye (Fig. 3B). The first was the AE-UAE condition, in which high-contrast (80%) gratings were presented to the attended eye and low-contrast (20%) gratings were presented to the unattended eye. The second was the UAE-AE condition, with the unattended eye viewing the high-contrast gratings and the attended eye viewing the low-contrast gratings. Third, in the iso-contrast condition, high-contrast gratings were presented to both eyes. In the pre- and post-tests, each condition consisted of 5 trials. The order of conditions was counterbalanced across trials but kept the same in the pre- and post-tests.

EEG Data Acquisition

Continuous EEG data were acquired from a 64-channel Quick-Cap (Neuroscan Inc., El Paso, USA) using Ag/AgCl electrodes. The amplified signals were then recorded by means of a SynAmps RT amplifier (Neuroscan Inc.). The impedance of each electrode was kept below 5 kΩ, and referenced online to the left mastoid (M1). The EEG signals were sampled at 1,000 Hz, and filtered with a 0.05 to 100 Hz bandpass filter and a 50 Hz notch filter. Vertical and horizontal electrooculograms were recorded to monitor eye movements.

EEG Data Analysis

EEG Preprocessing

Off-line analysis was applied using customized MatLab codes and FieldTrip [37]. The M1, M2, and EOGs were first removed from the raw data. The EEG data were segmented according to the trial periods, and then resampled to 1,024 Hz followed by band-pass filtering from 0.5 to 30 Hz. To minimize common noise, a surface Laplacian spatial filter was implemented [38]. This involved subtracting the mean response of the closest four to eight electrodes from the signal of the central electrode.

Extraction of SSVEP Signals

To extract the power spectra, a fast Fourier transform was applied to the preprocessed data. In the response spectrum, we extracted the SSVEP signals at the fundamental frequencies 6 Hz (2f1) and 7.5 Hz (2f2), i.e., even harmonics of the flickering) which tagged the monocular neural activity for each eye and the SSVEP signal at the intermodulation frequencies which was considered to reflect the neural activity of interocular competition [14–16, 39, 40]. Consistent with prior research [28, 41–44], intermodulation responses were identified at 6.75 Hz (f1 + f2). The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was computed as the ratio of the power at the target frequency to the average power of the 20 surrounding frequency bins (10 on each side, excluding the immediately adjacent bin) [11, 31]. Fig. 4 shows the scalp topography of SNR.

Fig. 4.

Average topography for SNR at the fundamental frequencies (2f1 = 6 Hz and 2f2 = 7.5 Hz) and the intermodulation frequency (f1+f2 = 6.75 Hz). Despite the lower SNR of intermodulation responses compared to the fundamental responses, the topography consistently revealed activity in the occipital region.

An adaptive recursive least square filter [45] was used to calculate the SSVEP amplitude at the frequencies of interest (2f1, 2f2, and f1 + f2) using a 1-s sliding window [32]. The first 2 s of data were excluded from analysis to avoid the start-up transient. The remaining time-course was averaged to estimate the SSVEP amplitude in a given trial. Based on previous studies [28, 32], the SSVEP amplitudes for statistical analyses were averaged across the electrode OZ and five neighboring electrodes (POZ, O1, O2, CB1, and CB2).

Index Defining the Ocular Dominance

To quantify perceptual and neural eye dominance, we calculated the index of ocular dominance (ODI) on both the dynamics of binocular rivalry and the SSVEP amplitudes of the fundamental frequencies in the iso-contrast condition for the pre- and post-tests. The ODI was calculated using the following formula, with scores ranging from 0 (complete dominance of the attended eye) to 1 (complete dominance of the unattended eye). In all cases, the same formula was applied to psychophysical and EEG data.

For psychophysics, y represents the summed phase durations for the exclusive perception of the stimulus in the attended or unattended eye; for EEG, y represents the mean SSVEP amplitudes to stimuli in the attended or unattended eye.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were applied using MatLab and SPSS. To investigate the effects of “dichoptic-backward-movie” adaptation on ocular dominance, the paired-sample t-test was applied to compare the ODI between the pre-test and the post-test. For the blob detection test, the detection percentage was initially calculated and a paired-sample t-test was then applied to compare the detection percentage between the attended eye and the unattended eye conditions. Moreover, the intermodulation responses of the AE-UAE condition and the UAE-AE condition were compared across pre- and post-tests using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). A post hoc test was conducted by using a paired-sample t-test, and the resulting P-value was corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) method. All t-tests were two-tailed and an α value of 0.05 was used.

Results

Behavioral Results

Binocular Rivalry Test

The ODI became larger in the post-test (M = 0.479, SEM = 0.007) than in the pre-test (M = 0.457, SEM = 0.006; t(32) = 3.01, P = 0.005, d = 0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.007 0.037]), suggesting that dichoptic-backward-movie adaptation shifted the perceptual ocular dominance towards the unattended eye (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

The results for (A) the perceptual ocular dominance shift, (B) the blob detection, and (C) the neural ocular dominance shift (n = 33). The bars in A show the grand average perceptual ODI and in C show the grand average neural ODI. The bars in B show the grand average detection percentages of the two eyes in the formal experiment. The individual data are represented by gray lines. Error bars indicate the SEM. **P <0.01; ***P <0.001, paired-sample t-test. Abbreviations: AE, attended eye; UAE, unattended eye.

Blob Detection Test

The detection percentage was higher when the blob was presented to the attended eye (M = 0.83, SEM = 0.02) than to the unattended eye (M = 0.31, SEM = 0.05; t(32) = 11.40, P <0.001, d = 1.98, 95% CI = [0.43 0.62], Fig. 5B).

EEG Results

To assess the changes in neural ocular dominance, we applied a paired sample t-test to the neural ODI between the pre- and post-tests. The results showed that the neural ODI became larger in the post-test (M = 0.498, SEM = 0.004) than in the pre-test (M = 0.490, SEM = 0.004; t(32) = 4.88, P <0.001, d = 0.85, 95% CI = [0.005 0.011]), suggesting that adaptation shifted the neural ocular dominance towards the unattended eye (Fig. 5C).

To evaluate the response changes of opponency neurons, we then focused on the SSVEP signals at the intermodulation frequency in the AE-UAE condition and the UAE-AE condition. We applied a 2 (test phase: pre-test, post-test) × 2 (stimulus condition: AE-UAE condition, UAE-AE condition) repeated measures ANOVA on the average SSVEP amplitudes (Fig. 6). The results showed a significant main effect of test phase (F(1, 32) = 4.83, P = 0.035, η2 = 0.13), suggesting that the SSVEP amplitude in the pre-test (M = 0.44, SEM = 0.019) was greater than that in the post-test (M = 0.42, SEM = 0.021, 95% CI = [0.001 0.031]). More importantly, the interaction between the test phase and the stimulus condition was significant (F(1, 32) = 6.48, P = 0.016, η2 = 0.17). The post hoc test revealed that the SSVEP amplitudes in the pre-test (M = 0.437, SEM = 0.019) were greater than that in the post-test (M = 0.417, SEM = 0.020; t(32) = 2.79, P = 0.009, d = 0.49, 95% CI = [0.006 0.035], PFDR = 0.018) in the AE-UAE condition, whereas there was no significant difference of SSVEP amplitudes between the pre-test (M = 0.434, SEM = 0.020) and the post-test (M = 0.422, SEM = 0.021) in the UAE-AE condition (t(32) = 1.56, P = 0.129, d = 0.27, 95% CI = [−0.004 0.028]). The main effect of the stimulus condition was not significant (P = 0.514).

Fig. 6.

A The SSVEP amplitudes at the intermodulation frequency (n = 33). The bars show the grand average SSVEP amplitudes for each condition. AE-UAE means “attended eye-unattended eye” condition, and UAE-AE means “unattended eye-attended eye” condition. The individual data are represented by gray lines. Error bars indicate the SEM. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; n.s., P >0.05, repeated measures ANOVA followed by the post hoc of the paired-sample t-test; the resulting P-value was corrected for multiple comparisons using the FDR method. B The amplitudes differences between the pre- and post-test under the AE-UAE and the UAE-AE conditions. After adaptation, the attenuation of the amplitude in the AE-UAE condition was significantly greater than those in the UAE-AE condition.

The two-way interaction results support the view that the adaptation of opponency neurons contributes to the shift of ocular dominance when interocular competition occurs during adaptation.

Moreover, we investigated the relationship between the change in intermodulation response and ODI. We first computed the perceptual and neural ocular-dominance-plasticity index (ODPI) by subtracting the ODI for the pre-test from that for the post-test. Then, we computed the change of intermodulation response (d) in the AE-UAE condition by subtracting the SSVEP amplitude for the post-test from that for the pre-test. Neither the perceptual ODPI nor the neural ODPI correlated significantly with the change in intermodulation response (P >0.368). Moreover, we computed the discrepancy between the alterations of the intermodulation response in the AE-UAE and UAE-AE conditions, and normalized this difference using the equation . Similarly, neither the perceptual ODPI nor the neural ODPI correlated significantly with the discrepancy between the alterations of the intermodulation response (P >0.329).

Discussion

Attending to regular movie images in one eye for an hour caused a shift of perceptual and neural ocular dominance towards the unattended eye that instead viewed movie images played backward. More importantly, the SSVEP response at the intermodulation frequency (i.e., intermodulation response) in the AE-UAE condition decreased significantly after the adaptation, and the magnitude of the decrease was significantly greater than that for the UAE-AE condition. These results support the view that the adaptation of opponency neurons contributes to the shift of ocular dominance when interocular competition occurs during adaptation.

Reshaping adults’ ocular dominance has been demonstrated in numerous short-term monocular deprivation studies in which the input of basic visual information is blocked in one eye [19, 21, 22, 46–49]. Combined with more recent findings [11, 12], the present work again suggests that high-level cognitive processing like attention can modulate ocular dominance plasticity without introducing an imbalance of low-level inputs between the two eyes.

Furthermore, the present study, to our knowledge, for the first time provides evidence that eye-based attention can modulate neural ocular dominance. With binocularly fused testing stimuli, Song et al. [11] did not find a change in neural ocular dominance after exactly the same “dichoptic-backward-movie” adaptation [11]. A major difference between the two studies in measuring neural ocular dominance is that here we adopted binocular rivalry stimuli (which involved interocular competition) rather than binocularly compatible (or fused) stimuli, indicating that the ocular dominance shift induced by eye-based attention can only be detected when there is interocular competition during the test. Notably, as revealed by Song et al.’s third experiment [11], this after-effect was absent when the interocular conflict was substantially reduced during adaptation, indicating that attention must cooperate with binocular rivalry mechanisms to reshape ocular dominance. Therefore, it seems that binocular rivalry mechanisms play a key role in attention-induced ocular dominance plasticity.

To understand the role of binocular rivalry mechanisms during adaptation, we can borrow the ocular-opponency-neuron model of binocular rivalry [14]. During the adaptation phase, voluntary attention to the regular movie led to stronger activation of monocular neurons for the attended eye than those for the unattended eye. Since this occurred most of the time, the AE-UAE opponency neurons should fire most of the time and thus adapt to a larger extent than the UAE-AE opponency neurons, which would cause the monocular neurons for the unattended eye to receive less inhibition from the AE-UAE opponency neurons in the post-test as compared with the pre-test, leading to a shift of ocular dominance towards the unattended eye (Fig. 1B). Indeed, we found a shift of perceptual and neural ocular dominance towards the unattended eye after adaptation in the iso-contrast condition.

Also as expected, the intermodulation response in the AE-UAE condition decreased significantly after adaptation, a hallmark of adaptation of the AE-UAE opponency neurons. As for the UAE-AE condition, due to the fact that the UAE-AE opponency neurons were silent in most of the adaptation phase, there was no large difference in the activity of UAE-AE opponency neurons compared to the pre-test, resulting in no significant difference in the intermodulation response for the UAE-AE condition between pre- and post-tests. What is more, the change in intermodulation response following adaptation in the AE-UAE condition was significantly greater than that in the UAE-AE condition. This finding suggests that the AE-UAE opponency neurons adapted to a larger extent than the UAE-AE opponency neurons. These results suggest that the adaptation of opponency neurons may be responsible for the shift of ocular dominance led by prolonged eye-based attention. We did not find a linear relationship between the change of intermodulation response and ODI. The neural ODI was calculated from the SSVEP responses to monocular inputs, whereas the intermodulation responses result from the non-linear integration of binocular inputs [50]. Given the complexity of intermodulation responses, the two indices do not necessarily show a simple linear correlation.

Ocular opponency neurons have received attention in previous psychophysical studies, and their roles in binocular rivalry have been described in detail in the recent theoretical model of binocular rivalry [14–16, 39, 40]. Recently, Katyal et al. [15, 16] provided neurophysiological evidence for the existence of ocular opponency neurons and suggested that the activity of these neurons is associated with intermodulation responses. Considering that the present findings can be well explained with the ocular-opponency-neuron model, our work thus to some extent provides more neurophysiological evidence for the existence of such conflict-sensitive neurons. According to Katyal et al. [15, 16] and the topography in our data, these conflict-sensitive neurons likely reside in the early visual cortex (e.g., V1). Therefore, we reckon that in our “dichoptic-backward movie” adaptation paradigm, eye-based attention presumably modulates neural activity at the early stages of visual processing. Whether eye-based attention makes a similar contribution in the common monocular deprivation paradigms awaits future investigations.

An alternative account of our results is the homeostatic plasticity mechanism. The function of this mechanism is to stabilize neuronal activity and prevent the neuronal system from becoming hyperactive or hypoactive. To reach this goal, the mechanism moves the neuronal system back toward its baseline after a perturbation [51, 52]. In our case, the after-effect can be explained such that the visual system boosts the signals from the unattended eye to maintain the balance of the network’s excitability. However, this account cannot easily explain why the change of neural ocular dominance led by prolonged eye-based attention was found here using binocular rivalry testing stimuli, but was absent in the previous research using binocularly fused stimuli [11]. In contrast, a recent SSVEP study also using binocularly fused stimuli has successfully revealed a shift of neural ocular dominance after 2 h of monocular deprivation [31], which is in line with the homeostatic plasticity account. Therefore, the mechanisms underlying the “dichoptic-backward-movie” adaptation and monocular deprivation probably do not fully overlap; and the binocular rivalry mechanism described in the ocular-opponency-neuron model seems to be more suitable than the homeostatic plasticity mechanism in explaining the current findings.

The duration of adaptation in the present study was fixed at 1 h. Thus, an interesting open question is to explore the temporal dynamics of attention-induced changes in ocular dominance. Previous work has found that the strength and duration of after-effects increase as a power law of the adapting duration [53–55]. Therefore, longer dichoptic-backward-movie adaptation may lead to stronger and longer-lasting after-effects of the ocular opponency neurons. This will likely allow researchers to detect a more persistent effect of ocular dominance shift towards the unattended eye. Future work will provide a clearer answer to this question.

To conclude, our results support the view that the adaptation of ocular opponency neurons is responsible for (though not necessarily the only cause of) the shift of ocular dominance led by prolonged eye-based attention. The findings also lend strong support to the newly raised perspective that some types of short-term ocular dominance plasticity can be understood within the framework of the ocular-opponency-neuron model [11]. Future work will examine to what extent this opponency neuron mechanism may participate in producing the effects of more common short-term monocular deprivation [19, 21, 22, 46–49].

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the excellent work of the technical support staff at the Institutional Center for Shared Technologies and Facilities of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021ZD0203800) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871104 and 31830037).

Conflict of interest

The authors claim that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lili Lyu, Email: lllv@ion.ac.cn.

Min Bao, Email: baom@psych.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Treisman AM. Strategies and models of selective attention. Psychol Rev. 1969;76:282–299. doi: 10.1037/h0027242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe JM, Cave KR, Franzel SL. Guided search: An alternative to the feature integration model for visual search. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1989;15:419–433. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.15.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbetta M, Miezin FM, Dobmeyer S, Shulman GL, Petersen SE. Attentional modulation of neural processing of shape, color, and velocity in humans. Science. 1990;248:1556–1559. doi: 10.1126/science.2360050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He X, Liu W, Qin N, Lyu L, Dong X, Bao M. Performance-dependent reward hurts performance: The non-monotonic attentional load modulation on task-irrelevant distractor processing. Psychophysiology. 2021;58:e13920. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangun GR. Neural mechanisms of visual selective attention. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:4–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motter BC. Neural correlates of attentive selection for color or luminance in extrastriate area V4. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:2178–2189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02178.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rees G, Frith CD, Lavie N. Modulating irrelevant motion perception by varying attentional load in an unrelated task. Science. 1997;278:1616–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidnyánszky Z, Sohn W. Learning to suppress task-irrelevant visual stimuli with attention. Vision Res. 2005;45:677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Q, Hu W, Liu K, Bu X, Hu L, Li L, et al. Modulation of spike count correlations between macaque primary visual cortex neurons by difficulty of attentional task. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38:489–504. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00790-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu B, Wang X, Wang L, Qu Q, Zhang W, Wang B, et al. Attention field size alters patterns of population receptive fields in the early visual cortex. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38:205–208. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00789-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song F, Lyu L, Zhao J, Bao M. The role of eye-specific attention in ocular dominance plasticity. Cereb Cortex. 2023;33:983–996. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhac116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, McGraw P, Ledgeway T. Attentional eye selection modulates sensory eye dominance. Vision Res. 2021;188:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ooi TL, He ZJ. Sensory eye dominance: Relationship between eye and brain. Eye Brain. 2020;12:25–31. doi: 10.2147/EB.S176931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Said CP, Heeger DJ. A model of binocular rivalry and cross-orientation suppression. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1002991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katyal S, Engel SA, He B, He S. Neurons that detect interocular conflict during binocular rivalry revealed with EEG. J Vis. 2016;16:18. doi: 10.1167/16.3.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katyal S, Vergeer M, He S, He B, Engel SA. Conflict-sensitive neurons gate interocular suppression in human visual cortex. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1239. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19809-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittle P. Binocular rivalry and the contrast at contours. Q J Exp Psychol. 1965;17:217–226. doi: 10.1080/17470216508416435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollins M. The effect of contrast on the completeness of binocular rivalry suppression. Percept Psychophys. 1980;27:550–556. doi: 10.3758/bf03198684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai J, Dong X, He S, Bao M. Monocular deprivation of Fourier phase information boosts the deprived eye’s dominance during interocular competition but not interocular phase combination. Neuroscience. 2017;352:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finn AE, Baldwin AS, Reynaud A, Hess RF. Visual plasticity and exercise revisited: No evidence for a “cycling lane”. J Vis. 2019;19:21. doi: 10.1167/19.6.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HW, Kim CY, Blake R. Monocular perceptual deprivation from interocular suppression temporarily imbalances ocular dominance. Curr Biol. 2017;27:884–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lunghi C, Burr DC, Morrone C. Brief periods of monocular deprivation disrupt ocular balance in human adult visual cortex. Curr Biol. 2011;21:R538–R539. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brainard DH. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RJ, Norcia AM. A method for investigating binocular rivalry in real-time with the steady-state VEP. Vision Res. 1997;37:2401–2408. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chadnova E, Reynaud A, Clavagnier S, Hess RF. Latent binocular function in amblyopia. Vision Res. 2017;140:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu L, Deng S, Feng L, Yuan J, Chen Z, Yan J, et al. Effects of monocular perceptual learning on binocular visual processing in adolescent and adult amblyopia. iScience. 2020;23:100875. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou C, Nicholas SC, Verghese P. Contrast normalization accounts for binocular interactions in human striate and extra-striate visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2020;40:2753–2763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2043-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou C, Tyson TL, Uner IJ, Nicholas SC, Verghese P. Excitatory contribution to binocular interactions in human visual cortex is reduced in strabismic amblyopia. J Neurosci. 2021;41:8632–8643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0268-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyu L, He S, Jiang Y, Engel SA, Bao M. Natural-scene-based steady-state visual evoked potentials reveal effects of short-term monocular deprivation. Neuroscience. 2020;435:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang P, Jamison K, Engel S, He B, He S. Binocular rivalry requires visual attention. Neuron. 2011;71:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Baker DH, Simard M, Saint-Amour D, Hess RF. Short-term monocular patching boosts the patched eye’s response in visual cortex. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2015;33:381–387. doi: 10.3233/RNN-140472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bao M, Dong B, Liu L, Engel SA, Jiang Y. The best of both worlds: Adaptation during natural tasks produces long-lasting plasticity in perceptual ocular dominance. Psychol Sci. 2018;29:14–33. doi: 10.1177/0956797617728126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki S, Grabowecky M. Long-term speeding in perceptual switches mediated by attention-dependent plasticity in cortical visual processing. Neuron. 2007;56:741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neisser U, Becklen R. Selective looking: Attending to visually specified events. Cogn Psychol. 1975;7:480–494. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen JM. FieldTrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2011;2011:156869. doi: 10.1155/2011/156869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hjorth B. An on-line transformation of EEG scalp potentials into orthogonal source derivations. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1975;39:526–530. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(75)90056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May KA, Li Z, Hibbard PB. Perceived direction of motion determined by adaptation to static binocular images. Curr Biol. 2012;22:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poggio GF, Talbot WH. Mechanisms of static and dynamic stereopsis in foveal cortex of the rhesus monkey. J Physiol. 1981;315:469–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai Y, Mao Y, Ku Y, Chen J. Holistic integration in the processing of Chinese characters as revealed by electroencephalography frequency tagging. Perception. 2020;49:658–671. doi: 10.1177/0301006620929197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Govenlock S, Kliegl K, Sekuler A, Bennett P. Assessing the effect of aging on orientation selectivity of visual mechanisms with the steady state visually evoked potential. J Vis. 2010;8:424. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mersad K, Caristan C. Blending into the crowd: Electrophysiological evidence of gestalt perception of a human dyad. Neuropsychologia. 2021;160:107967. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.107967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan X, Chen J, Fu Y, Wu Y, Ku Y, Cao F. Orthographic deficits but typical visual perceptual processing in Chinese adults with reading disability. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.02.13.528424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang Y, Norcia AM. An adaptive filter for steady-state evoked responses. Electroencephalography And Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section. 1995;96:268–277. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(94)00309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen BN, Malavita M, Carter OL, McKendrick AM. Neuroplasticity in older adults revealed by temporary occlusion of one eye. Cortex. 2021;143:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramamurthy M, Blaser E. Assessing the kaleidoscope of monocular deprivation effects. J Vis. 2018;18:14. doi: 10.1167/18.13.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang M, McGraw P, Ledgeway T. Short-term monocular deprivation reduces inter-ocular suppression of the deprived eye. Vision Res. 2020;173:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou J, Clavagnier S, Hess RF. Short-term monocular deprivation strengthens the patched eye’s contribution to binocular combination. J Vis. 2013;13:12. doi: 10.1167/13.5.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon N, Hohwy J, Davidson MJ, van Boxtel JJA, Tsuchiya N. From intermodulation components to visual perception and cognition-a review. Neuroimage. 2019;199:480–494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turrigiano G. Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turrigiano GG. Homeostatic plasticity in neuronal networks: The more things change, the more they stay the same. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong X, Engel SA, Bao M. The time course of contrast adaptation measured with a new method: Detection of ramped contrast. Perception. 2014;43:427–437. doi: 10.1068/p7691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bao M, Engel SA. Distinct mechanism for long-term contrast adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5898–5903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113503109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenlee MW, Georgeson MA, Magnussen S, Harris JP. The time course of adaptation to spatial contrast. Vision Res. 1991;31:223–236. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90113-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]