Abstract

Background

Many urothelial bladder carcinoma (UBC) patients don’t respond to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy, possibly due to tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) suppressing lymphocyte immune response.

Methods

We conducted a meta-analysis on the predictive value of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in ICB response and investigated TANs’ role in UBC. We used RNA-sequencing, HALO spatial analysis, single-cell RNA-sequencing, and flow cytometry to study the impacts of TANs and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) on IDO1 expression. Animal experiments evaluated celecoxib’s efficacy in targeting PGE2 synthesis.

Results

Our analysis showed that higher TAN infiltration predicted worse outcomes in UBC patients receiving ICB therapy. Our research revealed that TANs promote IDO1 expression in cancer cells, resulting in immunosuppression. We also found that PGE2 synthesized by COX-2 in neutrophils played a key role in upregulating IDO1 in cancer cells. Animal experiments showed that targeting PGE2 synthesis in neutrophils with celecoxib enhanced the efficacy of ICB treatment.

Conclusions

TAN-secreted PGE2 upregulates IDO1, dampening T cell function in UBC. Celecoxib targeting of PGE2 synthesis represents a promising approach to enhance ICB efficacy in UBC.

Subject terms: Immunosurveillance, Bladder cancer

Introduction

Urothelial bladder carcinoma (UBC) is the 10th most frequent malignancy worldwide [1]. Recently, the treatment of UBC has led to the advent of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy that targets either PD-1 or PD-L1 [2]. Emerging evidence indicates that approximately 70% of patients still do not respond favorably to ICB monotherapy [3–5]. Therefore, elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the development of ICB nonresponse is urgently needed to propose new therapeutic strategies.

Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) is one of the hallmarks of cancer and is the basis for immune evasion. Emerging evidence suggests that tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) play a regulatory role in TME [6–8]. While there is broad clinical evidence regarding the role of T cells in mediating anti-tumor immunity and clinical outcomes in ICB therapy, the role of TANs is poorly characterized owing to their relatively short lifespan.

Although neutral staining was initially responsible for neutrophil identification, emerging evidence indicates that TANs in the TME are anything but neutral. Neutrophils in tumor-bearing hosts can either oppose or potentiate cancer progression [7–10]. Our previous study revealed that cancer cells can manipulate TANs and upregulate PD-L1 expression to impair T-cell function [11]. Additionally, high expression of interleukin-8 (IL-8), a chemoattractant for myeloid leukocytes and inducer of neutrophil degranulation, was reported to be associated with a poor response to ICB therapy [12]. However, some studies have identified TANs that exhibit anti-tumor functions, particularly in the early stages of cancer [13]. Until now, it has remained largely unclear how the interactions between TANs and other components in the TME participate in the development of poor efficacy of ICB therapy.

Metabolic reprogramming is another hallmark of cancer that allows cancer cells to survive, metastasize, proliferate, and evade immune responses [14]. While the study of cancer metabolism has primarily focused on how it alters T-cell function, recent studies suggest that TANs can also modulate their metabolism to support the tumor microenvironment. TANs can upregulate metabolic pathways, such as fatty acid and amino acid metabolism, to construct a tumor-supporting TME [15–19]. However, the mechanisms underlying these adaptations are not well understood. Two important research questions remain: what are the key metabolic alterations that promote tumor growth by TANs, and how can we precisely target them to inhibit tumor growth?

In this study, we validated the correlation between high TANs infiltration and poor response to ICB in UBC and explored the critical mechanism by which TANs promote immunosuppression by upregulating IDO1 expression in cancer cells. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) secreted from TANs mediates the upregulation of IDO1 expression through the PKC-GSK pathway. We developed a combination strategy involving celecoxib and ICB therapy, which could augment immunotherapy efficacy and maximize the anti-tumor response.

Methods and materials

Key resources and reagents used in this study were summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Other methods were summarized in the Supplementary Methods.

Cells

The human UBC cell line, T24, and murine UBC cell line, MB49, were obtained from the ATCC and Millipore, respectively, and cultured using standard protocols. Human lymphocytes and neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) using the Pan T Cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) and Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, respectively. Cell purity was confirmed, and all cells were mycoplasma-free.

Animals

C57BL/6J mice between 4 and 6 weeks old were purchased from Hunan Silaikejingda Experimental Animal Company Limited (Hunan, China) and maintained in a specific pathogen-free animal facility at the South China University of Technology (SCUT).

Animal experiments

MB49 cells (5 × 105) were inoculated subcutaneously into the mice for the subcutaneous tumorigenicity assay. The diameter of the tumors was measured every 3 days using a caliper. Tumor volumes (TVs) were calculated using the following formula: TV = 0.5 × L × W2, where L is the tumor length, and W is the tumor width.

Neutrophil depletion study

One day prior to cancer cell inoculation, mice were injected with either the anti-Ly6G antibody (clone 1A8, BioXCell, 400 μg, intraperitoneally) or the isotype IgG control (clone MOPC-21, BioXCell, 400 μg, intraperitoneally) every 3 days (Supplementary Fig. 2E).

Anti-PD-1 treatment study in IDO1-KO MB49 cell tumors

For the anti-PD-1 treatment study of IDO1 knockout (IDO1-KO) MB49 cell tumors, mice were subcutaneously inoculated with either 5× 105 IDO1-KO MB49 cells or wild-type cells. From the 6th day after cancer cell inoculation, mice were injected with either anti-PD-1 antibody (200 μg, intraperitoneally) or isotype IgG control (200 μg, intraperitoneally) every 3 days (Supplementary Fig. 3C).

IDO1 inhibition therapeutic study

For the IDO1 inhibition therapeutic study, mice were randomized into four groups from the 6th day after cancer cell inoculation: vehicle treatment, anti-PD-1 antibody (200 μg, intraperitoneally, every 3 days), indoximod (400 mg/kg, oral gavage, every 12 h), or a combination of indoximod and anti-PD-1 antibody.

Celecoxib therapeutic study

For the celecoxib therapeutic study, mice were randomized into four groups from the 6th day after cancer cell inoculation. The groups received either vehicle treatment, anti-PD-1 antibody (200 μg, intraperitoneally, every 3 days), celecoxib (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally, every 12 h), or a combination of celecoxib and anti-PD-1 antibody.

Flow cytometry for animal experiments

Tumor-bearing mice were euthanized at designated time points before the tumors were collected and stored in ice-cold 2% FBS. The collected tumors were then minced into 1–3 mm pieces using a scalpel before incubation with trypsin (cat# R001100, Gibco), collagenase I (cat# GC305013, Servicebio), collagenase II (cat# GC305014, Servicebio), collagenase IV (cat# GC305015, Servicebio), and DNase (cat# 1121MG010, Servicebio) for 1 h at 37 °C. The resulting tumor suspensions were then passed through a 40 mm cell strainer to remove any large bulk fragments before being washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Cells were surface stained for lymphocytes by incubating 1 × 106 cells in 50 µL ice-cold PBS with properly diluted and fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD45.2, and CD8. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with a fixation/permeabilization solution (cat# 554722, BD Biosciences) for 20 min, and washed again with BD Perm/Wash Buffer (cat# 554723, BD Biosciences) before granzyme B antibody staining. Neutrophil surface staining was performed by incubating 1 × 106 cells in 50 µL ice-cold PBS with properly diluted and fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD45.2, CD11b, Ly6G, and Ly6C. Cells were analyzed using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA) and CytExpert software (Beckman Coulter, USA).

3D cell culture

Cancer cells were mixed with matrigel matrix at a 1:2 volume ratio with complete culture media and plated in 48-well plates in droplets at a density of 1 × 104 cells/30 μl. After matrigel polymerization, complete medium was added, and cells were cultured at 37 °C. On the 10th day after seeding, human PBMCs from bladder cancer patients were added, and the cells were co-cultured for 2 days. 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) assays were performed using an EdU Assay/EdU Staining Proliferation Kit (cat# ab219801, Abcam).

CRISPR-Cas9-guided Ido1 knockout in MB49 cells

A single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting Ido1 was designed and inserted into the lentiCRISPR v2 plasmid. The constructed plasmids were stably transfected into MB49 cells to knock out Ido1. The gRNA sequence selected for Ido1 was CACCGCGTCAAGACCTGAAAGCATGTTT. Non-targeting gRNA were used as the negative control. All plasmid sequences were verified by sequencing. Flow cytometry was used to verify the knockout of IDO1 in MB49 cells following interferon-γ (IFN-γ) stimulation.

Neutrophils Stimulating Cancer Cells Assay

To investigate the effect of neutrophils on cancer cells, T24 bladder cancer cells (1 × 105) were stimulated with neutrophils (3 × 106) isolated from the peripheral blood of UBC patients. The neutrophils were removed the following day, and the cancer cells were washed with PBS and supplemented with fresh culture media. IDO1 expression in the cancer cells was analyzed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), flow cytometry, and western blotting.

Flow cytometry for in vitro experiments

Human lymphocyte surface staining was performed by incubating 2–5 × 105 cells in 50 μL of ice-cold PBS with properly diluted and fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD3 (clone OKT3, BioLegend), CD4 (clone RPA-T4, BioLegend), and CD8 (clone SK1, BD Biosciences). Antibodies were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. For IFN-γ staining, lymphocytes were fixed with fixation/permeabilization solution (cat # 554722, BD Biosciences) for 20 min. BD Perm/Wash™ Buffer (cat# 554723, BD Biosciences) was used to wash the cells and dilute the anti-IFN-γ antibody (clone B27, BioLegend) for staining. Tumor cells were fixed and stained with the anti-IDO1 antibody (clone V50-1886, BD Biosciences). The cells were then washed in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 200 μL of ice-cold PBS. Flow cytometry was performed using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA) and the results were analyzed using FlowJo (version 10).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were sliced into 4 μm sections. Sections were then blocked with goat serum for 10 min before incubation with primary antibodies against human IDO1 (1:400, clone D5J4E, Cell Signaling Technology (CST)), CD66b (1:1000, clone G10F5, BD), CD8 (1:400, clone D8A8Y, CST), mouse Ly6G (1:800, clone 87048S, CST), mouse CD8 (1:1000, clone 70306, CST), and mouse IDO1 (1:100, cat# 13268-1-AP, Proteintech). Following incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody, the sections were visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride with the Envision System (DAKO) and hematoxylin counterstain (BioSharp).

Multiplexed immunofluorescence

Multiplexed immunofluorescence (IF) was performed using the PANO Multiplex IHC Kit. Sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and incubated with primary antibodies against human IDO1 (1:3000, clone D5J4E, CST), cytokeratin (CK) (1:1000, clone AE1/AE3, CST), CD8 (1:2000, clone D8A8Y, CST), and CD66b (1:2000, clone G10F5, BD Biosciences). For mouse tissue analysis, a primary antibody against CD8 (1:1200, clone D8A8Y, CST) was used. After incubation with the secondary antibody, Opal working solution was added to generate an Opal signal. IF staining was performed using the Akoya Phenoptics Vectra Polaris System. Spatial infiltrations were quantified using the spatial analysis module of HALO (Indica Lab).

RNA-sequencing and in silico analysis

Bulk RNA-sequencing

We conducted a retrospective expression profiling analysis of 50 UBC tumor specimens obtained from Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital using high-throughput sequencing. Differentially expressed genes were screened using the DESeq2 R package with |log2FC| > 1 and False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05 as criteria. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to identify significantly enriched pathways between the two groups using the GSEA 4.1.0 desktop application.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing

Following the manufacturer’s guidelines, CD45+ immune cells were sorted using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from the tumor suspension stained with anti-mouse CD45.2 antibody. Droplet-based sequencing data from 10x Genomics were aligned and quantified against the GRCh38 human reference genome using Cell Ranger v3.0. The resulting filtered count matrix was used for downstream analysis in Seurat version 4.0.3. Cell filtering was performed using a normalized data function with a scaling factor of 10,000, and the top 2000 highly variable genes were selected using the Find variable feature function in the vst method. Batch effect was removed using the Mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) method. Clustering of cells was performed using the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions with 10 dimensions and a resolution of 0.8. Gene markers for each cluster were determined using the FindMarker function.

Statistical analysis

All experiments in the present study were independently performed three times. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SEM. The Mann-Whitney U test or chi-square (χ2) test was used for non-parametric variables, while Student’s t-test was used for parametric variables (two-tailed tests) to identify statistically significant data. The logrank test method was used to assess the survival. A meta-analysis was performed using Stata SE software. All other data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 9. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The infiltration of TANs and CD8+ T cells predicts UBCs’ response to immunotherapy

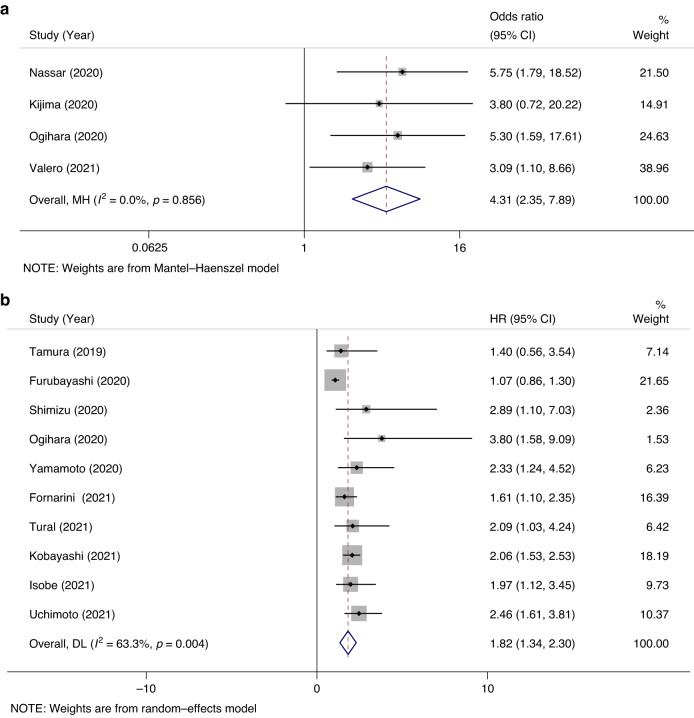

Emerging evidence shows that a higher neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with poorer patient outcomes in various cancers. To explore the predictive and prognostic value of baseline NLR in UBC patients receiving ICB therapy, we conducted a meta-analysis. Literature was reviewed [20–33]. Our analysis pooling data from multiple studies revealed that a high baseline NLR was significantly associated with ineffective outcomes of ICB treatment in UBC patients, with a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 4.31 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 2.35–7.89 (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, a higher baseline NLR was significantly associated with worse overall survival in UBC patients undergoing ICB therapy, with a pooled hazard ratio (HR) of 1.82 and a 95% CI of 1.34–2.30 (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Meta-analysis of the association between NLR and prognosis in UBC patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade therapies.

a, b Forest plots of association between neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio (NLR) and clinical response to immune checkpoint blockade therapies (a) and overall survival (b) in studies involving ICB treatment on UBC patients.

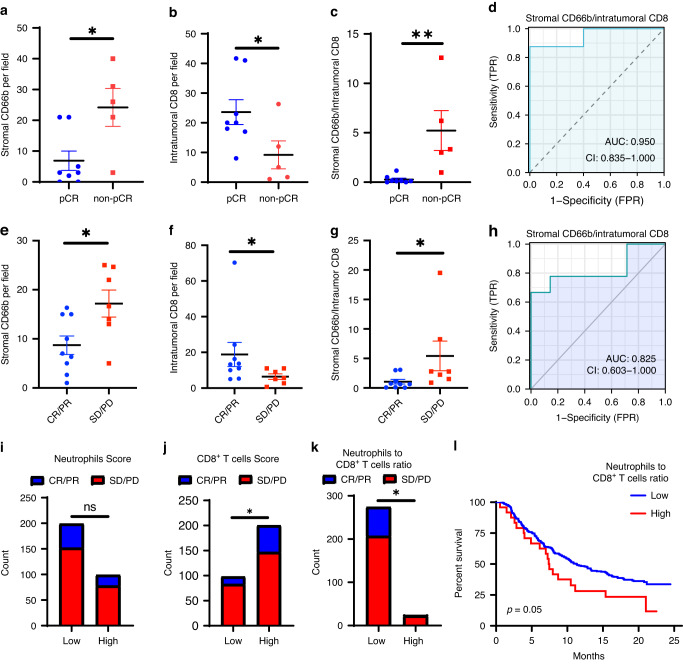

We performed immunohistochemical staining (IHC) analysis of CD66b and CD8 to assess the density of TANs and cytotoxic T cells in two cohorts of UBC patients undergoing ICB treatment. In the first cohort where patients received neoadjuvant ICB combined with chemotherapy, we found that TANs primarily infiltrated stromal regions, and stromal CD66b+ cell infiltration was significantly upregulated in the UBC tissues that did not achieve a pathologic complete response (pCR) following neoadjuvant treatment (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Intratumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration was higher in the UBC tissues that achieved a pCR following treatment (Fig. 2b). The stromal CD66b+/intratumoral CD8+ T cell ratio exhibited impressive predictive performance for the response to the therapy, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.950 (Fig. 2c, d). The intratumoral CD66b+/intratumoral CD8+ T cell ratio showed poor performance in predicting treatment response (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c), which may be due to the relatively low infiltration of CD66b+ cells within the tumor core.

Fig. 2. Neutrophil and CD8+ T cell infiltration predicts the response to immunotherapy in UBCs.

a–d Neoadjuvant ICB combined with chemotherapy cohort. e–h Adjuvant ICB cohort. i–l Reproduced results from IMVigor 210 database with CC 3.0 licence. a, b, c Dotplot showing the expression in IHC of stromal CD66b (a), intratumoral CD8 (b), or stromal CD66b to intratumoral CD8 ratio (c) in pCR or non-pCR patients. n = 8 in the pCR groups and n = 5 in the non-pCR group. d ROC curves represent the predictive value of stromal CD66b to intratumor CD8 score in pCR to neoadjuvant therapy. e, f, g Dotplot showing the expression in IHC of stromal CD66b (e), intratumoral CD8 (f), or stromal CD66b to intratumoral CD8 ratio (g) in patients CR/PR or SD/PD to ICBs. n = 9 in the CR/PR groups and n = 7 in the SD/PD group. h ROC curves represent the predictive value of stromal CD66b to intratumor CD8 score in ICB response. i, j, k Stacked bar plots showing the proportion of CR/PR or SD/PD patients in the IMVigor 210 cohort based on the score of neutrophils (i), CD8+ T cells (j), and neutrophils to CD8+ T cells ratio (k). For neutrophils or CD8+ T cells group classification, patients are divided into two groups according to the two-thirds number of neutrophils score (cut-off value = 2.442) and the one-thirds CD8+ T cells score (cut-off value = 0.1881). (i: n = 99 in the high group and 199 in the low group; j: n = 98 in the low group and 200 in the high group; k: n = 24 in the high group and 274 in the low group). l Kaplan-Meier plot displays the estimated overall survival probabilities of groups according to neutrophils to CD8+ T cells ratio (high: n = 24, Low: n = 274). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference, (Mann-Whitney rank test, Chi-square test, fisher exact test, or logrank test). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. pCR pathological complete response, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease.

The results from the second cohort of patients who received adjuvant ICB therapy were similar to those from the neoadjuvant cohort. The patients were grouped based on whether they achieved a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) to the treatment or had stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD). Stromal CD66b+ cell infiltration was elevated, and intratumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration was reduced in the SD/PD group (Fig. 2e, f, Supplementary Fig. 1d). The stromal CD66b+/intratumoral CD8+ T cell ratio differed between the two groups, and the ratio exhibited impressive predictive performance for the response to ICB therapy, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.825 (Fig. 2g, h). No difference in intratumoral CD66b+ cell infiltration was observed between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f).

We also used the TIMER to analyze immune cell infiltration in the IMvigor210 dataset [34]. We observed a trend that the group with high neutrophil levels contained fewer patients with CR/PR results, although there was no significant difference (21.21% vs 23.62%) (Fig. 2I). Additionally, the group with high CD8+ T cell infiltration had more patients with CR/PR (26.50% vs 15.31%) (Fig. 2j). Then patients with high neutrophils and low CD8 infiltration were defined as high NLR ratio patients. We found that 24.45% of low-ratio patients had a CR/PR to ICB therapy, whereas the rate was only 4.17% for patients with a high ratio (Fig. 2k). Furthermore, patients with a high ratio had shorter overall survival following ICB treatment (Fig. 2l).

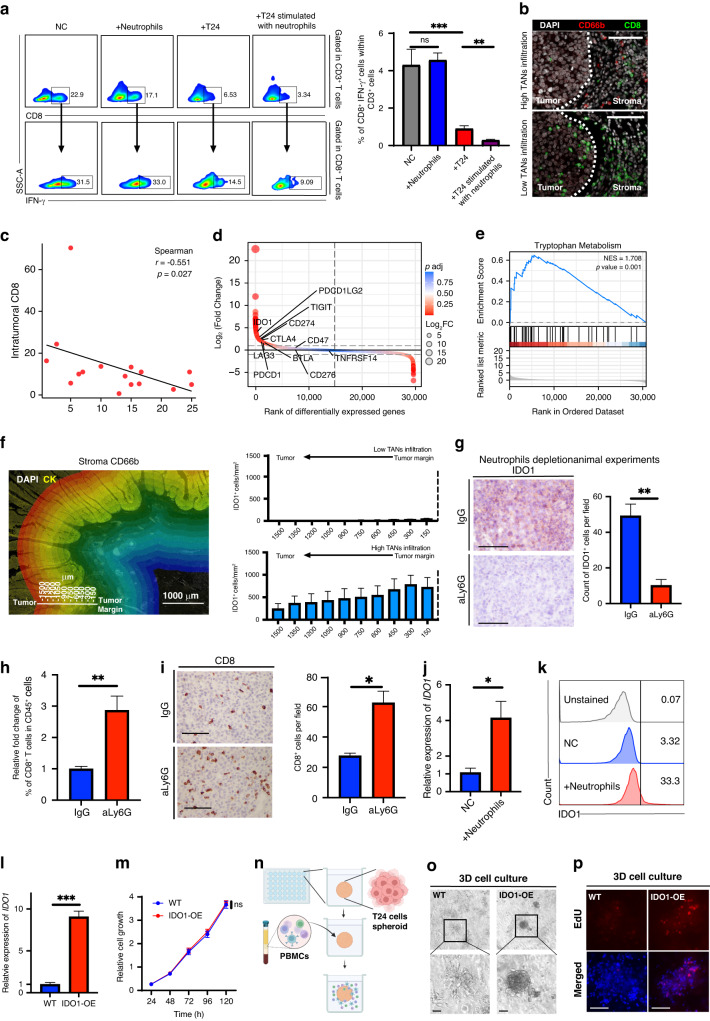

TANs suppress CD8+ T cells by interacting with cancer cells

To identify the mechanism responsible for TANs’ immunosuppressive effect in UBC, we conducted co-culture experiments involving neutrophils, T cells, and cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Neutrophils did not inhibit CD8+ T cell activation in co-culture with activated T cells (Fig. 3a). However, when co-cultured with T24 cancer cells, we observed a decrease in IFN-γ levels in CD8+ T cells compared to the control group. Importantly, when CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with T24 cancer cells previously stimulated with neutrophils, IFN-γ levels were significantly reduced, indicating that neutrophils maximize cancer cells’ immunosuppressive function to inhibit T-cell activation. Immunofluorescence staining showed that stromal CD66b+ cells were negatively correlated with intratumoral CD8+ cell density, suggesting that stromal neutrophils might indirectly suppress CD8+ T cells by facilitating an immunosuppressive TME (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Fig. 2b). There was no significant relationship between intratumoral CD66b+ cells and intratumoral CD8+ cells owing to the relatively low infiltration of TANs in the tumor core (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

Fig. 3. IDO1 mediates the immunosuppressive effects of the interaction between TANs and cancer cells.

a Flow cytometry analysis displays the proportion of IFN-γ+ T cells in the indicated groups, n = 4. b Representative images of intratumoral CD8+ T cells infiltration in the tumor core with or without abundant TANs surrounded. c Spearman correlation analysis of stroma CD66b count with intratumoral CD8 count. d Differential gene ranking plot displaying gene expression changes between tumors with high or low neutrophil infiltration, n = 25 in each group. e GSEA analysis showing the tryptophan metabolism pathway is enriched in tumors with high neutrophil infiltration. f Representative images illustrating methods of HALO immune infiltration analysis and analysis results of spatial distribution and expression intensity of IDO1 in relation to tumor margins with or without massive neutrophils surrounded, n = 5–6. g Representative images and statistical plot illustrating the expression of IDO1 in the indicated groups in the neutrophil depletion animal experiments, n = 4. h, i Flow cytometry (h), and IHC analysis (i) indicating CD8 infiltration in the indicated groups. j qRT-PCR result shows relative fold expression of IDO1 on T24 cells in the indicated groups, n = 4. k, Flow cytometry analysis shows IDO1 expression in tumor cells in the indicated groups. l qRT-PCR result shows relative fold expression of IDO1 on the WT and IDO1-OE T24 cells. m Cell viability results show the relative cell growth in the indicated groups, n = 4. n Representation of the 3D cell culture in 48 well plates and the infiltration of the PBMCs. o Representative images of the 3D cell culture models in the indicated groups. p Representative images of EdU assays in the 3D cell culture models models. Scale bar: black, 100 μm. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference, ns was no significance (one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests, unpaired Student’s t-test). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NC negative control.

IDO1 mediates the immunosuppressive effect of the interaction between TANs and cancer cells

To investigate the mechanism underlying the immunosuppressive effect of the interaction between TANs and cancer cells, we analyzed bulk RNA sequencing data of 50 UBC tumor samples. The samples were stratified into high or low TAN infiltration groups based on the degree of stromal CD66b infiltration. High TAN infiltration was associated with upregulation of IDO1 and enrichment of the tryptophan metabolism pathway (Fig. 3d). GSEA confirmed the enrichment of the tryptophan metabolism pathway in high-stromal TAN-infiltrated tumors (Fig. 3e).

We performed multicolor immunofluorescence on UBC tissues to investigate IDO1 expression and TAN distribution (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 2d). IDO1 was expressed mainly on the invasive tumor front, and its expression was significantly increased in tumors with abundant stromal neutrophils. We also examined IDO1 expression in neutrophil depletion animal experiments (Supplementary Fig. 2e–i). The results showed IDO1 expression was reduced in the neutrophil depletion group (Fig. 3g), and CD8+ T cell infiltration was elevated in this group (Fig. 3h, i). There was no significant difference in tumor size between the control and neutrophil-depleted groups, suggesting that neutrophil depletion might eliminate the anti-tumor effect of neutrophils. Therefore, even with an increase in CD8+ T cell infiltration, tumor growth did not slow down. Blocking the pro-tumor function of neutrophils is crucial for improving the immune microenvironment. An in vitro co-culture experiment followed by flow cytometry revealed that T24 cells’ IDO1 level was markedly upregulated after co-culturing with TANs (Fig. 3j, k). These data indicate the substantial functional relevance of the interactions between TANs and cancer cells.

To investigate the immune inhibitory function of IDO1, we constructed an IDO1-overexpressing (IDO1-OE) T24 cell line (Fig. 3l). In vitro cell viability experiments showed no significant differences in growth rates between IDO1-OE T24 cells and wild-type cells, indicating no apparent difference in proliferation between the two groups (Fig. 3m). We subsequently performed 3D co-culture experiments with cancer cells and PBMCs (Fig. 3n). However, the results showed that the morphology of IDO1-OE cell spheroid in the co-culture system was much more complete than that of the wild-type cell spheroid, indicating a weaker attack from immune cells in the IDO1-OE group (Fig. 3o). In addition, EdU assays also showed that the proliferation of IDO1-OE cancer cells in the co-culture system was significantly more active than that of the wild-type cells (Fig. 3p).

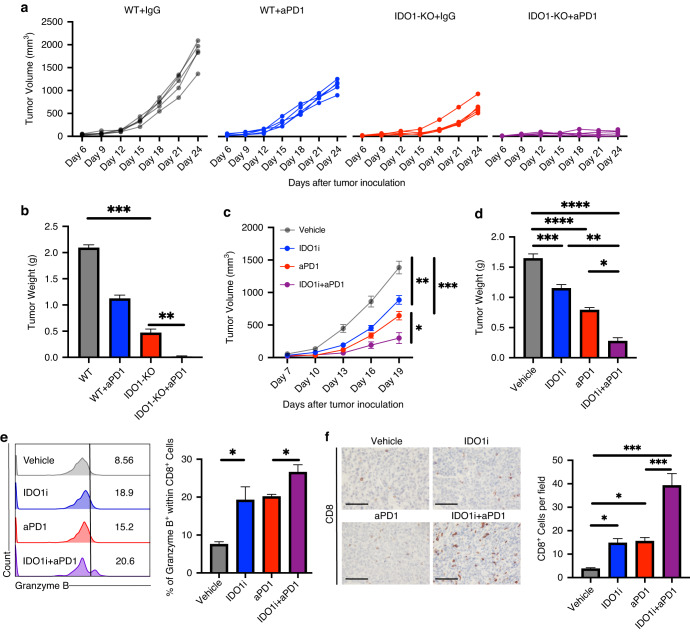

To examine whether targeting IDO1 could enhance ICB response in the TME, we generated a model of IDO1-KO MB49 cells using CRISPR-cas9. Flow cytometry results revealed a low level of IDO1 expression in the wild-type (WT) MB49 cell line, whereas incubation with IFN-γ upregulated IDO1 expression in WT cells, but not in IDO1-KO cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In animal experiments, IDO1-KO MB49 cells exhibited significantly inhibited tumor growth, and their tumor weights were significantly lower than those of the control group (Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Fig. 3c). Following anti-PD-1 treatment, ICB response was greatly enhanced in the IDO1-KO cell line, with 40% (2/5) of IDO1-KO tumors being eradicated after 2–3 doses of anti-PD-1 treatment.

Fig. 4. Combination treatment of IDO1 inhibition and anti-PD1 delays tumor growth.

a, b Tumor growth curves (a) and tumor weights (b) of wild type and IDO1-KO groups with or without anti-PD1 therapy were measured, n = 5. c, d Tumor growth curves (c) and tumor weights (d) of each group were measured following anti-PD1, indoximod, or a combination of indoximod and anti-PD1 treatment, n = 5. e Flow cytometry analysis of the proportion of Granzyme B+ cells within CD8+ T cells from the indicated groups, n = 3. f Representative images and statistical plot illustrating the expression of CD8 in the indicated groups, n = 4. Scale bar: black, 100 μm. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference, ns was no significance (one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test, unpaired parametric Student’s t-test). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. IDO1i: IDO1 inhibitor, indoximod; WT: wild type.

Combination treatment involving IDO1 inhibition and anti-PD-1 delays tumor growth

Treatment with an IDO1 inhibitor indoximod significantly delayed tumor growth in MB49 tumors. Combining indoximod and anti-PD-1 led to improved tumor growth delay (Fig. 4c, d). IDO1 inhibition increased infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, and the combination further increased infiltration (Fig. 4e, f). These results show that IDO1 inhibition can promote antitumor immunity and enhance the effects of PD-1 blockade therapy.

PGE2 secreted by TANs upregulates IDO1 via the PKC-GSK pathway

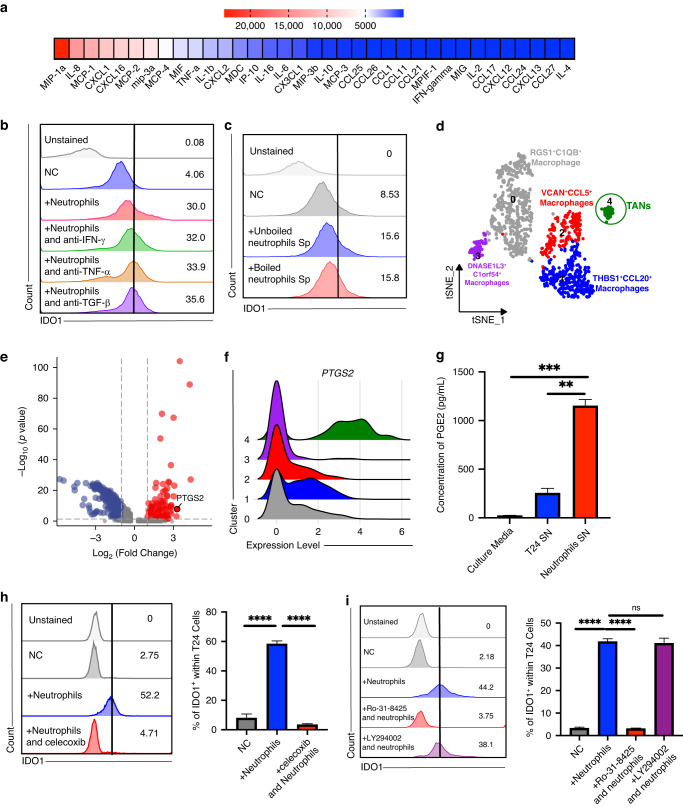

Based on the above findings, we explored the mechanism underlying the ability of TANs to upregulate IDO1 expression in cancer cells. We first conducted a cytokine assay to detect bioactive cytokines present in the TANs supernatant. However, Tumour Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) and IFN-γ, which were previously found to induce IDO1, were expressed at low levels in neutrophils (Fig. 5a) [35]. Neutralization of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) failed to reverse IDO1 upregulation in cancer cells (Fig. 5b). Boiled supernatant of neutrophils still upregulated IDO1 in T24 cells (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 4a), suggesting that proteins are not the dominant inducers of IDO1 expression. Other heat-tolerant factors, such as small-molecule metabolites, should be examined. Next, we performed scRNA-seq to explore TAN gene expression profiles. Myeloid cells was partitioned into five cell types, and neutrophils were annotated using CXCR2, CEACAM3, and CDA (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 4b) [36, 37]. We found that PTGS2, which encodes cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, was highly expressed in TANs, and ELISA results confirmed the neutrophil supernatant was rich in PGE2 (Fig. 5e–g). Moreover, prostaglandins are small molecular metabolites that are heat resistant. These results suggest that TANs secrete PGE2 to stimulate IDO1 expression in cancer cells. Next, we added celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, to block PGE2 synthesis in neutrophils, and flow cytometry showed that IDO1 expression did not increase in cancer cells following neutrophil stimulation (Fig. 5h).

Fig. 5. PGE2 secreted by neutrophils upregulated IDO1 via the PKC-GSK pathway.

a Multiple cytokines assay results indicate the relative concentration of cytokines and chemokines in the supernatant of peripheral neutrophils from UBC patients. b Flow cytometry analysis reveals that IDO1 expression in cancer cells cocultured with neutrophils following the indicated cytokines are targeted with corresponding antibodies. c Flow cytometry analysis displays IDO1 expression in cancer cells cocultured with unboiled or boiled neutrophils supernatant, n = 4-5. d tSNE plot of myeloid single cells from scRNA-seq colored by major cell types. e Volcano plot displays the differential expressed genes of neutrophils. f Ridgeplot shows expression levels of PTGS2 in the indicated clusters. g Histograms of ELISA results show the PGE2 concentration in the indicated groups, n = 6. h Flow cytometry analysis and statistical plot of IDO1 expression in cancer cells cocultured with neutrophils after celecoxib was treated, n = 3-5. i Flow cytometry analysis and statistical plot of IDO1 expression in cancer cells cocultured with neutrophils after Ro-31-8425, a PKC inhibitor, or LY294002 a pan-PI3K inhibitor, was treated, n = 5. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference, ns was no significance (one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. NC negative control.

Subsequently, we aimed to explore the mechanism underlying the ability of PGE2 secreted by TANs to upregulate IDO1 expression in cancer cells. We applied both a PI3K inhibitor and a PKC inhibitor to the co-culture system. Flow cytometry results indicated that the inhibition of PKC, but not PI3K, could reverse the ability of TANs to upregulate IDO1 (Fig. 5i). Western blotting analysis also showed that the expression of both p-GSK-3β and IDO1 increased in the co-culture group, and this effect could be attenuated by either celecoxib or a PKC inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). We also performed a signaling pathway phosphorylation microarray, and the results confirmed that GSK was significantly phosphorylated compared to the control (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

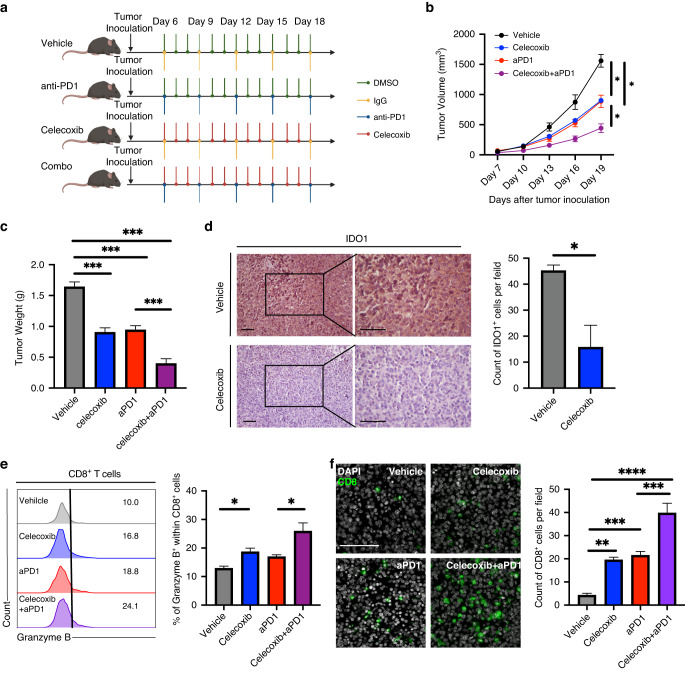

Celecoxib enhances the therapeutic activity of PD-1 blockade in combination therapy

These results suggest that celecoxib may increase the therapeutic efficacy of ICB treatment. To explore the effect of celecoxib combined with anti-PD-1 therapy, an MB49-tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mouse model was used (Fig. 6a). Celecoxib and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone significantly delayed tumor growth and prolonged the survival of tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 6b, c). Moreover, the combination of celecoxib and anti-PD-1 antibody enhanced the tumor growth control effect compared to that achieved using a single blockade. IHC results showed that IDO1 expression in the cancer cells was reduced following the celecoxib treatment (Fig. 6d). Flow cytometry and IF analysis indicated that, the combined targeting of PD-1 and celecoxib could achieve synergistic effects and promote a durable antitumor response (Fig. 6e, f).

Fig. 6. Celecoxib enhances the therapeutic activity of PD-1 blockade in combination therapy.

a Schematic representation of vehilce, celecoxib, anti-PD1, and combination treatment schedule. b, c Tumor growth curves (b) and tumor weights (c) of each group were measured after treatment with celecoxib, anti-PD1, or a combination of celecoxib and anti-PD1. d Representative images and statistic analysis illustrating the expression of IDO1 in the indicated groups. e Flow cytometry analysis of the proportion of Granzyme B+ cells within CD8+ T cells from the indicated groups. f Representative images and statistic analysis illustrating the expression of CD8 in the indicated groups. Scale bar: white, 100μm. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. n = 6 in (b, c); n = 3 in (d); n = 4–5 in (e); n = 5 in (f). p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference, (one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests, unpaired Student’s t-test). *p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Discussion

This study reveals the mechanism underlying ICB unsatisfactory response in UBC patients and provides evidence of TAN-mediated immune evasion, which activates the tryptophan metabolism pathway of cancer cells, contributing to the formation of an immunosuppressive TME. Our findings support the combinational use of ICB therapy and COX-2 inhibitors in UBC treatment, providing a rationale for preclinical testing.

Although the significant prognostic impact of TANs has been studied in various tumors, whether TANs are associated with a favorable or poor prognosis has been contradictory among different studies. More importantly, even though much evidence indicates that TANs play a vital role in promoting tumor progression, treatments that attempt to deplete TANs sometimes lead to disease progression [38–41]. The heterogeneity of TANs is thought to be the underlying mechanism of this outcome [42]. Fridlender et al. noted a difference in neutrophil polarization after treating mice bearing subcutaneous mesothelioma tumors with a TGF-β inhibitor. They subsequently proposed a binary classification system to distinguish tumor-inhibiting (N1) neutrophils from tumor-promoting (N2) neutrophils in a cancer setting [43]. Several studies have validated this finding [44–47]. Nevertheless, many researchers have argued that evidence defining these polarization states is still limited, and no definitive surface markers have been identified to distinguish N1 and N2 TANs [7, 48, 49]. Given that the pro-tumor subgroup of TANs remains difficult to define, targeting the pro-tumor aspects of TANs seems to be a more practical and realistic approach.

Previous studies have indicated that various pro-tumor mechanisms are utilized by TANs, ranging from inducing tumor invasion and growth to contributing to rapid vascular growth [50–53]. Recently, some studies have also indicated that TANs can affect T cell immunity by directly regulating T cells or indirectly modulating the TME [54]. We and others have previously shown that PD-L1+ TANs can bind PD-1+ lymphocytes in a cell-to-cell manner to assist immune evasion by cancer cells [11]. Accumulating evidence also suggests that TANs can dampen T cell function via chemokine, cytokine, or metabolite release. For instance, TANs may modulate the TME to undermine the host immune response by recruiting Treg cells and M2 macrophages [49, 55]. In this study, we found that TANs can reprogram lipid metabolism to synthesize prostaglandins, subsequently influencing amino acid metabolism in cancer cells to remodel an immunosuppressive TME.

Metabolic reprogramming is a dynamic feature of cancer progression. Our study establishes that UBC cells aberrantly utilize tryptophan metabolism to facilitate tumor growth and evade immune surveillance. Intriguingly, our results highlight the pivotal role of TANs in regulating tryptophan metabolism within the TME. Previous research has elucidated that IDO1 expression is modulated in response to diverse inflammatory stimuli, including IFN-γ, interleukin-1 (IL-1), and tumor necrosis factor [35]. Recently, fatty acid and prostaglandin metabolism in TANs has received increasing attention [19]. Our study demonstrated that the small-molecule metabolite PGE2, rather than cytokines secreted from TANs, is a powerful stimulus for IDO1. The role of PGE2 in TME has been extensively studied, and PGE2 is generally considered to possess potent tumor-promoting activity [56]. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. The direct role of PGE2 in tumorigenesis has been demonstrated in several animal models and in vitro. For example, one study suggested that the effect of PGE2 in increasing epithelial cell proliferation is mediated in part by the activation of the Ras-MAPK signaling cascade [57]. In this study, we discovered an indirect pro-tumor role of PGE2, which promotes IDO1 expression in cancer cells and undermines T cell function.

Although the pivotal role of IDO1 in cancer immune escape has been widely recognized, a recent phase III trial of the IDO1 inhibitor epacadostat failed [58]. Some have posited that the reason why the treatment efficacy is unsatisfactory is that selective IDO1 inhibitors used alone may involve an insufficient duration of effect and thus fail to activate an appropriate immune response. In vitro investigations have indicated that epacadostat functions as a substrate for efflux transporters in cancer cells [59]. Therefore, inhibiting the upregulation of IDO1 in cancer cells could be a promising solution, and one feasible approach is to block the upstream stimulator of IDO1 in the TME. Prior studies have suggested that the COX-2/PGE2 signaling pathway in cancer cells plays a crucial role in immunosuppression by hindering T cell infiltration, suppressing natural killer cell and dendritic cell maturation, and inducing macrophage polarization towards M2 maturation [60–64]. Clinical trials investigating COX-2 inhibitor combination therapies are underway. Our study demonstrates that PGE2 in the TME of UBC primarily arises from TANs and can activate the tryptophan pathway in cancer cells, suppressing T cell proliferation and activation. COX-2 blockade therapy can reprogram tryptophan metabolism and reactivate T cell-mediated immune responses.

Availability of data and materials

The data from the IMvigor210 cohort are freely available under the Creative Commons 3.0 license and can be downloaded from http://research-pub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies. Additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Conceptualization: YO, WZ, PX, and MY. Methodology: YO, LX, PX, LZ, HL, SL, XC, and JC. Software: YO, and YL. Formal Analysis: YO, WZ, PX, and BW. Investigation: YO, WZ, PX, DW, and ZO. Writing: YO, WZ, PX, and BW. Writing, Review & Editing: YO, WZ, TL, and JH. Visualization: YO. Funding Acquisition: TL, JH, and WZ. Resources: TL, JH, and WZ. Supervision: TL, JH, and CW.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFA0902803), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81825016, 81961128027, and 81902586), Key Areas Research and Development Program of Guangdong (Grant No. 2018B010109006).

Data availability

The data from the IMvigor210 cohort are freely available under the Creative Commons 3.0 license and can be downloaded from http://research-pub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies. The schematic and graphic illustration figure was created with BioRender.com.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All tissues and samples were obtained with written informed consent from patients involved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (approval number: SYSKY-2023-422-01). Animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the SCUT (approval number: 2022006).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yi Ouyang, Wenlong Zhong, Peiqi Xu, Bo Wang.

Contributor Information

Wenlong Zhong, Email: zhongwlong3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Chunhui Wang, Email: 13211604155@163.com.

Jian Huang, Email: huangj8@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Tianxin Lin, Email: lintx@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-023-02552-z.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powles T, Morrison L. Biomarker challenges for immune checkpoint inhibitors in urothelial carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:585–7. doi: 10.1038/s41585-018-0056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P, Retz M, Siefker-Radtke A, Baron A, Necchi A, Bedke J, et al. Nivolumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum therapy (CheckMate 275): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:312–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1909–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powles T, O’Donnell PH, Massard C, Arkenau HT, Friedlander TW, Hoimes CJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of durvalumab in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: updated results from a phase 1/2 open-label study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:e172411. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng LG, Ostuni R, Hidalgo A. Heterogeneity of neutrophils. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:255–65. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:431–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaul ME, Fridlender ZG. Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:601–20. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridlender ZG, Albelda SM. Tumor-associated neutrophils: friend or foe? Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:949–55. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolas-Avila JA, Adrover JM, Hidalgo A. Neutrophils in Homeostasis. Immun, Cancer Immun. 2017;46:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang M, Wang B, Hou W, Yu H, Zhou B, Zhong W, et al. Negative effects of stromal neutrophils on T cells reduce survival in resectable urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Front Immunol. 2022;13:827457. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.827457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuen KC, Liu LF, Gupta V, Madireddi S, Keerthivasan S, Li C, et al. High systemic and tumor-associated IL-8 correlates with reduced clinical benefit of PD-L1 blockade. Nat Med. 2020;26:693–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0860-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eruslanov EB, Bhojnagarwala PS, Quatromoni JG, Stephen TL, Ranganathan A, Deshpande C, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5466–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI77053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Reyes I, Chandel NS. Cancer metabolism: looking forward. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:669–80. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, Pearce EL. Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell. 2017;169:570–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodac A, Meylan E. Neutrophil metabolism in the cancer context. Semin Immunol. 2021;57:101583. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2021.101583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hossain F, Al-Khami AA, Wyczechowska D, Hernandez C, Zheng L, Reiss K, et al. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation modulates immunosuppressive functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and enhances cancer therapies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1236–47. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Udumula MP, Sakr S, Dar S, Alvero AB, Ali-Fehmi R, Abdulfatah E, et al. Ovarian cancer modulates the immunosuppressive function of CD11b(+)Gr1(+) myeloid cells via glutamine metabolism. Mol Metab. 2021;53:101272. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veglia F, Tyurin VA, Blasi M, De Leo A, Kossenkov AV, Donthireddy L, et al. Fatty acid transport protein 2 reprograms neutrophils in cancer. Nature. 2019;569:73–78. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furubayashi N, Kuroiwa K, Tokuda N, Tomoda T, Morokuma F, Hori Y, et al. Treating japanese patients with pembrolizumab for platinum-refractory advanced urothelial carcinoma in real-world clinical practice. J Clin Med Res. 2020;12:300–6. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fornarini G, Rebuzzi SE, Banna GL, Calabro F, Scandurra G, De Giorgi U, et al. Immune-inflammatory biomarkers as prognostic factors for immunotherapy in pretreated advanced urinary tract cancer patients: an analysis of the Italian SAUL cohort. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isobe T, Naiki T, Sugiyama Y, Naiki-Ito A, Nagai T, Etani T, et al. Chronological transition in outcome of second-line treatment in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer after pembrolizumab approval: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27:165–74. doi: 10.1007/s10147-021-02046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi T, Ito K, Kojima T, Maruyama S, Mukai S, Tsutsumi M, et al. Pre-pembrolizumab neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) predicts the efficacy of second-line pembrolizumab treatment in urothelial cancer regardless of the pre-chemo NLR. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022;71:461–71. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03000-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu T, Miyake M, Hori S, Ichikawa K, Omori C, Iemura Y, et al. Clinical impact of sarcopenia and inflammatory/nutritional markers in patients with unresectable metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ogihara K, Kikuchi E, Shigeta K, Okabe T, Hattori S, Yamashita R, et al. The pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a novel biomarker for predicting clinical responses to pembrolizumab in platinum-resistant metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients. Urol Oncol. 2020;38:602 e601–602 e610. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura D, Jinnouchi N, Abe M, Ikarashi D, Matsuura T, Kato R, et al. Prognostic outcomes and safety in patients treated with pembrolizumab for advanced urothelial carcinoma: experience in real-world clinical practice. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:899–905. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tural D, Olmez OF, Sumbul AT, Ozhan N, Cakar B, Kostek O, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have treated with Atezolizumab. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26:1506–13. doi: 10.1007/s10147-021-01936-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchimoto T, Komura K, Fukuokaya W, Kimura T, Takahashi K, Yano Y, et al. Risk classification for overall survival by the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and the number of metastatic sites in patients treated with pembrolizumab-a multicenter collaborative study in Japan. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Yamamoto Y, Yatsuda J, Shimokawa M, Fuji N, Aoki A, Sakano S, et al. Prognostic value of pre-treatment risk stratification and post-treatment neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio change for pembrolizumab in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26:169–77. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01784-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nassar AH, Mouw KW, Jegede O, Shinagare AB, Kim J, Liu CJ, et al. A model combining clinical and genomic factors to predict response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in advanced urothelial carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:555–63. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0686-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito K, Kobayashi T, Kojima T, Hikami K, Yamada T, Ogawa K, et al. Pembrolizumab for treating advanced urothelial carcinoma in patients with impaired performance status: Analysis of a Japanese nationwide cohort. Cancer Med. 2021;10:3188–96. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kijima T, Yamamoto H, Saito K, Kusuhara S, Yoshida S, Yokoyama M, et al. Early C-reactive protein kinetics predict survival of patients with advanced urothelial cancer treated with pembrolizumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70:657–65. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02709-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, Weiss K, Kelly DW, Adusumilli PS, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2021;12:729. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20935-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:W509–W514. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Platten M, Nollen EAA, Rohrig UF, Fallarino F, Opitz CA. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:379–401. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouillard AD, Gundersen GW, Fernandez NF, Wang Z, Monteiro CD, McDermott MG, et al. The harmonizome: a collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database (Oxford). 2016;2016:baw100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Frances A, Cordelier P. The emerging role of cytidine deaminase in human diseases: a new opportunity for therapy? Mol Ther. 2020;28:357–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Lago MA, Posner S, Thodima VJ, Molina AM, Motzer RJ, Chaganti RS. Neutrophil chemokines secreted by tumor cells mount a lung antimetastatic response during renal cell carcinoma progression. Oncogene. 2013;32:1752–60. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, O’Leary CE, Wang LS, Bhatti TR, Dai N, Kapoor V, et al. CD11b+Ly6G+ cells inhibit tumor growth by suppressing IL-17 production at early stages of tumorigenesis. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1061175. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1061175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costanzo-Garvey DL, Keeley T, Case AJ, Watson GF, Alsamraae M, Yu Y, et al. Neutrophils are mediators of metastatic prostate cancer progression in bone. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:1113–30. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02527-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Granot Z, Henke E, Comen EA, King TA, Norton L, Benezra R. Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:300–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sionov RV. Leveling up the controversial role of neutrophils in cancer: when the complexity becomes entangled. Cells. 2021;10:2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casbon AJ, Reynaud D, Park C, Khuc E, Gan DD, Schepers K, et al. Invasive breast cancer reprograms early myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow to generate immunosuppressive neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E566–575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424927112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pang Y, Gara SK, Achyut BR, Li Z, Yan HH, Day CP, et al. TGF-beta signaling in myeloid cells is required for tumor metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:936–51. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bodogai M, Moritoh K, Lee-Chang C, Hollander CM, Sherman-Baust CA, Wersto RP, et al. Immunosuppressive and prometastatic functions of myeloid-derived suppressive cells rely upon education from tumor-associated B cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3456–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Batlle E, Massague J. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity. 2019;50:924–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Qiu L, Li Z, Wang XY, Yi H. Understanding the multifaceted role of neutrophils in cancer and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2456. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giese MA, Hind LE, Huttenlocher A. Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2019;133:2159–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-844548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charles KA, Kulbe H, Soper R, Escorcio-Correia M, Lawrence T, Schultheis A, et al. The tumor-promoting actions of TNF-alpha involve TNFR1 and IL-17 in ovarian cancer in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3011–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI39065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanahan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12493–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gong L, Cumpian AM, Caetano MS, Ochoa CE, De la Garza MM, Lapid DJ, et al. Promoting effect of neutrophils on lung tumorigenesis is mediated by CXCR2 and neutrophil elastase. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:154. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spicer JD, McDonald B, Cools-Lartigue JJ, Chow SC, Giannias B, Kubes P, et al. Neutrophils promote liver metastasis via Mac-1-mediated interactions with circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3919–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–31. doi: 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mishalian I, Bayuh R, Eruslanov E, Michaeli J, Levy L, Zolotarov L, et al. Neutrophils recruit regulatory T-cells into tumors via secretion of CCL17-a new mechanism of impaired antitumor immunity. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1178–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakanishi M, Rosenberg DW. Multifaceted roles of PGE2 in inflammation and cancer. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:123–37. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang D, Buchanan FG, Wang H, Dey SK, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 enhances intestinal adenoma growth via activation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1822–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Long GV, Dummer R, Hamid O, Gajewski TF, Caglevic C, Dalle S, et al. Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus placebo plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma (ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1083–97. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Boer J, Shi JG, Hu P, Diamond S, et al. In vitro interactions of epacadostat and its major metabolites with human efflux and uptake transporters: implications for pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2017;45:612–23. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.074609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang D, Cabalag CS, Clemons NJ, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenases and prostaglandins in tumor immunology and microenvironment of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1813–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang MZ, Yao B, Wang Y, Yang S, Wang S, Fan X, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 in hematopoietic cells results in salt-sensitive hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4281–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI81550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zelenay S, van der Veen AG, Bottcher JP, Snelgrove KJ, Rogers N, Acton SE, et al. Cyclooxygenase-dependent tumor growth through evasion of immunity. Cell. 2015;162:1257–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holt D, Ma X, Kundu N, Fulton A. Prostaglandin E(2) (PGE (2)) suppresses natural killer cell function primarily through the PGE(2) receptor EP4. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1577–86. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang J, Zhang L, Kang D, Yang D, Tang Y. Activation of PGE2/EP2 and PGE2/EP4 signaling pathways positively regulate the level of PD-1 in infiltrating CD8(+) T cells in patients with lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:552–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data from the IMvigor210 cohort are freely available under the Creative Commons 3.0 license and can be downloaded from http://research-pub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies. Additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The data from the IMvigor210 cohort are freely available under the Creative Commons 3.0 license and can be downloaded from http://research-pub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies. The schematic and graphic illustration figure was created with BioRender.com.