Abstract

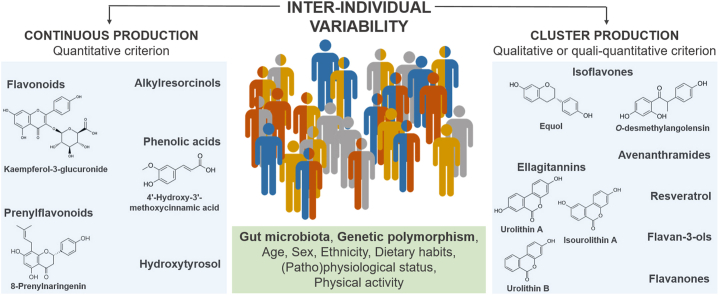

This systematic review provides an overview of the available evidence on the inter-individual variability (IIV) in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of phenolic metabolites and its determinants. Human studies were included investigating the metabolism and bioavailability of (poly)phenols and reporting IIV. One hundred fifty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. Inter-individual differences were mainly related to gut microbiota composition and activity but also to genetic polymorphisms, age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, (patho)physiological status, and physical activity, depending on the (poly)phenol sub-class considered. Most of the IIV has been poorly characterised. Two major types of IIV were observed. One resulted in metabolite gradients that can be further classified into high and low excretors, as seen for all flavonoids, phenolic acids, prenylflavonoids, alkylresorcinols, and hydroxytyrosol. The other type of IIV is based on clusters of individuals defined by qualitative differences (producers vs. non-producers), as for ellagitannins (urolithins), isoflavones (equol and O-DMA), resveratrol (lunularin), and preliminarily for avenanthramides (dihydro-avenanthramides), or by quali-quantitative metabotypes characterized by different proportions of specific metabolites, as for flavan-3-ols, flavanones, and even isoflavones. Future works are needed to shed light on current open issues limiting our understanding of this phenomenon that likely conditions the health effects of dietary (poly)phenols.

Keywords: Bioavailability, Gut microbiota, Inter-person variation, Metabolite, Metabotype, (poly)phenol

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Inter-individual variability (IIV) in the human metabolism and bioavailability of phenolic compounds is often reported.

-

•

The factors underlying IIV are mainly undefined, particularly for some sub-classes of flavonoids and phenolic acids.

-

•

Gut microbiota plays a major role in the inter-individual differences in the ADME of most (poly)phenols.

-

•

Genetic polymorphisms for enzymes associated with (poly)phenol metabolism may play a role in flavanone and flavan-3-ol IIV.

-

•

More comprehensive methodological approaches should be adopted in the future to study IIV in the ADME of (poly)phenols.

1. Introduction

Phenolic compounds or (poly)phenols are plant secondary metabolites commonly found in fruits, vegetables, and beverages like tea, coffee, and wine, widely consumed within the human diet [[1], [2], [3]]. In recent years, epidemiological studies have associated (poly)phenol intake with beneficial health effects on cardiovascular diseases, metabolic diseases, and some types of cancer [[4], [5], [6]]. However, divergent responses have led to controversial results in clinical trials, implying that a “one-size-fits-all” approach is not adequate to explore the potential beneficial effects attributed to dietary phenolic compounds [7,8]. In addition, it is not clear yet whether the health effects attributed to (poly)phenol intake are influenced by the ingested (poly)phenols themselves, which might exert their effects systemically through their derived bioavailable metabolites and catabolites, and/or by a modification of the gut microbial ecology associated with (poly)phenol absorption and metabolism [9]. The existing inter-individual variability (IIV) in (poly)phenol metabolism and response makes solving these key points difficult, blurring the potential that (poly)phenol consumption may have on human health.

Since phenolic metabolites might be mediators of the health effects attributed to dietary (poly)phenols, it is essential to assess the IIV in their production, as well as to understand the main factors affecting this phenomenon. In this sense, the different production of metabolites with different biological activities might condition the response to the consumption of (poly)phenol-rich foods. The molecular mechanisms by which phenolic metabolites may confer their potential health benefits include diverse actions within intra- and inter-cellular signalling pathways, including regulation of nuclear transcription factors and fat metabolism, modulation of the synthesis of inflammatory mediators as cytokines tumour necrosis factor α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, and other direct and indirect antioxidant activities protecting cells and tissues [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. The direct antioxidant effect was the primary mechanism of action attributed to (poly)phenols decades ago by means of in vitro studies, then no longer considered to be as relevant in vivo, due to the low concentrations reached by these compounds in most tissues, not enough to have a significant free radical scavenging effect [10]. However, a recent study has proposed that the reaction rate between phenolic compounds and free radicals is much higher than previously reported, and the antioxidant action does not necessarily require phenolic groups, but only a carbon-centred free radical and an aromatic molecule, restoring an important direct antioxidant role not only for dietary (poly)phenols, but also for their metabolites [12]. In addition, several indirect antioxidant actions have recently been suggested for (poly)phenols and their metabolites. For example, certain dietary (poly)phenols and their metabolites originated in the gut seem to affect aquaporin expression and the intracellular uptake of the oxidant molecule H2O2 mediated by this enzyme, resulting in a H2O2-triggered intracellular down-stream signalling mechanism that protect against excessive generation of reactive oxygen species and the onset of oxidative stress [14]. Also, both native compounds and phenolic metabolites at physiological concentrations might act on NADPH-oxidases, modifying their expression and consequently their capacity to generate oxidant species, potentially mitigating events that are closely associated with inflammation [13].

An effort by researchers involved in the COST Action POSITIVe was made to define IIV in absorption, metabolism, distribution, and excretion (ADME) of (poly)phenols and to assess its impact on cardiovascular health outcomes [8,[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]]. Determinants such as age, sex, genotype, gut microbiota, and (patho)physiological status could lead to differences among subjects in (poly)phenol metabolism and bioavailability, generating a heterogeneous response upon their consumption and highlighting how IIV represents a key aspect that should absolutely be considered [8,20,28]. Nevertheless, the actual contribution and influence of each factor in determining IIV is still unknown for most of the (poly)phenol classes.

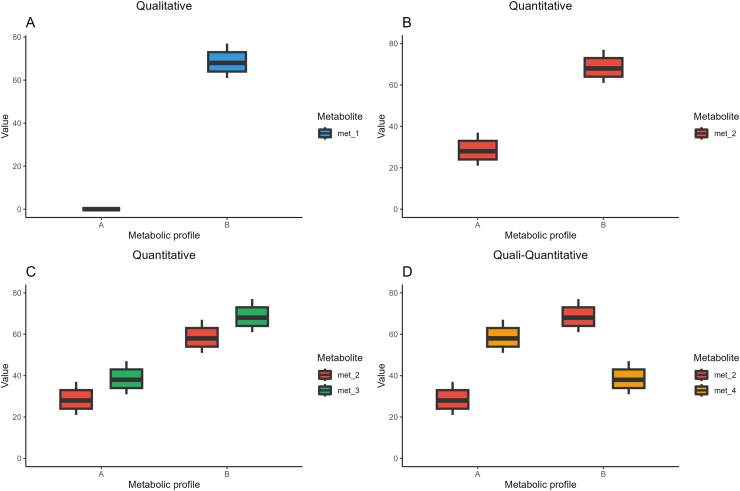

Among the factors driving IIV, the gut microbiota, which plays a crucial role in (poly)phenol metabolism, is believed to underpin much of the IIV observed [29]. Well-established examples of microbiota-dependent variation are the formation of urolithins, from ellagic acid and ellagitannins, and that of equol and O-desmethylangolensin (O-DMA) from the isoflavone daidzein. In these cases, metabolic phenotypes (aka “metabotypes”) have been described and characterized by the selective production or non-production of these catabolites, due to a specific gut microbiota ecology [30,31], and some authors refer to these clusters as “gut metabotypes” or “gut microbiota-associated metabotypes” [9]. For other (poly)phenol classes, an attempt to unravel metabotypes has been made, based on quantitative (catabolite production gradient) or quali-quantitative (different production proportions among specific catabolite classes) criteria, even if the causes responsible for the observed differences were not firmly identified [32]. Not only differences in the production of microbial metabolites, but also the ratio between phase II sulfates and glucuronides or the proportion of methylated derivatives have been proposed as putative indicators of inter-person variation in the metabolism of (poly)phenols, attributable to variable enzymatic activities and perhaps also to genotypic diversity [[33], [34], [35]]. Therefore, we consider that phenolic metabotypes can be reported when the variability is well characterized from a metabolomics/statistical point of view, even when the causes behind their formation are unknown. This concept is fully in line with the broad definition for “metabotype” commonly adopted in the nutrition [36] and medical [37] fields, where metabotypes are defined as subgroups of individuals sharing similar combinations of specific metabolites or metabolic profiles. These metabolic profiles can be qualitative (production vs. non-production of specific metabolites), quantitative (high- vs. low-production of metabolites), or quali-quantitative (different production proportions of specific metabolites) (Fig. 1). Although the term “metabotype” can be applied in sensu lato to these three cases, it is better to use it just for qualitative and quali-quantitative metabolic profiles as the metabolic capacities are clearly different, while in the case of quantitative profiles the term high/low producers/excretors is preferred. Of note, if robustly managed from a metabolomics and statistics point of view, all these ways of classifying individuals may help understand the factors driving the inter-individual variability in the metabolism and bioavailability of phenolic compounds.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the possible existing metabolic profiles. A) Metabotypes based on a qualitative criterion are characterized by the production vs. non-production of specific metabolites. B–C) Quantitative metabolic profiles are characterized by high- vs. low-production of one (B) or more (C) metabolites; in this case the term “high/low producers”, instead of “metabotypes”, is preferred (other terms like “excretors” or “producer phenotypes” could also be used instead of the term “producers”). D) Quali-quantitative metabolic profiles are characterized by different proportions of specific metabolites belonging to the same metabolic pathway, and thus reflecting different metabolic capacities. A and B in the x-axis legend identify two distinct metabolic profiles, while “value” in the y-axis legend can be a concentration or excretion measure.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic approaches gathering data on several (poly)phenol classes are available on the IIV in (poly)phenol metabolism and its main determinants. Therefore, this systematic review aims to provide an overview of the available scientific evidence on inter-individual differences in phenolic metabolite and catabolite production and bioavailability. In order to define the factors affecting individual differences, only papers that reported IIV were considered. Furthermore, suggestions for taking IIV into account in future studies assessing the health-related consequences of (poly)phenol intake were provided.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

This systematic review was developed in line with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement guidelines [38,39]. The systematic literature search was conducted in July 2022 using Scopus (https://www.scopus.com) and the Web of Science (http://apps.webofknowledge.com) databases, using the syntaxes reported in Supplemental Table 1. The literature search was updated in June 2023. No temporal or spatial filters were applied to the search. Reference lists of included manuscripts were also examined for any additional studies not previously identified. Studies were included in the present systematic review if they (i) were human studies supplying to subjects sources of (poly)phenols (either a food, an extract or a pure compound), (ii) investigated the ADME/bioavailability of (poly)phenols, and (iii) reported IIV in (poly)phenol ADME/bioavailability. Exclusion criteria included studies published in a non-European language. No restrictions for the characteristics of study participants (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity and health condition) were applied.

2.2. Data extraction

The systematic literature search was independently conducted by 2 authors (CF and JRA), who independently assessed the studies for their inclusion. Discrepancies between authors were resolved through consultation with a third independent reviewer (PM). Data from each study were extracted using a standardized form, and the following information was collected: name of the first author; year of publication; description of the study population; (poly)phenol source; (poly)phenol class or specific compound(s) administered; specific metabolite(s) produced for which IIV was reported; type of biofluid(s) in which metabolites were detected and/or quantified; the outcome of ADME/bioavailability (e.g. AUC, urinary excretion, plasma concentration …); type of IIV (continuous production or cluster production); clustering method and data normalization strategy, if reported; explanation of IIV; and potential IIV source. To clarify, continuous production indicates that all the subjects are able to produce a metabolite but in different amounts, so that, in certain cases, it is possible to classify subjects as high- vs. low-producers/excretors. Cluster production instead describes a production of metabolite(s) characterized by qualitative (when subjects are producers vs. non-producers of a specific metabolite or pool of metabolites) or quali-quantitative differences (when subjects produce different proportions of the same pool of metabolites). A detailed description of the collected paper characteristics has been listed in the supplemental material. When studies reported several pharmacokinetic parameters (i.e., Tmax, Cmax, AUC, and t1/2) as bioavailability outcomes, only the AUC value was taken into consideration to calculate the percentage of the coefficient of variation (CV%), as this datum was considered more representative of the bioavailability of a metabolite.

2.3. Data analysis

Chemical names of circulating metabolites and catabolites were standardized according to Kay et al. [40]. Several strategies were adopted to report IIV as described in the selected studies, in accordance with the type of data presented, type of IIV observed, and statistical analysis performed. Only statistically significant results were considered based on the reported p values or VIP values. When the type of IIV observed was continuous, i.e. all subjects produced the same metabolite(s) or catabolite(s) but in different amounts, as expressed by a high standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM) presented together with the mean value or by a high CV%, this latter index was considered as representative of IIV [41]. If not reported, CV% was calculated using the SD or SEM using the formula CV% = 100 × SD/mean or CV% = 100 X (SEM × √n)/mean, where is the number of volunteers. CV% higher than 50% were considered relevant descriptors of IIV, according to Almeida et al. [15]. In a few cases, CV% was impossible to calculate, and fold-variation between low and high producers was reported. When IIV was characterized by producers and non-producers of specific metabolite(s) or catabolite(s), the number of producers and non-producers was reported as a percentage with respect to the study population.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Study selection

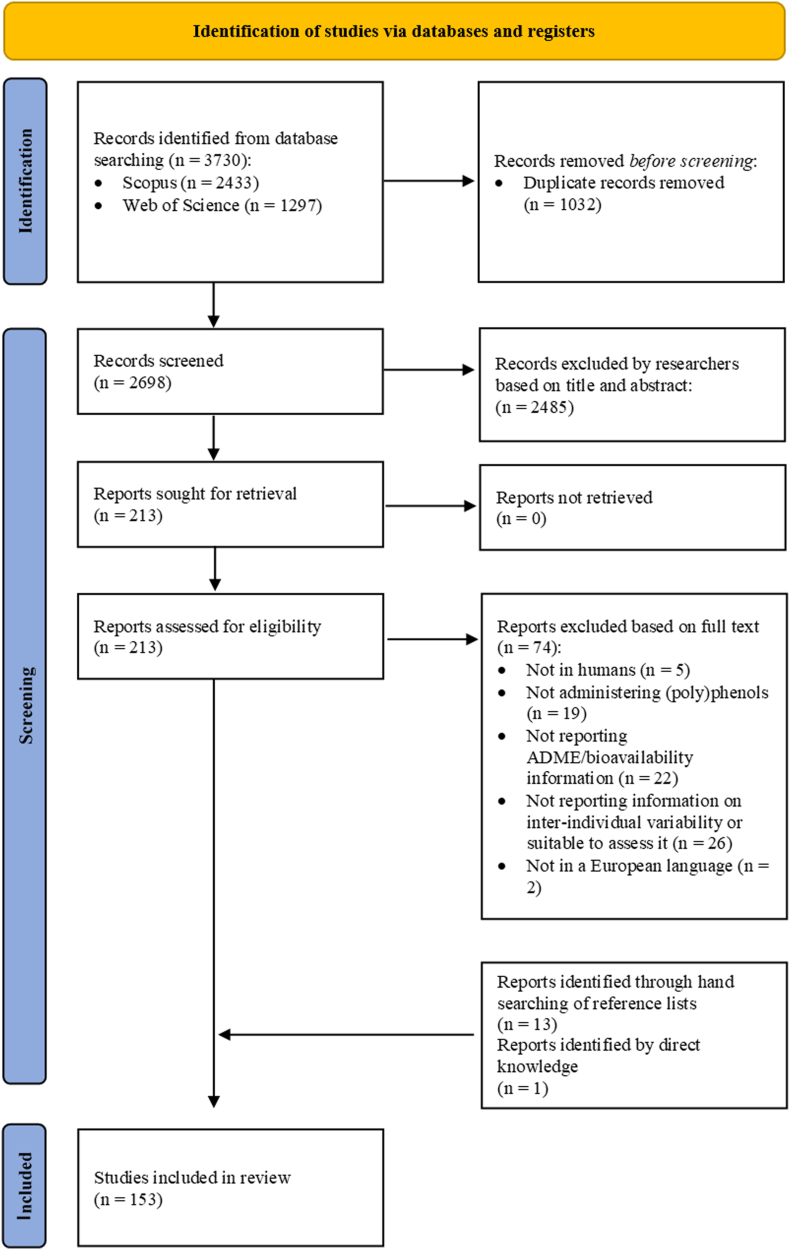

The study selection process is shown in Fig. 2. A total of 3730 records were collected through database searches. After removing 1032 duplicates, up to 2698 studies were screened, of which 2485 were excluded based on title or abstract. A total of 213 eligible records underwent the full-text screening, after which 74 records were excluded. Thirteen studies were identified through manual search in reference lists. Finally, 153 publications met the eligibility criteria and were included in the data analysis.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of the included studies

The main characteristics of the studies that met all inclusion criteria are reported in Table 1 and Supplemental Tables 2–8.

Table 1.

Selection of studies reporting inter-individual variability for different classes of phenolic metabolites.

| Reference | Population | (Poly)phenol source | (Poly)phenol class/specific compound(s) | Specific metabolite(s) | Biofluid | Outcome of ADME/bioavailability | IIV type | Clustering method | IIV explanation | IIV source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavan-3-ols | ||||||||||

| Mena et al., 2022 [75] |

(a) n = 10 (0F/10 M); Age: 18.0– – 35.0 y/o; Healthy (b) n = 22 (0F/22 M); Age: 18.0– – 45.0 y/o; Healthy |

(a) Cranberry drinks containing 716, 1131, 1396 and 1741 mg total flavan-3-ols (b) Cranberry powder containing 0.5 mg of flavan-3-ol monomers and 374 mg of proanthocyanidins |

Flavan-3-ols |

1. 3ʹ-HPVLs 5-Phenyl-γ-valerolactone-3ʹ-sulfate 5-Phenyl-γ-valerolactone-3ʹ-glucuronide 2. 4ʹ-HPVLs 5-Phenyl-γ-valerolactone-4ʹ-glucuronide 3. 3ʹ, 4ʹ-dHPVLs 5-(3ʹ,4ʹ-Dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone 5-(Hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone-sulfate (3ʹ,4ʹ isomers) 5-(4ʹ-Hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone-3ʹ-glucuronide 5-(3ʹ-Hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone-4ʹ-glucuronide 5-Phenyl-γ-valerolactone-methoxy-sulfate isomer 5-Phenyl-γ-valerolactone-sulfate-glucuronide isomer 4. 3-HPPAs 3-(Phenyl)propanoic acid-sulfate 3-(Phenyl)propanoic acid-glucuronide |

U |

24-h cumulative excretion (μμmol) |

ClP |

Final Consensus K-means Expectation-maximization PCA-based, forming 2 clusters PCA-based, forming 3 clusters Normalization: centering + unit variance scaling Ratio of sulfate/glucuronide derivatives |

↑ vs ↓ PVLs producers ↑ vs ↓ PVLs producers ↑ vs ↓ 4ʹ-HPVLs and 3-HPPAs producers Cluster 1: ↑ 4ʹ-HPVLs, ↑ 3-HPPAs and ↓ 3ʹ, 4ʹ-dHPVLs producers Cluster 2: ↑ 3ʹ, 4ʹ-dHPVLs and ↓ 4ʹ-HPVLs, ↓ 3-HPPAs producers Cluster 1: ↑ 3ʹ-HPVLs, ↑ 4ʹ-HPVLs, ↑ 3-HPPAs and ↓ 3ʹ, 4ʹ-dHPVLs producers Cluster 2: ↑ 3ʹ, 4ʹ-dHPVLs and ↓ 3ʹ-HPVLs, ↓ 4ʹ-HPVLs, ↓ 3-HPPAs producers Cluster 3: ↓↓ PVLs producers ↑ excretors of sulfate derivatives vs ↑ excretors of glucuronide derivatives |

Undefined |

| Mena et al., 2019 [74] | n = 11 (9F/2 M); Age: 18.0– -45.0 y/o; BMI: 18.5– - 24.9 kg/m2; Healthy | Tablets of green tea exctract | Flavan-3-ols | 1. TrihydroxyPVLs 2. DihydroxyPVLs 3. 3-(3′-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acids (as sum of all the derivatives belonging to the same aglycone moiety) 4. (+)-Catechin 5. (Epi)catechin-glucuronide 6. (Epi)catechin-sulfate 7. Methoxy-(epi)catechin-glucuronide 8. Methoxy-(epi)gallocatechin-sulfate-glucuronide 9. Methoxy-(epi)gallocatechin-glucuronide 10. 5-(Phenyl)-γ-valerolactone-3′-glucuronide 11. 5-(Phenyl)-γ-valerolactone-3′-sulfate 12. 5-(4′-Hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone |

U | Excretion (μμmol/24h) | ClP CoP |

PLS-DA + one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett'’s T3 test n.a. | Metabotype 1 (36.3%): ↑ triydroxyPVLs, ↑ dihydroxyPVLs, ↓ 3-(hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid Metabotype 2 (45.5%): medium dihydroxyPVLs, ↓ trihydroxyPVLs, ↓ 3-(hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid Metabotype 3 (18.2%): ↓ trihydroxyPVLs, ↓ dihydroxyPVLs, ↑ 3-(hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid 4. CV (%) = 60 5. CV (%) = 51 6. CV (%) = 53 7. CV (%) = 83 8. CV (%) = 55 9. CV (%) = 133 10. CV (%) = 115 11. CV (%) = 121 12. CV (%) = 122 |

Undefined |

| Flavanones | ||||||||||

| Fraga et al., 2022 [90] |

n = 46 (26F/20 M); Age: 19–-38 y/o; BMI: 23.23 ± 2.54 kg/m2;Healthy |

Pasteurized orange juice (500 mL-Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck var. Pera) |

Flavanones |

1. Phase II flavanone metabolites (total) |

U |

Excretion (ng equivalents/24h) |

CoP |

Defined thresholds |

↑ vs ↓ excretors ↑ excretors are associatedassocitaed with GGCC and GCTG haplotypes for ABCC2_rs8187710/SULT1A1_rs3760091/SULT1A1_rs4788068/SULT1C4_rs1402467 |

Genetic polymorphisms |

| Fraga et al., 2021 [91] | n = 74 (F/M); Age: 19.0– - 40.0 y/o; Eutrophic (n = 53); Age: 26.5 y/o; BMI: 22.0 kg/m2;HealthyOverweigh (n = 21); Age: 26.5 y/o; BMI: 27.0 kg/m2;Healthy | Pasteurized orange juice (500 mL-Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck var. Pera) | Flavanones | Flavanone phase II conjugates 1. Hesperetin-7-glucuronide 2. Hesperetin-3′-glucuronide 3. Hesperetin-glucuronyl-sulfate 4. Hesperetin -diglucuronide 5. Hesperetin-sulfate 6. Naringenin-7-glucuronide 7. Naringenin-isomer 8. Naringenin-glucuronyl-sulfate 9. Hippuric acid 10. 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid 11. 3′-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid 12. 4′-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid 13. 3-(4′-Hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid |

U | Total excretion (mg/24 h) | CoP | oPLS-DA ContinuousRatio (phenolic acids /flavanone phase II conjugates) |

34% ↑ excretors 38% medium excretors 21% ↓ excretors Low ratio: flavanone phase II conjugates (↑) vs phenolic acid (↓) Intermediate ratio: flavanone phase II conjugates (=) vs phenolic acid (=) High ratio: flavanone phase II conjugates (↓) vs phenolic acid (↑) |

Undefined |

| Isoflavones | ||||||||||

| Soukup et al., 2023 [92] |

n = 59 (59F/0 M); Healthy, being post menopause |

Isoflavone-enriched soy extract |

Isoflavones |

1. Daidzein 2. Genistein 3. Dihydrodaidzein 4. Dihydrogenistein 5. O-DMA, 6. 6-OH-O-DMA 7. Equol 8. 4-Ethylphenol |

U |

Excretion (μμmol) |

ClP |

HCA with Ward method Normalization by the total amount of isoflavone equivalents excreted (%) |

Metabotype 1 (12%): equol producer, ↑ Genistein, ↓ 4-Ethylphenol Metabotype 2 (17%): equol producer, ↓ Genistein, ↑ 4-Ethylphenol Metabotype 3 (25%): ↑↑ 4-Ethylphenol Metabotype 4 (39%): ↑↑ Daidzein, ↑↑ Genistein Metabotype 5 (7%): ↑↑ Dihydrodaidzein, ↑↑ Dihydrogenistein |

Gut microbiota |

| de Oliveira Silva et al., 2020 [93] | n = 18 (10F/8 M); Age: 19.0– -32.0 y/o; BMI: 23.2 ± 2.4 kg/m2; Healthy | Soybean meal (SBM) and fermented soybean meal (FSBM) biscuits | Isoflavones | 1. Total aglycones (glycitein, genistein, daidzein) 2. Total colonic metabolites (dihydrodaidzein, dihydrogenistein, O-DMA, 6-OH-O-DMA, equol) 3.O-DMA 4. Equol |

U | Excretion (μμmol) | CoP CoP ClP |

n.a n.a. Presence vs absence of specific metabolites |

1. 29% ↑ in M 2. 51% ↑ in F 64% O-DMA-producers, 25% non-producers, 11% equol-producers |

Sex Sex Gut microbiota |

| Ellagitannins | ||||||||||

| Cortés-Martín et al., 2018 [94] |

n = 839 (442F/397 M); Age: 5.0– – 90.0 y/o; Normoweight, overweight, obese; Healthy and with colorectal cancer, metabolic syndrome, prostate cancer |

Walnuts (peeled), pomegranate juice or pomegranate extract |

Ellagitannins |

1. Urolithin A and conjugates 2. Urolithin B and conjugates 3. Isourolithin A and conjugates |

U |

Excretion (n.a.) |

ClP |

Presence vs absence of specific metabolites |

Metabotype 0 constant in the age range (mean 10.4 ± 1.9%) Metabotype A ↓ with ↑ age (from 80.8 ± 9.3% to 52.1 ± 5.3%) Metabotype B ↑ with ↑ age (from 8.2 ± 8.5% to 40.7 ± 4.6%) Metabotype A ↓ with ↑ BMI in the age range 5– – 40 y/o Metabotype B ↑ with ↑ BMI in the age range 5– – 40 y/o |

Gut microbiota Age BMI (nutritional status) |

| Selma et al., 2018 [95] | n = 94 (36F/58 M); (a) Healthy, normoweight: n = 20 (9F/11 M); BMI: <25.0 kg/m2; (b) Healthy, overweight-obese: n = 49 (17F/32 M); BMI: >27.0 kg/m2; (c) With MetS: n = 25 (10F/15 M) |

Nuts (peeled) or pomegranate extract | Ellagitannins | 1. Urolithin A and conjugates 2. Urolithin B and conjugates 3. Isourolithin A and conjugates |

U | Excretion (n.a.) | ClP | Presence vs absence of specific metabolites | Metabotype B ↑ in MetS (41%) than overweight-obese (31%) than normoweight (20%) Metabotype A ↑ in normoweight (70%) than overweight-obese (57%) than MetS (50%) Metabotype 0 constant around 10% |

Gut microbiota Nutritional status (Patho)physiological state |

| Lignans | ||||||||||

| Mullens et al., 2022 [96] |

n = 42 (22F/20 M); Age: (F): 31.4 ± 8.0 (M): 33.2 ± 8.7 y/o; BMI: (F): 27.7 ± 7.4 (M): 26.0 ± 3.9 kg/m2; Healthy |

Flaseed lignan extract |

Lignans |

1. Enterolactone 2. Secoisolariciresinol 3. Enterodiol |

U |

Excretion 0–-24h (μμmol/24h) |

CoP |

Defined threshold n.a. n.a. |

1. ↓vs ↑ producers 2. ↑ for ↑ ENL producers 3. ↑ for ↑ ENL producers |

Gut microbiota Undefined |

| Navarro et al., 2020 [97] | n = 46 (23F/23 M); Age: 32.1 ± 8.4 y/o; BMI: 26.7 ± 5.8 kg/m2; (a) ↓ENL = 23 (11F/12 M); Age: 33.1 ± 9.3; BMI: 27.2 ± 7.1 kg/m2; (b) ↑ENL = 23 (12F/11 M); Age: 31.1 ± 7.6 y/o; BMI: 26.2 ± 4.3 kg/m2 |

Flexseed lignan extract | Lignans | 1. Enterolactone 2. Secoisolariciresinol 3. Enterodiol |

U | Excretion 0–-24h (μμmol/24h) | CoP | Defined threshold n.a. n.a. |

1. ↓vs ↑ producers 2. CV (%) = 120 (↓ENL), 133 (↑ENL) 3. CV (%) = 250 (↓ENL), 218 (↑ENL) |

Gut microbiota Undefined |

| Stilbenes | ||||||||||

| Iglesias-Aguirre et al., 2022 [98] |

n = 195 (124F/71 M); Age: 18.0– - 81.0 y/o; BMI: 25.7 ± 5.0 kg/m2; Healthy |

Hard gelatine capsule |

Resveratrol |

1. Lunularin and conjugates 2. 4-Hydroxydibenzyl 3. 3,4ʹ-Dihydroxy-trans-stilbene |

U |

Excretion (n.a.) |

ClP |

Presence vs absence of specific metabolites Sex Presence vs absence of specific metabolites |

74.4% producers, 25.6% non-producers ↑ vs medium vs ↓ lunularin producers 30.6% F vs 16.9% M lunularin producers Present only in lunularin producers |

Gut microbiota Sex |

| Bode et al., 2013 [99] | n = 12 (F/M); Age: 19.0– - 28.0 y/o; BMI: 20.0– - 26.0 kg/m2; Healthy | Colloid formulation (0.5 mg transtrans-resveratrol/kg body weight) | trans-resveratrol | 1. Dihydroresveratrol 2. 3,4′'-dihydroxy-trans-stilbene 3. 3,4′'-dihydroxybibenzyl (lunularin) |

U | Urinary excretion (% of the oral dose of trans-resveratrol) | ClP | n.a. | Cluster 1: 3,4′'-dihydroxybibenzyl production Cluster 2: Dihydroresveratrol production Cluster 3: Mixed production of dihydroresveratrol and 3,4′'-dihydroxybibenzyl |

Gut microbiota |

| Prenylflavonoids | ||||||||||

| Bolca et al., 2009 [53] | n = 50 (50F/0 M); Age: 44.0– - 76.0; BMI: 24.4 ± 4.0 g/m2; Healthy, being post menopause |

Hop extract | Prenylflavonoids | 1. 8-prenylnaringenin 2. Isoxanthohumol |

U | Excretion [ratio 8-prenylnaringenin /8-prenylnaringenin + Isoxanthohumol)] | CoP | TwoStep cluster analysis protocol Normalization: calculated ratios 8-prenylnaringenin /(8-prenylnaringenin + Isoxanthohumol) |

14% Strong producers 24% Moderate producers 62% Poor producers |

Gut microbiota |

| (Poly)phenols | ||||||||||

| Tosi et al., 2023 [50] |

n = 60 (F/M); Age: 50– – 80 y/o; Healthy |

Free-living diet with cranberry powder supplementation in the treated group |

(Poly)phenols |

1. 3ʹ-HPVLs 2. 3ʹ,4ʹ-dHPVLs 3. 3ʹ-HCAs 4. 3-HPPAs 5. 3-HBAs |

U |

Excretion (μμmol/mmol creatinine) |

ClP |

PCA- and PLS-DA-based, forming 3 clusters Normalization: centering + unit variance scaling |

Metabotype 1: ↑ 3ʹ-HPVLs and ↑ 3ʹ, 4ʹ-dHPVLs producers Metabotype 2: ↑ 3ʹ-HCAs, ↑ 3-HPPAs, ↑ 3-HBAs producers Metabotype 3: ↓↓ metabolite producers |

Undefined |

| Muñoz-González et al., 2013 [100]; Belda et al., 2021 [101] |

n = 33 (F/M); Age: 20.0– – 65.0 y/o | Red wine | Benzoic acids Phenols Phenylacetic acids Phenylpropionic acids Cinnamic acids Silbenes Flavan-3-ols Flavonols Anthocyanins |

Total polyphenols metabolites | Fe | Excretion (μμg/g) | CoP | Tertiles of low (<500), medium 500–-1000), and high (>1000) polyphenol excretion | 21% ↑ excretors 39% medium excretors 39% ↓ excretors |

Undefined Gut microbiota |

ADME, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion; IIV, inter-individual variability; F, females; M, males.

3ʹ-HPVLs, 3ʹ-(hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactones; 4ʹ-HPVLs, 4ʹ-(hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactones; 3ʹ,4ʹ-dHPVLs, 3ʹ,4ʹ-(dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactones; 3ʹ-HCAs, 3ʹ-hydroxycinnamic acids; 3-HPPAs, 3-(3′-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acids; 3-HBAs, 3-hydroxybenzoic acids; ENL, enterolactone.

U, urine; Fe, feces; ClP, cluster production; CoP, continuous production; CV%, coefficient of variation (in percentage); n.a., not available.

PCA, principal component analysis; PLS-DA, partial least squares-discriminant analysis; oPLS-DA, orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis; HCA, hierarchical clustering analysis; BMI, body mass index; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

Of the 153 intervention studies reporting IIV in the metabolism and absorption of phenolic metabolite(s) and catabolite(s), 24 papers dealt with more than one (poly)phenol sub-class [33,[54], [55], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78]]. Isoflavones and ellagitannins were the most investigated (poly)phenol sub-classes, covering about 26% and 21% of selected papers, respectively. Phenolic acids accounted for 19% of extracted studies, whereas flavan-3-ols covered 16%. The remaining ADME/bioavailability papers included pharmacokinetics or urinary data on flavonols (7%), flavones (3%), flavanones (11%), anthocyanins (4%), lignans (7%), stilbenes (4%), other minor phenolic sub-classes like flavononols, prenylflavonoids, alkylresorcinols, tyrosols and oleuropeins, avenathramides, phlorotannins and benzene triols (7%) and (poly)phenols in general (2%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The number of selected studies reporting IIV in the bioavailability of the different phenolic sub-classes. Each square represents one study and different colours indicate different phenolic sub-classes, so the higher the number of squares having the same colour, the higher the studies available for that sub-class. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Most papers were intervention studies with (poly)phenol-rich extracts or foods. Only a few studies presenting observational data were included [[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87]].

3.3. Inter-individual variability in the metabolism and bioavailability of phenolic metabolites and driving factors

3.3.1. Flavonoids

3.3.1.1. Flavan-3-ols

Flavan-3-ol metabolites for which IIV has been reported are both native ones, as proanthocyanidins and (epi)(gallo)catechins, and gut microbiota-derived catabolites, such as tri/di/mono-hydroxyphenyl-γ-valerolactones (PVLs) and phenylvaleric acids (PVAs), either described as aglycones or as conjugates (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2). 3-(Hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acids (3-HPPAs) and their conjugates, important catabolites of flavan-3-ols, as well as common metabolic end-products of several (poly)phenol sub-classes have been discussed in the Phenolic acids section (3.3.2.1.) and presented in Supplemental Table 6, except for four studies in which these metabolites were inextricably considered for the definition of flavan-3-ol metabotypes and are thus presented here, in Tables 1 and in Supplemental Table 2 [33,43,42].

In general, high and low producers of flavan-3-ol metabolites have been observed (continuous production), as reported by authors or highlighted by high CV% and fold-variations [34,60,63,66,70,72,74,78,[88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93]]. However, high producers of native compounds are not necessarily high or low producers of gut microbiota-derived catabolites, as the inter-relationship between these two metabolite classes has rarely been assessed [89].

Regarding native metabolites, most studies simply showed IIV in their plasma concentrations or urinary excretion without determining specific factors responsible for the observed IIV. Actis-Goretta et al. [90] found large IIV in the absorption of (−)-epicatechin after perfusion of purified (−)-epicatechin into an isolated jejunal segment of 6 volunteers, as determined by inter-subject different recovery of (−)-epicatechin in intestinal perfusates. Similarly, the amount of (−)-epicatechin phase II metabolites detected in bile and urine varied considerably among individuals, with one subject excreting higher amounts of (−)-epicatechin metabolites in bile than the rest of the volunteers and, consequently, presenting lower amounts of these metabolites in urine. Despite the small number of volunteers prevented from reaching any firm conclusion, authors assumed that different rates of metabolism could be one of the most important variables determining the overall absorption of (−)-epicatechin [90].

In another study, age was hypothesized as a potential cause for IIV in the ADME of native flavan-3-ol metabolites [94]. Authors only found slight differences between young and elderly when the highest dose of cocoa flavan-3-ols foreseen in the study was administered, while no significant difference was observed between age groups when the lowest cocoa flavan-3-ol dose was consumed. In detail, differences were observed in plasma levels of sulfated and glucuronidated (epi)catechin metabolites and were explained by differences in the elimination rate, suggesting that the expected decline of renal function with age may influence the plasma levels of phase II (epi)catechin metabolites in elderly [94].

When a green tea extract was administered to 84 healthy participants [93], IIV in the pharmacokinetics of (−)-epigallocatechin, (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate, and (−)-epicatechin-gallate was not associated with sex, age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), lifestyle parameters (such as smoking, alcohol consumption or habitual consumption of green tea), nor with polymorphisms in the genes coding p-glycoprotein (Pgp) and sulfotransferase 1A1 (SULT1A1). However, inter-person differences were associated with the use of contraceptives and inherent genetic variations in genes coding for multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) and organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) for (−)-epigallocatechin and (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate [93].

Andreu Fernández et al. [95] reported greater IIV differences in AUC values for epigallocatechin-gallate in males than females, suggesting a potential influence of sex. Unfortunately, further studies that corroborate all these findings are missing.

Concerning gut microbiota catabolites, attempts to define flavan-3-ol metabotypes based on the differential quali-quantitative urinary excretion of PVLs and 3-HPPAs (cluster production) have been performed in recent years. Firstly, three putative metabotypes were proposed after consumption of an (epi)gallocatechin-rich green tea extract: metabotype 1 was characterized by high excretion of tri- and dihydroxyPVLs and reduced excretion of 3-HPPAs; metabotype 2 was distinguished by a medium excretion of dihydroxyPVLs and a limited excretion of trihydroxyPVLs and 3-HPPAs; and metabotype 3 was characterized by a limited production of PVLs and high amounts of 3-HPPAs [43]. Later works reported similar findings, although flavan-3-ol precursors differed from those of green tea and did not include trihydroxylated compounds, namely (epi)gallocatechin derivatives [33,55,42]. The resulting picture was more straightforward but consistent, as authors reported at least two urinary flavan-3-ol metabotypes after consumption of cranberry and nuts: one cluster characterized by a high excretion of 3-HPPAs and monohydroxyPVLs, and a reduced excretion of dihydroxyPVLs, whereas the other cluster by a high excretion of dihydroxyPVLs and low excretions of smaller catabolites (monohydroxyPVLs and 3-HPPAs) [33,42]. At the same time, depending on the clustering technique used, a third cluster, characterised by a low excretion of all the metabolites, was also observed [33,55,42]. Indeed, a particular influence of the normalization method, as well as the clustering algorithm used (i.e., distance- or density-based), has emerged when defining metabotypes originating from quali-quantitative differences in metabolite production [42].

Despite a certain robustness of the evidence for colonic metabotypes of flavan-3-ols, further ad hoc confirmatory research is required to consolidate this observation and fully understand the factors behind these differences, as well as their possible health-related consequences. Among the factors to be considered, gut microbiota composition and bioconversion capacity are likely the main variables determining the observed IIV, but efforts are needed to identify the microbial species responsible for the different catabolism of flavan-3-ols. Information on specific bacterial strains responsible for the bioconversion of flavan-3-ols into PVLs and low molecular weight phenolics is currently scarce. Van Velzen et al. [66] positively correlated dihydroxyPVL production with members of Clostridia and Actinobacteria, including Clostridium leptum, Flavonifractor plautii, Ruminococcus bromii, Sporobacter termitidis, and Eubacterium ramulus, and the genus Propionibacterium. Lactobacillus plantarum IFPL935, Eggerthella lenta, Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, and Flavonifractor plautii are the only bacteria identified being able to convert flavan-3-ols into 5-(3′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone and 5-(3′-hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone, but no microorganisms responsible for further catabolism into PVAs and 3-HPPAs have yet been identified [96,97]. On the other hand, transit time should also be considered as it may drive the metabotypes elucidated so far.

Lastly, a certain IIV in phase II metabolism of gut-microbiota catabolites has been reported, mainly related to dihydroxyPVLs, with subjects excreting higher amounts of glucuronide than sulfate derivatives, or vice versa [33,35,42]. This fact has also been observed for (epi)catechin derivatives [35]. This variability could be related to genetic polymorphisms in phase II enzymes [[98], [99], [100]], but also to the dose of flavan-3-ols consumed. It has been reported that the sulfonation pathway has higher affinity but lower efficiency than the glucuronidation one, and when the ingested amount of flavan-3-ols increases, a shift from sulfation toward glucuronidation might occur [101]. Future studies will elucidate this and further document the stability of the phenotype over time and ingested doses, to finally evaluate its potential relevance for human health.

3.3.1.2. Flavonols

Data on IIV in the ADME of flavonol metabolites have been mainly reported for kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin, either as aglycones or phase II conjugates, and for two methylated derivatives of quercetin, namely isorhamnetin and tamarixetin (Supplemental Table 3). Unspecific phenolic acids that can originate from gut microbiota catabolism of flavonols in the large intestine have been reported in Supplemental Table 6.

For flavonol native metabolites, IIV in their plasma concentration and urinary excretion has been observed, as expressed by the high CV% (continuous production), but no specific factor has been associated to the observed inter-individual differences (Supplemental Table 3) [59,63,74,78,[102], [103], [104], [105]]. One study performed on just 7 healthy volunteers reported a correlation between the percentage of kaempferol excreted upon bean consumption and the BMI of volunteers, with higher kaempferol excretion observed for lower BMI [106]. Sex and gut microbiota were also investigated as potentially responsible for the IIV observed in quercetin AUC values after consumption of quercetin and rutin (quercetin-rutinoside) by 16 healthy subjects [107]. While a small level of IIV was observed after quercetin aglycone intake, rutin consumption by females led to higher quercetin AUC and Cmax values, with subjects using oral contraceptives having the highest values. It was hypothesized that women's microbiota was able to hydrolyze sugar moieties more efficiently than men's, and this might be linked to the use of oral contraceptives [107].

Despite these interesting results, 8 out of 10 studies included herein did not specify any possible cause of the observed IIV [59,63,74,78,[102], [103], [104], [105]]. Accordingly, Almeida et al. [15] recently reviewed the IIV in quercetin bioavailability in humans and did not manage to establish the causes behind the reported IIV, although suggesting a potential implication of genetic polymorphisms, dietary adaptation, composition of gut microbiota, drug exposure, and other subject characteristics such as BMI and health status. These factors may be common to many other phenolic families.

3.3.1.3. Flavones

Scarce IIV data were found for flavones, mainly related to luteolin and apigenin phase II metabolites, which are characterized by high CV% in urinary excretion (Supplemental Table 3) [63,65,108]. Phenolic acid catabolites that can originate from gut microbiota catabolism of flavones have been reported in Supplemental Table 6.

A recent study by Tomás-Navarro et al. [65] reported different levels of urinary excretion of phase II derivatives of hydroxy-polymethoxyflavones, demethylated metabolites of specific flavones found in orange juice. Upon definition of excretion levels as high (if above 10% of the intake), medium (between 5 and 10% of the intake), and low (if below 5% of the intake), the possible existence of three quantitative groups of high, medium and low excretors of these polymethoxyflavone metabolites was suggested (continuous production) [65]. In addition, in the study, three quantitative groups of high, medium and low excretors of phase II metabolites of flavanones (flavonoids also present in orange juice) were reported (see the paragraph “Flavanones” below). However, no correlations between the suggested quantitative phenotypes for polymethoxyflavone metabolites and those observed in the excretion of flavanone phase II metabolites were observed. The potential factors responsible for the presence of the quantitative phenotypes for polymethoxyflavone metabolites observed could not be elucidate, but the involvement of gut microbiota and CYP1A1 polymorphisms in the demethylation of polymethoxyflavones was hypothesized [65].

3.3.1.4. Flavanones

Regarding flavanones, IIV has been observed for unchanged compounds and phase II metabolites (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 4) and gut microbiota-derived phenolic acids described in the Phenolic acid section and in Supplemental Table 6. For unchanged and phase II metabolites, most of the studies reported a continuous production [65,44,[109], [110], [111]], sometimes reporting the existence of two/three groups, depending on the amount of flavanone metabolites excreted and thresholds considered, thus classifying subjects into high, medium and low/no producers [65,45,109,110,112] or high and low/no producers [44,111,113].

In some instances, polymorphisms in phase II enzymes and transporters have been associated with the observed quantitative metabotypes. For example, Fraga et al. [44] associated high excretion of phase II flavanone metabolites with GGCC and GCTG haplotypes for the ABCC2_rs8187710, SULT1A1_rs3760091, SULT1A1_rs4788068, and SULT1C4_rs1402467 enzymes involved in the efflux of flavanone metabolites back to the intestinal lumen (which may limit the bioavailability of these compounds) and their conjugation with a sulfate moiety (which favours their elimination in urine). In some other cases, the influence of polymorphisms in phase I enzymes (in particular CYP1A1 and CYP2A6) has been suggested as a potential explanation of the observed IIV, although no confirmatory results have been found [65,109].

Nishioka et al. [110] observed two different flavanone metabotypes, one characterized by a lower excretion, a slower excretion rate and a lower glucuronidation rate (profile A), and the other one conversely showing higher excretion, a faster excretion rate, and a higher glucuronidation rate (profile B). These differences were attributed to a possible involvement of polymorphic variants of the phase II enzyme UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT). These metabolic profiles (A and B) did not correlate with quantitative metabotypes defined in the same studies for total flavanone metabolites excretion (high, medium and low excretors of total flavanone metabolites). Moreover, subjects classified as profile B showed a greater abundance of species responsible for the O-deglycosylation of flavanones (Bacteroides uniformis and Bifidobacterium bifidum), while a Clostridium sp., related to the C-ring fission, was exclusively found in profile A individuals. However, the meaning of these observations still need to be clarified [110].

The urinary excretion of phase II flavanones and their ratio with some phenolic acids (mainly hippuric acid, 4ʹ-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, and 3-(4ʹ-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid)) was used by Fraga et al. [45] to classify individuals consuming orange juice into three different metabolic patterns. Note that subjects with a low or intermediate ratio (i.e., higher production of phase II metabolites) saw a significant reduction in body fat percentage and blood pressure after 60 days of orange juice consumption [45].

In other studies, authors did not define quantitative metabotypes for flavanone phase II metabolites, but consistently observed high CV% in their plasma concentrations or excreted amounts in urine, suggesting that some individuals are producing largely more phase II metabolites than other individuals [62,63,68,75,76,114]. Pereira-Caro et al. [62] reported CV% up to 300% in the urinary excretion of phase II flavanone metabolites in a study investigating the effect of exercise on flavanone metabolism after consumption of orange juice. Exercise did not significantly modify the mean amount of phase II flavanones in circulation. Recently, machine learning has been used to better understand the contribution of sex to the pool of flavanones and phenolic acids in circulation, both in plasma and urine, after chronic consumption of a maqui-lemon beverage [75,76]. Results accounted for an effect of sex on some metabolites,as naringenin-glucoside, homoeriodyctiol-glucuronide, eriodyctiol and its sulfate derivative, for certain individuals.

3.3.1.5. Anthocyanins

Data on IIV in the ADME of anthocyanidin metabolites have been mainly reported for cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, and petunidin, either as aglycones or phase II conjugates (Supplemental Table 3). Unspecific phenolic acids, such as phenylpropanoic, phenylacetic and benzoic acid derivatives, which can be originated by gut microbiota catabolism of anthocyanidins, have been reported in Supplemental Table 6. Regarding native anthocyanidin metabolites, a substantial variation in their plasma concentration and urinary excretion among individuals has been observed, as expressed by high CV% (continuous production), but to date no specific cause has been identified to explain the reported IIV (Supplemental Table 3). An attempt to review the factors that affect anthocyanidin bioavailability in humans has been recently done by Eker et al. [21], without reaching any firm conclusion due to a lack of literature addressing this topic. The authors assumed that differences in enzymes involved in anthocyanidin metabolism and transport and in gut microbiota composition and activity, which in turn can be affected by further factors such as genetics, age, and diet, may be the main responsible for IIV in anthocyanidin ADME [21]. However, more studies are needed to support these assumptions.

3.3.1.6. Isoflavones

Regarding isoflavones,IIV has been suggested for both unchanged compounds, mainly daidzein, genistein, glycitein, formononetin, and biochanin A, and for gut microbiota-derived catabolites, namely dihydrodaidzein, dihydrogenistein, equol, O-DMA, and 6ʹ-hydroxy-O-DMA (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 5). Equol has been the most studied compound for long and likely the first catabolite for which IIV was hypothesized in 1984 [115].

Differences among subjects have been described mainly in the production or non-production of equol and O-DMA (cluster production), the two main microbial-derived catabolites of daidzein. In fact, for both metabolites, two distinct metabotypes have generally been identified, clustering subjects between producers and non-producers. These observed metabotypes are determined by a specific gut microbiota composition and activity. It was reported that the gut microbes involved in equol production are more than ten, including Slackia equolifaciens, Slakia isoflavoniconvertens and Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, while, unfortunately, there are fewer reports on the bacterial species specifically linked to O-DMA production [9]. According to Zheng et al. [116], subjects with an equol-producing metabotype have a higher abundance of the equol-producing bacteria Adlercreutzia equolifaciens and Bifidobacterium bifidum, and a different microbial composition enriched in the genera Prevotella, Megamonas, Allistipes, Desulfovibrio, Collinsella, and Eubacterium. This is in agreement with the previous findings of Nakatsu et al. [117], who reported that post-menopausal women able to produce equol presented an enrichment in Bifidobacterium and Eubacterium compared to non-producers after one-week consumption of soy bars. Interestingly, Yoshikata et al. [81] identified equol-producing bacteria in 97% of women participating in their study, although only 22% of them were equol producers, suggesting that equol production might not depend on the quantity, but on the quality of equol-producing bacteria consortiums. In addition, equol producers presented higher microbiota diversity than non-producers, which might favour equol production.

The equol-producing and O-DMA-producing metabotypes are unrelated: the capacity to harbour equol-producing bacteria is not associated with the ability to harbour O-DMA-producing bacteria. The studied populations have displayed a distinct distribution of these metabotypes, but, in most cases, the proportion of equol-producers was below 50%, while that of O-DMA producers was above 50% of the population [79,80,82,83,47,[118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129]]. Nevertheless, a couple of recent reports seem to deny the existence of a specific O-DMA-producing phenotype, as O-DMA was found in urine of the 95% [46] and 100% [130] of German postmenopausal women and Spanish adults, respectively. Future studies will confirm whether O-DMA production is characterized by quantitative differences (high vs. low production, i.e., continuous production), instead of qualitative differences (cluster production), as previously believed. Ethnicity may also play an important role in the distribution of equol- and O-DMA-producing metabotypes, as observed for example by Song et al. [131] in a population of more than 300 Korean American and Caucasian-American female subjects. Equol-producer phenotype was significantly more prevalent in Korean American than in Caucasian American women and girls and, conversely, the O-DMA-producer phenotype was significantly less prevalent in Korean American than in Caucasian American females [131]. However, further investigation is needed to evaluate the role of ethnicity and dietary habits in the observed differences between sub-groups of individuals.

Some studies looked for associations between the incidence of the equol- or O-DMA-producing metabotypes and sociodemographic characteristics of the population other than ethnicity, including age and education level, anthropometric values (height, weight and BMI, among others) and lifestyle factors (as dietary habits) [54,80,81,83,120,[125], [126], [127],[132], [133], [134]]. No clear associations with any particular factor were consistently reported across all studies.

An increasing number of studies have associated equol- or O-DMA-producing metabotypes with potential effects on health, mainly related to protection against menopausal symptoms [79,133,135] and cardiovascular risk, as comprehensively reviewed by Frankenfeld (2017). Equol- and/or O-DMA-producers seemed to have better cardiovascular health profiles than non-producers [82,116,134,136]. In addition, acute vascular benefits of equol in men have been reported only in equol producers upon soy consumption. Interestingly, the same benefits were not observed in equol non-producers after intake of synthetic equol, suggesting that the microbial ecology associated with the equol-producing capacity is crucial for determining health benefits [137]. However, these results were not fully supported by other scientific evidence: the study by Usui et al. [121] described a significant improvement of cardiometabolic risk biomarkers particularly in equol non-producer females, after chronic daily oral administration of S-equol. Clarifying whether the health effects exerted by equol and/or O-DMA are due to the presence of a specific microbial ecology associated with their production or to the direct activity of the microbial metabolites themselves is needed, as well as understanding whether the health status has an impact on the production of these metabolites or are the metabolites that condition the health status [138].

Other isoflavone metabolites are produced by all individuals, although in different amounts (continuous production), as evidenced by high CV% values [58,117,124,129,132,[139], [140], [141]]. The factors responsible for the observed IIV have not been determined yet, and further studies are needed to elucidate them. Interestingly, unchanged isoflavone metabolites (in particular daidzein, genistein, and glycitein) are excreted in higher amounts in equol non-producers [119,134]. A recent work reported that the AUC0-24h and Cmax values of 5-hydroxyequol, but not of other isoflavone metabolites changed according to the enterotype, with subjects belonging to Prevotella-rich enterotype presenting higher values than in the Bacteroides and Ruminococcaceae enterotypes [142].

Recently, Soukup et al. [46] assessed the metabolic profile of isoflavones considering both daidzein and genistein, in 59 post-menopausal women consuming a soy supplement for 12 weeks. The study population was classified into 5 isoflavone metabotypes (cluster production), characterised by different proportions of daidzein, genistein, equol, dihydrodaidzein, dihydrogenistein, and 4-ethylphenol. Insterestingly, clusters were associated with estrogenic potencies. This study opened the door to more comprehensive metabotyping approaches for soy isoflavones, avoiding reductionist approaches focused on just equol or O-DMA.

3.3.2. Non-flavonoids

3.3.2.1. Phenolic acids

Phenolic acid metabolites can originate from human metabolism or from resident microbiota catabolism of phenolic acids occurring in foods, namely hydroxycinnamic and benzoic acid derivatives, as well as from gut microbial catabolism of dietary flavonoids [20]. It is noteworthy that some of them can also derive from the metabolism of aromatic amino acids, or from a few endogenous metabolites such as dopamine. Phenolic acids can also undergo subsequent phase II metabolism. In this class, data on IIV has been reported, mainly for cinnamic, phenylpropanoic, phenylacetic, benzoic and hippuric acid derivatives, either as aglycones or phase II conjugates (Supplemental Table 6). Their plasma concentration and urinary levels are affected by a substantial IIV, as represented by the high CV%, up to 301%, as reported in Supplemental Table 6 (continuous production) [59,63,68,72,74,78,84,91,143]. This may indicate that some factors can dramatically affect their production in every single individual, or that high and low producers of these metabolites exist. Indeed, some studies focused on flavonoids and reporting on phenolic acids have discussed the role of phenolic acids for classifying subjects according to metabolic patterns (cluster production) [55,43,42,45]. As an example, phenylpropanoic acids, in particular 3-HPPAs, have proved to be fundamental for the determination of colonic metabotypes of flavan-3-ols, showing different production patterns associated with PVL production [33,55,43,42]. Similarly, when subjects following a free-diet supplemented or not with cranberry powders were clustered according to their phenolic metabolite profiles, three metabotypes characterized by quali-quantitative differences in the excretion of some metabolites were identified: one metabotype presented a high excretion of PVLs; another metabotype showed high excretion of several low molecular weight phenolic metabolites belonging to cinnamic, phenylpropanoic, phenylacetic, and benzoic acids, benzaldehydes and benzene diols (catechols); and the third metabotypes was characterized by a low phenolic metabolite excretion [55]. Whether these phenolic profiles may be related to specific gut microbiota profiles or other drivers of IIV is unknown. Such metabotyping approach considering several classes of phenolic compounds pointed out the importance of phenolic acids when classifying individuals consuming phenolic-rich products or not following any specific dietary treatment.

The excretion of a few phenolic acids (mainly hippuric acid, 4ʹ-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, and 3-(4ʹ-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid)) served, together with their excretion ratio to phase II flavanones, to classify orange juice consumers into three groups (low, medium, and high excretors) and explore the benefits of orange juice on subjects presenting different patterns of metabolism [45]. As phenolic acids contribute to a large extent to the total amount of (poly)phenols in circulation, investigating different phenolic acid production patterns may help better understand the role of (poly)phenols on human health.

Specific factors influencing IIV related to phenolic acid metabolites have not been clearly identified, although a certain role of the gut microbiota composition and microbial activity have been suggested [66,69,84,85,144]. The impact of age, BMI, and lifestyle factors, including dietary habits, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, are still not robustly characterised in available studies [33,75,76,85,145,146]. Bento-Silva et al. [20] recently reviewed the variables affecting IIV associated to phenolic acids, suggesting a major contribution of gut microbiota and genetic polymorphisms, however, without reaching any firm conclusion.

3.3.2.2. Hydrolysable tannins (mainly ellagitannins)

Regarding hydrolysable tannins, no literature dealing with IIV in the ADME/bioavailability of gallotannins was found, probably due to their rare occurrence in plant-based foods. Conversely, much information was found about ellagitannins, high molecular weight ellagic acid derivatives, with 32 studies reporting a marked IIV (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 7). This is likely related to the fact that metabotypes involved in the metabolism of ellagitannins/ellagic acid, characterized by the production or not (cluster production) of specific gut microbiota-derived metabolites, namely urolithins, were first described many years ago and have subsequently been the subject of in-depth studies [48,49,[147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153]]. Three metabotypes have been consistently described: urolithin metabotype A includes producers of only urolithin A (3,8-dihydroxy-urolithin), urolithin metabotype B includes producers of isourolithin-A (3,9-dihydroxy-urolithin) and urolithin-B (3-hydroxy-urolithin) in addition to urolithin-A, whereas urolithin metabotype 0 identifies non-producers.

All the available information on IIV in the production of ellagitannin/ellagic acid metabolites, that mainly concerns urolithin metabotypes, the microbial species involved in urolithin production (Gordonibacter pamelaeae, Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens, and Ellagibacter isourolithinifaciens), and other determinants (such as age, BMI, and (patho)physiological status) involved in their distribution, as well as the potential relationships with human health, has already comprehensively been reviewed and updated by Tomás-Barberán et al. [152] and García‐Villalba et al. [154], thus it is not further discussed in this review.

3.3.2.3. Lignans

The main lignan catabolites enterolactone and enterodiol, and in a few cases the native compound secoisolariciresinol, are the compounds for which an IIV in their production has been observed (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 8). Enterolactone is the most frequently assessed catabolite. Two quantitative phenotypes have been mostly described, namely high and low enterolactone producers (continuous production) [86,50,51,155] and different criteria (top 10% or above median) have been used to define high producers.

Hålldin et al. [22] recently reviewed the factors that may affect human plasma concentration of enterolactone and concluded that the composition and activity of the intestinal microbiota appear to be the most critical determinants associated with IIV, followed by the use of antibiotics. Enterolactone is produced by the gut microbiota, starting from plant lignans, through a series of deglycosylation, demethylation, dehydroxylation, and dehydrogenation reactions, catalysed by a consortium of bacteria. Some bacterial genera have been identified and associated with each step: Bacteroides and Clostridium with deglycosylation, Eubacterium, Butyribacterium and Blautia for demethylation, Clostridium and Eggerthella for dihydroxylation, and the species Lactonifactor longoviformis for dehydrogenation. Consequently, the lack of certain bacteria, their interaction, or an inappropriate intestinal environment could decrease enterolactone production, determining the different metabotypes [22]. Intake of lignan-rich food, constipation, BMI, sex and other lifestyle factors, as smoking, could also influence the total variability among subjects [22,156]. Regarding the health implications of different levels of enterolactone production, not much has been reported yet [22]. A high enterolactone production may be related to better anthropometric parameters [86]. Interestingly, a gene expression analysis in fecal exfoliated cells has recently revealed that high enterolactone production was associated with a suppressed inflammatory status [50].

Besides enterolactone, enterodiol is a peculiar microbial catabolite of lignans. Nowadays, it is not clear if high and low producer phenotypes can be clearly discriminated for enterodiol as well, but undoubtedly its production, as well as secoisolariciresinol metabolism, is affected by a high IIV, as shown by a high reported CV% (continuous production) (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 8). Whether high enterolactone producers are also high enterodiol and secoisolariciresinol producers remains to be established.

3.3.2.4. Stilbenes

IIV has been reported for unchanged compounds, namely trans-resveratrol (3,5,4ʹ-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) and piceid (resveratrol-3-glucoside), and for glucuronide derivatives of trans-resveratrol and its gut microbiota-originated catabolites (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 8). Trans-resveratrol is a metabolite that can be found in plasma of all subjects, but in different amounts, as indicated by a high CV% [157,158]. At the same time, its glucuronide derivatives seem to be selectively produced only by some subjects, as described in the study by Vitaglione et al. [159]. However, this observation would need further assessment.

Regarding gut microbiota-derived catabolites, Bode et al. [53] described different routes of microbial conversion of trans-resveratrol: one leading to the production and excretion of dihydroresveratrol, another one producing lunularin and a third one leading to an equivalent production of both catabolites. In detail, lunularin, also known as 3,4ʹ-dihydroxybibenzyl, is a trans-resveratrol catabolite obtained by its reduction to dihydroresveratrol and subsequent dehydroxylation at the 5-position. Almost all lunularin producers also excreted 3,4ʹ-dihydroxy-trans-stilbene [53]. Thanks to additional in vitro experiments within the same study, Bode and colleagues found an association between dihydroresveratrol production and an intestinal microbiota enriched in Slackia equolifaciens and Adlercreutzia equolifaciens [53]. The non-production of dihydroresveratrol was associated with a greater presence of Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia and Cyanobacteria [53].

Iglesias-Aguirre et al. [52] have recently described the consistent observation of two metabotypes associated with resveratrol catabolism: 195 healthy individuals have been clusterized as lunularin producers and non-producers, similarly to what Bode et al. [53] previously observed both in vitro and in vivo in a smaller population of 12 individuals. In the population studied by Iglesias-Aguirre et al. [52], 74.4% of individuals were lunularin producers and among them, high, medium and low producers were defined. In addition, lunularin producers selectively excreted two additional catabolites, namely 4-hydroxydibenzyl and 3,4ʹ-dihydroxy-trans-stilbene. The lunularin non-producer metabotype was significantly more prevalent in females, but independent of individuals’ BMI and age. Even if these are interesting results, further research is needed to confirm lunularin metabotypes, the role of gut microbiota composition in its production, and the possible impact on health.

3.3.2.5. Other (poly)phenols

Concerning other (poly)phenol sub-classes, it is worth mentioning IIV in the metabolism of hop prenylflavonoids, particularly isoxanthohumol. Isoxanthohumol microbial catabolism allows the classification of individuals into poor, moderate and strong producer phenotypes (continuous production) of 8-prenylnaringenin [58,54,160]. These three quantitative metabotypes could be linked to differences in gut microbiota composition (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 8).

Regarding IIV in alkylresorcinol and oleuropein metabolism, sex may influence it, based on available studies [161,162]. In particular, for both classes, continuous production of catabolites was observed, with women presenting higher AUCs for the two main end products of alkylresorcinol catabolism, namely 3,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid and 3-(3ʹ,5ʹ-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoic acid [161]. On the contrary, men showed higher AUCs for conjugated metabolites of hydroxytyrosol after intake of an olive leaf extract, independently of the oleuropein dose and the administration format [162].

Last, the colonic metabolism of oat avenanthramides into dihydro-avenanthramides may not be completed in all individuals as this transformation depends on the presence of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [163]. This preliminary observation was achieved in a small sample set of 13 healthy subjects, but was supported by both human faecal fermentations and gnotobiotic mice experiments.

3.3.3. Determinants of inter-individual variability in (poly)phenol bioavailability

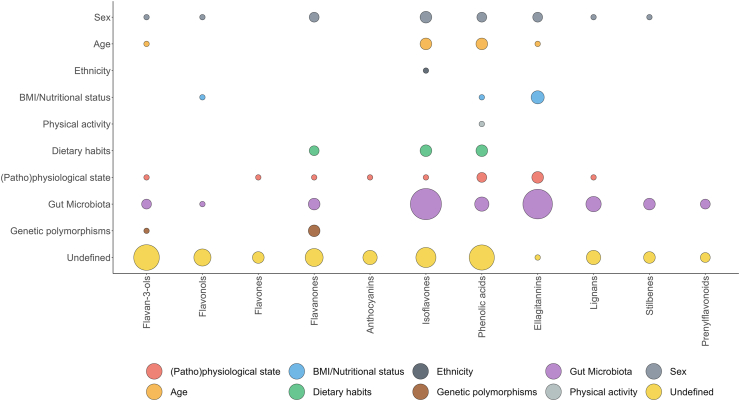

The scientific literature considered so far highlighted that even if the inter-individual differences in the metabolism and absorption of phenolic compounds are frequently observed and reported, the factors underlying these differences are mainly undefined, particularly for some sub-classes of flavonoids and phenolic acids (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Factors driving the inter-individual variability in the ADME of main phenolic classes. The size of the circle accounts for the number of studies. BMI, body mass index.

An influence of genetic polymorphisms in phase I/II enzymes and transporters has been reported for flavanone metabolites [44,109,110], and suggested for flavan-3-ol metabolites [33,35,42], based on different excretion patterns of sulfate and glucuronide derivatives among individuals. In this latter case, different data pre-treatment methods proved fundamental to unravel inter-individual differences in the production of phase II flavan-3-ol metabolites [42]. These results suggested that diverse pre-treatments, as well as clustering methods (density- versus distance-based), are fundamental to explore inter-individual differences and their potential causes [42].

The gut microbiota composition and its functionality emerged as the primary determinant for IIV in the metabolism and bioavailability of isoflavones, ellagitannins, and lignans (Fig. 4). The microbiota undoubtedly plays a key role also in the inter-person differences in the production of gut microbiota-derived catabolites of all other flavonoid classes, phenolic acids, stilbenes and other minor (poly)phenol sub-classes, although the specific bacteria and conditions responsible for the observed differences still have to be clarified. Indeed, many works where the source of IIV was classified as “undefined” are likely related to differences in the gut microbiota composition, but evidence of this still has to be provided. Faecal fermentation studies may be of help in classifying individuals according to the microbial metabolism of specific phenolics, as recently done for some flavan-3-ol monomers and avenanthramides [[163], [164], [165]].

Sex, age, ethnicity, BMI and nutritional status, physical activity, dietary habits, and (patho)physiological status may condition the metabolism of some phenolic classes, but, in general, they do not seem to influence too much phenolic metabolism. Data are lacking for most classes of phenolics, but for some, scattered data are available. For instance, for ellagitannins, age, sex, nutritional and health status have been described to be relevant sources of IIV in the production of urolithins [48,49,149], while ethnicity may be involved in a different production of equol/O-DMA from isoflavones [131]. (Fig. 4). Sex may also drive the metabolism of flavanones [75,76]. Studies comparing different classes of phenolic metabolites may help to better understand the drivers of the inter-person variation in the ADME of (poly)phenols. An example is the work by Hidalgo-Liberona et al. [77], who showed that a healthy intestinal barrier favours phenolic bioavailability compared to impaired intestinal permeability.

3.4. Study limitations, gaps, and recommendations

Although more than 150 studies were found and examined in this systematic review, it is clear that the way in which IIV in ADME of (poly)phenols has been studied so far has major limitations and that future studies on the topic should certainly adopt new methodological practices.

Most of the studies were conducted with a limited number of participants, and IIV was usually a post-hoc observation rather than an a priori outcome. The lack of focus on this phenomenon clearly driving the overall bioavailability of (poly)phenols and likely conditioning their health effects at the individual level, may hamper the achievement of robust findings for these plant bioactives. This highlights the need to include an adequate number of participants in intervention studies and look for specific associations between ADME/bioavailability of (poly)phenolic metabolites and potential IIV determinants, such as age, sex, genetic polymorphisms and gut microbiota, among others.

The works conducted for some classes like ellagitannins and isoflavones may be a benchmark for designing future initiatives with other phenolic classes, even if their presence in a limited number of foods occasionally consumed helps to conduct intervention studies that are feasible for volunteers (i.e., that not imply to refrain from eating plant-based foods and beverages for days). Differently, it becomes more difficult to carry out such intervention studies for major dietary phenolics like flavan-3-ols and hydroxycinnamic acids, as they are widespread in plant-based foods and beverages and this implies adhering to strict (poly)phenol-free diets that are often a burden for study participants. Also for this reason, studies that consider many (poly)phenol sub-classes at the same time and assess IIV in the production of their metabolites/catabolites, trying to define broader phenolic metabotypes and the determinants involved, are missing. Just a few examples have been published in the literature, focused on cranberry [55] or wine [56,57] phenolic metabolites, in which volunteers were clustered on the base of the type and/or amount of phenolics excreted beyond the metabolic pathway of a single family of dietary (poly)phenols. Another very recent example is the administration of a supplement containing ellagitannins/ellagic acid, resveratrol, and isoflavones to 127 healthy adults, where up to 10 different combinations of urolithin-, lunularin- and equol-producing and non-producing metabotypes were found to coexist in the studied population [130]. This kind of comprehensive approach has also been recently applied in a study conceived by Mena and colleagues [166]. Briefly, 300 healthy volunteers (18–74 y) have been asked to perform a standardised oral (poly)phenol challenge test, consisting in an acute supplementation of several classes of dietary (poly)phenols. To assess the individual urinary excretion of phenolic metabolites, urine samples have been collected in fasting conditions the day after the challenge and, for some participants, for 24 h. This will allow to define aggregate phenolic metabotypes and assessing the associations in metabotype formation among different classes of (poly)phenols. Subjects’ information on dietary habits, smoking, physical activity, sleeping, anthropometric measures, health status, cardiometabolic risk, genetics, and gut microbiota composition have been collected to understand the determinants of the inter-individual variability [166]. Once published, this study may help to shed light on many of the questions arisen in this review.

The use of data-driven approaches to decipher the main determinants explaining IIV may be in fact very useful when dealing with complex datasets. In this sense, machine learning, like in the case of the study by Hernández-Prieto and colleagues [75,76], and other statistics or artificial intelligence approaches will have to be explored. They may be particularly relevant when dealing with samples and data from large intervention trials with massive data collection.

We should also be aware of the potential lack of relevance of the identified metabotypes in the future, as they may depend on instrumental limits of detection or the statistical approaches followed for their definition in a specific sample population. Moreover, what still needs to be proven for many families of (poly)phenols is the replication of the observed metabotypes and their stability over time, as these data are missing (except for isoflavones and ellagitannins) [9,52,130,138].

Lastly, adequate data reporting is essential to properly demonstrating and handling IIV. Due to the lack of guidelines in the field, the COST Action POSITIVe provided some recommendations for better designing and reporting studies dealing with IIV [41]. They also developed the “POSITIVe quality index”, a valid, reliable, and responsive score including 11 reporting criteria (sample size-power calculation, data distribution, p value, effect size, general characteristics of the subgroups where IIV was evaluated, data reporting for end-points by subgroups, measures of central tendencies and dispersion parameters, outliers, tables, graphs, presentation of full data and population characteristics) to assist the research community while describing IIV. The use of this index is quite anecdotal to date, but the adherence to it is encouraged to improve the quality of the evidence published.

4. Conclusions

IIV in the metabolism and bioavailability of (poly)phenols is a fact. Its specific determinants are somehow clear for isoflavones and ellagitannins, while they have not yet been defined, but only hypothesized, or insufficiently characterised for the majority of phenolic sub-classes. The gut microbiota plays a major role in the inter-individual differences existing in the ADME of most (poly)phenols. Genetic polymorphisms for enzymes associated with (poly)phenol metabolism may also play a role in some phenolic sub-classes. The information on the contribution of sex, age, ethnicity, BMI, nutritional status, physical activity, dietary habits, and (patho)physiological status to the inter-person variability is scarce and scattered among phenolic sub-classes.

Two major types of IIV in the bioavailability of (poly)phenols were observed: continuous or cluster-based metabolite production. The most common patterns of IIV are associated with continuous production of metabolites (all the subjects produce the same metabolites but in different amounts), where some groups of low, medium or high excretors can be identified using various criteria (below/above median, top 10%, etc.). These patterns have been reported for all flavonoids, phenolic acids, prenylflavonoids, alkylresorcinols, and hydroxytyrosol. Cluster production can be achieved discriminating subjects based on their different ability of producing or not specific metabolites (qualitative differences, producers vs. non-producers), as in the case of ellagitannins -urolithins-, isoflavones -equol and O-DMA-, resveratrol -lunularin-, or preliminarily for avenanthramides -dihydro-avenanthramides-, or based on quali-quantitative metabotypes (when subjects produce different proportions of the same pool of metabolites), as defined for flavan-3-ols -phenyl-γ-valerolactones and 3-HPPA-, flavanones -ratio phenolic acid/phase II conjugates-, and isoflavones -daidzein, genistein and their colonic metabolites-. In most of the cases, what still needs to be verified is the replication of metabotypes for many families of (poly)phenols and their stability over time.

IIV is usually assessed in relation to individual phenolic sub-classes and hardly ever takes into account the whole spectrum of phenolic metabolites produced from a foodstuff or a diet, precluding the investigation of different patterns of (poly)phenol metabolism and limiting the possibility of drawing sound conclusions on its determinants. Future studies, designed to comprehensively assess the metabolism of (poly)phenols, collecting as much information as possible about individuals (dietary and lifestyle habits, microbiota composition, genetics data, etc.) and taking into account the whole set of phenolic metabolites found in biofluids, may help to identify and define broader phenolic metabotypes and their determinants. The actual relevance of these phenolic metabotypes will then have to be determined through specific associations with health-related outcomes.

Funding