Summary

Dementia is highly prevalent in Japan, a super-aged society where almost a third of the population is above 65 years old. Japan has been implementing ageing and dementia policies since 2000 and now has a wealth of experience to share with other nations who are anticipating a similar future regarding dementia. This article focuses on the 2019 National Framework for Promotion of Dementia Policies that, based on its philosophy of Inclusion and Risk Reduction, lays out five complementary strategies. Together, these five strategies encourage a whole of society approach in dementia care. We first elaborate on the activities being undertaken under each of these strategies and then discuss the future challenges that Japan needs to address. These policy and social innovations spearheaded by Japan can be useful information for other countries that are anticipating similar future as Japan.

Keywords: Japan, dementia, policy, social innovation

Introduction

Dementia is a degenerative neurological disorder that affects an estimated 50 million people worldwide and is projected to double by 2030. Dementia impairs multiple cognitive abilities such as language, problem solving, general intelligence, orientation, and social abilities among others. Since 2000, Japan has seen rapid growth in its ageing population. Today, 65 years or older people comprise 29% of the population (1). With an ageing population, long-term cognitive diseases like dementia are on the rise and Japan has one of the highest rates of dementia in the world. Nearly 5 million Japanese people were living with dementia in 2015 (2). By 2025, one in 5 people in Japan is projected to have dementia and by 2060 one-third of the population will be afflicted by this condition (3). More recently, two simulation studies have applied updated assumptions of changing education level and cardiovascular health in elderly population in Japan, and reported that dementia cases will stay stable at around 5 million up until 2050 (4,5). In Japan, dementia caused approximately 182,077 deaths in 2016 (6) and in 2019 Alzheimer's disease was the leading case of mortality with 164,874 deaths (7).

The social burden of dementia is unquestionably high. The cost of dementia in Japan was 14.5 trillion Japanese Yen (JPY) (USD 107.3 billion) as estimated in 2014 and a single dementia patient can add JPY 5.95 million (USD 44,000) to the cost burden (8). The cost of home care was more than that of institutional care and the total cost of informal care was JPY 6.16 trillion (USD 45.6 billion). A microsimulation modelling study projected the costs of formal care to rise to USD 125 billion in 2043 and informal care to USD 103 billion for informal care (4). This indicates that a lot of the care burden falls on the families of people with dementia. Moreover, an overall shrinking population since 2011 means that there are fewer people to support the elderly, increasing the care burden on the youth.

Recognizing the rising burden of age-related health problems such as dementia, the Government of Japan has taken several steps and implemented health policies and social care initiatives to address the effects of dementia. In 2000, a landmark health system reform was made through the introduction of the Long-term Care Insurance Act (9). This insurance system intends to provide user-oriented care and support the independence of elderly people by providing generous coverage and benefits to people of all levels of income. Another crucial milestone for dementia was the thoughtful change of the Japanese word used for dementia from "Chiho" (fool) to "Ninchisho" (cognitive disorder) in 2004 (10) to address the stigma associated with the condition and also set the direction of the nationwide momentum. Table 1 presents the major policies enacted and events held in Japan to improve the care and quality of life of the people living with dementia and their families.

Table 1. Dementia supporting policies and events in Japan.

| Years | Policies and Events |

|---|---|

| 2000 | Long-term Care Insurance Act was enacted. It contributed to developing dementia care |

| 2004 | Japanese word to mean dementia was changed from "Chiho" to "Ninchisho" |

| 2005 | Dementia Supporter Program was started |

| 2014 | Legacy event in Japan following Dementia Summit in UK was held |

| 2015 | New Orange Plan was launched by 12 related ministries and agencies (revised in 2017) |

| 2017 | Revision of the Long-term Care Insurance Act |

| 2018 | Ministerial Council on the Promotion of Dementia Policies was set up |

| 2019 | National Framework for Promotion of Dementia Policies was adopted at the Ministerial Council |

The latest national framework for the promotion of dementia policies is a radical piece of work in setting a vision for a society where people living with dementia are valued as assets and not considered a burden. It demonstrates how policy innovation leads to social innovation. This framework can be useful for other nations that are, and would be, dealing with the rising incidence of dementia. This article provides a narrative overview of the 2019 National Framework for Promotion of Dementia Policies (11) and then discusses the future challenges for Japan that need further deliberation and innovative solutions.

National Framework for Promotion of Dementia Policies 2019

The underlying philosophy of this framework is "Inclusion" and "Risk Reduction" (11). Inclusion refers to living as one society irrespective of the presence or absence of dementia. Risk reduction means delaying the onset or progression of dementia. These two concepts are two sides of the same coin to realize a society where people can live their daily lives with dignity and hope, even after they are diagnosed with dementia. This framework incorporates the perspectives of people with dementia and their families to help develop people-centered services. There are five complementary strategies in the framework when combined can help to build such an inclusive society: i) Promoting public awareness and supporting efforts made by people with dementia to disseminate their stories and opinions to the public; ii) Prevention; iii) Medical care, nursing services, and support for caregivers; iv) Promoting the creation of barrier-free spaces and services for people with dementia and providing support to people with early-onset dementia; and v) Research and development, industrial promotion, global expansion.

These five strategies are elaborated below through examples of activities that are being implemented in Japan upholding the philosophy of Inclusion and Risk reduction.

Promoting public awareness and supporting efforts made by people with dementia to disseminate their stories and opinions to the public

Policies and social care initiatives are effective when there is proper public awareness about the problem, its effects, and support services. There are two notable programs currently being rolled out in Japan for raising awareness and providing community support to people living with dementia. The first one is the "Dementia Supporters" training program funded by the national budget. The program takes place mainly in the community, at workplaces such as the police station, and schools. As of June 2021, 13.3 million people have been trained as dementia supporters. The supporters are certified with orange bracelets as a token. In Japan, salespeople, bus drivers, and store staff working at the cashier are often seen with orange bracelets. Supplemental Figure S1 (https://www.globalhealthmedicine.com/site/supplementaldata.html?ID=68) depicts dementia support in training.

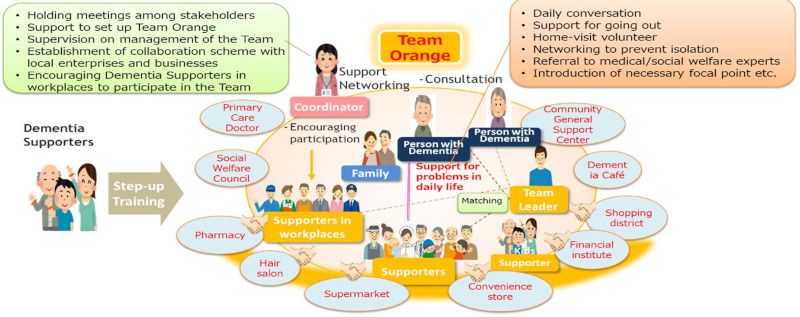

The second program is a community-based scheme known as Team Orange. This program aims to connect dementia supporters and health professionals to people with dementia and their families in the community. The government targets to set up 1,700 Team Orange at the municipality level nationwide by 2025. Team Orange facilitates early intervention to provide mental support and daily life support to those diagnosed with dementia. A coordinator is assigned to each team who coordinates with the person with dementia and connects them to appropriate resources. They also establish collaborations with local businesses such as hair salons, supermarkets, banks, and more where the people with dementia can then avail necessary services. The ecosystem of activities of Team Orange is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Team Orange activities. Source: Reference (10).

The other program to increase awareness about dementia in the community is the Dementia Hope Ambassadors. Here, people with dementia are assigned as ambassadors who share their experiences and views for dementia promotion and attend international meetings to introduce the Declaration of Hope. Also, more people with dementia spending time in public helps to eliminate discrimination and prejudice. In Supplemental Figure S2 (https://www.globalhealthmedicine.com/site/supplementaldata.html?ID=68), five ambassadors are seen at the launch event of the Dementia Hope Ambassadors.

Prevention

Preventive programs are critical in slowing the progression of dementia and operationlaise theme of Risk Reduction. The Kayoinoba program is set up for local residents with dementia (Figure 2). Various social activities and learning opportunities are organized by the residents for elderly people to stay active. Activities include exercising, dining, attending tea-party, and practicing their hobbies. Staying socially and physically active improves motor and oral functions, prevents deterioration of cognitive functions, and prevents undernutrition in people with dementia.

Figure 2.

Different ways Kayoinoba helps to delay the onset of dementia. Source: Reference (18).

Medical care, nursing services, and support for caregivers

Properly established medical and community care are vital for risk reduction by ensuring early detection and timely intervention. Dementia care providers are trained through multi-layered programs to enhance the care and support to the person with dementia in the community. Training is being given to 300,000 caregivers on basic principles, knowledge, and skills of dementia care. Around 50,000 caregivers are given "practice leader" training to lead dementia care teams and nearly 3,000 caregivers are given "dementia care leader" training (12). These leaders plan dementia care practitioner training and lead care quality improvement.

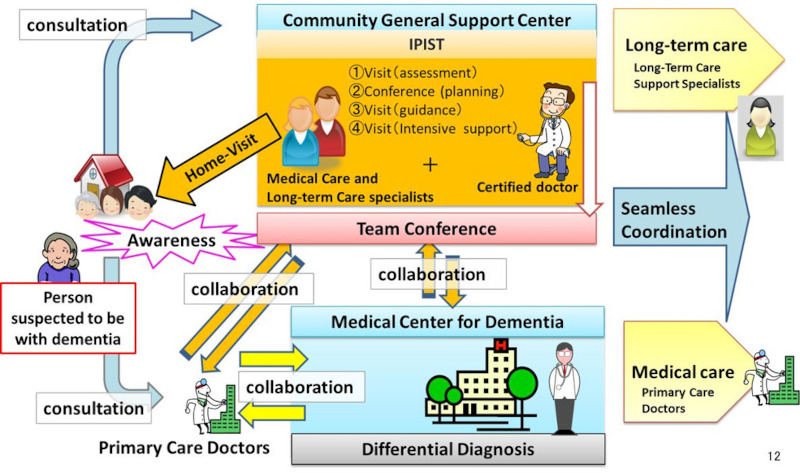

A streamlined collaboration and communication system has been developed between community care centers, primary care doctors, and long-term care support specialists (Figure 3). Activities range from home visits to raise awareness, investigate the situation of elderly people with dementia living alone who tend to face many difficulties, and early detection of people suspected to have developed dementia through care planning conference calls. When a person is diagnosed with dementia, an early intensive support team provides the initial care and then various players including medical professionals collaborate to provide coordinated care and support.

Figure 3.

A model of the collaborative care between community support groups, primary care doctors and long-term care support specialist. Source: Reference (19).

Japan is also in the process of building a community-based Integrated Care System by 2025 when the baby boomers will be 75 years old and above. This integrated system will comprehensively ensure the provision of dementia-responsive health care, nursing care, prevention, housing, and livelihood support. This would enable the elderly to live the rest of their lives in their own way in environments familiar to them, even if they become heavily dependent on long-term care. The progression status of this project varies from place to place. Ideally municipalities, as insurers of the Long-term Care Insurance System, as well as prefectures are required to establish the community-based Integrated Care System by utilizing local resources.

Besides these, it is known that informal caregivers such as family carers shoulder a major share of care responsibilities of people with dementia. To alleviate their burden through peer support, a unique approach known as Dementia Café has been implemented. A dementia café is where people with dementia and their families can gather (Supplemental Figure S3, https://www.globalhealthmedicine.com/site/supplementaldata.html?ID=68). As of 2020, Dementia Cafés are operated at almost 8000 places in 1,516 municipalities across the country (13). At the Dementia Café, families caring for a person with dementia discuss their concerns and exchange opinions. These cafés also provide opportunities for families and people with dementia to connect with society.

Promoting the creation of barrier-free spaces and services for people with dementia and providing support to people with early-onset dementia

A bold vision set by the framework is to establish a society where people with dementia can live without any barriers. To achieve this vision, the Dementia Barrier- Free program has been developed. Under this program, the Japan Public-Private Council on Dementia was formed in 2019. Nearly 100 organizations from economic organizations, financial sector (bank/insurance), transportation, life-related industries (retails), medical and welfare organizations, local governments, academic society, groups of persons with dementia, ministries, and agencies etc. joined the council. The council accredits and commends dementia-friendly companies. It also facilitates the development of dementia barrier-free products and services. Various members in the council cooperate to address long-term and burning issues around dementia such as frauds targeting people with dementia, traffic safety, and find solutions such as contractual assistance to people with dementia for making critical decisions.

Research and development, industrial promotion, global contribution

The framework not only focuses on guiding programs for the present day, but also promotes research and development (R&D) for the discovery of prevention and curative medicine. Moreover, R&D is also highlighted to continue to improve the understanding of mechanisms of the onset of progression of dementia and developing better methods for risk reduction, diagnosis, cure, rehabilitation, and long-term care model. These new approaches and methods will need to be validated and evaluated to ensure that they are working. Taking this into consideration, the framework also emphasizes establishing indicators of validation and evaluation for technologies, services, and devices for risk reduction and care of dementia.

Another forward-thinking component is the focus on establishing a registration system for research and clinical trials for people with dementia. Called the Orange Registry, this nationwide registry and collaborative system allows people with dementia to be observed throughout the clinical stages of the disease. The primary goal of the registry is to use the data accumulated to develop new treatments, medications, and care techniques for dementia from a range of patients including healthy individuals to those with preclinical stage, mild cognitive impairment, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and advanced stage dementia. These results will be used for early detection and response to dementia, establishing diagnostic methods, and developing fundamental treatments and preventive methods. Thus, this centralized system is expected to produce faster results in research and treatment. Lastly, the framework aims to promote and to globally expand the long-term care services model.

Challenges of Dementia Care in Japan

Despite the various policy and social care initiatives implemented by the Japanese government, there are still numerous challenges and limitations facing dementia policy and social care in Japan. People with dementia belong to society and need not be institutionalized for the remainder of their lives. This shift of their lives from hospitals and psychological institutions to the community is yet to be realized in full. To facilitate this process, as a society we need to see beyond the abilities lost because of dementia and utilize the residual abilities of the people with dementia. This mindset transformation needs constant messaging and enabling a dementia-friendly environment in the community and in the service industry.

Additionally, there is still a scope to develop intergenerational programs that will value the skills of the people with dementia and benefit the youth. Instead of making top-down policies for the people with dementia, it is important to discuss with the beneficiaries themselves and their families how they want to spend the remaining of their lives. It remains a challenge to get the beneficiaries engaged in Advanced Care Planning. Providing support not only to the people with dementia but also to the family and caregivers is essential. Dementia Café is one approach, but other effective avenues will need to be established such as providing financial support to the caregivers.

While comprehensive in guiding the development of systems for a better quality of life for those with dementia, the National Framework for Promotion of Dementia Policies 2019 lacks the life-course approach recommended for healthy ageing in general by the WHO (14). Even for dementia, it is now known that cognitive reserve is built during the early years of life and that mid-life behaviors and the environment profoundly impact when dementia will occur in one's life and how severe it will be (15). So, the risk reduction programmes in this framework will have to begin at gestation.

Conclusion

The rising threat of dementia in developed and developing countries alike needs anticipatory preparation of both the healthcare and the social systems. Japan's experience in implementing policies for healthy ageing and dementia provides valuable lessons and guidance to other countries to envision the changes that need to occur for successfully tackling a future with a high prevalence of dementia. Previous reviews of dementia policies have centered on the clinical aspects of dementia screening and management (16,17).

In this article, we highlighted the comprehensive way of thinking that Japan has launched through policy and social innovations for managing the dementia crisis. The 2019 National Framework for Promotion of Dementia Policies developed in Japan adopts a whole of society approach by considering multiple interweaving psychosocial, environmental, and healthcare aspects needed to reduce the risk of dementia and provide a better quality of life for those living with dementia. We have discussed some challenges that Japan has yet to address and devise appropriate solutions. Despite that, this framework's underlying philosophy of Inclusion and Risk Reduction is highly applaudable and can be adapted by other countries for their context.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Japan Population Census. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?toukei=00200524 (accessed June 9, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 2. Special Research of Health Labour Sciences Research Grant by Dr. Ninomiya, Kyushu University "Future projection of the population of the elderly with dementia in Japan", 2015. https://mhlw-grants.niph.go.jp/project/23685 (accessed August 16, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 3. Nakahori N, Sekine M, Yamada M, Tatsuse T, Kido H, Suzuki M. Future projections of the prevalence of dementia in Japan: Results from the Toyama Dementia Survey. BMC Geriatrics. 2021; 21:602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kasajima M, Eggleston K, Kusaka S, Matsui H, Tanaka T, Son BK, Iijima K, Goda K, Kitsuregawa M, Bhattacharya J, Hashimoto H. Projecting prevalence of frailty and dementia and the economic cost of care in Japan from 2016 to 2043: A microsimulation modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2022; 7:e458-e468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022; 7:e105-e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koyama T, Sasaki M, Hagiya H, Zamami Y, Funahashi T, Ohshima A, Tatebe Y, Mikami N, Shinomiya K, Kitamura Y, Sendo T, Hinotsu S, Kano MR. Place of death trends among patients with dementia in Japan: A population-based observational study. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:20235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Japan profile Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington; 2021. https://www.healthdata.org/japan (accessed June 9, 2023).

- 8. Sado M, Ninomiya A, Shikimoto R, Ikeda B, Baba T, Yoshimura K, Mimura M. The estimated cost of dementia in Japan, the most aged society in the world. PloS One. 2018; 13:e0206508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, Reich MR, Ikegami N, Hashimoto H, Shibuya K, Kawachi I, Campbell JC. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan's long-term care insurance policy. Lancet. 2011; 378:1183-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Trends in dementia policies about team orange. https://kouseikyoku.mhlw.go.jp/shikoku/chiiki_houkatsu/000247192.pdf (accessed June 9, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 11. Council of Ministers. Ministerial Council on the promotion of policies for dementia care. https://japan.kantei.go.jp/98_abe/actions/201906/_00049.html (accessed June 9, 2023).

- 12. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Outline of dementia policy promotion program implementation status. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/ninchisho_kaigi/pdf/r03taikou_kpi.pdf (accessed June 7, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 13. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Implementation of dementia cafes by prefecture. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000935275。pdf (accessed June 7, 2023) (in Japanese) .

- 14. World Health Organisation. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900 (accessed June 7, 2023).

- 15. Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004; 3:343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Traynor V, Inoue K, Crookes P. Literature review: Understanding nursing competence in dementia care. J Clin Nurs. 2011; 20:1948-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hampel H, Vergallo A, Iwatsubo T, Cho M, Kurokawa K, Wang H, Kurzman HR, Chen C. Evaluation of major national dementia policies and health‐care system preparedness for early medical action and implementation. Alzheimers Dement. 2022; 18:1993-2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Summary of the study group on promotion measures of general care prevention services, etc. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12300000/000576580.pdf (accessed June 12, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 19. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Outline for the promotion of dementia policies 2019. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000076236_00002.html. (accessed June 9, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 20. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. NPO Community Care Policy Network National Caravan Mate Liaison Council. Report on survey and research project on information dissemination to deepen society's understanding of dementia from the perspective of people with dementia (2017). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12300000-Roukenkyoku/80_tiikikea.pdf (accessed June 17, 2023). (in Japanese) .

- 21. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Current status of dementia cafes. https://kouseikyoku.mhlw.go.jp/kyushu/caresystem/documents/1221002.pdf (access August 14,2023) (in Japanese) .