Abstract

Lgl1 protein plays a critical role in neurodevelopment, including hippocampus, olfactory bulb, and Purkinje cell. However, the specific mechanism of LGL1 function in the midbrain remains elusive. In this study, we generated Lgl1 conditional knockout mice using Pax2-Cre, which is expressed in the midbrain, and examined the functions of Lgl1 in the midbrain. Histological analysis exhibited abnormal midbrain development characterized by enlarged ventricular aqueduct and thinning tectum cortex. Lgl1 deletion caused excessive proliferation and heightened apoptosis of neural progenitor cells in the tectum of LP cko mice. BrdU labeling studies demonstrated abnormal neuronal migration. Immunofluorescence analysis of Nestin demonstrated an irregular and clustered distribution of glial cell fibers, with the adhesion junction marker N-cadherin employed for immunofluorescent labeling, unveiling abnormal epithelial connections within the tectum of LP cko mice. The current findings suggest that the deletion of Lgl1 leads to the disruption of the expression pattern of N-cadherin, resulting in abnormal development of the midbrain.

Keywords: Lgl1, Midbrain, N-Cadherin, Migration

Highlights

-

•

We established Pax2-LGL1−/− conditional knockout mice and found abnormal midbrain development characterized by dilated ventricular aqueduct and thinning tectum cortex.

-

•

Lgl1 deletion disrupted the adhesion junction, leading to a loss of cell polarity among neuroepithelial cells. Consequently, the cellular arrangement in the early midbrain displays a loosely organized structure and cell shedding, subsequently leading to obstruction of the aqueduct. Accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid and an increase in pressure resulted ventricular aqueduct expansion.

-

•

Loss of Lgl1 disrupts adhesive connections, leading to aberrant glial cell arrangement, subsequent abnormal neuronal migration, and ultimately resulting in abnormal tectum development.

1. Introduction

During the neurodevelopment, newly generated neurons primarily detach from the surface of the ventricle, then migrate to their final destinations where they become part of an appropriate lamination and neuronal circuit [1]. Abnormal neuronal migration has been linked to a range of human neuropathic conditions, including periventricular nodular ectopia and autism spectrum disorders [[2], [3], [4]]. Consequently, the proper execution of neuronal migration is crucial for the structural arrangement and functional interconnection of the nervous system [5].

The establishment of cell polarity is an essential prerequisite for the process of neuronal migration, which is facilitated by alterations in the cytoskeleton and a complex network of cell adhesion receptors that are regulated by various molecules [6,7]. The migration pathway of neurons, whether radial or tangential, is determined by their specific origin within the developing nervous system. During radial migration, newly formed neurons traverse perpendicular tracks along the neuroepithelium's surface, utilizing radial glial fibers as their means of advancement [8]. Conversely, the tangential migration of neurons occurs in a parallel fashion to the pial surface.

Lethal giant larvae (Lgl) protein is an evolutionarily conserved and widely expressed cytoskeleton protein in Drosophila [9], which is essential for the establishment of epithelial polarity [10,11]. In this article, we have conditionally ablated the Lgl1 gene in the midbrain by crossing Lgl1(Flox/Flox) mice with Pax2-Cre to analyze the role of Lgl1 in midbrain development in mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Homozygous LP cko mice were generated by crossing Lgl1 Flox/Flox (Klezovitch et al., 2004) with Pax2-Cre mice (Ohyama and Groves, 2004). Pax2-Cre activity was expressed in the developing mesencephalon and metencephalon. The embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5) was defined as the day when the vaginal plug was found in the vagina, and the postnatal day 0 (P0) was the day of mouse birth. All animal management and experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the Shandong University of Chinese Medicine Ethics Committee. To identify wild type (WT), heterozygous, and homozygous (HOMO) mice, DNA was extracted from the tail for PCR analysis.

2.2. Histology and immunohistochemistry

Perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was performed on WT and HOMO mice following pentobarbital sodium anesthesia. Subsequently, the brain was completely isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Dehydration was then carried out using an ethanol series, ranging from 30% to 100%. For microscopic analysis and pathological observation, the samples embedded with the proper orientation in paraffin were sectioned at 7 μm thickness and stained using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Frozen sections were prepared by initially fixing the samples in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 3–4 h, followed by infiltration with 30% sucrose (in PBS) at 4 °C overnight. The specimens were then embedded in OCT compound and frozen at −20 °C using liquid nitrogen. Subsequently, tissue blocks were either sectioned at 7 μm or stored at −40 °C. Immunofluorescence staining was performed according to the standard staining procedures with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-Cyclin-D1, rabbit anti-N-Cadherin, mouse Nestin. The secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 593/488-labeled goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 1:300) and Alexa Fluor 593/488-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 1:300).

For the purpose of quantitative analysis, at least three confocal optical sections were examined from distinct animals for each genotype. At least three fields were randomly selected in each section across all midbrain regions. The density of positive cells was determined by conducting a cell count and subsequently normalizing the count to an area unit measuring 100 μm2. The quantification of relative fluorescence signal intensities was performed using the Image J software.

2.3. TUNEL

The TUNEL assay was conducted using the TUNEL detection kit ((Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany)) according to the instructions. The assessment of the apoptotic index in midbrain involved quantifying the density of TUNEL-positive cells within a defined area (100 μm2).

2.4. Bromodeoxyuridine labeling

The pregnant mice were intraperitoneally injected with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) at a dosage of 100 μg/g body weight. After 24 h, embryos were collected and the midbrain tissue were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4 °C. Frozen midbrain sections were made and subsequent experiments were performed according to the BrdU kit instructions. BrdU stained cells were counted using Image J software. The number of migrating cells in the midbrain of WT mice was normalized.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test between the two groups. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Conditional deletion of Lgl1 from the midbrain

To specifically knockout Lgl1 in the midbrain, we crossed Lgl1(Flox/Flox) mice with Pax2-Cre transgenic mice to inactivate Lgl1 in this region. The homozygous (HOMO) mice were viable and exhibited a more prominent arch in the cranial arc of the midbrain (Fig. 1A). These LP cko mice were more emaciated, displaying smaller body size and lighter weight (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence results confirmed the removal of LGL1 from the midbrain (Fig. 1C-E’).

Fig. 1.

Generation of LP cko mice mediated by Pax2-Cre transgenic mutation. (A) The overall appearance of WT and LP-cKO mice. (B) Weight curves of the control and LP-cKO mice. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, ***P < 0.001. (C–E) Immunofluorescence staining was performed on sagittal frozen sections of the midbrain of E13.5 WT and HOMO using anti-Lgl1 antibody. Nuclear marker DAPI was used for counterstaining (blue). (C′-E′) Lgl1 was efficiently deleted in the midbrain of HOMO mice. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

3.2. Structural midbrain abnormalities in LP cko mice

To determine early midbrain development was altered in LP cko mice, we examined Overall structure of the E12.5 embryo (Fig. 2A and 2A′). LP cKO mice exhibited higher cranial tops in the midbrain region from the E12.5 days. The H&E-stained midsagittal sections revealed aberrations in the mutant midbrain, characterized by clusters of cells exhibiting loss of polarity and absence of discernible apical membrane domain (arrows in Fig. 2B’). By E16.5, a distinct parietal membrane domain emerged in the midbrain, while a significant dilation was observed in the aqueduct of LP cko embryos (Fig. 2C'). We proposed that the cellular arrangement in the early midbrain exhibited loose organization, potentially leading to cell shedding and subsequent obstruction of the aqueduct. The resulting accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid and subsequent increased in pressure coincide with ventricular aqueduct expansion.

Fig. 2.

Abnormal development of the midbrain in LP cko mice. (A, A′) General appearance of E12.5 embryos. Note dome-like appearance of the head of the LP cko embryo. Magnification, × 1.5 (B, B′) Sagittal section of the midbrain of E12.5 embryo. Red arrows indicate the disordered arrangement of cells in the aqueduct of the midbrain and expanding over the cells that maintain cell polarity. (C–G′) Histologic appearance of midbrain from control (C–G) and LP cko (C′–G′) at different age. Scale bar represents 500 μm. (H) Line graph of the midbrain length in control and LP-cKO mice. (I) Line graph of the cerebral cortex thickness of midbrain in control and LP-cKO mice. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To determine whether postnatal midbrain development was also altered in LP-cKO mice, we examined histological sections of the midbrain. The midbrain aqueduct lengthening from rostral to caudal, concomitant with the disappearance of cellular disorganization within the aqueduct. Simultaneously, there was a decrease in radial width of the tectum at postnatal days 3 (Fig. 2D and D'), postnatal days 9 (Fig. 2E and E'), postnatal days 21 (Fig. 2F and F'), and postnatal days 42 (Fig. 2G and G').

To further investigate the impact of Lgl1 deletion on postnatal midbrain development, we conducted a detailed analysis of histological sections. Our findings revealed significant alterations in the midbrain structure and organization. Firstly, we observed a remarkable lengthening of the midbrain aqueduct from its rostral to caudal regions in LP-cKO mice, but the cellular disorganization within the tectum was disappeared, indicating improved structural integrity during postnatal development. Additionally, we noticed a noticeable reduction in tectum thickness compared to control mice at postnatal days 3, 9, 21 and 42 (Fig. 2D–G’). Loss of Lgl1 disrupted cell polarity in the aqueduct during embryonic development; however, this disruption was partially compensated for as the embryo matures. Nevertheless, the aberrant midbrain development resulting from Lgl1 loss persisted into adulthood without resolution, underscoring the crucial role of Lgl1 in midbrain development.

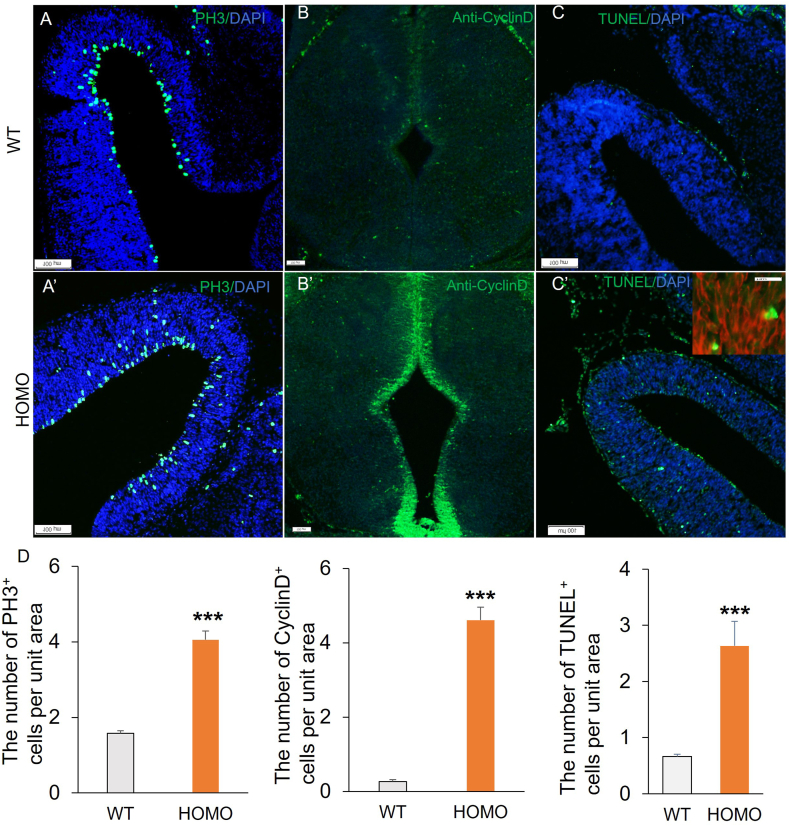

3.3. Activation of proliferation and increase in apoptosis in the LP cko neural progenitor cells

To investigate whether Lgl1 deletion changes in cell proliferation, we conducted immunostaining with antiphospho-histone 3 (PH3) antibodies to characterize mitotic cells (Fig. 3A, A′). The results showed that PH3-positive cells were dispersed throughout the tectum in LP cko midbrains, and the number increases relative to the WT (Fig. 3D). The detection of cell proliferation has also utilized antibodies against CyclinD (Fig. 3B, B’), and the overexpression of Cyclin D can result in uncontrolled cell proliferation. At E15, the fluorescence intensity of Cyclin D was significantly higher in the tail end of aqueduct of LN-cKO embryos compared to WT embryos (Fig. 3D), indicating a pronounced increase in cell proliferation.

Fig. 3.

Abnormalities of cell proliferation and apoptosis in the tectum of Lgl1 cKO mice. (A, A′) Immunostaining of sagittal sections from E14.5 WT tectum with anti-PH3 antibodies (red) reveals increase in mitotic cells in the tectum of LP cko mice. (B, B′) Immunofluorescence staining with Cyclin-D (green) on coronal sections of the midbrain from E13.5 mice demonstrated a significant increase in the number of proliferating cells in LP cko mice compared to their WT counterparts. (C, C′) Increased number of apoptosis cells in the tectum of LP cko mice. HOMO have more TUNEL-positive (green) cells than the WT mice. DNA is counterstained by DAPI (blue). The inset in C′ shows prominent localization of TUNEL+ cells (green) to the Nestin positive rosettes (red) in the LP cko tectum. (D) Statistically significant differences are indicated. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

To determine whether loss of Lgl1 led to changes in apoptosis, we performed TUNEL staining on sections of the embryonic midbrain at E14.5 (Fig. 3C, C′). A higher number of TUNEL positive cells was observed in the HOMO midbrain compared to the WT mice (Fig. 3D). The apoptotic cells in the HOMOs were localized to the neural progenitor cell domain and were abundantly present in the Nestin-positive, rosette-like structures (Fig. 3C’, inset). Therefore, loss of Lgl1 causes not only expansion of proliferating progenitor cells, but also their apoptotic cell death.

3.4. The neuronal migration defects in LP cko tectum

Neuronal migration is an essential process in tectum development. To examine whether neuronal migration was affected, dividing cells were labeled with BrdU, and their positions were examined after labeling for 24h. The early-born neurons at E12.5 were labeled with BrdU, and their position was examined at E13.5 (Fig. 4A, A′). In Lgl1-deficient tectum, most BrdU-labeled postmitotic cells 24 h later were scattered in the ventricle area and could not form a significant migratory cell stream (the dashed area in Fig. 4C’). However, the BrdU-labeled cells in tectum of WT mice have formed a typical migratory cell zone, which migrated from the ventricle region to the cortex (the dashed area in Fig. 4C). Thus, loss of Lgl1 in the tectum caused an impaired neuronal migration.

Fig. 4.

Impaired neuronal migration in LP cko mice during midbrain development. Sagittal sections of tectum immunostained with anti-BrdU antibody. BrdU was labeled at E12.5 (A, A′), and examined at E13.5. In control mice, most cells labeled with BrdU E13.5 migrated away from the VZ and the SVZ and reached the CP. Disrupted radial glial scaffold in LP cko. (D-F′) Nestin immunostaining (green) in radial glial cells at E12.5. DAPI (blue) was used to counterstain nuclei. Nestin was regularly radially arranged in WT mice (white arrows in F). The radial glial fibers show a chaotic pattern and gather in clusters in LP cko mice (white arrows in F′). (G-H′) Immunofluorescence co-staining was performed using adhesion marker antibodies N-cadherin (red) and DAPI (blue). The adhesion pattern of WT mice on the aqueduct surface was characterized by a linear and smooth configuration. However, the adhesion integrity of specific aqueduct regions started to deteriorate in E13.5 LP cko mice. H and H′ correspond to the highly magnified sections of areas in dotted lines in G and G’. Scale bar represents 100 μm (A-C′), 50 μm (D-F′), 200 μm (G-H′). (I) Quantification of the experiments shown in C and C’. (J) Quantification of the experiments shown in D and D’. Analysis of relative fluorescence intensity revealed an increased level of Nestin. (K) Quantification of the experiments shown in E and E’. Analysis of relative fluorescence intensity revealed a decreased level of N-cadherin. ***P < 0.001.

The pivotal role of radial glial cells in the neural system's development cannot be underestimated. These cells act as guiding structures, facilitating the migration of neurons during the complex process of neural tissue formation [12]. The structural integrity of the radial glial scaffold is crucial to ensure proper neuronal migration, providing a stable and organized framework for navigation [13]. Nestin, an intermediate filament protein, exhibits a high abundance in radial glial cells during early embryonic development and plays a crucial role in the organization and maintenance of radial glial scaffolds [14]. The impact of Lgl1 deletion on radial glia was investigated using antibodies against Nestin. The results demonstrated that in the control group, apical and basal processes of radial glia extended cohesively throughout the entire tectum region (Fig. 4F). This organized extension guarantees accurate migration and positioning of tectum neurons, which are vital for optimal nervous system functioning. In LP-cko mice, disturbances were observed in Nestin expression, leading to alterations in scaffold structure and organization (Fig. 4F’). Consequently, this could have profound implications on migratory patterns and positioning of tectum neurons, potentially affecting overall midbrain development and function.

N-cadherin is a key component of adhesion and can mediate the interaction between neurons and radial glial cells during migration [15]. The neuroepithelium in tectum maintain the integrity of cell polarity and adhesion connections. In the control mice, N-cadherin was concentrated in the apical portion of VZ at E13.5 (Fig. 4H). However, a subset of the neuroepithelium randomly exhibits a loss of adhesion connections in the LP cko mice tectum (white arrows in Fig. 4H’). Loss of Lgl1 disrupts adhesive connections, leading to aberrant glial cell arrangement, subsequent abnormal neuronal migration, and ultimately resulting in atypical midbrain tectum development.

4. Discussion

In this study, we get Lgl1 conditional knockout mice in midbrain by mating mice with Lgl1(Flox/Flox) and Pax2-Cre mice, reported that the mutation in mice results in malformation in midbrain development. Histological results showed that there was no difference in the size of midbrain between LP cko and WT mice at E12.5. However, the neuroepithelial cells of midbrain were disordered, which should be due to the loss of the polarity of the neuroepithelial cells in the ventricle region due to Lgl1 deletion. In E16.5 mice, there were significant expanded aqueduct. We proposed that loosely arranged neuroepithelial cells in the midbrain have the potential to undergo shedding, leading to aqueduct blockage. Consequently, as cerebrospinal fluid accumulates, an increase in pressure occurs, resulting in expansion of the aqueduct. In addition, there was abnormalities in the tectum, with a longer head-to-tail distance, but a significant thinning of the cortex, which persisted into adult LP cko mice.

To elucidate the etiology of tectum dysplasia, we employed PH3 antibody labeling to visualize proliferating cells within the tectum of LP cko mice. The results demonstrated a significant escalation in the number of proliferating cells in the tectum of LP cko mice, with increased CyclinD labeled cells within the cell cycle, further corroborating that Lgl1 deletion results in abnormal proliferation of nerve cells in the midbrain of LP CKO mice. The detection of apoptosis in embryonic tectum was also conducted using the TUNEL assay, which revealed a significantly higher number of apoptotic cells in the tectum of LP cko mice compared to WT mice, with the majority of these cells being neural stem cells. The impact of apoptosis on the neuron count at the neural stem cell level is not characterized by a mere reduction. Consequently, even in the presence of excessive neural stem cell proliferation, a regulatory mechanism involving apoptosis is in place to preserve the normal development of the tectum. However, the effects of LGL1 loss on midbrain development are irreversible, and the increased apoptosis of neural stem cells may contribute to the reduction of neurons in the tectum, characterized by thinning of the cortex.

In the course of neuronal migration, neuronal precursor cells undergo forward progression, alter their direction, or switch migration modes to accomplish their final destination, which serves as the foundation for nervous system functionality [16,17]. In this study, we employed BrdU labeling tests to identify migration disorders in LP cko mice, a finding tightly associated with the dysplasia of the tectum. It has been reported that neurons generated by the division of cortical ventricles migrate to the final target position of the cortical plate along the glial fibers of radial glia cells. The maintenance of the morphology of radial glia cells, which provide the migration scaffold for neurons, is crucial for the formation of the layer of skin structure [12,18]. In this study, Nestin was used to label the embryonic glial cells, revealing that the radial arrangement of glial cells in the cortical region was significantly disrupted, which suggesting that Lgll was important for the morphological maintenance of radial glial cells. Neurons might migrate along the disordered radial glial cells and might fail to reach the correct target position, resulting in abnormal cortical development, narrowing of radial distance and lengthening of cephalocaudal direction distance.

The radial glial cells are interconnected through adhesion junctions and other complexes in close proximity to the ventricular region [19]. Loss of Lgl1 leads to gradual deterioration of adhesion junctions, causing retraction of radial glial cells towards the fibroid process near the ventricular region and disrupting their orderly and regular radial arrangement pattern. The disturbance in radial arrangement of radial glial fibers is associated with breakdown of adhesion connections. N-cadherin regulates migration of cortical locomoting neurons dependent on radial glial fibers. In our research, the expression pattern of N-cadherin was impaired in LP cko mice, resulting in an irregular arrangement of glial cell fibers, thereby disrupting neuronal migration and ultimately leading to the tectum dysplasia.

Funding

This work is supported by The Construction Engineering Special Fund of ‘Taishan Scholars’ of Shandong Province (tsqn202211135), National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (81801126), Shandong Province Natural Sciences Foundation (ZR2015PC020).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Congzhe Hou: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Aizhen Zhang: Methodology, Formal analysis. Tingting Zhang: Data curation. Chao Ye: Software. Zhenhua Liu: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Jiangang Gao: Writing – review & editing, Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Zhenhua Liu, Email: 60030127@sdutcm.edu.cn.

Jiangang Gao, Email: jggao@sdfmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sokpor G., Brand-Saberi B., Nguyen H.P., Tuoc T. Regulation of cell delamination during cortical neurodevelopment and implication for brain disorders. Front Neurosci-Switz. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.824802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts B. Neuronal migration disorders. Radiol. Technol. 2018;89:279–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirier K., Saillour Y., Bahi-Buisson N., Jaglin X.H., Fallet-Bianco C., Nabbout R., Castelnau-Ptakhine L., Roubertie A., Attie-Bitach T., Desguerre I., Genevieve D., Barnerias C., Keren B., Lebrun N., Boddaert N., Encha-Razavi F., Chelly J. Mutations in the neuronal ss-tubulin subunit TUBB3 result in malformation of cortical development and neuronal migration defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4462–4473. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beal J.C. Case report: neuronal migration disorder associated with chromosome 15q13.3 duplication in a boy with autism and seizures. J. Child Neurol. 2014;29:Np186–Np188. doi: 10.1177/0883073813510356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valiente M., Marin O. Neuronal migration mechanisms in development and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jossin Y. Molecular mechanisms of cell polarity in a range of model systems and in migrating neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2020;106 doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2020.103503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govek E.E., Hatten M.E., Van Aelst L. The role of Rho GTPase proteins in CNS neuronal migration. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:528–553. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson S.A., Marin O., Horn C., Jennings K., Rubenstein J.L. Distinct cortical migrations from the medial and lateral ganglionic eminences. Development. 2001;128:353–363. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baek K.H. The first oncogene in Drosophila melanogaster. Mutat. Res. 1999;436:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(98)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humbert P., Russell S., Richardson H. Dlg, Scribble and Lgl in cell polarity, cell proliferation and cancer. Bioessays. 2003;25:542–553. doi: 10.1002/bies.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Justice N.J., Jan Y.N. A lethal giant kinase in cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:273–274. doi: 10.1038/ncb0403-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen N.J., Lyons D.A. Glia as architects of central nervous system formation and function. Science. 2018;362:181. doi: 10.1126/science.aat0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu X., Duan M., Song L., Zhang W., Hu X., Zhao S., Chen S. Morphological changes of radial glial cells during mouse embryonic development. Brain Res. 2015;1599:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lendahl U., Zimmerman L.B., McKay R.D. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawauchi T., Sekine K., Shikanai M., Chihama K., Tomita K., Kubo K., Nakajima K., Nabeshima Y., Hoshino M. Endocytic pathways regulate cortical neuronal migration through N-cadherin trafficking. Neurosci. Res. 2010;68:E91. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.07.166. E91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franco S.J., Muller U. Extracellular matrix functions during neuronal migration and lamination in the mammalian central nervous system. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:889–900. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee A.R., Ko K.W., Lee H., Yoon Y.S., Song M.R., Park C.S. Putative cell adhesion membrane protein Vstm5 regulates neuronal morphology and migration in the central nervous system. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:10181–10197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0541-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto H., Mandai K., Konno D., Maruo T., Matsuzaki F., Takai Y. Impairment of radial glial scaffold-dependent neuronal migration and formation of double cortex by genetic ablation of. Brain Res. 2015;1620:139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song X.Q., Zhu C.H., Doan C., Xie T. Germline, stem cells anchored by adherens junctions in the ovary niches. Science. 2002;296:1855–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.1069871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]