Abstract

While idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common type of fibrotic lung disease, there are numerous other causes of pulmonary fibrosis that are often characterized by lung injury and inflammation. Although often gradually progressive and responsive to immune modulation, some cases may progress rapidly with reduced survival rates (similar to IPF) and with imaging features that overlap with IPF, including usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)–pattern disease characterized by peripheral and basilar predominant reticulation, honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis. Recently, the term progressive pulmonary fibrosis has been used to describe non-IPF lung disease that over the course of a year demonstrates clinical, physiologic, and/or radiologic progression and may be treated with antifibrotic therapy. As such, appropriate categorization of the patient with fibrosis has implications for therapy and prognosis and may be facilitated by considering the following categories: (a) radiologic UIP pattern and IPF diagnosis, (b) radiologic UIP pattern and non-IPF diagnosis, and (c) radiologic non-UIP pattern and non-IPF diagnosis. By noting increasing fibrosis, the radiologist contributes to the selection of patients in which therapy with antifibrotics can improve survival. As the radiologist may be first to identify developing fibrosis and overall progression, this article reviews imaging features of pulmonary fibrosis and their significance in non-IPF–pattern fibrosis, progressive pulmonary fibrosis, and implications for therapy.

Keywords: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis, Thin-Section CT, Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

© RSNA, 2024

Keywords: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis, Thin-Section CT, Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

Summary

CT interpretation is key to the appropriate categorization of pulmonary fibrosis, which impacts diagnosis, prognosis, and management of patients that may potentially benefit from antifibrotic agents.

Essentials

■ In addition to identifying CT characteristics of a given fibrotic lung disease, the radiologist must assess follow-up studies for increasing extent or degree of fibrosis or a change in the pattern of fibrosis.

■ Since honeycombing is associated with a worse clinical outcome in both idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnoses, its presence is considered an indication for antifibrotic therapy regardless of the underlying disease if standard therapy has failed.

■ Patients with nearly any cause of a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern at CT, including connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and familial interstitial pneumonia, have substantially more rapid progression and worse survival rates.

■ By noting increasing fibrosis, the radiologist contributes to the selection of patients in which therapy with antifibrotics can improve survival.

Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis may develop in various disease states characterized by chronic inflammation and/or lung injury, while in other instances, the underlying causes remain unknown (1,2). Given recently released guidelines with expanded recommendations for antifibrotic therapy in different causes of pulmonary fibrosis, accurate categorization of fibrosis is increasingly important (3). However, evolving terminology and diagnostic criteria can be challenging, with subsequent implications for therapy and prognosis.

The advent of thin-section CT dramatically advanced imaging of interstitial lung disease and the morphologic changes resulting from pulmonary fibrosis. Over 3 decades of combined radiologic, pathologic, and pulmonary research has explored radiologic-pathologic correlations of thin-section CT features and their clinical significance, leading to the formulation of international clinical practice guidelines for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and, most recently, progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) (1,2). Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), long established as the most common of the idiopathic pneumonias, is now recognized as a common radiologic and pathologic pattern of end-stage pulmonary fibrosis occurring due to various causes. However, most commonly, the etiology remains unknown, and IPF may be diagnosed at multidisciplinary discussion (MDD). A combination of peripheral and basal predominant reticulation, honeycombing (HC), traction bronchiectasis (TBr), and traction bronchiolectasis (Tbr) are key components of the UIP pattern of fibrosis at thin-section CT as defined by the American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the treatment of IPF (1). When all of these thin-section CT features are present, imaging is said to be consistent with radiologic UIP and predictive of histologic UIP with a high confidence level (1). Even when not part of the UIP pattern of disease, HC, TBr, and Tbr are signs of histologic fibrosis. There are other thin-section CT features that represent fibrosis, though less consistently. Reticulation correlates with microscopic HC in UIP-pattern fibrosis but also occurs in various nonfibrotic processes (3). Similarly, ground-glass opacity may correlate with microscopic intralobular fibrosis, especially if interspersed with TBr and Tbr. However, in many instances, ground-glass opacity indicates inflammatory, possibly reversible disease, including acute exacerbation of IPF (4,5). For a detailed discussion of imaging findings in pulmonary fibrosis, please refer to the review article by Hobbs and colleagues (6). These same thin-section CT features may occur in known causes of fibrosis, including hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), and granulomatous inflammation, where a specific pattern of fibrosis is not recognized but the presence of HC, TBr, and Tbr is associated with a poorer prognosis (5,7). In these cases, variant distributions of fibrosis or associated nonfibrotic CT features may suggest a known disease as the cause of fibrosis. Identifying worsening non-UIP–pattern fibrosis is important as these patients may have an underlying disease that is treatable by immune modulation. However, if the fibrosis is progressive despite standard therapy, new guidelines include treatment with antifibrotic agents (2).

IPF is the most frequent specific diagnosis in fibrogenic lung disease, most commonly correlating to the histologic and thin-section CT patterns of UIP (1). However, both the histologic and radiologic patterns of UIP are not diagnostic of IPF and can occur due to various secondary causes (7,8). Additionally, the histologic and radiologic UIP patterns are not synonymous, but when a specific combination of thin-section CT findings is present, the predictive value of the radiologic UIP pattern for histologic UIP is high (1). As such, thin-section CT evidence of UIP negates the need for pathologic evaluation if clinical workup and MDD do not identify a known cause of pulmonary fibrosis (1). The radiologist should utilize the term UIP to refer to specific thin-section CT patterns of interstitial fibrosis as defined by the 2018 guidelines for diagnosis of IPF (1,6). The term IPF is reserved for cases in which this diagnosis has been determined at MDD (1). Antifibrotic therapy with pirfenidone or nintedanib is an established recommendation for patients with an IPF diagnosis, in which untreated disease has a 5-year survival rate of 31% (9).

Many cases of pulmonary fibrosis will not meet the diagnostic criteria of IPF at MDD and occur in clinically heterogeneous settings with imaging findings that often are indeterminate or not consistent with the UIP pattern. The most common causes of pulmonary fibrosis other than IPF include connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD), HP, sarcoidosis, occupational lung disease, and familial interstitial pneumonia (FIP) (8). In these cases of non-IPF, variant distributions of the fibrosis or additional thin-section CT findings including ground-glass opacity, consolidation, air trapping, cysts, nodules, and pleural disease may be supportive of a known cause of pulmonary fibrosis, but confirmation of diagnosis requires clinical features ideally in conjunction with pathology (1,2). In the absence of diagnostic serologic tests or a documented antigen, lung biopsy should be considered as the presence of microscopic HC or inflammatory features may impact treatment decisions regardless of the imaging pattern (10). Inflammation is a key component of the underlying pathophysiology in some of these diseases, which is commonly treated with anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory agents to prevent or delay the development of pulmonary fibrosis (10).

In a substantial subset of patients with non-IPF, clinical, physiologic, and/or radiologic progression may occur despite appropriate medical management of diseases and are usually associated with a better prognosis than IPF (2,8). In these patients, the development of a UIP pattern or other signs of worsening fibrosis at CT are associated with a clinical picture that closely mimics the course of IPF, including reduced survival rates (2,8). Documented fibrosis progression within a 12-month interval is now termed PPF and is recognized as an indication for antifibrotic therapy, even in cases traditionally managed by immune modulation (2). Recent guidelines on PPF recommend the use of nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that interferes with fibroblast activation and functions as an antifibrotic agent in cases of non-IPF that have failed standard management (2).

Given an expanding spectrum of patients with pulmonary fibrosis in whom antifibrotic therapy may be beneficial, it is clinically helpful to categorize patients into the three following groups which are in part determined by thin-section CT features of UIP and IPF according to the Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline for the treatment of IPF: (a) radiologic UIP pattern and IPF diagnosis, (b) radiologic UIP pattern and non-IPF diagnosis, and (c) radiologic non-UIP pattern and non-IPF diagnosis. Importantly, worsening fibrosis with imaging findings of non-IPF disease may lead to recognition of PPF with a direct effect on management (Fig 1). As such, in addition to identifying CT characteristics of a given fibrotic lung disease, the radiologist must assess follow-up studies for increasing extent or degree of fibrosis or a change in the pattern of fibrosis. In this review article, we address the clinical significance of various CT characteristics of pulmonary fibrosis in non-IPF–pattern fibrosis and PPF and the implications for therapy.

Figure 1:

Diagram shows decision tree for pulmonary fibrosis with pattern and therapy considerations.

Radiologic UIP Pattern and IPF Diagnosis

General Overview and Considerations

An aggregate of defined imaging findings at thin-section CT, recognized as the radiologic UIP pattern, is strongly associated with histologic UIP (1,6). Individual thin-section CT characteristics of the UIP pattern, including HC, TBr, and Tbr, have implications for diagnosis and outcome in IPF and non-IPF diseases.

Thin-Section CT Patterns

The 2018 Clinical Practice Guideline for the treatment of IPF specifies four thin-section CT patterns encountered in the workup of IPF in decreasing order of likelihood of a UIP or IPF diagnosis: (a) UIP, (b) probable UIP, (c) indeterminate for UIP, or (d) alternative diagnosis to IPF (1). Radiologic HC, identified by clustered cystic airspaces with similar diameters of 3–10 mm that are usually subpleural in location and associated with thick walls, is a key component of the UIP pattern. When present, HC has a positive predictive value of 90%–100% for histologic UIP (1,11). However, radiologist level of agreement for the diagnosis of HC is only moderate as in some cases it may be difficult to differentiate HC from TBr and Tbr, paraseptal emphysema, cystic lung disease, or airspace enlargement with fibrosis (12) (Fig 2).

Figure 2:

Radiologic indeterminate for usual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and unclassifiable fibrosis diagnosis in a 55-year-old male patient with a 30-pack-year smoking history and negative serologic findings and exposure history. (A) Axial thin-section CT image through the upper lobes shows subpleural cystic spaces in the right and left upper lobes (arrows) that are linearly arranged and multiple layers deep, demonstrating overlap with the imaging features of honeycombing (HC). (B) Axial thin-section CT image through the mid lungs shows mild ground-glass opacity and peripheral reticulation (open circles) without additional features of a specific diagnosis. (C) Photomicrograph from surgical right lung biopsy demonstrates interstitial pneumonia with lymphoid aggregates (long arrow) and pleuritis (short arrow), supporting an inflammatory cause of fibrosis including connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (hematoxylin-eosin stain; low-power magnification). Airspace enlargement (open circle) was present without remodeling or HC and explains the presence of the above noted cystic spaces that can mimic HC at thin-section CT.

Identification of radiologic HC is important due to its clinical significance, as the presence and extent of radiologic HC along with other signs of fibrosis, including reticulation and TBr, predict mortality in patients with IPF (10). A greater extent of fibrosis at quantitative assessment of baseline CT has also been associated with poorer transplant-free survival rates in IPF independent of pulmonary function (13).

Although HC, TBr, and Tbr constitute UIP-pattern fibrosis, it is important that imaging in IPF documents an absence of findings associated with non-IPF disease, including ground-glass opacity, consolidation, nodules, air-trapping, cyst formation, and pleural disease (1). Ground-glass opacity, especially if interspersed with Tbr, has been correlated with microscopic intralobular fibrosis, but it is absent or minimal in IPF and usually limited to those areas in which radiologic signs of fibrosis are evident (1,4). When abundant in the setting of fibrosis, and especially if identified in nonfibrotic regions, ground-glass opacity may be due to acute parenchymal disease, including acute exacerbation of IPF. Alternatively, it may indicate a different cause of fibrosis, especially NSIP, as is subsequently discussed (5). When reported as a new finding, ground-glass opacity will usually prompt workup to exclude an acute treatable process.

Pathology Findings and Genetics

Lower zonal volume loss due to alveolar and secondary pulmonary lobular collapse is a key histologic finding of UIP in IPF leading to the surrounding airways being pulled open, termed TBr and Tbr (3,14). Remodeling may lead to the development of bronchiolar epithelium-lined cysts, called HC cysts, arising from the distal bronchioles (15) (Fig 3). At micro-CT–pathologic correlation, reticulation represents distal lobular fibrosis with microscopic HC that is not visible on CT images (3). As such, even when HC is absent at CT, UIP may be identified histologically.

Figure 3:

Radiologic probable usual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 68-year-old male patient with confirmation of histologic usual interstitial pneumonia in lung explant. (A, B) Axial thin-section CT images through the mid and lower lung zones show peripheral reticulation with mild ground-glass opacity (open circle in A), traction bronchiectasis (closed arrows in A), and traction bronchiolectasis (open arrow in A) without honeycombing. (C) Photomicrograph of the lung explant demonstrates microscopic honeycombing. Cystic airspaces containing mucus (open circles) are separated by fibrotic septae (arrows) (hematoxylin-eosin stain; magnification ×2.5). (D) Photomicrograph through one of many fibroblastic foci (arrow) present in the explant (hematoxylin-eosin stain; magnification ×10). (Image courtesy of Christopher Sande, MD.)

Fibroblastic foci are another hallmark of pathologic UIP, representing subepithelial aggregates of active collagen-producing myofibroblasts (16) (Fig 3). When combined with subpleural and/or paraseptal, patchy, and temporally heterogeneous fibrosis with architectural distortion, the presence of fibroblastic foci and HC helps the pathologist make a diagnosis of UIP (14,16). The profusion of fibroblastic foci is an important indicator of disease activity and overall prognosis, correlating with UIP and TBr at thin-section CT (17).

Overexpression of MUC5B, which encodes for specific mucins produced by terminal bronchiolar epithelium, represents the most common and greatest overall risk factor for spontaneous IPF, increasing the risk of disease development by 6–8 times (18). It is possible that a specific genomic variant may influence the pattern of fibrosis at CT, with one study demonstrating variable frequency of the UIP pattern among patients with IPF and different MUC5B alleles (19).

Impact on Treatment and Prognosis

As IPF is the single most common diagnosis made in pulmonary fibrosis, and CT imaging findings are central to establishing its diagnosis, the radiologist contributes substantially to clinical management by identifying patients with radiologic UIP that are spared surgery for diagnosis. Open lung biopsy in this population is associated with greater morbidity and mortality due to an increased risk of air leak, failure to wean from ventilatory support, and acute lung injury (5).

In the absence of lung transplantation, IPF leads to progressive irreversible respiratory failure in most patients. Treatment options for IPF are limited. Corticosteroid therapy in the absence of an acute exacerbation is not effective for IPF, with some treated patients demonstrating poorer clinical outcomes than untreated cohorts (20). Reduced rates of clinical deterioration and improved survival have been documented in patients with IPF treated with pirfenidone and nintedanib, which are now considered the mainstay of therapy (1).

PPF Overview and Diagnosis

Excluding IPF, which by definition is irreversibly progressive, as many as 20%–30% of patients with various causes of fibrotic lung not characterized as IPF will develop a fibrogenic phenotype associated with rapid clinical decline and progressive fibrosis at imaging, now termed PPF (2,8). These patients have clinical outcomes that are similar to IPF rather than the underlying potentially reversible disease (2,8). Recently released guidelines define PPF by two of three criteria in patients with fibrogenic disease that is not IPF: (a) worsening symptoms, (b) progressive loss of lung function (>5% decline in forced vital capacity, greater than 10% decline in diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide), or (c) radiologic worsening with otherwise unexplained disease progression over 12 months (2). Currently, an absolute decline in forced vital capacity greater than 10% is the strongest predictor of reduced transplant-free survival, associated with at least a doubling of mortality, and it has been suggested that this value alone may be diagnostic of PPF (21). However, the rate of forced vital capacity decline is variable, subject to a lag period before becoming abnormal, and may remain relatively unchanged despite progression of clinical symptoms. In cases with marginal forced vital capacity decline, worsening of thin-section CT features was predictive of mortality, with TBr being the best predictor of mortality (22). With acute worsening of clinical symptoms or physiologic parameters, thin-section CT can be helpful by differentiating between acute disease manifesting as new ground-glass opacity or consolidation and actual progression of the fibrosis (4).

Visual recognition of worsening fibrosis, which is subject to inter- and intraobserver variability, is detected by an increase in the extent of involved parenchyma; an increase in the severity of specific CT features, such as new reticular opacities and HC; or a change in overall pattern. For instance, some patients with CTD-ILD and an initial NSIP pattern of fibrosis may develop radiologic UIP-pattern disease over time (23) (Fig 4). Imaging features indicating disease progression are listed in Table 1 (2).

Figure 4:

Radiologic nonusual interstitial pneumonia pattern–fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 50-year-old male patient with scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis established by clinical and physiologic parameters was accompanied by a change in the pattern of interstitial lung disease. (A, B) Axial thin-section (A) and sagittal (B) CT images through the lower lobes show diffuse ground-glass opacity and mild reticulation with subpleural sparing (open circle in A). Esophageal dilatation (arrow in A) is present. Imaging features are consistent with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia which was confirmed at surgical biopsy. Note suture line in the lingula (open arrow in B). (C, D) Axial thin-section (C) and sagittal (D) CT images at the same levels obtained 2 years later show a change in the radiologic pattern of fibrosis which is now consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. There is diffuse honeycombing and traction bronchiectasis. The patient underwent lung transplantation 4 months later. Pathologic evaluation of the explant confirmed usual interstitial pneumonia.

Table 1:

CT Characteristics of Developing Pulmonary Fibrosis

While the presence of HC at imaging is considered a strong predictor of progressive fibrosis and mortality, once present, it is more difficult to recognize sequential progression because of associated volume loss and architectural distortion. Quantitative lung imaging techniques, including threshold-based measures and textural analysis, may contribute to a more sensitive and reproducible assessment of lung disease, facilitating longitudinal management and evaluation of the efficacy of various treatment protocols in pulmonary fibrosis (24,25). Higher-order texture-based analysis can be used to detect the presence, sequential changes in distribution and volume, and relative proportion of low-attenuation lesions (air trapping, HC) and fibrotic reticular opacities, from which quantitative lung fibrosis scores of specific CT features can be derived (Fig 5). Changes in quantitative CT scores have been correlated with changes in pulmonary function tests and overall survival with CTD-ILD. It is likely that once established, these methods will assist in the detection and monitoring of progressive fibrosis, but further work is required for validation (24,25).

Figure 5:

Texture-based CT quantification demonstrates progressive disease in a 68-year-old male patient with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. (A) Coronal CT image with texture analysis overlay reveals a data-driven texture analysis score of 26%. (B) Coronal CT image with texture analysis overlay at 3-year follow-up demonstrates progression, with a data-driven texture analysis score of 39%. (Image courtesy of David Lynch, MD, and Stephen M. Humphries, PhD, Quantitative Imaging Laboratory, National Jewish Health.)

There are numerous causes of pulmonary fibrosis with various imaging patterns that can progress and hence be classified as PPF. Certain patients with CTD-ILD, HP, and FIP will have a UIP pattern at thin-section CT. These patients will be discussed below under the Radiologic UIP Pattern and Non-IPF Diagnosis section. Further, some patients with the same entities of CTD-ILD, HP, and FIP may develop PPF but have imaging findings that would be inconsistent with a UIP pattern. These patients, as well as pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) and sarcoidosis, will be discussed in the Radiologic Non-UIP Pattern and Non-IPF Diagnosis section. It is important to distinguish between these two categories, even with the same underlying lung disease, due to differences in management and prognosis. Furthermore, it is possible that genomic and other factors contribute to the likelihood of a patient developing PPF in the setting of an underlying lung disease, and these factors are also discussed below.

Radiologic UIP Pattern and Non-IPF Diagnosis

General Overview and Considerations

The radiologic and histologic patterns of UIP with HC can be identified in patients who have a cause of pulmonary fibrosis that is not IPF, including CTD-ILD, HP, and FIP (23,26,27). While MDD is required to differentiate secondary from idiopathic causes of UIP, the clinical workup can be noncontributory, especially in HP, where the antigen remains unknown in 60% of patients (28). Guidelines recommend that HP should be reasonably excluded in any new ILD, including the UIP pattern (28).

Heterogeneous genetic defects lead to different mechanisms of lung injury that may be associated with different radiologic patterns of fibrosis, including UIP, which can occur in younger patients and potentially demonstrate rapid progression (29,30). Genomic variants are recognized in 30% of patients with FIP, defined by at least two family members with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, including one IPF diagnosis, and may be associated with clinical syndromes (31,32). These same variants may contribute to UIP-pattern disease with visible HC and increased clinical severity with HP and CTD-ILD (33,34).

Since HC is associated with poorer clinical outcomes in both IPF and non-IPF diagnoses, its presence is considered an indication for antifibrotic therapy regardless of the underlying disease if standard therapy has failed. Furthermore, developing HC at imaging may contribute to a PPF diagnosis. The relevance of the UIP pattern to determining clinical course and treatment options in patients with various underlying lung diseases has promoted recent discussion of the histologic diagnosis of UIP as a “stand-alone diagnosis” (35). The authors note that in non-IPF fibrotic interstitial lung disease, including HP, histologic findings vary over time. These findings demonstrate predominant inflammatory features if biopsy is performed close to the onset of clinical symptoms but demonstrate various fibrotic features and a profibrotic molecular profile if performed years after the onset of symptoms (35).

Thin-Section CT Patterns

UIP pattern with CTD.—Rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis are the most common CTD-ILDs that lead to a radiologic and pathologic UIP pattern (23,36). For patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 24%–59% demonstrate a definite UIP pattern at CT (23,37) (Fig 6). Up to one-third of patients with systemic sclerosis–ILD have HC and UIP-pattern features at CT (36). The distribution of HC may be useful in identifying those with CTD-ILD versus IPF. Imaging findings that support UIP due to CTD-ILD include the following: (a) exuberant HC (greater than 70% cross-sectional area of the lung affected by fibrosis), which is often associated with confluence and near complete involvement of the lower lobe parenchyma; (b) straight-edge sign (sharp demarcation and abrupt transition between basilar fibrosis and normal lung, often best seen on coronal reconstructions); (c) anterior upper lobe sign (concentration of fibrosis in the anterior upper lobes); and (d) the four-corner sign (anterolateral upper and posterosuperior lower lobe involvement) (37,38) (Fig 7). Nonpulmonary findings at CT may assist in suggesting a non-IPF diagnosis in CTD-ILD with a UIP pattern (Table 2). Nonetheless, diagnosis of CTD-ILD is not always possible based on imaging alone, highlighted by the poor level of agreement between expert radiologists for CTD-ILD diagnosis (κ = 0.17) (39).

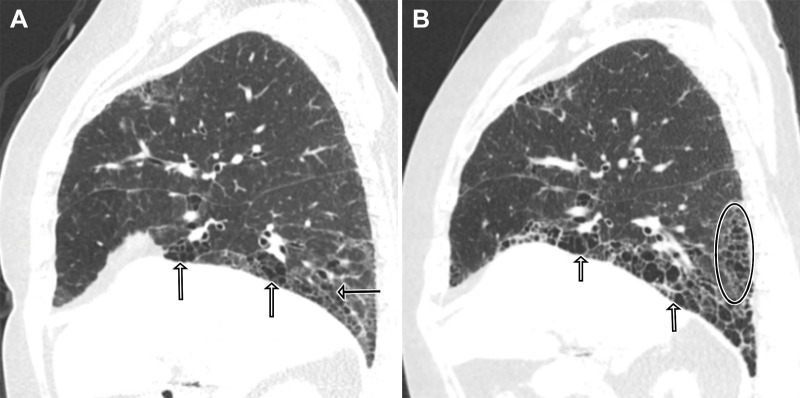

Figure 6:

Radiologic usual interstitial pneumonia pattern–fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 58-year-old female patient with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis established by clinical and physiologic parameters was accompanied by worsening fibrosis at imaging. (A) Sagittal CT image through the right lower lobe shows subpleural predominant coarse reticulation with honeycombing (open arrows), traction bronchiectasis (arrow), and intermixed areas of ground-glass opacity. More mild findings are observed in the right middle lobe and anterior segment of the right upper lobe. (B) Sagittal CT image 2.5 years later shows decreased ground-glass opacity and increasing extent of honeycombing (open circle) and size of the cysts (open arrows).

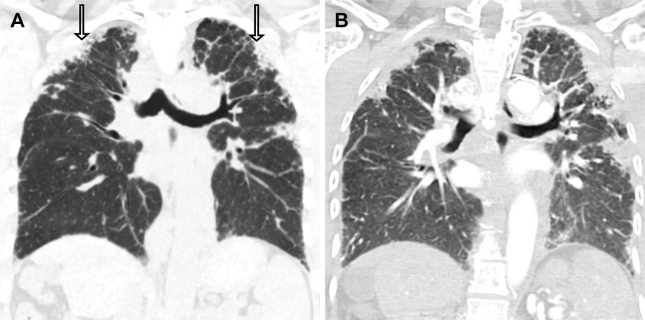

Figure 7:

Radiologic usual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 45-year-old female patient with systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. The distribution of honeycombing (HC) supports connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease. (A) Axial thin-section CT image at the level of the main pulmonary artery (*) shows HC in the anterolateral upper lobes and superior segment of the left lower lobe. (B) Axial thin-section CT image at the level of the diaphragm shows exuberant HC. The esophagus is dilated and fluid filled (arrow). (C) Coronal CT reconstruction shows exuberant HC with sharp demarcation from normal lung parenchyma (arrow). At lung transplantation, the explant revealed histologic usual interstitial pneumonia with architectural distortion due to diffuse HC with fibroblastic foci.

Table 2:

Findings in Fibrotic Lung Disease Suggesting an Alternative Diagnosis to a UIP Pattern and Their Associated Differential Diagnosis

UIP pattern with HP.— In most patients, fibrotic HP (FHP) can be differentiated from IPF by its mid or upper lobe predominance, often involving the perihilar portions of the lungs with associated mosaic attenuation and air trapping at expiratory imaging. These findings are considered typical for FHP according to the 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in Adults (28,40) (Fig 8) (Table 2). Absence of lower zonal disease favors FHP over IPF and NSIP, especially if air trapping is observed in areas without overt fibrosis (40). However, 30%–50% of patients with FHP have lower lobe–predominant disease that is potentially indistinguishable radiologically from IPF, especially since signs of inflammation, such as centrilobular nodularity, are often absent in FHP (28,40) (Fig 9). According to Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in Adults, patients with UIP, probable UIP, and indeterminate for UIP patterns (2018 UIP/IPF guideline [1]) are considered to have indeterminate CT features for FHP if occurring without additional evidence of bronchiolar obstruction (28). The three-density pattern (previously referred to as the head cheese sign) consisting of lobular air trapping, ground-glass opacity, and normal parenchyma at thin-section CT best correlates with ILD due to FHP (28,40). In HP, TBr at thin-section CT correlates with the histologic profusion of fibroblastic foci (17).

Figure 8:

Radiologic nonusual interstitial pneumonia pattern–fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 63-year-old male patient with hypersensitivity pneumonitis and a history of dust exposure. Lung biopsy demonstrated noncaseating granulomas in a perilymphatic and peribronchial distribution. (A–C) Axial thin-section CT images obtained in inspiration demonstrate widespread ground-glass opacity, mosaic lung attenuation pattern (open circles in B and C), and upper zonal peribronchial reticulation and traction bronchiectasis (arrows in B). (D–F) Axial thin-section CT images obtained in expiration accentuate geographic hyperlucent zones supporting lobular air trapping (open circles in E and F).

Figure 9:

Evolving radiologic usual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 64-year-old male patient with shortened telomeres and fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis was supported by rapidly progressive fibrosis at 9-month CT follow-up. (A) Baseline CT image at presentation. Axial thin-section CT image at the level of the aortic arch demonstrates coarse reticular opacities, confluent subpleural areas of fibrosis, traction bronchiectasis, and a few mildly hypoattenuated lobules (arrows). (B) Axial thin-section CT image at the level of the diaphragm shows mild ground-glass opacity, traction bronchiectasis, and areas of subpleural cystic change suggestive of honeycombing. (C, D) Axial thin-section CT images obtained 9 months later demonstrate worsening fibrosis in both the upper (C) and lower (D) lobes with increasing coarse reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing. Confluent bands of subpleural fibrosis in the upper and lower lobes have also increased. This case highlights the importance of thin-section CT characteristics in recognizing an underlying fibrogenic lung disease when there is radiologic usual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis.

UIP pattern with FIP and genetic variants associated with pulmonary fibrosis.— Diagnosis of FIP does not require a definitive UIP pattern at CT, with 30% of patients demonstrating atypical findings for UIP, including diffuse fibrosis in the axial plane and nonlower zonal distribution (41) (Table 2). Thin-section CT abnormalities are also identified in 22% of asymptomatic relatives of patients with FIP, with 19% demonstrating 5-year progression and 25% developing symptoms (42).

Radiologic UIP is the most common imaging pattern observed in nearly half of patients with short telomere syndrome, with another 20% having an unclassifiable pattern of fibrosis and 10% with PPFE (43). Shortened telomeres below a critical length required for DNA repair result in early onset pulmonary fibrosis, premature gray hair, aplastic anemia, cryptogenic cirrhosis, osteoporosis, and leukoplakia with an increased risk of malignancy (43).

Some patients with genetic abnormalities in surfactant secretion and production have radiologic UIP-pattern disease while others have unclassifiable fibrosis (44) (Fig 10). Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder affecting lysosomal function, leading to alternations of surfactant secretion from type II pneumocytes and variable patterns of fibrosis (Table 2). Fifty percent of all patients are of Puerto Rican descent and may clinically present with albinism and platelet dysfunction (44).

Figure 10:

Radiologic nonusual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 60-year-old male patient with Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. (A, B) Axial thin-section CT images through the upper (A) and mid (B) lung zones show axially distributed ground-glass opacity with reticulation, subpleural cysts, and honeycombing. Histologic evaluation of the explant revealed fibrosing nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Vacuolated pneumocytes characteristic of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome were present.

Pathology Findings and Genetics

Histologic UIP due to CTD is supported by the presence of lymphoid follicles and pleural thickening, but these findings are absent in many patients, thus requiring radiologic and clinical support in MDD to establish a CTD-ILD diagnosis (45).

Airway-centric distribution may support an HP diagnosis when other signs of fibrosis are present, including microscopic HC (28,40). However, granulomas, which are a hallmark of the nonfibrotic inflammatory stages of HP, are only found in a minority of cases of FHP pathologically. This may explain why there is only fair levels of agreement for the diagnosis of HP between expert pathologists and radiologists (which were 0.26 and 0.35, respectively) (39). In HP, genetic variants, including but not limited to MUC5B and shortened telomere length, have been associated with radiologic and histopathologic UIP, a greater severity of fibrosis, and reduced survival (26,28).

Recognized genetic variants in FIP most commonly involve telomere complex (15%), and abnormal encoding of MUC5B (29). These and other genetic defects are associated with a range of fibrosis patterns at pathologic examination, including UIP, NSIP, and cyst formation.

Impact on Therapy and Prognosis

Patients with nearly all causes of a UIP pattern at CT, including CTD-ILD, HP, and FIP, have substantially more rapid progression and worse survival rates (23,26,27). In FHP, individual features of HC and TBr, as well as the extent of fibrosis, are associated with increased mortality (26,28). While the mechanism is unclear, it is possible that the presence of HC itself indicates a critical degree of extracellular matrix and profibrotic milieu that is associated with disease progression and poor clinical prognosis (46).

By noting increasing fibrosis, the radiologist contributes to the selection of patients in which therapy with antifibrotics can improve survival. In patients with PPF, nintedanib is associated with a decrease in disease progression, as determined by the rate of annual decline in forced vital capacity in all radiologic patterns (2). In relatives of patients with FIP and with incidentally detected lung disease, the role of antifibrotic therapy in early disease is unknown, though these patients may benefit from surveillance.

Radiologic Non-UIP Pattern and Non-IPF Diagnosis

General Overview and Considerations

CTD-ILD; noninfectious granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis, HP, and other inhalational diseases; and PPFE are common causes of the alternative pattern for UIP and IPF. Especially in diseases with prominent granulomatous inflammation such as sarcoidosis, early and late imaging may be substantially different, and the radiologist plays an important role in recognizing early signs of fibrosis prior to the development of end-stage irreversible disease. Pulmonary fibrosis in these cases may be rapidly progressive, and even without UIP features at thin-section CT, contributes to a diagnosis of PPF.

Thin-Section CT Patterns

Non-UIP pattern with CTD.— Pulmonary fibrosis in CTD-ILD is variable in appearance and progression but most commonly manifests with CT characteristics of fibrosing NSIP, including lower lung peribronchovascular-predominant ground-glass opacity, reticulation, and TBr with associated subpleural sparing (7) (Fig 4). Patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis can present with acute (diffuse alveolar damage) and subacute (organizing pneumonia) patterns of lung injury and may have rapid progression of fibrosis. A subset of patients with CTD-ILD due to rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis can present with UIP-pattern disease, as discussed in the Radiologic UIP Pattern and Non-IPF Diagnosis section above.

Non-UIP pattern with sarcoidosis and granulomatous inflammation.— In cases of chronic inflammation with granuloma formation, diagnosis is facilitated by recognizing evolving imaging findings at serial studies. Early imaging findings include a spectrum of nodular abnormalities ranging from micronodules to masslike consolidations, ground-glass opacity, and reticulation (47) (Table 2).

Late imaging findings include peribronchial and perilymphatic fibrosis, which is often more central than peripheral, with TBr and reticulation contributing to linear patterns and bronchial distortion (48). Paracicatricial emphysema and HC may be present. Late findings of chronic granulomatous inflammation are associated with a reduction in previously identified nodular features (Fig 11). In some cases, foreign body or sarcoid granulomas are incorporated into masslike, perihilar lesions, resulting in progressive massive fibrosis (48). Additional findings supporting granulomatous disease include lymphadenopathy and extrathoracic disease (47) (Table 2).

Figure 11:

Radiologic nonusual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 49-year-old female patient with chronic granulomatous inflammation due to sarcoidosis. (A) Initial axial CT image demonstrates extensive micronodules with perilymphatic distribution. (B) Axial thin-section CT image obtained 15 years later shows central and upper zonal predominant fibrosis with volume loss, architectural distortion, coarse linear opacities, and absence of previously observed micronodules. A reduction in the degree of nodularity in association with developing fibrosis supports evolving granulomatous inflammation. In this case, slowly progressive fibrosis due to sarcoidosis was treated by immune modulation.

Non-UIP pattern with PPFE.— PPFE manifests as upper lobe volume loss and pleural thickening with subpleural reticulation and associated TBr. Unlike IPF, distribution is strikingly apical predominant (49) (Fig 12). Radiologic and pathologic features of PPFE may occur as the only manifestation of fibrotic lung disease or with other etiologies of fibrosis, including UIP and NSIP.

Figure 12:

Radiologic nonusual interstitial pneumonia–pattern fibrosis and nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis diagnosis in a 55-year-old female patient with pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) associated with a telomerase mutation. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis was established by rapidly progressive fibrosis at 12-month CT follow-up. (A) Coronal CT image through the level of the carina shows upper lobe–predominant confluent areas of subpleural fibrosis with associated pleural thickening and traction bronchiectasis (arrows). (B) Coronal CT image 12 months later shows progression of PPFE with increasing size and extent of confluent areas of fibrosis with increasing pleural retraction and volume loss. Histologic evaluation of the explant confirmed PPFE.

Pathology Findings and Genetics

In fibrotic NSIP, architectural distortion and fibroblastic foci are associated with other histologic features of NSIP, including temporally and spatially homogeneous inflammation (45). Additional pathologic findings are associated with CTD-ILD, including pleuritis, lymphoid follicles, and organizing pneumonia, which is especially common in the inflammatory myopathies (45) (Fig 2). In some patients with antisynthetase syndrome characterized by anti-Jo1 tRNA synthetase autoantibodies, severe acute lung injury with pathologic diffuse alveolar damage can lead to rapidly progressive fibrosis (50). Similarly, patients with dermatomyositis and positive antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) antibodies are at risk for developing rapidly progressive fibrosis with high mortality rates (51).

Granuloma formation in fibrogenic granulomatous ILD is associated with activation of cell-mediated immunity in response to prolonged exposure to antigens or foreign bodies, most commonly occurring in sarcoidosis, HP, and inhalational foreign body exposure (silicosis, talcosis, and berylliosis). Chronic inflammation in active granulomatous disease is fibrogenic, with developing fibrosis directed at the margins of granulomas, resulting in destruction of pre-existing granulomatous architecture and a loss of nodular features (52).

PPFE represents a combination of fibrosis and thickening of the apical visceral pleura, with adjacent alveolar wall elastosis and dense fibrosis. Acute inflammatory components are usually not identified at histologic analysis. Progressive disease in PPFE is associated with short telomere lengths or patients with coexistent UIP or HP (49).

Impact on Therapy and Prognosis

Prominent ground-glass features, consolidation, and centrilobular nodularity are associated with active inflammation which in turn supports a positive treatment response to anti-inflammatory immune-modulatory agents (53). Recognizing early granulomatous ILD is relevant because early diagnosis can substantially positively impact patient prognosis, whereas delayed diagnosis may prevent initiation of therapy prior to the onset of irreversible fibrosis (47). With progressive non-UIP–pattern fibrosis, the role of antifibrotic therapy is determined on a case-by-case basis. Some of these patients are also treated with concurrent immune modulation, especially in CTD-ILD (10,51).

Conclusion

It is important for the radiologist to identify radiologic UIP and non-UIP patterns of fibrosis; suggest alternative diagnoses for IPF in chronic inflammatory, hereditary, and granulomatous disease; and note radiologic evidence of PPF as these factors impact prognosis and therapy in fibrogenic lung disease. PPF may be viewed as a unifying concept for progressive non-IPF disease and introduces many opportunities for further investigation into the importance and quantification of CT findings in interstitial fibrosis.

Authors declared no funding for this work.

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: R.M.S. No relevant relationships. A.M.K. No relevant relationships. S.K. Deputy editor for Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging.

Abbreviations:

- CTD-ILD

- connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease

- FHP

- fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- FIP

- familial interstitial pneumonia

- HC

- honeycombing

- HP

- hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- IPF

- idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- MDD

- multidisciplinary discussion

- NSIP

- nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- PPF

- progressive pulmonary fibrosis

- PPFE

- pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis

- TBr

- traction bronchiectasis

- Tbr

- traction bronchiolectasis

- UIP

- usual interstitial pneumonia

References

- 1. Raghu G , Remy-Jardin M , Myers JL , et al. ; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society . Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018. ; 198 ( 5 ): e44 – e68 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raghu G , Remy-Jardin M , Richeldi L , et al . Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022. ; 205 ( 9 ): e18 – e47 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mai C , Verleden SE , McDonough JE , et al . Thin-Section CT Features of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Correlated with Micro-CT and Histologic Analysis . Radiology 2017. ; 283 ( 1 ): 252 – 263 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee HY , Lee KS , Jeong YJ , et al . High-resolution CT findings in fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias with little honeycombing: serial changes and prognostic implications . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012. ; 199 ( 5 ): 982 – 989 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amundson WH , Racila E , Allen T , et al . Acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease after procedures . Respir Med 2019. ; 150 : 30 – 37 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hobbs S , Chung JH , Leb J , Kaproth-Joslin K , Lynch DA . Practical Imaging Interpretation in Patients Suspected of Having Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Official Recommendations from the Radiology Working Group of the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation . Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2021. ; 3 ( 1 ): e200279 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adegunsoye A , Oldham JM , Bellam SK , et al . Computed Tomography Honeycombing Identifies a Progressive Fibrotic Phenotype with Increased Mortality across Diverse Interstitial Lung Diseases . Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019. ; 16 ( 5 ): 580 – 588 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gagliardi M , Berg DV , Heylen CE , et al . Real-life prevalence of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases . Sci Rep 2021. ; 11 ( 1 ): 23988 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khor YH , Ng Y , Barnes H , Goh NSL , McDonald CF , Holland AE . Prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis without anti-fibrotic therapy: a systematic review . Eur Respir Rev 2020. ; 29 ( 157 ): 190158 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahmed S , Handa R . Management of Connective Tissue Disease-related Interstitial Lung Disease . Curr Pulmonol Rep 2022. ; 11 ( 3 ): 86 – 98 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hansell DM , Bankier AA , MacMahon H , McLoud TC , Müller NL , Remy J . Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging . Radiology 2008. ; 246 ( 3 ): 697 – 722 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watadani T , Sakai F , Johkoh T , et al . Interobserver variability in the CT assessment of honeycombing in the lungs . Radiology 2013. ; 266 ( 3 ): 936 – 944 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lynch DA , Godwin JD , Safrin S , et al. ; Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Study Group . High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005. ; 172 ( 4 ): 488 – 493 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galvin JR , Frazier AA , Franks TJ . Collaborative radiologic and histopathologic assessment of fibrotic lung disease . Radiology 2010. ; 255 ( 3 ): 692 – 706 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seibold MA , Smith RW , Urbanek C , et al . The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis honeycomb cyst contains a mucocilary pseudostratified epithelium . PLoS One 2013. ; 8 ( 3 ): e58658 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cool CD , Groshong SD , Rai PR , Henson PM , Stewart JS , Brown KK . Fibroblast foci are not discrete sites of lung injury or repair: the fibroblast reticulum . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006. ; 174 ( 6 ): 654 – 658 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walsh SL , Wells AU , Sverzellati N , et al . Relationship between fibroblastic foci profusion and high resolution CT morphology in fibrotic lung disease . BMC Med 2015. ; 13 ( 1 ): 241 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Evans CM , Fingerlin TE , Schwarz MI , et al . Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Genetic Disease That Involves Mucociliary Dysfunction of the Peripheral Airways . Physiol Rev 2016. ; 96 ( 4 ): 1567 – 1591 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chung JH , Peljto AL , Chawla A , et al . CT Imaging Phenotypes of Pulmonary Fibrosis in the MUC5B Promoter Site Polymorphism . Chest 2016. ; 149 ( 5 ): 1215 – 1222 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raghu G , Collard HR , Egan JJ , et al. ; ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis . An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011. ; 183 ( 6 ): 788 – 824 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pugashetti JV , Adegunsoye A , Wu Z , et al . Validation of Proposed Criteria for Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023. ; 207 ( 1 ): 69 – 76 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacob J , Aksman L , Mogulkoc N , et al . Serial CT analysis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: comparison of visual features that determine patient outcome . Thorax 2020. ; 75 ( 8 ): 648 – 654 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nurmi HM , Purokivi MK , Kärkkäinen MS , Kettunen HP , Selander TA , Kaarteenaho RL . Variable course of disease of rheumatoid arthritis-associated usual interstitial pneumonia compared to other subtypes . BMC Pulm Med 2016. ; 16 ( 1 ): 107 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Humphries SM , Mackintosh JA , Jo HE , et al . Quantitative computed tomography predicts outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis . Respirology 2022. ; 27 ( 12 ): 1045 – 1053 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen A , Karwoski RA , Gierada DS , Bartholmai BJ , Koo CW . Quantitative CT Analysis of Diffuse Lung Disease . RadioGraphics 2020. ; 40 ( 1 ): 28 – 43 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kouranos V , Jacob J , Nicholson A , Renzoni E . Fibrotic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Key Issues in Diagnosis and Management . J Clin Med 2017. ; 6 ( 6 ): 62 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett D , Mazzei MA , Squitieri NC , et al . Familial pulmonary fibrosis: Clinical and radiological characteristics and progression analysis in different high resolution-CT patterns . Respir Med 2017. ; 126 : 75 – 83 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raghu G , Remy-Jardin M , Ryerson CJ , et al . Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in Adults. An Official ATS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020. ; 202 ( 3 ): e36 – e69 [Published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206(4):518.] 10.1164/rccm.202005-2032ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kropski JA , Blackwell TS , Loyd JE . The genetic basis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis . Eur Respir J 2015. ; 45 ( 6 ): 1717 – 1727 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newton CA , Batra K , Torrealba J , et al . Telomere-related lung fibrosis is diagnostically heterogeneous but uniformly progressive . Eur Respir J 2016. ; 48 ( 6 ): 1710 – 1720 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steele MP , Speer MC , Loyd JE , et al . Clinical and pathologic features of familial interstitial pneumonia . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005. ; 172 ( 9 ): 1146 – 1152 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Talbert JL , Schwartz DA , Steele MP . Familial Interstitial Pneumonia (FIP) . Clin Pulm Med 2014. ; 21 ( 3 ): 120 – 127 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ley B , Newton CA , Arnould I , et al . The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study . Lancet Respir Med 2017. ; 5 ( 8 ): 639 – 647 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Juge PA , Lee JS , Ebstein E , et al . MUC5B Promoter Variant and Rheumatoid Arthritis with Interstitial Lung Disease . N Engl J Med 2018. ; 379 ( 23 ): 2209 – 2219 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selman M , Pardo A , Wells AU . Usual interstitial pneumonia as a stand-alone diagnostic entity: the case for a paradigm shift? Lancet Respir Med 2023. ; 11 ( 2 ): 188 – 196 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winstone TA , Assayag D , Wilcox PG , et al . Predictors of mortality and progression in scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease: a systematic review . Chest 2014. ; 146 ( 2 ): 422 – 436 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chung JH , Cox CW , Montner SM , et al . CT Features of the Usual Interstitial Pneumonia Pattern: Differentiating Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease From Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018. ; 210 ( 2 ): 307 – 313 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walkoff L , White DB , Chung JH , Asante D , Cox CW . The Four Corners Sign: A Specific Imaging Feature in Differentiating Systemic Sclerosis-related Interstitial Lung Disease From Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis . J Thorac Imaging 2018. ; 33 ( 3 ): 197 – 203 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walsh SLF , Wells AU , Desai SR , et al . Multicentre evaluation of multidisciplinary team meeting agreement on diagnosis in diffuse parenchymal lung disease: a case-cohort study . Lancet Respir Med 2016. ; 4 ( 7 ): 557 – 565 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Silva CI , Müller NL , Lynch DA , et al . Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: differentiation from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia by using thin-section CT . Radiology 2008. ; 246 ( 1 ): 288 – 297 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee HY , Seo JB , Steele MP , et al . High-resolution CT scan findings in familial interstitial pneumonia do not conform to those of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia . Chest 2012. ; 142 ( 6 ): 1577 – 1583 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hunninghake GM , Quesada-Arias LD , Carmichael NE , et al . Interstitial Lung Disease in Relatives of Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis . Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020. ; 201 ( 10 ): 1240 – 1248 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mangaonkar AA , Ferrer A , Pinto E , Vairo F , et al . Clinical Correlates and Treatment Outcomes for Patients With Short Telomere Syndromes . Mayo Clin Proc 2018. ; 93 ( 7 ): 834 – 839 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Avila NA , Brantly M , Premkumar A , Huizing M , Dwyer A , Gahl WA . Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: radiography and CT of the chest compared with pulmonary function tests and genetic studies . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002. ; 179 ( 4 ): 887 – 892 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Churg A , Bilawich A . Confluent fibrosis and fibroblast foci in fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia . Histopathology 2016. ; 69 ( 1 ): 128 – 135 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Selman M , Pardo A . From pulmonary fibrosis to progressive pulmonary fibrosis: a lethal pathobiological jump . Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2021. ; 321 ( 3 ): L600 – L607 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee GM , Pope K , Meek L , Chung JH , Hobbs SB , Walker CM . Sarcoidosis: A Diagnosis of Exclusion . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020. ; 214 ( 1 ): 50 – 58 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Abehsera M , Valeyre D , Grenier P , Jaillet H , Battesti JP , Brauner MW . Sarcoidosis with pulmonary fibrosis: CT patterns and correlation with pulmonary function . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000. ; 174 ( 6 ): 1751 – 1757 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chua F , Desai SR , Nicholson AG , et al. Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis . A Review of Clinical, Radiological, and Pathological Characteristics . Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019. ; 16 ( 11 ): 1351 – 1359 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Debray MP , Borie R , Revel MP , et al . Interstitial lung disease in anti-synthetase syndrome: initial and follow-up CT findings . Eur J Radiol 2015. ; 84 ( 3 ): 516 – 523 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McPherson M , Economidou S , Liampas A , Zis P , Parperis K . Management of MDA-5 antibody positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis associated interstitial lung disease: A systematic review . Semin Arthritis Rheum 2022. ; 53 : 151959 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Patterson KC , Strek ME . Pulmonary fibrosis in sarcoidosis. Clinical features and outcomes . Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013. ; 10 ( 4 ): 362 – 370 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Elicker BM , Kallianos KG , Henry TS . The role of high-resolution computed tomography in the follow-up of diffuse lung disease: Number 2 in the Series “Radiology” Edited by Nicola Sverzellati and Sujal Desai . Eur Respir Rev 2017. ; 26 ( 144 ): 170008 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]