Abstract

Coronaviruses not only pose significant global public health threats but also cause extensive damage to livestock-based industries. Previous studies have shown that 5-benzyloxygramine (P3) targets the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) nucleocapsid (N) protein N-terminal domain (N-NTD), inducing non-native protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that impair N protein function. Moreover, P3 exhibits broad-spectrum antiviral activity against CoVs. The sequence similarity of N proteins is relatively low among CoVs, further exhibiting notable variations in the hydrophobic residue responsible for non-native PPIs in the N-NTD. Therefore, to ascertain the mechanism by which P3 demonstrates broad-spectrum anti-CoV activity, we determined the crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complex. We found that P3 was positioned in the dimeric N-NTD via hydrophobic contacts. Compared with the interfaces in MERS-CoV N-NTD, P3 had a reversed orientation in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD. The Phe residue in the MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex stabilized both P3 moieties. However, in the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complex, the Ile residue formed only one interaction with the P3 benzene ring. Moreover, the pocket in the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complex was more hydrophobic, favoring the insertion of the P3 benzene ring into the complex. Nevertheless, hydrophobic interactions remained the primary stabilizing force in both complexes. These findings suggested that despite the differences in the sequence, P3 can accommodate a hydrophobic pocket in N-NTD to mediate a non-native PPI, enabling its effectiveness against various CoVs.

Significance

5-Benzyloxygramine (P3) targets the CoV N protein N-terminal domain (N-NTD), inducing non-native protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and impairing N protein function. P3 displayed broad-spectrum antiviral activity against various CoVs. However, notable variations in the hydrophobic residue responsible for non-native PPIs exist within the N-NTD among CoVs. In this study, we identified the complex structure of the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD with the N protein inhibitor P3, revealing a reversed orientation of P3 mediating non-native PPIs compared with that of the MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex. Nonetheless, hydrophobic interactions primarily contributed to the significant formation of non-native PPIs by P3 in the hydrophobic pocket of N-NTDs, exhibiting its efficacy against diverse CoVs.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which belongs to the Coronaviridae family, is the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (1). The high mutation rate of its spike protein allows the virus to easily escape recognition by antibodies (2,3). Packaging of its viral RNA into the nucleocapsid (N) protein is a vital step during its life cycle. The N protein comprises the structured N-terminal RNA-binding (N-NTD) and C-terminal dimerization (N-CTD) domains, flanked by two intrinsically disordered regions, the N-arm and C-tail (4,5,6,7,8). The N-NTD and N-CTD are connected by a Ser/Arg-rich region called the central linker region (9). The dimeric N protein is responsible for packaging the viral genome to form a ribonucleoprotein complex, which is crucial for the assembly and maturation of the virus. Furthermore, the low mutation rate across various coronaviruses (CoVs) makes the N protein an ideal target for designing antiviral drugs (10,11,12,13,14). Manipulating protein-protein interactions (PPIs) is a key strategy in drug design (15). Some compounds can modulate PPIs by stabilizing two proteins that do not interact under normal physiological conditions or by disrupting the interface between them. This mode of action can be further divided into orthosteric and allosteric interactions (16). The formation of a protein complex can be inhibited through direct competition at the interface (orthosteric disruptor) or induction of allosteric destabilization of the PPI via molecule binding at remote sites on proteins (allosteric disruptor). Small molecules can also increase PPI stability by binding to a newly formed binding site at the interface (orthosteric stabilizer). Similar to PPI disruptors, allosteric modulation can also stabilize PPIs. Most small-molecule PPI inhibitors currently undergoing clinical trials are categorized as orthosteric disruptors, such as antagonists against the inhibitor of apoptosis family (17), mouse double minute family (18,19), and B cell lymphoma 2 family (20,21) proteins, which are important therapeutic target proteins. Additionally, non-native interactions that occur under extreme circumstances, such as those within a crystal lattice, could also be potential targets for drug development (10,11,22). This concept has been applied in various fields, including the treatment of cancer and viral infections (23), with targeting of PPIs leading to downstream effects such as altered channel opening (24), enzymatic activities (25), or oligomerization (10,11,26,27,28).

The P3 compound 5-benzyloxygramine (hereafter referred to as P3) has been established as an effective drug to manage infections caused by the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (11). This compound was demonstrated to induce an enhanced aggregation of the N protein by mediating orthosteric non-native PPIs, thus disrupting the normal function of the N protein. Most importantly, this was achieved through hydrophobic interactions, especially involving the residues surrounding W43 and F135. Moreover, P3 was also demonstrated to function as an effective antiviral agent in inhibiting mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (11). Although P3 shows broad-spectrum antiviral activity, the N-NTD and interacting sequences within the hydrophobic patch are slightly different among CoVs, with the N-NTD structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 exhibiting distinct packing arrangements. This raises the question of by which means P3 exerts a universal anti-CoV effect. To elucidate the mechanism involved in P3-mediated non-native PPIs in different CoVs, we aimed to ascertain the crystal structure of the complex of the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD and P3. Our results suggested that despite the differences in the structure and sequence between MERS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2, P3 can accommodate different conformations of N-NTD in CoVs as long as the key hydrophobic residues are preserved. In conclusion, our study may provide the mechanisms of how P3 achieves a universal anti-CoV effect.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

The compound P3 and all reagents obtained from commercial sources (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used without further purification unless otherwise mentioned.

Compound synthesis

General information

All reactions were conducted in flame-dried glassware under a nitrogen atmosphere. Dichloromethane was purified and dried from a safe purification system (SD-500) containing activated Al2O3 (AsiaWong Enterprise, Taipei, Taiwan). Flash column chromatography was carried out on silica gel 60. Thin-layer chromatography was performed on precoated glass plates of silica gel 60, with F254 detection being executed by spraying with a solution of Ce(NH4)2(NO3)6 (0.5 g), (NH4)6Mo7O24 (24.0 g), and H2SO4 (28.0 mL) in water (500.0 mL) and subsequent heating on a hotplate. Optical rotations were measured at 589 nm (Na), while 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using 400 MHz instruments from Varian (Palo Alto, CA, USA) and JEOL (Tokyo, Japan). Chemical shifts are in ppm from Me4Si, generated from the CDCl3 lock signal at δ 7.26. Infrared spectra were obtained with a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer using NaCl plates. Mass spectra were analyzed on an Orbitrap instrument with an electrospray ionization source (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

N-((5-(Benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine

N-Methylpropylamine (1.2 equivalent) was added to precooled (6°C) CH₃COOH (0.14 mL, 2.4 mmol, 2.7 equivalent), dropwise, over 30 min. After resting for 5 min, a precooled (6°C), aqueous 37% formaldehyde solution (0.08 mL, 0.94 mmol, 1.0 equivalent) was added, and the mixture was poured onto 5-(benzyloxy)indole (200 mg, 0.9 mmol, 1.0 equivalent) powder. After stirring for 24 h at 25°C, the mixture was added to a precooled (10°C) 10% NaOH solution (4.7 mL). The mixture was extracted using dichloromethane and washed with brine (aqueous saturated sodium chloride solution), and the combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The desired product was obtained by purifying via silica gel column chromatography. The obtained N-((5-(benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine (P3–8) exhibited the following characteristics: slightly yellow liquid (199 mg, 72%); Rf 0.7 (ethyl acetate/NET3 = 99/1); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.15 (s, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (dd, J = 8.3, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 3.70 (s, 2H), 2.45–2.36 (m, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H), 1.64–1.53 (m, 2H), and 0.92 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H).

Protein expression and purification

The SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD fragment (residues 41–174) and full-length SARS-CoV-2 N protein (residues 1–419) were cloned into a pET28a vector (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) fused with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag (6×His tag). The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells that were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin (CyrusBioscience, Taipei, Taiwan), overnight. The next day, cells were transferred to 800 and 1600 mL of LB medium (CyrusBioscience) and cultured until the optical density of the media reached 1.0 and 1.5 at 37°C for N-NTD and N protein, respectively. Protein expression was induced by using 1.0 and 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (CyrusBioscience) followed by incubation at 16°C and 20°C overnight for N-NTD and N protein, respectively. The bacteria were harvested through centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min; the cell pellets were suspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), NaCl (150 mM for N-NTD and 300 mM for N protein), 20 mM imidazole, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (MDBio, Taipei, Taiwan). The suspension was sonicated at 90% power (1 s pulse on and 2 s pulse off) and the supernatant clarified through centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 40 min at 4°C. His-tagged proteins (N and N-NTD) were purified using the Ni Sepharose High Performance nickel-charged IMAC resin column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and washed with a wash buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), NaCl (150 mM for N-NTD and 300 mM for N protein), and 40 mM imidazole to remove impurities. The target proteins were eluted using an elution buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), NaCl (150 mM for N-NTD and 300 mM for N protein), and 1 M imidazole; polishing was performed via size-exclusion chromatography using HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-300 and S-100 high-resolution columns (GE Healthcare) for N protein and N-NTD, respectively. The fractions were concentrated using a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 50 mM NaCl for N-NTD, or 20 mM Na3PO4 (pH 7.8) and 300 mM NaCl for N protein. The final concentration of N-NTD for crystallization was 24 mg/mL.

Crystallization and data collection

Native protein crystallization was performed using the sitting vapor diffusion method at 20°C. A 2.5 μL N-NTD protein solution was mixed with 2.5 μL of crystallization liquid containing 0.05 M Bis-Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.05 M KCl, 0.005 M spermine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich), and approximately 33%–35% polyethylene glycol 3350 (Sigma-Aldrich) equilibrated against a 400 μL solution. The N-NTD:P3 complex protein crystal was obtained by soaking the native protein with 2 mM P3 compound for 5 min at 20°C. Native N-NTD and N-NTD:P3 complex protein diffraction datasets were collected from the Taiwan Light Source beamline 07A and 05A, respectively, of the National Synchrotron Research Center (Hsinchu City, Taiwan).

Structure determination and refinement

HKL2000 software (29) was used to process and scale the collected datasets, while the Phaser package from Phenix (30) with SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD (PDB: 6m3m) as the search model (31) was used for solving the phase. The initial model was rebuilt and refined using Coot (32), while the molecular graphics were visualized using PyMol version 2.1.0 (33).

Fluorescence quenching assay

The drug-induced fluorescence quenching assay was performed by adding 1 μM N-NTD or N protein titrated with 0.25 μL, 0.5 μL, and incremental 1 μL additions of 2 mM or 1 mM P3 until saturation. For statistical significance, all measurements were performed in triplicate. The relative fluorescence intensity was determined using the following equation: (F0 − F′)/F0, where F0 is the protein fluorescence in the absence of the compound, and F′ is the fluorescence of the protein and P3 complex. The binding constant was determined by fitting the Hill equation using Prism software, version 9.4.1 (GraphPad Prism v9.0; GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Cell viability

Vero cells (cat. #CRL-1586; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were seeded in 96-well plates overnight before performing cell viability assays as previously described (11). In brief, cells were treated with different concentrations of antiviral compounds of interest for 1 h before viral inoculation. Following the removal of compounds, the virus at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 was co-incubated with cells at 37°C for an additional hour, followed by the removal of the inoculum and washing of cells twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then treated with the compounds and incubated in a humidified incubator until CellTiter-Glo (cat. #G9241; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) or MTT reagents (cat. #298-93-1; Merck, St. Louis, MO, USA) were supplemented in the culture medium. Cell viability was quantified based on colorimetric changes (MTT assay) or luminescent intensity (CellTiter-Glo) determined by a luminometer. We calculated the 50% effective concentration (EC50) and 50% cytotoxicity concentration (CC50) based on the percentage of cell viability with and without viral infections, respectively. In particular, CC50 was defined as the concentration of a candidate compound causing death to half the cell population, whereas EC50 was referred to as the concentration of a candidate compound rescuing half of the cell population (viability) from SARS-CoV-2 infection. The therapeutic index (TI) was used to evaluate the feasibility of a given compound to be applied for the treatment of a specific disease based on the ratio of CC50/EC50 (34).

Viral infection and plaque assay

For viral infection, Vero E6 cells (cat. #CRL-1586; ATCC) were cultured in complete Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (cat. #11965092; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (cat. #04-001; Biological Industries, Cromwell, CT, USA) at 37°C overnight, followed by infection with SARS-CoV-2 (cat. #NR-52281; BEI Resources, Manassas, VA, USA) at MOI of 0.1 for 1 h at 37°C. The unbound virus was removed by washing the cells thrice with PBS (cat. #10010023; Gibco). To perform the plaque assay, Vero E6 cells were also seeded in 12-well plates and incubated at 37°C overnight before the plaque assay. The SARS-CoV-2 samples were diluted serially with DMEM without FBS, and 100 μL of each diluted sample was added to a well, followed by incubation for 1 h with agitation every 15 min. After incubation, the inocula were removed and washed with PBS. An overlay medium consisting of 2× minimum essential medium (cat. #11935046; Gibco) and 1.5% (w/v) agarose (UltraPure, cat. #16520050; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 1:1 ratio was added to the wells, followed by incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 days. The plates were further fixed with 10% (v/v) formalin containing 0.2% (w/v) crystal violet, and the plaques were counted.

Results

Differences in the sequence of N-NTD and structural position of P3 between MERS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2

The P3 compound was selected through structure-based virtual screening by targeting the W43 hydrophobic pocket of the MERS-CoV N-NTD (11). The crystal structure of the MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex demonstrated highly hydrophobic residues surrounding P3 that created non-native PPIs. In the same study, P3 was also demonstrated to inhibit MHV. In this study, we aimed to verify the cytotoxicity and anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of P3 in Vero E6 cells by evaluating the CC50 and EC50 values of P3 (Fig. S1, A–C). We identified that the calculated TI value of P3 was 21.9, indicating its favorable safety and efficacy for counteracting SARS-CoV-2 infection. The TI value for the efficacy of P3 against SARS-CoV-2 resembled that of P3 against MERS-CoV (11). These results indicated that P3 has broad-spectrum antiviral activity against CoVs. However, the N protein sequences are not conserved among CoVs, exhibiting low sequence identities of 26.37%, 34.62%, 48.59%, and 48.61% for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), MHV, SARS-CoV-2, and SARS-CoV, respectively, compared to those of MERS-CoV (Fig. S2 B).

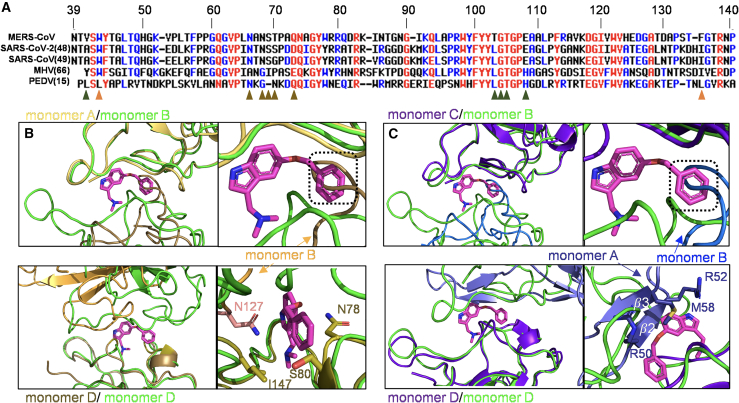

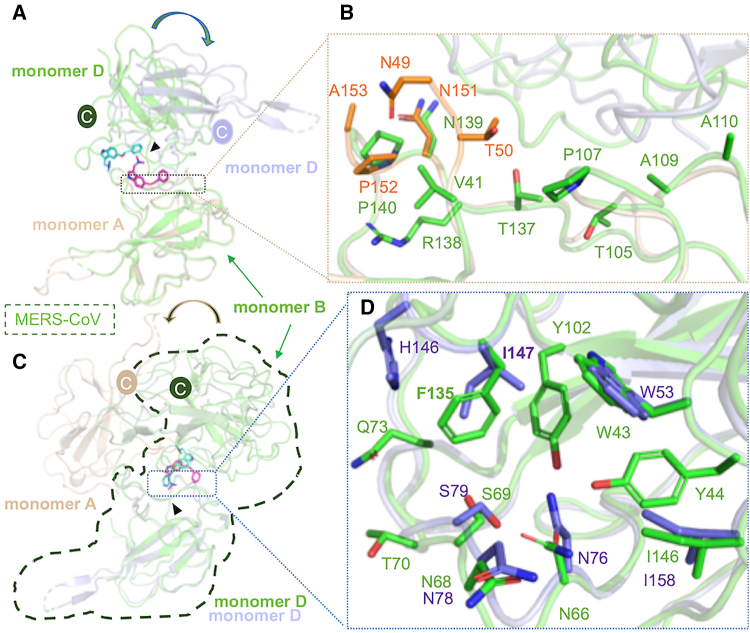

Although the N-NTDs share slightly higher sequence identities (Fig. S2 C), we have identified a critical residue substitution in this important binding region at the hydrophobic interfaces among N-NTDs in various CoVs (Fig. 1 A). The key residue Phe, responsible for mediating non-native PPIs, was substituted by Ile in SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MHV and by Leu in PEDV. Differences have also been reported regarding other residues involved in mediating hydrophobic interactions between MERS-CoV and P3, such as T103 in MERS-CoV, which is substituted with Leu in other CoVs. Furthermore, T70 in MERS-CoV is also replaced by different residues in other CoVs. Similarly, a structural comparison of two different structures, SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD and MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3, revealed that the P3 position in MERS-CoV would interfere with the alignment of P3 with SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD. When superimposing monomer A of a SARS-CoV N-NTD structure (PDB: 6m3m) with monomer B of MERS-CoV (PDB: 6KL6), we observed that a loop in monomer B of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD might interfere with the benzene ring of P3. Similarly, we observed a potential clash with P3 when superimposing monomer D from both structures (Fig. 1 B). Additionally, upon comparing monomer C of another SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD structure (PDB: 7cdz) with monomer B of MERS-CoV N-NTD, we noted the potential interference of a loop in monomer B with the benzene ring of P3. In the comparison of monomer D from both structures we observed a clash, particularly involving the β2 and β3 in monomer A of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD, notably influenced by the side chain of M58 (Fig. 1 C). These results demonstrated that despite a substitution in key residues and variations in the interface between N-NTD dimers, P3 retained its efficacy against SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the structure and sequence of the N-terminal domain (N-NTD) between SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. (A) Sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of the N protein from various CoVs. Alignment was performed using Multalin (35). The results were color-coded based on amino acid identity, with distinct colors indicating variations in polarity or charge. Orange triangles highlight hydrophobic residues that participate in the mediating of non-native PPI; dark-green and brown triangles represent the interface residues between monomers B and D on MERS-CoV and P3, respectively. (B) Superimposition of monomers A and D of SARS-CoV-2-N-NTD (PDB: 6m3m) to monomers B and D of MERS-CoV-N-NTD (PDB: 6KL6), respectively. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values for both comparisons were 0.623 (98 to 98 atoms) and 0.779 (100 to 100 atoms), respectively. (C) Superimposition of monomers C and D of SARS-CoV-2-N-NTD (PDB: 7cdz) to monomers B and D of MERS-CoV-N-NTD (PDB: 6KL6). The RMSD values for both comparisons were 0.639 (100 to 100 atoms) and 0.661 (98 to 98 atoms), respectively. The two SARS-CoV-2-N-NTD are shown in brown and purple-blue, whereas MERS-CoV-N-NTD is in green. To see this figure in color, go online.

P3 directly targeted the non-native dimer interface

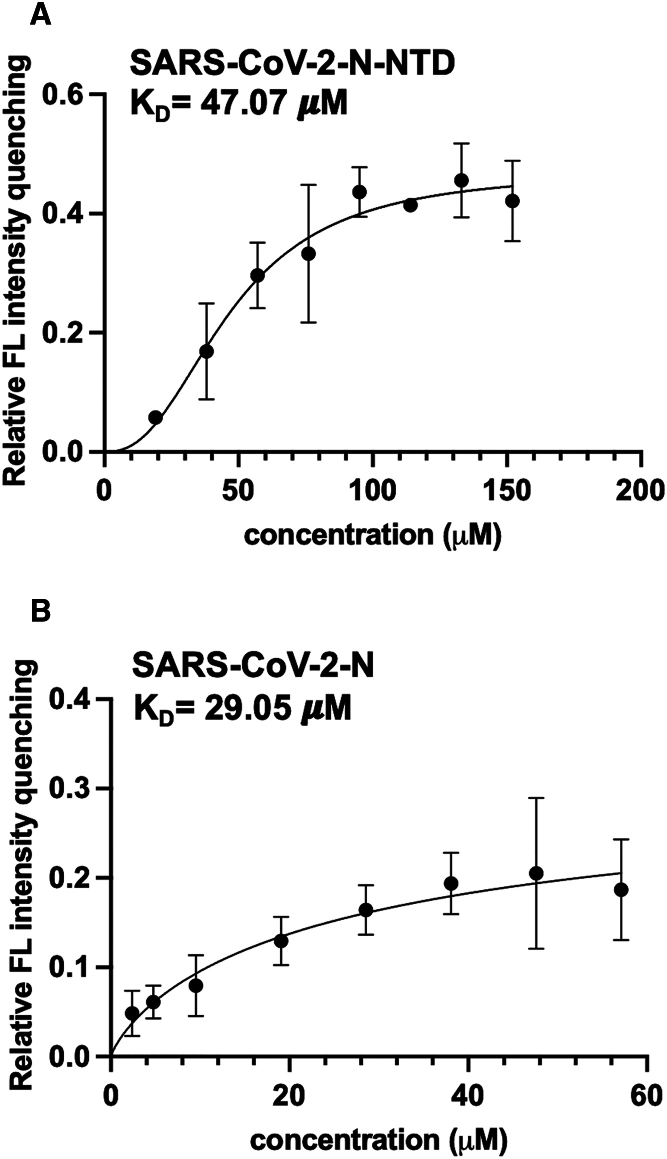

To ascertain the mechanism by which a substitution in a crucial residue or the variation of the P3 position in the hydrophobic interfaces of the N-NTD in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 do not affect the antiviral efficacy of P3 against SARS-CoV-2, we aimed to elucidate the crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complex. First, to check whether P3 targets proteins, we performed a fluorescence quenching assay. We observed a decrease in fluorescence and shift to a lower wavelength, indicating compound binding (36). Therefore, we measured the fluorescence intensity following a series titration of compounds to calculate their binding constant (KD). We found that the KD values for the SARS-CoV-2 N protein and N-NTD were 23.18 μM and 47.07 μM, respectively (Fig. 2). This finding suggested that P3 effectively stabilized and interacted with both the N protein and N-NTD of SARS-CoV-2. We next purified SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD using size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. S3) and determined the N-NTD:P3 complex structure at 1.9 Å after adding P3 to the N-NTD crystal and allowing the mixture to rest for 5 min. We determined that the overall structure was in the P212121 orthorhombic space group, showing a tetrameric SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD (monomers A–D) in one asymmetric unit (Fig. S4 A). The statistical data are presented in Table S1. Each monomeric SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD exhibited a structure similar to that previously reported (31,37,38,39). In particular, we found that the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD consisted of a core structure comprising a five-stranded antiparallel β sheet flanked by two short α helices (Fig. S4 B). The basic finger extended from the β-core structure, commonly referred to as the palm. We further observed a distinct, highly positive cleft that presumably creates a putative RNA-binding site located in the hinge/junction region between the palm and the basic finger. These findings were in accordance with those of previous studies of the N protein of other CoVs (31,40).

Figure 2.

The dissociation constant for the interaction of P3 with the SARS-CoV-2 N protein and N-NTD. KD values for the binding of P3 with SARS-CoV-2 (A) N-NTD and (B) N protein. The x axis represents P3 concentration (μM), while the y axis represents relative fluorescence intensity. The data were derived from three independent experiments. SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD was purified in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 50 mM NaCl, while the SARS-CoV-2 N protein was purified in 20 mM Na3PO4 (pH 7.8) and 300 mM NaCl. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

The benzene ring of P3 plays a critical role in mediating interactions

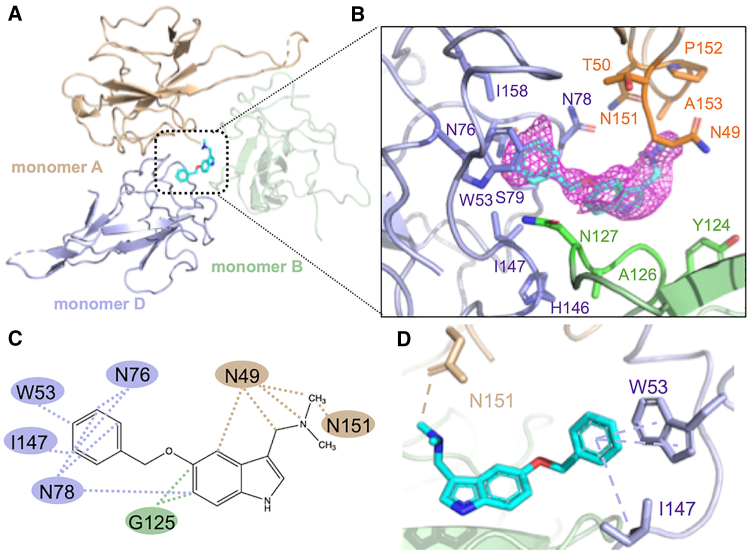

We observed that the P3 compound was located inside the groove in the center of four monomeric SARS-CoV-2 N-NTDs. However, the P3 compound mainly interacted with two monomers (monomers A and D), without any contact with monomer C (Fig. 3 A). Moreover, we noticed that the insertion of P3 into this cavity did not significantly change the native structure, and only N49 on monomer A exhibited a shift with a different angle, while the side chain on I147 also rotated to point at the benzene ring on P3 (Fig. S5). As shown in Table S2, this rotation promoted hydrophobic interactions and a 20.93 Å2 buried surface area (BSA), further supporting the stabilization of P3. To elucidate the interactions between P3 and N-NTD, we analyzed the interfacing residues using PISA (Proteins, Interfaces, Structures, and Assemblies) (41) and the hydrophobic interactions using LigPlot (42). The overall interfacing residues that were in contact with P3 are shown in Fig. 3 B, while the analysis of the BSA is provided in Table S2. We found that P3 was interposed between monomers A and D, contributing to contact areas of 116.65 Å2 and 149.46 Å2, respectively. On monomer A, the amino acids in the hydrophobic binding region consisted of N49 and N151, whereas those on monomer D included W53, I147, N76, and N78 (Fig. 3 C). Notably, we found that π-π and π-alkyl interactions formed between the benzene moiety of P3 and indoles of W53 and I147. Moreover, a carbon-hydrogen bond formed between the P3 side chain and the hydroxyl group on N151 of monomer A (Fig. 3 D). Collectively, we determined that the interfaces between P3 and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD were mainly mediated through hydrophobic interactions, consistent with the drug-design rationale for P3 and CoV N-NTDs (11). Importantly, we observed that the benzene moiety of P3 plays a vital role in the interaction between P3 and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD.

Figure 3.

The crystal structure and interfaces of the SARS-CoV-2-N-NTD:P3 complex. (A) Overall crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3; the monomers A, B, and D are colored in wheat, pale green, and light blue, respectively (B) The residues involved in creating the BSA between P3 and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD. The macromolecular interactions were analyzed using the PISA database. The interacting residues of the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD are indicated. (C) The hydrophobic interactions between P3 and N-NTD are indicated by the dotted lines. The data were validated by analyzing the interactions using LigPlot. (D) The benzene ring of P3 forms π-π and π-alkyl interactions with residues W53 and I147 of chain D of N-NTD, whereas a carbon-hydrogen bond forms between N151 from chain A of N-NTD and the P3 moiety. The data were analyzed using Discovery Studio. To see this figure in color, go online.

Hydrophobic patch for binding with P3 is conserved in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 and remains the primary mechanism for P3 to mediate PPIs

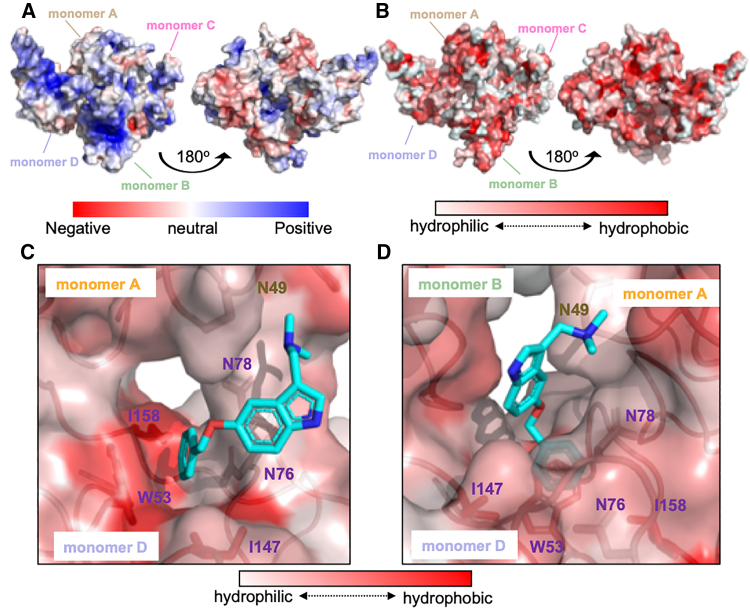

To test whether P3 preferentially interacts with N-NTD through hydrophobic interfaces, we examined the electrostatic surfaces of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTDs (Fig. 4 A). We observed that the overall native protein structure was characterized by a highly charged surface, whereas the cavity at the middle of tetrameric monomers was slightly hydrophobic, enabling the perfect fit of P3 inside the cavity (Fig. 4 B). The hydrophobicity level at the protein surface revealed that the benzene ring of P3 was deeply buried inside a hydrophobic pocket created by the residues surrounding W53 and I147 on monomer D (Fig. 4 C), with the gramine moiety of P3 located under a hydrophobic surface on monomer B (Fig. 4 D). These results demonstrated that the electrostatic surface of the binding region of P3 in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD is highly hydrophobic.

Figure 4.

The benzene ring of P3 compound is embedded within a hydrophobic pocket. (A) The electrostatic surface of the native N-NTD protein structure. (B) The hydrophobicity level of the native protein structure; hydrophobicity was evaluated and colored using PyMOL. (C) The hydrophobic surface between monomers A and D. P3 is located within the center of monomeric A, B, and D. The gramine moiety is located beneath a hydrophobic surface created by chain B. (D) Rotation of 90° of (C) shows that the benzene ring of P3 is inserted into a hydrophobic pocket within monomer D. To see this figure in color, go online.

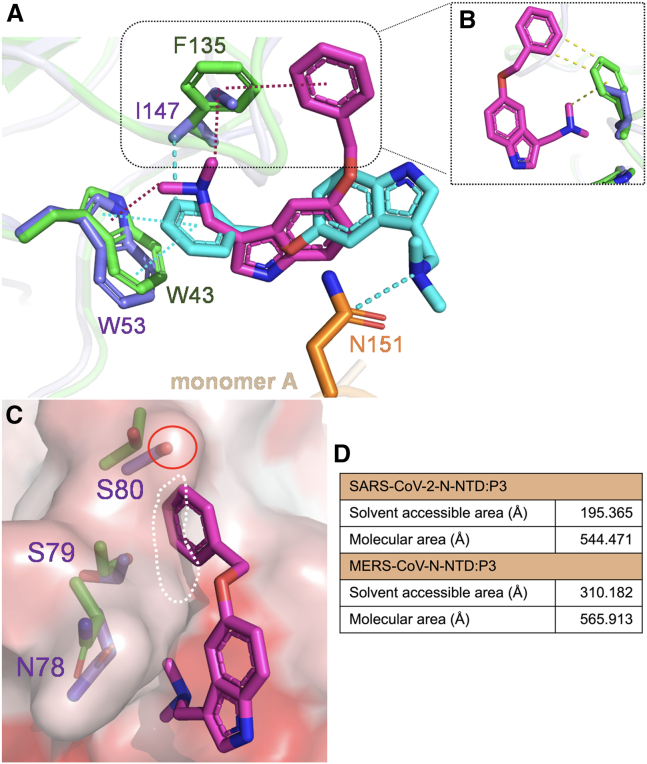

To elucidate the mechanism through which P3 mediates N-NTD structural diversity in CoVs, we compared the interacting residues surrounding P3 in MERS-CoV N-NTD (PDB: 6KL6) and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD examined in this study. As we observed that the N-terminal residue on monomer B of MERS-CoV N-NTD and monomer A of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD are involved in interactions with P3 in both structures, we aligned monomer B of MERS-CoV N-NTD with monomer A of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD. We found that the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between them was 0.699 Å. After superimposition, we observed that the orientation of monomer D in MERS-CoV was rotated by 180° and tilted upward by approximately 30° compared with that in the N-NTD in SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 5 A). We further detected that the N-NTD in SARS-CoV-2 exhibited a more extended N-terminus compared with that in MERS-CoV. Overall, these two monomers had only two identical residues, namely N151 and P152 in SARS-CoV-2, which corresponded to N139 and P140 in MERS-CoV, respectively (Fig. 5 B). We also noticed that in contrast to monomer A of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD, the number of interacting residues was higher in monomer B of MERS-CoV N-NTD (Table S2). We next compared monomer D of MERS-CoV N-NTD with that of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD; the RMSD value was 0.616 Å. Furthermore, we observed that the orientation of monomer A in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD was rotated by 180° compared with that of monomer B in MERS-CoV (Fig. 5 C). We detected that the interacting residues in monomer D were more similar between the two N-NTDs. Specifically, residues W53, N76, N78, S79, and I158 were identical (Fig. 5 D). Overall, although the residues involved in interacting with P3 were highly hydrophobic and conserved, differences in the residues and structures still exist between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTDs.

Figure 5.

Structural comparison of N-NTD:P3 complexes in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. (A) The structures of MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 (PDB: 6KL6) and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 were aligned by superimposing chains B and A from MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complexes, respectively. The MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex is shown in green. RMSD = 0.699 Å (103 to 103 atoms). (B) A close-up view of the interfaces between monomers B and A from MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complexes, respectively; the interacting residues are represented by sticks. (C) The superimposition of monomer D in both complexes. RMSD = 0.616 Å (100 to 100 atoms). The triangle indicates the hydrophobic pocket created by the residues surrounding W53. (D) The interfaces between monomer D in both complexes. The interactions were analyzed using the PISA database. To see this figure in color, go online.

P3 accommodates N-NTD in both MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 by conforming its orientation and structure to the hydrophobic interface

To elucidate the underlying mechanism behind the ability of P3 to interact with the N-NTDs of different CoVs, we aligned monomer D of the N-NTD in MERS-CoV with that in SARS-CoV-2. Our analysis revealed distinct orientations of P3 in these two structures. We found that in the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD, the benzene ring of P3 was positioned forward toward W53 on monomer D, while its dimethylaminomethyl group was further stabilized by N151 on monomer A. By contrast, in the MERS-CoV N-NTD, the dimethylaminomethyl moiety of P3 was oriented toward W43 on monomer D (Fig. 6 A). Additionally, we observed a single substitution of F135 in MERS-CoV with I147 in SARS-CoV-2, which may play a vital role in influencing the position of P3 inside the hydrophobic pocket. First, the distance between the aromatic ring on Phe in MERS-CoV and the dimethylaminomethyl moiety of P3 might be more suitable for forming an interaction compared with the Ile side chain in SARS-CoV-2. This notion suggests that it may be difficult for Ile to engage in a hydrophobic interaction with the dimethylaminomethyl moiety of P3 (Fig. 6 B), which probably results in P3 having a different orientation in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD. We also found that the residues N78–S80 in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD would likely clash with the dimethylaminomethyl moiety of P3 in the MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex. Furthermore, the hydroxyl group on S80 may also repulse the benzene ring of P3. This finding indicated that in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD, these two P3 moieties would point toward different directions (Fig. 6 C). Finally, we measured the surface area inside this pocket using PyMOL. The molecular area in both complexes appeared to be similar. However, in the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complex, the pocket is more hydrophobic than that in the MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex, indicating a preference for the aromatic ring of P3 to be inserted into this cavity (Fig. 6 D). The different hydropathic tendencies between these two pockets could also be a result of a more hydrophobic residue, Ile, in SARS-CoV-2, which substitutes the Phe in MERS-CoV (43). Based on these observations, in the MERS-CoV N-NTD, P3 was constrained by a π-cation interaction between W43 and F135, while W43 simultaneously provided hydrophobic contact with the P3 benzene ring. However, the P3 in the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complex demonstrated a π-π and π-alkyl interaction between the P3 benzene ring and the aromatic rings of W53 and I147 residues. Additionally, we observed that P3 was further stabilized by a carbon-hydrogen bond between its dimethylaminomethyl group and N145 on monomer A.

Figure 6.

Analysis of the mechanism through which P3 interacts with various CoVs. (A) Superimposition of the MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 complexes. The structures of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 and MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 were aligned by superimposing the chain D; RMSD = 0.616 Å (100 to 100 atoms). The interacting residues on the SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complexes are shown in slate blue, orange, and green, respectively. The magenta dashed line represents the π-cation interactions between P3 and MERS-CoV N-NTD; the cyan dashed line represents the π-π and π-alkyl interactions between P3 and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD. (B) The distances between the two P3 moieties and the Phe benzene ring in MERS-CoV N-NTD and the Ile side chain in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD are represented by green and purple colors, respectively. (C) The side chain containing residues N78–S80 is highlighted, and the surface predicted to clash with the benzene ring of P3 in the MERS-CoV N-NTD:P3 complex is shown. (D) The surface area (Å) within the pocket was calculated using PyMOL. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 exerted major global health and socioeconomic implications that reverberate to this day (44). Despite the decreasing intensity of the pandemic, the emergence of new viral variants continues to pose a potential threat to global health. Moreover, coronaviruses, such as PEDV, continue to jeopardize the lives of economically significant animals, resulting in substantial financial losses for swine-raising nations across Asia (45,46). Owing to the significant risks associated with PEDV, preventive immunization is typically performed through the vaccination of pregnant pigs. Nevertheless, the high degree of heterogeneity exhibited by PEDV has rendered the development of effective and safe vaccines for combating this pathogen a considerable challenge (47). Therefore, it is imperative to remain vigilant and prepared for the next CoV outbreak through the development of a pan-CoV inhibitor.

Previously, the P3 compound was established as a potential antiviral agent against MERS-CoV by inducing a non-native PPI between N-NTDs, leading to abnormal aggregation of the N protein (11). Moreover, P3 could inhibit MHV, implying that P3 has broad-spectrum antiviral activities. In this study, we demonstrated that P3 can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in Vero E6 cells, similar to its inhibition of MERS-CoV infection. Furthermore, P3 also demonstrated notable antiviral activity against PEDV (Fig. S6). We determined the SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 structure and elucidated that the hydrophobic pocket surrounding W53 was almost conserved in the N-NTDs of both MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. However, the substitution of F135 (MERS-CoV) with I147 (SARS-CoV-2) probably affected the orientation of P3, despite both Phe and Ile being hydrophobic amino acids. These results demonstrated that despite the low similarities in the N protein and distinct packing arrangements of N-NTD structures between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, P3 demonstrates anti-CoV activity against both CoVs. Furthermore, we used the P3–8 derivatives to confirm the location of P3 and found that it was positioned directly below the N-terminus. Based on a comparison of the 2Fo-Fc maps of both compounds, we identified an extended side chain on the electron density map of P3–8. Consequently, we confirmed that P3–8 was located inside the protein crystal, definitively indicating that P3 positions itself under the N-terminus of monomer A in SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD (Fig. S7). The P3 and P3–8 complexes did not differ significantly; the only notable change included the residue R69 on monomer B forming an additional hydrophobic contact with the side chain of P3–8 (Fig. S8, A and B), contributing to an additional BSA of approximately 29.32 Å2 (Table S2).

In the past, small molecules were not commonly used to modulate PPIs because of a plausible concept that their ability to bind to protein surfaces was limited owing to the absence of specific and well-defined binding pockets, especially in non-native PPIs. As a result, most inhibitors were discovered by chance (48). However, the number of developed PPI-targeting small-molecule inhibitors has recently increased. Approximately 40 small-molecule inhibitors targeting PPIs are currently undergoing preclinical trials, and among them venetoclax, fostemsavir, and lifitegrast have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for clinical use (20,49,50). Recent studies have also applied PPI inhibitors to combat SARS-CoV-2, with most targeting the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein to block viral attachment (51). Despite the promising results of some inhibitors showing large TIs, the high mutation rate of the spike protein, particularly in the RBD, has made it difficult for these inhibitors to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 variants (2,52,53,54,55). By contrast, the low mutation rate of the N protein in CoVs makes it a promising target for antiviral drug design.

In this study, the structure of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 was determined, revealing that hydrophobic interfaces play a crucial role in stabilizing the non-native PPIs for P3. However, the inhibition mechanism and universal antiviral activity of P3 are still unclear and unexplored. Further experimental studies are needed to gain a more detailed understanding of P3’s inhibitory mechanism and its efficacy as a broad-spectrum CoV inhibitor. Overall, although the sequences and structures between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are not identical, our study showed that P3 could fit into the N-NTDs in CoVs by mediating non-native PPI, thus providing evidence that P3 exerts a universal anti-CoV effect.

Data and code availability

The crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD (PDB: 8IQJ), SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 (PDB: 8IV3), and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3-8 (PDB: 8J6X) have been deposited on the Protein Data Bank website.

Author contributions

J.-Y.H., S.-C.L., K.K.-H., and M.-H.H. designed the study. J.-Y.H. and S.-C.L. performed the experiments. K.-M.Z. and S.-Y.L. synthesized the test compounds. H.-Y.W., K.K.-H., S.-Y.L., S.-Y.C., and M.-H.H. provided reagents and contributed analytic tools. J.-Y.H., S.-C.L., and M.-H.H. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (Taiwan) for collecting X-ray diffraction data. This work was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) (NSTC 111-2327-B-005-003, NSTC 109-2311-B-005-007-MY3, and NSTC 109-2628-M-005-001-MY4). This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, R.O.C. under the Higher Education Sprout Project.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Bridget Carragher.

Footnotes

Jhen-Yi Hong and Shih-Chao Lin contributed equally to this work.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2024.01.013.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey W.T., Carabelli A.M., et al. Robertson D.L. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J., Peng P., et al. Huang A.L. Increased immune escape of the new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern omicron. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022;19:293–295. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00836-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBride R., van Zyl M., Fielding B.C. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses. 2014;6:2991–3018. doi: 10.3390/v6082991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang C.K., Hou M.H., et al. Huang T.H. The SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein--forms and functions. Antivir. Res. 2014;103:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang C.K., Sue S.C., et al. Huang T.h. Modular organization of SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006;13:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9035-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo Y.S., Lin S.Y., et al. Hou M.H. Oligomerization of the carboxyl terminal domain of the human coronavirus 229E nucleocapsid protein. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen I.J., Yuann J.M.P., et al. Hou M.H. Crystal structure-based exploration of the important role of Arg106 in the RNA-binding domain of human coronavirus OC43 nucleocapsid protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1834:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng T.Y., Lee K.R., Tarn W.Y. Phosphorylation of the arginine/serine dipeptide-rich motif of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein modulates its multimerization, translation inhibitory activity and cellular localization. FEBS J. 2008;275:4152–4163. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu J.N., Chen J.S., et al. Hou M.H. Targeting the N-terminus domain of the coronavirus nucleocapsid protein induces abnormal oligomerization via allosteric modulation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.871499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin S.M., Lin S.C., et al. Hou M.H. Structure-based stabilization of non-native protein-protein interactions of coronavirus nucleocapsid proteins in antiviral drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:3131–3141. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin S.Y., Liu C.L., et al. Hou M.H. Structural basis for the identification of the N-terminal domain of coronavirus nucleocapsid protein as an antiviral target. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2247–2257. doi: 10.1021/jm500089r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori M., Kovalenko L., et al. Mély Y. Nucleocapsid protein: a desirable target for future therapies against HIV-1. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015;389:53–92. doi: 10.1007/82_2015_433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y., Sneyd H., et al. Wang J. Influenza A virus nucleoprotein: a highly conserved multi-functional viral protein as a hot antiviral drug target. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017;17:2271–2285. doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170224122508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arkin M.R., Tang Y., Wells J.A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:1102–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer G., Rossmann M., Hyvönen M. Alternative modulation of protein-protein interactions by small molecules. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015;35:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flygare J.A., Beresini M., et al. Fairbrother W.J. Discovery of a potent small-molecule antagonist of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins and clinical candidate for the treatment of cancer (GDC-0152) J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:4101–4113. doi: 10.1021/jm300060k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vu B., Wovkulich P., et al. Graves B. Discovery of RG7112: A small-molecule MDM2 inhibitor in clinical development. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:466–469. doi: 10.1021/ml4000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S., Sun W., et al. Debussche L. SAR405838: an optimized inhibitor of MDM2-p53 interaction that induces complete and durable tumor regression. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5855–5865. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souers A.J., Leverson J.D., et al. Elmore S.W. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat. Med. 2013;19:202–208. doi: 10.1038/nm.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong H., Pradhan R.S., et al. Awni W.M. Studying navitoclax, a targeted anticancer drug, in healthy volunteers--ethical considerations and risk/benefit assessments and management. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:3739–3746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White K.M., Abreu P., Jr., et al. Shaw M.L. Broad spectrum inhibitor of influenza A and B viruses targeting the viral nucleoprotein. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018;4:146–157. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosch J. PPI inhibitor and stabilizer development in human diseases. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2017;24:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C.H., Lü W., et al. Gouaux E. NMDA receptor structures reveal subunit arrangement and pore architecture. Nature. 2014;511:191–197. doi: 10.1038/nature13548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammoudeh D.I., Daté M., et al. White S.W. Identification and characterization of an allosteric inhibitory site on dihydropteroate synthase. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:1294–1302. doi: 10.1021/cb500038g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsiang M., Jones G.S., et al. Sakowicz R. New class of HIV-1 integrase (IN) inhibitors with a dual mode of action. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:21189–21203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.347534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessl J.J., Jena N., et al. Kvaratskhelia M. Multimode, cooperative mechanism of action of allosteric HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:16801–16811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.354373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma A., Slaughter A., et al. Kvaratskhelia M. A new class of multimerization selective inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams P.D., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., et al. Terwilliger T.C. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang S., Yang M., et al. Chen S. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein RNA binding domain reveals potential unique drug targeting sites. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:1228–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kudlicki A., Rowicka M., Otwinowski Z. The crystallographic fast Fourier transform. Recursive symmetry reduction. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2007;63:465–480. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307047411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trevor A.J., Masters S.B., Knuidering-Hall M.M. Pharmacology Examination & Board Review. McGraw-Hill Medical; New York: 2013. The therapeutic index is the ratio of the TD50 (or LD50) to the ED50, determined from quantal dose–response curves; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yammine A., Gao J., Kwan A.H. Tryptophan fluorescence quenching assays for measuring protein-ligand binding affinities: principles and a practical guide. Bio. Protoc. 2019;9 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossoehme N.E., Li L., et al. Giedroc D.P. Coronavirus N protein N-terminal domain (NTD) specifically binds the transcriptional regulatory sequence (TRS) and melts TRS-cTRS RNA duplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C.Y., Chang C.K., et al. Huang T.H. Structure of the SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein RNA-binding dimerization domain suggests a mechanism for helical packaging of viral RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saikatendu K.S., Joseph J.S., et al. Kuhn P. Ribonucleocapsid formation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus through molecular action of the N-terminal domain of N protein. J. Virol. 2007;81:3913–3921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02236-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinesh D.C., Chalupska D., et al. Boura E. Structural basis of RNA recognition by the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krissinel E., Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyte J., Doolittle R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu N., Zhang D., et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song D., Park B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Gene. 2012;44:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song D., Moon H., Kang B. Porcine epidemic diarrhea: a review of current epidemiology and available vaccines. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2015;4:166–176. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2015.4.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao Q., Zheng Z., et al. Gong L. The new porcine epidemic diarrhea virus outbreak may mean that existing commercial vaccines are not enough to fully protect against the epidemic strains. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.697839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spencer-Smith R., Koide A., et al. O'Bryan J.P. Inhibition of RAS function through targeting an allosteric regulatory site. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:62–68. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong M., Gadek T.R., et al. Wright J. Discovery and development of potent LFA-1/ICAM-1 antagonist SAR 1118 as an ophthalmic solution for treating dry eye. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:203–206. doi: 10.1021/ml2002482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meanwell N.A., Krystal M.R., et al. Kadow J.F. Inhibitors of HIV-1 attachment: the discovery and development of temsavir and its prodrug fostemsavir. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:62–80. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchwald P. Developing small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions involved in viral entry as potential antivirals for COVID-19. Front Drug Discov. 2022;2 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Beltran W.F., Lam E.C., et al. Balazs A.B. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell. 2021;184:2372–2383.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madhi S.A., Izu A., Pollard A.J. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Vaccine efficacy against the B.1.351 variant. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:571–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2110093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dejnirattisai W., Zhou D., et al. Screaton G.R. Antibody evasion by the P.1 strain of SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2021;184:2939–2954.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahase E. Covid-19: where are we on vaccines and variants? BMJ. 2021;372:n597. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD (PDB: 8IQJ), SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3 (PDB: 8IV3), and SARS-CoV-2 N-NTD:P3-8 (PDB: 8J6X) have been deposited on the Protein Data Bank website.