Abstract

Citrus represents a valuable repository of antioxidant substances that possess the potential for the preservation of meat quality. This meta-analysis aimed to comprehensively assess the impact of citrus additives on the quality and safety of chicken meat. Adhering to the PRISMA protocol, we initially identified 103 relevant studies, from which 20 articles meeting specific criteria were selected for database construction. Through the amalgamation of diverse individual studies, this research provides a comprehensive overview of chicken meat quality and safety, with a specific focus on the influence of citrus-derived additives. Minimal alterations were observed in the nutritional quality of chicken meat concerning storage temperature and duration. The findings demonstrated a significant reduction in aerobic bacterial levels, with Citrus aurantiifolia exhibiting the highest efficacy (P < 0.01). Both extracted and nonextracted citrus components, applied through coating, curing, and marinating, effectively mitigated bacterial contamination. Notably, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) concentrations were significantly reduced, particularly with Citrus hystrix (P < 0.01). Total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN), an indicator of protein degradation, exhibited a decrease, with citrus extract displaying enhanced efficacy (P < 0.01). Chemical composition changes were marginal, except for a protein increase after storage (P < 0.01). Hedonic testing revealed varied preferences, indicating improvements in flavor, juiciness, and overall acceptability after storage (P < 0.01). The study underscores the effectiveness of citrus additives in preserving chicken meat quality, highlighting their antibacterial and antioxidant properties, despite some observed alterations in texture and chemical composition. Citrus additives have been proven successful in 1) mitigating adverse effects on chicken meat during storage, especially with Citrus hystrix exhibiting potent antimicrobial properties, and 2) enhancing the hedonic quality of chicken meat. This research strongly advocates for the application of citrus additives to uphold the quality and safety of chicken meat.

Key words: antioxidant substance, Citrus hystrix, chicken meat quality, storage duration, storage temperature

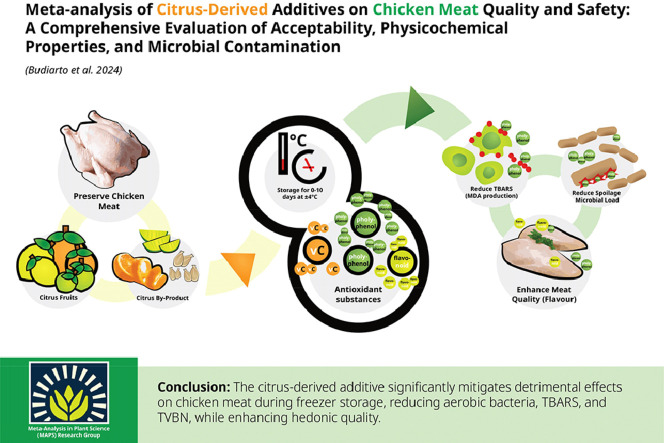

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

The use of a citrus-derived additive results in decreased MDA formation, minimized microbial spoilage, and improved quality of chicken meat

.

INTRODUCTION

Chicken meat products are experiencing rapid growth and are swiftly becoming one of the most rapidly expanding food commodities in numerous regions globally (Chouliara et al., 2007). The surge in popularity of chicken meat products can be attributed to their cost-effective production, a wide variety of commercially processed offerings characterized by low-fat content, high nutritional value, and distinctive flavor (Latou et al., 2014). Nevertheless, owing to its composition marked by elevated moisture and protein levels, along with a high pH, chicken meat proves to be susceptible to the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms and spoilage (Anang et al., 2007). As a result, antioxidant and antimicrobial ingredients are needed to preserve the quality of chicken meat and prevent deterioration.

Consumer demand for minimally processed foods preserved with natural ingredients has increased, while the safety of chemical additives has been questioned. The necessity of preserving food products through the use of natural preservatives and environmentally friendly technologies is evident (Coma, 2008). Many plant extracts containing phenolic compounds have recently gained great popularity and scientific interest as antioxidant and antimicrobial agents (Klangpetch et al., 2016). Several potential natural antioxidant and antimicrobial candidates are derived from Citrus (Lv et al., 2015; Dosoky and Setzer, 2018).

Citrus is an important horticultural commodity worldwide that belongs to Rutaceae, the largest family with more than 200 species (Groppo et al., 2022). Although it is suggested that originates from the Himalayas southeast foothills (Wu et al., 2018), citrus is extensively cultivated in numerous tropical and subtropical regions with its annual production reaching around 102 million tons (Imran et al., 2013; Ben Hsouna et al., 2017). The high production of this fruiting commodity is triggered by the large consumption worldwide since its fruits are delicious, aromatic, and nutrition-rich (Lu et al., 2023).

Citrus fruits serve as abundant reservoirs of beneficial nutrients, including vitamins A (β-cryptoxanthin, α-carotene, and β-carotene), vitamin B-complex (thiamine, pyridoxine, biotin, inositol, and folate), vitamin C (ascorbic acid), and vitamin E (α-tocopherol) (Budiarto et al., 2021), flavonoids, coumarins, limonoids, carotenoids, pectin, limonoid, synephrine, and various other compounds (Lu et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). The proportion of those metabolites in citrus chemical profile differs in response to genotype (Budiarto et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2023) and geographical location (Budiarto et al., 2021; Budiarto and Sholikin, 2022), leading to the variation of its bioactivity, including antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.

Various single reports on citrus phytochemicals and their bioactivity, especially antimicrobial (Cushnie and Lamb, 2005; Waikedre et al., 2010; Ben Hsouna et al., 2017; Denaro et al., 2020; Saleem et al., 2023; Sreepian et al., 2023) have been published recently. For instance, citrus flavonoid are reported to exert intense antioxidant properties (Parhiz et al., 2015), while antibacterial effect are also reported in citrus (Citrus japonica Thunb) peel extract against E. coli (Al-Saman et al., 2019). In practice, citrus essential oils can be used to protect against microbial contaminants in food packaging (Randazzo et al., 2016; Amjadi et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021), and spoilage in chicken meat (Alizadeh et al., 2019; Panahi et al., 2022; Chakoun et al., 2023). However, the results of single reports are still varied and controversial. The single reports generally provide few sample sizes and less statistical power, leading to a less comprehensive conclusion; therefore, a meta-analysis approach to combine numerous earlier reports is carried out to comprehensively evaluate the chicken meat quality and safety treated by citrus or its derivatives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature Search Strategy

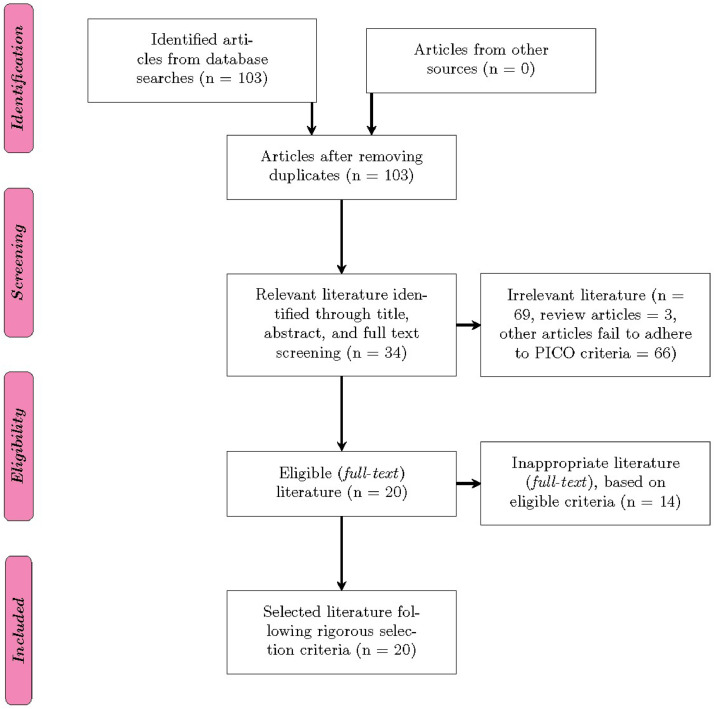

The literature search was conducted without any year restrictions, encompassing literature dating back to 1943 through 2023 from the Scopus database. Browser keyword generation adhered to the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) principle, defined as follows: P = “chicken AND meat”, I = “citrus OR citrus-derived AND additives”, C = “control vs. treatment (addition of citrus OR citrus-derived)”, and O = “meat AND quality (e.g., ‘acceptability’, ‘physicochemical AND properties’, and ‘microbial AND contamination’)” (Page et al., 2021; Adli et al., 2023). A total of 103 potentially relevant articles were identified based on these keyword combinations. Subsequently, several criteria were applied to select eligible literature: 1) articles presenting experimental studies; 2) full-text articles entirely in English; 3) research subjects involving chicken meat; 4) direct comparison between the addition of citrus-derived additives and a control group; 5) parameters encompassing acceptability, including organoleptic testing of chicken meat; 6) physicochemical properties, encompassing the physical and chemical characteristics of chicken; and 7) microbial contamination from aerobic bacteria. After the sorting process of the title, abstract, and full text sections, 34 articles meeting the PICO criteria were obtained. The remaining 69 articles, consisting of 3 review articles and 66 articles not conforming to PICO criteria, were excluded. Subsequently, the 34 articles underwent further selection based on specific criteria. Out of these, 14 articles did not meet the selection criteria, resulting in a total of 20 articles included in the meta-data compilation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Depicts the process of selecting and evaluating articles following the PRISMA protocol (Page et al., 2021).

Compilation and Characteristics of the Database

In this meta-analysis, data for various citrus species were utilized, including Citrus aurantium, Citrus aurantiifolia, Citrus hystrix, Citrus limon, Citrus paradisi, Citrus sinensis, and Citrus unshiu. Recorded initial information in the database encompassed the citrus conditions, citrus components (peel, juice, and seed), citrus forms (nonextracted and extracted), and their respective levels added to chicken meat (% of fresh weight of chicken). Additional details included initial conditions of chicken meat, such as the utilized parts (breast meat, drummettes, whole, and wings), meat forms (fresh, minced, and meatball), pretreatment methods such as cooking processes (uncooked and cooked), and various marination or similar processes (curing, coating, and marinating). Essential information, such as storage duration (days) and storage temperature (°C), was also recorded.

The parameters in the database comprised aerobic bacteria contamination (log10CFU/g), pH, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS; mg/g MDA), and total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN; mg/100 g) of chicken meat. Furthermore, physicochemical characteristics like meat color (a* = redness, b* = yellowness, L* = lightness), hardness (N), moisture (%), ash (%), protein (%), fat (%), and water activity (%) were tabulated. Additionally, hedonic tests, including color, flavor, juiciness, odor, taste, tenderness, and acceptability, were conducted using a 1 to 9 liking scale (higher numbers indicating greater liking). Statistical values obtained from the selected studies included replication or sample size, mean values, and standard deviation. The standard deviation was calculated using the sum of errors of mean and coefficient of variation. Units for each treatment value were standardized, and the data was tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2019 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of research included in the meta-analysis. Contains information regarding the citrus condition (non-extracted or extracted) and the treated conditions of chicken meat.

| Citrus1 | Citrus condition |

Chicken meat condition |

Storage |

References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part2 | Form3 | Addition4 | Part5 | Meat6 | Cooked7 | Marination8 | Temperature (°C) | Duration (days) | ||

| Citrus limon, Citrus paradisi, and Citrus sinensis | Seed | Extracted | 1.5 | Whole | Minced | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-12 | (Adeyemi et al., 2013) |

| Citrus sinensis | Peel | Extracted | 0.3 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4- 27 | 0-9 | (Alahakoon et al., 2013) |

| Citrus sinensis | Peel | Extracted | 0.3 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4- 27 | 0- 9 | (Alahakoon et al., 2015) |

| Citrus aurantium | Juice | Non-extracted | N.D.9 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Cured | N.D. | N.D. | (Al-Hajo, 2009) |

| Citrus limon | Peel | Extracted | N.D. | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Coated | 4 | 12 | (Alizadeh et al., 2019) |

| Citrus sinensis | Peel | Extracted | 0.1 | Whole | Meatball | Cooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-6 | (Borah et al., 2014) |

| Citrus limon | Juice | Extracted | 0.025-1 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-16 | (Chakoun et al., 2023) |

| Citrus limon | Juice | Non-extracted | N.D. | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-7 | (Fouladkhah et al., 2013) |

| Citrus paradisi | Peel | Extracted | 5-100 | Whole | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | N.D. | 0-14 | (Imran et al., 2013) |

| Citrus aurantiifolia, Citrus limon, and Citrus sinensis | Peel | Extracted | 0.4-0.8 | Whole | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 37 | 1 | (Irokanulo et al., 2021) |

| Citrus unshiu | Peel | Extracted | 0.1 | Whole | Fresh | Uncooked and cooked | Marinated | 20 | 0-8 | (Jo et al., 2004) |

| Citrus paradisi | Peel and Seed | Extracted | 0.005-0.02 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked and cooked | Marinated | 19-25 | 0-10 | (Juneja et al., 2006) |

| Citrus paradisi | Seed | Extracted | 0.05-0.5 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Cured | 4 | 0-10 | (Kang et al., 2017) |

| Citrus sinensis | Peel | Extracted | 0.3 | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-7 | (Kim et al., 2015) |

| Citrus hystrix | Peel | Extracted | 0.1-1 | Drummettes | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | 2-14 | (Klangpetch et al., 2016) |

| Citrus limon | Juice | Non-extracted | N.D. | Whole | Fresh | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | <1 | (Kumar et al., 2015) |

| Citrus | N.D. | Extracted | 0.1-0.2 | Breast meat | Minced | Uncooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-14 | (Mexis et al., 2012) |

|

Citrus aurantium and Citrus limon |

Whole | Extracted | 2 | Whole | Fresh | Uncooked | Coated | 4 | 0-16 | (Panahi et al., 2022) |

| Citrus | N.D. | Extracted | 0.025 | Breast meat and wings | Fresh | Uncooked and cooked | Marinated | 4 | 0-90 | (Rimini et al., 2014) |

| Citrus unshiu | Peel | Extracted | N.D. | Breast meat | Fresh | Uncooked | Coated | 5 | 0-5 | (Seol et al., 2013) |

Citrus is a species of citrus, and the term “Citrus” itself denotes an unidentified type.

A component of citrus refers to the parts utilized in experiments, including whole, juice, peel, and seed.

The form of citrus fruit can be either non-extracted or extracted.

The addition of citrus to chicken meat is measured as a percentage of its fresh weight.

A segment of chicken meat used in experiments includes whole, breast meat, wings, and drummettes.

Meat takes various forms such as fresh, minced, and meatball in the context of chicken.

Cooked denotes the cooking process of chicken samples, whether they are cooked or uncooked.

Marination involves applying citrus additives to chicken meat and includes marinated, coated, and cured methods.

N.D. stands for no data available.

Data Analysis and Validation

The effect size, expressed as “Hedges d” was employed to measure the parameter distance between the control and the addition of additive citrus to chicken meat (Marín-Martínez and Sánchez-Meca, 2010). The selection of this method was made due to its capability to calculate the effect size without considering heterogeneity in sample size, measurement units, and statistical test results, as well as its suitability for evaluating the effect of paired treatments. The control group represented the treatment without the addition of additive citrus (), while the treatment group received additive citrus (). The following outlines the meta-analysis calculation method according to (Wallace et al., 2012). The effect size () was calculated as:

| (1) |

where is the mean value from the experimental group, and is the mean value of the control group. Therefore, a positive effect size indicates that the observed parameter is greater in the experimental group, and vice versa. is the correction factor for small sample size, i.e.,

| (2) |

and is the pooled standard deviation, defined as:

| (3) |

where is the sample size of the experimental group, is the sample size of the control group, is the standard deviation of the experimental group, and is the standard deviation of the control group. The variance of is described as:

| (4) |

The cumulative effect size is formulated as:

| (5) |

where is the effect size of each study, is the sample variance, and is the inverse of the sample variance: . The precision of the effect size is described using the 95% confidence interval (CI), that is, , and is the deviation calculated with the correction factor so that its value is equal to . The calculated effect size is considered significant if the CI does not reach the null effect size. The limits of the sum of effect size or standardized mean difference (SMD) are used as standard judgment borders to indicate how large the effect size is, that is, (0 ≤ SMD < 0.2) for a small effect, (0.2 ≤ SMD < 0.5) for a medium effect, and (SMD > 0.5) for a large effect. A positive indication of the SMD (often omitted) signifies a favorable effect of the treatment resulting from the intervention, while conversely, a negative sign suggests an adverse impact. An additional computation of cumulative effect size was employed for various variable categories, including citrus varieties, extraction processes, chicken meat portions, application techniques, and storage duration. This was carried out to examine the influence of moderator variables on the final effect size. All the above effect size-related calculations were performed using OpenMEE (Wallace et al., 2017).

RESULTS

Aerobic Bacteria

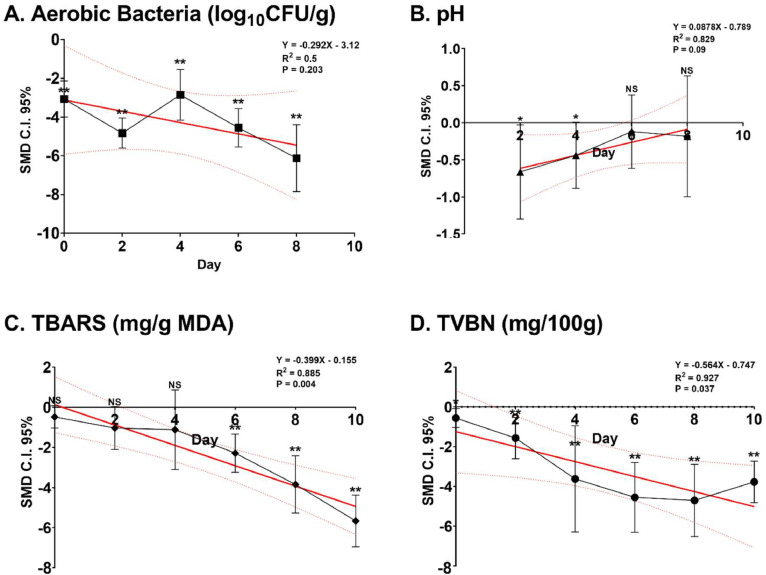

The decrease in aerobic bacteria levels in chicken meat resulting from the application of citrus additives as compared to the control is presented in Table 2. Substantial differences in effects were recorded from 79 observed data points. There was a significant decrease in the population of aerobic bacteria (log10CFU/g) in chicken meat treated with citrus (P < 0.001). Citrus aurantiifolia demonstrated the highest cumulative effect on the reduction of aerobic bacteria compared to other citrus types, while Citrus paradisi exhibited the lowest (P < 0.05). Both extracted and nonextracted citrus were effective in reducing aerobic bacterial contamination (P < 0.001). Different parts of chicken meat, namely breast meat, drummettes, and whole, showed a positive response to the reduction of aerobic bacteria (P < 0.001). The application of citrus using coating, curing, and marinating techniques was capable of reducing the population of aerobic bacteria, with marinating being the most effective technique (P < 0.001). The varying storage durations (from 0 to 8 d) revealed a decreasing regression trend in the population of aerobic bacteria due to citrus additives (P = 0.203; R2 = 0.5; Figure 2A). During the storage intervals of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 d for the preserved chicken meat, there was a noteworthy reduction in aerobic bacteria attributable to citrus treatment when compared to the untreated group (P < 0.01). The daily reduction rate was 0.292 log10CFU/g.

Table 2.

Citrus pretreatment effects on aerobic bacterial contamination in chicken meat.

| NDP1 | Effect size |

Heterogeneity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% C.I.) | Std Error | P value | I² (%) | P value | ||

| Aerobic bacteria (log10CFU/g) | 79 | −5 (−5.65 to −4.35) | 0.33 | <0.01 | 82.3 | <0.01 |

| Citrus | ||||||

| Citrus aurantiifolia | 9 | −11.1 (−14.7 to −7.5) | 1.83 | <0.01 | 63.5 | <0.01 |

| Citrus aurantium | 1 | −1.6 (−3.44 to 0.24) | 0.94 | - | - | - |

| Citrus aurantium and Citrus limon | 1 | −2.85 (−5.13 to −0.58) | 1.16 | - | - | - |

| Citrus hystrix | 21 | −5.88 (−6.73 to −5.02) | 0.44 | <0.01 | 4.1 | 0.41 |

| Citrus limon | 12 | −5.65 (−6.98 to −4.32) | 0.68 | <0.01 | 36.3 | 0.1 |

| Citrus paradisi | 10 | −2.01 (−3.42 to −0.59) | 0.72 | <0.01 | 80.4 | <0.01 |

| Citrus sinensis | 24 | −4.5 (−5.43 to −3.57) | 0.47 | <0.01 | 87.1 | <0.01 |

| Citrus unshiu | 1 | −1.49 (−3.3 to 0.32) | 0.92 | - | - | - |

| Extraction | ||||||

| Extracted | 77 | −5.01 (−5.68 to −4.35) | 0.34 | <0.01 | 82.7 | <0.01 |

| Non-extracted | 2 | −4.54 (−6.7 to −2.38) | 1.1 | <0.01 | - | 0.53 |

| Chicken meat | ||||||

| Breast meat | 28 | −3.71 (−4.65 to −2.77) | 0.48 | <0.01 | 90.2 | <0.01 |

| Drummettes | 21 | −5.88 (−6.73 to −5.02) | 0.44 | <0.01 | 4.1 | 0.41 |

| Whole | 30 | −5.83 (−7.01 to −4.64) | 0.61 | <0.01 | 68.5 | <0.01 |

| Application | ||||||

| Coated | 4 | −1.9 (−2.88 to −0.93) | 0.5 | <0.01 | - | 0.81 |

| Cured | 4 | −4.34 (−5.85 to −2.83) | 0.77 | <0.01 | - | 0.45 |

| Marinated | 71 | −5.28 (−5.99 to −4.56) | 0.36 | <0.01 | 83.6 | <0.01 |

NDP: observed data analyzed in meta study.

Figure 2.

Impact of pretreatment citrus on chicken meat. Standardized mean difference (sum of effect size) on aerobic bacteria, pH, TBARS, and TVBN during 8-day storage with parameter measurements conducted at 2-day intervals.

pH

The pH level of the chicken meat experienced a reducing trend because of the citrus treatment, exhibiting a moderate impact in comparison to the control (P = 0.056; Table 3). No significant changes were observed in the treatment factors, including the variety of citrus, extraction process, and sample part of chicken meat (P > 0.05). The use of coating technique on chicken meat resulted in a significant decrease in pH (P = 0.002). The storage duration also showed a slight impact on pH, with overall citrus not affecting pH from d 2 to 8 of storage (P = 0.09; Figure 2B). However, on days 2 and 4, the utilization of citrus resulted in a decrease in the pH of the chicken meat compared to the control, with a statistical significance (P < 0.05). The pH experienced a daily decline at a rate of 0.0878 pH units.

Table 3.

The pH values of chicken meat subjected to citrus pretreatment.

| NDP1 | Effect size |

Heterogeneity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% C.I.) | Std error | P value | I² (%) | P value | ||

| pH | 44 | −0.46 (−0.94 to 0.01) | 0.24 | 0.06 | 81.7 | <0.01 |

| Citrus | ||||||

| Citrus2 | 10 | 0.07 (−0.15 to 0.29) | 0.12 | 0.54 | - | 0.78 |

| Citrus aurantium | 1 | −1.1 (−2.82 to 0.62) | 0.88 | - | - | - |

| Citrus aurantium and Citrus limon | 1 | −1.92 (−3.86 to 0.01) | 0.99 | - | - | - |

| Citrus hystrix | 21 | 0 (−0.35 to 0.35) | 0.18 | 0.99 | - | 1 |

| Citrus limon | 3 | −8.83 (−20.06 to 2.4) | 5.73 | 0.12 | 98 | <0.01 |

| Citrus paradisi | 4 | 9.76 (−4.2 to 23.72) | 7.12 | 0.17 | 92.8 | <0.01 |

| Citrus sinensis | 3 | 0.15 (−0.78 to 1.08) | 0.47 | 0.76 | - | 0.85 |

| Citrus unshiu | 1 | −5.21 (−8.57 to -1.86) | 1.71 | - | - | - |

| Extraction | ||||||

| Extracted | 43 | −0.12 (−0.41 to 0.17) | 0.15 | 0.4 | 46.5 | <0.01 |

| Non-extracted | 1 | −19.2 (−22.2 to -16.2) | 1.54 | - | - | - |

| Chicken meat | ||||||

| Breast meat | 16 | −0.33 (−1.13 to 0.47) | 0.41 | 0.42 | 78.2 | <0.01 |

| Drummettes | 21 | 0 (−0.35 to 0.35) | 0.18 | 0.99 | - | 1 |

| Whole | 4 | −5.8 (−12.2 to 0.57) | 3.25 | 0.07 | 97.5 | <0.01 |

| Wings | 3 | 0.16 (−0.17 to 0.49) | 0.17 | 0.34 | - | 0.59 |

| Application | ||||||

| Coated | 5 | −2.52 (−4.08 to -0.96) | 0.8 | < 0.01 | 56.8 | 0.06 |

| Cured | 4 | 9.76 (−4.2 to 23.72) | 7.12 | 0.17 | 92.8 | <0.01 |

| Marinated | 35 | −0.29 (−0.73 to 0.15) | 0.23 | 0.2 | 79.1 | <0.01 |

NDP, observed data analyzed in meta study.

Citrus, unconfirmed varieties of the citrus.

Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances

The administration of citrus treatment, as compared to the control group, led to a noteworthy decrease in TBARS values (P < 0.001; Table 4). Among the citrus types, Citrus hystrix exhibited the highest decrease in TBARS, followed by Citrus limon, Citrus paradisi, and citrus (unconfirmed variety). Furthermore, the extracted form of citrus had a significant effect on reducing TBARS (P < 0.001). Similarly, drummettes, whole, and wings of chicken meat showed similar significant effects (P < 0.001). Curing and marination had a more pronounced effect on reducing TBARS in chicken meat (P < 0.001) (Figure 2C). During the 10-d treatment period, administered at 2-d intervals, the use of citrus resulted in a notable reduction in TBARS levels (P = 0.004). Nevertheless, the substantial effects of citrus in lowering TBARS were only observed on d 6, 8, and 10 in comparison to the control group (P < 0.01). The rate of TBARS reduction was 0.399 mg/g DMA in a day, with MDA representing malondialdehyde.

Table 4.

Chicken meat thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) concentrations after citrus pretreatment.

| NDP1 | Effect size |

Heterogeneity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% C.I.) | Std Error | P value | I² (%) | P value | ||

| TBARS (mg/g MDA) | 56 | −2.57 (−3.24 to −1.9) | 0.34 | < 0.01 | 91.3 | < 0.01 |

| Citrus | ||||||

| Citrus2 | 4 | −1.37 (−1.86 to −0.88) | 0.25 | < 0.01 | 58.1 | 0.07 |

| Citrus hystrix | 21 | −7.54 (−8.56 to −6.52) | 0.52 | < 0.01 | - | 0.87 |

| Citrus limon | 2 | −6.18 (−8.98 to −3.38) | 1.43 | < 0.01 | 24.1 | 0.25 |

| Citrus paradisi | 9 | −2.78 (−4.34 to −1.22) | 0.8 | < 0.01 | 78.6 | < 0.01 |

| Citrus sinensis | 15 | 0.74 (−0.05 to 1.53) | 0.4 | 0.07 | 92.2 | < 0.01 |

| Citrus unshiu | 5 | −2.89 (−6.4 to 0.62) | 1.79 | 0.11 | 87.5 | < 0.01 |

| Extraction | ||||||

| Extracted | 56 | −2.57 (−3.24 to −1.9) | 0.34 | < 0.01 | 91.3 | < 0.01 |

| Chicken meat | ||||||

| Breast meat | 22 | 0.01 (−0.74 to 0.75) | 0.38 | 0.99 | 92.8 | < 0.01 |

| Drummettes | 21 | −7.54 (−8.56 to −6.52) | 0.52 | < 0.01 | - | 0.87 |

| Whole | 11 | −4.04 (−6.18 to −1.89) | 1.1 | < 0.01 | 86.2 | < 0.01 |

| Wings | 2 | −0.99 (−1.42 to −0.57) | 0.22 | < 0.01 | - | 0.67 |

| Application | ||||||

| Coated | 1 | −2.06 (−4.05 to −0.08) | 1.01 | - | - | - |

| Cured | 4 | −4.36 (−5.85 to −2.88) | 0.76 | < 0.01 | - | 0.81 |

| Marinated | 51 | −2.41 (−3.1 to −1.71) | 0.36 | < 0.01 | 91.6 | < 0.01 |

NDP, observed data analyzed in meta study.

Citrus, unconfirmed varieties of the citrus.

Total Volatile Base Nitrogen

In the conducted meta-analysis, the inclusion of citrus compared to the control resulted in a noteworthy reduction in TVBN levels (P < 0.001; Table 5). A notable reduction effect was also observed with an unspecified type of citrus (P = 0.05). The application of citrus in the form of extract, coating, or marination techniques proved highly effective in reducing volatile nitrogen (P < 0.05). Consistently, both breast meat and whole chicken meat exhibited a positive response to the reduction of TVBN due to the citrus additive (P < 0.05). Over a 10-d storage period, TVBN levels in chicken meat significantly decreased as a result of the citrus treatment (P = 0.037; Figure 2D). Additionally, at time points 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, citrus significantly lowered TVBN levels in chicken meat compared to the control (P < 0.05). It was recorded that the decrease rate of TVBN was 0.564 mg/100 g (per day).

Table 5.

Total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN) in chicken meat treated with citrus.

| NDP1 | Effect size |

Heterogeneity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% C.I.) | Std error | P value | I² (%) | P value | ||

| TVBN (mg/100g) | 12 | −1.97 (−3.09 to −0.85) | 0.57 | < 0.01 | 69.5 | - |

| Citrus | ||||||

| Citrus2 | 4 | −2.68 (−5.35 to 0) | 1.4 | 0.05 | 80 | < 0.01 |

| Citrus aurantium | 1 | −5 (−8.26 to −1.75) | 1.7 | - | - | - |

| Citrus aurantium and Citrus limon | 1 | −6.91 (−11.1 to −2.68) | 2.2 | - | - | - |

| Citrus limon | 1 | −5.18 (−8.52 to −1.84) | 1.7 | - | - | - |

| Citrus paradisi | 4 | −0.71 (−1.54 to 0.11) | 0.42 | 0.09 | - | 0.99 |

| Citrus unshiu | 1 | −0.07 (−1.67 to 1.53) | 0.82 | - | - | - |

| Extraction | ||||||

| Extracted | 12 | −1.97 (−3.09 to −0.85) | 0.57 | < 0.01 | 69.5 | < 0.01 |

| Chicken meat | ||||||

| Breast meat | 9 | −1.03 (−1.94 to −0.13) | 0.46 | 0.03 | 52 | 0.03 |

| Whole | 3 | −5.51 (−7.56 to −3.47) | 1.04 | < 0.01 | - | 0.76 |

| Application | ||||||

| Coated | 4 | −4.01 (−7.57 to −0.46) | 1.8 | 0.03 | 82.8 | < 0.01 |

| Cured | 4 | −0.71 (−1.54 to 0.11) | 0.42 | 0.09 | - | 0.99 |

| Marinated | 4 | −2.68 (−5.35 to 0) | 1.36 | 0.05 | 79.9 | < 0.01 |

NDP, observed data analyzed in meta study.

Citrus, unconfirmed varieties of the citrus.

Meat Color, Hardness, and Chemical Composition

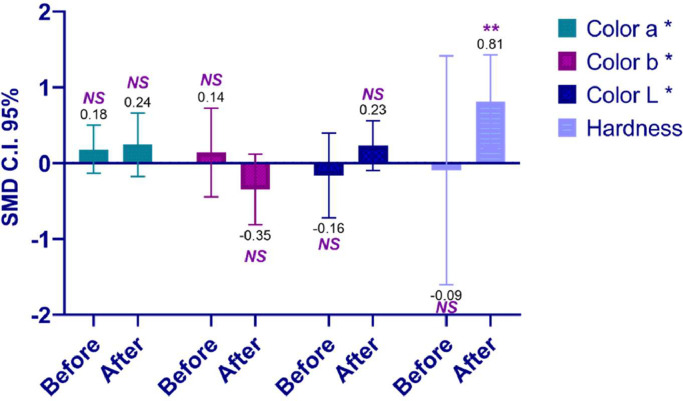

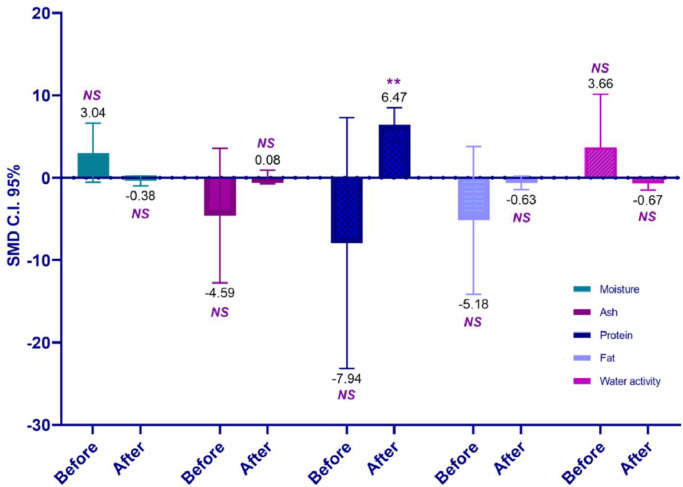

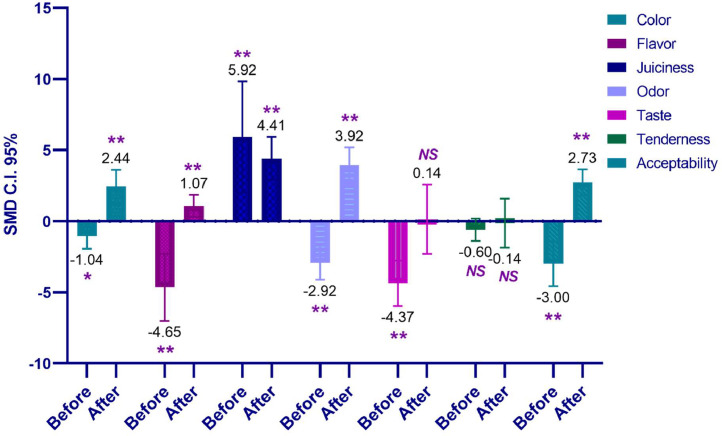

The addition of citrus significantly increased the hardness of chicken meat with a notable effect observed after storage (P < 0.01; Table 7; Figure 3). However, a similar effect was not observed in either the color of the meat (before and after storage) or the hardness (after storage; Tables 6 and 7). The comparison between citrus and the control did not substantially alter the chemical composition of chicken meat, except for a significant change in the protein parameter after the storage period (P < 0.001; Table 7; Figure 4).

Table 7.

Physicochemical quality and hedonic testing of chicken meat treated with citrus pretreatment (after storage).

| Parameter | NDP1 | Effect size |

Heterogeneity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% C.I.) | Std error | P value | I² (%) | P value | ||

| Meat color and hardness | ||||||

| Color a* | 19 | 0.24 (−0.18 to 0.66) | 0.21 | 0.26 | 53.6 | 0.15 |

| Color b* | 15 | −0.35 (−0.81 to 0.12) | 0.24 | 0.14 | 59.5 | <0.01 |

| Color L* | 19 | 0.23 (−0.1 to 0.56) | 0.17 | 0.17 | 30 | 0.11 |

| Hardness | 7 | 0.81 (0.19 to 1.43) | 0.32 | 0.01 | - | 0.69 |

| Chemical properties | ||||||

| Moisture | 12 | −0.38 (−0.98 to 0.23) | 0.31 | 0.22 | 77.5 | <0.01 |

| Ash | 4 | 0.08 (−0.73 to 0.89) | 0.41 | 0.84 | - | 0.86 |

| Protein | 4 | 6.47 (4.44 to 8.49) | 1.03 | < 0.01 | - | 0.71 |

| Fat | 4 | −0.63 (−1.45 to 0.19) | 0.42 | 0.14 | - | 0.91 |

| Water activity | 4 | −0.67 (−1.51 to 0.18) | 0.43 | 0.12 | - | 0.44 |

| Hedonic test | ||||||

| Color | 4 | 2.44 (1.25 to 3.63) | 0.61 | < 0.01 | 13.9 | 0.32 |

| Flavor | 5 | 1.07 (0.3 to 1.85) | 0.39 | 0.01 | - | 0.9 |

| Juiciness | 4 | 4.41 (2.89 to 5.93) | 0.78 | <0.01 | - | 0.5 |

| Odor | 35 | 3.92 (2.66 to 5.19) | 0.65 | <0.01 | 80.5 | <0.01 |

| Taste | 13 | 0.14 (−2.3 to 2.59) | 1.25 | 0.91 | 87.5 | <0.01 |

| Tenderness | 14 | −0.14 (−1.87 to 1.58) | 0.88 | 0.87 | 83.4 | <0.01 |

| Acceptability | 29 | 2.73 (1.8 to 3.65) | 0.47 | <0.01 | 75.1 | <0.01 |

NDP, observed data analyzed in meta study.

Figure 3.

Impact of pretreatment with citrus on the color and hardness of chicken meat, conditions before and after storage.

Table 6.

Physicochemical quality and hedonic test of chicken meat treated with citrus pretreatment (before storage).

| Parameter | NDP1 | Effect size |

Heterogeneity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% C.I.) | Std error | P value | I² (%) | P value | ||

| Meat color and hardness | ||||||

| Color a* | 12 | 0.18 (−0.14 to 0.5) | 0.16 | 0.26 | - | 0.99 |

| Color b* | 8 | 0.14 (−0.45 to 0.73) | 0.3 | 0.64 | 46.6 | 0.07 |

| Color L* | 12 | −0.16 (−0.72 to 0.4) | 0.29 | 0.57 | 50.1 | 0.02 |

| Hardness | 5 | −0.09 (−1.61 to 1.42) | 0.77 | 0.9 | 94.3 | <0.01 |

| Chemical properties | ||||||

| Moisture | 6 | 3.04 (−0.55 to 6.63) | 1.83 | 0.1 | 96 | <0.01 |

| Ash | 2 | −4.59 (−12.76 to 3.57) | 4.16 | 0.27 | 98.3 | <0.01 |

| Protein | 2 | −7.94 (−23.16 to 7.28) | 7.77 | 0.31 | 99.1 | <0.01 |

| Fat | 2 | −5.18 (−14.14 to 3.78) | 4.57 | 0.26 | 98.4 | <0.01 |

| Water activity | 2 | 3.66 (−2.84 to 10.15) | 3.31 | 0.27 | 97.7 | <0.01 |

| Hedonic test | ||||||

| Color | 18 | −1.04 (−1.93 to −0.14) | 0.46 | 0.02 | 83.6 | <0.01 |

| Flavor | 18 | −4.65 (−7.01 to −2.28) | 1.21 | <0.01 | 92.9 | <0.01 |

| Juiciness | 4 | 5.92 (2.02 to 9.83) | 1.99 | <0.01 | 80.7 | <0.01 |

| Odor | 24 | −2.92 (−4.12 to −1.72) | 0.61 | <0.01 | 83.3 | <0.01 |

| Taste | 87 | −4.37 (−5.97 to −2.76) | 0.82 | <0.01 | 86.5 | <0.01 |

| Tenderness | 21 | −0.6 (−1.39 to 0.19) | 0.4 | 0.14 | 79.1 | <0.01 |

| Acceptability | 24 | −3 (−4.57 to −1.42) | 0.81 | <0.01 | 91 | <0.01 |

NDP, observed data analyzed in meta study.

Figure 4.

Impact of pretreatment citrus effect on the water, ash, protein, and fat composition of chicken meat, conditions before and after storage.

Hedonic Test

The hedonic evaluation of the citrus additive conducted prior to storage is presented in Table 6. The parameters including color, flavor, juiciness, odor, taste, and acceptability of chicken meat exhibited significantly lower values compared to the control group (P < 0.05), except for juiciness, which showed a rapid increase. In contrast, the hedonic evaluation of citrus vs. control treatment after storage at approximately 4°C revealed significant improvements in color, flavor, juiciness, odor, and acceptability (P < 0.01), particularly for juiciness. Most SMD values were negative before the storage process, while the opposite was observed during the storage (Figure 5). The parameter with the most pronounced effect, both before and after storage, was juiciness.

Figure 5.

cumulative effect size of pretreatment citrus on hedonic ratings (1 to 9, with 9 indicating the highest preference) of chicken meat, conditions before and after storage.

DISCUSSION

Aerobic Bacteria

Nearly 8% of meat and meat product damage is attributed to spoilage (Höll et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020). Meat spoilage encompasses physical and chemical deterioration, as well as changes in texture and appearance (Odeyemi et al., 2020). Certain bacteria from the genera Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Brochothrix, Moraxella, Shewanella, and Pseudomonas are considered dominant communities in chilled and aerobically packaged meat and poultry (Wang et al., 2017, 2021; Odeyemi et al., 2020). Citrus, as a beneficial additive, is effective in reducing aerobic bacterial contamination. The population of aerobic bacteria in frozen chicken meat decreases during storage, and almost all citrus types exhibit antibacterial and antioxidant activities. For instance, Citrus hystrix is reported to contain limonin, syringaresinol, and tamarin, which act as inhibitors for bacteria from the genera Acinetobacter, Candida, Cryptococcus, and Staphylococcus (Waikedre et al., 2010; Panthong et al., 2013; Budiarto et al., 2021; Budiarto and Sholikin, 2022; Zhao et al., 2023). Similarly, recent studies report that the essential oils of Citrus reticulata, Citrus paradisi, and Citrus lemon can inhibit the growth of bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, Candida albicans, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella abony, and Staphylococcus aureus (Denkova-Kostova et al., 2021). In addition to being effective against nonresistant bacteria, citrus also exhibits antibacterial activity against resistant strains. For example, Citrus hystrix essential oil can reduce the emergence of resistant bacteria. Recent research reveals that the essential oil from Citrus hystrix is effective in inhibiting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus within 12 h per dose (MIC = 18.3 mg/mL) (Sreepian et al., 2023). Cross-contamination from the on-farm and preprocessing sectors of chicken meat products is crucial because many spoilage microorganisms, particularly from the aerobic group, contribute significantly to meat deterioration. Additionally, issues of bacterial or other microbial resistance should be carefully considered (Shao et al., 2021).

It cannot be ignored that certain essential oils, flavonoids, and polyphenols from citrus provide antibacterial benefits. The administration of grapefruit seed extract is effective in reducing the population of spoilage bacteria, comparable to the synthetic preservative mixture of 0.2% sorbic acid and 70 ppm sodium nitrite (Kang et al., 2017). Extracts from Citrus aurantium and Citrus lemon with alginate coating reduce the population of Pseudomonas spp. compared to the control. Citrus extracts prove to be the most effective treatment in inhibiting Pseudomonas spp., likely due to the antimicrobial action of alginate and extracts (Panahi et al., 2022). The antimicrobial activity of citrus is likely attributed to the reaction of extract compounds with the cell membrane and bacterial cell wall, resulting in increased membrane permeability and leakage from the cell wall, membrane swelling, reduced membrane function due to enzyme activity inhibition, and also the bacteria diminished ability to absorb nutrients, preventing their growth and development (Budiarto and Sholikin, 2022; Venkatachalam et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

pH

Chicken meat stored at low temperatures will undergo an increase in pH due to spoilage activity (Marcinkowska-Lesiak et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2018). While citrus initially may impart acidity to chicken meat leading to a decrease in pH, after being stored for 10 days, there is a non-significant increase in the meat pH. This presents a novel understanding that citrus might inhibit the growth of spoilage bacteria by creating acidic conditions (Rimini et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2015; Charmpi et al., 2020; Ben Braïek and Smaoui, 2021). However, no significant changes are observed in treatment factors such as citrus variety, extraction process, and chicken meat sample part. Nonetheless, the application of the coating technique on chicken meat results in an optimal pH reduction compared to other methods.

To elaborate, this pH reduction could be attributed to the acidic nature of citrus components interacting with the meat (Charmpi et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2023). The coating technique, likely enhancing the contact between citrus and the meat surface, produces a more pronounced decrease in pH. Variations observed on specific storage days may be linked to the dynamic properties of citrus compounds and their interaction with the meat matrix. Further research into the specific chemical reactions and mechanisms involved in pH modulation by citrus additives could provide valuable insights for optimizing these techniques in poultry processing.

Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances

Flavonoids and polyphenols serve as antioxidants against oxidative stress, protecting Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells from damage induced by H2O2 free radicals (Stagos, 2019). Most citrus components, including benzene, carotenoids, coumarins, flavonoids, limonoids, minerals, pectin's, quinolinone, vitamins, and other compounds, exhibit antioxidant activity (Seol et al., 2013; Saleem et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). It is reported that 80% ethanol extract from Citrus limon peel has the ability to neutralize free radicals by 78.6 to 93.1%, even more effectively than orange and grapefruit peel ethanol extracts (Saleem et al., 2023). Meta-analysis results are consistent with these findings, showing a significant reduction in lipid oxidation, presented in mg/g of malondialdehyde (MDA), in citrus-treated vs. control chicken meat. Citrus hystrix demonstrated the most pronounced decrease in MDA, followed by Citrus limon and Citrus paradisi. Components such as hydroxynoracronycine and syringaresinol from Citrus hystrix exhibit antioxidant activity in the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl scavenging activity (DPPH) test with IC50 values of 0.19 and 0.032 mg/mL (Panthong et al., 2013). Additionally, treatment with Citrus hystrix extract at the level of 50 µg/mL decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) from H2O2-induced ROS formation (Klangpetch et al., 2016; Ratanachamnong et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Therefore, numerous antioxidant components from citrus, both in extracted and non-extracted forms (such as vitamin C), can be applied as natural antioxidants to reduce oxidative damage in frozen chicken meat storage. The application in the form of curing and marination, as shown in this meta-data analysis, demonstrates a significant decrease in MDA, regardless of the chicken meat part intended for preservation.

Regarding the explanation of the mechanism of lipid oxidation reduction in chicken meat during storage, there are various references due to the variation in antioxidant components of each citrus and their extraction processes. For example, Citrus limon peel, when extracted with 80% ethanol, produces flavonoid compounds capable of capturing free radicals by donating their free electrons, thereby preventing chain reactions caused by free radicals (Saleem et al., 2023; Venkatachalam et al., 2023). Meanwhile, if only the juice of such citrus is utilized, components like vitamin C dominate, and vitamin C serves as a natural antioxidant standard (Padayatty et al., 2003; Patil et al., 2017; Borghi and Pavanelli, 2023; Gęgotek and Skrzydlewska, 2023). In brief, both the main fruit and by-products of citrus can be utilized as antioxidants to reduce the prevalence of lipid damage in meat products.

Total Volatile Base Nitrogen

TVBN values have been extensively utilized for assessing meat deterioration alongside TBARS measurements, as highlighted by Moura-Alves et al. (2023). Serving as a biomarker for protein and amine degradation, TVBN is commonly employed to evaluate meat freshness, as emphasized by Bekhit et al. (2021). Our meta-analysis indicates that the application of citrus through diverse methods such as coating, curing, and marinating tends to reduce TVBN levels in meat. The efficacy of TVBN reduction is significantly improved when employing the extract method. In accordance with the TBARS parameter, the rationale behind the decrease in TVBN levels aligns with the previously mentioned explanation. Citrus polyphenols and flavonoids, recognized as antioxidants (Zou et al., 2016; Carr and Rowe, 2020), are generally effective in alleviating meat deterioration. The decline in TVBN levels is closely linked to the antimicrobial activity of citrus and its extract. Ben Hsouna et al. (2017) observed that phytochemical compounds, particularly in citrus essential oils, are responsible for the antimicrobial activity. Citrus peel extracts disrupt cellular protein synthesis by forming irreversible complexes with proline-rich proteins, as demonstrated by Espina et al., (2011). Therefore, understanding the biological properties exhibited by extracts rich in flavonoids or phenolic acids can elucidate the antimicrobial activity against bacterial proliferation (Martínez-Zamora et al., 2021).

Meat Color, Hardness, and Chemical Composition

Regarding the meat color (L*, a*, and b*) during refrigerated storage and the addition of citrus additives, there is no change at all, as indicated by meta-analysis testing. Chicken meat retains its color after being stored in the cold storage due to several factors. Initially, the refrigerator with low temperature is essential for preserving color by stabilizing pigments and decreasing enzyme activity (Marcinkowska-Lesiak et al., 2016; Ab Aziz et al., 2020). In alignment with prior research, meat preserved using vacuum packaging demonstrates stability in the b* parameter value up to day 10, followed by an almost 4-fold increase on d 15 at a storage temperature of 2°C (Marcinkowska-Lesiak et al., 2016). The rise in the b* parameter value is linked to the synthesis of metmyoglobin, a compound that typically contributes to color changes in meat, occurring during extended periods of cold storage (Jouki and Khazaei, 2012; Alessandra de Avila Souza et al., 2022; Gurunathan et al., 2022). Secondly, the low temperature inside the refrigerator slows down chemical reactions and the growth of microorganisms that can affect meat quality (Leygonie et al., 2012a; Kumar et al., 2015). This low temperature contributes to color preservation and prevents undesired changes. Lastly, the prevention of oxidation through citrus treatment is also a crucial factor. Citrus-derived antioxidants, whether in the form of extracts or raw juice, have proven effective in reducing oxidation damage to food items (Borah et al., 2014; Ben Hsouna et al., 2017; Martínez-Zamora et al., 2021; Borghi and Pavanelli, 2023). Ensuring that meat is stored in an airtight container or well-wrapped helps prevent the oxidation of fats and proteins, which can lead to color changes, as observed in some treatments utilizing citrus as a coating material (Alizadeh et al., 2019; Panahi et al., 2022; Venkatachalam et al., 2023). By considering these factors, chicken meat can maintain its quality and color even after storage.

The firmness of chicken meat treated with citrus shows an increase after being stored. This is in contrast to previous findings stating that coating chicken breast meat with a mixture of lemon peel extract can reduce the hardness value by -0.742 N (Alizadeh et al., 2019). While there might be a positive link between adding citrus additives and the hardness of chicken meat, other factors like dehydration during cold storage can decrease moisture and lead to changes in nutrient composition. These factors may contribute to an increase in the hardness of chicken meat (Lagerstedt et al., 2008; Leygonie et al., 2012b; Ab Aziz et al., 2020).

Clearly, one of the drawbacks of meat storage is the alteration of its nutrient composition; this meta-analysis reveals that only the protein component undergoes changes after storage. The alteration in the protein component of meat, despite its expected stability, poses a somewhat perplexing question. One potential explanation is the reduction in water content during storage. The loss of water due to evaporation during refrigerator storage has the potential to decrease the biomass of chicken meat (Leygonie et al., 2012a, 2012b), likely resulting in an increase in protein content. However, such structural damage can affect the texture and quality of the meat after thawing. Nevertheless, other nutrient compositions are not affected either by citrus treatment or storage.

Hedonic Test

Various characteristics play a role in determining the overall acceptability of a product, with taste being a crucial factor in food selection (Liem et al., 2011). Citrus-derived compounds, known for their natural antioxidant properties, play a significant role in extending the shelf life of food products. In the context of chicken meat, which contains various flavor components like seasonings and spices, the acceptability is influenced by these factors. Citrus, in this case, serves as a natural marinating agent and antioxidant in chicken meat, controlling gram-negative bacteria, enhancing texture and flavor, and contributing to preservation and spoilage reduction (Alahakoon et al., 2015). Panahi et al., (2022) reported comparable outcomes in the hedonic evaluation, indicating no significant differences among the observed parameters. The trend in sensory evaluation changes during storage aligns with oxidation variations in the tested treatments, likely attributable to fat oxidation. This process results in a decline in sensory quality and a reduction in nutrient content (Panahi et al., 2022). From this meta-analysis, it is evident that the color, odor, juiciness, and acceptability aspects of citrus-preserved chicken meat are superior to the control when stored in the refrigerator.

CONCLUSIONS

The detrimental effects on chicken meat during storage, indicated by elevated levels of aerobic bacteria, TBARS, and TVBN, are substantially mitigated by the citrus-derived additives. Citrus hystrix demonstrates a robust ability to reduce aerobic bacteria and TBARS. Temperature and storage duration have minimal impact on the nutritional quality of chicken meat. On the contrary, the hedonic quality of chicken meat improves significantly after storage when treated with citrus additives.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The article processing charge (APC) for the present work was fully covered by Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. The author expresses profound thanks to all members of Animal Feed and Nutrition Modeling (AFENUE) Research Group and Meta-Analysis in Plant Science (MAPS) Research Group, Indonesia, for providing technical support during the current work.

Ethical Clearance: The presented document is authentic and has not been previously published in any medium or language.

Author Contributions: Budiarto, R.: funding acquisition, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing. Ujilestari, T. and Sitaresmi, P. I.: conceptualization, supervision, and project administration. Wahyono, T. and Sholikin, M. M.: supervision, methodology, and validation. Widodo, S. and Wulandari: data curations, software, and formal analysis. Rumhayati, B.; Adli, D. N.; and Hudaya, M. F.: visualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing.

Authorization for Publication: All authors agreed on the content, and each granted explicit approval for submission.

Data Available Statement: The authors state that the details supporting the findings in this research can be obtained by making a reasonable request for the article.

DISCLOSURES

The author claims that no conflicts of interest or funding issues have occurred while preparing this meta-analysis manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ab Aziz M.F., Hayat M.N., Kaka U., Kamarulzaman N.H., Sazili A.Q. Physico-chemical characteristics and microbiological quality of broiler chicken pectoralis major muscle subjected to different storage temperature and duration. Foods. 2020;9:741. doi: 10.3390/foods9060741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi K.D., Olorunsanya O.A., Abe O.T. Effect of citrus seed extracts on oxidative stability of raw and cooked chicken meat. Iran. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2013;3:195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Adli D.N., Sadarman S., Irawan A., Jayanegara A., Wardiny T.M., Prihambodo T.R., Nayohan S., Permata D., Sholikin M.M., Yekti A.P.A. Effects of oligosaccharides on performance, egg quality, nutrient digestibility, antioxidant status, and immunity of laying hens: a meta-analysis. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2023;22:594–604. [Google Scholar]

- Alahakoon A.U., Bae Y.S., Kim H.J., Jung S., Jayasena D.D., Yong H.I., Kim S.H., Jo C. The effect of citrus and onion peel extracts, calcium lactate, and phosvitin on microbial quality of seasoned chicken breast meat. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2013;40:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Alahakoon A.U., Jayasena D.D., Jung S., Kim S.H., Kim H.J., Jo C. Effects of electron beam irradiation and high pressure treatment combined with citrus peel extract on seasoned chicken breast meat. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015;39:2332–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandra de Avila Souza M., Shimokomaki M., Nascimento Terra N., Petracci M. Oxidative changes in cooled and cooked pale, soft, exudative (PSE) chicken meat. Food Chem. 2022;385 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajo N. Tenderize chicken breast meat by using different methods of curing. Pakistan J. Nutr. 2009;8:1180–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh Z., Yousefi S., Ahari H. Optimization of bioactive preservative coatings of starch nanocrystal and ultrasonic extract of sour lemon peel on chicken fillets. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019;300:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saman M.A., Abdella A., Mazrou K.E., Tayel A.A., Irmak S. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of different extracts of the peel of kumquat (Citrus japonica Thunb) J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019;13:3221–3229. [Google Scholar]

- Amjadi S., Almasi H., Ghadertaj A., Mehryar L. Whey protein isolate-based films incorporated with nanoemulsions of orange peel (Citrus sinensis) essential oil: Preparation and characterization. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021;45 [Google Scholar]

- Anang D.M., Rusul G., Bakar J., Ling F.H. Effects of lactic acid and lauricidin on the survival of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enteritidis and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in chicken breast stored at 4°C. Food Control. 2007;18:961–969. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhit A.E.-D.A., Holman B.W.B., Giteru S.G., Hopkins D.L. Total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) and its role in meat spoilage: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:280–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Braïek O., Smaoui S. Chemistry, safety, and challenges of the use of organic acids and their derivative salts in meat preservation. J. Food Qual. 2021;2021:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hsouna A., Ben Halima N., Smaoui S., Hamdi N. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0487-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah A., Mahanta C.L., Devatkal S.K., Narsaiah K. Utilization of fruit by-product for the shelf life extension of chicken meat ball. J. Food Res. Technol. 2014;2:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Borghi S.M., Pavanelli W.R. Antioxidant compounds and health benefits of citrus fruits. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1526. doi: 10.3390/antiox12081526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiarto R., Sholikin M.M. Kaffir lime essential oil variation in the last fifty years: a meta-analysis of plant origins, plant parts and extraction methods. Horticulturae. 2022;8:1132. [Google Scholar]

- Budiarto R., Mubarok S., Nursuhud N., Rahmat B.P.N. Citrus is a multivitamin treasure trove: a review. J. Trop. Crop Sci. 2023;10:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Budiarto R., Poerwanto R., Santosa E., Efendi D., Agusta A. Preliminary study on antioxidant and antibacterial activity of kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix DC) leaf essential oil. Appl. Res. Sci. Technol. 2021;1:58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Carr A.C., Rowe S. The emerging role of vitamin C in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020;12:3286. doi: 10.3390/nu12113286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakoun, H., A. H. Alabdalall, I. Ababutain, R. Alyami, A. Debbabi, and T. Yangui. 2023. Effectiveness of Citrus lemon juice's waste essential oil and aqueous phase as a preservative against Salmonella enteritidis in chicken meat, 1–19. Preprint.

- Charmpi C., Van Reckem E., Sameli N., Van der Veken D., De Vuyst L., Leroy F. The use of less conventional meats or meat with high ph can lead to the growth of undesirable microorganisms during natural meat fermentation. Foods. 2020;9:1386. doi: 10.3390/foods9101386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhao J., Zhu L., Luo X., Mao Y., Hopkins D.L., Zhang Y., Dong P. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging on shelf life and bacterial community of roast duck meat. Food Res. Int. 2020;137 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouliara E., Karatapanis A., Savvaidis I.N., Kontominas M.G. Combined effect of oregano essential oil and modified atmosphere packaging on shelf-life extension of fresh chicken breast meat, stored at 4°C. Food Microbiol. 2007;24:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coma V. Bioactive packaging technologies for extended shelf life of meat-based products. Meat Sci. 2008;78:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie T.P.T., Lamb A.J. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;26:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denaro M., Smeriglio A., Xiao J., Cornara L., Burlando B., Trombetta D. New insights into citrus genus: from ancient fruits to new hybrids. Food Front. 2020;1:305–328. [Google Scholar]

- Denkova-Kostova R., Teneva D., Tomova T., Goranov B., Denkova Z., Shopska V., Slavchev A., Hristova-Ivanova Y. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from tangerine (Citrus reticulata L.), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi L.), lemon (Citrus lemon L.) and cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume) Zeitschrift Für Naturforsch. C. 2021;76:175–185. doi: 10.1515/znc-2020-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosoky N., Setzer W. Biological activities and safety of Citrus spp. Essential oils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1966. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espina L., Somolinos M., Lorán S., Conchello P., García D., Pagán R. Chemical composition of commercial citrus fruit essential oils and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity acting alone or in combined processes. Food Control. 2011;22:896–902. [Google Scholar]

- Fouladkhah A., Geornaras I., Nychas G., Sofos J.N. Antilisterial properties of marinades during refrigerated storage and microwave oven reheating against post-cooking inoculated chicken breast meat. J. Food Sci. 2013;78:285–289. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gęgotek A., Skrzydlewska E. Ascorbic acid as antioxidant. Vitam. Horm. 2023;121:247–270. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2022.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groppo M., Afonso L.F., Pirani J.R. A review of systematics studies in the Citrus family (Rutaceae, Sapindales), with emphasis on American groups. Brazilian J. Bot. 2022;45:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Huang J., Sun X., Lu Q., Huang M., Zhou G. Effect of normal and modified atmosphere packaging on shelf life of roast chicken meat. J. Food Saf. 2018;38:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gurunathan K., Tahseen A., Manyam S. Effect of aerobic and modified atmosphere packaging on quality characteristics of chicken leg meat at refrigerated storage. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höll L., Behr J., Vogel R.F. Identification and growth dynamics of meat spoilage microorganisms in modified atmosphere packaged poultry meat by MALDI-TOF MS. Food Microbiol. 2016;60:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran K., Saeed M., Randhawa M.A., Sharif H.R. Extraction and applications of grapefruit (Citrus paradise) peel oil against E. coli. Pakistan J. Nutr. 2013;12:534–537. [Google Scholar]

- Irokanulo E., Oluyomi B., Nwonuma C. Effect of citrus fruit (Citrus sinensis, Citrus limon and Citrus aurantifolia) rind essential oils on preservation of chicken meat artificially infected with bacteria. African J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2021;21:18950–18964. [Google Scholar]

- Jo C., Kang H.J., Lee M., Lee N.Y., Byun M.W. The antioxtoative potential of lyophilized citrus peel extract in different meat model systems during storage at 20°C. J. Muscle Foods. 2004;15:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Jouki M., Khazaei N. Lipid oxidation and color changes of fresh camel meat stored under different atmosphere packaging systems. J. Food Process. Technol. 2012;03:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Juneja V.K., Fan X., Peña-Ramos A., Diaz-Cinco M., Pacheco-Aguilar R. The effect of grapefruit extract and temperature abuse on growth of Clostridium perfringens from spore inocula in marinated, sous-vide chicken products. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2006;7:100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.T., Son H.K., Lee H.J., Choi J.S., Il Choi Y., Lee J.J. Effects of grapefruit seed extract on oxidative stability and quality properties of cured chicken breast. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2017;37:429–439. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2017.37.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J., Alahakoon A.U., Jayasena D.D., Khan M.I., Nam K.C., Jo C., Jung S. Effects of electron beam irradiation and high-pressure treatment with citrus peel extract on the microbiological, chemical and sensory qualities of marinated chicken breast meat. Korean J. Poult. Sci. 2015;42:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Klangpetch W., Phromsurin K., Hannarong K., Wichaphon J., Rungchang S. Antibacterial and antioxidant effects of tropical citrus peel extracts to improve the shelf life of raw chicken drumettes. Int. Food Res. J. 2016;23:700–707. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Y., Singh P., Tanwar V.K., Ponnusamy P., Singh P.K., Shukla P. Augmentation of quality attributes of chicken tikka prepared from spent hen meat with lemon juice and ginger extract marination. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015;45:606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerstedt Å., Enfält L., Johansson L., Lundström K. Effect of freezing on sensory quality, shear force and water loss in beef M. longissimus dorsi. Meat Sci. 2008;80:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latou E., Mexis S.F., Badeka A.V., Kontakos S., Kontominas M.G. Combined effect of chitosan and modified atmosphere packaging for shelf life extension of chicken breast fillets. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2014;55:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Leygonie C., Britz T.J., Hoffman L.C. Impact of freezing and thawing on the quality of meat: review. Meat Sci. 2012;91:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygonie C., Britz T.J., Hoffman L.C. Meat quality comparison between fresh and frozen/thawed ostrich M. iliofibularis. Meat Sci. 2012;91:364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem D.G., Miremadi F., Keast R. Reducing sodium in foods: the effect on flavor. Nutrients. 2011;3:694–711. doi: 10.3390/nu3060694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Li X., Zhao P., Zhang X., Qiao O., Huang L., Guo L., Gao W. A review of chemical constituents and health-promoting effects of citrus peels. Food Chem. 2021;365 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Zhao C., Shi H., Liao Y., Xu F., Du H., Xiao H., Zheng J. Nutrients and bioactives in citrus fruits: different citrus varieties, fruit parts, and growth stages. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023;63:2018–2041. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1969891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv X., Zhao S., Ning Z., Zeng H., Shu Y., Tao O., Xiao C., Lu C., Liu Y. Citrus fruits as a treasure trove of active natural metabolites that potentially provide benefits for human health. Chem. Cent. J. 2015;9:68. doi: 10.1186/s13065-015-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkowska-Lesiak M., Zdanowska-Sąsiadek Ż., Stelmasiak A., Damaziak K., Michalczuk M., Poławska E., Wyrwisz J., Wierzbicka A. Effect of packaging method and cold-storage time on chicken meat quality. CyTA - J. Food. 2016;14:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Martínez F., Sánchez-Meca J. Weighting by inverse variance or by sample size in random-effects meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010;70:56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Zamora L., Peñalver R., Ros G., Nieto G. Substitution of synthetic nitrates and antioxidants by spices, fruits and vegetables in clean label Spanish chorizo. Food Res. Int. 2021;139 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mexis S.F., Chouliara E., Kontominas M.G. Shelf life extension of ground chicken meat using an oxygen absorber and a citrus extract. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2012;49:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moura-Alves M., Esteves A., Ciríaco M., Silva J.A., Saraiva C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant edible films and coatings in the shelf-life improvement of chicken meat. Foods. 2023;12:2308. doi: 10.3390/foods12122308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeyemi O.A., Alegbeleye O.O., Strateva M., Stratev D. Understanding spoilage microbial community and spoilage mechanisms in foods of animal origin. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020;19:311–331. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padayatty S.J., Katz A., Wang Y., Eck P., Kwon O., Lee J.-H., Chen S., Corpe C., Dutta A., Dutta S.K., Levine M. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: Evaluation of its role in disease prevention. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2003;22:18–35. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., Moher D., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J.M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M.M., Li T., Loder E.W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., McGuinness L.A., Stewart L.A., Thomas J., Tricco A.C., Welch V.A., Whiting P., McKenzie J.E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panahi Z., Khoshbakht R., Javadi B., Firoozi E., Shahbazi N. The effect of sodium alginate coating containing citrus (Citrus aurantium) and lemon (Citrus lemon) extracts on quality properties of chicken meat. J. Food Qual. 2022;2022 [Google Scholar]

- Panthong K., Srisud Y., Rukachaisirikul V., Hutadilok-Towatana N., Voravuthikunchai S.P., Tewtrakul S. Benzene, coumarin and quinolinone derivatives from roots of Citrus hystrix. Phytochemistry. 2013;88:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhiz H., Roohbakhsh A., Soltani F., Rezaee R., Iranshahi M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of the citrus flavonoids hesperidin and hesperetin: An updated review of their molecular mechanisms and experimental models. Phyther. Res. 2015;29:323–331. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil B.S., Jayaprakasha G.K., Murthy K.N.C. Beyond vitamin C: the diverse, complex health-promoting properties of citrus fruits. Citrus Res. Technol. 2017;38:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Jiménez-Belenguer A., Settanni L., Perdones A., Moschetti M., Palazzolo E., Guarrasi V., Vargas M., Germanà M.A., Moschetti G. Antilisterial effect of citrus essential oils and their performance in edible film formulations. Food Control. 2016;59:750–758. [Google Scholar]

- Ratanachamnong P., Chunchaowarit Y., Namchaiw P., Niwaspragrit C., Rattanacheeworn P., Jaisin Y. HPLC analysis and in vitro antioxidant mediated through cell migration effect of Citrus hystrix water extract on human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Heliyon. 2023;9:e13068. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimini S., Petracci M., Smith D.P. The use of thyme and orange essential oils blend to improve quality traits of marinated chicken meat. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:2096–2102. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M., Durani A.I., Asari A., Ahmed M., Ahmad M., Yousaf N., Muddassar M. Investigation of antioxidant and antibacterial effects of citrus fruits peels extracts using different extracting agents: phytochemical analysis with in silico studies. Heliyon. 2023;9:e15433. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol K.H., Joo B.J., Kim H.W., Chang O.K., Ham J.S., Oh M.H., Park B.Y., Lee M. Effect of medicinal plant extract incorporated carrageenan based films on shelf-life of chicken breast meat. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2013;33:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shao L., Chen S., Wang H., Zhang J., Xu X., Wang H. Advances in understanding the predominance, phenotypes, and mechanisms of bacteria related to meat spoilage. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;118:822–832. [Google Scholar]

- Sreepian P.M., Rattanasinganchan P., Sreepian A. Antibacterial efficacy of Citrus hystrix (makrut lime) essential oil against clinical multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023;31:1094–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2023.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagos D. Antioxidant activity of polyphenolic plant extracts. Antioxidants. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., Ieamkheng S., Noonim P., Lekjing S. Effect of edible coating made from arrowroot flour and kaffir lime leaf essential oil on the quality changes of pork sausage under prolonged refrigerated storage. Foods. 2023;12:3691. doi: 10.3390/foods12193691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waikedre J., Dugay A., Barrachina I., Herrenknecht C., Cabalion P., Fournet A. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils from new caledonian Citrus macroptera and Citrus hystrix. Chem. Biodivers. 2010;7:871–877. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B.C., Dahabreh I.J., Trikalinos T.A., Lau J., Trow P., Schmid C.H. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. J. Stat. Softw. 2012;49:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B.C., Lajeunesse M.J., Dietz G., Dahabreh I.J., Trikalinos T.A., Schmid C.H., Gurevitch J. Open MEE: Intuitive, open-source software for meta-analysis in ecology and evolutionary biology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017;8:941–947. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Li M., Ma F., Wang H., Xu X., Zhou G. Physicochemical properties of Pseudomonas fragi isolates response to modified atmosphere packaging. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017;364:1–8. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., li Q., Tang W., Ma F., Wang H., Xu X., Qiu W. AprD is important for extracellular proteolytic activity, physicochemical properties and spoilage potential in meat-borne Pseudomonas fragi. Food Control. 2021;124 [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.A., Terol J., Ibanez V., López-García A., Pérez-Román E., Borredá C., Domingo C., Tadeo F.R., Carbonell-Caballero J., Alonso R., Curk F., Du D., Ollitrault P., Roose M.L., Dopazo J., Gmitter F.G., Rokhsar D.S., Talon M. Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus. Nature. 2018;554:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nature25447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Wang Y., Nian M., Lv H., Chen J., Qiao H., Yang X., Li X., Chen X., Zheng X., Wu S. Citrus hystrix: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacology and industrial applications research progress. Arab. J. Chem. 2023;16 [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z., Xi W., Hu Y., Nie C., Zhou Z. Antioxidant activity of citrus fruits. Food Chem. 2016;196:885–896. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]