Abstract

This study compares outcomes of surgery and functional bracing for closed humeral shaft fractures after 5 years of follow-up.

A randomized clinical trial (the Finnish Shaft of the Humerus [FISH] trial1) compared outcomes of surgery and functional bracing in the treatment of closed humeral shaft fractures. The trial found no clinically meaningful differences at 12 months. However, 14 of 44 patients allocated to functional bracing (32%) required secondary surgery, with outcomes inferior to those of initial surgery and successful bracing at 1- and 2-year follow-up.1,2 Here, we report the 5-year outcomes of the FISH trial.

Methods

This was a prespecified 5-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial.1,3 The protocol (Supplement 1) was approved by the institutional review board of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District. Patients gave written informed consent. At entry, 82 adult patients with a closed humeral shaft fracture were randomized 1:1 to either surgery or functional bracing in 2 university hospitals in Finland. The groups had similar baseline characteristics.1 The 5-year follow-up was carried out between November 2017 and January 2023.

We used the same outcomes as in the original publication.1 The primary outcome was the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) score (range, 0-100; 0 denotes no disability and 100 extreme disability; minimal clinically important difference [MCID], 10 points). The secondary outcomes are listed in the Table. Outcomes were assessed by a physiotherapist unaware of the group allocations. Adverse events (complications, hardware removals) were assessed.

Table. Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 5 Years.

| Outcome | Mean (95% CI) | Between-group mean difference (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery group (n = 38) | Bracing group (n = 44) | |||

| Primary outcome: DASH scorea | 8.6 (3.7 to 13.4) | 8.4 (4.1 to 12.6) | 0.2 (−6.3 to 6.7) | .95 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Painb | ||||

| At rest | 0.93 (0.34 to 1.52) | 0.55 (0.02 to 1.08) | 0.38 (−0.40 to 1.16) | .34 |

| During activities | 2.04 (1.18 to 2.90) | 1.35 (0.58 to 2.12) | 0.69 (−0.48 to 1.84) | .25 |

| Constant-Murley scorec | 80.8 (74.7 to 86.9) | 78.7 (73.1 to 84.2) | 2.1 (−6.2 to 10.3) | .62 |

| Elbow ROM, degreesd | 145 (139 to 150) | 137 (131 to 142) | 8 (0 to 16) | .04 |

| 15D scoree | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.93) | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.92) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05) | .62 |

| DASH work module scoref | 6.4 (0 to 15.6) | 3.1 (0 to 12.1) | 3.3 (−9.7 to 16.2) | .62 |

| DASH sports/performing arts module scoref | 3.1 (0 to 14.3) | 14.3 (0.7 to 27.8) | −11.2 (−28.9 to 6.6) | .22 |

| Patients with acceptable symptomatic state, %g | 83 (65 to 94) | 84 (69 to 94) | −1 (−18 to 17) | >.99 |

| Adequate clinical recovery, %h | 86 (68 to 96) | 92 (79 to 98) | −6 (−21 to 9) | .46 |

| Satisfaction with shoulder functioni | 8.8 (8.0 to 9.6) | 8.5 (7.8 to 9.2) | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.3) | .60 |

| Satisfaction with elbow functioni | 8.9 (8.2 to 9.6) | 9.2 (8.6 to 9.8) | −0.3 (−1.2 to 0.6) | .52 |

| Satisfaction with upper extremity functioni | 8.8 (8.0 to 9.6) | 8.4 (7.6 to 9.1) | 0.4 (−0.6 to 1.5) | .41 |

| Patients willing to repeat the same treatment, %j | 93 (77 to 99) | 76 (60 to 89) | 17 (0 to 33) | .10 |

Abbreviations: 15D, 15-dimensional instrument; DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand; ROM, range of motion.

Validated 30-item tool assessing upper-extremity symptoms in daily life (range, 0 [no disability] to 100 [extreme disability]). Values lower than 10 represent a mean value in a randomly selected population aged 20 to 60 years, and a score of 10 is generally regarded as the minimal clinically important difference.

Reported on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst imaginable pain.

Assesses various conditions affecting shoulder function with 2 subjective (pain, 0-15 points; activities of daily living, 0-20 points) and 2 objective (shoulder range of motion, 0-40 points; strength, 0-25 points) subscales. The range is 0 to 100, with higher score denoting better function. Values around 85 are considered normal in individuals aged 40 to 60 years. Measurements were performed by a physiotherapist unaware of the treatment group.

Measured by a physiotherapist using a goniometer and calculated using the difference in degrees between full flexion and full extension. A difference of more than 14 degrees is considered clinically important.

Generic health-related quality-of-life instrument (range, 1 [full health] to 0 [death]). Values higher than 0.9 are comparable with a randomly selected Finnish population aged 30 years or older.

Comprises 4 questions assessing the effect on work, sports, or performing arts (range, 0 [none] to 100 [extreme disability]). A score of 10 points or lower indicates minimal limitations on performance at most.

Acceptable symptomatic state was determined using patient’s global assessment of satisfaction regarding the injured arm by asking, “How satisfied are you with the overall condition of your injured upper limb and its effect on your daily life?” Responses were given on a 7-point Likert scale. “Very satisfied” and “satisfied” were categorized as having an acceptable symptomatic state and “somewhat satisfied,” “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied,” and “very dissatisfied” as not having an acceptable symptomatic state.

A DASH score within a minimal important difference (10 points) of the preinjury score was considered to indicate adequate clinical recovery.

Reported on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale, where 0 is the worst and 10 is the best condition.

Patients were asked whether they would like to have the same treatment again if they sustained a similar kind of injury later. Responses were given as “yes” or “no.”

We carried out both intention-to-treat (ITT; primary) and per-protocol (PP; secondary) analyses. In the PP analysis, patients requiring secondary surgery after failed bracing were included as a third group.2 Between-group comparisons were performed using a mixed-model repeated-measures analysis of variance assuming missingness at random. Study group, time of assessment, and study site were included as fixed factors and patients as random factors. The treatment effect was quantified as the difference in DASH score (mean and 95% CI) between the groups at 5 years. For categorical variables, we used the Fisher exact test. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05 with 2-sided testing. Data were analyzed using Stata, version 15.1.

Results

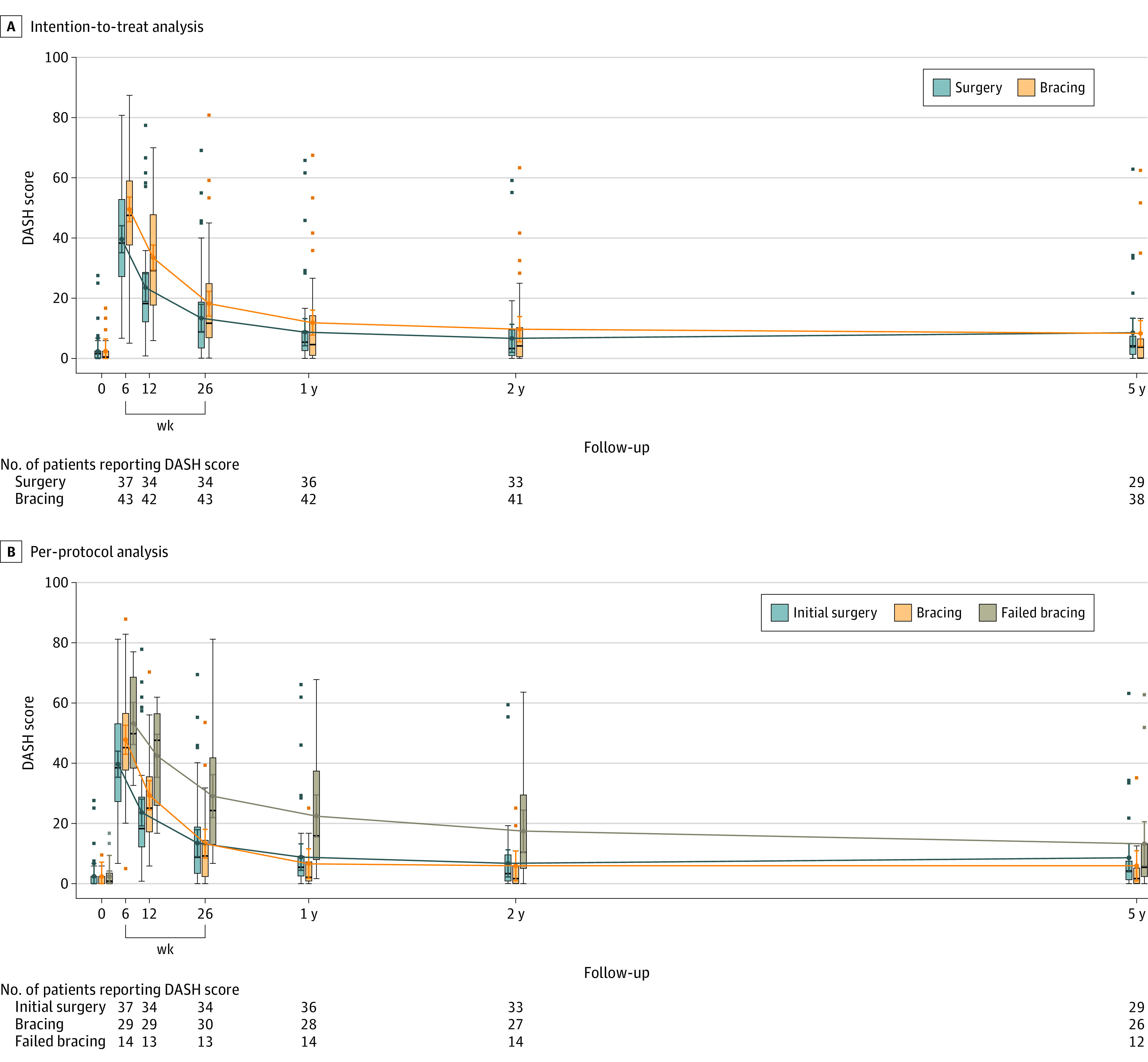

Of the 82 randomized patients, 67 (82%; mean [SD] age, 52 [16] years; 39 [58%] men) completed the 5-year follow-up: 29 of 38 in the surgery group (76%) and 38 of 44 in the bracing group (86%). In the ITT analysis, the mean DASH score was 8.6 (95% CI, 3.7-13.4) in the surgery group and 8.4 (95% CI, 4.1-12.6) in the bracing group (difference, 0.2 [95% CI, −6.3 to 6.7]) (Figure and Table). All secondary outcomes showed no significant differences except for elbow range of motion (Table).

Figure. Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) Score Over Time.

A, Results of the intention-to-treat analysis, with groups presented as randomized. B, Results of the per-protocol analysis, with groups receiving initial surgery, successful bracing, and secondary surgery after failed bracing presented separately. A and B, The DASH score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 100 (extreme disability). Time 0 indicates before fracture. Colored error bars indicate 95% CIs of the point estimates of group means; boxes, 25th and 75th percentiles of observed values; horizontal lines within boxes, median DASH scores; black error bars, highest and lowest values within 1.5 times the IQR; and data points beyond the error bars, individual values outside this range.

The PP analysis confirmed the findings of the ITT analysis, showing no significant differences among the initial surgery, the successful bracing, and the secondary surgery after failed bracing groups. The corresponding mean DASH scores were 8.6 (95% CI, 4.0-13.3), 6.0 (95% CI, 1.0-11.0), and 13.3 (95% CI, 5.9-20.6), respectively, yielding the following between-group differences: initial surgery vs successful bracing, 2.7 (95% CI, −4.2 to 9.5); initial surgery vs failed bracing, −4.7 (95% CI, −13.3 to 4.0); and successful bracing vs failed bracing, −7.3 (95% CI, −16.2 to 1.6).

There were no late complications. No hardware removals were required.

Discussion

This 5-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial comparing surgery and functional bracing for closed humeral shaft fractures showed comparable and satisfactory outcomes irrespective of the initial treatment strategy. Although 32% of the patients allocated to functional bracing required secondary surgery and had inferior results at 1- and 2-year follow-up,1,2 there were no clinically relevant differences at 5 years. However, as the MCID for DASH falls within the 95% CIs of the comparisons between failed bracing and the other 2 groups, a potential meaningful effect cannot be entirely ruled out. The study was limited by 18% loss to follow-up. These findings offer clinicians and patients valuable insight into the probable trajectory of recovery and, thus, facilitate shared decision-making regarding the optimal treatment strategy for each patient with a closed humeral shaft fracture.

Section Editors: Kristin Walter, MD, and Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editors; Karen Lasser, MD, Senior Editor.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Rämö L, Sumrein BO, Lepola V, et al. ; FISH Investigators . Effect of surgery vs functional bracing on functional outcome among patients with closed displaced humeral shaft fractures: the FISH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1792-1801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rämö L, Paavola M, Sumrein BO, et al. ; FISH Investigators . Outcomes with surgery vs functional bracing for patients with closed, displaced humeral shaft fractures and the need for secondary surgery: a prespecified secondary analysis of the FISH randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):1-9. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rämö L, Taimela S, Lepola V, Malmivaara A, Lähdeoja T, Paavola M. Open reduction and internal fixation of humeral shaft fractures versus conservative treatment with a functional brace: a study protocol of a randomised controlled trial embedded in a cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e014076. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement