Key Points

Question

Is silver diamine fluoride noninferior to dental sealants and atraumatic restorations in the prevalence of dental caries when used in schools?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 7418 children, the incidence of dental caries was comparable between children treated with silver diamine fluoride and those treated with dental sealants and atraumatic restorations. For caries prevalence, silver diamine fluoride was noninferior in adjusted models.

Meaning

The findings suggest that silver diamine fluoride can be effectively used as a primary intervention for school-based caries prevention.

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the use of silver diamine fluoride for reducing the prevalence of dental caries.

Abstract

Importance

Dental caries is the world’s most prevalent noncommunicable disease and a source of health inequity; school dental sealant programs are a common preventive measure. Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) may provide an alternative therapy to prevent and control caries if shown to be noninferior to sealant treatment.

Objective

To determine whether school-based application of SDF is noninferior to dental sealants and atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) in the prevalence of dental caries.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Silver Diamine Fluoride Versus Therapeutic Sealants for the Arrest and Prevention of Dental Caries in Low-Income Minority Children (CariedAway) study was a pragmatic noninferiority cluster-randomized clinical trial conducted from February 2018 to June 2023 to compare silver diamine fluoride vs therapeutic sealants for the arrest and prevention of dental caries. Children at primary schools in New York, New York, with at least 50% of the student population reporting as Black or Hispanic and at least 80% receiving free or reduced lunch were included. This population was selected as they are at the highest risk of caries in New York. Students were randomized to receive either SDF or sealant with ART; those aged 5 to 13 years were included in the analysis. Treatment was provided at every visit based on need, and the number of visits varied by child. Schools with preexisting oral health programs were excluded, as were children who did not speak English. Of 17 741 students assessed for eligibility, 7418 were randomized, and 4100 completed follow-up and were included in the final analysis.

Interventions

Participants were randomized at the school level to receive either a 38% concentration SDF solution or glass ionomer sealants and ART. Each participant also received fluoride varnish.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary study outcomes were the prevalence and incidence of dental caries.

Results

A total of 7418 children (mean [SD] age, 7.58 [1.90] years; 4006 [54.0%] female; 125 [1.7%] Asian, 1246 [16.8%] Black, 3648 [49.2%] Hispanic, 153 [2.1%] White, 114 [1.5%] multiple races or ethnicities, 90 [1.2%] other [unspecified], 2042 [27.5%] unreported) were enrolled and randomized to receive either SDF (n = 3739) or sealants with ART (n = 3679). After initial treatment, 4100 participants (55.0%) completed at least 1 follow-up observation. The overall baseline prevalence of dental caries was approximately 27.2% (95% CI, 25.7-28.6). The odds of decay prevalence decreased longitudinally (odds ratio [OR], 0.79; 95% CI, 0.75-0.83) and SDF was noninferior compared to sealants and ART (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.80-1.11). The crude incidence of dental caries in children treated with SDF was 10.2 per 1000 tooth-years vs 9.8 per 1000 tooth-years in children treated with sealants and ART (rate ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.97-1.12).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this school-based pragmatic randomized clinical trial, application of SDF resulted in nearly identical caries incidence compared to dental sealants and ART and was noninferior in the longitudinal prevalence of caries. These findings suggest that SDF may provide an effective alternative for use in school caries prevention.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03442309

Introduction

Dental caries is the world’s most prevalent noncommunicable disease.1 The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research2 estimates that more than 50% of US children between the ages of 6 and 8 years have experienced caries, with the rate in some racial and ethnic minority groups exceeding 70%. The United Nations considers oral diseases to be a major global burden that shares common risk factors with other noncommunicable diseases, and the World Health Organization Global Oral Health Action Plan3 names oral disease prevention as a primary strategic objective, recommending the use of cost-effective, community-based methods to prevent caries. In 2022, the World Health Organization added glass ionomer sealants and silver diamine fluoride (SDF) to its Model List of Essential Medicines.4

Despite increases in Medicaid entitlements for dental benefits, there remain persistent access challenges to oral disease prevention throughout the US. More than 69 million individuals in the US live in dental care health professional shortage areas.5 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention6 recommends school sealant programs to increase access to care and improve health equity. Dental sealants—thin coatings applied to the pits and fissures of teeth to protect against bacteria—can prevent the onset of carious lesions and arrests them in the early stages.7,8 However, the burgeoning costs of care limits their use in schools.9 Alternatively, SDF is a colorless alkaline solution consisting of silver and fluoride with antimicrobial properties that remineralizes teeth. In clinical studies, SDF application prevents caries in the primary dentition compared to placebo10 and arrests existing caries.11 SDF can be applied in minutes12 and is a cost-effective strategy to reduce the burden of caries, particularly in under resourced areas.13 In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration14 granted breakthrough therapy status to SDF.

The Silver Diamine Fluoride Versus Therapeutic Sealants for the Arrest and Prevention of Dental Caries in Low-Income Minority Children (CariedAway) pragmatic15 randomized clinical trial16 investigated the use of SDF as an alternative therapy for community-based caries control and prevention. Primary clinical outcomes for CariedAway included the noninferiority of SDF compared to dental sealants and atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) in the 2-year arrest of existing dental caries17 and the 4-year prevalence of caries. We report on the cumulative incidence and prevalence of caries over 4 years.

Methods

Design and Participants

CariedAway was a longitudinal noninferiority pragmatic cluster-randomized clinical trial16 conducted from February 1, 2019, to June 1, 2023. The trial was approved by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03442309), and is reported following the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) reporting guideline. The trial protocol is Supplement 1.

Any school in the New York, New York, metropolitan area with a total student population consisting of at least 50% Black or Hispanic students and with at least 80% of students receiving free or reduced lunch was eligible for inclusion. This population was selected as they are at the highest risk of caries in New York City. For enrolled schools, any child with parental written informed consent and participant assent was enrolled. While any child meeting these criteria was enrolled, inclusion into analysis was restricted to those aged 5 to 13 years. Additional exclusion criteria were if the school had a preexisting oral health program or if the child did not speak English.

Interventions and Procedures

Our primary experimental condition consisted of a 38% SDF solution (2.24 F-ion mg/dose). The active control consisted of glass ionomer cement sealants and atraumatic restorations, a minimally invasive approach that consists of preventive and restorative components to halt the progression of caries.18,19 Each participant also received a 5% sodium fluoride application.

For the experimental treatment, petroleum jelly was first applied to the lips and surrounding skin to prevent temporary staining that can result from direct contact of SDF with the soft tissue. Isolation was achieved by placing gauze and cotton rolls between the teeth to be treated and the tongue and cheek. One to 2 drops of SDF were dispensed into a mixing well and applied using a microapplicator to all posterior asymptomatic cavitated lesions as well as pits and fissures of premolars and molars. The material was agitated on the surface of all cavities using a scrubbing motion for a minimum of 30 seconds, followed by 60 seconds of air-drying time. One unit dose of fluoride varnish was then applied to all teeth to mask the taste of the SDF. The procedure was then repeated every 6 months per protocol with the exception of the disruption in study activities due to COVID-19.

For the active control, cavity conditioner was first applied to pits and fissures for 10 seconds. Sealant capsules were mixed for 10 seconds at 4000 rpm and then applied directly via the finger-sweep technique to all pits and fissures of bicuspids and molars, ensuring that closed margins were achieved. Atraumatic restorations were also placed on asymptomatic cavitated lesions, and fluoride varnish was applied to all teeth. At successive observations, sealants were reapplied to any unsealed or partially sealed bicuspids and molars. All treatments in both groups were provided in a dedicated room in each school using mobile equipment. Treatments in both groups were continued as long as the child was enrolled in the study.

Examiners

Treatments in the experimental group were provided by either dental hygienists or registered nurses, and by dental hygienists in the active control. All dental hygienists and registered nurses received identical training prior to the start of the academic year. Training consisted of didactic and experiential activities including screening, treatment protocol standardization exercises, and mock patient interactions.

Data Collection and Outcomes

Primary outcomes were the prevalence and incidence of dental caries. Caries diagnosis was determined through a full visual-tactile oral examination following the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) adapted criteria for epidemiology and clinical research settings.20 Each tooth surface was assessed as being either intact/sound, sealed, restored, decayed, or arrested. Screening criteria considered lesions scored as a 5 (distinct cavity with visible dentin) or 6 (extensive, more than half the surface, distinct cavity with visible dentin) on the ICDAS scale as decay. Any clinical presentation of a filling (eg, amalgam, composite, or stainless steel crown) on a tooth that previously was recorded as sound was analyzed as decay, as it indicated disease incidence occurring between observations.

Demographic data, including sex, race, and ethnicity, were obtained prior to treatment for future analyses. Race and ethnicity data were collected via self-report to support future assessment of effects within sociodemographic groups. Categories were derived from the New York City Department of Education. Participants selecting “other” race or ethnicity included all those not included in specific categories.

Randomization and Blinding

Schools were block-randomized to either the experimental or active control arm using a random number generator performed by one of us (R. R. R.) and verified by another (T. B. G.). Due to the staining effect of SDF, patients would be able to derive their groups. Clinicians were not blinded as the procedures differed for each treatment; however, they were not able to discern who treated each participant at prior study observations.

Impact of COVID-19

Data in CariedAway were collected biannually. However, due to the impact of COVID-19, schools in New York City were closed to health care professionals from March 2020 through September 2021. The time elapsed between observations corresponding to this period was approximately 2 years.

Power

Sample size calculations for the longitudinal prevalence of caries were previously reported16 assuming a power of 0.80, error rate of 5%, a repeated measures correlation of 0.5, and a per-visit attrition rate of 20%. Estimates also assumed a minimally detectable effect size of 0.25 and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.10, yielding a sample size of 12 874. However the observed intraclass correlation coefficient, computed using intercept-only mixed effects models, ranged from 0.013 (prevalence) to 0.015 (incidence). Thus, the final participant enrollment was sufficient for power requirements.

Statistical Analysis

At each observation, the proportion of participants in treatment groups with new caries or fillings was determined and bootstrapped confidence intervals for the difference were computed, accounting for any clustering effect of schools. We assessed longitudinal noninferiority using mixed-effects logistic regression models, where the outcome was the presence or absence of any new caries at each observation. Models included random intercepts for individual participants and school. Our noninferiority margin (0.10) was previously selected based on historical evidence and clinical judgement as to what would be an acceptable difference in efficacy for the prevention of dental caries.21,22 We converted the margin to the odds ratio (OR) scale by taking the average of the success proportion in the active control arm and determining the equivalent margin (OR δ, 0.63).23 We tested noninferiority at any observation by including an interaction between treatment and time, followed by a model with no interaction to assess noninferiority marginally. Comparisons to the OR δ were made using a (1 − 2α) confidence interval for the effect of treatment.24

We calculated the incidence rate for the total number of individual teeth that developed caries (in tooth-years) and derived the rate ratio as the most efficient estimator due to the small degree of intracluster correlation in responses.25 We then modeled the per-person number of caries present at each observation using multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial regression. Prespecified subgroup analyses for the effect of treatment over time and by the presence or absence of caries at baseline were performed.

We also conducted a series of supplementary analyses. To account for censored observations, we analyzed caries incidence using Cox proportional hazards regression with nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation.26 We then assessed whether treatment by either a dental hygienist or registered nurse affected caries prevalence in the experimental group. Finally, we restricted the primary analysis to only those participants who were enrolled and received their first examination and treatment in the 6 months prior to school shutdowns due to COVID-19 to ensure that all analyzed participants had the same elapsed time between observations. Statistical significance was determined at P < .05. Analysis was conducted in Stata version 18 (StataCorp) and R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation).

Results

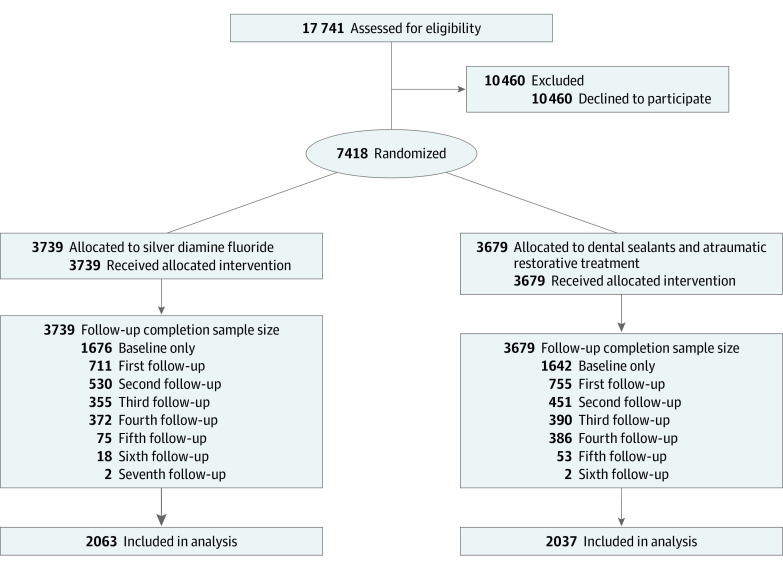

A total of 7418 participants were enrolled across 48 schools (mean [SD] age, 7.58 [1.90] years; 4006 [54.0%] female; 125 [1.7%] Asian, 1246 [16.8%] Black, 3648 [49.2%] Hispanic, 153 [2.1%] White, 114 [1.5%] multiple races or ethnicities, 90 [1.2%] other [unspecified], 2042 [27.5%] unreported) (Figure; Table 1). After randomization, there were 3739 participants (50.4%) in the experimental group (SDF) and 3679 (49.6%) in the active control group (sealant and ART). There were 4100 participants (55.5%) who completed at least 1 follow-up observation: 2063 (50.32%) in the experimental group and 2037 (49.68%) in the active control. The mean (SD) study observation time was 3.7 (0.32) years. The overall prevalence of baseline untreated caries was 26.7%, or 27.2% (95% CI, 25.7-28.6) for the experimental group and 26.2% (95% CI, 24.8-27.6) for the active control group. Within the SDF arm, 764 of 3735 baseline participants (20.5%) and 1154 of 8509 individual participant encounters (13.5%) were treated by registered nurses.

Figure. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

The average time elapsed between observations across all participants was as follows. First follow-up, 507 days; second, 300 days; third, 195 days; fourth, 169 days; fifth, 171 days; sixth, 170 days; seventh: 159 days. Any study dropout was considered and logged as lost to follow-up. No other reasons were documented, as the child most likely left the school.

Table 1. Sample Demographic Characteristics Overall and by Treatment.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Experimentala | Active controlb | |

| Enrolled participants | 7418 (100.0) | 3739 (50.4) | 3679 (49.6) |

| Baseline decay | 1980 (26.7) | 1016 (27.2) | 964 (26.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 4006 (54.0) | 1954 (52.3) | 2052 (55.8) |

| Male | 3412 (46.0) | 1785 (47.7) | 1627 (44.2) |

| Race and ethnicityc | |||

| Asian | 125 (1.7) | 88 (2.4) | 37 (1.0) |

| Black | 1246 (16.8) | 650 (17.4) | 596 (16.2) |

| Hispanic | 3648 (49.2) | 1766 (47.2) | 1882 (51.2) |

| White | 153 (2.1) | 86 (2.3) | 67 (1.8) |

| Multiple | 114 (1.5) | 67 (1.8) | 47 (1.3) |

| Otherd | 90 (1.2) | 56 (1.5) | 34 (0.9) |

| Unreported | 2042 (27.5) | 1026 (27.4) | 1016 (27.6) |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 7.6 (1.9) | 7.5 (1.9) | 7.6 (1.9) |

| Retained participants | 4100 (100.0) | 2063 (50.3) | 2037 (49.7) |

| Baseline decay | 1140 (27.8) | 584 (28.3) | 556 (27.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2228 (54.3) | 1088 (52.7) | 1140 (56.0) |

| Male | 1872 (45.7) | 975 (47.3) | 897 (44.0) |

| Race and ethnicityc | |||

| Asian | 78 (1.9) | 59 (2.9) | 19 (0.9) |

| Black | 794 (19.5) | 416 (20.2) | 378 (18.6) |

| Hispanic | 2329 (57.1) | 1155 (56.0) | 1174 (57.6) |

| White | 86 (2.1) | 56 (2.7) | 30 (1.5) |

| Multiple | 62 (1.5) | 40 (1.9) | 22 (1.1) |

| Otherd | 69 (1.7) | 41 (2.0) | 28 (1.4) |

| Unreported | 682 (16.6) | 296 (14.4) | 386 (19.0) |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 6.9 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.6) |

Experimental refers to treatment with silver diamine fluoride.

Active control refers to dental sealant and atraumatic restorative treatment.

Race and ethnicity data were collected via self-report using categories derived from the New York City Department of Education to support future assessment of effects within sociodemographic groups.

Unspecified.

The prevalence of participants with no new caries or fillings at each observation (Table 2) was similar in both groups, with differences in prevalence ranging from −0.001 to 0.031 across study observations. Bootstrapped confidence intervals were below the noninferiority margin. For mixed-model analyses of caries prevalence over time (Table 3), the interaction effect between time and treatment was not significant, indicating that noninferiority should be assessed marginally. Across both groups, the odds of untreated decay significantly decreased by approximately 21% at each observational visit (OR, 0.79, 95% CI, 0.75-0.83). Comparing the active control to the experimental treatment after adjusting for confounders, the OR was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.80-1.11; 90% CI, 0.82-1.08). The confidence interval for the marginal effect was outside the estimated OR δ.

Table 2. Prevalence of Participants Without New Caries or New Fillings at Each Observationa.

| Observation | Duration, db | Prevalence | Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active controlc | Experimentald | |||

| 2nd | 507 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.03 (−0.00 to 0.07) |

| 3rd | 300 | 0.69 | 0.69 | −0.00 (−0.04 to 0.04) |

| 4th | 195 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.00 (−0.05 to 0.05) |

| 5th | 169 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.06) |

Any single instance of decay or new fillings not previously observed was considered treatment failure.

Duration was days between observations.

Active control refers to dental sealant and atraumatic restorative treatment.

Experimental refers to treatment with silver diamine fluoride.

Table 3. Longitudinal Caries Prevalence and Effect of Sealants and Atraumatic Restorative Treatment Compared With Silver Diamine Fluoride for Untreated Decay on Any Dentition.

| Variable | Odds ratio (SE) | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational period | 0.79 (0.02) | 0.75-0.83 | <.001 |

| Active control vs experimentala | 0.94 (0.08) | 0.80-1.11 | .47 |

| Baseline decay | 82.75 (9.72) | 65.74-104.17 | <.001 |

| Previous care | 0.76 (0.12) | 0.56-1.02 | .07 |

| Sex, males | 1.06 (0.09) | 0.90-1.26 | .47 |

| Race and ethnicityb | |||

| Asian | 0.80 (0.24) | 0.44-1.45 | .47 |

| Black | 1.06 (0.12) | 0.84-1.31 | .61 |

| White | 0.66 (0.19) | 0.37-1.15 | .14 |

| Multiple | 0.87 (0.33) | 0.42-1.81 | .71 |

| Otherc | 2.10 (0.64) | 1.16-3.81 | .01 |

| Unreported | 0.96 (0.12) | 0.76-1.22 | .75 |

Active control refers to dental sealant and atraumatic restorative treatment and experimental to treatment with silver diamine fluoride.

Race and ethnicity data were collected via self-report using categories derived from the New York City Department of Education to support future assessment of effects within sociodemographic groups.

Unspecified.

For newly observed caries across the full study duration (Table 4), the crude incidence rate in the experimental group was 10.2 caries per 1000 tooth-years. The rate in the active control was 9.8 caries per 1000 tooth-years, for a rate ratio of 1.05 (95% CI, 0.97-1.12) and a preventive fraction of 0.023. From adjusted models for longitudinal caries incidence (eTable 1 in Supplement 2), the overall risk rate over time reduced (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.83; 95% CI, 0.81-0.85) with each observation. The risk comparing participants in the dental sealants with ART group to those in the SDF group was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.83-1.04). There were no significant interactions between treatment and time and treatment and baseline decay status.

Table 4. Incidence Rate of Dental Caries for Experimental and Active Controla.

| Variable | Experimentalb | Active controlc | Total | Incidence rate difference (95% CI) | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caries, No. | 1625 | 1433 | 3058 | 0.000 (−0.000 to 0.001) | 1.046 (0.973 to 1.123) |

| Tooth-years, No. | 157 979 | 145 653 | 303 632 | ||

| Incidence rate | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 |

Each condition also received fluoride varnish.

Experimental refers to treatment with silver diamine fluoride.

Active control refers to dental sealant and atraumatic restorative treatment.

In supplementary analyses, the hazard ratio comparing the active control to experimental for time to first observed carious lesion was 0.91 (95% CI, −0.823 to 1.08). There were no significant differences in caries prevalence in children treated with SDF by registered nurses compared to dental hygienists (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.67-1.19). For the restricted subsample, 4718 CariedAway participants were enrolled and treated in the 6 months prior to school closures due to COVID-19, 2998 of whom were viable for follow-up after pandemic restrictions were lifted (eFigure in Supplement 2). At the completion of the trial, follow-up data were obtained for 1831 participants (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Results for longitudinal analyses for caries prevalence (eTable 3 in Supplement 2) and incidence (eTable 4 in Supplement 2) were similar to that of full-sample analyses.

Discussion

School sealant programs have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the risk of dental caries,27 yet are underused due to the burdensome costs of care.9 Many children subsequently continue to live with untreated disease, which can lead to systemic infection and negatively affect child development.28 In this randomized clinical trial of primary school-aged children, application of SDF with fluoride varnish was noninferior compared to dental sealants, fluoride varnish, and ART in the longitudinal prevalence of caries when used in a school program. We conclude that SDF is an effective alternative for community-based prevention that may help address these existing barriers.

Although SDF is primarily used as a caries-arresting agent, it is also effective in the prevention of new caries.29,30 There is a reduced risk of new caries on surrounding sound dentition when existing lesions are treated,31 and SDF is more effective than fluoride varnish in preventing new caries in early childhood.32 However, prior short-term comparative assessments of SDF have yielded conflicting results on its superiority relative to glass ionomer sealants and atraumatic restorations.33,34 These previous trials were also restricted to either 12 or 24 months of observation, and little long-term evidence exists.10,22

Approximately 1 in 4 of children participating in CariedAway had untreated caries at baseline (1 in 3 for the COVID-19 sample), and 11% had preexisting sealants. Following treatment, the overall odds of dental caries decreased by approximately 20% in both study arms. The risk of incident dental caries was nearly identical in both treatment groups, resulting in a very small preventive fraction between the included interventions. Similarly, the data indicate no significant differences across treatment in the risk of first caries eruption or when modeling the total number of new dental caries experienced overall, nor is there sufficient evidence to indicate whether there are differences in treatment effect over time or based on the presence of disease at baseline. Dental sealants have an estimated 50% preventive fraction for caries compared to placebo, with research estimating the prevention of more than 3 million cavities attributable to sealants.35 The similarity in observed incidence from CariedAway may support a similar conclusion for the application of SDF.

In addition to clinical effectiveness, the simplicity and financial implications of a school-based SDF program can result in considerable cost savings to the public. A review of existing SDF treatment protocols identified application times as low as 10 seconds per tooth,12 suggesting that more children can be treated in less time. Use of SDF as a caries management strategy also reduces Medicaid program expenditures,36 is the most cost-effective option in populations with a high risk of dental caries,37 and is more cost-efficient compared to ART,13 although potential restrictions from Medicaid reimbursement may persist.36

In 2022, the American Medical Association approved a category III Current Procedural Terminology code authorizing nondental health care professionals to administer SDF, and research indicates that treatment of early childhood caries using SDF by physicians in primary care settings is both feasible and acceptable.38 Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry published guidance on physician use of SDF for caries management,39 and surveys of pediatricians by the American Academy of Pediatricians reveal an interest in and recognized need for SDF.40 More than one-fourth of participants in the SDF arm of the CariedAway trial were treated by registered nurses, and our results for incident caries over 4 years corroborate other findings on the effectiveness of nurses in providing SDF.41 School-based caries prevention may have greater student participation when school nurses partner with hygienists in the delivery of care,42 and our results empower nurses as primary agents in caries prevention. With more than 132 000 school nurses estimated to be currently in the US43 and given their growing involvement in oral health promotion and prevention,44 these findings can expand the scope of practice for both school nurses and family practices.

While the American Dental Association45 and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry46 include SDF in their clinical recommendations for caries management, known complications with SDF application include potential oral soft tissue irritation, temporary staining of the oral mucosa, and permanent staining of porous tooth structure.29 Despite thousands of SDF applications in CariedAway, we encountered no adverse events and received only 1 complaint regarding staining, which pertained to superficial skin staining from accidental spillage that was mistaken for bruising. Separate findings from CariedAway did not indicate a negative impact of SDF therapy on oral health-related quality of life, which included measures for aesthetic perceptions of the oral cavity.47 Other research concludes that a high proportion of parents of children treated with SDF remain satisfied with their child’s dental appearance,48,49 that aesthetic concerns are mitigated with posterior application,50 and that no differences were found in adverse events or aesthetic perceptions when comparing children treated with SDF vs sealant and ART.51

Limitations

As a pragmatic trial, there are concerns regarding subject attrition and any bias from external care. Our analysis used all available observations for study participants, considered a subset of participants that had equal rates of follow-up due to COVID-19, and identified any treated dentition by clinicians outside the CariedAway program. Additionally, the presented findings assessed caries prevalence inclusive of both children who did and did not begin the study with active untreated decay, which has, to our knowledge, not been reported previously, as those with untreated caries at baseline may have a higher risk of subsequent disease development. We also included multiple assessments of prevention, including any incidence of decay, overall prevalence, time to first eruption, and estimates at both the tooth and person levels. While attrition is a clear weakness, the pragmatic nature of the trial reflects the real-world experience of a school-based model that uses SDF for long-term caries management.

Conclusions

Untreated dental caries has maintained a 30-year position at the top of the global disease prevalence lists.52 Results from the CariedAway randomized clinical trial demonstrate the longitudinal effectiveness of SDF when used in school-based caries prevention and can be used by clinicians, practices, and communities in the global pursuit of oral health equity.

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Longitudinal caries incidence and the effect of sealants with ART compared to silver diamine fluoride, full sample

eFigure. CONSORT diagram, COVID-19 sample

eTable 2. Sample demographics overall and by treatment, COVID-19 sample

eTable 3. Longitudinal caries prevalence and the effect of sealants with ART compared to silver diamine fluoride, COVID-19 sample

eTable 4. Longitudinal caries incidence and the effect of sealants with ART compared to silver diamine fluoride, COVID-19 sample

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Bernabe E, Marcenes W, Hernandez CR, et al. ; GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators . Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):362-373. doi: 10.1177/0022034520908533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research . Dental caries (tooth decay) in children age 2 to 11. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries/children

- 3.World Health Organization . Draft global oral health action plan: 2023-2030. Accessed January 23, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-global-oral-health-action-plan-(2023-2030)

- 4.World Health Organization . WHO model lists of essential medicines. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.who.int/groups/expert-committee-on-selection-and-use-of-essential-medicines/essential-medicines-lists

- 5.Health Resources & Services Administration . Health workforce shortage areas. Accessed January 23, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas

- 6.Griffin S, Naavaal S, Scherrer C, Griffin PM, Harris K, Chattopadhyay S. School-based dental sealant programs prevent cavities and are cost-effective. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2233-2240. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabalén MB, Molina GF, Bono A, Burrow MF. Nonrestorative caries treatment: a systematic review update. Int Dent J. 2022;72(6):746-764. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashbour W, Gupta P, Worthington HV, Boyers D. Pit and fissure sealants versus fluoride varnishes for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11(11):CD003067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003067.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel N, Griffin SO, Linabarger M, Lesaja S. Impact of school sealant programs on oral health among youth and identification of potential barriers to implementation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2022;153(10):970-978.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2022.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira BH, Rajendra A, Veitz-Keenan A, Niederman R. The effect of silver diamine fluoride in preventing caries in the primary dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2019;53(1):24-32. doi: 10.1159/000488686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brignardello-Petersen R. Silver diamine fluoride seems to be effective in preventing and arresting root caries in older adults compared with placebo, but there is very low certainty in the magnitude of the benefit. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(1):e3. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan IG, Zheng FM, Gao SS, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. A review of the protocol of SDF therapy for arresting caries. Int Dent J. 2022;72(5):579-588. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gierth J, Coughlan J, Gkekas N, et al. Essential medicines for dental caries: cost-effectiveness of ART and SDF. Eur J Public Health. 2022;32(suppl 3). doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckac131.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horst JA. Silver fluoride as a treatment for dental caries. Adv Dent Res. 2018;29(1):135-140. doi: 10.1177/0022034517743750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford I, Norrie J. Pragmatic trials. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):454-463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruff RR, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride versus therapeutic sealants for the arrest and prevention of dental caries in low-income minority children: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):523. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2891-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruff RR, Barry-Godín T, Niederman R. Effect of silver diamine fluoride on caries arrest and prevention: the CariedAway school-based randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255458. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frencken JE. Atraumatic restorative treatment and minimal intervention dentistry. Br Dent J. 2017;223(3):183-189. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saber AM, El-Housseiny AA, Alamoudi NM. Atraumatic restorative treatment and interim therapeutic restoration: a review of the literature. Dent J (Basel). 2019;7(1):28. doi: 10.3390/dj7010028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gugnani N, Pandit IK, Srivastava N, Gupta M, Sharma M. International caries detection and assessment system (ICDAS): a new concept. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011;4(2):93-100. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration . Non-inferiority clinical trials to establish effectiveness: guidance for industry. Accessed January 23, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/78504/download

- 22.Liu BY, Lo EC, Chu CH, Lin HC. Randomized trial on fluorides and sealants for fissure caries prevention. J Dent Res. 2012;91(8):753-758. doi: 10.1177/0022034512452278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tunes da Silva G, Logan BR, Klein JP. Methods for equivalence and noninferiority testing. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(1)(suppl):120-127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mascha EJ, Sessler DI. Equivalence and noninferiority testing in regression models and repeated-measures designs. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(3):678-687. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318206f872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett S, Parpia T, Hayes R, Cousens S. Methods for the analysis of incidence rates in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(4):839-846. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.4.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng D, Mao L, Lin DY. Maximum likelihood estimation for semiparametric transformation models with interval-censored data. Biometrika. 2016;103(2):253-271. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asw013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starr JR, Ruff RR, Palmisano J, Goodson JM, Bukhari OM, Niederman R. Longitudinal caries prevalence in a comprehensive, multicomponent, school-based prevention program. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(3):224-233.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruff RR, Senthi S, Susser SR, Tsutsui A. Oral health, academic performance, and school absenteeism in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(2):111-121.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horst JA, Heima M. Prevention of dental caries by silver diamine fluoride. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2019;40(3):158-163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Llodra JC, Rodriguez A, Ferrer B, Menardia V, Ramos T, Morato M. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for caries reduction in primary teeth and first permanent molars of schoolchildren: 36-month clinical trial. J Dent Res. 2005;84(8):721-724. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira BH, Rajendra A, Veitz-Keenan A, Niederman R. The effect of silver diamine fluoride in preventing caries in the primary dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2019;53(1):24-32. doi: 10.1159/000488686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain A, Deshpande AN, Shah YS, Jaiswal V, Tailor B. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride and sodium fluoride varnish in preventing new carious lesion in preschoolers: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2023;16(1):1-8. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-2488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satyarup D, Mohanty S, Nagarajappa R, Mahapatra I, Dalai RP. Comparison of the effectiveness of 38% silver diamine fluoride and atraumatic restorative treatment for treating dental caries in a school setting: a randomized clinical trial. Dent Med Probl. 2022;59(2):217-223. doi: 10.17219/dmp/143547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monse B, Heinrich-Weltzien R, Mulder J, Holmgren C, van Palenstein Helderman WH. Caries preventive efficacy of silver diammine fluoride (SDF) and ART sealants in a school-based daily fluoride toothbrushing program in the Philippines. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffin SO, Wei L, Gooch BF, Weno K, Espinoza L. Vital signs: dental sealant use and untreated tooth decay among U.S. school-aged children. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(41):1141-1145. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6541e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johhnson B, Serban N, Griffin PM, Tomar SL. Projecting the economic impact of silver diamine fluoride on caries treatment expenditures and outcomes in young U.S. children. J Public Health Dent. 2019;79(3):215-221. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwendicke F, Göstemeyer G. Cost-effectiveness of root caries preventive treatments. J Dent. 2017;56:58-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein RS, Johnston B, Mackay K, Sanders J. Implementation of a primary care physician-led cavity clinic using silver diamine fluoride. J Public Health Dent. 2019;79(3):193-197. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Physician use of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) in dental caries management. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/sdf-guidance-for-physicians_aapd_2023.pdf

- 40.American Academy of Pediatrics . Pediatricians and pediatric oral health: knowledge and attitudes about silver diamine fluoride in pediatric practice. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://downloads.aap.org/DOPCSP/AAPSDFFullSurveyFinalReport.pdf

- 41.Ruff RR, Godín TB, Niederman R. The effectiveness of medical nurses in treating children with silver diamine fluoride in a school-based caries prevention program. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. Published online October 24, 2023. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mattheus D, Loos JR, Vogeler A. The development and implementation of a school-based dental sealant program for Hawaii public schools. J Sch Health. 2024;94(1):87-95. doi: 10.1111/josh.13401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willgerodt MA, Brock DM, Maughan ED. Public school nursing practice in the United States. J Sch Nurs. 2018;34(3):232-244. doi: 10.1177/1059840517752456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buerlein J. Promoting children’s oral health. a role for school nurses in prevention, education, and coordination. NASN Sch Nurse. 2010;25(1):26-29. doi: 10.1177/1942602X09353053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: a report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(10):837-849.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crystal YO, Marghalani AA, Ureles SD, et al. Use of silver diamine fluoride for dental caries management in children and adolescents, including those with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39(5):135-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruff RR, Barry Godín TJ, Small TM, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride, atraumatic restorations, and oral health-related quality of life in children aged 5-13 years: results from the CariedAway school-based cluster randomized trial. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02159-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huebner CE, Milgrom P, Cunha-Cruz J, et al. Parents’ satisfaction with silver diamine fluoride treatment of carious lesions in children. J Dent Child (Chic). 2020;87(1):4-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duangthip D, Fung MHT, Wong MCM, Chu CH, Lo ECM. Adverse effects of silver diamine fluoride treatment among preschool children. J Dent Res. 2018;97(4):395-401. doi: 10.1177/0022034517746678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crystal YO, Janal MN, Hamilton DS, Niederman R. Parental perceptions and acceptance of silver diamine fluoride staining. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(7):510-518.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vollú AL, Rodrigues GF, Rougemount Teixeira RV, et al. Efficacy of 30% silver diamine fluoride compared to atraumatic restorative treatment on dentine caries arrestment in primary molars of preschool children: a 12-months parallel randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dent. 2019;88:103165. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization . Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Longitudinal caries incidence and the effect of sealants with ART compared to silver diamine fluoride, full sample

eFigure. CONSORT diagram, COVID-19 sample

eTable 2. Sample demographics overall and by treatment, COVID-19 sample

eTable 3. Longitudinal caries prevalence and the effect of sealants with ART compared to silver diamine fluoride, COVID-19 sample

eTable 4. Longitudinal caries incidence and the effect of sealants with ART compared to silver diamine fluoride, COVID-19 sample

Data sharing statement