Abstract

DNA from the centromere region of linkage group (LG) VII of Neurospora crassa was cloned previously from a yeast artificial chromosome library and was found to be atypical of Neurospora DNA in both composition (AT rich) and complexity (repetitive). We have determined the DNA sequence of a small portion (∼16.1 kb) of this region and have identified a cluster of three new retrotransposon-like elements as well as degenerate fragments from the 3′ end of Tad, a previously identified LINE-like retrotransposon. This region contains a novel full-length but nonmobile copia-like element, designated Tcen, that is only associated with centromere regions. Adjacent DNA contains portions of a gypsy-like element designated Tgl1. A third new element, Tgl2, shows similarity to the Ty3 transposon of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. All three of these elements appear to be degenerate, containing predominantly transition mutations suggestive of the repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) process. Three new simple DNA repeats have also been identified in the LG VII centromere region. While Tcen elements map exclusively to centromere regions by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, the defective Tad elements appear to occur most frequently within centromeres but are also found at other loci including telomeres. The characteristics and arrangement of these elements are similar to those seen in the Drosophila centromere, but the relative abundance of each class of repeats, as well as the sequence degeneracy of the transposon-like elements, is unique to Neurospora. These results suggest that the Neurospora centromere is heterochromatic and regional in character, more similar to centromeres of Drosophila than to those of most single-cell yeasts.

Centromeres are regions of chromosomes that direct formation of the kinetochore and its subsequent attachment to the spindle, enabling the faithful segregation of the genetic material during cell division. This chromosomal domain, found in all eukaryotes, is functionally conserved but structurally quite divergent between organisms. The overall size and sequence complexity of centromeres generally appears to parallel the developmental complexity of the organism. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for example, the centromere is small, consisting of only approximately 200 bp for full function. In higher eukaryotes, however, centromeric regions of the genome not only are much larger (up to 5 Mb in length [see reference 55 for review]) but show no apparent sequence conservation and have been referred to as “regional” centromeres.

Despite recent advances in the development of higher eukaryotic experimental systems, relatively little is known about the sequence constituents of centromeres and centric heterochromatin in complex organisms. For Drosophila, the centromere of a minichromosome has been mapped by deletion analysis, and the minimal sequences required for function are now being identified (37, 67). The sequence components necessary for full centromere function appear to include transposable elements of several types as well as low-complexity satellite DNAs (67). The apparent absence of a defined sequence that is responsible for kinetochore formation, as is seen in S. cerevisiae, suggests a redundant, nonsequence-specific initiation event leading to centromere and/or kinetochore formation. There is also evidence in vertebrates for similar redundancy, i.e., Indian muntjac centromeres can be fractionated into multiple individual kinetochore-like units (76). Indirect evidence from humans suggests that megabase arrays of α-satellite or alphoid DNAs, which are a family of A+T-rich 171-bp tandem repeats, are associated with active centromeres (46) and may be sufficient for centromere function (23, 68). Centromere activity can be observed, however, in activated human neocentromeres lacking alphoid repeats (19).

The large size of regional centromeres may be important for the additional functions that have been attributed to centromeres of higher eukaryotes, including chromosome adhesion in achiasmate disjunction (32), as well as providing domains of specialized chromatin structure (heterochromatin) in which euchromatic gene transcription and recombination are both repressed. The characteristics of regional centromeric DNA may also reflect an underlying mechanism by which chromatin structure nucleates kinetochore formation. Several regional centromeres display an epigenetic control phenomenon called centromere activation. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, formation of the centromere into an active state can require multiple cell divisions after introduction of naked minichromosome DNA (66). In other organisms, aberrant chromosomes can form neocentromeres in locations differing from the original centromere, resulting in a mixture of cells containing a chromosome with one site or the other acting as the centromere (1, 6, 69).

The regional heterochromatic character of centromeres in complex organisms, however, may result from the accumulation of repeated sequence elements. One consequence of recombinational repression in heterochromatic regions may be the accumulation of mobile genetic elements (13). The prevailing model explaining the observed excess of transposons in centric heterochromatin holds that chromosome rearrangements due to ectopic recombination between similar transposons at different sites in the genome may lead to decreased fitness and selection against such ectopic insertions (12). Alternatively, the insertion of transposons into genic regions may have negative effects on the fitness of individuals in the population, resulting in fewer elements in euchromatic regions of the genome (28). It is possible, however, that repeated sequence elements in some circumstances may have positive effects on fitness rather than just neutral or negative effects. Like centromeric domains, telomeric and subtelomeric regions of most organisms are also regions of specialized chromatin structure and are home to numerous repeated elements (58, 70, 75). The telomerase-elongated simple DNA sequence repeats at the end of the chromosomes of most eukaryotes are essential elements for continued chromosomal end replication and for segregation of the genome. Remarkably, telomeric sequences can function in place of centromeric heterochromatin in Drosophila in the formation of neocentromeres (2, 6, 56, 73). In Drosophila, telomere functions are probably served by the HeT-A and Tart retrotransposons that are found at all chromosomal termini (14, 43). The cell apparently has taken advantage of such elements to serve an essential function.

In multicellular fungi, little is known about centromere structure. The chromosomes of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa show regions of heavy, intense staining (heterochromatin) in meiosis (44, 64). Centola and Carbon (10) cloned and partially characterized a contiguous set of artificial yeast chromosomes (YACs) containing DNA that spanned the centromere region of linkage group (LG) VII of Neurospora. This region, approximately 450 kb in length, was found to be both A+T rich and recombination deficient. In addition, they identified a centromere-specific repeated DNA sequence. Comparison of the sequence of this centromere-specific clone to homologous DNAs from elsewhere in the genome suggested that they had undergone repeat-induced point mutation (RIP), a process that scans the genome of Neurospora for repeated DNAs during the sexual cycle and induces GC to AT transition mutations, and often DNA methylation, specific to the duplicated sequences (61).

In this study, we have further characterized the centromere region of LG VII of Neurospora and have discovered a nested cluster of putative transposable elements and simple sequence repeats. A repeated DNA sequence previously found to map to centromere-linked regions of the Neurospora genome (10) is now shown to be a copia-like element (named Tcen) which is novel in that it is the only known transposon to be shown to map exclusively to centromere regions. In addition, the region contains the degenerate remains of several other transposons, as well as three different low-complexity DNAs organized in a tightly nested arrangement. Although these features have yet to be associated with kinetochore formation, the structural similarity of the Neurospora centromere VII region to the centromere of the Drosophila Dp1187 minichromosome (37, 67) suggests that Neurospora kinetochore-forming regions may be similarly redundant and nonspecific.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions.

Standard Neurospora (15), yeast (63), and Escherichia coli (41) culture conditions and media were used.

Neurospora strains.

A standard Oak Ridge strain, 74-OR23-1VA (FGSC 2489), and the multicent 2 (un-2 arg-5 thi-4 pyr-1 lys-1 inl nic-3 ars) X Mauriceville 1-c restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) mapping kit (45), using strains derived from ordered asci (FGSC 4450-4488 and 2225), were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (FGSC), Department of Microbiology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

DNA manipulations.

Neurospora DNA was isolated as previously described (62). Restriction digests were carried out by using buffers and conditions specified by the manufacturer. Restriction digests were fractionated on 1.0% agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes by using the Posiblot system (Stratagene). Southern transfer was to MagnaGraph nylon membranes, and hybridization was performed overnight at 65°C in 10% dextran sulfate–1.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate–1.0 M NaCl. After hybridization, membranes were washed once at room temperature (15 min) and three times at 65°C (15 min each time) in 300 mM NaCl–30 mM sodium citrate–1.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Hybridization probes were prepared by the random oligomer primer method with the Prime-It II kit from Stratagene.

Probes used in Southern blot hybridizations.

The dTad probes used to hybridize to RFLP blots were (i) Tad B, an internal 500-bp EcoRI fragment of Tad1-1 (7), and (ii) dTad3, a 780-bp BamHI to PacI fragment from the 5′ flanking region of the BamHI clone containing Tad1-1 (35). The probes used for the Neurospora genomic Southern blot shown in Fig. 7B were as follows: (i) for the Sma repeat, the 212-bp insert of pSmarep1; and (ii) for the Tsp repeat, the 250-bp insert of pTsprep3. The probes used for the YAC-containing S. cerevisiae genomic Southern blot shown in Fig. 6A were as follows: (i) for YAC ends, a 2.5-kb SalI to BamHI fragment from pDH25 containing the Hph gene; (ii) for Tad, the dTad3 probe described above; and (iii) for Tcen, a 220-bp AvaI fragment from pBS515, containing a part of the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) of Tcen.

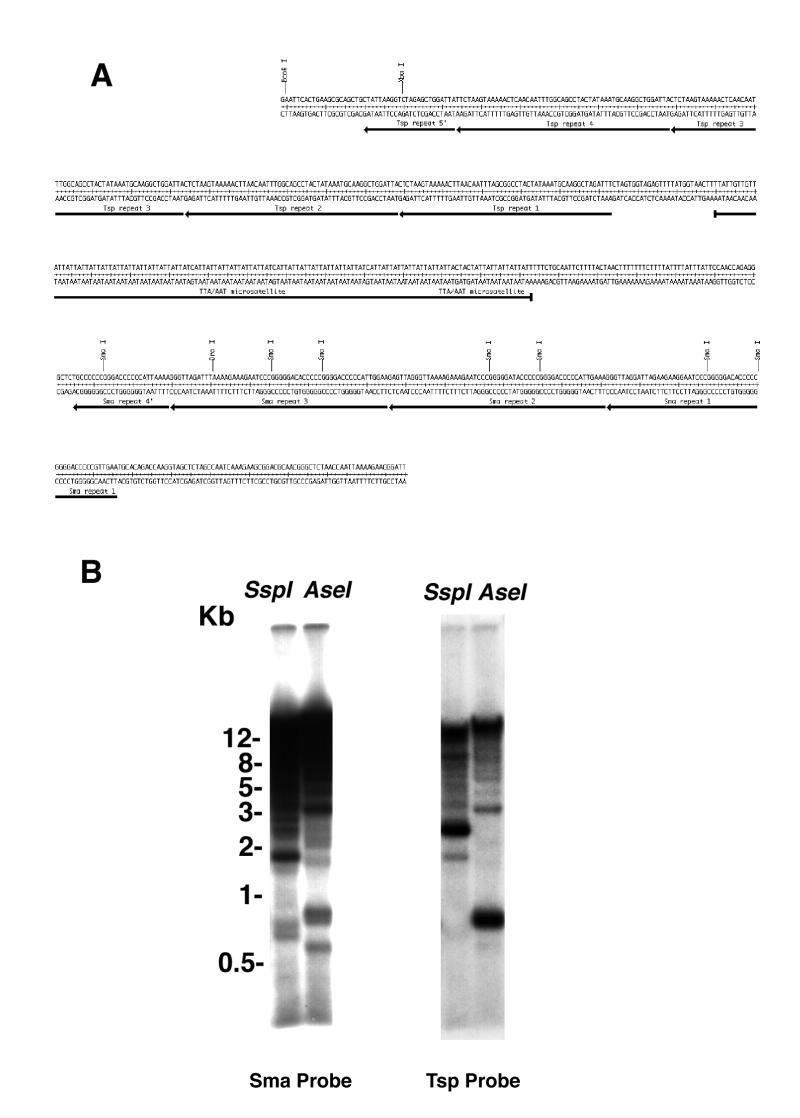

FIG. 7.

Analysis of simple repeated DNAs from the LG VII centromere region. (A) The nucleotide sequence of the rescued centromeric region containing three classes of simple repetitive DNAs. Each repeat is shown underlined, and the individual Tsp and Sma satellite subunits are additionally delineated by arrows. (B) Southern blot of Neurospora genomic DNA, probed sequentially with labeled DNA segments containing the Sma and Tsp repeats. DNA was isolated, digested with either AseI or SspI restriction enzyme, and fractionated and blotted as described in Materials and Methods. The Sma repeat is repeated at a relatively high copy number within the Neurospora genome. The Tsp repeat also appears to be repeated but at a much lower copy number. The images were processed as described for Fig. 6.

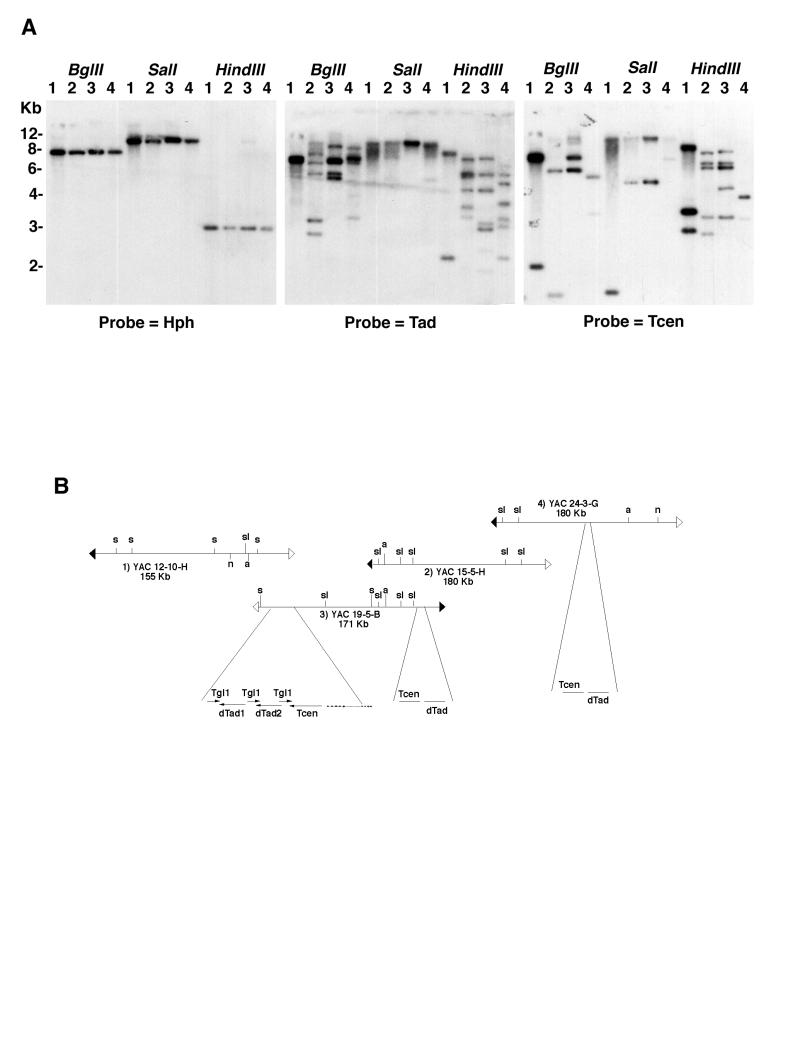

FIG. 6.

Distribution of Tcen and Tad homologous sequences across the LG VII centromere region. (A) Southern blot of genomic DNAs from yeast strains that carry the four YACs shown in Fig. 1. The lanes contained DNA from strains containing YAC 12-10-H (lanes 1), YAC 15-6-H (lanes 2), YAC 19-5-B (lanes 3), and YAC 24-3-G (lanes 4). Genomic DNA was isolated and digested with either BglII, SalI, or HindIII restriction enzyme. The DNAs were fractionated and blotted as described in Material and Methods and were sequentially probed with (i) the hph gene (a YAC-specific end probe), (ii) a Tcen LTR-specific probe, and (iii) an internal Tad probe. Multiple overlapping bands can be observed in the autoradiograms from the Tcen and Tad probings. (B) A schematic diagram showing the probable location of Tcen and Tad clusters in the LG VII centromere region. Autoradiograms were scanned, and the panel was created with Adobe Photoshop 4.0.

PCR conditions and primers used.

Plasmid DNA from p10-8-H SacI was subjected to PCR amplification as previously described (47, 57). The primers used to amplify the Sma repeats were primer Smart, 5′ TCCGGATCCAACCAGAGGGCTCTGC 3′, and primer Smalf, 5′ TCTAGATCTACCTTGGTCTGTGCATTC 3′. The primers used to amplify the Tsp repeat were primer Tsprt, 5′ TGCATGCATGCGCAAGCTGCTATTAAG 3′, and primer Tsplf, 5′ AAACTGCAGGATCCATAAAACTCTACCACTAG 3′. Primers Smalf and Tsprt were also used to amplify the clustered three-repeat region. The primers used to sequence from a variety of Tcen LTR clones were primer CENR5, 5′ CCACATCCAACTGCTTGATTTCG 3′, and primer CENR3, 5′ CYRGTCTTTRRCGTTGYTRC 3′. The PCR fragments were cloned into plasmid vectors (pBluescript KS+ [Stratagene] or pGEM-T [Promega]).

DNA sequencing and analysis.

Manual sequencing was done by using a Sequenase kit from U.S. Biochemical. Automated sequencing of the plasmids p10-8-H SacI and p12-10-H ClaI was performed by primer walking, at the University of California San Francisco Biomolecular Resource Center, by using an Applied Biosystems sequencer. Other automated sequencing was performed on 19 plasmid clones from a genomic library containing EcoRI inserts that hybridize to centromere DNA (10), with the assistance of M. Centola at the National Institutes of Health. Sequence DNA repeats were compiled into a data set, and each individual sequence was compared to the set by using the FastA algorithm (52) from the Genetics Computer Group package on a Silicon Graphic workstation.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the sequenced DNA from the Neurospora centromere VII region is AF079510.

RESULTS

DNA sequence analysis of a 16-kb region of N. crassa centromere VII.

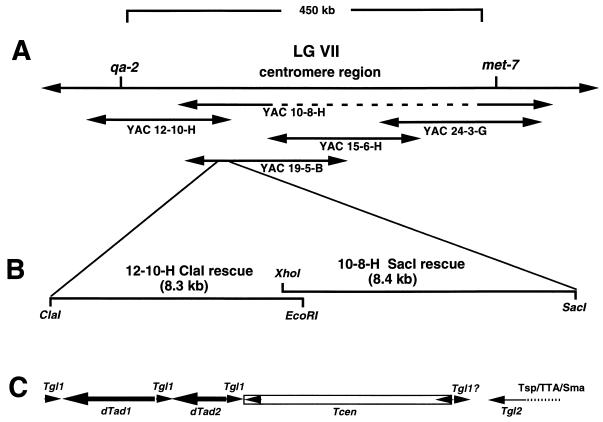

A contiguous set of YACs containing DNA from the LG VII region of Neurospora was previously cloned and physically mapped in relation to the Neurospora genome (10) (Fig. 1A). To gain further information on the properties of Neurospora centromeric DNA, we sequenced the inserts of two subclones that had been isolated by plasmid rescue from the overlap region of YAC 12-10-H and YAC 10-8-H (10). These subclones, referred to as p12-10-H ClaI and p10-8-H SacI, respectively, contain DNA segments from the region located approximately 120 kb centromere proximal to the qa gene cluster (Fig. 1B) and are themselves overlapping by approximately 700 bp. Three lines of evidence support this contention. Hybridization of the overlapping fragment to genomic DNA in quantitative Southern blots yielded only a single strong band (10). In addition, Southern blot analysis revealed that both rescue inserts hybridized to bands of the same size in Neurospora genomic DNA and in DNA from the YACs from which the subclones were derived (data not shown). Finally, DNA sequences determined from the overlapping region were found to be identical in both. This confirms the continuity of the two clones, since only a single genomic copy of the sequences hybridizes well and the likelihood of sequence identity in large repetitive elements in Neurospora is very low due to RIP (61).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the structure of the centromere of LG VII and the region that was subcloned and sequenced. (A) The centromeric interval between the qa-2 and met-7 genes on LG VII and the YAC clones that cover this region. YAC 10-8-H is internally deleted (dotted line) but physical mapping demonstrates greater than 80 kb of colinearity with the left end of YAC 19-5-B, in the region of overlap with YAC 12-10-H (11). (B) The two overlapping regions that were subcloned from YACs by plasmid rescue (10). (C) The arrangement of transposons, transposon fragments, and simple sequence repeats within the subcloned region shown in panel B at the same scale.

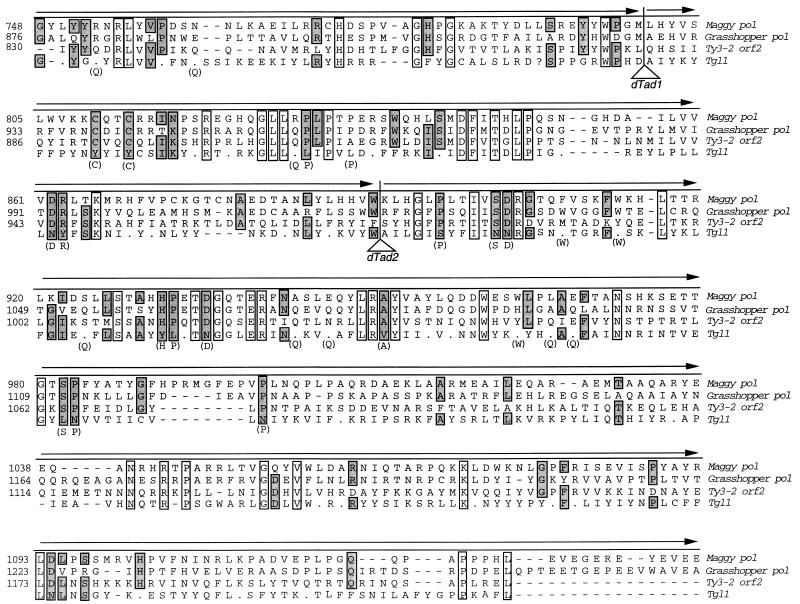

Tgl1, a multiply interrupted gypsy-like retroelement.

The complete DNA sequences of the two rescue clones were determined, and a schematic representation of the identified elements occurring within these sequences is shown in Fig. 1C. On the left (qa cluster-proximal) end, we found a degenerate transposon-like sequence with similarity to the reverse transcriptase regions of gypsy-like retrotransposons. This first element we designate Tgl1, for transposon gypsy like. Blastx sequence comparisons revealed contiguous similarity to gypsy-like elements at a P = 10−8 level of significance (3). Because repeated DNA sequences in Neurospora undergo extensive mutational alterations during the sexual cycle due to RIP, the likelihood that this level of sequence similarity is significant is high, given that the DNA sequence reveals a dinucleotide bias indicative of having undergone RIP (8, 22). This putative transposon appears to be interrupted by at least two large insertions, the first of which is a large 3′ end fragment of a LINE-like retroelement with homology to the Tad element of Neurospora. The second is another, smaller 3′ end fragment of a separate, degenerate Tad-like element. It is possible that a fourth fragment of the Tgl1 element is located on the right (centromere-proximal) end of a third insertion, which is a full-length, but again degenerate, transposon-like element (Tcen) of the copia class. A composite of the three putative Tgl1 fragments was constructed, and a comparison of amino acid alignments of the pol region from gypsy-like elements versus the matching region of a theoretical translation of the composite of the split Tgl1 is shown in Fig. 2. The comparison clearly indicated that the three Tgl1 fragments can be joined to form a sequence having continuous and significant homology to the pol region of gypsy-like elements. The bracketed residues represent likely progenitor amino acids; i.e., they are specified by codons that have undergone a single GC to AT transition due to RIP. Together, these similarities demonstrate that at least a portion of the Tgl1 transposon has been disrupted by insertion of two dTad fragments and that the likely progenitor element of Tgl1 was a gypsy class transposon.

FIG. 2.

A theoretical translation of the composite of the three interrupted Tgl1 fragments denoted in Fig. 1C. Amino acid sequences of the pol region of three fungal Gypsy-like transposons, Ty3 (25), Maggy (20), and Grasshopper (17), were aligned by using the CLUSTAL algorithm (27), and the putative Tgl1 amino acids were subsequently aligned by hand. Raw sequence data was used for the translation of Tgl1, but some frameshifts were included to improve the alignment. Periods in the sequence refer to translational stop codons, and dashes indicate spaces inserted by the algorithm, or in the Tgl1 case, by hand. Regions of identity are boxed with open boxes if all four residues are identical or with shaded boxes to indicate three of four identities. Possible progenitor amino acids that can be derived from the nucleotide sequence, if one GC to AT transition is posited, are bracketed. The dTad1 and dTad2 insertion sites are indicated by triangles.

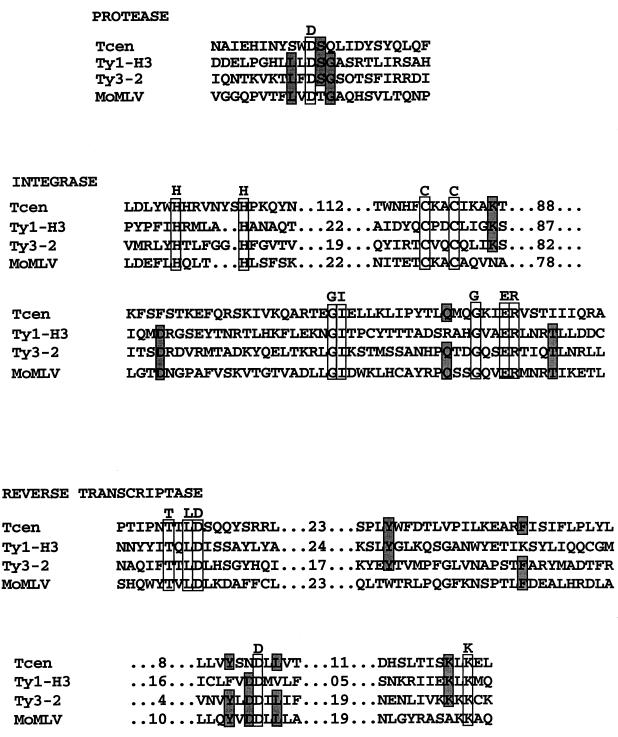

The Tad-like elements dTad1 and dTad2 are relics of two previous transposition events.

Tad is a LINE-like retrotransposon found in progeny of an N. crassa strain isolated from Adiopodoume, Ivory Coast (35). No active Tad elements exist in standard laboratory strains of Neurospora, including the strain used to construct the Centola YAC library (33). Only degenerate copies of Tad that have undergone numerous GC to AT transitions, as well as some transversions, remain in the genome (33a). This has been noted as evidence that Tad has transposed in these strains in the past and was then subjected to RIP (34). Previously isolated de novo jumps of Tad from strains with active elements have all been found to be full-length copies (7, 35). This was surprising given that in most other organisms that contain LINE-like elements the most frequently observed structures are 3′ end fragments (29). Here we describe two new Tad-like elements in the centromere region of LG VII. Both are 3′ end fragments and are most likely the result of de novo jumps into the Tgl1 sequence some time ago. The dTad1 fragment is 3,475 bp in length, consists of sequences homologous to known Tads, and extends from a few base pairs upstream of the consensus 3′ terminus to approximately the middle of the full-length element, terminating in the ORF2 region. The dTad2 element is shorter, spanning only 1,404 bp, and also begins from sequences homologous to the consensus 3′ terminus of Tad. In this case, however, the element displays target-site duplications (TSDs) of 14 bp at the ends of the Tad homology, typical of TSDs of known Tads (7). The presence of TSDs confirms that this element is a relic of an uninterrupted, de novo jump of a 3′ end fragment of Tad or a closely related transposon.

The relatedness of the dTad sequences to an active Tad element and to each other, as well as to other dTads elsewhere in the genome, is shown in Table 1. The G+C content of the dTad elements is strikingly lower than that of an active element, Tad1-1, being reduced from 58.5% to approximately 30% or less. The mutational changes in the sequences leading to this dramatic difference are indicative of RIP, with almost all of the differences due to transition mutations. Pairwise comparison of the Tad-like sequences to one another reveals higher levels of sequence identity between the dTad elements than between each dTad and Tad1-1. Two possible explanations of this observation are (i) these elements have a common ancestor different from Tad and (ii) the relative increase in identities is due to the nucleotide bias of RIP, which should frequently mutate the same GC residues thus resulting in products that are more similar to each other than to the original DNA. The range of observed transversion frequencies should serve to distinguish these possibilities, with the expectation that if the ancestor was different from Tad then the range of transversions observed should be correspondingly lower between dTads than between each dTad and Tad1-1. The observed ranges are quite similar, however, thus suggesting that the increased identity among dTads is due to RIP convergence and not to a common ancestor other than Tad. Interestingly, the arrangement of dTad1 and dTad2 results in a tandem duplication of approximately 1,400 bp. Despite the fact that tandem duplications are known to be highly prone to both RIP and recombinational deletion in Neurospora (60), there is no evidence that the dTad1-dTad2 region has undergone significantly more RIP changes than occur at other nontandem dTad duplications in the genome.

TABLE 1.

Pairwise comparison of Tad1-1 and four Tad-like elements indicating relative nucleotide differences and identitiesa

| Tad-like element (genomic location, % G+C) |

Tad1-1

|

dTad1

|

dTad2

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % id | % ts | % tv | % id | % ts | % tv | % id | % ts | % tv | |

| dTad1 (1210H, 29.9) | 59.4 | 34.6 | 5.9 | ||||||

| dTad2 (1210H, 32.4) | 58.1 | 34.3 | 7.7 | 72.8 | 23.7 | 3.5 | |||

| dTad3 (Cen III, 29.3) | 50.0 | 36.9 | 13.1 | 72 | 22 | 5.8 | 71 | 23.4 | 5.7 |

| dTad4 (Telo IVL, 25.4) | 55.6 | 39.1 | 5.2 | 66.6 | 26.1 | 7.3 | 69.5 | 24.9 | 5.6 |

Sequences were hand aligned to maximize colinearity of the sequence. Percentages were figured with only the aligned portion of the two sequences, ignoring small insertions and deletions. id, nucleotide identity; ts, transition mutation; tv, transversion mutation. Cen III, centromere region of LG III; Telo IVL, telomere region of LG IV L. The 1210H genomic location refers to the LG VII region discussed in this study. The G+C content of Tad1-1 is 58.5%.

Analysis of additional dTad elements in the Neurospora genome.

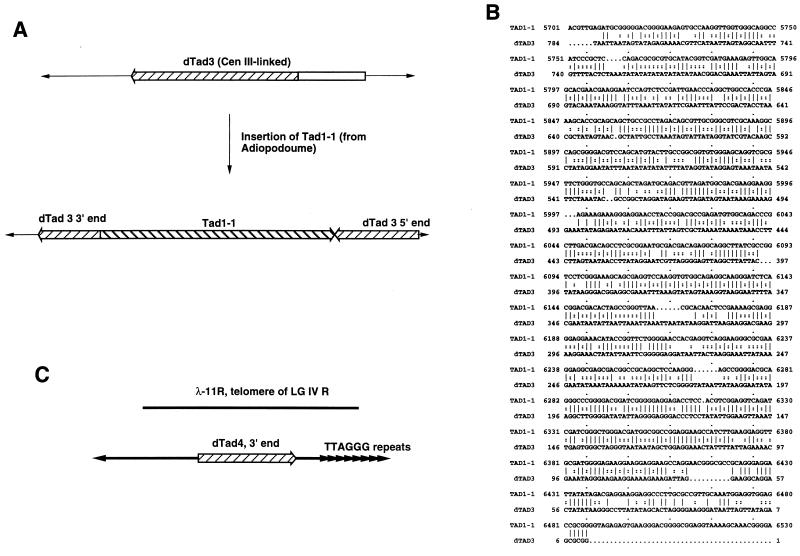

The low level of sequence identity between Tad and dTad elements made it quite difficult to identify sequences as being related to Tad by standard database searches with Blast or FastA (3, 52, 71). However, the increased sequence identity of dTads to one another due to RIP convergence allowed us to identify a family of such repeated sequences by using a data set of dTad and other Neurospora repeated sequences to compare to a given repeated sequence (see Materials and Methods). Using this data set, we identified two previously unknown Neurospora sequences in the GenBank database as belonging to the dTad family of relic transposons. These sequences are designated dTad3 and dTad4 and are located tightly linked to centromere III and ∼200 bp subtelomeric of the TTAGGG repeat on the left arm of LG IV, respectively (Fig. 3A and 3C).

FIG. 3.

Defective Tad elements found elsewhere in the genome of N. crassa. (A) A schematic representation of the de novo insertion event of the Tad1-1 LINE-like transposon into the dTad3 element residing near the centromere of LG III (7). (B) Alignment of the 3′ ends of dTad3 and Tad1-1. Identities are indicated by solid lines, and transition mutations are shown as double dots. The alignment demonstrates substantial colinearity of the sequence and nearly 90% sequence similarity if changes due to RIP are taken into account (see Table 1). (C) A schematic representation of a subtelomeric dTad element found approximately 200 bp internal to the TTAGGG telomere repeats of LG IV R, derived from previously published sequence from the telomere-specific clone lambda-11R (59).

An example of the difficulty in discerning the identities of these repeated DNAs is illustrated by the sequence of dTad3, which was previously identified as the native repetitive target sequence into which Tad1-1 integrated subsequent to introduction of active Tads from the Adiopodoume strain (7). Tad1-1 was isolated on an 8-kb BamHI fragment, with the active element beginning 785 bp from one end of the clone (Fig. 3A). DNA spanning the 785 bp before the start of Tad1-1, as well as several hundred nucleotides after the end of Tad1-1, was also sequenced but showed no significant similarity to GenBank entries or the Tad1-1 or other sequenced Tad elements. Only after FastA sequence comparisons of dTad3 with a data set of repeated DNAs containing dTad1 and dTad2, as well as with other dTads that were cloned from a random plasmid library, were examined did the identity of dTad3 become obvious. FastA searches found recognizable similarities between dTad3 and other, less degenerate dTad elements but not to Tad1-1. The intermediate dTads did show recognizable similarity to active Tads. Hand alignment of dTad3 and Tad1-1 revealed their colinearity, and the sequences were punctuated with numerous directional GC to AT transition mutations including several small deletions, insertions, and transition mutations (Fig. 3B). Similarly, an unknown sequence on a λ clone containing telomere repeats, previously mapped to the left end of LG IV, was found to be a dTad element (59) (Fig. 3C).

To determine the range of genomic locations of dTads within Neurospora, we probed DNA of segregants from ordered asci of a cross between a multiply centromere-marked strain and a highly polymorphic parent (the multicent 2 molecular mapping kit, FGSC) (45). Of nine RFLPs analyzed using two Tad-related probes, we found that five showed perfect centromere segregation (LG I, II, III, VI, and VII), one showed close linkage to centromere III and three segregated as loci located elsewhere in the genome. (These data will be deposited along with other RFLP data with the Neurospora Genome Project.)

Tcen, a copia-like retrotransposon.

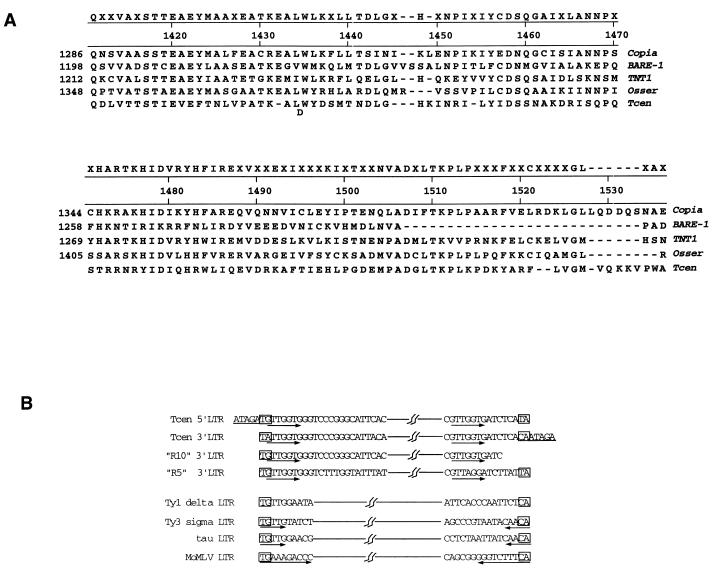

Centola and Carbon (10) identified and sequenced a 530-bp LG VII centromere-specific repeated DNA, compared its sequence to two similar repeats cloned from a plasmid library, and suggested that these DNAs had been subjected to RIP. We were interested in determining the overall extent of this repeat in order to determine its nature. We determined the flanking sequences of these three repeat copies in both directions and found that the nucleotide homology quickly dropped off in one direction but continued for a considerable distance in the other direction. We then derived a consensus sequence that more closely resembled a putative progenitor sequence by assuming that these DNAs had undergone RIP. This GC consensus was derived by taking G or C in place of A or T in any position where one of the compared sequences contained a G or C. The resulting DNA sequence was translated and homology searches were carried out at the protein level. This “de-RIP” approach yielded clear evidence that the putative progenitor of this particular region contained an RNase H domain with significant similarity to those of copia-like, LTR-containing retrotransposons (Fig. 4A). Further structural evidence that the progenitor was a transposon of this class is that the RNase H domain of Tcen is the closest of the pol-derived polypeptides to the 3′ LTR, typical of copia-like transposons; whereas, in gypsy-like elements, the integrase domain and the envelope-like polypeptides are 3′ LTR proximal (4). This suggests that the original region identified by Centola and Carbon is in fact the 3′ LTR (the rightward LTR at the end of the primary transcript).

FIG. 4.

Amino acid alignment of Tcen with the RNase H region of four known copia-like transposons. (A) Sequences were aligned as in Fig. 2, but a GC consensus sequence of Tcen was first derived from a comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the ends of three different copies of Tcen. If any of the three sequences contained a G or C rather than an A or T, this was used for the consensus sequence (to correct for RIP-induced transitions). Theoretical translation of the consensus results in an open reading frame with substantial similarity to the corresponding regions of the copia-like elements shown (Tnt1 [21], BARE-1 [42], Osser [38]). (B) Alignment of LTR end sequences from Tcen, two other unlinked Tcen elements (R5 and R10), three classes of transposons from S. cerevisiae (Ty1, Ty3, and tau), and retrovirus Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) (see reference 4). TSDs flanking Tcen are underlined, TG and CA end elements are boxed, and terminal duplications (inverted or direct) are indicated by arrows.

Final confirmation of the identity of this sequence as a copia-like element was obtained when the 5′ LTR was discovered approximately 6 kb upstream. A comparison of the ends of these LTR sequences, together with two other examples of highly similar 3′ LTRs from elsewhere in the genome, as well as with the ends of LTRs from two yeast transposons (Ty1 and Ty3) and Moloney murine leukemia virus, is shown in Fig. 4B. There are clear indications that these sequences are indeed LTRs. The TG and CA dinucleotides that are essential for integrase function, located at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the LTRs, respectively, are conserved. However, some of the end TG and CA dinucleotides in the LTRs shown in Fig. 4B are apparently mutated to TA. This is not unexpected, since TG/CA is the dinucleotide most frequently mutated by the RIP mechanism (8, 22). Also, a 5-nucleotide direct repeat, ATAGA, is present just upstream and downstream of the ends of the Neurospora consensus LTRs. This 5-bp sequence is typical in size for the TSDs generated by the integrase upon insertion of a copia-like cDNA copy into the genome. Another frequently observed (but not essential, see Ty1 in Fig. 4B) motif of the LTR ends is the presence of short inverted repeats extending inward from the initial TG and CA inverted repeat. By contrast, Tcen LTRs appear to have short direct repeats near the ends of the LTRs.

Amino acid sequence motifs diagnostic of transposons were also identified within Tcen. An alignment of the conserved regions of the pol polyprotein from several retroelements with those of the similar regions from the sequence of Tcen is presented in Fig. 5. Unlike “live” transposons, there are not detectable open reading frames of the expected length in Tcen. The aligned residues were derived from the predicted areas of the Tcen element, assuming its structure is similar to that of other copia-like elements, and several stop codons and occasional frameshifts were ignored in order to determine the optimal alignment. Despite this caveat, it is obvious that the remnants of the protease, integrase, and reverse transcriptase domains from the pol polypeptide regions can be clearly distinguished. The remains of a metal-binding domain in the presumed area of the gag polypeptide were also found (data not shown). Discovery of the precise reading frame(s) that encodes these potential elements will require either further analysis of several more degenerate copies of Tcen or the isolation and sequencing of a live Tcen element, if one exists, from a wild isolate of Neurospora or a related organism. Previous mapping of the resident genomic Tcen copies by RFLP analysis demonstrated the unique localization of this element to the centromere regions (10). Over 20 individual RFLPs showed strict first-division segregation patterns when blots of genomic DNA from strains derived from ordered asci were hybridized by using two probes containing DNA from Tcen (10). Northern blots of total Neurospora RNA show no transcripts when probed with Tcen sequences (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Alignment of the critical regions of the various domains of the pol region of known retroelements and Tcen. Alignment of the protease, integrase, and reverse transcriptase regions was as described previously (4). The homologies within each domain of the Tcen element were found in the expected regions, and the order of the homologous domains was similar to that within known copia-like transposons. Amino acids shared by all four elements are boxed and indicated above the aligned sequence; regions of similarity are also boxed and shaded. No GC consensus in the translation of Tcen was used in this alignment.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that the centromere-specific repeated sequence, Tcen, is derived from a transposable element that either showed unusual target-site specificity or in the period between the time when the element was last active in Neurospora and the present, the noncentromeric copies were deleted from the genome or from the population by selection forces.

Clustered dTad and Tcen elements in the LG VII centromere region.

The clustering of transposable elements in the sequenced 16 kb suggested that these elements might show further clustering at other sites in the LG VII centromere region. To assess this possibility, we probed a Southern blot of genomic DNAs from the four S. cerevisiae strains containing the YAC clones that span the centromere region of LG VII. The results of the consecutive probing of the same blot with a unique probe to one end of the YACs (hph), as well as with a dTad3 probe and a Tcen 3′ LTR probe, are shown in Fig. 6A. These data clearly demonstrate the presence of multiple copies of both dTad and Tcen in this region and also show indications (common bands) of clustering of these elements. The prior physical mapping of SalI sites within this contig (10) allowed us to identify two additional clustering regions (Fig. 6B), but there may be other clusters that are not easily identifiable. An additional indication that other clusters exist within the genome came from the identification of several cosmid clones from the Sachs-Orbach library (50) that hybridize to both dTad and Tcen probes. Apparently, the Neurospora LG VII centromeric region is similarly organized to that of the Drosophila minichromosome Dp1187 centromere region, with its islands of complex DNA composed of transposable elements surrounded by a sea of simple repeated DNA (37).

Simple sequence-repeated elements in the LG VII centromere of Neurospora.

Simple sequence-repeated DNAs in the centromere regions of various organisms have long been conjectured to play functional roles in centromere formation. Recent evidence supports these suggestions, at least in the case of Drosophila, where the 1.672-38 satellite (AATAT)n and the 1.705-42 satellite (AAGAG)n (39, 40) appear to be necessary for full centromere function, along with the Bora-Bora island, a more complex region made up of individual transposable elements inserted into the satellite DNA (48, 67). Similarly, in human cells the alphoid satellite repeat, a 171-bp repeat found in many centromere regions, was used to construct the first human artificial chromosome (26). We have discovered three simple repeats, clustered at the met7-proximal end of the plasmid rescues from the Neurospora LG VII centromere (see Fig. 1C). These three elements are the first simple repeats other than transfer and small rRNA genes that have been reported for the nuclear genome of Neurospora. The first repeat, designated the Tsp repeat for a restriction site found frequently within the sequence, is 56 bp in length and is repeated 4.5 times within this cluster. The DNA sequence and arrangement of the repeats in relation to each other are shown in Fig. 7A. Next in order are 45 iterations of an imperfect TTA microsatellite. The third element, named the Sma repeat for the presence of multiple SmaI sites within each subunit, is 58 bp in length and is present in 3.5 copies. In addition, it is quite G+C- rich, unlike any other sequences found so far in this region, and has the potential to form stem-loop structures due to internal inverted repeats within the 58-bp unit. Southern blots of Neurospora genomic DNA reveal that the Tsp and Sma repeats are present in multiple copies within the genome but are frequently on different restriction fragments (Fig. 7B). A Sma repeat probe hybridizes to relatively few small restriction fragments (<3 kb) in AseI or SspI digests, restriction enzymes with all A+T recognition sequences, but also appears to hybridize to several additional unresolved bands at the top of the lanes on the autoradiograph. This suggests that the repeat may be located primarily in regions of the genome enriched for G+C nucleotides. The Tsp repeat is also repeated in the genome but perhaps at a lower copy number. Results from probing the same Southern blot with a DNA fragment containing all three repeated elements suggest that the TTA microsatellite also is repeated within the genome, since new bands, unseen in either of the two previous probings, are observed (data not shown).

None of the three repeats appear to be transcribed, since no specific labeled bands can be observed even after overexposure of Northern blots probed with a fragment containing all three repeat elements (data not shown). DNA segments containing the Sma and Tsp repeats show strong and specific fragment mobility shifts when incubated with crude Neurospora protein extracts (22a). It is likely that these sequences play a structural role, and the protein-DNA complexes may be important for processes involved in replication or segregation of the chromosomes.

The remains of a Ty3-like element located between the Tcen and simple repeat regions.

The location of a third new putative transposon (Tgl2) is also shown in Fig. 1C. This element, like the Tgl1 fragment, appears to be a fragment of a gypsy-like element based on sequence similarity to the Ty3-2 transposon of yeast. Blastx searches with DNA sequences occurring between the Tcen element and the three simple repeats yielded significant matches with the pol region of several gypsy-like transposons, with Ty3-2 giving the most significant P value (10−8). Assuming that Tcen had been transposed into the Tgl1 element in the past, a possible fourth fragment of the Tgl1 element would be predicted to be present in this region, located just upstream of the 5′ target site duplication of Tcen but in the opposite orientation. However, the new Ty3-like element appears to be different from the predicted fourth part of the Tgl1 element discussed above. The location (near the simple repeat region), the orientation (in the same direction as the Tcen element), and the lack of sequence similarity of the reverse transcriptase regions suggest that Tgl1 and the new Ty3 like element are in fact two different gypsy-like elements. The absence of other examples of this element for comparison, and the degeneracy of the sequence, prevented us from discerning the exact borders of this potential transposon, tentatively designated Tgl2.

DISCUSSION

Genome size and repeat content of the Neurospora genome.

The genome DNA content of Neurospora has been variously estimated to be from 27 Mb (36) to a more likely value of ∼45 Mb (51). Krumlauf and Marzluf (36) reported that the amount of repetitive DNA, based on reassociation kinetics, constituted only 8% of the genome and suggested that known repeats such as ribosomal DNA (rDNA) genes could account for nearly all of this repetitive DNA. Using methods to estimate the length and interspersion of the repeats, these authors also found that the repetitive fraction is in large, contiguous stretches of 73 kb or larger. They suggested that the tandemly repeated rDNA array itself might account for 5 to 6% of the genome, depending on the number of iterations of the unit ribosomal repeat (and the accuracy of their genome size estimate). It is now generally accepted that the genome is nearly twice as large as previously thought. Given the number of the rDNA repeats, they are not likely to account for the bulk of the repeated DNA (5, 74). In this work, we have elucidated the structure of a portion of the centromere region of Neurospora LG VII and have found that this region is made up of tightly nested repeated DNA elements. Our Southern blot data using just two species of repeats shows multiple clusters within the LG VII centromere region and suggests that the centromere may indeed be a contiguous set of transposon-like and simple sequence repeats. The high degree of degeneracy of the repeated sequences present in this region (probably due to RIP) may have led to an artificially low estimate of repeated sequences in general, since many interactions between homologous (vertically related) sequences may not be observed in solution hybridizations, dependent upon the conditions. Assuming that all seven centromere regions are of a size similar to that of the LG VII region (0.45 Mb), repeated centromeric DNA might make up as much as 3.2 Mb of the total. Correspondingly, ∼7% of all the YACs in the Centola YAC library of Neurospora genomic DNAs hybridize with Tcen (centromere-specific) probes (10), also giving an estimate of ∼3.2 Mb of centromeric DNA, assuming that the identified YACs are entirely repeated DNA and that the genome size is ∼45 Mb.

Homology searches in RIP and recombination are mechanistically different.

The pronounced divergence that is observed in these repeated sequences is suggestive of the RIP system, a process that involves a homology-dependent search mechanism followed by a dramatic mutagenesis of the repeated DNA (8, 61). An important conclusion from this work is that despite the fact that the 450-kb region between the qa gene cluster and met7 undergoes very little meiotic recombination (10) sequences that reside there are not immune to RIP. Furthermore, this observation suggests that if a particular chromatin conformation is responsible for the unique properties of centric heterochromatin, then this conformation must be differentially accessible to proteins involved in recombinational versus RIP processes. Alternatively, centromere properties might be the result of localization differences within the nucleus (31). In this case, the apparently differing effects of these two homology search-based processes could be the result of temporal or physical differences in the compartmentalization of the participating enzymes. It is possible, however, that the relative frequency of RIP might also be dramatically lower for targets in centromeres and that the high level of divergence is simply the result of the extended time since the tranposition events occurred. The effect of centromere location on the propensity of duplicated sequences to undergo RIP has not been investigated.

Cryptic transposons may destabilize Neurospora chromosomes.

Our observation that dTad elements reside not only in centromeric locations but also at a subtelomeric site and at various other sites in the genome has implications for genome dynamics and the behavior of unstable partial diploids in Neurospora. Partial diploids that result from quasiterminal translocations and subsequent crossing into normal sequence strains typically lead to degradation of the partial diploid into mixed haploid and diploid heterokaryons (53, 54). Newmeyer and Galeazzi (49) demonstrated that for one very unstable partial diploid the translocated segment is usually deleted to restore the haploid sequence, and they proposed that the initial translocation and the resolution event were the result of homologous recombination events between repeated DNAs located at the chromosome tip and the translocation breakpoint. As more dTads (and other degenerate transposons) are discovered and mapped it will be interesting to correlate the presence of these elements with the known translocation endpoints in various strains producing unstable diploids. Alternatively, it may be feasible to look directly in these strains for sequence polymorphisms that map to the breakpoints by using dTad probes at a low-hybridization stringency.

Tcen elements and centromere function.

The significance of the centromere-specific localization of the Tcen element is unclear. It is possible that Tcen had exquisitely particular sequence and/or chromatin structural requirements for sites of integration. The presence of typical 5-bp TSDs does not distinguish this element from the Ty families of S. cerevisiae, where integration shows some preference but generally occurs throughout the genome (4, 16, 75). An alternative hypothesis is that Tcen integration into genic regions is relatively deleterious and thus selection strongly alters the population structure in favor of only centromeric integrants. The presence of other large insertion elements such as Tad in the intergenic regions of Neurospora would seem to argue against this possibility but it is unclear what affect on fitness these insertions have. It is clear, however, that low levels of Ty integration into genic regions of budding yeast can have positive effects in long-term population studies (72).

Another potential mechanism for the skewed localization of Tcen might involve ectopic recombination between similar Tcen elements at unlinked loci. Translocations and other chromosomal abnormalities would be the predicted result of these events and might affect population structure if they imposed severe negative selection (12). Regions of low recombination, such as centromeres, would be less likely to participate in these events. Interestingly, wild isolates of Neurospora have shown no evidence of such abnormalities, unlike the genomes of related fungi that display considerable genome plasticity (see reference 53 and references therein). It seems unlikely that selection is the only force responsible for the stability of the Neurospora genome since it would require that all classes of gross aberrations be strongly selected against and does not explain the differences in karyotype stability among similar fungi. The effect of RIP on repeated sequences might help explain this difference if degeneration of sequence homology has a dampening effect on ectopic recombination which is similar to that on intrachromosomal recombination between tandem repeats (9, 30, 60).

Finally, it seems possible that Tcen is a very ancient element that long ago was co-opted by the cell to serve a centromere function, perhaps to initiate heterochromatin formation in this specialized region of the genome. Three observations support this possibility. (i) Recent analysis of the human centromere-specific protein CENP-B and homologs from S. pombe (Abp1 and Cbh1) suggest descent of these proteins from transposases (24, 65). (ii) It has been shown that in Drosophila, repeated copies of P-element insertions are sufficient for initiation of chromatin structures that are functionally equivalent to heterochromatin (18). (iii) Repeated elements in the S. pombe centromere that are essential for cen function (K elements) are structurally similar to LTR transposons but do not code for proteins. These observations, taken together with the unique localization of Tcen, may suggest a role for this sequence in the formation of the Neurospora centromere. Further experiments will be required to distinguish these various possibilities.

The overall picture now emerging of the structure of Neurospora centromeres suggests that this organism, like the fly and vertebrates, has a regional, complex centromere. The potential for use of this genetically well-developed haploid system in studies on the mechanism of centromere formation and heterochromatin-associated epigenetic regulatory phenomena seems very high indeed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of Louise Clarke’s lab for helpful discussion and J. A. Kinsey and S. Myers for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (GM17371) to E.B.C. and an NIH grant (CA-11034) to J.C., who is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allshire R C. Centromeres, checkpoints and chromatid cohesion. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:264–273. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allshire R C, Karpen G H. The case for epigenetic effects on centromere identity and function. Trends Genet. 1997;13:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeke J D. Transposable elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1989. pp. 335–374. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks R R, Huang P C. Redundant DNA of Neurospora crassa. Biochem Genet. 1972;6:41–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00485964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown W, Tyler-Smith C. Centromere activation. Trends Genet. 1995;11:337–339. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cambareri E B, Helber J H, Kinsey J A. Tad 1-1, an active LINE-like element of N. crassa. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:658–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00283420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cambareri E B, Jensen B C, Schabtach E, Selker E U. Repeat-induced G-C to A-T mutations in Neurospora. Science. 1989;244:1571–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.2544994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cambareri E B, Singer M J, Selker E U. Recurrence of repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) in Neurospora crassa. Genetics. 1991;127:699–710. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.4.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centola M, Carbon J. Cloning and characterization of centromeric DNA from Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1510–1519. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centola M B. Ph.D. thesis. Santa Barbara: University of California; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. The population dynamics of transposable elements. Genet Res. 1983;42:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlesworth B, Sniegowski P, Stephan W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature. 1994;37:215–220. doi: 10.1038/371215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danilevskaya O, Slot F, Pavlova M, Pardue M L. Structure of the Drosophila HeT-A transposon: a retrotransposon-like element forming telomeres. Chromosoma. 1994;103:215–224. doi: 10.1007/BF00368015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis R H, DeSerres F J. Genetic and microbial research techniques for Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol. 1970;17A:47–143. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devine S E, Boeke J D. Integration of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 is targeted to regions upstream of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III. Genes Dev. 1996;10:620–633. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobinson K F, Harris R E, Hamer J E. Grasshopper, a long terminal repeat (LTR) retroelement in the phytopathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:114–126. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-6-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorer D R, Henikoff S. Expansions of transgene repeats cause heterochromatin formation and gene silencing in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;77:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuSarte D, Cancilla M R, Earle E, Mao J I, Saffery R, Tainton K M, Kalitsis P, Martyn J, Barry A E, Choo K H. A functional neocentromere formed through activation of a latent human centromere consisting of non-alpha-satellite DNA. Nat Genet. 1997;16:144–153. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farman M L, Tosa Y, Nitta N, Leong S A. MAGGY, a retrotransposon in the genome of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:665–674. doi: 10.1007/BF02174115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grandbastien M-A, Spielmann A, Caboche M. Tnt1, a mobile retroviral-like transposable element of tobacco isolated by plant cell genetics. Nature. 1989;337:376–380. doi: 10.1038/337376a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grayburn W S, Selker E U. A natural case of RIP: degeneration of the DNA sequence in an ancestral tandem duplication. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4416–4421. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Gutkin, G., and E. Cambareri. Unpublished results.

- 23.Haaf T, Warburton P E, Willard H F. Integration of human alpha-satellite DNA into simian chromosomes: centromere protein binding and disruption of normal chromosome segregation. Cell. 1992;70:681–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90436-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halverson D, Baum M, Stryker J, Carbon J, Clarke L. A centromere DNA-binding protein from fission yeast affects chromosome segregation and has homology to human CENP-B. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:487–500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen L J, Chalker D L, Sandmeyer S B. Ty3, a yeast retrotransposon associated with tRNA genes, has homology to animal retroviruses. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5245–5256. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrington J J, VanBokkelen G, Mays R W, Gustashaw K, Willard H F. Formation of de novo centromeres and construction of first-generation human artificial microchromosomes. Nat Genet. 1997;15:345–355. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoogland C, Biemont C. Chromosomal distribution of transposable elements in Drosophila melanogaster: test of the ectopic recombination model for maintenance of insertion site number. Genetics. 1996;144:197–204. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson C A, III, Hardies S C, Loeb D D, Shehee W R, Edgell M H. LINEs and related retrotransposons: long interspersed repeated sequences in the eucaryotic genome. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 593–617. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irelan J T, Hagemann A T, Selker E U. High frequency repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) is not associated with efficient recombination in Neurospora. Genetics. 1994;138:1093–1103. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karpen G H. Position-effect variegation and the new biology of heterochromatin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karpen G H, Le M H, Le H. Centric heterochromatin and the efficiency of achiasmate disjunction in Drosophila female meiosis. Science. 1997;273:118–122. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinsey J A. Restricted distribution of the Tad transposon in strains of Neurospora. Curr Genet. 1989;15:271–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00447042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Kinsey, J. A. Personal communication.

- 34.Kinsey J A, Garrett-Engele P W, Cambareri E B, Selker E U. The Neurospora transposon Tad is sensitive to repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) Genetics. 1995;138:657–664. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinsey J A, Helber J. Isolation of a transposable element from Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1929–1933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krumlauf R, Marzluf G A. Characterization of the sequence complexity and organization of the Neurospora crassa genome. Biochemistry. 1979;18:3705–3713. doi: 10.1021/bi00584a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le M H, Duricka D, Karpen G H. Islands of complex DNA are widespread in Drosophila centric heterochromatin. Genetics. 1995;141:283–303. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindauer A, Fraser D, Bruderlein M, Schmitt R. Reverse transcriptase families and a copia-like retrotransposon, Osser, in the green alga Volvox carteri. FEBS Lett. 1993;319:261–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80559-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lohe A R, Hilliker A J, Roberts P A. Mapping simple repeated DNA sequences in heterochromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1993;134:1149–1174. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lohe A R, Brutlag D L. Multiplicity of satellite DNA sequences in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:696–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manninen I, Schulam A H. BARE-1, a copia-like retroelement in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:829–846. doi: 10.1007/BF00027369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mason J M, Biessmann H. The unusual telomeres of Drosophila. Trends Genet. 1995;11:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)88998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McClintock B. Neurospora. I. Preliminary observations of the chromosomes of Neurospora crassa. Am J Bot. 1945;32:671–678. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzenberg R L, Stevens J N, Selker E, Morzycka-Wroblewska E. A method for finding the genetic map position of cloned DNA fragments. Neurospora Newsl. 1984;31:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell A R, Gosden J R, Miller D A. A cloned sequence, p82H, of the alphoid repeated DNA family found at the centromeres of all human chromosomes. Chromosoma. 1985;92:369–377. doi: 10.1007/BF00327469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullis K B, Faloona F A. Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy T D, Karpen G H. Localization of centromere function in a Drosophila minichromosome. Cell. 1995;82:599–604. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newmeyer D, Galeazzi D R. The instability of Neurospora duplication Dp(IL;IR)H4250, and its genetic control. Genetics. 1977;85:461–487. doi: 10.1093/genetics/85.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orbach M J. A cosmid with a HyR marker for fungal library construction and screening. Gene. 1994;150:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90877-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orbach M J, Vollrath D, Davis R W, Yanofsky C. An electrophoretic karyotype of Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1469–1473. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perkins D D. Chromosome rearrangements in Neurospora and other filamentous fungi. Adv Genet. 1997;36:239–398. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perkins D D, Barry E G. The cytogenetics of Neurospora. Adv Genet. 1977;19:133–285. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pluta A F, Mackay A M, Ainsztein A M, Goldberg I G, Earnshaw W C. The centromere: hub of chromosomal activities. Science. 1995;270:1591–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rhodes M M. P. 66–80. In: Gowen J W, editor. Heterosis. Ames: Iowa State Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schechtman M. Isolation of telomere DNA from Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3168–3177. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schechtman M G. Characterization of telomere DNA from Neurospora crassa. Gene. 1990;88:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90027-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Selker E, Cambareri E, Jensen B, Haack K. Rearrangement of duplicated DNA in specialized cells of Neurospora. Cell. 1987;51:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selker E U. Premeiotic instability of repeated sequences in Neurospora crassa. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:579–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selker E U, Jensen B C, Richardsen G A. A portable signal causing faithful DNA methylation de novo in Neurospora crassa. Science. 1987;238:48–53. doi: 10.1126/science.2958937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherman F, Fink G R, Hicks J B. A laboratory course manual for methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singleton J R. Chromosome morphology and the chromosome cycle in the ascus of Neurospora crassa. Am J Bot. 1953;40:124–144. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smit A F, Riggs A D. Tiggers and other transposon fossils in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1443–1448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steiner N C, Clarke L. A novel epigenetic effect can alter centromere function in fission yeast. Cell. 1994;79:865–874. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun X, Wahlstrom J, Karpen G. Molecular structure of a functional Drosophila centromere. Cell. 1997;91:1007–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80491-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tyler-Smith C, Oakey R J, Larin Z, Fisher R B, Crocker M, Affara N A, Ferguson-Smith M A, Muenke M, Zuffardi O, Jobling M A. Localization of DNA sequences required for human centromere function through an analysis of rearranged Y chromosomes. Nat Genet. 1993;5:368–375. doi: 10.1038/ng1293-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wandall A. Clonal origin of partially inactivated centromeres in a stable dicentric chromosome. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1995;69:193–195. doi: 10.1159/000133961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wellinger R J, Sen D. The DNA structures at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:735–749. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilbur W J, Lipman D J. Rapid similarity searches of nucleic acid and protein data banks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;80:726–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilke C M, Maimer E, Adams J. The population biology and evolutionary significance of Ty elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetica. 1992;86:155–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00133718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams B C, Murphy T D, Goldberg M L, Karpen G H. Neocentromere activity of structurally acentric minichromosomes in Drosophila. Nat Genet. 1997;18:30–37. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wood D D, Luck D J L. Hybridization of mitochondrial ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou S, Ke N, Kim J M, Voytas D F. The Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5 integrates preferentially into regions of silent chromatin at the telomeres and mating loci. Genes Dev. 1996;10:634–645. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zinkowski R P, Meyne J, Brinkley B R. The centromere-kinetochore complex: a repeat subunit model. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1091–1110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]