Abstract

Objectives.

(1) Explore the characteristics of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) maintained on either methadone or buprenorphine and (2) determine the relative acceptability of integrating Tai Chi (TC) practice into an ongoing medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder (MOUD) program.

Design.

Survey study

Setting:

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Center for Addiction Services and Treatment Program.

Patients:

97 patients receiving MOUD treatment.

Main Outcomes.

Drug use history, treatment status, physical limitation, mental health, pain, and whether participants were interested in using TC to improve health outcomes.

Results.

At least 30.9% of the sample reported moderate or higher level of limitation in performing rigorous physical activities, pain intensity and pain interference. Between 37.1% and 61.5% of the sample reported various psychiatric symptoms. Methadone patients reported higher levels of physical limitations, especially in rigorous activities (p=.012), climbing several flights of stairs (p=.001), and walking more than a mile (p=.011), but similar levels of pain (ps=.664–.689) and psychiatric symptoms (ps=.262–.879) relative to buprenorphine patients. At least 40.2% of participants expressed moderate or higher level of interest in TC for improving health outcomes, with methadone patients more interested in participating to ease mental and sleep problems (p=.005) and improve physical fitness (p=.015) compared to buprenorphine patients.

Conclusions.

High prevalence of physical limitation, pain and psychiatric comorbidities were found in OUD patients. Since patients were interested in TC to improve their health outcomes, this low-cost intervention, if proven effective, can be integrated into ongoing MOUD programs to improve health in this population.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, medication-assisted therapy, Tai Chi, pain, physical limitations, psychiatric symptoms

Introduction

The opioid crisis is a public health emergency in the United States. An estimated 2.7 million people in the US suffered from opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2020,1 with OUD-associated medical costs estimated at $1.02 trillion.2,3 Serious consequences of OUD include fatal overdoses, with an estimated 21.7 overdose deaths per 100,000 people in 2017 (up from 6.1 in 1999)4 Medication-assisted therapy is often recommended for OUD (MOUD), with methadone and buprenorphine being the most commonly used agents.5–7 However, treatment retention tends to be poor and continued opioid use and/or relapse rates remain high.8–10

Chronic pain, psychiatric problems, and poor physical health are common comorbid conditions in patients with OUD,11–18 with more than 60% reporting chronic pain and/or psychiatric problems.11–14,19–24 Having an OUD diagnosis also predicts worse physical health relative to those without OUD.21 Although MOUD has positive effects on these coexisting health conditions, results are inconsistent23 and untreated pain, psychiatric and physical comorbidities increase the risk of poor retention in MOUD treatment and continued opioid use and/or relapse.8,25–36

With a call for non-pharmacological interventions as a component of an overall treatment strategy for pain care,37 exercise such as Tai Chi (TC), a gentle exercise with continuous, slow, fluid movements, may be an effective adjunct therapy to improve retention and reduce risk of continued opioid use or relapse among MOUD patients. This rationale is supported by several lines of evidence. Exercise studies generally show beneficial effects for psychiatric problems and/or physical health in various substance use disorder groups.38–41 Additionally, mild exercise, such as yoga or TC, improves chronic pain, psychiatric symptoms, and physical health in OUD or amphetamine use disorder patients undergoing detoxification.42–45 Specifically, TC has been used as an alternative therapy for relieving pain.46–52 For patients with OUD who suffer from arthritis and leg pain,12,53,54 TC may offer a better option than yoga because some yoga poses may cause pain, which may deter participation. Importantly, TC is suitable for sedentary populations, as only 23% of methadone patients meet the recommended exercise levels.55 To our knowledge, no major study examining the effect of TC on chronic pain, psychiatric problems, and physical health has been conducted to date in patients with OUD undergoing MOUD. Given that TC practice and preference may depend on patients’ characteristics, the aim of this study was to (1) explore the characteristics of OUD patients maintained on either methadone or buprenorphine and (2) determine the relative acceptability of integrating TC practice into an ongoing MOUD program.

Method

Study Population and Setting

Patients receiving MOUD through the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Center for Addiction Services and Treatment (CAST) Program were recruited to participate in this study. The only eligibility criterion was that participants are currently receiving MOUD in the program. All participants were 18 or older.

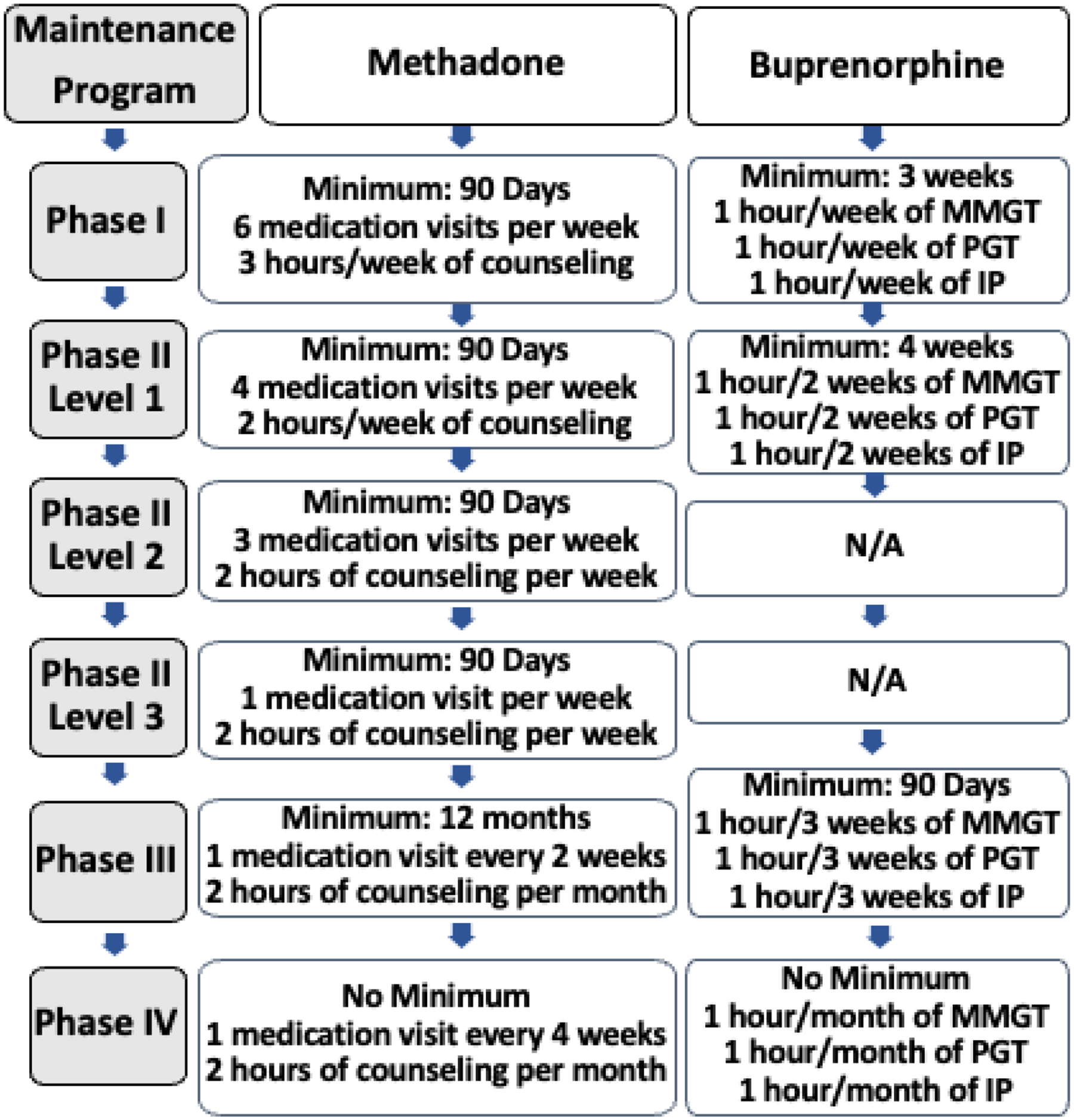

The CAST program treatment protocol consists of several phases, depending on treatment compliance and response, that differ between buprenorphine and methadone programs. The CAST methadone program treatment protocol follows state and federal regulations and consists of four phases (see Figure 1 for details). In order to move from Phase I to Phase II Level 1, patients need to have weekly urine samples negative for drugs and alcohol for the last 30 days, have attended all required clinic and counseling appointments, have no serious behavioral problems at the clinic or known criminal activity within the last 30 days, have a stabilized home environment and social relationships, and assured safe storage of take-home medications. Patients can move to Phase II Level 2 if their urine samples are negative for drugs or alcohol for the past 90 days and they are compliant with program requirements, as in Phase 1. Patients can move to Phase II Level 3 as long as they continue to have negative urine screens and adhere to treatment protocol requirements for at least 90 additional days. Similarly, patients continuing to have negative urine screens and adhere to treatment protocol requirements for at least 90 days while in Phase II level 3 are eligible to advance to Phase III. If they have negative drug screens and attend all individual and group counseling sessions during 12 month period, they are eligible to advance to Phase IV.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram of CAST treatment phases. MMGT: Medication Management Group Therapy; PGT: Psychoeducation Group Therapy; IP: Individual Psychotherapy.

The CAST Suboxone/buprenorphine program offers four phases of treatment (See Figure 1 for details). During Phase I, patients provide weekly urine samples. A Phase I patient can enter Phase II as long as they attend all group/individual appointments and have drug-negative urine results over a three-consecutive-week period. If urine samples continue to be negative and all appointments are attended over a four- week period, a patient enters Phase III. If a patient continues to be treatment/program compliant for a total of three months from treatment entry, they enter Phase IV.

Study Design and Procedures

The UAMS Institutional Review Board approved this study as an exempt protocol. CAST group facilitators distributed the anonymous survey at the beginning of their regular group therapy sessions. The introductory paragraph of the survey was read aloud by the group facilitator. If patients decided to complete the survey, they were considered to have consented to participate. Patients had the choice not to fill out the survey. Approximately 10 minutes were devoted to having participants complete the survey. The group facilitator collected the completed surveys, placed them in a sealed envelope and gave them to a research staff member. Research staff assigned a unique study ID code to each survey form, entered the data into excel using a double-entry procedure, and used a compare function to determine and resolve any inconsistencies between the two datasets before data analysis.

Measurement Tool

The investigator-designed survey collected data on participant demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, and education), drug use history (e.g., primary opioid of abuse before program entry and duration of the use), treatment status (duration in the current treatment program, MOUD medication, and treatment phase), their physical function, pain, sleep, and other health outcomes, and whether participants were interested in using TC to improve these outcomes.

The 10-item physical function scale questions were the same as the Physical Function Scale (Items 3–12) on the SF 36 Short Form Survey Instrument56 but rated on a six-point scale, with 0 indicating not at all difficult and 5 indicating extremely difficult. Similarly, the two-item pain intensity and pain interference scale had the same questions as the Pain scales (Item 21–22) on the SF 36 Short Form56 but rated on a six-point scale, with 0 indicating no level of pain or interference and 5 indicating extreme level of pain or interference. These modifications were made to complement another survey being performed with CAST patients to measure common opioid-induced medication side effects, such as anxiety, nervousness, constipation, restlessness, sleep problems, depression, stress and lack of energy.57,58

The final set of questions asked participants if they were interested in a TC program for specifically targeted health benefits. This set included four questions asking participants if they were interested in participating in a TC program that eases their mental health (anxiety, nervousness, restlessness, depression, stress and lack of energy), eases sleep problems, eases pain, and improves their physical fitness, rated on a six-item Likert scale from 0, indicating not at all interested, to 5, indicating extremely interested. These question sets are included in the appendix.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., means ± standard deviation; percentages) were used to describe the characteristics for the total sample. The two treatment groups (methadone and buprenorphine) were compared on normally distributed variables with two-sample t-tests, on other continuous variables with Mann-Whitney tests, and on categorical variables with chi-square tests.

Results

Table 1 shows participant characteristics. Participants (N=97) were aged 38.58 (±11.82) years on average; 55.7% were male and 85.4% Caucasian. The top five opioids abused prior to treatment were Oxycontin (34.4%), Heroin (25%), Hydrocodone (24%), Percocet (18.8%) and Fentanyl (16.7%); some participants abused more than one type of opioid. On average, they have been in the current treatment program for 2.05 (±2.92) years. Overall, 34.8% of respondents lived with a significant other or were married; however, methadone patients were more likely to be separated or divorced (25.6% vs. 8.9%) and less likely to be living together with someone or married (25.6% vs. 41.1%) than respondents receiving buprenorphine treatment. The majority (66.7%) of methadone patients were in Phase I of treatment, whereas the majority of buprenorphine patients were in Phase III (33.9%) or IV (30.4%).

Table 1.

Participant demographics and baseline characteristics.

| Total (n=97) | Methadone (n=40) | Buprenorphine (n=57) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 38.58 (11.82) | 40.95 (12.24) | 36.91 (11.33) | .098 |

| Male gender | 55.7% | 50% | 59.6% | .463 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 85.4% | 86.8% | 87.5% | .704 |

| African American | 8.3% | 10.5% | 7.1% | |

| Other races | 6.3% | 2.6% | 5.4% | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 46.3% | 43.6% | 48.2% | .012 |

| Living together | 7.4% | 12.8% | 3.6% | |

| Married | 27.4% | 12.8% | 37.5% | |

| Separated/divorced | 15.8% | 25.6% | 8.9% | |

| Widowed | 3.2% | 5.1% | 1.8% | |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High school | 35.8% | 34.2% | 36.8% | .965 |

| > High school | 64.2% | 65.8% | 63.2% | |

| Drug abuse history | ||||

| Main opioid of abuse prior to treatment | ||||

| Oxycodone | 34.4% | 32.5% | 35.7% | |

| Heroin | 25.0% | 32.5% | 19.6% | |

| Hydrocodone | 24.0% | 17.5% | 28.6% | |

| Percocet | 18.8% | 15.0% | 21.4% | |

| Fentanyl | 16.7% | 20.0% | 14.3% | |

| Dilaudid | 10.4% | 10.0% | 10.7% | |

| Oxycontin | 10.4% | 10.0% | 10.7% | |

| Opana | 8.2% | 12.5% | 5.4% | |

| Morphine | 7.3% | 12.5% | 3.6% | |

| Vicodin | 6.3% | 7.5% | 5.4% | |

| Methadone | 5.2% | 5.0% | 5.4% | |

| Buprenorphine | 3.1% | 0% | 5.4% | |

| Duration of abuse prior to treatment (Years) | 9.76 (8.38) | 11.69 (8.64) | 8.41 (8.00) | .058 |

| Duration of current treatment (Years) | 2.05 (2.92) | 2.53 (3.93) | 1.71 (1.88) | .224 |

| Phase of treatment | ||||

| Phase 1 | 43.2% | 66.7% | 26.8% | .000 |

| Phase 2 | 12.6% | 17.9% | 8.9% | |

| Phase 3 | 24.2% | 10.3% | 33.9% | |

| Phase 4 | 20.0% | 5.1% | 30.4% | |

| Physical limitation | ||||

| Vigorous activities | 2.05 (1.84) | 2.55 (1.78) | 1.70 (1.81) | .012 |

| ≥ Moderate | 42.3% | 50.0% | 36.8% | .279 |

| Moderate activities | 1.05 (1.38) | 1.20 (1.29) | .95 (1.44) | .222 |

| ≥ Moderate | 22.7% | 27.5% | 19.3% | .482 |

| Lifting/carrying groceries | .77 (1.14) | .95 (1.09) | .65 (1.17) | .061 |

| ≥ Moderate | 11.3% | 12.5% | 10.5% | .757 |

| Climbing several flights of stairs | 1.54 (1.61) | 2.05 (1.43) | 1.19 (1.64) | .001 |

| ≥ Moderate | 31.3% | 41.0% | 24.6% | .138 |

| Climbing one flight of stairs | .84 (1.28) | 1.05 (1.24) | .70 (1.29) | .037 |

| ≥ Moderate | 13.5% | 15.0% | 12.5% | .960 |

| Bending, kneeling, or stooping | 1.20 (1.45) | 1.43 (1.36) | 1.04 (1.50) | .044 |

| ≥ Moderate | 20.8% | 20.0% | 21.4% | 1.000 |

| Walking more than a mile | 1.58 (1.73) | 2.03 (1.63) | 1.26 (1.75) | .011 |

| ≥ Moderate | 28.9% | 37.5% | 22.8% | .179 |

| Walking half a mile | 1.16 (1.63) | 1.45 (1.58) | .96 (1.64) | .046 |

| ≥ Moderate | 19.6% | 25.0% | 15.8% | .387 |

| Walking 100 yards | .68 (1.21) | .78 (1.17) | .61 (1.25) | .141 |

| ≥ Moderate | 11.3% | 10.0% | 12.3% | 1.000 |

| Bathing and dressing yourself | .52 (1.06) | .69 (1.15) | .39 (.99) | .056 |

| ≥ Moderate | 4.2% | 5.1% | 3.6% | 1.000 |

| Pain and interference last week | ||||

| Pain intensity | 2.35 (1.48) | 2.40 (1.45) | 2.32 (1.51) | .689 |

| ≥ Moderate | 49.5% | 52.5% | 47.4% | .771 |

| Pain interference | 1.87 (1.56) | 1.93 (1.49) | 1.82 (1.62) | .664 |

| ≥ Moderate | 30.9% | 30.0% | 31.6% | 1.000 |

| Mental Health | ||||

| Stress | 3.01 (1.29) | 2.85 (1.18) | 3.12 (1.35) | .302 |

| ≥ Moderate | 61.5% | 61.5% | 61.4% | 1.000 |

| Lack of energy | 2.90 (1.54) | 2.85 (1.55) | 2.93 (1.56) | .794 |

| ≥ Moderate | 57.7% | 55.0% | 59.6% | .805 |

| Anxiety | 2.86 (1.44) | 2.78 (1.27) | 2.91 (1.56) | .619 |

| ≥ Moderate | 56.7% | 55.0% | 57.9% | .940 |

| Sleep problems | 2.55 (1.59) | 2.78 (1.53) | 2.39 (1.63) | .262 |

| ≥ Moderate | 49.5% | 50.0% | 49.1% | 1.000 |

| Nervousness | 2.49 (1.38) | 2.58 (1.26) | 2.43 (1.48) | .477 |

| ≥ Moderate | 47.9% | 52.5% | 44.6% | .581 |

| Restlessness | 2.43 (1.38) | 2.40 (1.26) | 2.45 (1.48) | .879 |

| ≥ Moderate | 42.7% | 37.5% | 46.4% | .508 |

| Depression | 2.19 (1.45) | 2.30 (1.45) | 2.11 (1.45) | .481 |

| ≥ Moderate | 37.1% | 37.5% | 36.8% | 1.000 |

In terms of physical functioning, methadone patients had higher levels of limitation than buprenorphine patients when performing the following activities: vigorous activities (p=.012), climbing several flights of stairs (p=.001), climbing one flight of stairs (p=.037), bending, kneeling or stooping (p=.044), and walking more than a mile (p=.011); see Table 1. When examining participants who experienced at least moderate limitations in physical functioning regardless of MOUD medication, the top three limited activities for the total sample were vigorous activities (42.3%), climbing several flights of stairs (31.3%), and walking more than a mile (28.9%). No medication group differences were observed regarding the proportion of patients experiencing at least moderate levels of limitation for any of the physical functioning variables (ps=.138–1.00) (Table 1).

Methadone and buprenorphine groups reported similar levels of pain intensity (2.40 vs 2.32) and pain interference (1.93 vs 1.82). Table 1 shows that nearly half of all participants experienced moderate or greater levels of pain intensity (49.5%) and about a third of the total sample reported that pain interfered with their normal daily activities (30.9%). No significant medication group differences in the proportion of participants experiencing at least moderate pain intensity (p=.771) or pain interference (p=1.000) were found.

Medication groups reported similar levels of anxiety, nervousness, restlessness, depression, stress and lack of energy (ps=.262–.879) (Table 1). A higher percentage of participants reported at least moderate severity of psychiatric problems compared to physical functioning and pain. Approximately 61.5% of all participants experienced moderate or higher severity of stress, followed by lack of energy (57.7%), anxiety (56.7%), sleep problems (49.5%), nervousness (47.9%), restlessness (42.7%), and depression (37.1%). The percentage of participants experiencing at least moderate severity of common psychiatric problems was similar across medication groups (ps=.508–1.000).

Interest in participating in a TC program for reducing pain did not significantly differ between the two groups (p=.079) (Table 2). Table 2 also shows that 40.2% of the overall sample were at least moderately interested in participating in a TC program. Improving physical health was chosen by 58.8% of total participants as a reason for participating in TC, followed by easing pain (55.7%), easing sleep problems (49.5%) and easing mental health problems (40.2%). Methadone patients, however, were more interested in participating in a TC program for the purpose of improving physical fitness (p=.015), easing sleep problems (p=.034) and easing mental problems (p=.005) compared to buprenorphine patients. For the total sample, the various reasons for participating in TC were highly correlated (Spearman rho =.763–.797) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Rationales for participants’ interest in Tai Chi

| Interest in Tai Chi for | Total (n=97) | Methadone (n=40) | Buprenorphine (n=57) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improve physical fitness | 2.82 (1.60) | 3.33 (1.42) | 2.47 (1.64) | .015 |

| ≥ Moderate | 58.8% | 62.5% | 56.1% | .677 |

| Ease pain | 2.79 (1.63) | 3.15 (1.58) | 2.54 (1.64) | .079 |

| ≥ Moderate | 55.7% | 60.0% | 52.6% | .609 |

| Ease sleep problems | 2.51 (1.62) | 2.95 (1.50) | 2.19 (1.63) | .034 |

| ≥ Moderate | 49.5% | 55.0% | 45.6% | .482 |

| Ease mental health problems | 2.35 (1.54) | 2.88 (1.47) | 1.98 (1.49) | .005 |

| ≥ Moderate | 40.2% | 52.5% | 31.6% | .063 |

Table 3.

Spearman correlations among reasons of interest in Tai Chi. Total N for each pair of reasons was 97. All six correlations had p < .001.

| Ease sleep problems | Ease pain | Improve physical fitness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ease mental health problems | .777 | .763 | .793 |

| Ease sleep problems | .770 | .797 | |

| Ease pain | .787 |

Discussion

Consistent with prior reports,59 the results of the present study showed that almost half of patients receiving MOUD report at least moderate-level pain. This study also found that pain ratings were high as well as the ratings of psychiatric symptoms compared to physical limitations ratings, except for the rating of vigorous activities. A previous study found that for similar OUD patient populations, the global mental health score was worse than the physical health score,60 and this was confirmed in our findings. At the same time, this study showed a high percentage of moderate and higher levels of symptoms for physical limitation in rigorous activities, pain and mental problems, with mental problems in the following order of intensity: stress, lack of energy, anxiety, sleep problems, nervousness, restlessness and depression. These findings are similar to the results of a multisite randomized controlled trial study.6 These findings highlight the high prevalence of pain and psychiatric comorbidities in OUD patient populations.

When compared between the two medication groups, unlike a prior report,59 methadone patients in the present study reported higher levels of physical limitations, especially in rigorous activities, but similar levels of pain and psychiatric symptoms relative to buprenorphine patients. The reason for the difference in physical limitation between medication groups is unclear and may be due to sampling bias. Alternatively, although not statistically significantly different, there is a trend toward a longer duration of OUD prior to treatment entry for the methadone patients as compared to the buprenorphine-maintained patients, which may be driving the difference in physical limitations.

The rationales and causes for worse mental health are unclear. Potentially, OUD may result in psychiatric symptoms, which leads patients to participate in MOUD therapy. This was evidenced in a European study showing that increased prescription opioid use was significantly related to a higher risk of major depression, anxiety and stress.61 Alternatively, patients may abuse opioids because of their higher level of psychiatric symptoms, which in turn leads to their MOUD therapy. For example, a recent study found that anxiety, anger, and depression are key factors leading to prescribed opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain.60

Medication grouping may be a factor determining what motivates patients’ interest in TC. The current study found that methadone patients were more interested in participating in the TC program to improve physical fitness, and to ease sleep and mental problems compared to buprenorphine patients. Female methadone patients expressed the most enthusiasm for learning TC for physical, sleep, and mental problems, followed by male methadone patients, female buprenorphine patients and male buprenorphine patients (p=.033–.058; data not shown).

Severity of symptoms did not appear to affect patients’ interest in TC exercise. Patients rated physical limitation as the lowest among all symptoms but the overall sample’s highest rated reason for interest in TC was to improve physical limitations. However, this study found that gender differences exist in responses to questions. Female patients’ report of concerns and rationales for interest in TC differed by OUD medication. For example, female methadone patients had the highest rating of interest in TC for mental health, as mentioned earlier, but female buprenorphine patients reported the highest level for mental problems. These findings suggest that gender needs to be considered when prescribing adjunct interventions such as TC.

Interest may also be impacted by the treatment phase patients were in at the time of the survey, with the majority of methadone patients being in Phase I with more frequent visits, while most buprenorphine patients were in Phase III or IV with less frequent visits. Thus, given that most methadone patients were already attending the clinic much more frequently than buprenorphine patients, attending an additional TC class may have been perceived as more convenient for methadone patients who are used to multiple meetings as part of their treatment; and perceived as less convenient for buprenorphine patients whose treatment schedules are less rigorous. This suggests that the timing and burden of additional visits should be considered when researching or implementing adjunct interventions such as TC.

The current study found that patients receiving methadone treatment tend not to be in a relationship as compared to the buprenorphine group. While similar rates of single status are reported by both groups, a significantly higher percentage of methadone patients report separate/divorced status and fewer report living together/married than the buprenorphine group. These differences were mainly observed in males (chi-square [4]=11.25, p=.024, data not shown). Similarly, male methadone patients incurred higher levels of physical limitation for strenuous activities (t[39.7]=1.7, p=.088), climbing several flights of stairs (t[51]=2.08, p=.042), and walking more than a mile (t[52]=2.00, p=.050) than male buprenorphine patients. Female patients, on the other hand, indicated a similar distribution of marital status (chi-square [4]=5.41, p=.247, data not shown) and each of the physical limitations regardless of MOUD. Therefore, the authors postulate that higher levels of physical limitations in the male methadone group associated with (or leading to) OUD result in emotional stress that break down the relationships. A study conducted in a Swedish sample showed that divorce is a risk factor for onset of drug abuse in both genders.62 Unfortunately, this cross-sectional study did not allow determination of causality. Future opioid addiction treatment program research utilizing prospective, randomized, and controlled designs for specific interventions, such as TC, can better evaluate their impact on emotional stress, physical function, and opioid abstinence outcomes. However, gender and relationship status should be considered as covariates when examining outcomes of such research studies.

Limitations of this study include the cross-sectional study design, which did not allow for inferences of causal relationships between various factors and outcomes. Moreover, data were collected from a convenience sample of methadone and buprenorphine patients attending group MOUD therapy during the enrollment period, increasing the risk of sample bias. In addition, this study evaluated participants’ interest in TC, which may not reflect actual participation in a TC intervention. Finally, the measurement tools were modified to accommodate current tools used in the treatment program, which may affect their validity and reliability.

Nevertheless, this project highlights the differences in characteristics between methadone and buprenorphine patients and their interest in adjunct TC. It also provides data necessary to guide a future randomized controlled trial of adjunct TC to improve health outcomes in patients undergoing MOUD. This low-cost group intervention, if proven effective, can be integrated into ongoing MOUD programs to improve health outcomes in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by grant number R01 DA036544 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and, in part, by the Translational Research Institute (TRI), grant TL1 TR003109 through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors wish to thank Ian Fischer Laycock and Vanessa Brill for their assistance with the study and data preparation.

Contributor Information

Pao-Feng Tsai, College of Nursing, Auburn University, 710 South Donahue Drive, Office 3221, Auburn, Alabama 36849-5505.

Alison H. Oliveto, Department of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Reid D. Landes, Department of Biostatistics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Michael J. Mancino, Center for Addiction Services and Treatment, Department of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Substance Abuse Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. June 3, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://nida.nih.gov/download/21349/medications-to-treat-opioid-use-disorder-research-report.pdf?v=99088f7584dac93ddcfa98648065bfbe [Google Scholar]

- 2.Council of Economic Advisers, The Underestimated Cost of the Opioid Crisis, E.O.o.t.P.o.t.U. States, Editor. 2017, Executive Office of the President of the United States: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florence C, Luo F, Rice K. The economic burden of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose in the United States, 2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. Jan 1 2021;218:108350. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(329):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxon AJ, McCance-Katz EF. Some Additional Considerations Regarding the American Society of Addiction Medicine National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med. May–Jun 2016;10(3):140–2. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hser YI, Saxon AJ, Huang D, et al. Treatment retention among patients randomized to buprenorphine/naloxone compared to methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. Jan 2014;109(1):79–87. doi: 10.1111/add.12333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns L, Gisev N, Larney S, et al. A longitudinal comparison of retention in buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid dependence in New South Wales, Australia. Addiction. Apr 2015;110(4):646–55. doi: 10.1111/add.12834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Y, Evans EA, Mooney LJ, et al. Correlates of Long-Term Opioid Abstinence After Randomization to Methadone Versus Buprenorphine/Naloxone in a Multi-Site Trial. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. Dec 2018;13(4):488–497. doi: 10.1007/s11481-018-9801-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine AR, Lundahl LH, Ledgerwood DM, Lisieski M, Rhodes GL, Greenwald MK. Gender-specific predictors of retention and opioid abstinence during methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. Jul 2015;54:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones HE, Terplan M, Meyer M. Medically Assisted Withdrawal (Detoxification): Considering the Mother-Infant Dyad. J Addict Med. Mar/Apr 2017;11(2):90–92. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, Kipnis S, Cleland C, Portenoy RK. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. May 14 2003;289(18):2370–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamison RN, Kauffman J, Katz NP. Characteristics of methadone maintenance patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. Jan 2000;19(1):53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peles E, Schreiber S, Gordon J, Adelson M. Significantly higher methadone dose for methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) patients with chronic pain. Pain. Feb 2005;113(3):340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hser YI, Mooney LJ, Saxon AJ, Miotto K, Bell DS, Huang D. Chronic pain among patients with opioid use disorder: Results from electronic health records data. J Subst Abuse Treat. Jun 2017;77:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, Humphreys K. Response to methadone maintenance treatment of opiate dependent patients with and without significant pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. May 20 2006;82(3):187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins C, Smith BH, Matthews K. Substance misuse in patients who have comorbid chronic pain in a clinical population receiving methadone maintenance therapy for the treatment of opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. Dec 1 2018;193:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis BB, Roshanov PS, Bawor M, et al. Usefulness of the Brief Pain Inventory in Patients with Opioid Addiction Receiving Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Pain Physician. Jan 2016;19(1):E181–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. May 1 2011;34(5):601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brands B, Blake J, Sproule B, Gourlay D, Busto U. Prescription opioid abuse in patients presenting for methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. Feb 7 2004;73(2):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry DT, Savant JD, Beitel M, et al. Pain and associated substance use among opioid dependent individuals seeking office-based treatment with buprenorphine-naloxone: a needs assessment study. Am J Addict. May–Jun 2013;22(3):212–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00327.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhee TG, Rosenheck RA. Association of current and past opioid use disorders with health-related quality of life and employment among US adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. Apr 23 2019;199:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roncero C, Barral C, Rodriguez-Cintas L, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in opioid-dependent patients undergoing a replacement therapy programme in Spain: The PROTEUS study. Psychiatry Res. Sep 30 2016;243:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Crits-Christoph K, Wilber C, Kleber H. Diagnosis and symptoms of depression in opiate addicts. Course and relationship to treatment outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Feb 1982;39(2):151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein MD, Herman DS, Bishop S, et al. Sleep disturbances among methadone maintained patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. Apr 2004;26(3):175–80. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00191-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsui JI, Lira MC, Cheng DM, et al. Chronic pain, craving, and illicit opioid use among patients receiving opioid agonist therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. Sep 1 2016;166:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin ML, McDermott KA, McHugh RK, Fitzmaurice GM, Jamison RN, Weiss RD. Longitudinal association between pain severity and subsequent opioid use in prescription opioid dependent patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. Jun 1 2016;163:216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM treatment of opioid use disorder course. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Accessed May 18, 2019. http://depts.washington.edu/uwconf/nwrhc2018/ASAM_Treatment_of_Opioid_Use.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huhn AS, Sweeney MM, Brooner RK, et al. Prefrontal cortex response to drug cues, craving, and current depressive symptoms are associated with treatment outcomes in methadone-maintained patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. Mar 2019;44(4):826–833. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0252-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong N, Yuan Y, Chen H, et al. Effects of a Randomized Comprehensive Psychosocial Intervention Based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Theory and Motivational Interviewing Techniques for Community Rehabilitation of Patients With Opioid Use Disorders in Shanghai, China. J Addict Med. Jul-Aug 2015;9(4):322–30. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferri M, Finlayson AJ, Wang L, Martin PR. Predictive factors for relapse in patients on buprenorphine maintenance. Am J Addict. Jan-Feb 2014;23(1):62–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12074.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heiwe S, Lonnquist I, Kallmen H. Potential risk factors associated with risk for drop-out and relapse during and following withdrawal of opioid prescription medication. Eur J Pain. Oct 2011;15(9):966–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domino KB, Hornbein TF, Polissar NL, et al. Risk factors for relapse in health care professionals with substance use disorders. JAMA. Mar 23 2005;293(12):1453–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.12.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staedt J, Wassmuth F, Stoppe G, et al. Effects of chronic treatment with methadone and naltrexone on sleep in addicts. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;246(6):305–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark RE, Baxter JD, Aweh G, O’Connell E, Fisher WH, Barton BA. Risk Factors for Relapse and Higher Costs Among Medicaid Members with Opioid Dependence or Abuse: Opioid Agonists, Comorbidities, and Treatment History. J Subst Abuse Treat. Oct 2015;57:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carroll KM, Nich C, Frankforter TL, et al. Accounting for the uncounted: Physical and affective distress in individuals dropping out of oral naltrexone treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. Nov 1 2018;192:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benningfield MM, Dietrich MS, Jones HE, et al. Opioid dependence during pregnancy: relationships of anxiety and depression symptoms to treatment outcomes. Addiction. Nov 2012;107 Suppl 1:74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04041.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. NCCIH Strategic Plan FY 2021–2025. U.S. Department of Health & HUman Services, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementay and Integratuve Health. June 3, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/about/nccih-strategic-plan-2021-2025 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris L, Stander J, Ebrahim W, et al. Effect of exercise versus cognitive behavioural therapy or no intervention on anxiety, depression, fitness and quality of life in adults with previous methamphetamine dependency: a systematic review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. Jan 16 2018;13(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13722-018-0106-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purani H, Friedrichsen S, Allen AM. Sleep quality in cigarette smokers: Associations with smoking-related outcomes and exercise. Addict Behav. Mar 2019;90:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia D, Zhou J, Xu Y. Effectiveness of Traditional Chinese Health-Promoting Exercise as an Adjunct Therapy for Drug Use Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Integr Complement Med. Apr 2022;28(4):294–308. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2021.0285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dowla R, Sinmaz H, Mavros Y, Murnion B, Cayanan E, Rooney K. The Effectiveness of Exercise as an Adjunct Intervention to Improve Quality of Life and Mood in Substance Use Disorder: A Systematic Review. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(6):911–928. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2022.2052098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu D, Dai G, Xu D, et al. Long-Term Effects of Tai Chi Intervention on Sleep and Mental Health of Female Individuals With Dependence on Amphetamine-Type Stimulants. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1476. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li DX, Zhuang XY, Zhang YP, et al. Effects of Tai Chi on the protracted abstinence syndrome: a time trial analysis. Am J Chin Med. 2013;41(1):43–57. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X13500043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhuang SM, An SH, Zhao Y. Yoga effects on mood and quality of life in Chinese women undergoing heroin detoxification: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. Jul-Aug 2013;62(4):260–8. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318292379b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lander L, Chiasson-Downs K, Andrew M, Rader G, Dohar S, Waibogha K. Yoga as an Adjunctive Intervention to Medication-Assisted Treatment with Buprenorphine+Naloxone. J Addict Res Ther. 2018;9(1):354. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai PF, Chang JY, Beck C, Kuo YF, Keefe FJ, Rosengren K. A supplemental report to a randomized cluster trial of a 20-week Sun-style Tai Chi for osteoarthritic knee pain in elders with cognitive impairment. Complement Ther Med. Aug 2015;23(4):570–6. doi:S0965–2299(15)00092–8 [pii] 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai PF, Chang JY, Beck C, Kuo YF, Keefe FJ. A pilot cluster-randomized trial of a 20-week Tai Chi program in elders with cognitive impairment and osteoarthritic knee: effects on pain and other health outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage. Apr 2013;45(4):660–9. doi:S0885–3924(12)00375–2 [pii] 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall AM, Maher CG, Lam P, Ferreira M, Latimer J. Tai chi exercise for treatment of pain and disability in people with persistent low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Nov 2011;63(11):1576–83. doi: 10.1002/acr.20594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brismee JM, Paige RL, Chyu MC, et al. Group and home-based tai chi in elderly subjects with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. Feb 2007;21(2):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song R, Lee EO, Lam P, Bae SC. Effects of a Sun-style Tai Chi exercise on arthritic symptoms, motivation and the performance of health behaviors in women with osteoarthritis. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. Mar 2007;37(2):249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fransen M, Nairn L, Winstanley J, Lam P, Edmonds J. Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or Tai Chi classes. Arthritis Rheum. Apr 15 2007;57(3):407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, et al. Tai Chi is effective in treating knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. Nov 15 2009;61(11):1545–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manubay J, Davidson J, Vosburg S, Jones J, Comer S, Sullivan M. Sex differences among opioid-abusing patients with chronic pain in a clinical trial. J Addict Med. Jan–Feb 2015;9(1):46–52. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Griffin ML, et al. Reasons for opioid use among patients with dependence on prescription opioids: the role of chronic pain. J Subst Abuse Treat. Aug 2014;47(2):140–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beitel M, Stults-Kolehmainen M, Cutter CJ, et al. Physical activity, psychiatric distress, and interest in exercise group participation among individuals seeking methadone maintenance treatment with and without chronic pain. Am J Addict. Mar 2016;25(2):125–31. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. Jun 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc., Subutex (buprenorphine): Highlights of prescribing information. 2011, Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc., Methadone hydrochloride solution; Highlights of prescribing information. 2019, Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunn KE, Finan PH, Tompkins DA, Fingerhood M, Strain EC. Characterizing pain and associated coping strategies in methadone and buprenorphine-maintained patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. Dec 1 2015;157:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilam G, Sturgeon JA, You DS, Wasan AD, Darnall BD, Mackey SC. Negative Affect-Related Factors Have the Strongest Association with Prescription Opioid Misuse in a Cross-Sectional Cohort of Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Med. Feb 1 2020;21(2):e127–e138. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosoff DB, Smith GD, Lohoff FW. Prescription Opioid Use and Risk for Major Depressive Disorder and Anxiety and Stress-Related Disorders: A Multivariable Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. Feb 1 2021;78(2):151–160. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edwards AC, Larsson Lonn S, Sundquist J, Kendler KS, Sundquist K. Associations Between Divorce and Onset of Drug Abuse in a Swedish National Sample. Am J Epidemiol. May 1 2018;187(5):1010–1018. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.