Abstract

Introduction

In the present study the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of Bisphenol-A glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA) was studied on the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ)Bg9.

Materials and methods

The concentration of BisGMA i.e. 0.005, 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M were established in diet and the larvae were allowed to feed on it for 24 h.

Results

A dose dependent significant increase in the activity of β-galactosidase was observed compared to control. A significant dose dependent tissue damage was observed in the larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA compared to control. A dose dependent significant increase in the Oxidative stress markers was observed compared to control. BisGMA also exhibit significant DNA damaged in the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ)Bg9 at the doses of 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M compared to control.

Conclusion

BisGMA at 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M was found to be cytotoxic for the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9.

Keywords: bisphenol-A-glycidylmethacrylate, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, Drosophila, oxidative stress

Introduction

Bowen pioneered the use of dental bonding in 1956. Buonocore was the first to work on enamel preparation techniques, which he did in 1968. Since then, these bonding agents have been used in orthodontics, making multi-banded systems obsolete and bonded appliances the preferred option.1 Dr George Newman, an orthodontist, was the first to bond orthodontic brackets to tooth enamel in the mid-1960s.2 Orthodontic bonding adhesives (OBAs) are used to glue the attachments to the teeth and retain them in position throughout the procedure.3 The majority of practitioners buy commercially available materials with no considerations regarding biocompatibility. While practitioners utilize a variety of orthodontic adhesives today, most research focus on their physical features, such as shear bond strength, with very little attention on biological compatibility.4 Orthodontic adhesives polymerization is never complete (because due to the inhibitory impact of oxygen, polymerization remains incomplete at the surface for an approximate thickness of 10–85 μm) and up to 50% of the components are not involved in the reaction. This indicates that relatively considerable volumes of non-polymerized and potentially hazardous material (up to 14%) could be leaked and responsible for cytotoxic effects.5 Orthodontic adhesives are complex polymers made up of a number of monomers, initiators, activators, stabilizers, plasticizers, and other additives. Bisphenol A diglycidyldimethacrylate (Bis-DMA) and triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) are the two monomers most commonly utilised in orthodontic adhesive resins.6

Bisphenol-A (BPA) is the primary monomer of composite resins, and it is the precursor to bisphenol-A-glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) and bisphenol-A-dimethacrylate (Bis-DMA). Monomers like bisphenol-A are released during the leaching process which leads to skin allergies, cell death and high hemolytic activity.7,8 It is known that BPA is an endocrine disruptor that may affect reproductive, psychological, cognitive, and endocrine functions.9 BPA is not a direct component of dental adhesive materials, but its derivatives are widely used, especially bisphenol-Aglycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA).10 The genotoxic properties of orthodontic adhesives are essential for determining the biologicalsafety of materials. The toxic effects of BisGMA has been reported in MCF-7 human breast Cancer cells, L929 mouse fibroblast, or S9 rat hepatic cells.11 The mortality in Zebra fish was reported at 1 μM of Bis-GMA.12 The toxicity of BisGMA and other Bisphenol derivatives released from resin composites have been extensively reviewed by Lopes-Rocha et al.13 Results suggest that BisGMA could increase nitric oxide, ROS, and inflammatory cytokines in macrophages and activates macrophages via NF-κB activation, IκB degradation, and p-Akt activation.14 But no significant toxic effects of BisGMA was reported in the reproductive functionality in male and female on set doses of the dental resin monomer bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate.15 Due to ethical reasons the genotoxicity studies cannot be directly performed on humans. Therefore, National Toxicological Programme has suggested the development and validation of alternatives models for the toxicological evaluations. For traditional toxological studies, a shift has taken place from the use of mammalian models to alternative models such as Drosophila, Zebrafish, C.elegans.16 Evaluation of BisGMA- induced genotoxic stress, tissue damage and the quantification of hsp70 expression in terms of β-galactosidase activity is new to investigate using Drosophila as a model. The European Centre for the validation of Alternative Method (EVCAM) recommended the use of Drosophila as an alternative model for scientific studies.17 Hence, fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is selected for present study. While some studies focused on exposure to BPA from restorativeresin compositesonly a few studies are available on orthodontic resins.10 The aim of this study was to evaluate the cytotoxic and genotoxic effect of BisGMA present in methacrylate based orthodontic adhesives such as Transbond MIP, Transbond XT light cure adhesive primer and Scotchbond Universal Adhesive.18

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Bisphenol-A glycidyl methacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich; USA; CAS: 1565-94-2) Trypan (CAS: 72-57-1; Lobachemie, India); Methyl Methanesulphonate (MMS) extrapure, 99% CAS: 66-27-3; SRL, India); Collagenase Type I (CAS: 9001-12-1; Himedia, India); Acridine orange (CAS: 10127-02-3; Sigma-Aldrich); Ethidium Bromide (CAS: 1239-45-8; SRL, India); Ellman’s reagent (CAS: 69-78-3; SRL, India); Glutathione Oxidized (GSSG) extrapure, 99% (CAS: 27025-41-8; SRL, India); Glutathione Reduced (GSH) extrapure, 99% (CAS: 70-18-8; SRL, India); 1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CAS: 97-00-7; Sigma-Aldrich); o-Nitrophenyl-ß-D-Galacto Pyranoside (ONPG) extrapure, 99% (CAS: 369-07-3; SRL, India); 5-Bromo-4-Chloro-3-Indolyl-ß-D-Galactopyranoside (X-Gal) for molecular biology, 98% (CAS: 7240-90-6; SRL, India); Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) pure, 99% (CAS: 128-37-0; SRL, India); Thiobarbituric acid (CAS: 504-17-6; CDH, India); Orthophosphoric acid (CAS: 7664-38-2; Fisher Scientific, India).

Fly strain

A transgenic D. melanogaster with a transformation vector inserted with P-element and containing a wild-type hsp70 sequence up to the lacZ fusion point (which encodes β-galactosidase enzyme) was used in this study. The chosen transgenic D. melanogaster line expresses bacterial β-galactosidase as a response to stress alongwithhsp70.19 The flies and larvae were cultured on standard Drosophila food containing agar, maize powder, sugar, and yeast at 24 °C ± 1 °C.20 Whole larvae, internal tissues and mid gut cells of larvae were used for the study.

Experimental design

The LC50 was calculated by exposing the larvae to various doses i.e. exposed to 0.025 M, 0.050 M, 0.100 M, 0.150 M, and 0.200 M of BisGMA for 24 h and the 50% mortality was observed at 0.100 M of BisGMA. Hence, the highest tested dose was kept less than 1/4th of the LC50.21 The BisGMA at final concentration of 0.005 M, 0.010 M, 0.015 M and 0.020 M wasmixed inDrosophila standard diet and the third instar larvae were allowed to feed on it for 24 h. Methyl methanesulphonate at a dose of 80 μM was taken as a positive control in the present study.

Soluble O-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) assay (quantitative)

The larvae were washed in the phosphate buffer (PB) and were put in an Eppendorf (20 larvae per tube; 5 replicates per group), permeabilized for 10 min by acetone, and incubated in the incubatorovernight at 37 °C in 600 μL of ONPG buffer. After incubation, the reaction was stopped by adding 300 μL of Na2CO3. The extent of the reaction was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 420 nm. ONPG assay quantifies the expression of hsp70 in terms of β-galactosidase activity which gives a measure of cytotoxicity.22

In situ histochemical β-galactosidase activity (qualitative)

The larvae (10 larvae/treatment; 5 replicates/group) were dissected out in Pole’s Salt Solution (PSS) and X-gal staining was performed on internal tissues of larvae using the method as described by Chowdhuri et al.23 The larvae explants were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, washed in 50 μM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and stained overnight in X-gal staining solution at 37 °C in the dark and stained slides examined underthe microscope.

Trypan blue exclusion test

The extent of the tissue damage was evaluated by the dye exclusion test. Briefly, the internal tissues of larvae were explanted in a drop of phosphate buffer (PB), rotated in trypan blue stain for 30 min, washed thoroughly in PB, and scored immediately for dark blue staining under light microscope. The larvae (5 larvae per dose; 5 replicates per group) were scored for the trypan blue staining on an average composite index per larvae.24 No colour 0 (more viable cells), Any blue-1, Darkly stained nuclei-2, Large patches of darkly stained cells-3and complete staining of most cells in the tissue-4 (less viable cells or more dead cells).

Preparation of homogenate for biochemical assays

For performing the biochemical assays, third instar larvae (50 larvae per treatment; 5 replicates per group) were homogenized in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and centrifuged at 9,000 g and the obtained supernatant was used to perform biochemical assays.25

Estimation of glutathione (GSH) content

For the estimation of GSH content Ellman’s reagent (DTNB) was used according to the procedure described by Jollow et al.26 The assay mixture consisted of 550 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer, 100 μL of supernatant and 100 μL of DTNB. The optical density (OD) was read at 412 nm and the results were expressed as μmoles of GSH/gram tissue.

Estimation of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity

GST activity was determined by the method of Habig et al.27 The reaction mixture consisted of 500 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer, 150 μL of 10 mM 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (CDNB), 200 μL of 10 mM reduced GSH and 50 μL of supernatant. The OD was taken at 340 nm and the enzyme activity was expressed as μmoles of CDNB conjugates/min/mg protein.

Estimation of thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS)

TBARS was measured according to the method described by Ohkawa et al.28 The reaction mixture consisted of 5 μL of 10 mM butyl-hydroxy toluene (BHT), 200 μL of 0.67% thiobarbituric acid, 600 μL of 1% O-phosphoric acid, 105 μL of distilled water and 90 μL of supernatant. The resultant mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 45 min and the OD was measured at 535 nm. The results were expressed as nmoles of thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS) formed/hour/gram tissue.

Apoptosis study

Apoptotic index

The apoptotic index for the cells of the mid-gut of the larvae was estimated according to the method proposed by Shakya et al.29 The midguts of the larvae were explanted in Pole Salt’s Solution (PSS). The PSS was replaced by 300 mL of collagenase (0.5 mg/mL) and kept for 15 min at 25 °C. The collagenase was removed and the pellet was washed three times by phosphate buffer solution (PBS)with gentle shaking.29,30 Finally, the pellet was suspended in 80 mL of PBS. About 25 mL of cell suspension was mixed with 2 mL of Ethidium bromide/acridine orange dye. 100 cells were scored per treatment under fluorescent microscope (five replicates/group) for estimating the apoptotic index.

Caspase-3 (Drice) and Caspase-9 (Dronc) activities

The assay was performed according to the manufacturer protocol (Bio-Vision, CA, USA). The assay was based on spectrophotometric detection of the chromophore p-nitroanilide (pNA) obtained after specific action of caspase-3 and caspase-9 on tetrapeptide substrates, DEVD-pNA and LEHD-pNA, respectively. The assay mixture (50 μL of cell suspension and 50 μL of chilled cell lysis buffer) was incubated on ice for 10 min. After incubation, 50 μL of 2 X reaction buffer (containing 10 mM DTT) with 200 μM substrate (DEVD-pNA for Drice, and IETD-pNA for Dronc) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h. The reaction was quantified at 405 nm.

Comet assay

The comet assay in the present study was performed according to the method of Mukhopadhyay et al.30 The midguts from 20 larvae were explanted in Pole Salt’s Solution (PSS) in a microcentrifuge tube. PSS in micro centrifuge tube was then replaced by 300 μL of collagenase (0.5 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4) and kept for 15 min at 25 °C. The cell suspension was prepared by washing three times in PBS and finally the cells were suspended in 80 μL of PBS. Then the slides were subjected to electrophoresis (300 Mm NaOH/1 Mm EDTA) (Ph > 13), followed by neutralization (0.4 M Tris-HCL) and stained with ethidium bromide (20 μg/mL; 75 μL/slides) for 10 min in dark. The slides were then dipped in chilled distilled water to remove the excess of stain and subsequently cover slips were placed over them. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the slides were prepared in duplicate. Twenty-five cells per slide were randomly captured under fluorescent microscope at a constant depth of the gel, and mean tail length was calculated to measure DNA damage by using comet score 1.5 software (TriTek Corporation, Sumerduck, Virginia).

Statistical analysis

The data was subjected to statistical analysis through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by posthocTukey test using GraphPad Prism software [version 5.0]. The level of significance was kept at P < 0.05. The results were expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

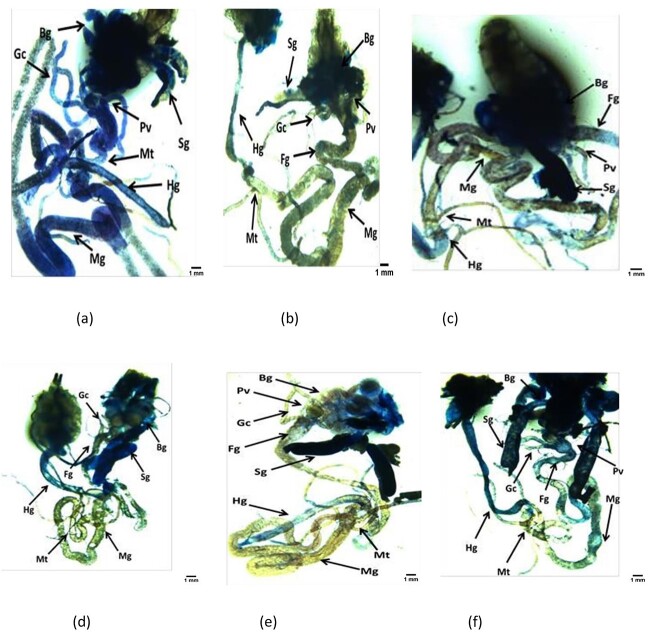

The results obtained for β-galactosidase activity is shown in fig. 1. The larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not showed significant increase in the activity of β-galactosidase, but the larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a significant increase of 3.20, 6.52 and 9.75 folds, respectively, in the β-galactosidase activity compared to control (Fig. 1; P < 0.05). The results obtained for the X-gal activity is shown in fig. 2(a–f). A dose dependent activity of β-galactosidase was observed on the exposure of third instar larvae to 0.005, 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA (Fig. 2a–f).

Fig. 1.

Quantification of β- galactosidase activity in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 after the exposure to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h. [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control;*significant at P < 0.05 compared to control].

Fig. 2.

X-gal staining performed on the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 after the exposure to various doses of Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate(Bis-GMA) for 24 h [positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM (a); control (b); BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M (c); BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M (d); BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M (e); BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M (f); BG-brain ganglia, SG-salivary gland, PV-Proventriculus, FG-foregut, MG-Midgut, HG-hindgut, MT-Malpighian tubule, GC-gastric caeca].

The results obtained for the trypan blue staining are shown in fig. 3(a–f) and the same has been quantified in Fig. 4. The larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not showed significant tissue damage compared to control (Fig. 4; P < 0.05), but the larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a dose dependent significant increase of 2.03, 2.57 and 3.46 folds, respectively, in the tissue damage compared to control (Fig. 4; P < 0.05). A dose dependent tissue damage was observed in brain, salivary glands, proventriculus, gastric caeca, foregut, midgut and malphighian tubules.

Fig. 3.

Trypan staining performed on the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 after the exposure to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM) (a); control (b); BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M (c); BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M (d); BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M (e); BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M (f); BG-brain ganglia, SG-salivary gland, PV-Proventriculus, FG-foregut, MG-Midgut, HG-hindgut, MT-Malpighian tubule, GC-gastric caeca].

Fig. 4.

Quantification of tissue damage after performing trypan staining on the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control].

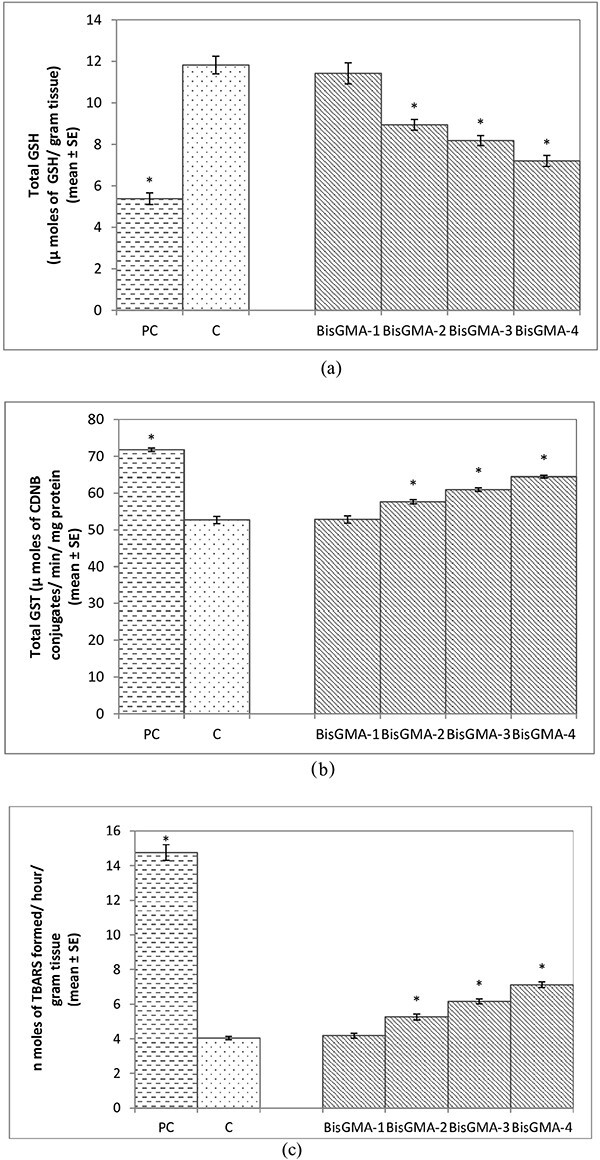

The larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not show a significant decrease in the GSH content compared to control (Fig. 5a; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a significant decrease of 1.32, 1.44 and 1.64 folds, respectively, in the GSH content compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 5a; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.005 of BisGMA did not show a significant increase in the activity of GST (Fig. 5b; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a significant increase of 1.09, 1.15 and 1.22 folds, respectively, in the activity of GST compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 5b; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not show a significant increase in the TBARS (Fig. 5c; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a dose dependent significant increase in TBARS of 1.30, 1.52 and 1.76 folds, respectively, compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 5c; P < 0.005).

Fig. 5.

a) Quantification of glutathione content in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate(Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control]. b) Quantification of glutathione-S-transferase activity in the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate(Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control]. c) Quantification of lipid peroxidation in the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate =80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control].

The results obtained for apoptotic index are shown in fig. 6a. The exposure of third instar larvae to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not showed significant increase in the apoptotic index compared to control (Fig. 6a; P < 0.05), but the larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a dose dependent increase of 1.65, 2.2 and 2.95 folds, respectively, in the apoptotic index compared to control (Fig. 6a; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMAdid not show a significant increase in the activity of Caspase-3 compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 6b; P < 0.005). The larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a significant increase of 1.46, 1.87 and 2.73 folds, respectively, in the activity of Caspase-3 compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 6b; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not show a significant increase in the activity of Caspase-9 compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 6c; P < 0.05). The larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a significant increase OF 1.47, 2.11 and 2.82 folds in the activity of Caspase-9 compared to unexposed larvae (Fig. 6c; P < 0.05). The results obtained for comet assay are shown in fig. 7(a–f). The quantification of the DNA damage is shown in Fig. 7b. The midgut of the larvae exposed to 0.005 M of BisGMA did not showed significant increase in the DNA damage compared to control (Fig. 7b; P < 0.05), but the larvae exposed to 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 M of BisGMA showed a dose dependent significant increase of 1.17, 3.0 and 4.04 folds, respectively, in the DNA damage compared to control (Fig. 7b; P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

a) Quantification of apoptosis after performing acridine orange (AO)/Ethidium bromide (Et-Br) stanning on the midgut cells of third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control]. b) Quantification of Caspase-3 activityin the mid gut cells of the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control]. c) Quantification of Caspase-9 activityin the mid gut cells of the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control].

Fig. 7.

a) Comet assay performed on the mid gut cells of the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) for 24 h [control (a); BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M (b); BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M (c); BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M (d); BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M (e); positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM) (f)]. b) Quantification of DNA damage after performing comet assay on the mid gut cells of the third instar larvae of transgenic D. melanogaster (hsp70-lac Z)Bg9 exposed to various doses of Bisphenol A- glycidyl methacrylate(Bis-GMA) for 24 h [BisGMA-1 = 0.005 M; BisGMA-2 = 0.010 M; BisGMA-3 = 0.015 M; BisGMA-4 = 0.020 M; positive control (methyl methane sulphonate = 80 μM); C = control; *significant at P < 0.05 compared to control].

Discussion

The recent rise in popularity of direct-bonding procedures has a significant impact on the need for biocompatibility testing in orthodontics. Several studies have evaluated numerous orthodontic adhesives, but compared to the whole material, individual component of the material possess different cytotoxic effects.31–33 Thompson et al34 concluded that upto 14% of unpolymerized resin (mainly BisGMA) had leached out from completely cured adhesives and causes potential cytotoxicity. Whereas, according to Ferracane and Greener35 only 5%–10% of unreacted monomer may have eluted from solidified adhesives. Numerous studies evaluated the adverse effects of monomer that causes cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, mutagenicity and toxic reactions to the reproductive system.36–39 There is also evidence of perioral dermatitis, lip swelling and stomatitis reported in the research studies.40–42 Released monomer from methacrylate-based adhesives can enter the body through three different routes: absorption through the gastrointestinal tract, diffusion through the dentinal tubules to the pulp, and inhalation of volatile components in the lungs. On the basis of monomers, the cytotoxic effect has been graded as follows: BisGMA> UDMA > TEGDMA >HEMA.43 Therefore, the present study was undertaken for the assessment of genotoxicity and cytotoxicity of BisGMA present in resin-based adhesives by using D.melanogaster as an in vivo model. Exploitation of hsp70 expression plays a defensive role in living organisms during minor assaults to the tissues. When the toxicant injury extends beyond a particular threshold, hsp70 expression stops protecting the cell.22 Likewise, in the present study, cytotoxicity of BisGMA was evaluated in terms of tissue damage and other biological effects on hsp70 expression. At lower concentrations of BisGMA (0.005 M), hsp70 expression could buffer the cells against further cellular damage as evidenced by an absence of trypan blue staining in the exposed larvae. However, at the highest concentration of the BisGMA (0.010 M, 0.015 M and 0.020 M), a moderate to severe trypan blue staining indicates that hsp70 expression was insufficient to alleviate tissue damage. The high damage was found to be in salivary glands, brain ganglia, proventriculus, mid gut, and hind gut of the exposed larvae. Since the surrounding haemolymph fuels the brain ganglia and salivary glands, they are liable to be damaged when the toxicant enters the haemolymph.44

Kleinsasser et al.45 reported his first in vitro study on human cell lines of human salivary gland and lymphocytes for bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA) and triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) and concluded dose dependent damage of DNA for both materials.

In vitro studies have demonstrated that persistent TEGDMA can result in DNA chain sequence loss, which results in chromosomal abnormalities.46,47 Additionally, it has been shown that solutions containing Bis-GMA at a concentration of 5 μmol/liter slow down the process of synthesizing DNA. In vivo studies mentioned in the literature by Davidson et al48 on hamsters experimental model evaluated the toxicity of resin based adhesives. They reported the gross irritation and histologic inflammation in tested animals by constant leaching of unreacted monomer i.e. BisGMA from cured adhesives. Drozdz et al49 performed study on lymphocytes to evaluate the cytotoxicity of BisGMA. In CCRF-CEM cells, the monomer at 1 mM induced a delay in the S-phase of cell cycle and has the capacity to cause a significant double-strand DNA break. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of BisGMA, were studied on human fetal lung fibroblasts MRC-5 using MTT and Comet assay. BisGMA was found to exhibit cytotoxic as well as genotoxic.50

Lipid peroxidation is the oxidative deterioration of polyunsaturated lipids due to free radical generation.51 The high doses of BisGMA can induce oxidative stress and is evident by the increase in the formation of TBARS, reduced levels of GSH and increase in the activity of GST in our study. The agents responsible for altering the Glutathione concentration affect the transcription of detoxification enzymes.52 BisGMA has been reported to cause a significant depletion in the levels of GSH content in the cultured primary human gingival fibroblasts.53 GST is also a one of the important detoxifying enzymes the expression of which is probably regulated by the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).54 The results in our study suggest the increase in the activity of GST at higher doses of BisGMA. The Caspase-3 and 9 are the major markers of the initiation of apoptosis. In our present study the activity of Caspase-9 and 3 was based on spectrophotometric detection of the chromophore p-nitroanalide (PNA) obtained after the specific action of Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 on tetrapeptide substrates, acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-p-nitroanilide (DEVD-PNA) and Ac-leu-Glu-His-Asp-p-nitroanilide (LEHD-PNA), respectively. During the initiation of apoptosis Caspase-9 & 3 are the first to increase during the initiation of apoptosis.55 BisGMA has been reported to induce the formation of Reactive oxygen species (ROS).56 BisGMA induced a depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential and increase in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, and activation of Caspase-3 in exposed human oral Keratinocytes.57 In our present study the exposure at the high doses of BisGMA showed a significant increase in the activity of Caspase-3 & 9, which suggest that at high dose it can also triggers apoptosis. The results were further corroborated with the results obtained for apoptotic index. The assay performed for apoptotic cell analysis showed a greater number of apoptotic cells at higher doses of BisGMA i.e. 0.010 M, 0.015 M and 0.020 M while non- significant results were obtained at 0.005 M concentration of BisGMA that can be considered as no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL). The cells of the midgut of the larvae have the maximum amount of cytochrome oxidases. The gut cells are the main targets for substances because the majority of chemicals enter the body through gut via food.58 That’s why, in current study comet assay was performed on the mid-gut tissues of 3rd instar larvae of D. melanogaster to assess the genotoxicity of BisGMA. The results of this assay were suggestive of the genotoxic damage at 0.010 M, 0.015 M and 0.020 M of BisGMA after 24 h of exposure. Most of the studies are in vitro but the present study on 3rd instar larvae of D.melanogaster have been performed for the first time. In contrast, the present study reported the safe concentration of BisGMA. The study conducted by Li et al59 on murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 demonstrated that the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity induced by BisGMA are mediated by DNA damage and Caspase activation. Earlier Drosophila has been used to evaluate the genotoxic effects of aqueous extracts from dental composite resins using Drosophila Wing spot test.60 Also, the homologous mitotic recombination, as well as the effects on point and chromosomal mutations, were assessed in the somatic proliferative cells of D. melanogaster exposed to aqueous extracts of dental composite resins (Charisma, Fill Magic, Fill Magic Flow, Durafill, TPH Spectrum, Concept, Natural Look, Filtek Z250 and Filtek P60).60 Findings revealed that Adhesive like Adper Single Bond Plus and Prime & Bond 2.1 are inducers of toxic-genetic events, primarily through the mechanism of mitotic recombination.61 Further, Drosophila larvae exposed to various doses of sodium hypochlorite which is commonly used in mouthwashes showed significant increase oxidative stress markers, tissue damage, and DNA damage.62 Results support that monomers of dental resins triethyleneglycoldimethacrylate (TEGDMA), urethanedimethacrylate (UDMA) had significant influence on overall spot frequencies in the SMART assay in D. melanogaster, implying the presence of genotoxic effects.63 BisGMA has been reported to increase lipid peroxidation and DNA oxidation.64Drosophila possesses a compact genome, with many genes having identifiable orthologs in humans. Its short lifespan and prolific reproductive capacity facilitate swift experimentation and the observation of multiple generations, enabling the examination of long-term effects, generational impacts, or chronic exposures in a relatively condensed timeframe compared to lengthier-lived organisms. Notably, Drosophila tends to exhibit observable phenotypic changes in response to environmental exposures or genetic modifications, offering noticeable indicators of potential health impacts. These phenotypic alterations provide a foundation for subsequent investigations in more intricate organisms.

Conclusion

Following conclusions are drawn from present study –

-

BisGMA above the concentration of 0.005 M on third instar larvae of D. melanogaster showed significant -

Expression of hsp70 (response to cellular stress) as tested by soluble-O-nitrophenyl -β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) assay and X-gal staining.

Dose dependant tissue damage as evaluated by trypan blue staining.

Dose dependent increase in the oxidative stress.

Dose dependent increase in the apoptotic markers.

Dose dependent increase in the DNA damage.

Safe dose of BisGMA on third instar larvae of D. melanogaster was found to be 0.005 M.Limitation of this study includes the short duration of 24 h studied due to which we are unable to evaluate the long-term adverse effect of resin-based adhesives as orthodontic fixed appliances remains in mouth for longer duration of treatment. Also, as the present study was done on 3rd instar larvae of D. melanogaster, so to ensure the biocompatibility, further studies should be done on human cell lines.

Author contributions

Concept: NI, MT, AA YHS; Design: MT, NI, AA, YHS; Data collection: NI, MT, AA, HV, KJ, IS; Analysis: NI, MT, AA, SJ, YHS; Literature review: NI, MT, AA, YHS; Writing: NI, MT, YHS.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Chairperson, Department of Zoology, AMU for providing laboratory facilities.

Contributor Information

Nabeela Ibrahim, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Dental College Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

Mohammad Tariq, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Dental College Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

Arbab Anjum, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Dental College Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

Himanshi Varshney, Laboratory of Alternative Animal Models, Section of Genetics, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

Kajal Gaur, Laboratory of Alternative Animal Models, Section of Genetics, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

Iqra Subhan, Laboratory of Alternative Animal Models, Section of Genetics, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

Smita Jyoti, Department of Zoology, School of Sciences, IFTM University, Moradabad, UP, 244102, India.

Yasir Hasan Siddique, Laboratory of Alternative Animal Models, Section of Genetics, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, UP, 202002, India.

References

- 1. Alkadhimi A, Motamedi F. Orthodontic adhesives for fixed appliances: a review of available systems. Dent Update. 2019:46(8):742–758. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gange P. The evolution of bonding in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015:147(4):S56–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Papakonstantinou AE, Eliades T, Cellesi F, Watts DC, Silikas N. Evaluation of UDMA's potential as a substitute for Bis-GMA in orthodontic adhesives. Dent Mater. 2013:29(8):898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahrari F, Tavakkol Afshari J, Poosti M, Brook A. Cytotoxicity of orthodontic bonding adhesive resins on human oral fibroblasts. Eur J Orthod. 2010:32(6):688–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Angiero F, Farronato G, Dessy E, Magistro S, Seramondi R, Farronato D, Benedicenti S, Tetè S. Evaluation of the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of orthodontic bonding adhesives upon human gingival papillae through immunohistochemical expression of p53, p63 and p16. Anticancer Res. 2009:29(10):3983–3987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bationo R, Ouédraogo Y, Kaboré AD, Doulgou D, Beugré-Kouassi MLA, Jordana F, Beugré B. Release of bisphenol a and TEGDMA from orthodontic composite resins. IOSR-JDMS. 2019:18:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reichl FX, Esters M, Simon S, Seiss M, Kehe K, Kleinsasser N, Folwaczny M, Glas J, Hickel R. Cell death effects of resin-based dental material compounds and mercurials in human gingival fibroblasts. Arch Toxicol. 2006:80(6):370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fujisawa S, Imai Y, Fujisawa, Kojima K, Fujisawa, Masuhara E. Studies on hemolytic activity of bisphenol A diglycidyl methacrylate (BIS-GMA). J Dent Res. 1978:57(1):98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marzouk T, Sathyanarayana S, Kim AS, Seminario AL, McKinney CM. A systematic review of exposure to bisphenol a from dental treatment. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019:4(2):106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deviot M, Lachaise I, Högg C, Durner J, Reichl FX, Attal JP, Dursun E. Bisphenol A release from an orthodontic resin composite: a GC/MS and LC/MS study. Dent Mater. 2018:34(2):341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kostoryz EL, Eick JD, Glaros AG, Judy BM, Welshons WV, Burmaster S, Yourtee DM. Biocompatibility of hydroxylated metabolites of BISGMA and BFDGE. J Dent Res. 2003:82(5):367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kramer AG, Vuthiganon J, Lassiter CS. Bis-GMA affects craniofacial development in zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio). Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016:43:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopes-Rocha L, Ribeiro-Gonçalves L, Henriques B, Özcan M, Tiritan ME, Souza JCM. An integrative review on the toxicity of Bisphenol A (BPA) released from resin composites used in dentistry. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2021:109(11):1942–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuan YH, Huang FM, Li YC, Chang YC. Proinflammatory activation of macrophages by bisphenol A-glycidyl-methacrylate involved NFκB activation via PI3K/Akt pathway. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012:50(11):4003–4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moilanen LH, Dahms JK, Hoberman AM. Reproductive toxicity evaluation of the dental resin monomer bisphenol a glycidyl methacrylate (CAS 1565-94-2) in mice. Int J Toxicol. 2013:32(6):415–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rand MD. Drosophotoxicology: the growing potential for Drosophila in neurotoxicology. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010:32(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rocha JBT. Drosophila melanogaster as a promising model organism in toxicological studies. Arc Basic Appl Med. 2013:1(1):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taubmann A, Willershausen I, Walter C, al-Maawi S, Kaina B, Gölz L. Genotoxic and cytotoxic potential of methacrylate-based orthodontic adhesives. Clin Oral Investig. 2021:25(5):2569–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Siddique YH, Fatima A, Jyoti S, Naz F, Rahul, Khan W, Singh BR, Naqvi AH. Evaluation of the toxic potential of graphene copper nanocomposite (GCNC) in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. PLoS One. 2013:8(12):80944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siddique YH, Ara G, Faisal M. Effect of ethinylestradiol on hsp70 expression in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster(hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. Pharmacologyonline. 2011:1(1):398–405. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fatima A, Khanam S, Rahul R, Jyoti S, Naz F, Ali F, Siddique YH. Protective effect of tangeritin in transgenic Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2017:9(1):44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nazir A, Mukhopadhyay I, Saxena DK, Siddiqui MS, Chowdhuri DK. Evaluation of toxic potential of captan: induction of hsp70 and tissue damage in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2003:17(2):98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chowdhuri DK, Saxena DK, Viswanathan PN. Effect of Hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), its isomers, and metabolites on Hsp70 expression in TransgenicDrosophila melanogaster. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1999:63(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rahul JS, Jyoti S, Shakya B, Naz F. Effect of Ecalyptuscitriodora extract on hsp70 expression and tissue damage in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. Phytopharmacology. 2012:3(2):111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shakya B, Siddique YH. Evaluation of the toxic potential of arecoline toward the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. Toxicol Res. 2018:7(3):432–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Zampaglione N, Gillette JR. Bromobenzene-induced liver necrosis. Protective role of glutathione and evidence for 3,4-bromobenzene oxide as the hepatotoxic metabolite. Pharmacology. 1974:11(3):151–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione-S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturicacid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974:249(22):7130–7139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979:95(2):351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shakya B, Shakya S, Hasan Siddique Y. Effect of geraniol against arecoline induced toxicity in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2019:29(3):187–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mukhopadhyay I, Chowdhuri DK, Bajpayee M, Dhawan A. Evaluation of in vivo genotoxicity of cypermethrin in Drosophila melanogaster using the alkaline comet assay. Mutagenesis. 2004:19(2):85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pudpong N, Anuwongnukroh N, Dechkunakorn S, Wichai W, Tua-Ngam P. Cytotoxicity of three light-cured orthodontic adhesives. Key Engi Mat. 2018:777:582–586. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jonke E, Franz A, Freudenthaler J, Konig F, Bantleon HP, Schedle A. Cytotoxicity and shear bond strength of four orthodontic adhesive systems. Eur J Orthod. 2008:30(5):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Söderholm KJ, Mariotti A. BIS-GMA-based resins in dentistry: are they safe? J Am Dent Assoc. 1999:130(2):201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson VP, Williams EF, Bailey WJ. Dental resins with reduced shrinkage during hardening. J Dent Res. 1979:58(5):1522–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ferracane JL, Greener EH. Fourier transform infrared analysis of degree of polymerization in unfilled resins—methods comparison. J Dent Res. 1984:63(8):1093–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Issa Y, Watts DC, Brunton PA, Waters CM, Duxbury AJ. Resin composite monomers alter MTT and LDH activity of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Dent Mater. 2004:20(1):12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Michelsen VB, Kopperud HBM, Lygre GB, Björkman L, Jensen E, Kleven IS, Svahn J, Lygre H. Detection and quantification of monomers in unstimulated whole saliva after treatment with resin-based composite fillings in vivo. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012:120(1):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miletic V, Santini A, Trkulja I. Quantification of monomer elution and carbon–carbon double bonds in dental adhesive systems using HPLC and micro-Raman spectroscopy. J Dent. 2009:37(3):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Durner J, Dębiak M, Bürkle A, Hickel R, Reichl FX. Induction of DNA strand breaks by dental composite components compared to X-ray exposure in human gingival fibroblasts. Arch Toxicol. 2011:85(2):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moharamzadeh K, van Noort R, Brook IM, Scutt AM. Cytotoxicity of resin monomers on human gingival fibroblasts and HaCaT keratinocytes. Dent Mater. 2007:23(1):40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schweikl H, Hiller KA, Bolay C, Kreissl M, Kreismann W, Nusser A, Steinhauser S, Wieczorek J, Vasold R, Schmalz G. Cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of dental composite materials. Biomaterials. 2005:26(14):1713–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goldberg M. In vitro and in vivo studies on the toxicity of dental resin components: a review. Clin Oral Investig. 2008:12(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Darmani H, Al-Hiyasat AS, Milhem MM. Cytotoxicity of dental composites and their leached components. Quintessence Int. 2007:38(9):789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sarkar S, Roy A, Roy S. Flubendiamide affects visual and locomotory activities of Drosophila melanogaster for three successive generations (P, F 1 and F 2). Invertebr Neurosci. 2018:18(2):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kleinsasser NH, Schmid K, Sassen AW, Harréus UA, Staudenmaier R, Folwaczny M, Glas J, Reichl FX. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of resin monomers in human salivary gland tissue and lymphocytes as assessed by the single cell microgel electrophoresis (comet) assay. Biomaterials. 2006:27(9):1762–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jagdish N, Padmanabhan S, Chitharanjan AB, Revathi J, Palani G, Sambasivam M, Sheriff K, Saravanamurali K. Cytotoxicity and degree of conversion of orthodontic adhesives. Angle Orthod. 2009:79(6):1133–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Malkoc S, Corekci B, Ulker HE, Yalçın M, Şengün A. Cytotoxic effects of orthodontic composites. Angle Orthod. 2010:80(4):759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davidson WM, Sheinis EM, Shepherd SR. Tissue reaction to orthodontic adhesives. Am J Orthod. 1982:82(6):502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Drozdz K, Wysokinski D, Krupa R, Wozniak K. Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate induces a broad spectrum of DNA damage in human lymphocytes. Arch Toxicol. 2011:85(11):1453–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Manojlovic D, Dramićanin MD, Miletic V, Mitić-Ćulafić D, Jovanović B, Nikolić B. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of a low-shrinkage monomer and monoacylphosphine oxide photoinitiator: comparative analyses of individual toxicity and combination effects in mixtures. Dent Mater. 2017:33(4):454–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Puntel RL, Roos DH, Paixão MW, Braga AL, Zeni G, Nogueira CW, Rocha JBT. Oxalate modulates thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS) production in supernatants of homogenates from rat brain, liver and kidney: effect of diphenyl diselenide and diphenyl ditelluride. Chem Biol Interact. 2007:165(2):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jones DP. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Methods Enzymol. 2002:348:93–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Engelmann J, Janke V, Volk J, Leyhausen G, von Neuhoff N, Schlegelberger B, Geurtsen W. Effects of BisGMA on glutathione metabolism and apoptosis in human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2004:25(19):4573–4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hayes JD, Pulford DJ. The glut athione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the lsoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance part I. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995:30(6):445–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kumar S, Doumanis J. The fly caspases. Cell Death Differ. 2000:7(11):1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chang MC, Chen LI, Chan CP, Lee JJ, Wang TM, Yang TT, Lin PS, Lin HJ, Chang HH, Jeng JH. The role of reactive oxygen species and hemeoxygenase-1 expression in the cytotoxicity, cell cycle alteration and apoptosis of dental pulp cells induced by BisGMA. Biomaterials. 2010:31(32):8164–8171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhu Y, Gu YX, Mo JJ, Shi JY, Qiao SC, Lai HC. N-acetyl cysteine protects human oral keratinocytes from Bis-GMA-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by inhibiting reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and the PI3K/Akt pathway. Toxicol in Vitro. 2015:29(8):2089–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. de Navascués J, Perdigoto CN, Bian Y, Schneider MH, Bardin AJ, Martínez-Arias A, Simons BD. Drosophila midgut homeostasis involves neutral competition between symmetrically dividing intestinal stem cells. EMBO J. 2012:31(11):2473–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Li YC, Kuan YH, Huang FM, Chang YC. The role of DNA damage and caspase activation in cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of macrophages induced by bisphenol-A-glycidyldimethacrylate. Int Endod J. 2012:45(6):499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Arossi GA, Dihl RR, Lehmann M, Reguly ML, de Andrade HHR. Genetic toxicology of dental composite resin extracts in somatic cells in vivo. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010:107(1):625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Arossi GA, Dihl RR, Lehmann M, Cunha KS, Reguly ML, de Andrade HH. In vivo genotoxicity of dental bonding agents. Mutagenesis. 2009:24(2):169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mukhtar-Un-Nisar Andrabi S, Tamanna S, Rahul, Naz F, Siddique YH. Toxic potential of sodium hypochlorite in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. Toxin Rev. 2022:41(3):891–903. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Arossi GA, Lehmann M, Dihl RR, Reguly ML, de Andrade HHR. Induced DNA damage by dental resin monomers in somatic cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010:106(2):124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yıldız M, Alp HH, Gül P, Bakan N, Özcan M. Lipid peroxidation and DNA oxidation caused by dental filling materials. J Dent Sci. 2017:12(3):233–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]