Abstract

Objective

Electronic mental health interventions are effective but not well promoted currently among older adults. This study sought to systematically review and summarize the barriers and facilitators of accepting and implementing electronic mental health interventions among older adults.

Methods

We comprehensively retrieved six electronic databases from January 2012 to September 2022: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. The JBI-QARI was used to assess the quality of the research methodology of each publication. Eligible studies underwent data coding and synthesis aligned to inductive and deductive methods. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research 2.0 was used as a deductive framework to guide a more structured analysis.

Results

The systematic review screened 4309 articles, 17 of which were included (eight with mixed methods and nine with qualitative methods). We identified and extracted the barriers and facilitators of accepting and implementing electronic mental health interventions among older adults: (1) innovation: technology challenges, optimized functions, and contents, security and privacy; (2) outer setting: community engagement and partnerships, financing; (3) inner setting: leadership engagement, available resources, incompatibility, intergenerational support, training and guidance; (4) individuals: perceptions, capability, motivation of older adults and healthcare providers; and (5) implementation process: recruit, external assistance, and team.

Conclusion

These findings are critical to optimizing, promoting, and expanding electronic mental health interventions among older adults. The systematic review also provides a reference for better evidence-based implementation strategies in the future.

Keywords: eMental health, barriers, facilitators, older adults, qualitative systematic review

Introduction

As society rapidly ages, mental health issues among older adults have become a concern. The proportion of older adults worldwide is predicted to increase from 12% to 22% between 2015 and 2050. 1 Approximately 15% of adults aged 60 and older worldwide suffer from mental disorders, 2 which can affect their physical health and increase the risk of developing chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3–5 Severe mental disorders among old adults can even lead to premature death by harming themselves, which accounts for up to 25% of deaths among older people with psychological problems. 2 Therefore, addressing mental disorders among older adults is crucial for promoting their psychological and physical wellbeing. 6

Electronic mental health interventions (EMHIs) are a promising approach to meeting the mental health needs of older adults. 7 EMHIs utilize information and communication technology to provide mental health management, telepsychiatry counseling or treatment, and virtual communities of support groups.8,9 Mental health management means providing self-help or asynchronous psychological treatments or interventions using different devices (personal computer, laptop, or tablet) or smartphones (iPhone Operating System, Android, or Windows) to access online programs or applications. 10 Telepsychiatry counseling or treatment is defined as remote, synchronized, real-time, interactive assessments, consultations, and treatments provided by professional psychotherapists or trained volunteers via videoconferencing. 11 Virtual communities of support groups refer to online platforms where individuals with shared experiences, challenges, or interests come together to provide mutual support, share information, and foster a sense of community. 12

EMHIs have increased treatment availability at a lower cost while maintaining clinical outcomes comparable to face-to-face therapies and outperforming the waiting lists. 13 A systematic review (15 randomized controlled trials involving 3100 participants) demonstrated that the internet or telephone cognitive behavioral therapy reduced late-life depressive symptoms. 14 Also, technology-supported interventions potentially alleviated loneliness and helped socialize the home-isolated older adults. 15

Despite all the benefits of EMHIs, there are many barriers to adoption and promotion in older adults. The successful implementation of this technology depends on acceptance. A cross-sectional survey in the United States found that about 83% of older adults might not consider using technology to manage mental health. 16 More than two-thirds of healthcare providers did not have sufficient knowledge or resources to provide and implement EMHIs. 17 Meanwhile, only 7.7% of healthcare agencies reported using telehealth interventions for depression care, and they lack technological solutions to improve the workflow and quality of care. 18 Therefore, identifying barriers and facilitators from stakeholders is important in tackling this challenge.

By systematically searching the PubMed database, we failed to find existing reviews drawing this evidence together regarding the facilitators and barriers of EMHIs in older adults. Previous studies have explored these factors for EMHIs in adults and youth,19–23 but older adults may face unique challenges, such as difficulties understanding application interfaces, dexterity issues, a preference for human interaction, and cognitive concerns. 24 Some reviews summarized barriers and facilitators of digital intervention in the older population.25,26 However, they focused on chronic conditions but neglected the field of mental health. Thus, systematically summarizing the determinants of implementing EMHIs in older adults is necessary.

Qualitative research is a practical design to thoroughly understand stakeholders’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators. Synthesizing published qualitative studies helps integrate research evidence to apprehend a chosen topic better. The Comprehensive Framework for Implementation Research 2.0 (CFIR 2.0) is renowned for its comprehensive coverage across multiple domains, including innovation, inner and outer settings, individuals, and the implementation process. 27 This breadth allows for a thorough examination of factors influencing EMHI acceptance and implementation. Previous studies have successfully utilized CFIR 2.0 to identify barriers and facilitators.28–30 Meanwhile, the technology acceptance model (TAM), the reach effectiveness adoption implementation and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework, and normalization process theory (NPT) can be used to summarize effecting factors. However, TAM and NPT may not comprehensively capture the broader organizational and contextual factors. 31 RE-AIM's primary strengths lie in the evaluation and are more aptly suited for quantitative reviews. 32 Consequently, this study selects CFIR as the deductive framework for qualitative analysis.

Therefore, this review aims to summarize the barriers and facilitators to the acceptance and implementation of EMHIs among older adults, in order to inform better evidence-based implementation strategies for the future.

Method

Study design

The review was undertaken according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 checklist and was prospectively registered with PROSPERO, under the registration number: CRD42022361173.

Search strategy

The systematic literature search was conducted from January 2012 to September 2022 using six electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Additionally, a hand review of the reference lists from related studies was retrieved. The inclusion criteria specified that articles were limited to those published in English between January 2012 and September 2022, as articles from 10 years ago were potentially outdated due to the rapid evolution of electronic health interventions. Prior systematic assessment of digital health technology for mental illness has utilized 10 10-year range.23,33 The search strategy identified key terms related to four concepts: ‘older adults, eMental Health, mental disorder, and qualitative.’ Through browsing the literature, mental disorders in older adults identified included ‘loneliness, depression, anxiety, stress, distress.’ Relevant Mesh, non-Mesh, and thesaurus terms were used, and Boolean operators were used to link the keywords. The search syntax was adapted to suit each database. The benchmark definitions and search strings can be found in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

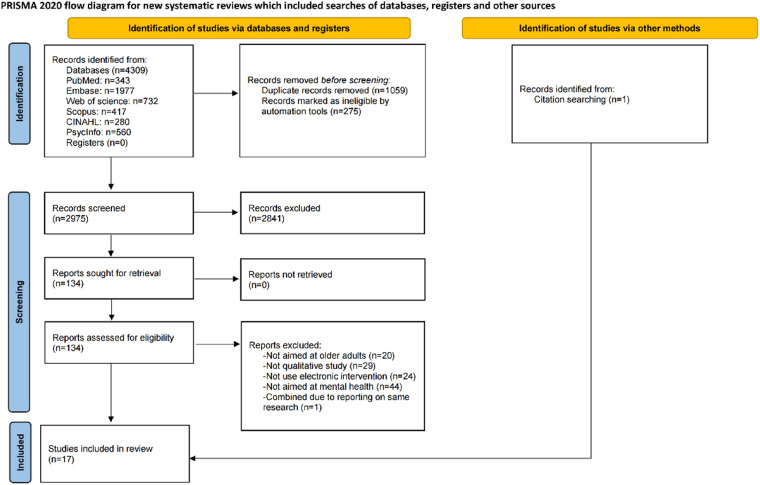

Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search identified 4309 publications imported into Endnote X20 software (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Endnote X20 and hand searching identified 1059 duplicates and 275 records marked as ineligible by automation tools, leaving 2975 papers assessed by title and abstract relevance. After the screening, 134 articles were found to fit the selection criteria, and the complete texts of these publications were retrieved for additional evaluation. After reading the entire content, 17 articles qualified for quality evaluation. The PRISMA diagram 2020 displays search results (Figure 1). Two authors (RP and XL) independently undertook the screening process. Any disagreements about inclusion were resolved through recourse to a third author (YG).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Study aspect | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Populations | (1) Participants: older adults (average age ≥ 60 years), (2) Providers: healthcare providers and healthcare agencies who provide EMHIs to older adults. | (1) Participants: children, adolescents, middle-aged adults, or if unable to obtain an age range; (2) Providers: healthcare providers and agencies that do not provide EMHIs to older adults. |

| Interventions | Meet both: (1) The study had an information and communication technology component (videoconference, web, or mobile technologies to deliver mental healthcare) (2) The psychotherapeutic intervention targeted a mental disorder. |

(1) Not using electronic intervention. (2) Not aimed at mental disorders. (3) Not implementing electronic health intervention. |

| Phenomena of interest | Barriers and facilitators | |

| Design | Qualitative methodology or mixed methods | Quantitative studies and mixed-method studies with predominantly quantitative results |

| Article type | Peer-reviewed journal articles and dissertation | Reviews, commentaries, editorials, protocol, and conference abstracts. |

| Language | English | All other languages |

EMHIs: electronic mental health interventions.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search process Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020).

Quality assessment

We utilized the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) to assess the quality of the research methodology of each publication. Each question answered as “yes” was assigned a score of 1. We added an entry Q11 to JBI-QARI to measure article saturation. Publications with a total score of 5 or lower were deemed low quality and excluded from the synthesis. None were excluded as they all met quality assessment criteria. The critical appraisal was independently performed by two reviewers (RP and XL) on each selected research synthesis. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the reviewers or with the assistance of a third team member. The quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the studies.

| Similä et al. (2018) | Gould et al. (2021) | Johansson-Pajala et al. (2022) | Xiang et al. (2021) | Pywell et al. (2020) | Christensen et al. (2021) | Ni (2018) | Choi et al. (2014) | Jarvis et al. (2019) | Gould et al. (2020) | Jiménez et al. (2021) | Andrews et al. (2019) | Averbach and Monin (2022) | Eichenberg et al. (2018) | Gadbois et al. (2022) | Kim et al. (2019) | Choi et al. (2021) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q3 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q4 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q5 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q6 | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Q7 | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Q8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Q9 | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | U | U | Y | U | Y | U | U | U |

| Q10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Q11 | U | U | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | U | U | U | U | U | Y | U |

| JBI scores | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Redefine scores | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

Q1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?

Q2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?

Q3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?

Q4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?

Q5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?

Q6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?

Q7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed?

Q8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented?

Q9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?

Q10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

Q11. Are the criteria for data saturation of results assessed?

Data extraction and synthesis

A specific data extraction matrix was created to collect information from each included study. The first reviewer extracted data from the 17 studies, including the author (year), methodology, qualitative method, geographical location, participants, data analysis, type of mood disorder, technology applied, and main functions (Table 3). In addition, two reviewers identified and extracted the barriers and facilitators of accepting and implementing EMHIs among older adults. The coding process employed in this study was a dual approach, combining inductive and deductive methods. 34 Initially, we applied an inductive coding strategy to identify themes and findings from the qualitative and mixed-methods studies included in this review. This open coding phase aimed to capture a diverse range of barriers and facilitators without predetermined categories. The reviewers (RP and XL) separately read the included literature and quotations to code using Nvivo12plus software. During this process, the reviewers together reviewed and refined iteratively and reflexively. Subsequently, the CFIR 2.0 was introduced as a deductive framework to guide a more structured analysis from innovation, inner setting, outer setting, individuals, and implementation process. We also tailored CFIR 2.0 concepts to align with the specific context of EMHIs among older adults. In the presence of doubt, the reviewers consulted the original literature and conducted a group discussion to reach an agreement. The integration of both inductive and deductive approaches ensured a balanced exploration of the data, capturing the richness of emerging themes while providing a structured framework for analysis within the context of the chosen framework.

Table 3.

Data extraction of included studies.

| Author (year) | Methodology | Qualitative method | Geographical | Participants | Data analysis | Type of mood | Technology applied | Main functions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Similä et al. (2018) | Mixed method | Interviews | Finland | Seven older adults, two healthcare providers | Content analysis | Mental health | Mobile apps | Self-guided platforms |

| 2 | Gould et al. (2021) | Mixed method | Interviews | US | 19 older adults | Inductive and deductive methods | Depression | Mobile apps | Self-guided platforms |

| 3 | Johansson-Pajala et al. (2022) | Mixed method | Diaries, logbook, and interviews | Sweden | 28 older adults | Inductive and deductive methods | Loneliness | Web-based platforms | Social networking |

| 4 | Xiang et al. (2021) | Qualitative | Interviews | US | 21 homebound older adults, eight healthcare providers | Grounded theory | Depression | Web-based platforms | Self-guided platforms |

| 5 | Pywell et al. (2020) | Qualitative | Interviews | UK | 10 older adults | Thematic analysis | Mental health | Mobile apps | Self-guided platforms |

| 6 | Christensen et al. (2021) | Qualitative | Interviews | Denmark | 13 older adults, 12 healthcare providers | Thematic analysis | Depression | Videoconference | Synchronous psychotherapy |

| 7 | Ni (2018) | Mixed method | Textual data analysis | US | 47 older adults | Grounded theory | Depression | Web-based platforms | Self-guided platforms |

| 8 | Choi et al. (2014) | Qualitative | Interviews | US | 12 healthcare providers, 42 older adults | Thematic analysis | Depression | Videoconference | Synchronous psychotherapy |

| 9 | Jarvis et al. (2019) | Qualitative | Interviews | South Africa | 13 older adults | Content analysis | Loneliness | Mobile apps | Social networking |

| 10 | Gould et al. (2020) | Mixed method | Interviews | US | 79 older adults | Thematic analysis | Mental health | Web-based platforms; mobile apps; and others | Self-guided platforms |

| 11 | Jiménez et al. (2021) | Qualitative | Interviews | US | Three healthcare providers, two volunteers, 18 older adults | Thematic analysis | Loneliness | Web-based platforms | Social networking |

| 12 | Andrews et al. (2019) | Qualitative | Interviews | UK | 15 older adults | Template analysis | Mental health | Mobile apps | Self-guided platforms |

| 13 | Averbach and Monin (2022) | Mixed method | Interviews | Australia | Seven healthcare providers | Thematic analysis | Wellbeing | Videoconference | Synchronous conference |

| 14 | Eichenberg et al. (2018) | Mixed method | Interviews | Austria | Two older adults, eight healthcare providers | Thematic analysis | Depression | Web-based platforms | Collaborative online care |

| 15 | Gadbois et al. (2022) | Mixed method | Interviews | US | 21 older adults | Content analysis | Loneliness | Web-based platforms | Social networking |

| 16 | Kim et al. (2019) | Qualitative | Interviews | US | 20 healthcare providers | Grounded theory | Depression | Videoconference | Synchronous psychotherapy |

| 17 | Choi et al. (2021) | Qualitative | Interviews | US | 90 older adults | Thematic analysis | Depression | Videoconference | Synchronous psychotherapy |

Results

Study characteristics

The review comprised 17 research studies.35–51 Of the papers, nine were qualitative studies, and eight were mixed-method studies with an analysis of qualitative data. The sample size ranged from 2 to 90. Among the 17 studies, nine were from the United States, and the other eight were from the UK, Australia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, South Africa, and Austria, respectively. The psychological issues addressed in the study were depression (n = 8, 47%), mental health (n = 4, 24%), loneliness (n = 4, 24%), and wellbeing (n = 1, 6%). The technology applied included web-based platforms, mobile apps, and videoconferences. The main functions were self-guided platforms, social networking, synchronous psychotherapy or conferences, and collaborative online care. Detailed information about these studies is given in Table 3.

Barriers and facilitators

See Table 4.

Table 4.

Barriers and facilitators.

| Domains | Constructs | Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Technical challenges | Barriers: generic designs, complex user interface; human–computer interaction challenges; usability issues | 35,38–44,46–51 |

| Optimized functions and contents | Barriers: unengaging and irrelevant content; long self-study modules; problematic self-diagnose; uninteresting text communication; reluctance to interact with strangers; non-anonymity; one-way call Facilitators: personalization; real-life stories; fit contents; longer therapy sessions |

35,36,38,39,41,42,48–51 | |

| Security and privacy | Barriers: lack of confidence and trust; hack and compromise of data; skepticism Facilitators: clear credentials; anonymity; robust access control mechanisms; transparent permission management |

35,38–40,43,45,48, 50,51 | |

| Outer setting | Community engagement and partnerships | Barriers: lack of reliable recommendation Facilitators: community engagement; collaboration with the aging-service network; media recommendation |

37,38,45,48 |

| Financing | Barriers: absence of financial compensation and reimbursement Facilitators: appropriate financial compensation |

45,47 | |

| Inner Setting | Leadership engagement | Facilitators: managerial leadership's recognition and attention; establish realistic goals and strategic actions | 45,47 |

| Available resources | Facilitators: stable internet access; available devices; enough human resources and infrastructural | 36,38–43,45,47–51 | |

| Incompatibility | Barriers: prioritized chronic illness, pain, medications, and other things; lacking energy or feeling fatigued; overwhelmed with other programs | 38,45,49,50 | |

| Intergenerational support | Facilitators: monitoring, feedback, and timely technical and psychological assistance for family members | 40,47,49 | |

| Training and guidance | Facilitators: technology training and guidance for older adults; specialized workflow training and technology guidance for healthcare providers; on-call expertise training for volunteers | 35–51 | |

| Individuals (older adults) | Perceptions | Barriers: misconceptions and stigma toward depression; fear and skepticism toward technology; bias | 35,37–39,41,45,48, 50,51 |

| Capability | Barriers: low digital self-efficacy; physical deficits; low financial competency | 35–51 | |

| Motivation | Facilitators: perceived benefits; self-reliant determination | 35–51 | |

| Individuals (healthcare providers) | Perceptions | Barriers: skeptical; stereotype | 39,45,47,49,50 |

| Capability | Barriers: low digital literacy and online treatment competency; limited knowledge of lay or volunteers Facilitators: coaching agreement and training agreement |

39,45,47,49,50 | |

| Motivation | Barriers: ineffective; decreased payment; heavy workload Facilitators: perceive benefits; performance review; reduce readmission and rehospitalization |

39,45,47,49,50 | |

| Implementation Process | Recruit | Barriers: recruiting clients and volunteer challenges | 40,45 |

| External assistance | Barriers: concerns about burdening the supporters; uncertain communication frequency Facilitators: tailored feedback; therapist guidance |

35–51 | |

| Team | Facilitators: coordinators or volunteers engage; technicians’ help; role clarity and job functions | 43,45,46 |

Innovation

Technical challenges: Technical challenges were reported in 14 studies.35,38–44,46–51 Some applications or website programs adopt generic designs for intervention that are not tailored to the specific needs of older adults, resulting in complex user interfaces.35,40–44,46,48–52 For example, small screens and keyboards, low color image saturation, unsuitable volume, difficult-to-use function buttons, complex installation or login, and frequent updates. Besides, older adults would face challenges in human–computer interaction, such as difficulties in navigating, getting backward, reviewing previous content, and typing long answers in response to questions after practice.42,48,50,53 In videoconferences, programs usually used Zoom or Skype as platforms.37–39,46,47 Though older adults were relatively familiar with those tools, they still faced usability issues, like screen freeze, audio delays, unstable networks, and interruptions in transmission.38,39 Particularly, abrupt disruptions seemed to diminish the clinical focus of the conversation and distracted stakeholders.39,46

Optimized functions and contents: Ten studies identified many barriers and facilitators to intervention design.35,36,38,39,41,42,48–51 EMHIs serve various functions to cater to users’ diverse needs, encompassing self-guided platforms, social network platforms, and synchronous psychotherapy videoconferences. (1) Self-guided platforms offer pre-recorded courses and practices for users to study independently. Each older adult accessed the same course, prompting a desire for more personalization and feedback.35,42,43,48–51 Besides, the contents should fit common problems and challenges in old age, such as chronic disability challenges, major life event transitions, loneliness and social isolation, family relationships, financial constraints and housing stability, and early life trauma. 50 Unengaging and irrelevant program content makes it difficult to empathize and engage.45,50 Some older adults noted a preference for real-life stories as intervention content. 50 Long modules might lead to fatigue and poor concentration,49–51 while sufficiently short and easy to exercise could motivate older adults to apply learned skills to real-life situations.38,42,50 In addition, some older adults highlighted potential issues with using technology for self-diagnosis, as it could lead to false beliefs about rare or extreme conditions. 35 (2) Social networking platforms involved social conversations through videoconference41,44–46 or creating a virtual community component to post likes, comments, and storytelling.42,44 Older adults could share experiences, get social support, and lessen emotional pressures.44,49 However, current virtual community components were perceived as complex to use, with issues such as uninteresting text communication, reluctance to interact with strangers, and non-anonymity leading to stigmatization.42,46 (3) Synchronous psychotherapy or conference: A notable barrier to synchronous psychotherapy videoconference related to therapist’ call schedules. While the one-way call feature might benefit the organization, it also presents limitations that counter the concept of person-centered mental health care. Patients expressed dissatisfaction with the inability to call their providers freely.39,48 Besides, some older adults preferred longer therapy sessions and duration of treatment to maximize benefit.36–38

Privacy and security: Privacy and security concerns emerged prominently across nine studies.35,38–40,43,45,48,50,51 Older individuals expressed a lack of confidence in data protection, fearing that their data could be hacked or compromised. Additionally, skepticism arose regarding whether real doctors were behind the screen.38,39,48 Some studies showed older adults were reluctant to download apps or access websites unless these tools had clear credentials. 48 Furthermore, the presence of informal or formal caregivers, leading to a lack of privacy, posed a barrier to discussing depression, as therapists struggled to find the space and time to be alone with their clients. 38 To address these privacy concerns, certain studies underscored the importance of incorporating anonymity, robust access control mechanisms, and transparent permission management into EMHIs.43,48,50

Outer setting

Community engagement and partnerships: Four studies highlighted referrals from trusted facilitators could effectively scale up EMHIs.37,38,45,48 Relying solely on researchers to promote EMHIs was deemed insufficient. 48 Given the scarcity of home-based psychotherapy programs in the community, community healthcare workers were pleased to refer their clients to EMHIs.37,38 Aging service network agencies had established infrastructure and were already supporting the needs of homebound older adults.37,38,45 Leveraging their existing systems could facilitate the integration of EMHIs into the overall care framework. Moreover, in one study, older adults highlighted the potential impact of media coverage, suggesting that if journalists recommended a new mental health app on platforms like BBC, it could generate interest and engagement. 48

Financing: The absence of financial compensation and reimbursement was a major deterrent for healthcare agencies adopting or expanding EMHIs in regular practice (n = 2).45,47 Agencies should have funds to purchase program materials, subsidize healthcare providers, and pay for program coordinators. Another study also showed that appropriate financial compensation for healthcare providers could offset job stress. 47

Inner setting

Leadership engagement: Two studies reported that effective implementation and sustaining EMHIs relied heavily on managerial leadership's recognition and attention.45,47 Some healthcare providers might initially doubt the effectiveness of EMHIs. Leadership could reframe thinking and convince them that changes were not only imperative but achievable. 47 Another study emphasized establishing realistic goals and strategic actions would ensure healthcare providers prioritize program goals. 45

Available resources: Thirteen studies emphasized that resources were vital.36,38–43,45,47–51 Ensuring stable internet access and devices were essential for low-income and homebound older adults. Besides, enough human resources and infrastructure were prominent for healthcare agencies to implement and support EMHIs. 47

Incompatibility: Four studies show that some older adults prioritized chronic illness, pain, medications, and other things in their lives, which made it challenging to participate in EMHI programs.38,45,49,50 Besides, lacking energy or feeling fatigued led to refusal of treatment for depression.38,45,49,50 On the other hand, healthcare agencies acknowledged that they were overwhelmed with other programs and did not have the staff and resources to implement and support a new program. 47

Intergenerational support: The successful implementation of EMHIs required intergenerational support (n = 3).40,47,49 Family members could monitor the effectiveness of the intervention, provide feedback to healthcare professionals, and provide timely technical and psychological assistance to older adults.

Training and guidance: All 17 studies reported that technology training and guidance during the initial training would encourage more exploration of EMHIs.35–51 Older users might be hesitant to make mistakes or press the wrong buttons, leading to a reluctance to explore the technological tools fully. The provision of training effectively overcame this hesitancy.41–43,45,48–51 Besides, specialized workflow training and technology guidance for healthcare providers could improve work efficiency and comfort.36,38,39,41,45,49,50 Furthermore, volunteers and coordinators have limited medical knowledge, and there was a need to train them in on-call expertise. 45

Individuals

Older adults: Perceptions. Nine studies highlighted older adults’ negative perceptions as essential barriers.35,37–39,41,45,48,50,51 First, misconceptions about psychological problems and stigma made older adults reluctant to seek help. They mistakenly believed that mental problems were personal issues, a long-term lifestyle experience, and a result of aging. Second, fear and skepticism toward technology might affect its acceptance. 35 Third, some older adults were biased against EMHIs, with concerns over efficacy, security, and usability.

Capability. Low digital self-efficacy was the main barrier to adopting EMHIs by older adults (n = 17).35–51 Besides, cognitive, sensory, and motor deficits might reduce their ability to use EMHIs.35,38,49,50 Moreover, older adults with low financial competency usually made treating mental disorders a low priority. 38

Motivation. Perceived benefits motivated older adults to engage in interventions, as evidenced by 17 studies.35–51 Participants felt they would stop using the intervention if they did not make enough progress.41,48 One study pointed out that the determination to be self-reliant motivates them to engage with technology to support mental health. 45 Especially, long-term benefits were essential in encouraging older adults to continue participating in EMHIs. 50

Healthcare providers: Perceptions. Five studies reported that healthcare providers’ attitudes and perceptions would influence the implementation.39,45,47,49,50 Skepticism about the efficacy of EMHIs and stereotypes that older adults do not use technology potentially impeded recommendation.39,47,50

Capability. Digital literacy and competency among healthcare providers were essential for smooth interventions and adequate support (n = 5).39,45,47,49,50 One study mentioned that therapists hesitated to use EMHIs because their ability to communicate with patients in face-to-face counseling was higher than in virtual (lack of objective micro-information in virtual visits). 39 In addition, some lay or trained volunteers were employed as providers in the team. However, their medical knowledge and technical solutions were limited. 45

Motivation. When perceiving benefits in patient care, healthcare providers became EMHI supporters.39,45,47,49,50 Meanwhile, EMHI utilization as part of a measurable performance review and reduced readmission and rehospitalization could increase motivation. 47 In contrast, providers might reduce patient recommendations or stop offering EMHI if they felt the intervention was ineffective, decreased payment, or had a heavy workload.39,45,47,50

Implementation process

Recruit: Recruiting participants and volunteers was the most significant challenge encountered during implementation (n = 2).40,45 Organizations initially had difficulty identifying older adults interested in participating in EMHIs. 45

External assistance: Seventeen studies reported effective EMHIs need regular professional guidance.35–51 Therapists could improve adherence by providing tailored feedback on reflections, active reminders, and weekly messages.37,39,42,48,50,51 Besides, therapist guidance was a reliable resource for older individuals to decrease electronic distrust and facilitate usage. However, older adults did not seek help because of concerns about burdening the supporter. They also described uncertain communication frequency, which acted as barriers to effective utilization.42,50

Team: Three studies highlighted staffing and division of duties would facilitate implementation.43,45,46 Low digital literacy was common among older adults, contributing to significant time spent recruiting participants, fielding questions, and supporting participants. Therefore, a part-time program coordinator or volunteer was critical to successful implementation and operation.43,45,46 Besides, technicians could deliver, test, and install the EMHI equipment for older people. 43

Discussion

We identify and synthesize barriers and facilitators to accepting and implementing EMHIs among older adults: (1) innovation: technology challenges, optimized functions and contents, security and privacy; (2) outer setting: community engagement and partnerships, and financing; (3) inner setting: leadership engagement, available resources, incompatibility, intergenerational support, training and guidance; (4) individuals: perceptions, capability, motivation of older adults and healthcare providers; and (5) implementation process: recruit, external assistance, team.

In Table 5, we provide recommendations and future implications based on the summarized barriers and contributing factors in order to improve the adaptation, optimization, and expansion of EMIS for older adults in the future. Besides, we also highlight some points as follows.

Table 5.

Recommendation and implication for future.

| Recommendation and implication for future | |

| Co-design and human-centered design | Prioritize user-centric design, involving older adults in the process. |

| Optimized functions and contents | Make sufficiently short, easy to exercise, and real-life story content. Emphasize personalized content, interactions, and machine learning approach. Create interactive modules for active user participation, fostering a sense of agency and control. Enhance features for easier interaction and controlled engagement. |

| Prioritize privacy and anonymity | Provide robust access control mechanisms, transparent permission management, and anonymization. |

| Supportive training and assistance | Include training and ongoing assistance to overcome technical barriers and address computer literacy. |

| Reliable involvement | Encourage the participation of communities, aging service network organizations, media channels, intergenerational support, etc. |

| Leveraging the core elements of EMHI sustainability | Policy, funds, resources, and leadership initiation should be considered. |

| Demonstrate benefits to older users | Use objective indicators and visual data tables to demonstrate mental health improvements in older adults. |

| Provide positive feedback | Offer positive feedback and acknowledgment to reinforce user engagement. |

| Engage healthcare providers | Implement local consensus discussions, educational meetings, and demonstrations to engage healthcare providers. |

| Enhance healthcare providers’ competence | Address workflow confusion and improve competence and teamwork among healthcare providers to support EMHI implementation. |

| Clarify role functions and develop support protocols for team | Create and disseminate clear practice guidelines specifying monitoring frequency, compliance measures, and issue handling. |

| Targeted recruitment strategies | Use e-mail addresses to reach receptive older adults with technology experience or interest. |

| Role clarity and job functions | Make clear roles and functions of healthcare providers, coordinators, telehealth technicians, and volunteers. |

EMHIs: electronic mental health interventions.

Innovation

While computer literacy and technological skills are not new barriers to older adults, they remain important factors in ensuring continued engagement. The main reason is the absence of considering age adaptations in design. Co-design and human-centered design are practical solutions to improve the user experience by including older users in the research process, respecting their psychophysiological needs, and focusing on their behavioral and personality traits.54,55 Per our results, all studies mention that EMHIs must also include supportive training and consistent external assistance to alleviate technical barriers. Supportive training equips older persons with the necessary skills, and constant external help provides continuous support to meet any challenges that may arise. 50

Our results emphasized that achieving personalization in interventions is particularly important. Personalization is a purposeful variation between individuals in interventions’ therapeutic elements or structure. 56 According to Hornstein's study, personalized content and communication with the user are particularly popular. And personalization via decision rules and user choice were the most used mechanisms. 56 Additionally, machine learning emerged as a promising approach, leveraging algorithms to adjust the difficulty of exercises based on user input, change the type of content, and modify the frequency of interactions based on user responses. 56 Besides, making sufficiently short, easy to exercise, and real-life story content is essential. Furukawa et al. 57 did an individual participant data component network meta-analysis of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) trials for depression. The results showed that iCBT packages target relieving depression that might include behavioral activation but not relaxation and cognitive restructuring. Researchers need to simplify the current intervention package using more efficacious and less burdensome intervention components.

To optimize the functionality of virtual communities, leveraging voice input and handwriting features presents potential remedies for minimizing reliance on typing. Additionally, to foster progressive and controlled interactions within the community, consider incorporating features like icebreaker activities, interest groups, or private messaging options. These elements contribute to cultivating a sense of common purpose or shared goals among community members, promoting sustained engagement. 58 By prioritizing these elements, the virtual community can establish a secure, inclusive environment conducive to meaningful and active participation.

Privacy is more important for older adults who experience stigma or reluctance to help-seeking. Robust access control mechanisms, transparent permission management, and anonymization can effectively address privacy concerns.43,48,50 It is worth emphasizing that social forums with many users should be anonymous, using pseudonyms or avatars to bolster anonymity, and reinforcing the platform's commitment to confidentiality and privacy. Videoconferences with therapists can be public with each other to create a therapeutic alliance and capture more micro-expressions.

Inner and outer setting

The core of sustaining and expanding EMHIs includes funds, resources, leadership initiation, and multi-party involvement. 19 This aligns with a previous study that emphasized the necessity for policy changes at both state and federal levels to effectively address the burden on providers. 59 Some countries’ governments have recognized the potential of EMHIs and have integrated telepsychiatry services into their healthcare frameworks. 59 We believe policies in this area can evolve rapidly as digital health continues to play an increasingly significant role in healthcare delivery.

Although only two studies mentioned intergenerational support as facilitators. However, we believe that future studies should focus on family members’ role in EMHIs. Prior research has examined the positive effect of the peer support component,53,60 and lay counselors (peers, family members, friends, and volunteers) could fill the professional geriatric mental health workforce shortage gap. 61 Clarify how family members effectively monitor the intervention, provide feedback to healthcare providers, and provide timely technical and psychological assistance to older adults.

Individual

The individual domain covers intrinsic factors pertaining to stakeholders’ perception, competency, and motivation. Older adults are typically the main population in the “digital divide.” 62 The reason may be the social context. They grew up when digital resources and psychological therapies were scarce or unavailable, and developed a stoic and misguided attitude toward mental health. 62 Therefore, we have re-emphasized the need for user-friendly designs. Besides, targeted psychological and technical education at the outset of the intervention equips older adults with the skills and information to take ownership of their mental health journey. And share positive stories of older adults who benefited from EMHIs with users.

According to our results, we know that older adults need to perceive the benefits of EMHIs. In addition to self-conscious mood changes in older adults, research points to the possibility of presenting objective indicators. Demonstrate continued improvement in mental health to older adults using longitudinal or visual data tables. 35 Besides, therapists provide positive feedback and acknowledgment to older adults for accomplishments. Design interactive modules that allow users to actively participate in their mental health journey actively, reinforcing a sense of agency and control.

Another aspect is the competencies, perceptions, and perceived benefits of healthcare providers, consistent with Feijt et al.'s 63 research on healthcare providers’ readiness for EMHIs. To engage healthcare providers, Graham et al. 64 proposed local consensus discussions, educational meetings, presentations, and demonstrations of EMHIs, along with stressing the benefits of EMHIs implementation and data security safeguards.

Implementation process

Guided interventions typically have higher engagement than unguided interventions. A previous RCT study (n = 433) indicated that either therapist-guided or self-management iCBT might significantly reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression in older adults. 65 But our qualitative results indicated older adults need healthcare providers to provide emotional support, build trusting therapeutic relationships, and improve adherence to websites and apps.

It is suggested that healthcare providers’ competence and teamwork are critical, but inevitably there is workflow confusion among non-professionals, volunteers, and even therapists. Studies have also shown that developing support protocols for providers and teams can improve productivity. Develop and disseminate clear and consistent practice guidelines that specify the frequency of monitoring the use and results of EMHIs, measures of consumer compliance (e.g., daily or weekly logins), criteria for successful completion of EMHIs, and the handling of any issues during the monitoring of EMHIs. 66

Not all older people are receptive to EMHIs, and targeted recruitment strategies are the most successful. Using e-mail addresses to contact self-identified potential participants directly. 45 The most appropriate participants were homebound older adults with experience using technology or a strong interest in developing mental skills. 45

Role clarity and job functions could reduce workload and increase efficiency. Healthcare providers should offer assistance, services, and feedback to older adults. Coordinators ought to oversee project implementation by organizing, managing, and communicating. Telehealth technicians and volunteers could deliver, test, and install the EMHI equipment for older people.37,39

Limitations

This systematic review had several limitations. First, we did not search for grey literature or research published in languages other than English, which may have missed some valuable information. Second, we identified barriers only from older adults who participated in the intervention, which may not represent those who did not or dropped out. Finally, we did not differentiate findings by the category of psychological disorders, as this field is still relatively new, and there were not enough studies for each disorder to provide sufficient information. Although some barriers and facilitators appear common to all mood disorders (e.g. loneliness, depression, anxiety, stress, and distress), some strategies may have nuanced differences. Future studies focusing on EMHIs for different psychological disorders would be more meaningful.

Conclusion

Previous studies have shown the potential of EMHIs to improve older adults’ mental health. To improve the acceptance and implementation of EMHIs, we identified facilitators and barriers across the studies reviewed. Further, we have summarized the key recommendations in discussion. However, revisions are encouraged to allow adequate space for perceptions of various implementation actors and the target group.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241234628 for Barriers and facilitators to acceptance and implementation of eMental-health intervention among older adults: A qualitative systematic review by Ruotong Peng, Xiaoyang Li, Yongzhen Guo, Hongting Ning, Jundan Huang, Dian Jiang, Hui Feng and Qingcai Liu in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076241234628 for Barriers and facilitators to acceptance and implementation of eMental-health intervention among older adults: A qualitative systematic review by Ruotong Peng, Xiaoyang Li, Yongzhen Guo, Hongting Ning, Jundan Huang, Dian Jiang, Hui Feng and Qingcai Liu in DIGITAL HEALTH

Footnotes

Contributorship: QL and HF designed the study question. RP completed the literature search and wrote the draft. RP, XL, and HN selected the articles, extracted the data, and assessed the quality. RP and XL prepared the tables and figures. RP wrote the draft. XL, YG, JH, JD, HF, and QL revised the article and provided critical recommendations on structure and presentation.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Institutional review board approval was not required as this article was a systematic review of the literature and not original research.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2022YFC3601603) and Central South University Research Programme of Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies (Grant No. 2023QYJC034).

Guarantor: Qingcai Liu.

Informed consent: Patient consent was obtained in the studies included in this systematic review. No further consent was requested since this systematic literature review only used publicly available data.

ORCID iD: Ruotong Peng https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5550-4853

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Ageing and Health, 2022.

- 2.Organization WH. Mental health of older adults, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (2017).

- 3.Lloyd CE, Nouwen A, Sartorius N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive disorders in people with type 2 diabetes: results from the international prevalence and treatment of diabetes and depression (INTERPRET-DD) study, a collaborative study carried out in 14 countries. Diabet Med 2018; 35: 760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kastner M, Cardoso R, Lai Y, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for managing multiple high-burden chronic diseases in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cmaj 2018; 190: E1004–E1e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo MS, Chui EWT, Li LW. The longitudinal associations between physical health and mental health among older adults. Aging Ment Health 2020; 24: 1990–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman JT, Frumkin MR, Rodebaugh TLet al. et al. Mhealth assessment and intervention of depression and anxiety in older adults. Harv Rev Psychiatr 2020; 28: 203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wicks P, Stamford J, Grootenhuis MA, et al. Innovations in e-health. Qual Life Res 2014; 23: 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clough BA, Zarean M, Ruane I, et al. Going global: do consumer preferences, attitudes, and barriers to using e-mental health services differ across countries? J Ment Health 2019; 28: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams A, Farhall J, Fossey Eet al. et al. Internet-based interventions to support recovery and self-management: a scoping review of their use by mental health service users and providers together. BMC Psychiatry 2019; 19: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng R, Guo Y, Zhang C, et al. Internet-delivered psychological interventions for older adults with depression: a scoping review. Geriatr Nurs 2023; 55: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pourat N, Padilla-Frausto DI, Chen X, et al. The impact of a primary care telepsychiatry program on outcomes of managed care older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2023; 24: 119–124.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welch V, Ghogomu ET, Barbeau VI, et al. Digital interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness in older adults: an evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst Rev 2023; 19: e1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Read J, Sharpe L, Burton AL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy to prevent the development of depressive disorders in older adults with multimorbidity. J Affect Disord 2020; 264: 464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodarzi Z, Holroyd-Leduc J, Seitz D, et al. Efficacy of virtual interventions for reducing symptoms of depression in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2023; 35: 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibarra F, Baez M, Cernuzzi Let al. et al. A systematic review on technology-supported interventions to improve old-age social wellbeing: loneliness, social isolation, and connectedness. J Healthc Eng 2020; 2020: 2036842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woerner M, Sams N, Nales R, et al. Generational perspectives on technology's role in mental health care: a survey of adults with lived mental health experience. Front Digit Health 2022; 4: 840169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim EH, Gellis ZD, Bradway CKet al. et al. Depression care services and telehealth technology use for homebound elderly in the United States. Aging Ment Health 2019; 23: 1164–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim E, Gellis ZD, Hoak V. Telehealth utilization for chronic illness and depression among home health agencies: a pilot survey. Home Health Care Serv Q 2015; 34: 220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vis C, Mol M, Kleiboer A, et al. Improving implementation of eMental health for mood disorders in routine practice: systematic review of barriers and facilitating factors. JMIR Ment Health 2018; 5: e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martel R, Shepherd M, Goodyear-Smith F. Implementing the routine use of electronic mental health screening for youth in primary care. Systematic review. JMIR Ment Health 2021; 8: e30479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mei C, Vaez K. Success factors for and barriers to integration of electronic mental health screening in primary care. Comput Inform Nurs 2020; 38: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toombs E, Kowatch KR, Dalicandro L, et al. A systematic review of electronic mental health interventions for indigenous youth: results and recommendations. J Telemed Telecare 2021; 27: 539–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borghouts J, Eikey E, Mark G, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions. Systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wildenbos GA, Jaspers MWM, Schijven MPet al. et al. Mobile health for older adult patients: using an aging barriers framework to classify usability problems. Int J Med Inform 2019; 124: 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruse C, Fohn J, Wilson N, et al. Utilization barriers and medical outcomes commensurate with the use of telehealth among older adults. Systematic review. JMIR Med Inform 2020; 8: e20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraaijkamp JJM, van Dam van Isselt EF, Persoon A, et al. Ehealth in geriatric rehabilitation: systematic review of effectiveness, feasibility, and usability. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e24015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAOet al. et al. The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement Sci 2022; 17: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weir NM, Newham R, Dunlop Eet al. et al. Factors influencing national implementation of innovations within community pharmacy: a systematic review applying the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci 2019; 14: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper J, Murphy J, Woods C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing community-based physical activity interventions: a qualitative systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021; 18: 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meshkovska B, Scheller DA, Wendt J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of direct fruit and vegetables provision interventions in kindergartens and schools: a qualitative systematic review applying the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2022; 19: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder D, Luig T, Finch TL, et al. Understanding implementation context and social processes through integrating normalization process theory (NPT) and the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci Commun 2022; 3: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 2019; 7: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batra S, Baker RA, Wang T, et al. Digital health technology for use in patients with serious mental illness: a systematic review of the literature. Med Devices (Auckl) 2017; 10: 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Johnny Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 3 ed. London: Arizona State University, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrews JA, Brown LJ, Hawley MSet al. et al. Older Adults’ perspectives on using digital technology to maintain good mental health: interactive group study. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e11694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Averbach J, Monin J. The impact of a virtual art tour intervention on the emotional well-being of older adults. Gerontologist 2022; 62: 1496–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi NG, Caamano J, Vences K, et al. Acceptability and effects of tele-delivered behavioral activation for depression in low-income homebound older adults: in their own words. Aging Ment Health 2021; 25: 1803–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi NG, Wilson NL, Sirrianni L, et al. Acceptance of home-based telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults: qualitative interviews with the participants and aging-service case managers. Gerontologist 2014; 54: 704–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen LF, Wilson R, Hansen JP, et al. A qualitative study of patients’ and providers’ experiences with the use of videoconferences by older adults with depression. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2021; 30: 427–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eichenberg C, Schott M, Sawyer A, et al. Feasibility and conceptualization of an e-mental health treatment for depression in older adults: mixed-methods study. JMIR Aging 2018; 1: e10973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gadbois EA, Jimenez F, Brazier JF, et al. Findings from talking tech: a technology training pilot intervention to reduce loneliness and social isolation among homebound older adults. Innov Aging 2022; 6: igac040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gould CE, Carlson C, Ma F, et al. Effects of mobile app-based intervention for depression in middle-aged and older adults: mixed methods feasibility study. JMIR Form Res 2021; 5: e25808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gould CE, Loup J, Kuhn E, et al. Technology use and preferences for mental health self-management interventions among older veterans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020; 35: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarvis MA, Chipps J, Padmanabhanunni A. “This phone saved my life”: older persons’ experiences and appraisals of an mHealth intervention aimed at addressing loneliness. Journal of Psychology in Africa 2019; 29: 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiménez FN, Brazier JF, Davoodi NM, et al. A technology training program to alleviate social isolation and loneliness among homebound older adults: a community case study. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 750609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansson-Pajala RM, Gusdal A, Eklund C, et al. A codesigned web platform for reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: a feasibility study. Inform Health Soc Care 2022: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim E, Gellis ZD, Bradway Cet al. et al. Key determinants to using telehealth technology to serve medically ill and depressed homebound older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work 2019; 62: 451–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pywell J, Vijaykumar S, Dodd Aet al. et al. Barriers to older adults’ uptake of mobile-based mental health interventions. Digit Health 2020; 6: 2055207620905422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Similä H, Immonen M, Toska-Tervola J, et al. Feasibility of mobile mental wellness training for older adults. Geriatr Nurs 2018; 39: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang X, Kayser J, Sun Yet al. et al. Internet-based psychotherapy intervention for depression among older adults receiving home care: qualitative study of participants’ experiences. JMIR Aging 2021; 4: e27630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yiqi N. A mixed-methods approach to exploring engagement in MoodTech: An online CBT intervention for older adults with depression . Master's degree, University of Washington, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gould CE, Zapata AML, Bruce J, et al. Development of a video-delivered relaxation treatment of late-life anxiety for veterans. Int Psychogeriatr 2017; 29: 1633–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tomasino KN, Lattie EG, Ho J, et al. Harnessing peer support in an online intervention for older adults with depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017; 25: 1109–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dukhanin V, Wolff JL, Salmi L, et al. Co-designing an initiative to increase shared access to older adults’ patient portals: stakeholder engagement. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e46146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paluch R, Cerna K, Kirschsieper Det al. et al. Practices of care in participatory design with older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: digitally mediated study. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e45750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hornstein S, Zantvoort K, Lueken U, et al. Personalization strategies in digital mental health interventions: a systematic review and conceptual framework for depressive symptoms. Front Digit Health 2023; 5: 1170002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Furukawa TA, Suganuma A, Ostinelli EG, et al. Dismantling, optimising, and personalising internet cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis using individual participant data. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8: 500–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Connell ME, Haase KR, Grewal KS, et al. Overcoming barriers for older adults to maintain virtual community and social connections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gerontol 2022; 45: 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gentry MT, Lapid MI, Rummans TA. Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019; 27: 109–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Proudfoot J, Parker G, Manicavasagar V, et al. Effects of adjunctive peer support on perceptions of illness control and understanding in an online psychoeducation program for bipolar disorder: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2012; 142: 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen GJ, Kunik ME, Marti CNet al. et al. Cost-effectiveness of tele-delivered behavioral activation by lay counselors for homebound older adults with depression. BMC Psychiatry 2022; 22: 648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jun W. A study on cause analysis of digital divide among older people in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feijt MA, de Kort YAW, Westerink JHDM, et al. Assessing professionals’ adoption readiness for eMental health: development and validation of the eMental health adoption readiness scale. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e28518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hermes EDA, Burrone L, Heapy A, et al. Beliefs and attitudes about the dissemination and implementation of internet-based self-care programs in a large integrated healthcare system. Adm Policy Ment Health 2019; 46: 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Titov N, Fogliati VJ, Staples LG, et al. Treating anxiety and depression in older adults: randomised controlled trial comparing guided v. self-guided internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy. BJPsych Open 2016; 2: 50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lattie EG, Graham AK, Hadjistavropoulos HD, et al. Guidance on defining the scope and development of text-based coaching protocols for digital mental health interventions. Digit Health 2019; 5: 2055207619896145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241234628 for Barriers and facilitators to acceptance and implementation of eMental-health intervention among older adults: A qualitative systematic review by Ruotong Peng, Xiaoyang Li, Yongzhen Guo, Hongting Ning, Jundan Huang, Dian Jiang, Hui Feng and Qingcai Liu in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076241234628 for Barriers and facilitators to acceptance and implementation of eMental-health intervention among older adults: A qualitative systematic review by Ruotong Peng, Xiaoyang Li, Yongzhen Guo, Hongting Ning, Jundan Huang, Dian Jiang, Hui Feng and Qingcai Liu in DIGITAL HEALTH