ABSTRACT

Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) for older people play an important and unique role in multidrug-resistant organism transmission. Herein, we investigated the genetic characteristics of mobile colistin resistance gene (mcr-1)-carrying Escherichia coli strains isolated from wastewater of LTCFs in Shanghai. Antimicrobial susceptibility test was carried out by agar dilution methods. Whole-genome sequencing and plasmid sequencing were conducted, and resistance genes and sequence types of colistin in E. coli isolates were analyzed. Core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) analysis was performed by the Ridom SeqSphere+ software. Phylogenetic tree through the maximum likelihood method was constructed by MEGA X. Out of 306 isolates, only 1 E. coli named ECSJ33 was found, and the plasmid pECSJ33 from ECSJ33 harbored the mcr-1 gene that was located with 59,080 bp belonging to IncI2 type. The plasmid pECSJ33 was capable of conjugation with an efficiency of 2.9 × 10−2. Bioinformatic analysis indicated pECSJ33 shared backbone with the previously reported mcr-1-harboring pHNGDF93 isolated from fish source. Moreover, the cgMLST analysis revealed that ECSJ33 belongs to different lineages from those reported from previous E. coli strains but shared high similarity to NCTC11129 in cluster 11. The phylogenetic tree revealed MCR-1 of ECSJ33 in this study was mostly of animal food origin and that they were closely related. Our study firstly reports detection of genome sequence of a multidrug-resistant mcr-1-harboring E. coli ST155 from wastewater of LTCF source in China. The data may prove that the plasmid pECSJ33 belongs to food origin and help to understand the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms and genomic features of colistin resistance under One Health approach.

IMPORTANCE

One Escherichia coli named ECSJ33 was found from wastewater of a long-term care facility (LTCF) and the plasmid pECSJ33 from ECSJ33 harbored the mobile colistin resistance gene (mcr-1) that was located with 59,080 bp belonging to IncI2 type, which was capable of conjugation with an efficiency of 2.9 × 10-2. This paper firstly reports an mcr-1-carrying E. coli strain ST155 isolated from LTCF in China. Comparative genomics analysis indicated pECSJ33 shared backbone with the previously reported mcr-1-harboring pHNGDF93 isolated from fish source. The phylogenetic tree revealed MCR-1 protein of ECSJ33 in this study was mostly of animal food origin and that they were closely related. Therefore, the pECSJ33 could be considered as food-origin transmission mcr-1-harboring plasmid.

KEYWORDS: wastewater, long-term-care facility, mcr-1, plasmid, Escherichia coli ST155

INTRODUCTION

Enterobacteriaceae isolates, which carry plasmid-borne carbapenemase and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes (1), could generate resistance to multiple drugs and contribute to the spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria in human populations. The frequent usage of β-lactams and carbapenems over the past several decades has led to the increased use of colistin, which is considered the last therapeutic option for treating infections caused by such organisms (2, 3). Currently, the efficacy of colistin has been challenged by the emergence of plasmid-mediated mobile colistin resistance gene (mcr-1), which was found in Enterobacteriaceae in 2016 (4), and has since been disseminated in animals, meat products, humans (both fecal carriage and infections), and the environment in over 50 countries, covering six continents (5–8). In China, colistin has been adopted for treating carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) infections since 2018 (9), thereby increasing the potential risk of the dissemination of mcr-1. Therefore, to effectively control mcr-1 gene prevalence from human, animal, and environment sources is crucial.

The spread of colistin resistance is driven by a number of factors, including the overuse and misuse of colistin, the lack of new antibiotics in development, and the dissemination of colistin resistance genes through horizontal gene transfer (10–12). Hospital wastewater is known to be a reservoir for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes, and its contamination with mcr-1-harboring bacteria is a serious public health concern (13, 14). Furthermore, residents of long-term care facilities (LTCFs) are recognized as being at increased risk of colonization/infection with MDR organisms because of age-associated morbidities, exposure to recurrent antibiotic courses, and frequent referral to and from acute care hospitals (15). LTCFs were reported as the carriers of CRE, most were ESBL and Klebsiella pneumoniae (16–18). The discharge of wastewater into the environment can facilitate the spread of these bacteria and genes. Therefore, the detection and characterization of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in LTCF wastewater are crucial for understanding the spread of resistance genes and developing effective strategies for their control. In recent years, there has been growing awareness of antimicrobial resistance pollution in aquatic environments, leading to increased research on the presence and coexistence of antibiotics, and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) (19, 20).

Shanghai is one of the most populous and economically important cities in China, with a large concentration of industrial and commercial activities. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in Shanghai receive effluent from various sources, including hospitals, food-processing industries, and residential areas, making them potential hotspots for the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. Several studies have reported the presence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli isolates from wastewater in global and other regions of China (21–24); however, there is limited information on the prevalence and genetic diversity of mcr-1 in E. coli isolated from LTCF wastewater in Shanghai.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence, genetic characteristics, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of mcr-1-harboring E. coli isolated from LTCF wastewater in Shanghai, China. We also aimed to assess the potential risk of transmission of mcr-1-harboring E. coli from wastewater to humans and the environment. Our findings will provide valuable insights into the epidemiology and ecology of mcr-1-harboring E. coli in wastewater and the potential implications for public health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and strain isolation

A total of 306 medical institutions as sentinel surveillance port were randomly selected in 15 districts in Shanghai during May to August 2022. The sampling point is set at the sewage outlet of the medical institution, and the sampling point management file shall be established, including the sampling name, Global Position System and number of the sampling point, and the sampling frequency and pollution factors. The sampling container is a 500 mL sterilized sampling bottle, which is rinsed three times with a water sample before sampling, followed by direct sampling at the sampling depth. Water samples (50 mL each) were collected aseptically and kept in 4°C during transportation and sent to the laboratory within 4 h of collection. After sedimentation by gravity, the supernatants were filtered using membrane filters and subsequently placed into Enterobacteriaceae enrichment broth (Trypticase Soy Broth, COMAGAL Microbial Technology, Shanghai, China) for overnight enrichment. Next, 200 µL of bacterial solutions was inoculated into MacConkey agar medium (COMAGAL Microbial Technology, Shanghai, China) containing 2 µg/mL colistin overnight at 37°C. The single colonies were then identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time of flight mass spectrometry using the VITEK MS system (BioMérieux Shanghai Co. Limited). The score cut-off of ≥2.000 was applied for species-level identification according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

Detection of colistin-resistant E. coli and screening of mcr-1 to mcr-10 gene

The positive red colonies were further confirmed and selected by amplifying the mcr-1 to mcr-10 gene via real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Basic clinical data, including gender, age, and date of isolation, were collected for patients from whom the mcr-1-harboring strains were isolated. The genomic DNA from each of the strains was extracted by boiling and freeze-thawing processes, and the resulting supernatant was used as the template. The specific primer for mcr-1 used in this study was reported previously (25). The primers of mcr-2 to mcr-5 were derived as reported by Rebelo et al. (26). As for mcr-6 to mcr-10, the primers were derived from Maria et al. (27).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

This testing was performed by the broth microdilution method using 28 antimicrobial agents (Shanghai Fosun Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China) including ampicillin (AMP), ampicillin/sulbactam 2:1 ratio (AMS), tetracycline (TET), chloramphenicol (CHL), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT), cefazolin (CFZ), cefotaxime (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefoxitin (CFX), gentamicin (GEN), imipenem (IMP), nalidixic acid (NAL), azithromycin (AZI), tigecycline (TIG), ciprofloxacin (CIP), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC), cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (CTC), ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (CAC), colistin (CT), aztreonam (ATM), cefuroxime (CXM), amikacin (AMI), cefepime (CPM), meropenem (MEM), levofloxacin (LEV), ertapenem (ETP), ceftazidime/avibactam (CZA), streptomycin (STR), and norfloxacin (NOR). E. coli ATCC 25922 strain was used as quality control. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of colistin were determined and interpreted using the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines with 2 µg/mL for colistin resistance (https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.eucast.org%2Ffileadmin%2Fsrc%2Fmedia%2FPDFs%2FEUCAST_files%2FBreakpoint_tables%2Fv_13.0_Breakpoint_Tables.xlsx&wdOrigin = BROWSELINK). Strains resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobial agents were defined as multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Conjugation assay

To investigate whether the mcr-1 gene was present on a transferable plasmid, we performed plasmid conjugation transfer experiments using E. coli C600 (rifampicin resistant) as the recipient. The donor and recipient bacterium were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium at 37°C until optical densiy of 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.5, and then, the donor/recipient bacterium were mixed at a ratio of 1:3. The mixture was added into 5 mL LB liquid medium incubated for mating for 16–18 h at 37°C. The transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar containing 40 µg/mL rifampicin and 2 µg/mL colistin. Putative transconjugant was confirmed by antimicrobial susceptibility testing and RT-PCR, and the transfer frequency was calculated by transconjugants/donors as previously described (28).

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAGEN genomic DNA purification kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Sequencing libraries were generated using the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). The genome sequencing was then performed with standard protocol and were sequenced with 150 bp paired-end strategy by using the Illumina Novaseq 6000 (Sangon Biotech Company, Shanghai, China). Bacterial genome assembly was proceeding after adapter contamination removal and data filtering by using SPAdes software (version 3.12.3) (29) and A5-miseq to constructed scaffolds and contigs. Function annotation was completed by BLAST search against different databases and were annotated using PATRIC (version 3.6.9).

The assembled contigs were subsequently queried with PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/), PlasmidFinder 2.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/), CARD (The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance, https://card.mcmaster.ca/), and VFDB (Virulence Factors of Pathogenic Bacteria, http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/main.htm) available from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org) for multilocus sequence typing (MLST), plasmid replicon typing, antimicrobial resistance gene identification, and virulence gene identification, respectively. The bacterial species differences and genome-wide similarities were generated by FastANI (Fast Average Nucleotide Identity, version 1.33).

Plasmid sequencing

Plasmid DNA was extracted from E. coli C600 transformants harboring the mcr-1 plasmid with the QIAGEN plasmid miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Plasmid DNA was excised from the gel and purified using the Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega), which was used to prepare sequencing libraries using the Nextera XT DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, USA). Next-generation sequencing analysis of 150 bp paired-end sequencing was performed on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, USA). The contigs obtained after de novo assembly as described above were subjected to gap-closing PCR and Sanger sequencing to determine the complete nucleotide sequence. The obtained sequence data were submitted to the DFAST for annotation. The linear comparison of complete plasmid sequences was created by Easyfig (http://mjsull.github.io/Easyfig/). The plasmid construction map was generated by SnapGene 6.1.2 software (Insightful Science, USA).

Phylogenetic analysis

The complete genomes of mcr-1-positive E. coli (MCRPEC) were used for phylogenetic analysis. The identification of core genes and core genome was performed using Roary, and then the core genomic alignment was used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogeny on MEGA X (Mega Limited, Auckland, New Zealand). The core genome MLST type (cgMLST) analysis was performed by the Ridom SeqSphere+ software (GmbH, Münster, Germany). In E. coli, a cgMLST cluster was defined if having ≤10 non-identical target gene (30). Consequently, 3,179 core genes were used to construct a minimum spanning tree and look for allelic differences.

For MCR-1 protein phylogenetic analysis, the MCR-1 and MCR-1-like proteins’ homologous sequences were extracted from the NCBI through BLASTp search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 30 September 2023), with MCR-1 protein of ECSJ33 in this study obtained from the sequencing data. Aligned sequences of MCR-1 obtained from ClustalW version 2.0 (http://www.clustal.org/) were used to construct a phylogenetic tree through the maximum likelihood method of MEGA X. To confirm the results, 1,000 bootstrap repetitions were used.

Statistical analysis

Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was used for statistical analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical tests were carried out by SPSS v26.0 (IBM, USA).

RESULTS

mcr-1-harboring E. coli isolate detection

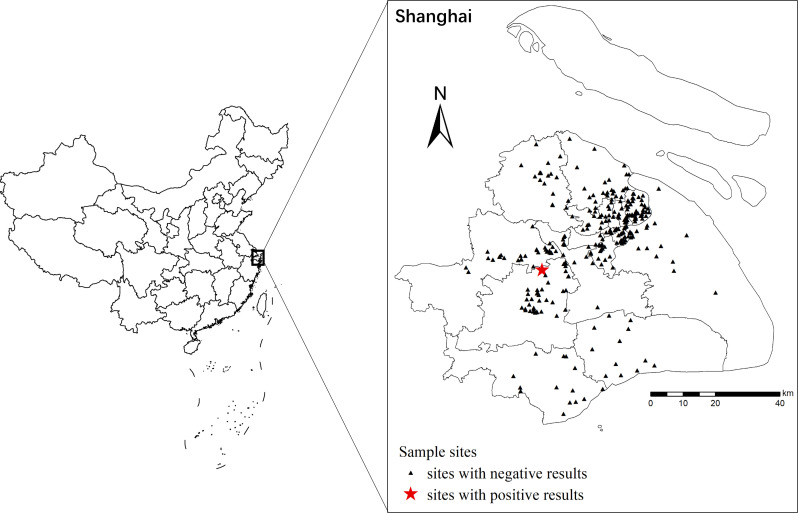

Of the 306 E. coli isolates from hospital wastewater in 15 districts included in this study during May to August 2022, samples were mainly isolated from Songjiang (n = 41, 13.40%), Qingpu (n = 36, 11.76%), and Yangpu (n = 36, 11.76%) (Fig. 1). For the medical institutions, the samples were mainly isolated from private clinics (n = 196, 64.05%), followed by grade IIA hospitals (n = 54, 17.65%) and LTCFs (n = 23, 7.52%). There were significant differences observed on the samples among those facilities (P < 0.05). None of these isolates carried mcr-2 to mcr-10 gene; only the E. coli isolate ECSJ33 isolated from an LTCF located in Songjiang District carried the mcr-1 gene.

Fig 1.

Geographical locations of the sample sites in this study. The sites with negative results were indicated with triangle, while sites with positive results were shown in red. The maps were created using ArcGIS 10.3 software.

Susceptibility to antimicrobial and conjugative isolates

ECSJ33 exhibited colistin resistance at 4 µg/mL, which was considered as the resistance of E. coli according to EUCAST standards (Table 1). Furthermore, ECSJ33 was also found to be resistant to AMP, SXT, CHL, and TET. However, it was found to be susceptible to 15 other common antibiotics, including CIP, CTX, CZA, IMP, ETP, TIG, and others (as shown in Table 1). The result indicated that the mcr-1-harboring plasmid was capable of successful transfer from the donor strain to the recipient strain (E. coli C600). The conjugation of ECSJ33 to E. coli C600 via horizontal transfer was achieved with an average efficiency of 2.9 × 10−2. The transconjugant ECSJ33-T exhibited an MIC value of 4 µg/mL to colistin, which was increased when compared to the recipient E. coli C600 (0.25 µg/mL). That means ECSJ33-T acquired the colistin resistance gene from the donor strain.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the mcr-1-harboring E. coli SJ33 and its transconjugant ECSJ33-Ta identified in this study

| Antibiotic | SJ33 | ECSJ33-T | EC C600 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | Result | MIC | Result | MIC | Result | |

| CIP | 0.25 | S | 1 | R | ≤0.015 | S |

| AMP | >64 | R | >64 | R | 4 | S |

| AMS | 16/8 | I | 16/8 | I | 4/2 | S |

| CT | 4 | I | 4 | I | 0.25 | S |

| CFZ | 4 | I | 4 | R | 2 | S |

| CTX | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | R | ≤0.25 | S |

| CAZ/C | ≤0.25/4 | −b | ≤0.25/4 | − | ≤0.25/4 | − |

| CTX/C | ≤0.125/4 | − | ≤0.125/4 | − | ≤0.125/4 | − |

| CFX | 4 | S | 8 | S | 2 | S |

| CPM | ≤1 | S | ≤1 | S | ≤1 | S |

| CXM | 2 | S | 8 | R | ≤0.5 | S |

| CZA | ≤0.25/4 | S | ≤0.25/4 | S | ≤0.25/4 | S |

| IMP | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S |

| CAZ | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | 0.5 | S |

| AZI | ≤2 | − | ≤2 | − | ≤2 | − |

| ETP | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S |

| SXT | >8/152 | R | >8/152 | R | >8/152 | R |

| NAL | 16 | S | >64 | R | >64 | R |

| CHL | >64 | R | >64 | R | 4 | S |

| GEN | ≤1 | S | ≤1 | R | ≤1 | S |

| TET | >32 | R | 32 | R | ≤1 | S |

| TIG | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S |

| AMI | ≤2 | S | ≤2 | S | ≤2 | S |

| ATM | ≤2 | S | ≤2 | R | ≤2 | S |

| LEV | 0.5 | S | 2 | R | ≤0.125 | S |

| MEM | ≤0.125 | S | ≤0.125 | S | ≤0.125 | S |

| STR | ≤4 | − | ≤4 | − | 8 | − |

| NOR | 1 | S | 4 | R | ≤0.125 | S |

R, resistant; I, intermediate; S, susceptible.

This could not provide the results for the MIC obtained in the study.

Genetic characterization of mcr-1-harboring plasmids

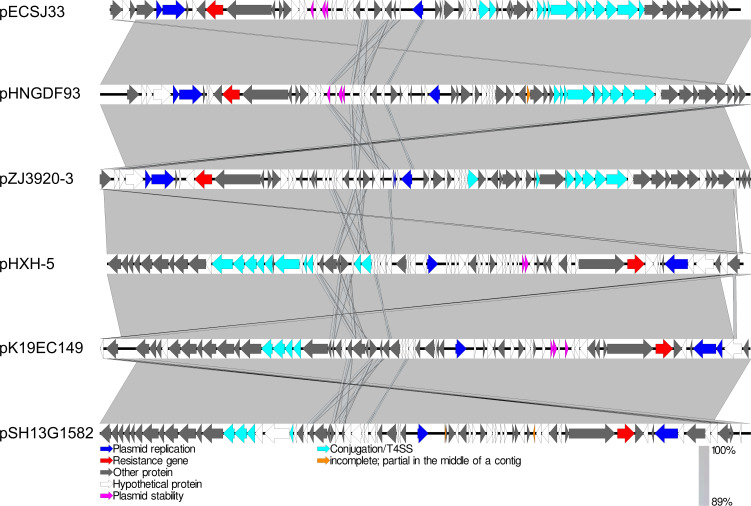

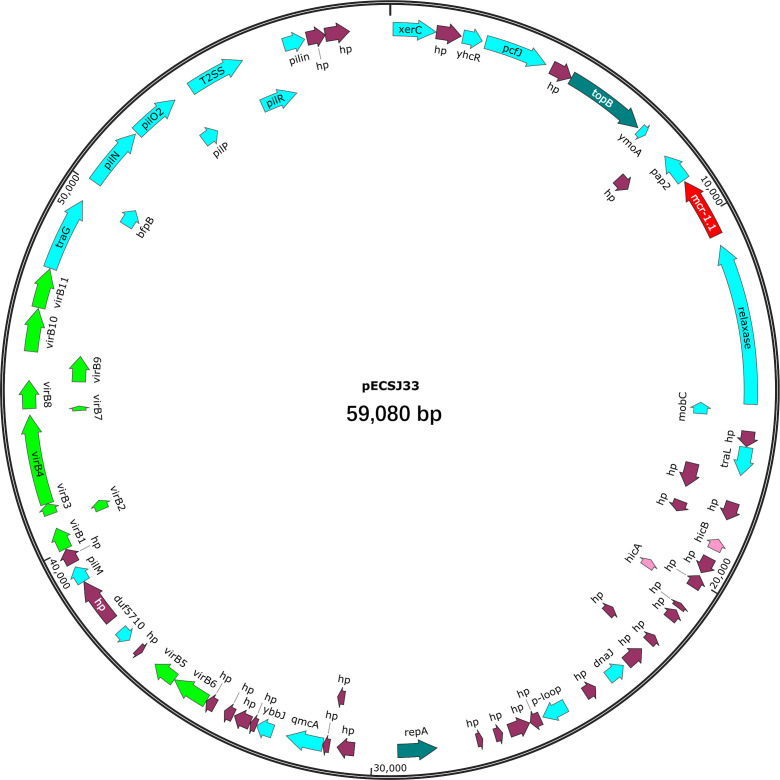

Apart from mcr-1, ECSJ33 was also found to carry resistance genes for blaTEM-135 (β-lactamase), dfrA14 (trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase), qnrS1 (quinolone-resistant protein), and other resistant genes relating to antibiotic efflux pump (cpxA, emrR, emrB, acrE, tolC, msbA, evgA, mdtE). The sequence type (ST) of ECSJ33 identified in this study was ST155. Whole-genome sequencing analysis revealed that the mcr-1 gene was located on a 59,080 bp IncI2 plasmid in pECSJ33 isolate. BLASTn analysis showed that the backbone of the plasmid pECSJ33 (this study) was strikingly similar to (the query cover of 100% and the identities 99%) other previously sequenced mcr-1-harboring plasmids, such as pHNGDF93 from E. coli GDT6F93 (GenBank accession no. MF978388), pHXH-5 from E. coli HXH-5 (GenBank accession no. MH202956), pK19EC149 from E. coli pK19EC149 (GenBank accession no. CP050290), pSH13G1582 from Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SH13G1582 (GenBank accession no. MH522412), and pZJ3920-3 from E. coli ZJ3920 (GenBank accession no. CP020548). In all, the result showed that these mcr-1-harboring plasmids exhibited very high architectural conservation (>89% identity, Fig. 2). Furthermore, the BLAST comparison of these plasmids revealed that their mcr-1 insertion sites differed: pECSJ33, pHNGDF93, and pZJ3920-3 shared the similar sites, while pHXH-5, pK19EC149, and pSH13G1582 had the same insertion sites (Fig. 2). An approximately 2.6 kb mcr-1-pap2 element was identified in the above-mentioned plasmids. The putative conjugal transfer components of pECSJ33 were also detected by using oriTfinder. The vir gene family members encoding VirB1 to VirB11 were identified as belonging to the type IV secretion system (T4SS), as predicted on pECSJ33 (Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Linear comparison of complete plasmid sequences of plasmid E. coli pECSJ33 (this study), pHNGDF93 from E. coli GDT6F93 (GenBank accession no. MF978388), pHXH-5 from E. coli HXH-5 (GenBank accession no. MH202956), pK19EC149 from E. coli pK19EC149 (GenBank accession no. CP050290), pSH13G1582 from Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SH13G1582 (GenBank accession no. MH522412), and pZJ3920-3 from E. coli ZJ3920 (GenBank accession no. CP020548). The arrows represent the position and transcriptional direction of theopen reading frames (ORFs). Resistance gene (mcr-1) is indicated by the red arrow, plasmid replication proteins are indicated in blue, plasmid stability proteins are highlighted in pink arrows, and type IV secretion system genes are indicated by light blue arrows.

Fig 3.

Map of mcr-1-harboring plasmid pECSJ33. The mcr-1 gene is marked in red. The figure was created using SnapGene Viewer software.

Phylogenetic analysis

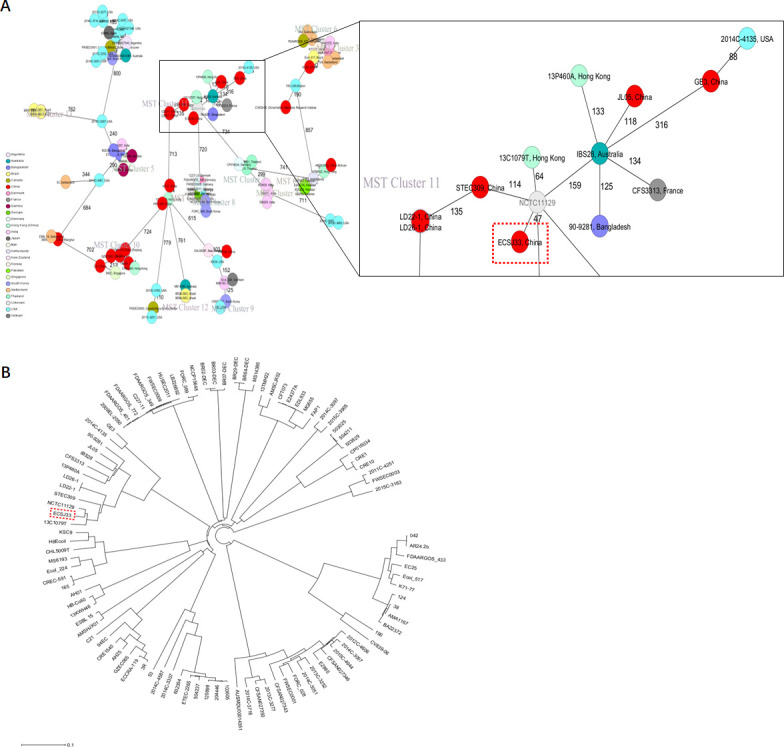

The cgMLST analysis identified 3,179 core genes and was performed for the 101 E. coli isolates including ECSJ33. The minimal spanning tree (MST) showed strains with different sources, and 22 distinct clonal transmission events were observed across 101 genomes. ECSJ33 was found to be highly similar to NCTC11129 strain in cluster 11, with only 47 sites differing from each other (Fig. 4A). Strains clustered by cgMLST also revealed the deep branching and scattered population structure contained in distinct clades, which was broadly classified into distinct phylogenetic lineages (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Phylogenetic analysis. (A) Minimum spanning tree constructed on the basis of cgMLST allelic genes of 101 MCRPEC strains. Each circle depicts an allelic profile based on sequence analysis of 3,179 cgMLST genes. The length of the connecting lines represents the number of target genes with different alleles. Each circle within the tree represents a cgMLST type, with diameters scaled to the number of isolates belonging to that type. Colors represent different isolation countries. Closely related genotypes (<10 alleles difference) are shaded in the same node, and clusters are numbered consecutively. (B) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of 101 MCRPEC strains based on the core genome. The red dashed box indicates ECSJ33 strain.

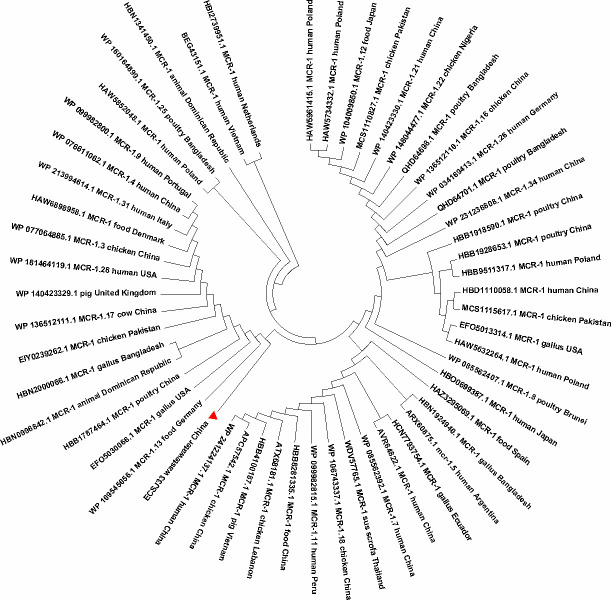

A total of 54 MCR-1 proteins that originated from E. coli (File S1) were categorized for further analysis. In the case of protein acquisition from the NCBI database, above 50% of query coverage was set as the screening point. The set of proteins (File S1), including ECSJ33 strain harboring MCR-1 in this study, was used for phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 5). The sequenced MCR-1 of ECSJ33 in this study clearly showed its genomic confirmation as mcr-1 genes by highly aligning with mcr-1 genes of E. coli as well as other bacterial origins. In addition, the phylogenetic tree showed that ECSJ33 strain in this study was mostly of animal food origin and that they were closely related.

Fig 5.

Phylogeny of 58 MCR-1 proteins of E. coli origin retrieved from the NCBI database. Using amino acid sequences from one E. coli MCR-1 protein in this study (ECSJ33), the BLAST search tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 30 September 2023) was used to retrieve homologous sequences of MCR-1 and MCR-1-like proteins from the NCBI database. MCR-1 and MCR-1-like proteins of E. coli containing LptA and others were among the sequences categorized. Using aligned MCR-1 sequences from ClustalW, the maximum likelihood method of MEGA X was used to create a phylogenetic tree.

DISCUSSION

The emergence and spread of the mcr-1 gene in Enterobacteriaceae, particularly E. coli, represents a significant challenge to public health worldwide. In this study, we report the detection of mcr-1 in E. coli isolated from LTCF wastewater samples in Shanghai, China, highlighting the potential role of wastewater as a reservoir for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The detection of mcr-1 in LTCF wastewater samples is concerning, which is considered a last-resort antibiotic for the treatment of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

Our study suggests a lower prevalence (0.33%, 1/306) of mcr-1 in LTCF wastewater than that reported from other LTCFs in other countries such as Italy (31) and the Netherlands (18). Furthermore, the prevalence was also lower than E. coli strains isolated from human populations in Shanghai (25, 32, 33), and it was not as high as that found in E. coli isolated from hospitalized companion animals (34). Given that those E. coli strain carriers were only detected during the prevalence survey, most carriers remain undetected in Shanghai.

One of the key findings of our study is the identification of a novel mcr-1-harboring plasmid, which we have designated pECSJ33. This plasmid was found in E. coli isolate from an LTCF in Songjiang District in Shanghai and was similar to the previously reported mcr-1-harboring pHNGDF93, which was isolated from fish in Guangdong Province. The phylogenetic tree showed that the MCR-1 protein of ECSJ33 was also found to be similar with MCR-1.13 isolated from food source in Germany (WP 109545655.1). Given this evidence, we speculated that ECSJ33 may have originated via the food chain and integrated into wastewater (8, 35, 36). This highlights the importance of surveillance efforts to monitor the emergence and dissemination of mcr-1 among the elderly in LTCFs, as well as the co-existence of ESBL genes such as blaTEM-135 and mcr-1 gene carrying E. coli, which have been reported globally, particularly in animal source E. coli isolates from food-producing animal in Poland located on IncX4 plasmid (37), from human in Thailand located on IncHI/IncN plasmid (38), and from human in China located on IncI2 plasmid (24). Our study identified, for the first time, the co-existence of blaTEM-135 and mcr-1 from a wastewater source isolate in E. coli in Shanghai. This finding indicates a high risk of disseminating this extensively drug-resistant E. coli, which poses a threat to public health.

The finding of cgMLST and phylogenetic tree revealed that ECSJ33 isolate belonged to the ST155 that was similar to E. coli strain NCTC11129 (GenBank accession no. GCA_900636075.1); the latter was submitted by Wellcome Sanger Institute in 2014 with the accession no. PRJEB6403. However, the mcr-1 gene was absent in NCTC11129, suggesting that the dissemination of mcr-1 in the environment is likely due to the horizontal transfer of the IncI2 plasmid between different E. coli strains rather than clonal expansion of a single mcr-1-positive strain.

Previous studies have shown that wastewater samples like wastewater treatment plants can be a source of multidrug-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in the environment (39, 40). Our study also demonstrates the potential for the spread of mcr-1 from wastewater to human populations. In addition, untreated wastewater may contain high concentrations of antibiotic residues, providing a selective pressure for the emergence and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (41). Therefore, it is important to develop strategies to mitigate the risk of transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from wastewater to human populations.

There are two limitations to this study. Firstly, the mcr-1 prevalence of E. coli isolates was only collected from wastewater samples in Shanghai, China. To obtain more accurate results, it would be beneficial to include isolates from additional sources including human, animal, and food, which could contribute to the dissemination of mcr-1 transmission and spread using the “One Health” approach. Secondly, only one positive E. coli isolate carrying mcr-1 gene was found in this study, which needs to be carried out among more isolates and from more regions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provides evidence for the prevalence and characteristics of mcr-1-positive E. coli isolated from wastewater of LTCFs in Shanghai, China. The mcr-1 on an IncI2 plasmid E. coli strain found in our study was also detected to carry other multiple resistance genes, which highlights the potential for the spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment. This study underscores the need for continued surveillance and monitoring of resistance genes in wastewater and the environment, especially for LTCFs which were not paid important attention to in the past several years. Future research should focus on further characterizing the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying the dissemination of mcr-1 in wastewater from LTCFs and the environment, as well as on the development of novel strategies to mitigate the spread of antibiotic resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We also thank Prof. Hongyu Ou from Shanghai Jiao Tong University for providing EC C600 isolate.

The work was supported by the Three-Year Initiative Plan for Strengthening Public Health System Construction in Shanghai (2023–2025) Principal Investigator Project (grant no. GWVI-11.2-XD28) and Key Discipline Project (grant no. GWVI-11.1-09).

Contributor Information

Zhengan Yuan, Email: zhenganyuan@scdc.sh.cn.

Min Chen, Email: chenmin@scdc.sh.cn.

Zhongxiong Lai, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Since our sampling did not hurt animals or pollute the environment, ethical approval was not required for this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Sequences were deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website under BioProject number PRJNA967846.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.03707-23.

Amino acid sequences of E. coli strains harboring the mcr-1 gene in this study.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Madec JY, Haenni M, Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2017. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase/AmpC- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in animals: a threat for humans? Clin Microbiol Infect 23:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang Q, Pogue JM, Li Z, Nation RL, Kaye KS, Li J. 2020. Agents of last resort: an update on polymyxin resistance. Infect Dis Clin North Am 34:723–750. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharma J, Sharma D, Singh A, Sunita K. 2022. Colistin resistance and management of drug resistant infections. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022:4315030. doi: 10.1155/2022/4315030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu LF, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu JH, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shen Y, Zhou H, Xu J, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Walsh TR, Shao B, Wu C, Hu Y, Yang L, Shen Z, Wu Z, Sun Q, Ou Y, Wang Y, Wang S, Wu Y, Cai C, Li J, Shen J, Zhang R, Wang Y. 2018. Anthropogenic and environmental factors associated with high incidence of mcr-1 carriage in humans across China. Nat Microbiol 3:1054–1062. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0205-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang R, van Dorp L, Shaw LP, Bradley P, Wang Q, Wang X, Jin L, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Rieux A, Dorai-Schneiders T, Weinert LA, Iqbal Z, Didelot X, Wang H, Balloux F. 2018. The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Nat Commun 9:1179. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03205-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hussein NH, Al-Kadmy IMS, Taha BM, Hussein JD. 2021. Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: a comprehensive review. Mol Biol Rep 48:2897–2907. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06307-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rhouma M, Madec JY, Laxminarayan R. 2023. Colistin: from the shadows to a one health approach for addressing antimicrobial resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents 61:106713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2023.106713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y, Xu C, Zhang R, Chen Y, Shen Y, Hu F, Liu D, Lu J, Guo Y, Xia X, et al. 2020. Changes in colistin resistance and mcr-1 abundance in Escherichia coli of animal and human origins following the ban of colistin-positive additives in China: an epidemiological comparative study. Lancet Infect Dis 20:1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30149-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Büchler AC, Gehringer C, Widmer AF, Egli A, Tschudin-Sutter S. 2018. Risk factors for colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a low-endemicity setting for carbapenem resistance - a matched case-control study. Euro Surveill 23:1700777. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.30.1700777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang PH, Cheng YH, Chen WY, Juan CH, Chou SH, Wang JT, Chuang C, Wang FD, Lin YT. 2021. Risk factors and mechanisms of in vivo emergence of colistin resistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Antimicrob Agents 57:106342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feng J, Xu Z, Zhuang Y, Liu M, Luo J, Wu Y, Chen Y, Chen M. 2023. The prevalence, diagnosis, and dissemination of mcr-1 in colistin resistance: progress and challenge. Decoding Infection and Transmission 1:100007. doi: 10.1016/j.dcit.2023.100007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutinel M, Larsson DGJ, Flach CF. 2022. Antibiotic resistance genes of emerging concern in municipal and hospital wastewater from a major Swedish city. Sci Total Environ 812:151433. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu L, Shuai XY, Lin ZJ, Sun YJ, Zhou ZC, Meng LX, Zhu YG, Chen H. 2022. Landscape of genes in hospital wastewater breaking through the defense line of last-resort antibiotics. Water Res 209:117907. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Fallon E, Kandel R, Schreiber R, D’Agata EMC. 2010. Acquisition of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: incidence and risk factors within a long-term care population. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31:1148–1153. doi: 10.1086/656590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mao YC, Chang CL, Huang YC, Su LH, Lee CT. 2018. Laboratory investigation of a suspected outbreak caused by Providencia stuartii with intermediate resistance to imipenem at a long-term care facility. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 51:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee CM, Lai CC, Chiang HT, Lu MC, Wang LF, Tsai TL, Kang MY, Jan YN, Lo YT, Ko WC, Tseng SH, Hsueh PR. 2017. Presence of multidrug-resistant organisms in the residents and environments of long-term care facilities in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 50:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Dulm E, Tholen ATR, Pettersson A, van Rooijen MS, Willemsen I, Molenaar P, Damen M, Gruteke P, Oostvogel P, Kuijper EJ, Hertogh CMPM, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, Scholing M. 2019. High prevalence of multidrug resistant Enterobacteriaceae among residents of long term care facilities in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. PLoS One 14:e0222200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Löffler P, Escher BI, Baduel C, Virta MP, Lai FY. 2023. Antimicrobial transformation products in the aquatic environment: global occurrence, ecotoxicological risks, and potential of antibiotic resistance. Environ Sci Technol 57:9474–9494. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c09854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hassoun-Kheir N, Stabholz Y, Kreft J-U, de la Cruz R, Romalde JL, Nesme J, Sørensen SJ, Smets BF, Graham D, Paul M. 2020. Comparison of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes abundance in hospital and community wastewater: a systematic review. Sci Total Environ 743:140804. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayashi W, Tanaka H, Taniguchi Y, Iimura M, Soga E, Kubo R, Matsuo N, Kawamura K, Arakawa Y, Nagano Y, Nagano N. 2019. Acquisition of mcr-1 and cocarriage of virulence genes in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from municipal wastewater influents in Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e01661-19. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01661-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hassen B, Abbassi MS, Ruiz-Ripa L, Mama OM, Ibrahim C, Benlabidi S, Hassen A, Torres C, Hammami S. 2021. Genetic characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from a biological industrial wastewater treatment plant in Tunisia with detection of the colistin-resistance mcr-1 gene. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 97:fiaa231. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang X, Li L, Sun F, Wang J, Chang W, Chen F, Peng J. 2021. Detection of mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli in slaughterhouse wastewater collected from Dawen river. Vet Med Sci 7:1587–1592. doi: 10.1002/vms3.489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiang B, Du P, Jia P, Liu E, Kudinha T, Zhang H, Li D, Xu Y, Xie L, Yang Q. 2020. Antimicrobial susceptibility and virulence of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in China, a multicenter longitudinal epidemiological study. Front Microbiol 11:1611. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feng J, Zhuang Y, Luo J, Xiao Q, Wu Y, Chen Y, Chen M, Zhang X. 2023. Prevalence of colistin-resistant mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli isolated from children patients with diarrhoea in Shanghai, 2016-2021. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 34:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2023.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rebelo AR, Bortolaia V, Kjeldgaard JS, Pedersen SK, Leekitcharoenphon P, Hansen IM, Guerra B, Malorny B, Borowiak M, Hammerl JA, Battisti A, Franco A, Alba P, Perrin-Guyomard A, Granier SA, De Frutos Escobar C, Malhotra-Kumar S, Villa L, Carattoli A, Hendriksen RS. 2018. Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance determinants, mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 for surveillance purposes. Euro Surveill 23:17-00672. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.6.17-00672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borowiak M, Baumann B, Fischer J, Thomas K, Deneke C, Hammerl JA, Szabo I, Malorny B. 2020. Development of a novel mcr-6 to mcr-9 multiplex PCR and assessment of mcr-1 to mcr-9 occurrence in colistin-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates from environment, feed, animals and food (2011-2018) in Germany. Front Microbiol 11:80. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang P, Xiong Y, Lan R, Ye C, Wang H, Ren J, Jing H, Wang Y, Zhou Z, Cui Z, Zhao H, Chen Y, Jin D, Bai X, Zhao A, Wang Y, Zhang S, Sun H, Li J, Wang T, Wang L, Xu J. 2011. pO157_Sal, a novel conjugative plasmid detected in outbreak isolates of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Clin Microbiol 49:1594–1597. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02530-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schürch AC, Arredondo-Alonso S, Willems RJL, Goering RV. 2018. Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene-based approaches. Clin Microbiol Infect 24:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Giufrè M, Monaco M, Accogli M, Pantosti A, Cerquetti M, PAMURSA Study Group . 2016. Emergence of the colistin resistance mcr-1 determinant in commensal Escherichia coli from residents of long-term-care facilities in Italy. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:2329–2331. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng J, Wu H, Zhuang Y, Luo J, Chen Y, Wu Y, Fei J, Shen Q, Yuan Z, Chen M. 2023. Stability and genetic insights of the co-existence of blaCTX-M-65, blaOXA-1, and mcr-1.1 harboring conjugative IncI2 plasmid isolated from a clinical extensively-drug resistant Escherichia coli ST744 in Shanghai. Front Public Health 11:1216704. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1216704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xie J, Liang B, Xu X, Yang L, Li H, Li P, Qiu S, Song H. 2022. Identification of mcr-1-positive multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from clinical samples in Shanghai, China. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 29:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2022.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin H, Chen W, Zhou R, Yang J, Wu Y, Zheng J, Fei S, Wu G, Sun Z, Li J, Chen X. 2022. Characteristics of the plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene mcr-1 in Escherichia coli isolated from a veterinary hospital in Shanghai. Front Microbiol 13:1002827. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1002827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang D, Zou H, Zhao L, Li Q, Meng M, Li X, Berglund B. 2023. High prevalence of Escherichia coli co-harboring conjugative plasmids with colistin- and carbapenem resistance genes in a wastewater treatment plant in China. Int J Hyg Environ Health 250:114159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2023.114159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luo Q, Wu Y, Bao D, Xu L, Chen H, Yue M, Draz MS, Kong Y, Ruan Z. 2023. Genomic epidemiology of mcr carrying multidrug-resistant ST34 Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in a one health context: the evolution of a global menace. Sci Total Environ 896:165203. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zając M, Sztromwasser P, Bortolaia V, Leekitcharoenphon P, Cavaco LM, Ziȩtek-Barszcz A, Hendriksen RS, Wasyl D. 2019. Occurrence and characterization of mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli isolated from food-producing animals in Poland, 2011-2016. Front Microbiol 10:1753. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boueroy P, Wongsurawat T, Jenjaroenpun P, Chopjitt P, Hatrongjit R, Jittapalapong S, Kerdsin A. 2022. Plasmidome in mcr-1 harboring carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales isolates from human in Thailand. Sci Rep 12:19051. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21836-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kang M, Yang J, Kim S, Park J, Kim M, Park W. 2022. Occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes and multidrug-resistant bacteria during wastewater treatment processes. Sci Total Environ 811:152331. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stachurová T, Sýkorová N, Semerád J, Malachová K. 2022. Resistant genes and multidrug-resistant bacteria in wastewater: a study of their transfer to the water reservoir in the Czech Republic. Life (Basel) 12:147. doi: 10.3390/life12020147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zainab SM, Junaid M, Xu N, Malik RN. 2020. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) in groundwater: a global review on dissemination, sources, interactions, environmental and human health risks. Water Res 187:116455. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Amino acid sequences of E. coli strains harboring the mcr-1 gene in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences were deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website under BioProject number PRJNA967846.