Abstract

The brain represents an organ with a particularly high diversity of genes that undergo post-transcriptional gene regulation through multiple mechanisms that affect RNA metabolism and, consequently, brain function. This vast regulatory process in the brain allows for a tight spatiotemporal control over protein expression, a necessary factor due to the unique morphologies of neurons. The numerous mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation or translational control of gene expression in the brain include alternative splicing, RNA editing, mRNA stability and transport. A large number of trans-elements such as RNA-binding proteins and micro RNAs bind to specific cis-elements on transcripts to dictate the fate of mRNAs including its stability, localization, activation and degradation. Several trans-elements are exemplary regulators of translation, employing multiple cofactors and regulatory machinery so as to influence mRNA fate. Networks of regulatory trans-elements exert control over key neuronal processes such as neurogenesis, synaptic transmission and plasticity. Perturbations in these networks may directly or indirectly cause neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. We will be reviewing multiple mechanisms of gene regulation by trans-elements occurring specifically in neurons.

Keywords: RNA editing and neuronal granules, alternative splicing

INTRODUCTION

Post-transcriptional regulation (PTR) of mRNA is thought to be essential at every step of its complex life cycle as it travels from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. In neurons, the influences of trans-elements, such as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and non-coding RNAs, provide an essential means through which most complex molecular pathways are regulated post-transcriptionally. Trans-elements function via their ability to recognize specific cis-elements such as sequences or structures present on both precursor and mature mRNAs. They serve as important gatekeepers of gene expression in multiple processes such as splicing, translation, RNA transport, RNA stability and decay that ultimately dictate several aspects of neuronal functioning, including cognition.

Neurons are known for their extraordinary anatomical and functional diversity. While this remarkable phenomenon has long been recognized, little is known about how this diversity arises. It is achieved, in part, through highly complex translational control that dictates RNA metabolism. For instance, pre-mRNA processing events such as alternative splicing (AS) and RNA editing contribute greatly to the proteome diversity and functional complexity of the nervous system.

There are many indicators that allude to the role of trans-element facilitated PTR in establishing neuronal diversity. These include long genes coding for signaling molecules, receptors, ion channels and cell adhesion molecules that are essential for neuronal communication and connectivity. The disrupted forms of these genes are implicated in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and Rett syndrome [82, 201, 230]. Long neuronal effector genes have been suggested to contribute disproportionately to neuronal transcriptional diversity [200, 253]. This hypothesis is bolstered by studies where long genes were shown to be expressed at higher levels in neurons when compared to non-neuronal cells in the nervous system [82, 201]. Moreover, long genes tend to have larger numbers of exons and therefore are ideal targets for post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms such as AS, which results in the expression of large numbers of distinct isoforms. Additionally, the untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNA are a hotbed of cis-elements for RBPs and non-coding RNA (ncRNA), particularly the 3′-UTR. Brain tissues were observed to express higher levels of mRNA isoforms with long 3′-UTR as opposed to short 3′-UTRs [42, 173, 248]. Of the several cell types in the brain, longer 3′-UTR isoforms were particularly enriched in neurons as opposed to astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocytes [226, 239, 244].

Thus, it is essential to understand how regulatory factors function whether it be individually or in conjunction with other factors. This review attempts to condense their roles their mechanism of action through which they achieve translational control during several processes. While these means of regulation are also rampant in non-neuronal cells, we have focused on neurons for the sake of brevity. We have also chosen to place emphasis on specific examples that are typical of regulation by trans-elements that involve one-on-one interactions with their target mRNAs leading to changes in gene expression and synaptic plasticity. This article will focus on reviewing multiple processes of gene regulation occurring in neurons and will highlight some of the underlying mechanisms that allow for neuronal gene expression and function (illustrated in Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Illustration depicting key post-transcriptional events and trans-elements involved in involved in PTR in neurons.

AS AND NEURONAL DIVERSITY

AS is essential for RNA processing during several critical stages of neuronal development and function—memory consolidation, plasticity, cell signaling neuronal differentiation, axon guidance and synapse formation (reviewed in [80, 131, 132]). AS has the capacity to generate hundreds to several thousands of splice variants in the nervous systems of animals [213]. AS can affect downstream regulatory processes such as nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) and add additional layers of post-transcriptional gene regulation ([124] and reviewed in [99, 119]). Most of these splicing events cause inclusion or exclusion of conserved protein domains. They may also introduce a frame shift or a premature stop codon, which triggers NMD. The series of events that lead to NMD could potentially regulate transcript stability, diversity and abundance in the transcriptome of different neuronal cell populations ([212, 242] and reviewed in [4]). Regulated splicing is seemingly coupled to NMD that ultimately determines protein abundance via the regulation of the transcriptome, i.e. isoform diversity and transcript abundance ([124, 242] and reviewed in [143]).

AS of pre-mRNAs produces functionally distinct isoforms that are essential for neuronal development, plasticity, complex behaviors and cognition (reviewed in [132]). AS is a common mechanism to diversify genetic output in metazoans and is especially prevalent in the mammalian nervous system (reviewed in [24, 142]). Neuronal splicing events expand the mammalian neuronal transcriptome and are regulated by several trans-factors such as RBPs and microRNAs (miRNAs). Aberrant splicing has been implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders and splicing-correcting therapies have been successfully used to improve disease symptoms [77, 84, 97, 195]. Thus, understanding the underlying mechanisms of AS regulation by trans-elements is critical for discovering new therapeutic interventions.

Trans-factors that regulate splicing have been demonstrated to be expressed in a tissue-specific manner to influence AS forms of particular transcripts. They control the choice of splicing within a transcript by binding to the pre-mRNA and enhancing or silencing specific splicing events [24, 142]. The trans-factors discussed in this review are enlisted in Table 1. AS alters exon composition by generating numerous exon combinations in mRNA isoforms, which are then translated into the final proteins. Coordinated spatiotemporal AS regulation by RBPs is an important contributor to neuronal diversity. RBP families including PTB, RBFOX, NOVA, serine/arginine-rich, STAR and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) that bind to RNA motifs to regulate AS. RBPs determine alternative exon usage by recognizing cis-regulatory elements on pre-mRNAs ([223] and reviewed in [80]).

Table 1.

List of trans-factors discussed in this review

| Trans-factor/s | Category of trans-factor | mRNA target | Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB | RBP | mef2 | AS | Maintaining survival and neuronal function in N2A cells [92, 252] |

| miR-124 | miRNA | ptb | mRNA degradation | Degradation of PTB in neurons upregulates nPTB expression, which is crucial for nervous system development [136] |

| SLM2 | RBP | nrxn1,2 and 3 | AS | Specification of glutamatergic synapse [213] |

| RBFOX | RBP | ankG | AS | Formation of axon initiation segment [104] |

| trkb | Translational control | Promotes BDNF dependent long-term memory [210] | ||

| vamp | Translational upregulation | Aids Inhibitory synaptic transmission during learning and memory [222] | ||

| FBF-1 | RBP | egl-4 | Translational upregulation and localization | Adaptation to odors, i.e. olfactory memory [108] |

| ADR-2 | RBP | clec-41 | RNA editing leading to stability and translational upregulation | Regulates chemotaxis in C. elegans [50] |

| TDP-43 | RBP | cdkn1a | Translational upregulation | Induces cell cycle block leading to cell death [221] |

| HUD | RBP | nrn1 | Localization of Nrn1 mRNA in axons | Promotes synapse formation [147] |

| gap-43 | Axonal localization | Assist axon growth and regeneration [150] | ||

| Translin | RBP | bdnf | Dendritic localization | LTP and synaptic plasticity [165] |

| FMRP miR-125b | RBP miRNA | nr2a | Maintains NMDA receptor ratio by marking mRNA for degradation | Promotes synaptic plasticity [64] |

| BACE1-AS | lncRNA | bace1 | Stability and translational upregulation | Aberrant cleavage of APP leading to Alzheimer’s disease [69] |

| miR-485-5p | miRNA | bace1 | MRNA degradation | Prevents APP aggregation by degrading the BACE1 enzyme that aberrantly cleaves APP [69] |

AS is highly context-dependent and neuron-specific

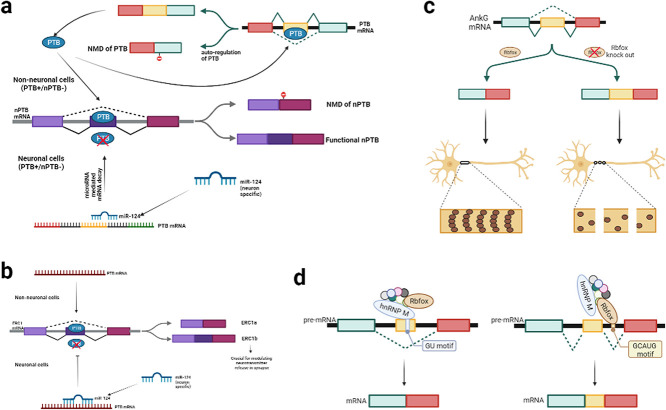

AS can be highly context-dependent and neuron-specific (reviewed in [80]). During neural development, some AS events are reprogrammed by trans-factors causing switching in protein expression. RBPs are known to bind pre-mRNA and control AS by binding sequence-specific sites. AS may be controlled by multiple RBPs depending on the cell identity. Different trans-factors bind to the same RNA target sequence but may create distinct splicing outcomes in different tissues or developmental stages [223]. An apt example of this is PTB and neural PTB (nPTB) RBPs that are discussed below and illustrated in Fig. 2a and b.

Figure 2.

(a) Neuron specific splicing patterns of PTB and nPTB. In non-neuronal cells, PTB mRNA undergoes normal translation forming functional PTB that in turn binds to nPTB mRNA leading to exon skipping and NMD. Also, PTB binds to its own mRNA in a concentration dependent manner, resulting in NMD, thus ensuring homeostasis. However, in neuronal cells, miR-124 is expressed that binds to the PTB mRNA leading to translational suppression. Lower concentration of PTB restricts its binding to nPTB mRNA (adapted from [43, 96]). (b) Similar to nPTB, PTB mediates the AS pattern of ERC mRNA. Presence of PTB in non-neuronal cells leads to exon exclusion in ERC mRNA leading to synthesis of ERC1a isoform, whereas in non-neuronal cells, ERC1b isoform is expressed, which contains an additional exon (adapted from [26]). (c) RbFox determines the splicing pattern of AnkG mRNA. Knockout of RbFox leads to exon inclusion in AnkG resulting in a mutant protein that impairs assembly of the AIS (adapted from [104]). (d) RbFox with hnRNP M and other regulators forms the large macromolecular assembly of splicing regulator complex that acts constitutively based on the presence of corresponding binding sites and is involved in changes in splicing patterns (adapted from [46]).

Polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins, PTB and nPTB are structurally similar paralogs across all four of their RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and well-known AS regulators [139, 164]. They bind to CU-rich regulatory regions near PTB-repressed exons and alter the assembly of the spliceosomes at adjacent splice sites [2, 128, 164, 194]. While PTB is expressed in neuronal precursor cells, glia and other non-neuronal cells, nPTB expression is restricted to post-mitotic neurons and is actively repressed in non-neuronal cells in part due to PTB-induced AS of nPTB mRNA, leading to NMD. This mutually exclusive pattern of expression of PTB and nPTB in the brain during neuronal differentiation is established post-transcriptionally and controls numerous splicing programs (reviewed in [198, 224]).

Post-transcriptional reprogramming of AS

The switch in RBP alters the splicing of many alternative exons that may be included or excluded in neuronal mRNA. PTB and nPTB target genes are essential for the remodeling of neurons during axon outgrowth and synaptogenesis ([26, 45, 251] and reviewed in [51, 93]). nPTB also interacts with the neuron-specific splicing regulator and RBP, NOVA1 [176]. PTB, and not nPTB, strongly represses the alternative β exon of transcription factor MEF2 (MEF2 plays a key role in neuronal function and survival) in N2A cells during P19 differentiation into neurons ([138, 252] and reviewed in [92, 192]). Rab6IP2 protein (also called ERC1), which is expressed in two spliced isoforms, is involved in membrane trafficking. ERC1a is ubiquitously expressed, but ERC1b is neuron-specific due to inclusion of an exon and modulates neurotransmitter release at the synapse. ERC1b neuron-specific exon is repressed by PTB in non-neuronal cells. Loss of PTB function leads to the synthesis of synaptic ERC1b due to AS, implicating this event in the synthesis of components required for efficient presynaptic function during neuronal differentiation [227]. This is illustrated in Fig. 2b.

The K homology (KH)-domain of RBP, SLM2, is essential for the correct specification of glutamatergic synapses in the mouse hippocampus. SLM2 modifies the AS of endogenous neurexin in the hippocampus. Genome-wide mapping has revealed highly selective SLM2-dependent AS events consisting of very few mRNAs that encode synaptic proteins including the neurexins (Nrxn1, 2 and 3). Neurexins are presynaptic transmembrane cell-adhesion molecules that play a significant role in synapse regulation. The neurexin mRNA has six splice sites, of which splice site 4 is extensively studied. The inclusion or exclusion of this splice site determines the ligand to which neurexin binds. SLM-2 mediates the AS of neurexin-1 at splice site 4 [44].

Genetic change to a single SLM2-dependent target exon in Neurexin-1 rescued synaptic function, plasticity and behavioral defects in Slm2 knockout mice. SLM2 is selectively expressed in specific neuronal cell types and regulates very few alternative exons that ultimately dictate synaptic properties in neuronal circuits [213].

Rbfox family of RBPs and AS

Rbfox family of RBPs consists of three highly conserved splicing factors, Rbfox1 (A2bp1), Rbfox2 (Rbm9) and Rbfox3 (NeuN), that contribute to neuronal development and maturation ([104] and reviewed in [114]). Studies in mouse models have demonstrated the tissue specificity of these Rbfox splicing factors, i.e. RBFOX1 is specific to the brain, the heart and the muscle, whereas RBFOX2 is expressed in multiple organs like the ovary, the brain, the kidney, the heart, the lung epithelium, the muscle and the embryo. Comparatively, RBFOX3 is not well characterized and generally found in neurons [33].

RBFOX1 regulates a wide array of AS networks during neuronal development. Defects in RBFOX1 have been implicated in many neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders including ASD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy (reviewed in [23]). RNA sequencing performed to study RBFOX1 splicing network in primary human neural stem cells during differentiation implicates it in the AS events of genes involved in key developmental processes such as cellular proliferation, cytoskeletal organization, cell adhesion and signaling. Thus, RBFOX1 may behave as a molecular switch that promotes correct differentiation of neuronal progenitors into different functional cell types [78]. The role of RBFOX in splicing is illustrated in Fig. 2c and d.

Rbfox proteins regulate AS by binding to conserved (U)GCAUG elements in the transcript [107, 127, 177]. While strong binding to canonical Rbfox motifs is evident, several additional motif variants or secondary motifs were also detected in abundance in previous studies. Rbfox proteins bind to the secondary motifs in vivo and their regulatory function with respect to these motifs is dependent on Rbfox concentration, which is especially high during neuronal development. The Rbfox concentration-dependent regulation of splicing events adds an additional layer of control during neuronal differentiation and cell type specification [20]. Although Rbfox proteins recognize highly conserved binding sites on target mRNA, they do not function in isolation. Their structures and diverse roles suggest that they interact with various protein partners to achieve several outcomes. Nuclear Rbfox proteins are part of a large macromolecular assembly of splicing regulators (illustrated in Fig. 2d). Rbfox are bound within this multimeric complex that also contains non-RRM domain proteins such as hnRNPs like hnRNP M, hnRNP H, hnRNP C, nuclear matrix protein (Matrin3), double-stranded RBP (NF110/NFAR-2), RBP with domain associated with zinc fingers (NF45) and DEAD-box helicase (DDX5). This defined set of splicing cofactors affects Rbfox by enhancing its target recruitment considerably, thereby demonstrating additional complexities of splicing networks [46].

Loss of function alleles of Rbfox1 and Rbfox2 makes mice more susceptible to seizures and causes cerebellar defects and ataxia [85, 86]. Mutations in Rbfox genes are also associated with autism, schizophrenia and epilepsy [14, 21, 140, 190, 240]. Rbfox triple knockout ventral spinal neurons have defects in AS of cytoskeletal, membrane and synaptic proteins and go on to display aberrant electrophysiological activity [104].

Rbfox depletion causes the defective assembly of the axon initial segment (AIS) that is a subcellular structure important for action potential initiation and consequently regulates neuronal excitability and plasticity (reviewed in [181]). Maturation of AIS relies on the recruitment and accumulation of AnkG in the proximal axon that is responsible for assembling essential binding partners [91]. AIS defects observed in Rbfox triple knockout neurons are caused by defective splicing of AnkG that is unable to integrate into the actin cytoskeletal lattice. Exon 34 of AnkG codes for a short peptide that inhibit AnkG-βIV spectrin interaction, where βIV spectrin plays a critical role in linking ankG/Na+ channel to actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in [101]). AnkG function requires exclusion of an alternative exon mediated by Rbfox, which in turn leads to the proper establishment of AIS and, subsequently, neuronal maturation [104]. This is illustrated in Fig. 2c.

Coordination of RBPS and miRNAS during AS events

RBPs are also known to work in conjunction with the action of miRNAs to control AS. In the case of PTB, previously mapped binding sites are situated close to predicted miRNA target sites [241]. This bolsters the possibility of RNA stability regulation by PTB via functional interplay with miRNAs.

Multiple neuron-specific miRNA, such as miR-9/9* and miR-124, play important roles in neuronal differentiation [245]. miR-9 post-transcriptionally inactivates the PTB paralog nPTB by targeting its binding site in the 3′-UTR to regulate neuronal maturation in human cells. miR-124 is a regulator of the transcription silencing REST complex, which represses numerous neuron-specific genes in non-neuronal cells including miR-124 itself [11, 37]. miR-124 also modulates the programmed switch of PTB to nPTB during neuronal differentiation by downregulating PTB expression, which in turn reprograms neuronal-specific AS events ([136] and illustrated in Fig. 2a).

There are also several lines of evidence that PTB dependent downregulation of multiple components of the REST complex occurs in the brain to maintain non-neural cell identity. Multiple PTB binding peaks were observed in the 3′-UTR of key REST complex factors, CoREST and HDAC1, both of which have been implicated in neurogenesis [241]. In the case of REST complex factor SCP1, mutational analysis of binding sites of PTB and miR-124 demonstrated that PTB directly competes with miR-124 on its target site in the 3′-UTR of the SCP1 gene. miR-124, REST and PTB form an intricate regulatory loop that induces significant AS reprogramming affecting the fate of neuronal lineage [59, 95].

In other instances, PTB has been observed to enhance miRNA targeting by inducing structural changes to the mRNA. GNPDA1 is upregulated by PTB via its 3′-UTR. PTB binding sites in the 3′-UTR of GNPDA1 transcripts are immediately downstream of potential targeting sites for several miRNA, including Let-7b, miR-181b and miR-196a. Luciferase reporter assays have demonstrated enhanced GNPDA1 expression in a PTB-dependent manner. The mechanism for PTB-dependent enhancement of miRNA action relies on a stem-loop; this demonstrates a dynamic switch between the single-stranded and double-stranded states. The presence of PTB enhances the single-strandedness of the stem-loop, exposing the region that houses miRNA target sites. PTB can potentially modulate RNA secondary structure that may expose or shield miRNA target sites in the region [241].

RNA EDITING

RNA editing is widespread in mRNAs of higher eukaryotes and more specifically, editing by Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) RBPs has been found to be most abundant in the nervous system [6, 123]. RNA editing has profound effects on the transcriptome and concordantly the proteome, demonstrating another mechanism through which biological complexity is achieved (reviewed in [65, 161]). Mammals contain three types of ADARs, ADAR1 (primary editor of repetitive sites), ADAR2 (primary editor of non-repetitive coding sites) and the catalytically inactive ADAR3, which predominantly acts as an inhibitor of editing. ADARs catalyze the deamination of adenosine (A) into inosine (I) (known as A-to-I editing) in double-stranded RNA post-transcriptionally and this form of mRNA editing is highly prevalent (reviewed in [16]). Inosine is read as guanosine by the cellular machinery, thereby changing the identity of the encoded protein by altering a codon or mRNA regulatory site (reviewed in [160]).

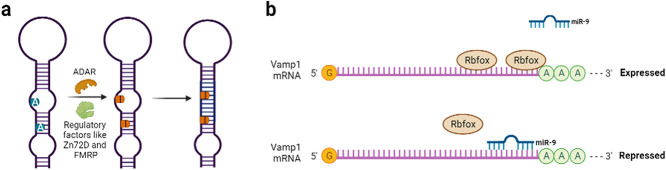

A-to-I editing is known to alter the critical properties of neuronal proteins and is consequently important for synaptic transmission (reviewed in [206]). The catalytically inactive ADAR3 represses RNA editing by competitively binding to target mRNAs in both human cells and Caenorhabditis elegans [163, 179, 229]. ADAR2 in particular is responsible for editing several mammalian pre-mRNAs encoding ion channels involved in regulating neuronal excitability (reviewed in [184]). The dysregulation of ADAR2 is involved in many neurological diseases (reviewed in [196]). ADAR2 contains two functionally redundant nuclear localization signals, which elevate its nuclear localization and expression. ADAR2 subcellular localization has been demonstrated to be exclusively nuclear that may explain the crucial role of editing during neuronal development and maturation [53, 186]. ADAR mediated RNA editing is illustrated in Fig. 3a.

Figure 3.

(a) ADAR mediated RNA editing. ADAR mediates the conversion of A-to-I in mRNAs and factors like Zn72D and FMRP regulates this process (adapted from [17, 187, 218]). (b) Translational control of Vamp1 mRNA. Rbfox and miR-9 competitively approach the binding site in the 3′-UTR of Vamp1 mRNA. Binding of Rbfox enhances the mRNA stability and aids translation, whereas binding of miR-9 represses translation of Vamp1 (adapted from [222]).

The Drosophila melanogaster Adar, a human Adar2 homolog, regulates sleep by altering synaptic plasticity. Data indicates that Adar suppresses glutamatergic signaling to suppress sleep. Adar knockout specifically upregulates vesicular glutamate transporter and hyperactivates NMDA signaling leading to the sustained release of neurotransmitters. This probably could increase synaptic potentiation associated with sleep-promoting neurons and thus promote sleep in Adar mutants. Additionally, Adar mutants affect neuronal structure and physiology. The consequences of loss of Adar activity also include abnormal circadian motor patterns and male courtship behaviors [22, 106, 137, 183]. Caenorhabditis elegans contains a single ADAR enzyme, the neural ADR-2. A novel technique that combines neural cell isolation with RNA-sequencing and editing site detection with software for accurately identifying locations of RNA editing software has identified over 7300 editing sites, with 104 novel edited genes in the nervous system transcriptome of C. elegans. A differential expression analysis in neural cells following the loss of adr-2 has implicated the clec-41 gene in the regulation of proper chemotaxis. The clec-41 transcript was shown to be edited in the 3′-UTR region and neural transgenic expression of clec-41 in adr-2 deficient C. elegans was sufficient to rescue the aberrant chemotaxis, displaying a tissue-specific role of ADR-2 [50]. Such significance of RNA editing necessitates a better understanding of how these processes are regulated.

Regulation of RNA editing by RBPs

Global changes in RNA editing have been reported in disease and development, necessitating a better understanding of this means of regulation. While ADAR proteins are well-known regulators of the human editomes (reviewed in [161]). ADAR editing only accounts for some of the editing variations that differ across tissues and development [28, 204, 228]. Concordantly, several RBPs have been found to mediate RNA editing providing additional means for diversifying editing mechanisms via trans-regulation. RBPs such as RPS14 and SFRS9 modulate ADAR2 activity. They exhibit substrate-specific RNA binding that inhibits editing of the substrates. It may be possible that these factors are involved in direct competitive binding at or near the ADAR2 editing site. They also show direct interaction and colocalization with ADAR2 that could mean they form complexes with ADAR2 at specific editing sites [205].

The RBP zinc-finger protein at 72D (Zn72D) was identified as a broadly influential RNA editing regulator. Zn72D knockdown causes a decrease in ADAR protein levels in the D. melanogaster brain that leads to mRNA editing and splicing changes accompanied by defects at the neuromuscular junction and hence impaired locomotion in D. melanogaster [187, 237]. ADAR and Zn72D colocalize in the nuclei of brain tissue and co-immunoprecipitate together indicating that they physically interact with one another. Many edited transcripts also immunoprecipitated with D. melanogaster Zn72D. The ADAR and Zn72D interaction within the nucleus appears to be RNA-dependent, suggesting that they either bind the same RNAs or are part of the same ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. In the D. melanogaster brain, Zn72D appears to regulate both splicing and/or editing in different subsets of transcripts [187].

In addition to the findings in D. melanogaster, Zn72D mouse homolog, Zfr, has also been implicated in RNA editing in primary cortical neurons. Zn72D, the human homolog of Zfr has been reported to influence pre-mRNA splicing and RNA editing suggesting that this mode of editing regulation is highly conserved and elucidation of mechanistic details of these processes may contribute significantly to therapeutic interventions [79, 90, 187].

FMRP family of RBPS in RNA editing

The fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMRP) family of RBPs affects RNA editing in multiple organisms [22, 76, 179, 193]. Loss of FMRP protein function leads to heritable intellectual disability. While FMRP is a RBP typically associated with translational repression, D. melanogaster fragile X homolog (dFMR1) has also been implicated in RNA editing via dADAR. dFMR1 biochemically interacts with dADAR and this interaction seemingly affects the RNA editing of several dADAR targets. These targets happen to have key roles in the modulation of the synaptic architecture of neuromuscular junction and synaptic transmission suggesting that dFMR1 regulation of dADAR activity is essential for the aforementioned functions. dFMR1 and dADAR are both RBPs that may associate in a common complex on shared RNA targets, this is further bolstered by immunoprecipitation experiments that demonstrate association of dFMR1 and dADAR on common RNA substrates. These findings link FMRP to novel neuronal functions via the RNA editing pathway [22].

Hypoediting of RNA in ASD subjects is a common trend across different brain regions. FXR1 is an RBP involved in the regulation of memory and emotions [39, 52]. FXR1 also reduces RNA editing in the brain in a cell type-specific manner and contributes to hypoediting in autism brains [211]. Immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrates that FXR1P binds to the regions containing ADAR1 sites and mutation of predicted FXR1 binding motifs causes higher editing levels at most target sites. These results assign roles of direct inhibitory regulation of editing sites to FXR1P through its interaction with ADAR1 and the RNA. In contrast, FMRP displays editing enhancing roles, demonstrating concomitant modulation of RNA editing by these two RBPs at several editing sites. Mutation or loss of FMRP binding sites in target RNA causes significant reduction in RNA editing indicating that FMRP interacts with RNA and ADAR to mediate editing. A vast number of studies implicate the involvement of FMRP in the pathogenesis of ASD, necessitating the elucidation of its molecular mechanisms [48, 72, 87, 88, 102, 105, 168, 174, 211].

The RNA binding sites of FMRP and FXR1P are significantly enriched around editing sites of transcripts in the frontal cortex of ASD patients, suggesting their role as direct regulators of RNA editing in ASD. Furthermore, FMRP and FXR1P interact with one another suggesting a synergistic regulation of RNA editing [250]. Western blot analysis shows that FMRP expression is absent or reduced in Fragile X syndrome patient brain samples, while ADAR1 and ADAR2 expression levels remain similar. Several lines of evidence, such as these, indicate that the dysregulation of RNA editing in Fragile X syndrome and ASD occur through common means involving FMRP regulation of RNA editing. This establishes a correlation between hypoediting and FMR1 and FXR1 genes demonstrating a shared RNA editing patterns and molecular deficit between two closely related neurodevelopmental disorders, ASD and Fragile X syndrome [211].

REGULATION OF RNA STABILITY, DECAY AND TRANSLATION BY RBPS

Post-transcriptional gene expression in the nervous system is tightly controlled by trans- acting elements such as RBPs and non-coding RNAs. This regulation affects vital processes such as splicing, translation, RNA transport, RNA stability and decay. Interdependent networks of RBPs may regulate complex pathways involved in various aspects of neuronal development and functioning. Hence, elucidation of the dynamics within RBP networks may shed light on the regulation of key neuronal processes such as neurogenesis, synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity.

Rbfox1 regulates RNA metabolism of hundreds of genes in neurons [86, 117, 233]. Dysregulation of RBFOX1 has been linked to intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease (PD) pathologies that are shared with dysregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling (reviewed in [23, 38]). BDNF is secreted during long-term potentiation (LTP) induction and is essential for the signaling leading up to LTP, making it a potent mediator of synaptic plasticity (reviewed in [134, 167]). Concordantly, it has key roles in cognitive functions [12, 167]. Abnormal activity of BDNF receptor Ntrk2 (TrkB) also impairs LTP and reduces synapse numbers that hinder hippocampus-dependent memory formation and consolidation (reviewed in [149]). The Ntrk2 gene generates different TrkB isoforms including full-length tyrosine kinase receptor (TrkB.FL) and truncated receptors sans the kinase domain (TrkB.T1). Dysregulation of TrkB isoforms expression is associated with neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders [57, 61, 67, 75].

Rbfox1 specifically regulates TrkB.T1 receptor levels in neurons. Overexpression of Rbfox1 impairs BDNF-dependent LTP and this defect can be rescued by restoring TrkB.T1 levels. Rbfox1 upregulation causes an increase in hippocampal TrkB.T1 isoform expression and as a result, impairs BDNF-dependent LTP, suggesting that Ntrk2 or TrkB is an important Rbfox1 target [78, 86, 117, 216]. Rbfox1 was the first factor shown to regulate Ntrk2 expression at the mRNA level. It directly binds to Ntrk2 RNA and promotes TrkB.T1 RNA stability, rather than AS. This notion is supported by Rbfox1 overexpression studies that only lead to the up-regulation and stability of TrkB.T1 RNA and has no effect on TrkB.FL; this is further confirmed by RNA-seq analysis displaying changed expression of only TrkB.T1 in a Rbfox1 overexpression background in mouse hippocampus. Another important discovery was that despite the presence of six ‘GCATG’ Rbfox1 binding sites in the 3′-UTR, the influence of RbFox1’s expression on TrkB.T1 mRNA levels appears to be independent of its action on the 3′-UTR region. This suggests that TrkB.T1 mRNA isoform may be regulated by Rbfox1 through different processes [210].

RNA-seq analysis shows that gain or loss of function of Rbfox1 seem to regulate different genetic landscapes indicating that Rbfox1 has broad genetic targets. Upregulation of Rbfox1 leads to an increased expression of TrkB.T1 that impairs BDNF-induced LTP. Surprisingly, reduction in Rbfox1 level does not have an effect TrkB.T1 expression. Most studies have assessed the consequences of RBFOX1 downregulation; however, upregulation of RBFOX1 is also tied to specific pathologies. For instance, iPSCs derived neurons from of PD patients have elevated RBFOX1 levels [129]. Interestingly, neurons of PD patients also display increased TrkB.T1 expression, which may indicate impairment of similar regulatory mechanism on TrkB.T1 in PD patients [73]. These studies indicate that upregulation or downregulation of specific RBPs could have entirely different genetic outcomes.

Cytoplasmic Rbfox1 promotes mRNA stability and/or translation by binding to a conserved motif in the 3′-UTRs of target transcripts and is highly enriched in the brain [30, 117]. In the hippocampus, vSNARE protein Vamp1 is an important cytoplasmic Rbfox1 target. Vamp1 is expressed specifically in inhibitory neurons, and loss of Vamp1 and Rbfox1 causes decreased inhibitory synaptic transmission and excitatory/inhibitory imbalance. In Rbfox1 Nes-cKO mice, loss of binding by RBFOX1 to Vamp1 3′-UTR strongly downregulated Vamp1 expression. Cytoplasmic Rbfox1 induces Vamp1 expression in part by blocking microRNA-9. RBFOX1 binding to Vamp1 3′-UTR increased mRNA levels possibly by promoting mRNA stability and/or translation along with antagonizing miR-9 action. Rbfox1 and miR-9 regulatory networks may modulate the expression of Vamp1 in an opposing manner to control inhibitory synaptic transmission during learning and memory. Cytoplasmic Rbfox1 largely affects a different set of transcripts from those regulated by nuclear rbfox1 highlighting additional post-transcriptional regulatory programs performed by the Rbfox family of RBPs aside from AS [222]. The translational control of Vamp1 mRNA is illustrated in Fig. 3b.

Memory consolidation via external sensory cues

Different patterns of stimulation alter LTP, long-term depression or homeostatic synaptic scaling within synaptic connections between neuronal cells. These processes establish memory formation ability as a function of experience (reviewed in [202, 203]). As an example, C. elegans sensory neurons are responsible for changes in animal behavior and this requires spatiotemporal control of regulated neuronal protein synthesis, which is said to adjust the synaptic connection strength as a function of experience. Caenorhabditis elegans responds to over 60 different attractant volatile chemical compounds via its AWA and AWC olfactory sensory neurons that mediate attraction and chemotaxis toward the odor [13]. Sensitivity to an odor depends on prior exposure time, brief exposure causes short-term adaptation and prolonged/repeated exposure causes long-term adaptation where the animals will ignore the odor [13, 36, 115].

Short- and long-term adaptation in C. elegans is facilitated by AWC sensory neurons that require the cGMP-dependent protein kinase EGL-4 and translational control of egl-4 mRNA by pumilio/Fem-3 binding factor (PUF) family of regulatory RBPs, essential for suitable behavioral response [115]. PUF proteins are typically categorized as translational repressors with few instances of promoting translational activation. For instance, D. melanogaster Pumilio mediated translational repression affects neuronal membrane excitability, synaptic development, dendritic branching and plasticity [145, 146, 243]. Drosophila melanogaster pumilio is also required for olfactory associative learning [60].

The 3′-UTR of egl-4 mRNA contains a highly conserved nanos response element that binds to the FBF-1 PUF protein. This specific binding event promotes adaptation to the odors, butanone and isoamyl alcohol and causes an increase in EGL-4 expression. FBF-1 directly activates translation of its target via its conserved 3′-UTR binding site in response to stimulation in adult functioning sensory neurons. The 3′-UTR of egl-4 also contains miRNA seed sequence 3′ of nanos response element, which enhances basal EGL-4 expression. In addition to the possible role of miRNAs in positively affecting EGL-4 translation in collaboration with FBF-1, FBF-1 may also help localize EGL-4 translation near the AWC sensory cilia [83]. Nervous system-wide presynaptic transcriptome of C. elegans has previously revealed that mRNAs for pumilio RBPs are abundant in synaptic regions. Presynaptic PUMILIOs have also been found to regulate associative memory [5]. Caenorhabditis elegans have 11 PUF proteins that interact with PUF protein partners such as NOS-1 and cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD-3, which may promote adaptation to other AWC-sensed odors via different targets [63, 225, 234].

Humans have two pumilio proteins, PUM1 and PUM2 [197]. These two proteins regulate a highly overlapping but non-identical set of mRNA targets. Mammalian pumilio proteins have been implicated in proper neuronal activity, ERK signaling, germ cell development and stress response, making them important factors in regulating neuronal functions [83, 118, 152, 209, 219].

Role of long non-coding RNAs in regulating neuronal transcripts and memory

Recent advances in RNA seq analysis have demonstrated beyond doubt that the neuronal transcript pool is enriched with non-coding RNAs (reviewed in [185]). ncRNAs could be clustered into two groups based on their length. Small non-coding RNAs are less than 200 bases long and comprises of miRNA, nucleolar RNA and Piwi RNA. On the other hand, a significant proportion of ncRNA is longer than 200 bases and comprises long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and circular RNA (reviewed in [125]).

The lncRNA is usually processed by RNA polymerase 2 and contains 5′ capping and 3′ poly A tailing similar to that of coding transcripts (reviewed in [125, 199]). Most lncRNAs are localized in the nucleus and play a significant role is chromatin remodeling ([148] and reviewed in [89]). However, some lncRNAs are cytoplasmic and play a crucial role in transcriptional control (reviewed in [247]). One of the most well-studied lncRNA involved in PTR is BACE1-AS. AS refers to anti-sense, i.e. BACE1-AS is transcribed from the anti-sense strand of the gene encoding BACE1. BACE1 codes for an enzyme, beta secretase, which catalyzes the aberrant cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP), leading to APP aggregation, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Typically, lower levels of BACE1 are preferred and maintained and this regulation is achieved through a miRNA, miR-485-5p, which induces translational repression of the BACE1 transcript. In contrast, the lncRNA BACE1-AS competes for the same sites as miR-485-5p and successful binding of BACE1-AS to BASE-1 mRNA enhances stability and promotes translation [69]. Higher levels of BACE1 increase the concentration of aberrantly cleaved APP that undergoes aggregation and affects neuronal signal transduction. Under normal conditions the concentrations of BACE1-AS and miR-485-5p are fine-tuned, whereas under stress or Alzheimer’s disease, BACE1-AS is overexpressed and as a result the translational levels of BASE1 are upregulated [68]. This function of BASE1-AS is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Role of BACE1-AS lncRNA in driving APP aggregation. BACE1 is an enzyme that cleaves APP aberrantly and drives aggregation. Under normal conditions, BACE1 expression is lower due to miRNA (miR-485-5p) mediated degradation of bace1 mRNA. However, during stress the expression of BACE1-AS is upregulated. BACE1-AS competes for the same site as miR-485-5p and successful binding of the lncRNA confers stability to bace1 mRNA and promotes translation. This image is based on work presented in [68, 69].

LOCALIZATION AND TRANSPORT OF RNA

Pioneering work published in 1988 firmly established the polarity of neurons. Their highly polarized nature is typically exhibited via a single axon and several dendrites that can extend structurally and functionally distinct processes far from the cell body (soma). The dendrites receive signals at the synapse and relay it to the soma that in turn propagates it along the axon to intended presynaptic sites. Thus, the polarized morphology of neurons is important for the directional flow of information in the nervous system [58].

Neurons rely on protein synthesis as they are essential sensors and effectors to communicate with different cell types. These proteins establish synaptic connections, changes in plasticity, memory and information storage. Neurons can extend hundreds of centimeters in length and respond to stimuli in remote regions within milliseconds. This is possible due to the rapid proteome modifications in axons and dendrites. These almost instantaneous metabolic changes rely on several mechanisms that facilitate local protein synthesis. These mechanisms dictate messenger RNA transport from the soma to distal ends of the neuron. Translationally silent mRNAs are targeted to synapses and subsequently lead to local synthesis of proteins. RNA transport is essential for local protein synthesis in neurons that allow for access to necessary proteins at distant sites (reviewed in [74]).

The elaborate architecture of neurons requires specialized machinery that is constantly regulated for localization and transport. Despite the significance of mRNA movement in neurons, we do not yet fully understand how these events are regulated. While we do not have a well-established model, various regulatory motifs in the mRNA and a plethora of trans-elements that bind to them work together to achieve localization. Anomalous RNA transport can lead to dire consequences with respect to several neurodegenerative diseases. The aftermath of transcription sees RNAs subjected to several modifications that make them attractive targets for trans-elements ([70, 133] and reviewed in [74]).

Additionally, the UTRs of mRNAs can potentially alter their targeting, stability and translational modulation. In microdissected rat brain slices, 3′-UTRs of transcripts localized at the axons, dendrites and synapses are significantly longer with longer half-lives than somata-enriched transcripts. Long 3′-UTRs are a hotbed of cis-elements that interact with trans-regulatory factors [215]. While the average length of the 5′-UTR of mRNAs is significantly shorter than the 3′-UTR in humans, mutations in 5′-UTR are known to impair localization. The 5′-UTRs also harbor RBP binding sites and other regulatory elements including IRES, uAUGs and uORFs that dictate translational efficiency [121, 147].

In previously published data on genes expressed in synaptic regions, relative to somatic regions in the C. elegans adult central nervous system, revealed presynaptic enrichment of mRNA associated with 3′-UTR binding (RBPs) and translation regulator activity [5]. This may provide an additional layer of translation control in the neurons that is stimulus-specific. Of the several RBP transcripts that were enriched in the synapse, pufs (puf-3, puf-5, puf-7, puf-8, puf-11) were the most numerous. Synaptically localized pufs were also shown to be necessary for normal positive olfactory associative memory formation. These puf RBPs are orthologs of mammalian PUM1/2 both of which are known to interact with FMRP in a collaborative, RNA-dependent manner with possible roles in synaptogenesis [170, 249]. While PUM2 has a key role in mRNA localization and translation where it restricts specific transcripts to the cell body in developing neurons, the enrichment in neurons of adult animals allude to their roles in plasticity and behavior in the axonal and presynaptic regions [141].

The importance of cis-regulatory elements in the UTRs is demonstrated in the transport of neuritin mRNA (Nrn1). Nrn1 promotes synapse formation and maintenance [81, 154, 158]. Its mRNA localizes to axons in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and hippocampal neurons, this localization changes following nerve injury [207, 236]. Nrn1 transcript localization increases in axons and decreases in the soma when subjected to axotomy. Moreover, Nrn1 3′-UTR drives its axonal localization in the hippocampal neurons (CNS); it is the 5′-UTR that is essential for the same in in DRG neurons (PNS), the latter of which promotes neurite growth post injury. These distinct events may be explained by different RBPs binding to the Nrn1 5′-UTR versus Nrn1 3′-UTR. For instance, survival of motor neuron (SMN) and HuD immunoprecipitated together while Nrn1 mRNA colocalizes with SMN in hippocampal axons making HuD a prime Nrn1 3′-UTR regulatory RBP candidate. Similarly, different RBPs may also associate with Nrn1 5′-UTR for axonal localization in the DRG neurons [147].

Trans-elements such as ZBP1/IGF2BP1 are a great example of RBPs’ role in cellular transport. It is highly expressed in the embryo and is responsible for the development of the nervous system. Defects in ZBP1 gene expression in developing neurons are associated with growth cone guidance, axonal remodeling, dendritic morphology defects, as well as smaller cerebral cortices [66, 122, 144, 162, 188, 231]. This RBP is well known for its regulation of local translation of β-actin mRNA. ZBP1 associates with β-actin mRNA in perinuclear space through its two C-terminal KH domains that bind to β-actin 3′-UTR ‘zipcode’ 54-nucleotide RNA sequence. ZBP1 KH domains, KH3 and KH4 form a pseudo-dimer with the two RNA-binding grooves on opposite sides [71, 171]. This binding event is accompanied by the RNA molecule looping around the protein leading to translationally repressed transcripts that remain so until they reach their destination at the cell periphery. At this point, the protein kinase Src phosphorylates ZBP1 to sever the ZBP1-RNA complex and promote translation [100, 238]. Thus, ZBP1 prevents premature translation of the transcript demonstrating the spatiotemporal aspect of mRNA localization and translation [159].

ZBP1 is also required for axonal localization of GAP-43 mRNA, important for axon growth and regeneration [55, 56]. GAP-43 mRNA coimmunoprecipitates with both ZBP1 and the ELAV-like RBP HuD that binds to an AU-rich regulatory element (ARE) in the 3′-UTR of GAP-43 mRNA and promotes local stabilization [19, 150]. While GAP-43 mRNA does not have a distinct ZBP1 binding zipcode, HuD binding to GAP-43 ARE is necessary and sufficient for GAP-43 mRNA axonal localization. ZBP1 and HuD RBPs post-transcriptionally regulate GAP-43 mRNA by forming a complex via the ARE element [246]. This is illustrated in Fig. 5a.

Figure 5.

(a) Localization of GAP-43 mRNA in axons. Binding of Hud and Zbp1 to the ARE element in the 3′-UTR of GAP-43 transports the mRNA to axons (adapted from [246]). (b) Localization of BDNF mRNA in dendrites. Based on the length of BDNF mRNA 3′-UTR, the factors required for dendritic localization vary. CPEB-1, CPEB-2, ELAV-2 and ELAV-4 are crucial for the dendritic localization of BDNF mRNA with short 3′-UTR, whereas CPEB1, ELAV1, ELAV3, ELAV4, FMRP and FXRP2 are required for the localization of BDNF mRNA with long 3′-UTR (adapted from data presented in [220]). (c) Formation of neuronal granules. Neuronal granules, which are transported from the soma to the nerve ending, are formed by non-covalent interaction between mRNAs and RBPs (adapted from [74]).

Complex mechanisms of localization and transport have been unearthed previously. For instance, dendritic trafficking of BDNF transcripts displays both activity dependence and transcript selectivity. Transcripts of neurotrophin BDNF and its receptor TrkB are targeted to the dendrites in cultured hippocampal neurons. BDNF is involved in regulating synaptic plasticity by enhancing synaptic transmission and is involved in hippocampal LTP (reviewed in [25, 208]). BDNF is also a well-known regulator of dendritic patterning and morphology. BDNF transcripts exist in two types of isoforms, either with long or short 3′-UTRs, as a result of its gene being processed at two different polyadenylation sites. This affects their localization to different subcellular compartments and the 3′-UTRs also carry cis-dendritic targeting signals. Transcripts with short 3′-UTRs are restricted to the soma under resting conditions, in the absence of specific neuronal cues, while those with long 3′-UTRs are targeted to both the soma and dendrites [3, 116, 220]. These differential targeting mechanisms rely on separate sets of RBPs functioning in an activity-dependent manner [1, 9, 34, 35, 165, 220, 235].

Transcripts with short 3′-UTRs are transported to the dendrites, induced by neuronal stimuli and this dendritic localization is mediated by neurotrophin NT3 and requires the RBP, cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein-1 (CPEB-1) [9, 165]. The short 3′-UTR contains cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE)-like cis-acting motifs to which CPEB-1 binds directly. As CPE-like sequences were shown to be necessary for BDNF mRNA dendritic targeting to hippocampal neurons, CPEB-1 may have a key role in BDNF mRNA targeting. In addition to CPE elements, short 3′-UTRs also contain conserved ELAV RBP binding sites, disruption of which hinders short BDNF 3′-UTR dendritic targeting. BDNF mRNA localization to dendrites seems to rely on its association with CPEB-1, CPEB-2, ELAV-2 and ELAV-4 RBPs. In contrast, long 3′-UTR targeting is more complex and relies on ELAV-1,3,4, FMRP and FXRP2 mediated BDNF-dependent release of soma-retention signals. Long 3′-UTRs also contain a highly conserved CPEB-1 binding site. Thus, BDNF mRNA dendritic targeting mechanisms are induced by different stimuli and associate with distinct sets of RBPs [165]. This is illustrated in Fig. 5b.

The coding sequence also plays pivotal roles in these mechanisms. Translin, a single-stranded DNA/RNA binding protein binds directly to the coding sequence of BDNF mRNA and this binding event is associated with constitutively active dendritic targeting of transcripts with both short and long 3′-UTRs. Translin-dependent transport of transcripts restricted to the soma can be overridden by 5′-UTR cis-elements [1, 9, 10, 34, 35, 165, 172].

Similarly, the 3′-UTR of CaMKIIα transcripts are present in short or long forms and have two CPE elements that promote mRNA transport and translational activation in dendrites. The coding sequence also contains translin-binding sites necessary for dendritic localization [98, 191]. These studies hint at a common mRNA targeting mechanism shared by different mRNAs with common functions, which utilize cis-elements that associate with distinct set of RBPs.

NEURONAL GRANULES

Neuronal granules are membrane delimited phase-separated condensates, which aid the transport of mRNA to the far ends of neurons including dendrites, axons and synapses from the cell body, to aid local translation of signaling molecules. These condensates are formed by non-covalent interactions between mRNAs and RBPs. The neuronal mRNAs that are to be transported to the distant end of neurons consist of comparatively longer UTRs. These regions act as hotspots for the binding of RBPs and other trans-factors. Apart from binding to mRNA, some of the RBPs consist of intrinsically disordered regions [214]. Studies have shown that these low complexity regions undergo assembly through pi-pi and other non-covalent interaction leading to phase separation ([217] and reviewed in [74]). Neuronal granules are illustrated in Fig. 5c.

Neuronal granules delimit themselves from the rest of the cytosol, making the mRNA inside the granule inaccessible to the cytoplasmic translational machinery. Interestingly, RBPs like Smaug1, ZBP1 themselves repress the translation of mRNA to which they are bound ([7], Anderson). More recent studies have suggested that the nuclear granules are actively transported bidirectionally. The anterograde and retrograde movement is achieved by binding of the nuclear granules to the membrane bound organelles, leading to cotransport with the organelle. Anterograde movement helps local transport of specific mRNAs involved in presynaptic activity, whereas retrograde movement is crucial for maintaining homeostasis, degradation of aging proteins and organelles in the synapse, recycling and signaling during injury (reviewed in [135]). The attachment of the nuclear granules to the organelles is achieved through specific RBPs like SMN, She2p and Annexin. Specifically, Annexin A11 has a C-terminal domain that tether to membrane lipids, PI(3,5)P2-present in lysosomes-and an N-terminal comprising low complexity regions that aid phase separation (reviewed in [178]). Mutations in annexin A11 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have been shown to compromise neuronal granules’ transport by inhibiting the binding of annexin to the lysosome [126].

The neural UTRs are considerably longer than in other cells and provide several sequence motifs for RBPs and miRNA binding. These features along with other RNA transport promoting factors contribute to RNA delivery to distal neuronal destinations. RNAs are mostly found in complexes with RBPs (RNP complexes) and of the nearly 2000 known RBPs in the human genome, some are exclusively or predominantly expressed in neurons with neuron-specific roles (ELAVL, RBFOX, FUS and FMRP) (reviewed in [41, 49]). RNP complexes along with ribosomal components form neuronal transport granules that package mRNA for transport. They exhibit constitutive bidirectional movement along axons and dendrites and selectively release mRNA for translational initiation by polysomes following neuronal depolarization [110, 113]. Transport granules are unique in that they are liquid–liquid phase separated from the rest of the liquid cytosol, unlike other conventional soluble complexes due to the multivalent and dynamic interactions between RNA and protein components with RNA binding domains such as RRM or KH domains and intrinsically disordered regions with low-complexity sequences [27, 130]. These biomolecular condensates form dynamic membrane-less organelles that enclose RNA and protein components and restrict cytosolic accessibility. When this mechanism is impaired, it is associated with several neurodegenerative diseases (reviewed in [29, 74]).

Regulation of neuronal granule transport

Activity-dependent reversible activation of local translation is important for synaptic strength, plasticity and long-term memory formation (reviewed in [109]. Neuronal stimuli at the synapse quickly induce translation of silenced mRNAs in neuronal transport granules (reviewed in [203]). Activity-dependent translation is thought to require reversible granule formation. For instance, β-actin mRNA is packaged into neuronal granules that assemble to remain translationally repressed and disassemble for localized translation due to neuronal stimuli [62].

RBP FMRP is enriched in transport granules and phase separates with RNA into liquid droplets, in vitro, via its C-terminal low-complexity disordered region (LCDR) [217]. FMRP has been demonstrated to form membraneless foci in cells and liquid droplets with RNA in vitro and the C-terminal FMRP-LCDR is necessary and sufficient for these events in vitro. FMRP typically behaves as a translational repressor in a phosphorylation-dependent manner via ribosomal stalling [156, 157]. Additionally, methylation of FMRP RGG motifs may impede ribosomal stalling and decrease its binding affinity toward G-quadruplex-containing RNAs [47, 54, 180]. While numerous studies have elucidated the mechanisms of translational control by FMRP, these mechanisms have not been clearly defined in the context of neuronal transport granules.

The abundance of FMRP in neuronal granules plays a vital role in activity-dependent mRNA translation through post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and methylation, which lead to opposing effects on translational regulation. FMRP in vitro translation inhibition and phase separation was also observed to be FMRP concentration-dependent. This is mediated by post-translational modification where FMRP phosphorylation enhances phase separation and translation inhibition while methylation opposes them. Furthermore, other translational repressors that function alongside FMRP, including neuronal eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein (4E-BP) and miRNA 125b, were sequestered into FMRP-RNA liquid droplets, which may strengthen their inhibitory activity [64, 153, 155, 214].

Regulation of local translation of silenced MRNAs

Reversible granule formation allows for repeated local translation of the same mRNA transcript that transitions from a repressed state within granules into an active state highlighting the significance of synaptic regulation of phase separation [113]. RBPs and miRNA trans-acting elements are ideal for selective and reversible inhibition of mRNA translation at synapses in response to receptor signaling (reviewed in [31, 112]). In fact, RBPs and miRNAs may cooperate to achieve rapid translational regulation [64]. For instance, FMRP associates with mammalian eIF2C2 (AGO2) and miRNAs. FMRP phosphorylation leads to AGO2-miR125a inhibitory complex formation on postsynaptic density protein (PSD-95) mRNA 3′-UTR. In contrast, gp1 mGluR stimulation causes dephosphorylation of FMRP and dissociation of AGO2 from the mRNA followed by translational activation [153].

FMRP is thought to translationally suppress specific mRNAs, including MAP1b, CaMKIIα and Arc (reviewed in [18]). FMRP is linked to the miRNA pathway as it interacts with proteins in the RNA interference silencing complex and with miRNAs [32, 103, 166, 175]. The 3′-UTR of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2A has conserved miR-125b target sequence, marking it for suppression. Additionally, loss of FMRP or AGO1 function leads to upregulation of NR2A 3′-UTR reporter. This suggests that it is regulated by FMRP and miR-125b through its 3′-UTR. NMDA receptor subunit ratio is an important factor in its receptor signaling with even subtle changes in NR2A expression mediated by RBPs and miRNAs influencing [15, 64].

The 4E-BPs bind eIF4E and downregulate the translation of many mRNAs [182]. Cytoplasmic FMRP interacting protein CYFIP1, a 4E-BP binds the cap-binding factor eIF4E and CYFIP1 is also an FMRP-interacting factor [111, 155, 189]. CYFIP1 forms a complex with the FMRP and represses activity-dependent translation through CYFIP1, a new 4E-BPh specific FMRP-target mRNAs such as MAP1B, αCaMKII and APP ([94, 232] and reviewed in [8]). The eIF4E-CYFIP1-FMRP complex is found at the synapses and synaptic activity was demonstrated to release CYFIP1 from eIF4E and 5′ end of specific mRNAs, curbing translational repression [155].

CONCLUSION

The proper function of the nervous system depends on precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression. Complex post-transcriptional mechanisms play key roles in the regulation of gene expression to ensure proper neuronal development and synaptic plasticity (reviewed in [49, 151]). PTR is essential for the processes involving RNA metabolism including AS, RNA editing, mRNA stability, mRNA localization and translation (reviewed in [40, 120]). Elucidation of PTR of mRNA targets mediated by trans-acting factors is a key step toward understanding their significance in neuronal function, homeostasis and disease.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Institute of Eminence postdoctoral fellowship grant from Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore (IE/REAC-21-0119.10 to V.D.B.); the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore intramural funds; the IA grant (IA/S/19/2/504649 to K.B.); the DBT grants (BT/PR24038/BRB/10/1693/2018 and BT/HRD-NBA-NWB/38/2019-20 to K.B.); and the Ministry of Education (MoE/STARS-1/454 to K.B., MoE/STARS-1/454 to J.J.).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Vandita D Bhat, Centre for Neuroscience, Indian Institute of Science, CV Raman Road, Bangalore 560012, Karnataka, India.

Jagannath Jayaraj, Centre for Neuroscience, Indian Institute of Science, CV Raman Road, Bangalore 560012, Karnataka, India.

Kavita Babu, Centre for Neuroscience, Indian Institute of Science, CV Raman Road, Bangalore 560012, Karnataka, India.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The images for this review were created using BioRender.com.

References

- 1.Aliaga EE, Mendoza I, Tapia-Arancibia L. Distinct subcellular localization of BDNF transcripts in cultured hypothalamic neurons and modification by neuronal activation. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2009;116:23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amir-Ahmady B, Boutz PL, Markovtsov V et al. Exon repression by polypyrimidine tract binding protein. RNA. 2005;11:699–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An JJ, Gharami K, Liao GY et al. Distinct role of long 3′ UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cell. 2008;134:175–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreadis A, Gallego ME, Nadal-Ginard B. Generation of protein isoform diversity by alternative splicing: mechanistic and biological implications. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1987;3:207–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arey RN, Kaletsky R, Murphy CT. Nervous system-wide profiling of presynaptic mRNAs reveals regulators of associative memory. Sci Rep. 2019;9:20314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athanasiadis A, Rich A, Maas S. Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baez MV, Luchelli L, Maschi D et al. Smaug1 mRNA-silencing foci respond to NMDA and modulate synapse formation. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:1141–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagni C, Greenough WT. From mRNP trafficking to spine dysmorphogenesis: the roots of fragile X syndrome. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:376–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baj G, Del Turco D, Schlaudraff J et al. Regulation of the spatial code for BDNF mRNA isoforms in the rat hippocampus following pilocarpine-treatment: a systematic analysis using laser microdissection and quantitative real-time PCR. Hippocampus. 2013;23:413–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baj G, Leone E, Chao MV et al. Spatial segregation of BDNF transcripts enables BDNF to differentially shape distinct dendritic compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16813–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballas N, Grunseich C, Lu DD et al. REST and its corepressors mediate plasticity of neuronal gene chromatin throughout neurogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:645–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bambah-Mukku D, Travaglia A, Chen DY et al. A positive autoregulatory BDNF feedback loop via C/EBPbeta mediates hippocampal memory consolidation. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12547–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bargmann CI, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;74:515–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnby G, Abbott A, Sykes N et al. Candidate-gene screening and association analysis at the autism-susceptibility locus on chromosome 16p: evidence of association at GRIN2A and ABAT. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:950–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barria A, Malinow R. NMDA receptor subunit composition controls synaptic plasticity by regulating binding to CaMKII. Neuron. 2005;48:289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass BL. RNA editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:817–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassell GJ. Fragile balance: RNA editing tunes the synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1492–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckel-Mitchener AC, Miera A, Keller R et al. Poly(A) tail length-dependent stabilization of GAP-43 mRNA by the RNA-binding protein HuD. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27996–8002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg BE, Jens M, Wang PY et al. Concentration-dependent splicing is enabled by Rbfox motifs of intermediate affinity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:901–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhalla K, Phillips HA, Crawford J et al. The de novo chromosome 16 translocations of two patients with abnormal phenotypes (mental retardation and epilepsy) disrupt the A2BP1 gene. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:308–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhogal B, Jepson JE, Savva YA et al. Modulation of dADAR-dependent RNA editing by the Drosophila fragile X mental retardation protein. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1517–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bill BR, Lowe JK, Dybuncio CT et al. Orchestration of neurodevelopmental programs by RBFOX1: implications for autism spectrum disorder. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;113:251–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonhoeffer T. Neurotrophins and activity-dependent development of the neocortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:119–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutz PL, Stoilov P, Li Q et al. A post-transcriptional regulatory switch in polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins reprograms alternative splicing in developing neurons. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1636–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS et al. Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science. 2009;324:1729–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brummer A, Yang Y, Chan TW et al. Structure-mediated modulation of mRNA abundance by A-to-I editing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calabretta S, Richard S. Emerging roles of disordered sequences in RNA-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:662–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carreira-Rosario A, Bhargava V, Hillebrand J et al. Repression of pumilio protein expression by Rbfox1 promotes germ cell differentiation. Dev Cell. 2016;36:562–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang S, Wen S, Chen D et al. Small regulatory RNAs in neurodevelopmental disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R18–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheever A, Ceman S. Phosphorylation of FMRP inhibits association with dicer. RNA. 2009;15:362–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Zubovic L, Yang F et al. Rbfox proteins regulate microRNA biogenesis by sequence-specific binding to their precursors and target downstream dicer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4381–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiaruttini C, Sonego M, Baj G et al. BDNF mRNA splice variants display activity-dependent targeting to distinct hippocampal laminae. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:11–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiaruttini C, Vicario A, Li Z et al. Dendritic trafficking of BDNF mRNA is mediated by translin and blocked by the G196A (Val66Met) mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16481–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colbert HA, Bargmann CI. Odorant-specific adaptation pathways generate olfactory plasticity in C. elegans. Neuron. 1995;14:803–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conaco C, Otto S, Han JJ et al. Reciprocal actions of REST and a microRNA promote neuronal identity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2422–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conboy JG. Developmental regulation of RNA processing by Rbfox proteins. RNA. 2017;8:e1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook D, Nuro E, Jones EV et al. FXR1P limits long-term memory, long-lasting synaptic potentiation, and de novo GluA2 translation. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1402–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbett AH. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression and human disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018;52:96–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corley M, Burns MC, Yeo GW. How RNA-binding proteins interact with RNA: molecules and mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2020;78:9–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costessi L, Devescovi G, Baralle FE et al. Brain-specific promoter and polyadenylation sites of the beta-adducin pre-mRNA generate an unusually long 3′-UTR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:243–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coutinho-Mansfield GC, Xue Y, Zhang Y et al. PTB/nPTB switch: a post-transcriptional mechanism for programming neuronal differentiation. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1573–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai J, Aoto J, Sudhof TC. Alternative splicing of presynaptic neurexins differentially controls postsynaptic NMDA and AMPA receptor responses. Neuron. 2019;102:993–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalpe G, Leclerc N, Vallee A et al. Dystonin is essential for maintaining neuronal cytoskeleton organization. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;10:243–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Damianov A, Ying Y, Lin CH et al. Rbfox proteins regulate splicing as part of a large multiprotein complex LASR. Cell. 2016;165:606–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darnell JC, Jensen KB, Jin P et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein targets G quartet mRNAs important for neuronal function. Cell. 2001;107:489–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darnell RB. RNA protein interaction in neurons. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:243–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deffit SN, Yee BA, Manning AC et al. The C. elegans neural editome reveals an ADAR target mRNA required for proper chemotaxis. elife. 2017;6:e28625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dehmelt L, Halpain S. The MAP2/tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 2005;6:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Del’Guidice T, Latapy C, Rampino A et al. FXR1P is a GSK3beta substrate regulating mood and emotion processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E4610–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desterro JM, Keegan LP, Lafarga M et al. Dynamic association of RNA-editing enzymes with the nucleolus. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1805–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dolzhanskaya N, Merz G, Aletta JM et al. Methylation regulates the intracellular protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions of FMRP. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1933–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donnelly CJ, Park M, Spillane M et al. Axonally synthesized-actin and GAP-43 proteins support distinct modes of axonal growth. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3311–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donnelly CJ, Willis DE, Xu M et al. Limited availability of ZBP1 restricts axonal mRNA localization and nerve regeneration capacity. EMBO J. 2011;30:4665–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dorsey SG, Renn CL, Carim-Todd L et al. In vivo restoration of physiological levels of truncated TrkB.T1 receptor rescues neuronal cell death in a trisomic mouse model. Neuron. 2006;51:21–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dotti CG, Sullivan CA, Banker GA. The establishment of polarity by hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1454–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dovey OM, Foster CT, Cowley SM. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), but not HDAC2, controls embryonic stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8242–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dubnau J, Chiang AS, Grady L et al. The staufen/pumilio pathway is involved in Drosophila long-term memory. Curr Biol. 2003;13:286–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Conley RR et al. Altered gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and receptor tyrosine kinase B in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:804–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ebert DH, Greenberg ME. Activity-dependent neuronal signalling and autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2013;493:327–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eckmann CR, Kraemer B, Wickens M et al. GLD-3, a bicaudal-C homolog that inhibits FBF to control germline sex determination in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2002;3:697–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edbauer D, Neilson JR, Foster KA et al. Regulation of synaptic structure and function by FMRP-associated microRNAs miR-125b and miR-132. Neuron. 2010;65:373–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. A-to-I RNA editing—immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:473–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eom T, Antar LN, Singer RH et al. Localization of a beta-actin messenger ribonucleoprotein complex with zipcode-binding protein modulates the density of dendritic filopodia and filopodial synapses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10433–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ernst C, Deleva V, Deng X et al. Alternative splicing, methylation state, and expression profile of tropomyosin-related kinase B in the frontal cortex of suicide completers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM et al. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat Med. 2008;14:723–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Faghihi MA, Zhang M, Huang J et al. Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fallini C, Donlin-Asp PG, Rouanet JP et al. Deficiency of the survival of motor neuron protein impairs mRNA localization and local translation in the growth cone of motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2016;36:3811–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Farina KL, Huttelmaier S, Musunuru K et al. Two ZBP1 KH domains facilitate beta-actin mRNA localization, granule formation, and cytoskeletal attachment. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:77–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fatemi SH, Folsom TD. Dysregulation of fragile x mental retardation protein and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in superior frontal cortex of individuals with autism: a postmortem brain study. Mol Autism. 2011;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fenner ME, Achim CL, Fenner BM. Expression of full-length and truncated trkB in human striatum and substantia nigra neurons: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Mol Histol. 2014;45:349–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fernandopulle MS, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Ward ME. RNA transport and local translation in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:622–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrer I, Marin C, Rey MJ et al. BDNF and full-length and truncated TrkB expression in Alzheimer disease. Implications in therapeutic strategies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:729–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Filippini A, Bonini D, Lacoux C et al. Absence of the fragile X mental retardation protein results in defects of RNA editing of neuronal mRNAs in mouse. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1580–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Finkel RS, Chiriboga CA, Vajsar J et al. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: a phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet. 2016;388:3017–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fogel BL, Wexler E, Wahnich A et al. RBFOX1 regulates both splicing and transcriptional networks in human neuronal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4171–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Freund EC, Sapiro AL, Li Q et al. Unbiased identification of trans regulators of ADAR and A-to-I RNA editing. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fu XD, Ares MJ. Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:689–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujino T, Leslie JH, Eavri R et al. CPG15 regulates synapse stability in the developing and adult brain. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2674–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gabel HW, Kinde B, Stroud H et al. Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature. 2015;522:89–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]