Abstract

The transcription factor GATA-2 is expressed at high levels in the nonneural ectoderm of the Xenopus embryo at neurula stages, with lower amounts of RNA present in the ventral mesoderm and endoderm. The promoter of the GATA-2 gene contains an inverted CCAAT box conserved among Xenopus laevis, humans, chickens, and mice. We have shown that this sequence is essential for GATA-2 transcription during early development and that the factor binding it is maternal. The DNA-binding activity of this factor is detectable in nuclei and chromatin bound only when zygotic GATA-2 transcription starts. Here we report the characterization of this factor, which we call CBTF (CCAAT box transcription factor). CBTF activity mainly appears late in oogenesis, when it is nuclear, and the complex has multiple subunits. We have identified one subunit of the factor as p122, a Xenopus double-stranded-RNA-binding protein. The p122 protein is perinuclear during early embryonic development but moves from the cytoplasm into the nuclei of embryonic cells at stage 9, prior to the detection of CBTF activity in the nucleus. Thus, the accumulation of CBTF activity in the nucleus is a multistep process. We show that the p122 protein is expressed mainly in the ectoderm. Expression of p122 mRNA is more restricted, mainly to the anterior ectoderm and mesoderm and to the neural tube. Two properties of CBTF, its dual role and its cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation, are shared with other vertebrate maternal transcription factors and may be general properties of these proteins.

Cellular differentiation during early vertebrate development is dependent upon the regulated expression of tissue-restricted transcription factors which, in turn, act to determine cell fate. GATA-2 is one such protein. It is a member of a family of six vertebrate zinc finger transcription factors characterized by the ability to bind to the DNA sequence WGATAR (16, 25, 29, 35, 73). Various members of this family have been shown to control tissue-specific gene expression principally in hematopoietic cells (47) and heart and endodermally derived tissues (19, 57). GATA-2 expression has been studied in mice (14, 61), chickens (73), zebrafish (1, 39) and Xenopus laevis (7, 8, 27, 49, 66, 77), where it has been found in hematopoietic precursors, immature erythroid cells, proliferating mast cells, and the central nervous system. The function of GATA-2 has been tested by the creation of homozygous null mutant mice by homologous recombination. These mice lack all hematopoietic lineages (61). This is most likely a result of the need for GATA-2 for both the survival and proliferation of early progenitors of these lineages (62).

In the developing Xenopus embryo, GATA-2 is present as a maternal mRNA and protein (27, 49, 66, 77). Zygotic transcription of GATA-2 commences after the mid-blastula transition (MBT) at the start of gastrulation (stage 10.5) and is up-regulated by BMP-4 (34, 55, 75). By the end of gastrulation at stage 15, in situ hybridization studies show expression to be in all three germ layers (at its highest levels in ectoderm), extending ventrally from the edge of the neural plate (66). Later, expression becomes more restricted to the ventral blood islands, the dorsal-lateral plate mesoderm, and particular regions of the central nervous system (7). Accumulation of GATA-2 mRNA can be inhibited in gastrula stage embryo explants by coculturing with either dorsal marginal zones or the dorsalizing and neural inducing factor noggin (59, 66), suggesting that the localization of GATA-2 to the ventral region is a consequence of negative control during dorsalization and neural induction, events which inactivate BMP-4 (51, 76). Evidence has shown that in the nonneural ectoderm of Xenopus, GATA-2 is patterned, with high levels of mRNA found in the anterior region becoming progressively lower posteriorly (53). Negative regulation of GATA-2 transcription by fibroblast growth factor in the posterior region may be at least partially responsible for this expression pattern. Although the signals controlling expression of GATA-2 in early Xenopus development have been studied extensively, less is known of the function of GATA-2 in early development outside the blood lineages. Recently, this has been investigated in Xenopus by expression of a dominant negative form of the protein (60). The results obtained show an important role for GATA-2 in ventral mesoderm formation.

The trans-acting factors controlling GATA-2 expression are also less well defined than the signaling molecules. Regulatory regions of the GATA-2 gene have been identified in Xenopus (8), humans (17), zebrafish (39), and mice (41). In Xenopus, analysis of the GATA-2 promoter has been confined to early stages of development (prior to neurula stages), when the major site of GATA-2 transcription is in the ectoderm. A 1.65-kb region of DNA upstream from the start of transcription directed correct temporal and spatial regulation of a linked reporter gene. Subsequent deletion analysis revealed that sequences between −66 and −31 in the promoter were the minimum needed for correct temporal control of GATA-2 transcription. Within this region is a CCAAT box in a reverse orientation, and we have shown (48) that a maternal CCAAT box transcription factor (CBTF) binds to this site and that a single point mutation (CCgAT) abolishes its binding. Introducing this mutation into the 1.65-kb GATA-2 promoter inactivates it; thus, CBTF is essential for GATA-2 transcription. Although CBTF is present in the embryo prior to zygotic GATA-2 transcription, its activity, as assayed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), is not detectable in the nucleus or chromatin-bound fraction until stage 10.5, when GATA-2 transcription begins (8). The crucial role of CBTF in GATA-2 regulation is emphasized by the conservation of its binding site between species. An extended homology around the Xenopus CCAAT box is found in the human GATA-2 promoter (17). Similarly, an extended homology is found in the general promoter of the murine GATA-2 gene described by Yamamoto and colleagues (41); this gene has a second upstream promoter which is specific for hematopoietic cells. Assuming that Xenopus also has two GATA-2 promoters, it is then very likely that the one previously described and under investigation here (8) corresponds to the general mouse promoter.

CBTF is thus a maternal transcription factor whose activity is tightly regulated, and while it is becoming clear that some maternal transcription factors have vital roles in patterning the vertebrate embryo (22, 23, 36, 37, 44), the extent of their involvement in transcription control after zygotic gene activation remains unclear. Despite the presence of maternal transcription factors, zygotic expression is suppressed in Xenopus until the MBT. Studies have suggested that a major component of this suppression is competition between transcription factors and nucleosomes for binding of DNA (50, 52) and that the decrease in the pool of free histones in the developing embryo at the MBT allows transcription factors to bind and, thus, zygotic transcription to commence. It is likely, however, that part of the pre-MBT suppression is due to altered affinity of maternal transcription factors for DNA or their altered access to DNA, although the evidence for this is controversial (2). Once zygotic gene activation has occurred, the transcription factors present, including those maternally derived, which regulate genes later in development must be under stringent control to prevent aberrant transcription of their target genes. Holding a transcription factor in the cytoplasm is a common form of control in both invertebrates and vertebrates (67) and has been reported for several Xenopus DNA-binding proteins (6, 8, 30, 40, 55, 68). This form of transcription factor regulation has a critical role in regulating development; for example, when β-catenin accumulates in the nucleus interacting with XTCF-3, thus forming a functional transcription factor and a dorsalizing center (22, 44), and when proteins of the SMAD family become nuclear in response to transforming growth factor β stimulation (23, 37, 38).

To (i) determine the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of GATA-2 transcription and, hence, the control of downstream processes, for example, commitment to ventral fate, particularly the blood islands, and (ii) further investigate the role and control of a maternal transcription factor in vertebrates, we have commenced the biochemical characterization of CBTF. Assaying CBTF activity during development shows that most appears late in oogenesis, when the activity is confined to the nucleus (germinal vesicle). We identify the number and sizes of the CBTF subunits; furthermore, we identify the cDNA encoding one of these subunits and demonstrate that the encoded protein (p122) translocates from the cytoplasm to the nuclei of embryonic cells between stages 8 and 9 of development. p122 is a maternal double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding protein (5) and is detectable throughout the ectoderm and, to a lesser extent, the mesoderm. Expression of p122 mRNA is more restricted, mainly to the anterior ectoderm and mesoderm and to the neural tube. These data show that CBTF, a vertebrate maternal transcription factor, has at least two functions and undergoes cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation. Taken together with the work of others, the data presented here suggest that both of the above characteristics are widespread among the members of this class of molecules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Embryos and RNA injections.

X. laevis females were obtained from Nasco and maintained at a temperature of 21°C. They were fed twice weekly on frog pellets (Blades Biologicals, Kent, England). Male frogs were also from Blades. Embryos were prepared and injected with RNA as described by Gove et al. (19). RNA for injections was prepared by using an Ambion Message Machine kit. The activity of the RNA was tested in reticulocyte lysate (Promega). The untagged RNA was slightly more active than that encoding myc-tagged p122. Staging of embryos was carried out in accordance with the Normal Table (43).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization.

p122 antisense and sense digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were transcribed from the partial cDNA described. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed on staged embryos as described by Harland (21) with the modifications of Bertwistle et al. (7). Photomicrographs were taken with a Nikon SMZ-U stereomicroscope by using a Nikon U-III camera.

Immunocytochemistry.

Staged embryos were fixed as described by Harland (21), bleached with a solution of 5% formamide, 0.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and 10% H2O2 for 5 to 10 min, and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). Embryos were preincubated in PBST containing 20% goat serum for 2 h and then transferred to primary antibody solution (anti-p122 serum diluted 1/1,000 in PBST containing 20% goat serum) for 16 h. The embryos were then washed five times for 1 h each time with PBST, preincubated in PBST containing 20% goat serum for 2 h, and then transferred to secondary antibody solution (alkaline phosphatase [AP]- or horseradish peroxidase [HRP]-linked anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G diluted 1/1,000 or 1/400, respectively, in PBST containing 20% goat serum) for 16 h. The embryos were washed five times for 1 h each time with PBST and developed with BM purple (AP substrate; Boehringer Mannheim) or Fast DAB (HRP substrate; Sigma). The reaction was stopped by the addition of Tris-EDTA, and the embryos were refixed and stored in methanol at −20°C.

Sectioning of embryos.

Following whole-mount in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry, embryos were embedded in a gelatin-albumin mixture as described by Gove et al. (19), and 50-μm sections were cut with a vibratome. Embryo sections were photographed on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope with differential interference contrast optics by using a Nikon U-III camera system.

EMSA.

Oocyte analysis was carried out as described by Brewer et al. (8). For embryo analysis, pools of 50 embryos were homogenized in 10 volumes of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–2 mM MgCl2–10 mM β-glycerophosphate–2 mM levamisol–Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Boehringer Mannheim). Yolk proteins were removed by extraction with an equal volume of 1,1,2-trichlorotrifluoroethane (Freon) (72), and extracts were used immediately. For both oocyte and embryo analyses of CBTF, each assay mixture contained 4 fmol of a ds oligonucleotide probe, one strand of which had been labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by polynucleotide kinase prior to annealing; 500 ng of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC) (Pharmacia); 4% (wt/vol) Ficoll; 20 mM HEPES; 2 mM MgCl2; 50 mM NaCl; and extract as indicated in the figure legends, which was added last. When required, a competitor oligonucleotide was freshly annealed and 200 fmol was added to the assay mixture. The assay mixture was incubated at 0°C for 15 min prior to separation on a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× Tris-borate-EDTA. Separation was carried out at 200 V for 105 min at 4°C. EMSA of nuclear factor Y (NF-Y) was performed exactly as described in Dorn et al. (11), by using 4 fmol of a double-stranded probe corresponding to the Y box from the murine major histocompatibility complex class II E-kappa-alpha gene (12) and 500 ng of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC). The band which was self-competed with a 500-fold excess of the unlabeled probe, but not with an unrelated sequence, was identified as NF-Y. Gels were then dried and subjected to autoradiography at −70°C for 1 to 20 h.

BrdU cross-linking.

Embryo extracts were prepared and incubated essentially as described above, by using 40 fmol of a bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-substituted ds oligonucleotide and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC) for each 20 μl of extract. The assay mixture was subjected to UV irradiation at 254 nm for 15 min, separated by preparative EMSA as described above, and subjected to autoradiography for 1 h at 4°C. The region of the gel corresponding to CBTF was removed, crushed, resuspended in 500 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer, and incubated at 50°C for 16 h. The gel was removed from the solution, and protein-DNA complexes were precipitated with 300 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.8) and 2.5 volumes of ethanol. The protein-DNA complexes were separated on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography for 2 to 7 days.

Immunodepletion of EMSA reactions.

Embryo extracts were prepared and incubated essentially as described above, with the addition of Nonidet P-40 to a final concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol). For the immunodepletion assays, 10 μl of extract was incubated with 3 to 5 μl of antiserum or preimmune serum for 1 h at 20°C prior to probe addition and at 4°C for 15 min after probe addition and then separated as described above.

Isolation of CCAAT-binding cDNAs.

A cDNA library prepared in λZAPII from mRNA from animal pole explants taken at stage 7.5 and cultured to gastrula stages (a gift from Alison Snape and Jim Smith) was probed by using the −66 to −31 sequence of the GATA-2 promoter as previously described (64). The binding and washing conditions were those previously used to identify a CCAAT factor (33).

Western blotting.

Western blotting was carried out as described by Bass et al. (5).

RESULTS

CBTF is a newly described multisubunit CCAAT box factor which is made late in oogenesis.

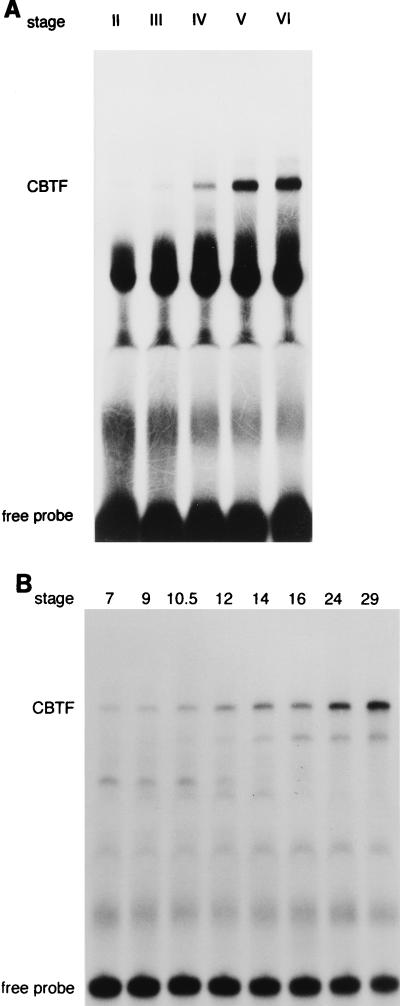

To discover whether our CBTF corresponds to any previously known CBTF, we first assayed the time course of CBTF activity in development. This allowed comparison with a CCAAT factor known to be present maternally in Xenopus, FRGY2, which decreases in abundance during oogenesis (69). This was particularly important in view of the homology between the CBTF binding site and that of FRG Y2 (8, 69). We therefore made whole-oocyte or embryo extracts and assayed CBTF activity by EMSA. CBTF activity is detectable from stage II of oogenesis, the earliest stage that we could isolate (Fig. 1A). A small increase in level was detected at stage III, a further small increase was seen at stage IV, the greatest increase occurred between stages IV and V, and a further small increase occurred by stage VI. At stage VI, CBTF activity was detected only in the nuclei of oocytes (see Fig. 7). During embryonic development, no change in CBTF activity is seen until after the start of gastrulation; activity then increases steadily to the latest stage (stage 29) which we have analyzed (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

CBTF activity in oogenesis and embryonic development. Oocytes from a single Xenopus female were manually defolliculated and staged as described by Smith et al. (58). Embryos were prepared from eggs laid by a single Xenopus female and fertilized with crushed testes from a single male. Sets of 20 oocytes or embryos were homogenized, and yolk proteins were removed by Freon extraction. Extract equivalent to one-half oocyte (A) or embryo (B) from the stages shown was then analyzed by EMSA using a probe from −66 to −31 of the GATA-2 promoter. The identity of CBTF was confirmed by competition with wild-type (CCAAT core) and mutant (CCgAT core) oligonucleotides (data not shown).

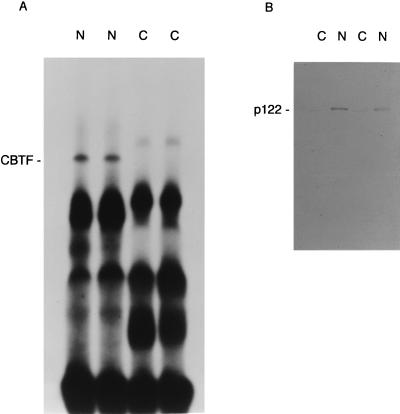

FIG. 7.

CBTF is nuclear in oocytes, whereas p122 is detected in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Duplicate sets of 20 oocytes from a single Xenopus female were defolliculated manually and dissected into nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) fractions. Yolk proteins were removed by Freon extraction, and the CBTF activity in each fraction (equivalent to the nucleus or cytoplasm from one-half oocyte) was assayed by EMSA (A). The same fractions (equivalent to the nucleus or cytoplasm from two oocytes) were also assayed for p122 by Western blotting (B).

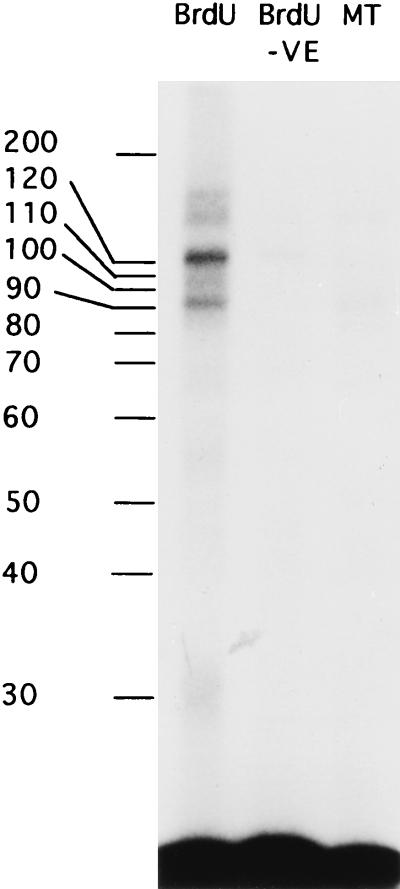

These data show that CBTF is not expressed in the same temporal pattern as FRGY2. However, to discover whether CBTF is related to any other, previously identified transcription factors, we used UV cross-linking to investigate the sizes of its subunits. We chose unfractionated oocyte extract as our protein source to avoid the possibility of loss of particular protein components of the factor. Oocyte extract was mixed with either a BrdU-substituted wild-type (CCAAT) or mutant (CCgAT) probe and exposed to UV irradiation. Specific and nonspecific complexes, as determined by competition with unlabelled wild-type or mutant oligonucleotides, were then separated by preparative EMSA. The covalently linked, specific DNA-protein complexes were then separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 2). The complexes were only seen when the wild-type probe was used, thus confirming their identity as components of CBTF. Two major bands were observed with apparent molecular masses of approximately 120 and 90 kDa; a number of weak but specific bands were also apparent at molecular masses of 160, 55, and 30 kDa (Fig. 2). The nonstoichiometric nature of the bands observed may simply reflect differing efficiencies of cross-linking or be due to the presence of two highly related complexes which share a number of subunits. Separate experimental evidence suggests that the latter is the case (45). Treatment of the complexes with DNase I prior to running of the SDS-PAGE resulted in only the two strong complexes being visible but little change in their mobility (data not shown). CBTF is thus a multisubunit complex whose major components are considerably larger than those of previously described CCAAT factors (4, 42, 47), with the exception of the 114-kDa CCAAT box-binding factor, which has only a single known subunit (33).

FIG. 2.

BrdU cross-linking of CBTF. Oocyte extract was incubated with a BrdU-substituted wild-type (CCAAT core, BrdU) or mutant (CCgAT core, MT) oligonucleotide under the conditions used for EMSA (see Materials and Methods). After incubation, the solutions were exposed to UV irradiation or left on ice (BrdU −VE). The CBTF complex was then isolated by preparative EMSA, and the equivalent region of the EMSA gel for the mutant probe was also cut out. The complex was then eluted, precipitated, and run on SDS-PAGE. The molecular size markers shown are a 10-kDa ladder (Gibco Bethesda Research Laboratories). The covalently linked protein-DNA complexes were then visualized by autoradiography.

dsRNA-binding protein p122 is a component of CBTF.

To confirm CBTF’s novelty and to identify the proteins involved in this complex, we used a direct screening method to isolate candidate cDNAs encoding subunits of the factor. A gastrula stage animal cap cDNA expression library was screened by using the CBTF binding site. Four hundred thousand plaques were screened initially, from which 12 positives were isolated. In the third round of screening, when the isolates were plaque pure, the filters were cut in half, one half was probed with the wild-type sequence, and the other was probed with the mutant. Three showed specific binding, and these were subcloned and sequenced. One of these showed identity to a known Xenopus dsRNA-binding protein (variously named 4F, ubp4, or p122). It was a partial cDNA, corresponding to nucleotides 1338 to 2527 from the published sequence (5); this region contains the dsRNA-binding motifs of p122.

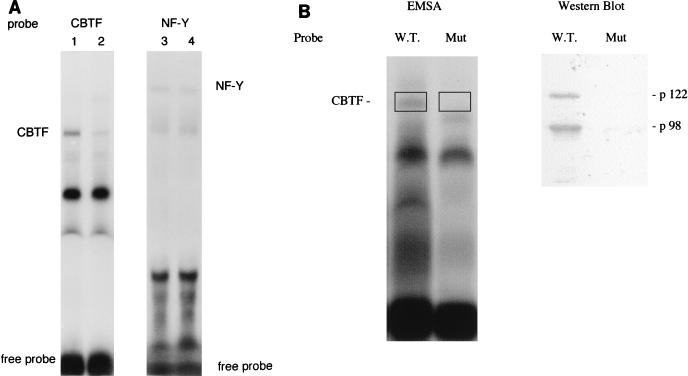

To test whether p122 is genuinely a component of CBTF, we were able to take advantage of the availability of an antibody to this protein. Oocyte extract was mixed with either preimmune serum or antiserum (kindly provided by B. Bass), and CBTF was subsequently assayed by EMSA. The antiserum blocked formation of the CBTF-DNA complex specifically (Fig. 3). As a control for the antiserum-degrading proteins within oocyte extract, a second CCAAT factor (NF-Y) was assayed and found to be unaffected (Fig. 3A). Preparative EMSA (74) was carried out by using equal amounts of the same embryo extract for both wild-type and mutant CBTF binding sites. This was followed by Western blotting of the purified protein to test for the presence of p122 in the CBTF complex. In three experiments, protein prepared from the region of the EMSA gel corresponding to the CBTF band contained very much greater levels of p122 and p98 when the wild-type (CCAAT) probe was used in the EMSA reaction than when the mutant (CCgAT) was used (Fig. 3B). Again, this strongly suggests that p122 (and also its variant p98) binds to the CCAAT region of the GATA-2 promoter specifically and is part of the CBTF complex. Nonetheless, it remained possible that an immunologically related protein was the genuine CBTF component. To eliminate this possibility, we took a second approach. We injected fertilized eggs with synthetic RNA encoding the full-length dsRNA-binding protein or one encoding the same protein with a myc epitope at the N terminus (kindly provided by M. Wormington). The embryos were allowed to develop to stage 15 to ensure that these RNAs had been translated and had had the opportunity to be incorporated into CBTF. Protein was subsequently prepared from these embryos and, after this had been incubated with various amounts of purified antibody recognizing the myc epitope, CBTF was assayed by EMSA (Fig. 4). When the epitope-tagged protein was expressed, incubation with the antibody decreased formation of the CBTF-DNA complex between 50 and 75% in three experiments (the CBTF complex detected by EMSA was estimated by PhosphorImager analysis). When the untagged protein was expressed, incubation with antibody reduced complex formation less than 5% in all three experiments (Fig. 4, compare lanes 4 and 10). p122 has not been reported to be a subunit of a CCAAT box factor, thus confirming that CBTF has not been characterized previously.

FIG. 3.

(A) Immunodepletion of embryo extracts by anti-p122 antibody. Extract from pre-MBT embryos was incubated with 3 μl of preimmune serum (lanes 1 and 3) or anti-p122 serum (lanes 2 and 4). The extract was subsequently analyzed for CBTF or NF-Y activity by EMSA, and the specificity of these complexes was confirmed by competition with a 200-fold excess of an unlabeled probe oligonucleotide (data not shown). (B) Preparative EMSA of CBTF and subsequent detection of p122 by Western blotting. Extract from 40 embryos was incubated with 40 fmol of a GATA-2 promoter probe (see Materials and Methods) containing the core sequence CCAAT (W.T.) or CCgAT (Mut) in the presence of 40 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC). Following fractionation by preparative EMSA, the bands were visualized by autoradiography of the wet gel, and the region corresponding to CBTF, which was confirmed by competition, was cut out (rectangles). Protein was recovered from the gel slices and run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, which was analyzed for p122 by Western blotting. Images were processed on a Macintosh G3 using Adobe Photoshop and Microsoft Powerpoint.

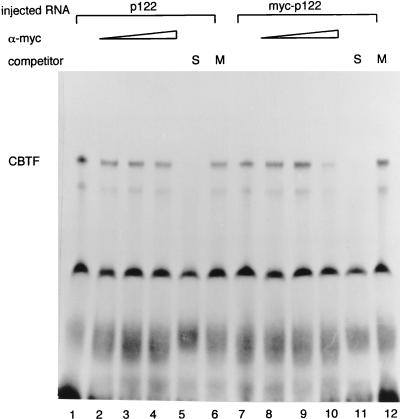

FIG. 4.

Immunodepletion of extracts from embryos expressing ectopic p122 and myc-p122 by anti-myc antibody. Embryos were injected with 200 pg of synthetic RNA encoding p122 (lanes 1 to 6) or myc epitope-tagged p122 (lanes 7 to 12) and allowed to develop to stage 15. Extracts were then prepared, and these were incubated with 0 to 5 μl of purified anti-myc epitope antibody (a gift from Pamela Taylor-Harris); CBTF was subsequently assayed by EMSA. To confirm that the complexes assayed were CBTF, extracts from injected embryos were assayed in the presence of a 100-fold excess of a wild-type (CCAAT core, S) or mutant (CCgAT core, M) oligonucleotide.

The p122 subunit of CBTF is expressed mainly in the ectoderm.

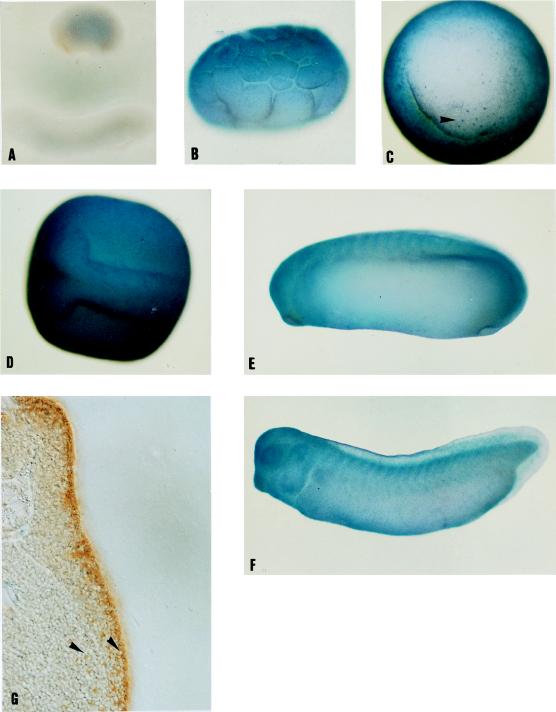

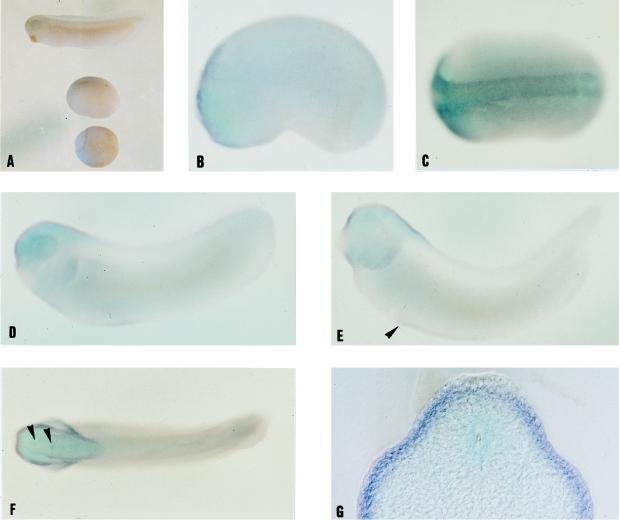

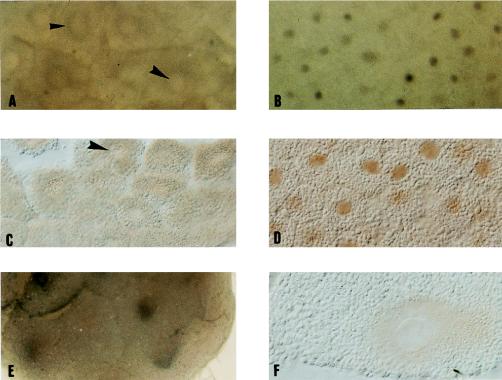

To study the relationship between the regions expressing GATA-2 and those expressing p122, we used the anti-p122 serum for immunocytochemistry (Fig. 5A to G). Controls using the preimmune serum showed no staining (Fig. 5A). Maternal p122 was detected mainly in the animal half of the blastula embryo (Fig. 5B), the prospective ectoderm and mesoderm, and this is where expression of the protein remained up to stage 29, the latest stage which we examined. p122 was found throughout the ectoderm in all stages we examined. The less highly stained lateral regions of the embryos in Fig. 5E and F clearly contained p122 when seen in sections (Fig. 5G and data not shown). Lower levels of the protein were detectable in the mesoderm (in Fig. 5G, the border between ectoderm and mesoderm is indicated by an arrowhead) and in a few cells of the endoderm (Fig. 5C and G, arrowheads). The expression of p122 mRNA was investigated by whole-mount in situ hybridization (Fig. 6). With this technique, p122 mRNA was undetectable until neurula stages, when it was seen in the anterior of the embryo and neural tissue (Fig. 6B and C), and a control using a sense RNA probe showed no staining (Fig. 6A). The levels of expression appeared genuinely low, and we achieved much higher levels of staining by using probes for other mRNAs similar in length and digoxigenin-UTP incorporation. Later, expression was found throughout the head and anterior neural tissue, excepting the cement gland (Fig. 6D and E). Less strong but specific staining was also evident in the region of the ventral blood islands (arrowhead in Fig. 6E). The dorsal view of a stage 32 embryo showed heavy staining in the eyes and anterior region of the head together with two regions of increased expression in the brain (Fig. 6F, arrowhead). Sections through the stage 32 embryos (Fig. 6G, through the more posterior region indicated by the arrowhead in Fig. 6F; Fig. 6H, just posterior to the head) revealed that the highest levels of p122 mRNA expression are found in the ectoderm and that p122 mRNA can also be detected in the mesoderm and neural tube.

FIG. 5.

p122 protein is expressed mainly in the ectoderm. Embryos were analyzed for p122 expression by immunocytochemistry using antiserum from Brenda Bass and visualized by BM purple staining of an AP-linked secondary antibody at stage 6.5 (lateral view) (B), stage 10.5 (vegetal view) (C), stage 17 (dorsal view) (D), stage 26 (E), and stage 30 (F) and DAB staining of an HRP-linked secondary antibody at stage 29 (G). The dorsal lip is clearly visible in C. Anterior is to the left in A and D to F, and dorsal is to the top in lateral views and the section (A, E, F, and G). The 50-μm section shown was taken from the trunk, posterior to the gill arches (G). Incubation with preimmune serum replacing antiserum showed no staining at stages 6 to 30 (A and data not shown). The arrowhead in C shows a p122-stained endodermal cell, and that in G indicates the boundary between the ectoderm and the mesoderm and a p122-stained endodermal cell.

FIG. 6.

p122 mRNA is expressed mainly in the ectoderm. Embryos were probed for p122 by whole-mount in situ hybridization at stage 19 (lateral view) (B); stage 19 (dorsal view (C), stage 28 (lateral view) (D), stage 32 (lateral view) (E), stage 32 (dorsal view) (F), and stage 29 followed by transverse sectioning (G and H). Anterior is to the left in A to F, and dorsal is to the top in lateral views. The 50-μm sections shown were taken as follows: G, through the posterior region indicated by the arrowhead in F; H, just posterior to the head. In situ hybridization with a sense probe showed no staining in stage 11 to 30 embryos (A). The arrowhead in E indicates the extent anteriorly to which p122 mRNA is detectable in the region of the ventral blood islands, and that in F indicates the region of increased staining in the brain.

p122 is present in the cytoplasm and nuclei of oocytes, but CBTF is solely nuclear.

We have previously shown that CBTF DNA-binding activity becomes detectable in nuclear extracts and in the chromatin-bound fraction only when these are prepared from embryos taken at, or after, the formation of the dorsal lip at stage 10.5 (8). Many proteins which undergo such a shift in localization are found in the oocyte nucleus (13). We therefore manually dissected oocyte nuclei and assayed CBTF activity in extracts of the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 7A). In duplicate samples, CBTF activity was detected only in the nucleus. We used Western blotting to test whether p122 is also nuclear, and although the majority was, p122 was detectable at low levels in the oocyte cytoplasm (Fig. 7B).

p122 translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus during embryonic development prior to detection of nuclear CBTF activity.

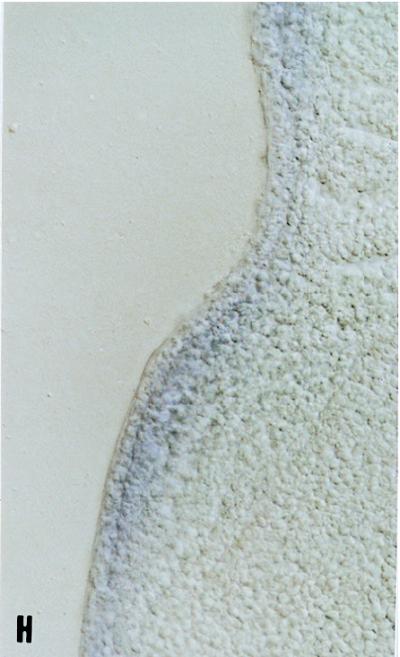

We next used immunocytochemistry to test whether translocation of p122 caused CBTF to re-enter the nucleus at the start of gastrulation. At stage 8 in whole-embryo samples or sections (Fig. 8A and C, respectively), the nuclei (large arrows) can be seen as clear, surrounded by cytoplasm staining positive for p122. In contrast, at stage 9 (Fig. 8B and D) the majority of p122 becomes nuclear, although some staining is clearly retained in the cytoplasm. Thus, p122 moves from being cytoplasmic to predominantly nuclear between stages 8 and 9, some 4 h prior to the detection of CBTF DNA-binding activity in the nucleus. During the course of these investigations, we noted that CBTF was perinuclear in early embryos (Fig. 8E and F; also 8A, small arrow). Possible mechanisms underlying the processes giving rise to these observations are discussed below.

FIG. 8.

p122 becomes nuclear at stage 9 of Xenopus development. Embryos were analyzed for p122 expression by immunocytochemistry using anti-p122 serum from Brenda Bass, visualized by DAB staining of an HRP-linked secondary antibody at stages 8 (A and C), 9 (B and D), and 5 (E and F). A and B show animal pole cells of whole embryos. C and D show 50-μm sections of the same regions. E shows an animal view of the embryo from which the section in F was taken, and F shows a single cell. The large arrowheads in A and C show nuclei, while the small arrowhead in A indicates the stronger staining observed around the nucleus prior to translocation.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of CBTF has revealed that a previously undescribed CCAAT box transcription factor (CBTF) regulates the activity of the GATA-2 gene during early development (8); the factor is a multisubunit complex which is made late in oogenesis, when it is nuclear. One subunit of CBTF has been identified as dsRNA-binding protein p122; during embryonic development, this becomes nuclear prior to the detection of nuclear CBTF activity. Expression of the p122 protein is highest in the ectoderm but is also detectable in the mesoderm, as is its mRNA.

CBTF has not been characterized before.

We have analyzed CBTF activity throughout oogenesis and early embryonic development. CBTF activity appears mainly late in oogenesis, as does XLPOU-60 (68). This is not always so for maternal transcription factors; for example, FRGY2 and XSox-3 are made early (28, 69). These data show that CBTF has an activity profile which differs markedly from the amount of FRGY2 protein during oogenesis and suggests that they are distinct despite the similarity between their binding sites (for example, 11 of 12 bases between the CBTF site in the GATA-2 promoter and the NF-Y site in the tk promoter). The level of CBTF activity increases steadily from the maternal level during development. However, the region of the embryo expressing p122 protein far exceeds that expressing the mRNA, strongly suggesting that this protein is stable in embryos and that the maternal contribution to the level of CBTF is a major one well into development. Persistence of protein has also been observed for the Oct-1 transcription factor in Xenopus embryos (63). Two further pieces of evidence support the premise that CBTF has not been characterized previously. First, the subunit sizes are different from those reported for other CCAAT-binding proteins, and these are generally well conserved during evolution (9). Second, we have carried out a number of chemical footprinting and interference techniques on CBTF-DNA complexes (46) and found that the region protected by CBTF extends further from the CCAAT core than reported for any other CCAAT factor. The final piece of evidence that CBTF is not a previously described CCAAT-binding protein comes from the fact that one of its subunits has been identified as p122, a dsRNA-binding protein.

A subunit of CBTF has two functions.

Previous work has shown that p122 contains two dsRNA-binding motifs in addition to an auxiliary domain which is rich in arginine and glycine; the RNA-binding domain has been mapped to the dsRNA-binding motifs (5). p122 binds only poorly to nonspecific DNA, and analysis of p122 expression showed that two transcripts are present in oocytes (5). These may represent the two genes present in this pseudotetraploid species or alternative splice variants. Two proteins were also observed on Western blotting of embryo extracts at molecular masses of 120 and 98 kDa. As these comigrate in SDS-PAGE precisely with the major species which we observe in CBTF upon cross-linking (45) and are both specifically detected by preparative EMSA, it is highly likely that both variants of the protein can be part of the CBTF complex. Functional analysis of p122 has recently been undertaken by Wormington and coworkers (70), and it has been shown to be involved in the masking of maternal mRNAs. A human protein with a high degree of homology to p122 (68% identity, 81% homology) has been identified. This has been shown to be a part of a protein complex which binds to the NF-AT sequence of the interleukin-2 promoter (10, 26). However, the bound DNA sequence has no homology to the binding site of CBTF. As the human NF90 protein that is homologous to Xenopus p122 has a partner in the NF-AT complex, it is possible that the distinction between their binding sites is a result of p122 and NF90 forming different complexes with disparate DNA-binding specificities. A second possibility is that these two proteins represent distinct members of a family of related transcription regulatory or dsRNA-binding proteins, again having different DNA-binding specificities.

CBTF and p122 are expressed in regions where GATA-2 is not transcribed.

We have used an antibody to p122 to identify the regions of the embryo in which p122 and its shorter variant p98 are expressed. Although this antiserum recognizes both variant forms of the protein, Western blotting of dissected embryo extracts has shown that both are present in all regions of the embryo tested so far. The protein is confined mainly to the prospective ectoderm and mesoderm at blastula stages, a pattern that has been observed before for maternal transcription factors in Xenopus, for example, XLPOU-60 (68). p122 is present in all cells where GATA-2 transcription is activated, but its expression also extends beyond these areas. For example, p122 is in the neural ectoderm at neurula stages, a region where GATA-2 is not expressed (66). Such expression may reflect the dual role of p122; for example, it may only be in the CBTF complex in areas where GATA-2 is expressed, while elsewhere it is carrying out RNA-binding functions or is part of a separate transcription factor. This is unlikely, however, since CBTF DNA-binding activity is detectable in the chromatin-bound fraction of dissected neural plates of stage 17 (neurula) embryos (45), the cells of which do not express GATA-2. Thus, the extensive region expressing p122 and CBTF activity probably reflects a role in regulating the transcription of a number of genes (and possibly that of p122 as an RNA-binding protein). Other elements in the GATA-2 promoter (8) must then restrict the regions of the ectoderm and mesoderm where this gene is transcribed.

Subcellular localizations of CBTF and p122 are not always identical.

When we assayed CBTF activity in oocytes, it was only detectable in the nuclear fraction; however, p122 was detectable in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The latter result is not in accord with the findings of Bass et al. (5), who reported no p122 in the oocyte cytoplasm. This difference is most likely due to sensitivity, as the amount of p122 detected in the cytoplasm is much less than that in the nucleus. However, we cannot detect CBTF activity in the cytoplasm, even on prolonged exposure of the EMSA gel; this strongly suggests that p122 is not always a part of an active CBTF complex. This observation, while it is possibly due to CBTF having a low affinity for its binding site, might be expected for a protein with a second function. During embryonic development, the appearance of p122 in nuclei some 4 h before the detection of CBTF activity there is, however, unexpected. This is highly unlikely to reflect the time taken to build up a sufficient quantity of CBTF in the nucleus, as while immunocytochemistry must be regarded as, at best, semiquantitative, it is clear that the bulk of p122 is in the nucleus at stage 9, when we estimate that <1% of p122 is in the CBTF complex (45). In addition, the amount of p122 present in the embryo does not alter until after CBTF activity is detectable in nuclei (5). CBTF is present in the embryo before nuclear translocation occurs, and one might predict that it would gain access to the nucleus as an intact, active complex. This is clearly not the case, and it is possible that CBTF moves into the nucleus either as separate subunits or as an inactive complex, becoming active only at the start of gastrulation. These data strongly suggest that a multistep process is responsible for the translocation of CBTF into the nucleus. The mechanism holding p122 in the cytoplasm before stage 9 is under investigation. p122 has a nuclear localization signal (5), but this has not been tested functionally. It is possible that this nuclear localization signal is inactivated by masking with an inhibitor as for NFκB (3) or by modification (40). One strong possibility is that RNA binding holds p122 in the cytoplasm, as has been suggested for XLPOU60 (20). The movement of p122 into the nucleus occurs as many of the maternal mRNAs to which it binds are degraded. Since the pattern of subcellular movement of p122 closely resembles that of xnf7, a protein whose control has been intensively studied (15, 18, 31, 32, 40, 56), we checked for regions of homology between the two (especially for a cytoplasmic retention domain). None were apparent; thus, the cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation of p122 is most likely regulated by a mechanism separate from that which regulates xnf7. We observed perinuclear staining in the large, yolky cells of stage 6 embryos. While this may be a simple consequence of exclusion from the remainder of the cytoplasm by yolk granules, a similar staining pattern has been observed in the less yolky animal pole cells at stage 8 and for other proteins which undergo translocation into the nucleus: c-myc (65) and Hsp70 (24). For c-myc, this has also been observed in cultured cells where there is no yolk and hence has been proposed to be a stage in the nuclear translocation process (65).

It is clear from the data presented here and elsewhere (5, 70) that p122 is a maternal transcription factor with a dual role. Other vertebrate maternal transcription factors are also known to have second functions in embryos. For example, in Xenopus, the CCAAT factor FRGY2 also has a role in masking mRNA (38), while β-catenin anchors cadherin and forms a transcription factor with XTCF-3 (22). In mice, Oct-3 and Sp1 have both been proposed to have roles in controlling DNA synthesis (54, 71), in addition to transcription. Such dual roles are perhaps no surprise when one considers the limit on the amount of material which can be produced and stored in an egg and the complex developmental process it must control. These dual roles may be a general property of maternal transcription factors in vertebrates. A second characteristic of CBTF which may also be a general property of such factors, at least in Xenopus, is cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation, of which there are now several examples (6, 30, 40, 55, 68). Our data and those relating to c-myc (65) strongly suggest that a multistep process underlies the movement of these proteins into the nucleus. Since CBTF demonstrates both dual functions and also cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation, its further investigation will add to our knowledge of mechanisms common to a number of vertebrate maternal transcription factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Rob Orford and Carl Robinson contributed equally to the work presented here.

We thank Alison Snape and Jim Smith for the cDNA expression library and Brenda Bass and Mike Wormington for reagents, discussions, and allowing us access to data prior to publication. We are also most grateful to Geoff Kneale, Colyn Crane-Robinson, and Sarah Newbury for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (U.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelilah S, Driever W. Pattern formation in janus-mutant zebrafish embryos. Dev Biol. 1997;184:70–84. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almouzni G, Wolffe A P. Constraints on transcriptional activator function contribute to transcriptional quiescence during early Xenopus embryogenesis. EMBO J. 1995;14:1752–1765. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. IκB: a specific inhibitor of the NF-κB transcription factor. Science. 1988;242:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3140380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barberis A, Superti-Furga G, Busslinger M. Mutually exclusive interaction of the CCAAT-binding factor and of a displacement protein with overlapping sequences of a histone gene promoter. Cell. 1987;50:347–359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bass B L, Hurst S R, Singer J D. Binding properties of newly identified Xenopus proteins containing dsRNA-binding motifs. Curr Biol. 1994;4:301–314. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bearer E L. Distribution of Xrel in the early Xenopus embryo: a cytoplasmic and nuclear gradient. Eur J of Cell Biol. 1994;63:255–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertwistle D, Walmsley M E, Read E M, Pizzey J A, Patient R K. GATA factors and the origins of adult and embryonic blood in Xenopus—responses to retinoic acid. Mech Dev. 1996;57:199–214. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer A C, Guille M J, Fear D J, Partington G A, Patient R K. Nuclear translocation of a maternal CCAAT factor at the start of gastrulation activates Xenopus GATA-2 transcription. EMBO J. 1995;14:757–766. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chodosh L A, Olesen J, Hahn S, Baldwin A S, Guarente L, Sharp P A. A yeast and a human CCAAT-binding protein have heterologous subunits that are functionally interchangeable. Cell. 1988;53:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corthesy B, Kao P N. Purification by DNA affinity chromatography of 2 polypeptides that contact the NF-AT DNA-binding site in the interleukin-2 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20682–20690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn A, Bollekens J, Staub A, Benoist C, Mathis D. A multiplicity of CCAAT box binding proteins. Cell. 1987;50:863–872. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorn A, Durand B, Marfing C, Le Meur M, Benoist C, Mathis D. Conserved major histocompatibility complex class II boxes—X and Y—are transcriptional control elements and specifically bind nuclear proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6249–6253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreyer C, Wang Y H, Wedlich D, Hansen P. Oocyte nuclear proteins in the development of Xenopus. In: McClaren A, Wylie C, editors. Current problems in germ cell differentiation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1983. pp. 322–352. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzierzak E, Medvinsky A. Mouse embryonic hematopoiesis. Trends Genet. 1995;11:359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ElHodiri H M, Che S L, NelmanGonzalez M, Kuang J, Etkin L D. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and cyclin B/Cdc2 phosphorylate Xenopus nuclear factor 7 (xnf7) in extracts from mature oocytes—implications for regulation of xnf7 subcellular localization. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20463–20470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans T, Reitan M, Felsenfeld G. An erythroid-specific DNA-binding factor recognizes a regulatory sequence common to all chicken globin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5976–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleenor D E, Langdon S D, Decastro C M, Kaufman R E. Comparison of human and Xenopus GATA-2 promoters. Gene. 1996;179:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong S-G, Reddy B A, Etkin L D. Two forms of Xenopus nuclear factor 7 have overlapping spatial but different temporal patterns of expression during development. Mech Dev. 1995;52:305–318. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gove C, Walmsley M, Nijjar S, Bertwistle D, Guille M, Partington G, Bomford A, Patient R. Over-expression of GATA-6 in Xenopus embryos blocks differentiation of heart precursors. EMBO J. 1997;16:355–368. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guttridge K L, Smith L D. Xenopus interspersed RNA families, Ocr and XR, bind DNA-binding proteins. Zygote. 1995;3:111–122. doi: 10.1017/s0967199400002483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harland R M. In situ hybridisation: an improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:685–695. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heasman J. Patterning the Xenopus blastula. Development. 1997;124:4179–4191. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heldin C-H, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-b signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–468. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herberts C, Moreau N, Angelier N. Immunolocalization of Hsp 70-related proteins constitutively expressed during Xenopus laevis oogenesis and development. Int J Dev Biol. 1993;37:397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang Y M, Evans T. The Xenopus GATA-4/5/6 genes are associated with cardiac specification and can regulate cardiac-specific transcription during embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1996;174:258–270. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao P N, Chen L, Brock G, Ng J, Kenny J, Smith A J, Corthesy B. NFAT sequence-specific DNA-binding protein is a novel heterodimer of 45-Kda and 90-Kda subunits. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20691–20699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley C, Yee K, Harland R, Zon L I. Ventral expression of GATA-1 and GATA-2 in the Xenopus embryo defines induction of hematopoietic mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1994;165:193–205. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koyano S, Ito M, Takamatsu N, Takiguchi S, Shiba T. The Xenopus Sox3 gene expressed in oocytes of early stages. Gene. 1997;188:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laverriere A C, MacNiell C, Mueller C, Poelmann R E, Burch J B E, Evans T. GATA-4/5/6: a subfamily of three transcription factors transcribed in the developing heart and gut. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23177–23184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemaitre J M, Bocquet S, Buckle R, Mechali M. Selective and rapid nuclear translocation of a C-Myc-containing complex after fertilization of Xenopus laevis eggs. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5054–5062. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Shou W, Kloc M, Reddy B A, Etkin L D. Cytoplasmic retention of Xenopus nuclear factor-7 before the mid-blastula transition uses a unique anchoring mechanism involving a retention domain and several phosphorylation sites. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:7–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X X, Shou W, Kloc M, Reddy B A, Etkin L D. The association of Xenopus nuclear factor 7 with subcellular structures is dependent upon phosphorylation and specific domains. Exp Cell Res. 1994;213:473–481. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lum L S Y, Sultzman L A, Kaufman R J, Linzer D I H, Wu B J. A cloned human CCAAT-box-binding factor stimulates transcription from the human hsp70 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6709–6717. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeno M, Mead P E, Kelley C, Xu R H, Kung H F, Suzuki A, Ueno N, Zon L I. The role of BMP-4 and GATA-2 in the induction and differentiation of hematopoietic mesoderm in Xenopus laevis. Blood. 1996;88:1965–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin D I K, Orkin S H. Transcriptional activation and DNA binding by the erythroid factor GF-1/NF-E1/Eryf 1. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1886–1898. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massague J, Hata A, Liu F. TGF-beta signalling through the Smad pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:187–192. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massangue J. TGF-b signalling: receptors, transducers and Mad proteins. Cell. 1996;85:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto K, Meric F, Wolffe A P. Translational repression dependent on the interaction of the Xenopus Y-box protein FRGY2 with messenger-RNA—role of the cold shock domain, tail domain, and selective RNA sequence recognition. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22706–22712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng A M, Tang H, Ong B A, Farrell M J, Lin S. Promoter analysis in living zebrafish embryos identifies a cis-acting motif required for neuronal expression of GATA-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6267–6272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller M, Reddy B A, Kloc M, Li X X, Dreyer C, Etkin L D. The nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution of the Xenopus nuclear factor, xnf7, coincides with its state of phosphorylation during early development. Development. 1991;113:569–575. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minegishi N, Ohta J, Suwabe N, Nakaushi H, Ishihara H, Hayashi N, Yamamoto M. Alternative promoters regulate transcription of the mouse GATA-2 gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3625–3634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nerlov C, Ziff E B. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-a amino acid motifs with dual TBP and TFIIB binding ability co-operate to activate transcription in both yeast and mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:4318–4328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nieuwkoop P D, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North Holland; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nusse R. A versatile transcriptional effector of wingless signalling. Cell. 1997;89:321–323. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orford, R. L., C. Robinson, and M. J. Guille. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 46.Orford, R. L., G. G. Kneale, and M. J. Guille. Unpublished data.

- 47.Orkin S H. Regulation of globin gene expression in erythroid cells. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ovsenek N, Karn H A, Heikilla J J. Analysis of CCAAT box transcription factor binding activity during early Xenopus laevis embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1991;145:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90130-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Partington G A, Bertwistle D, Nicolas R H, Kee W J, Pizzey J A, Patient R K. GATA-2 is a maternal transcription factor present in Xenopus oocytes as a nuclear complex which is maintained throughout early development. Dev Biol. 1997;181:144–155. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patterton D, Wolffe A P. Developmental roles for chromatin and chromosomal structure. Dev Biol. 1996;173:2–13. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piccolo S, Sasai Y, Lu B, DeRobertis E M. Dorsoventral patterning in Xenopus—inhibition of ventral signals by direct binding of chordin to BMP-4. Cell. 1996;86:589–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prioleau M-N, Huet J, Sentenac A, Mechali M. Competition between chromatin and transcription complex assembly regulates gene expression during early development. Cell. 1994;77:439–449. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Read, E. M., A. R. F. Rodaway, B. Neave, N. Brandon, N. Holder, R. K. Patient, and M. E. Walmsley. GATA factor expression reveals early regionalisation within the non-neural ectoderm of Xenopus and zebrafish embryos: A/P patterning by FGF. Submitted for publication.

- 54.Rosner M H, Desanto R J, Arnheiter H, Staudt L M. Oct-3 is a maternal factor required for the 1st mouse embryonic division. Cell. 1991;64:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90265-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rupp R A W, Snider L, Weintraub H. Xenopus embryos regulate the nuclear localization of XMyoD. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1311–1323. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shou W, Li X, Wu C F, Cao T, Kuang J, Che S, Etkin L D. Finely tuned regulation of cytoplasmic retention of Xenopus nuclear factor 7 by phosphorylation of individual threonine residues. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:990–997. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon M C. Gotta have GATA. Nat Genet. 1995;11:9–11. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith L D, Xu W, Varnold R L. Oogenesis and oocyte isolation. In: Kay B K, Peng H B, editors. Xenopus laevis: practical uses in cell and molecular biology. Vol. 36. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith W C, Knecht A K, Wu M, Harland R M. Secreted noggin protein mimics the Spemann organiser in dorsalising Xenopus mesoderm. Nature. 1993;361:547–549. doi: 10.1038/361547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sykes, T. G., A. R. F. Rodaway, M. E. Walmsley, and R. K. Patient. A dominant interfering GATA factor inhibits wnt-8 expression and causes secondary axis formation in Xenopus. Submitted for publication.

- 61.Tsai F Y, Keller G, Kuo F C, Weiss M, Chen J, Rosenblatt M, Alt F W, Orkin S H. An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature. 1994;371:221–226. doi: 10.1038/371221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsai F Y, Orkin S H. Transcription factor GATA-2 is required for proliferation/survival of early hematopoietic cells and mast cell formation, but not for erythroid and myeloid terminal differentiation. Blood. 1997;89:3636–3643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Veenstra G J C, Beumer T J, Petersonmaduro J, Stegeman B I, Karg H A, Vandervliet P J, Destree O H J. Dynamic and differential Oct-1 expression during early Xenopus embryogenesis—persistence of Oct-1 protein following down-regulation of the RNA. Mech Dev. 1995;50:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00328-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vinson C, LaMarco K, Johnson P, Landschultz W, McKnight S. In situ detection of sequence specific DNA binding activity specified by a recombinant bacteriophage. Genes Dev. 1988;2:801–806. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vriz S, Lemaitre J-M, Leibovici M, Thierry N, Méchali M. Comparative analysis of the intracellular localization of c-Myc, c-Fos, and replicative proteins during cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3548–3555. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walmsley M E, Guille M J, Bertwistle D, Smith J C, Pizzey J A, Patient R K. Negative control of Xenopus GATA-2 by activin and noggin with eventual expression in precursors of the ventral blood islands. Development. 1994;120:2519–2529. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whiteside S T, Goodbourn S. Signal transduction and nuclear targeting: regulation of transcription factor activity by subcellular localisation. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:949–955. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.4.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Whitfield T T, Heasman J, Wylie C C. Early embryonic expression of XLPOU-60, a Xenopus POU-domain protein. Dev Biol. 1995;169:759–769. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolffe A P, Tafuri S, Ranjan M, Samilari M. The Y-box factors: a family of nucleic acid binding proteins conserved from Escherichia coli to man. New Biol. 1992;4:290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wormington, M. 1997. Personal communication.

- 71.Worrad D M, Ram P T, Schultz R M. Regulation of gene expression in the mouse oocyte and early preimplantation embryo—developmental changes in Sp1 and TATA box-binding protein, TBP. Development. 1994;120:2347–2357. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wyllie A H, Laskey R A, Finch J, Gurdon J B. Selective DNA conservation and chromatin assembly after injection of SV40 DNA into Xenopus oocytes. Dev Biol. 1978;64:178–188. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamamoto M, Ko L J, Leonard M W, Beug H, Orkin S H, Engel D. Activity and tissue-specific expression of the transcription factor NF-E1 multigene family. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1650–1662. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoon J-B, Murphy S, Bai L, Wang Z, Roeder R G. Proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor (PTF) is a multisubunit complex required for transcription of both RNA polymerase II- and RNA polymerase III-dependent small nuclear RNA genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2019–2027. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang C H, Evans T. BMP-like signals are required after the midblastula transition for blood-cell development. Dev Genet. 1996;18:267–278. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:3<267::AID-DVG7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zimmerman L B, Jesus-Escobar J M D, Harland R M. The Spemann organiser signal noggin binds and inactivates bone morphogenic protein 4. Cell. 1996;86:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zon L I, Mather C, Burgess S, Bolce M, Harland R M, Orkin S H. Expression of GATA binding proteins during embryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10642–10646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]